Over the past four chapters, we have considered the four main figures in the phenomenological tradition. Although, as we have seen, the phenomenological tradition is hardly monolithic, replete as it is with intramural debates and in some cases wholesale changes in orientation (consider the divide between Husserl's and Heidegger's respective conceptions of phenomenology), there is nonetheless among these figures a shared sense of there being a distinctive philosophical discipline worthy of the name "phenomenology", and so a shared sense that phenomenology is both possible and, indeed, philosophically indispensable. Despite many differences both at the programmatic level and at the level of detail, all four figures - Husserl, Heidegger, Sartre and Merleau-Ponty - agree that phenomenology is not only worth doing, but that it aspires to be the method for philosophy.

In presenting the views of these four figures, I have taken something of a "used-car salesman" approach, highlighting the strengths of each position and downplaying the weaknesses, except where outright incompatibilities among the positions prevented my doing so. I have thus served more or less as an advocate for each position, all the while realizing that one could not embrace all four simultaneously. Although one must pick and choose among these positions in phenomenology, there remains the option of opting out of phenomenology altogether, and not just out of personal interest and inclination, but because of more principled philosophical considerations. That is, perhaps it is the case that the shared sensibility among our four figures that phenomenology is both possible and valuable is itself open to dispute. Perhaps the very idea of phenomenology is somehow limited, intrinsically flawed or ill-conceived, and so rather than choosing among the viewpoints canvassed over the last four chapters, we should instead remain more aloof, withholding our wholehearted acceptance or even rejecting them in their entirety.

In this final chapter, we shall examine phenomenology from a more critical perspective, exploring a number of views that try, variously, to expose the limits to phenomenological investigation or, more radically, reveal fatal underlying flaws. We shall consider three such critical perspectives - those of Emmanuel Levinas, Jacques Derrida and Daniel Dennett - that are connected by a number of intransitive similarities (Levinas's position is similar in some respects to Derrida's, and Derrida's is similar in some respects to Dennett's, but one would be hard-pressed to find much of any similarity between Levinas and Dennett). Of the three, Levinas and Derrida are most closely affiliated with the phenomenological tradition. The lines of affiliation are in each case multiple, encompassing cultural, chronological and, most importantly, philosophical affiliations. Levinas was born in Lithuania, but studied and worked in France and wrote in French. Derrida was born in Algeria, but later studied and taught in France as well. Levinas was born a year after Sartre, and two years before Merleau-Ponty. Derrida is of more recent vintage, but studied philosophy at a time when some of the major works of phenomenology were relatively recent. Levinas was a dedicated student of Husserl's philosophy, providing early translations of his work into French and writing an early book-length work and numerous essays on his philosophy, and he was also a close reader of Heidegger. Derrida's early work in philosophy was likewise steeped in Husserl's phenomenology, although always from a more critical perspective, and he wrestled with Heidegger's philosophy throughout his philosophical career (indeed, Derrida's strategy of "deconstruction" was influenced considerably by Heidegger's task, in Being and Time and elsewhere, of "destroying the history of ontology" - see e.g. BT: §6).

Dennett, by contrast, occupies a position far more external to the phenomenological tradition. American, trained in England, and possessed of philosophical sensibilities steeped in the kind of science-centered naturalism to which the phenomenological tradition is opposed, Dennett nonetheless sees his own philosophy of mind as emerging in part out of a critical engagement with phenomenology, especially the phenomenology of Husserl (at one point, Dennett modestly describes himself as "no Husserl scholar but an amateur of long standing" (BS: 184)). Moreover, and perhaps surprisingly, Dennetts critical engagement with phenomenology overlaps with Derrick's, and both use their criticisms as a basis for reconceiving the very idea of consciousness in ways very much at odds with how Husserl (and also Sartre) conceives of it. (Levinas's criticisms, by contrast, are far more tempered: he is concerned not so much with overthrowing phenomenology, as showing where phenomenological method comes up short. These shortcomings are far from trivial, however, so Levinas is certainly offering something more than merely polite disagreement.)

The bulk of this chapter will be devoted to laying out and assessing these critical perspectives on the phenomenological tradition, but in the final part I shall briefly address the question of phenomenology's continued significance for philosophy and suggest that we would do well to view the phenomenological tradition as far more than a museum piece. In this book, at least, phenomenology gets the last word.

In the preceding chapters we paid little heed to a theme that runs through the entirety of phenomenology (and really a great deal of philosophy ever since Descartes). Although we have considered many modes and categories of manifestation - spatiotemporal objects (Husserl), equipment and world (Heidegger), the ego or self (Sartre) and the body (Merleau-Ponty) - we have not considered in any detail the distinctive ways in which others, that is, other subjects of experience, show themselves in experience. Two questions immediately present themselves:

The more pointed version of the question is prompted by the following kind of worry. I have direct or immediate "access" via reflection to my own experience or consciousness, but in what way, and to what extent, can I experience the experience or consciousness of another subject of experience? And if, the worry continues, the consciousness of another subject is not available to me, that is, is not something that I can directly experience, then in what sense can I be said to experience the other as a conscious being at all?

These questions may be familiar from discussions outside the context of phenomenology, as they are the sorts of questions one generally rehearses in raising the sceptical "problem of other minds". The problem in its general form concerns the possibility of ascertaining or knowing that there are other minds besides my own. The existence of my own mind is vouchsafed by the direct and immediate availability of my own experience, but nothing like that is forthcoming with respect to any other minds. Lacking this kind of direct availability, I can never establish or know that there are indeed such other minds. The problem thus treats my relation to "the other" as fundamentally epistemological - as a problem about "access" or knowledge - and very often the worry is raised in order to show that it cannot be assuaged.

In many ways, the phenomenological tradition as a whole is very much alive to the problem of other minds. This is not to say that every figure within the tradition treats the problem as a straightforward problem in need of a solution (Husserl comes closest to holding this view), but all of the figures we have considered in the preceding chapters see it as a problem to be addressed, even if the form of address involves showing why the problem, at least in its epistemological form, is ultimately a bogus one. One way of measuring the importance of Levinas is to see him as attempting to sidestep this problem altogether. The relation to the other is not epistemological, but ethical, and the whole attempt to accommodate or account for the other within the confines of my experience already constitutes a breach of this fundamental ethical relation. The other is precisely that which cannot be the object of my experience in the sense of being completely manifest within it, and so cannot be construed as a phenomenon at all. As something that does not manifest itself in the field of my experience, there cannot be a phenomenology of the other or of otherness: in the encounter with the other, phenomenology has thus reached an impasse.

To work our way further into Levinas, and so understand the nature of these criticisms of phenomenology, we might best begin by considering the title of his most important work, Totality and Infinity. The first term in this pair, "totality", is Levinas's name for what he sees as the underlying telos of the Western intellectual tradition, namely, the goal of comprehending everything there is within one, all-embracing framework, theory or system. Consider the justly famous opening line of Aristotle's Metaphysics: "All men by nature desire to know" (Metaphysics I, 1). In Levinas's terms, Aristotle is here naming this desire for totality, which in Aristotle is cashed out as the goal of ordering everything there is so as to be derivable from, and so explained in terms of, a hierarchically organized set of principles. Western philosophy, along with the natural sciences that emerged from it, has throughout its history displayed this longing for totality, for a "grand theory of everything". Levinas refers to this quest for totality as an endeavour to assimilate everything to the same: by rendering everything intelligible according to one comprehensive system of principles, everything is thereby rendered categorically homogenous (there is certainly room for the idea of differentiation, and so heterogeneous categories, but this is all diversity within unity).

The linkage between totality and assimilation indicates a certain kind of orientation on the part of the subject towards the world. Levinas dubs this orientation "enjoyment". Eating is one basic form of enjoyment where the notion of assimilation is particularly vivid. The food that I eat is taken in and digested, and thereby incorporated into my body and no matter how many different kinds of food I eat, they are all inevitably chewed and mixed into one amalgam in the interior of my one body. The assimilative act of eating is not the only source of enjoyment; perceptual experience also affords such pleasures. Consider the continuation of Aristotle's opening claim: that all men desire to know is indicated by "the delight we take in our senses; for even apart from their usefulness they are loved for themselves; and above all others the sense of sight" (Metaphysics I, 1). Although vision serves many practical purposes, very often we simply enjoy looking at things, taking them in with our eyes, even when we have no further purpose beyond the pleasure of gazing. Note the phrase "taking them in" in the previous sentence, which indicates that seeing, and perceiving more generally, is also a kind of assimilation, although in a less straightforward way than eating. In the act of perception, I apprehend (a synonym for "take") the object; I bring it within the field of my experience, and so in that sense make it mine, or even a part of me. When I perceive, the thing I perceive is open to view, available to me, and so under my dominion: "Inasmuch as the access to beings concerns vision, it dominates those beings, exercises a power over them. A thing is given, offers itself to me. In gaining access to it I maintain myself within the same" (TI: 194). Vision is commonly referred to as a "power", and to have things in view is already to exercise a kind of control over them. Looking at something is often the first step in investigating it, getting to know it and figuring out what it is and how it works. This kind of control is itself also pleasurable.

Although Levinas sees these themes of totality and assimilation running through the entirety of Western philosophy, the phenomenological tradition is his more immediate target. Indeed, one of Levinas's principal claims is that these themes are no less present in phenomenology than elsewhere in Western philosophical tradition, despite phenomenology's self-understanding as an enlightened response to that larger tradition (consider, for example, Heidegger's critique of philosophy's preoccupation with substance and actuality, or Merleau-Ponty's rejection of both intellectualism and empiricism). The very idea of phenomenology, of the phenomenon as what "shows itself" or as given, betrays the continued presence of these themes. Phenomenology's defining demand that things be made manifest is both totalizing (phenomenology treats everything as a phenomenon to be described and categorized) and assimilating (by treating everything as a phenomenon, as something manifest, phenomenology both treats everything as ultimately the same and pulls everything within the dominating gaze of the subject). Husserl's conception of transcendental consciousness as the all-encompassing field of intelligibility in which intentional objects are constituted provides a vivid example of these totalizing and assimilative tendencies of phenomenology, but Heidegger too is not immune to Levinas's criticisms, despite Heidegger's own criticisms of Husserl. In Being and Time, Heidegger characterizes his project as "fundamental ontology", and so as dedicated to answering the question of the meaning of being in general. Heidegger's preoccupation with being manifests a continued striving for totality, and his equating of being with the notion of a phenomenon as "what shows itself" is no less assimilating than Husserl's notion of constitution.

But what do these general criticisms of phenomenology, as no less guilty of certain very general aspirations and ambitions, have to do with a proper conception of the other, or the very idea of otherness? How do these aspirations and ambitions entail any kind of neglect or oversight of the fundamentally ethical character of my relation to the other? Let us begin to answer these questions by looking in more detail at some aspects of phenomenology's approach to the question of the other.

The problem of others is especially acute in Husserl's phenomenology, given the phenomenological reduction and the absolute character of the first-person singular point of view. Although Husserl wants to allay the worry that "solipsism", the view that I am the only genuine subject of experience or sentient being, constitutes a permanent condition, at the same time he is clear that the legitimate starting-point for phenomenology is a solipsistic one. Where Husserl's phenomenology begins is with the reduction to the stream of experience of the transcendental ego, the self, the subject or the "I" of the cogito. From this starting-point, the stream of conscious experience, one proceeds outwards, so to speak, via the process of constitution: the constitution of any intentional object, the constitution of actual objects and so on. Given this sort of starting-point, however, it is not difficult to see how there comes to be a problem of other egos, since the appeal to constitution seems unsatisfactory. That is, one cannot be satisfied simply with explaining the constitution of the other as part of my immanent stream of experience, since the very idea of an other involves its being outside my stream of experience, and indeed a possessor of its own stream of experience. The constitution of the other would thus seem to require constituting the other's stream of experience, but doing so would make that stream a part of mine, which undermines the idea that I have succeeded in constituting, and so experiencing, a genuine other, another subject of experience. For Husserl, "the possibility of the being for me of others" is "a very puzzling possibility" (CM: §41), and so a problem very much in need of a solution. For Levinas, by contrast, the problem lies with this very conception of the problem, namely treating the problem of the other as a constitutional one. To constitute the other, in Husserl's sense of constitution, is thereby to assimilate the other to, or within, the field of one's own experience, thereby depriving the other of its very otherness.

We saw in Chapter 2 that Heidegger, in keeping with his rejection of the phenomenological reduction, rejects the problem of other minds as a pseudo-problem. The primacy of Dasein, as being-in-the-world, precludes the kind of solipsistic perspective found in Husserl. For Heidegger, the "being for me of others" is not a "puzzling possibility", as it was for Husserl, since I and others are from the start together, out there in the world. Heidegger thus rejects the kind of explanatory project Husserl thinks phenomenology must confront. Instead, others "are encountered from out of the world, in which concernfully circumspective Dasein essentially dwells", and so Heidegger rejects any "theoretically concocted 'explanations' of the being-present-at-hand of others" (BT: §26). We must, Heidegger insists, "hold fast to the phenomenal facts of the case which we have pointed out, namely, that others are encountered environmentally" (ibid.).

For Heidegger, self and other are, we might say, co-manifest, and the other shows himself or herself to be an other who is the same as me:

By others we do not mean everyone else but me - those over against whom the "I" stands out. They are rather those from whom, for the most part, one does not distinguish oneself those among whom one is too. This being-there-too with them does not have the ontological character of a being-present-athand-along-"with" them within a world. This "with" is something of the character of Dasein; the "too" means a sameness of being as circumspectively concernful being-in-the-world.

(BT: §26)

The lack of any sharp distinction in everydayness between self and other, such that I and others are marked by "a sameness of being", undermines the intelligibility of the problem of other minds. The question "How can I know that there are other subjects of experience?" fails to raise any epistemological alarms, when the way of being of the "I" in the question is revealed to be being-in-the-world. Dasein, as being-in-the-world, "always already" has an understanding of others (what Heidegger calls "being-with"), and so there is no general worry about how such understanding or knowledge is possible (there may, of course, be worries on particular occasions as to what someone is thinking or feeling). Although Heidegger is dismissive of the epistemological problem of other minds, condemning it as a pseudo-problem rather than one to be solved, his stance on the question of others is one that Levinas nonetheless finds problematic. The problem is signalled in the final sentence of the passage quoted above, where Heidegger essentially assimilates the other as being or having the same way of being as the "I". For Heidegger, others are not truly encountered as others, and for Levinas, this means that the otherness of the other is effaced.

Sartre's phenomenology of the other in Being and Nothingness begins with the idea that if we start from the perspective of our own, individual experience, there is naturally a kind of privileging of ourselves and that experience. Each of us, with respect to our own experience, constitutes, in Husserl's words, a "zero-point of orientation", and so the world that we experience, its layout and patterning, is for each of us organized around ourselves. When I am alone, the world I experience is my world, in the sense that everything manifests itself only to me and only in relation to me: things are near and far, over here or over there, in front or behind, solely in relation to the position I occupy. My perspective on the world is the only perspective there is, again provided that I am alone. For Sartre, the first effect of the appearance of the other is to disrupt, indeed shatter, this complacent sense of exclusive ownership and privilege. Hie appearance of the other marks the appearance of an object in my experience with its own experience, and so it marks the appearance of someone else around whom the world is perceptually and perspectivally organized: "The Other is first the permanent flight of things towards a goal which I apprehend as an object at a certain distance from me but which escapes me inasmuch as it unfolds about itself its own distances (BN: 343). When the other comes on the scene, the world is no longer exclusively mine. Instead, there is "a regrouping of all the objects which people my universe" (ibid.) around this new kind of object.

This regrouping "escapes me" in so far as I am unable to inhabit the perspective occupied by the other. Even if I were to move to the precise location of the other and move him out of the way, thereby orienting my body precisely as his was prior to my intrusion, I would still not be having his experience, and indeed, his experience would continue from whatever new location he took up, thereby effecting yet another regrouping to which I am not privy. As Sartre puts it, objects and their qualities turn "toward the Other a face which escapes me. I apprehend the relations of [objects and their qualities] to the Other as an objective relation, but I cannot apprehend [them] as" (ibid.) they appear to him. The appearance of the other is thus the appearance of an object that "has stolen the world from me" (ibid.).

These disruptions caused by the appearance of the other in my experiential field are only the beginning, since with these considerations concerning perspective and orientation, "the Other is still an object for me" (ibid.). The other's subjectivity is most palpable when his experience is directed not towards objects that I too am experiencing, but when his experience is directed towards me, so that "my fundamental connection with the Other-as-subject must be able to be referred back to my permanent possibility of being seen by the Other" (BN: 344). The experience of being seen by the other is to be subject to what Sartre calls "the look". When I experience the other as something capable of experiencing me, when, that is, I find myself subjected to the look, I am at that moment transformed from a subject into an object. Recall Sartre's characterization of first-degree consciousness in The Transcendence of the Ego: the field of first-degree consciousness is unowned, and so is nothing but pure subjectivity. When I am absorbed in my own experience, there is no me that appears in that experience. The appearance of the other disrupts all of this, suddenly making me aware of myself and so objectifying me. I now feel myself to be an object to be perceived, who is caught up in the perspective opened up by the other's experience. For Sartre, the look is primarily threatening. Hie other is experienced primarily as a source of shame, self-consciousness (in the ordinary sense) and vulnerability: "What I apprehend immediately when I hear the branches crackling behind me is not that there is someone there; it is that I am vulnerable, that I have a body which can be hurt, that I occupy a place in which I am without defense - in short, that I am seen" (BN: 347).

Sartre's phenomenology of the other thus does not commit what is for Levinas the sin of assimilating the other to the realm of the same, as Heidegger does. That for Sartre the other occupies a perspective or has a point of view on the world that is in principle unavailable to me is for Levinas a step in the right direction in terms of properly characterizing the relation between self and other. For both Sartre and Levinas, the appearance of the other constitutes a radical disruption of the homogeneity of my experience. Even the appearance of the other-as-object in Sartre marks the appearance of something that resists complete assimilation, as the qualities of the world as they appear to the other "escape me". At the same time, Sartres overall conception of the self-other relation is still underwritten by the drive for totality and assimilation: the objectifying power of "the look" seeks in each case to deprive the other of his or her subjectivity, thereby making the other just one more thing in my perceptual field. The extent to which Sartre's account of the self-other relation is permeated with notions of hostility, antagonism and threat indicates a failure on Sartre's part to recognize anything beyond this drive towards objectification, anything, that is, beyond the goal of totality. Lacking in Sartre is any sense in which the appearance of the other can be seen as welcoming, as informed by hospitality rather than vulnerability, and so as involving an unqualified acknowledgment of the other's unsurveyable subjectivity. Lacking in Sartre and the rest of the phenomenological tradition is a proper appreciation of what Levinas calls "the face".

The appearance of the other is the appearance of something that exceeds appearance, that cannot, in other words, be assimilated by me into the same:

The face is present in its refusal to be contained. In this sense it cannot be comprehended, that is, encompassed. It is neither seen nor touched - for in visual or tactile sensation the identity of the I envelops the alterity of the object, which becomes precisely a content.

(TI: 194)

Notice especially the conclusion of this passage. Perception, as a fundamental form of intentionality, always involves intentional content. The object I perceive is the content of my perceptual experience, and so comprehended by that experience. The containment need not be literal, of course. When I look at my coffee cup, the cup is the content of my visual experience, but the cup itself is out there, on my desk. Nonetheless, in offering itself to my gaze, the cup is thereby assimilated by me, incorporated into my visual field.

The disanalogy between objects and the face in Levinass sense is difficult to characterize adequately. Two worries immediately present themselves, both of which concern the alleged distance between the face and ordinary objects of perception, such as my coffee cup. First, it is unclear what Levinas means by saying that the face can be "neither seen nor touched", since, if we consider real human faces, this just sounds obviously false. The other, including the other's face, is there to be seen, just as the coffee cup he holds is visually present to me. (This remark, on its own, hardly constitutes an objection, since "face" for Levinas need not refer to a literal face; however, his choice of terminology would suggest that what he means by "face" is somehow bound up with, or most centrally attested to in, our face-to-face encounters with one another.) We need to be careful, however, in terms of how we understand the claim that the cup and the other are equally "there to be seen". Hie range of possibilities is markedly different in the case of the cup. The cup does not, and indeed cannot, refuse or resist my gaze, nor can it turn away from me, hide from me, or in any way prevent my continued inspection. The person holding the cup may of course hide the cup from me, and so in that way the cup resists my gaze, but that is certainly not the cup's doing. The other person is the source of this refusal or resistance, and so what my gaze really fails to contain is him or her, not the cup. In always offering at least the possibility of such resistance, the other always exceeds my perceptual capacities. But this brings us to the second worry. After all, the cup, as a spatiotemporal object, is only presented to me via adumbrations, and so any presentation of the cup always involves the intimation of unseen or hidden sides. Indeed, since the cup is, perceptually speaking, an infinite system of adumbrative presentations, it would seem that my perceptual experience could never fully contain or comprehend the cup. Thus, the disanalogy between the face and ordinary objects is still found wanting.

Although it is indeed the case that the perception of ordinary spatiotemporal objects involves the notion of hidden sides, such that no one presentation (or even many) will fully contain or comprehend the object, there are nonetheless several ways in which the disanalogy between such objects and the face might be sustained. We may begin by noting that in the case of spatiotemporal objects the hidden sides are only contingently hidden from me. For example, if I am looking at the front of my coffee cup, I cannot at the same time see the back of it or the bottom, but I can move myself or the cup whenever I wish so as to reveal those currently hidden aspects. Even if we allow that the presentation of the cup involves an infinite system of adumbrations, so that I, as a finite subject, could never experience all of them, it is still the case that no particular side of the cup is in principle hidden from me; nor is it the case that the cup may in any sense keep a particular side hidden from me. The hidden sides in the case of the face, however, can be hidden in just these two ways. To start with the second, if we consider the power of resistance or refusal, the other may always refuse to reveal a hidden side. I have to allow, in my encounter with another person, that there may be things that I will never know about that person, things that the person may choose to keep secret. Moreover, if we recall Sartre's talk about the other as occupying a point of view that "escapes me", we can see that the others sides are hidden to a further extent beyond what he or she chooses to reveal. I can never occupy the point of view of the other, take his or place, in the sense of thereby having the others experience. The others subjectivity is in this way non-contingently, that is, in principle, hidden from me.

There is still another way in which to sustain the disanalogy, if we think about the relations among the "hidden sides" in the two cases. When I look at the front of my coffee cup, the currently hidden sides are hidden in such a way that they are predictably connected with what is present to me now I know when looking at the front of the cup what will happen when I turn the cup or lift it up, and so what I am seeing now and the hidden sides do indeed make up a series or system. As long as no one has substituted a trick cup while I was out of my study, there is nothing surprising in my visual experience of the cup. The encounter with the other, by contrast, is marked by a lack of any such predictability: even when I feel that I know what someone is going to do or say, I may nonetheless still be surprised by how things develop, by what someone actually says or does. The other opposes me not so much with a "force of resistance, but the very unforseeableness of his reaction" (TI: 199). There are, of course, such possibilities for surprise in the case of perceptual experience when we perceive things that are unfamiliar or unusual, but even here, such spectacles hold out the promise of full predictability and so in principle the elimination of any element of surprise. The possibility of surprise in the case of the other is ineliminable.

I have thus far emphasized the notions of resistance and refusal in characterizing the difference between the face and, for example, ordinary spatiotemporal objects, but there is a more positive, happier dimension of this difference as well. Consider the following passage from Levinas's essay "Is Ontology Fundamental?":

A human being is the sole being which I am unable to encounter without expressing this very encounter to him. It is precisely in this that the encounter distinguishes itself from knowledge. In every attitude in regard to the human there is a greeting - if only in the refusal of greeting.

(BPW: 7)

Here Levinas is characterizing the way in which the other, another person, engages me in a way that objects do not. Although I may find particular objects interesting, even beautiful, such that I want to look at them further, keep them nearby, and learn more about them, none of those objects are in any way affected by, or responsive to, that interest: it makes no difference to my coffee cup whether I use it or not, clean it lovingly or leave it unwashed, leave it for days on my desk or in the back of the cupboard, or even smash it to pieces. Whatever form my encounter with the cup takes is not something that I can express to the cup, whereas in the case of another human being, I cannot but express my encounter with him. Whenever I encounter another human being, whatever I do "means something", in the sense that what I say and do can be noticed, ignored, answered, taken up, acknowledged, interpreted, understood, misunderstood and so on. In other words, my encounter with another human being is an occasion for speech. Although I may, in my lonelier moments, talk to the many things around me, another human being is distinguished by his ability to talk back. My encounter with the other is thus marked by the possibility of conversation, indeed the inevitability, since even our failing to acknowledge or engage one another is a way of conversing; a "refusal of greeting" is, for all that, a kind of greeting.

The other remains infinitely transcendent, infinitely foreign, but this "is not to be described negatively" (TI: 194): The negative description is one that emphasizes the lack of comprehension, the failure of predictability, and so on, but "better than comprehension, discourse relates with what remains essentially transcendent" (TI: 195). Again, the other is the one to whom I may speak, and who speaks to me, and "speech proceeds from absolute difference" (TI: 194). This last claim may sound especially jarring, since it would seem, anyway, that speaking involves a common language, and so a shared understanding of what is being said. As Merleau-Ponty puts it, "In the experience of dialogue, there is constituted between the other person and myself a common ground", such that in speaking we are "collaborators for each other in consummate reciprocity" (PP: 354). I would not go so far as to say that Levinas wants to deny these aspects and dimensions of dialogue or conversation, but when he says that "speech proceeds from absolute difference", he is pointing to something all of this talk of commonality, collaboration and reciprocity is apt to cover over: in conversing, there is an "absolute difference" with respect to the location of the speakers. What constitutes individuals as speakers, as participants in a conversation, is precisely their separateness. Without that separateness, speech as conversation collapses. A conversation is not a recitation: the rote production and exchange of a set of sentences. If I already know or can predict everything you will say, because what you say is the standard or conventional thing to say, then you fail to occupy a position fully separated from me; your words may be yours in the causal sense of emanating from your body, but their conventionality renders them anonymous. To be conversation, there must again be an element of the unpredictable, the unforeseeable, such that I cannot, at any point, fully sum up my interlocutor.

Any such attempt at summarization forecloses the possibility of conversation, and indeed, marks the ethical violation of the other:

In discourse the divergence that inevitably opens up between the Other as my theme and the Other as my interlocutor, emancipated from the theme that seemed for a moment to hold him, forthwith contests the meaning I ascribe to my interlocutor. The formal structure of language thereby announces the ethical inviolability of the Other and, without any odor of the "numinous," his "holiness".

(TI: 195)

"The ethical relationship", Levinas claims, "subtends discourse" (ibid.), which means that speaking to and with the other, as involving the other's "absolute difference", at the same time registers the other's inviolability. By acknowledging the other's separateness, I thereby acknowledge as well my ethical responsibility towards the other, in particular my responsibility not to transgress or violate that separateness. Levinas refers to this inviolability of the other as the "infinity of his transcendence". He explains: "This infinity, stronger than murder, already resists us in his face, is his face, is the primordial expression, is the first word: 'you shall not commit murder'" (TI: 199).

"The epiphany of the face is ethical" (TI: 199). It is "ethical" as opposed to ontological: "Preexisting the disclosure of being in general taken as basis of knowledge and as meaning of being is the relation with the existent that expresses himself; preexisting the plane of ontology is the ethical plane" (TI: 201). And note "epiphany" as opposed to manifestation:

To manifest oneself as a face is to impose oneself above and beyond the manifested and purely phenomenal form, to present oneself in a mode irreducible to manifestation, the very straightforwardness of the face to face, without the intermediary of any image, in one's nudity, in one's destitution and hunger.

(TI: 200)

That the face involves a presentation that is ethical rather than ontological and that is "irreducible to manifestation" undermines the primacy and generality of phenomenology Rather than phenomenon, Levinas sometimes refers to the presentation of the face as an "enigma", a "mystery" of infinite depth or height. No intuition or intuitions, no explication of the meaning of being, no return to phenomena, will ever succeed in dispelling this sense of mystery or in removing this enigma. Husserl was perhaps more correct than he realized in referring to the apprehension of the other as a "puzzling possibility"; where he went wrong, according to Levinas, is in supposing that phenomenology could offer a solution.

Derridas critique of Husserl begins at the very beginning of his phenomenology, with a number of distinctions drawn at the outset of his Logical Investigations. These preliminary distinctions concern the relation between thought and language, between conscious experience and the spoken and written signs used to express that experience outwardly Derridas rather bold contention is that not only the six subsequent investigations but also the entirety of Husserlian phenomenology, including his later "pure" or "transcendental" phenomenology, stand or fall with the validity of these distinctions. To the extent that these distinctions cannot be maintained, then Husserl's phenomenological project fails. In very broad brushstrokes, Derrida argues that Husserl seeks to exclude at the very beginning of his phenomenology anything sign-like at the level of pure consciousness, since pure consciousness, Husserl contends, is immediately available: to the phenomenological investigator without the mediating intervention of signs. Husserl's efforts to maintain this exclusion, however, can be shown to break down, and in such a way as to undercut the very idea of immediacy or presence required by pure phenomenology. What will later be enshrined in Husserl's "principle of all principles" turns out to be an inherited, highly suspect piece of metaphysical baggage, hardly what one would expect from what prides itself as a "presuppositionless" form of enquiry. But if the principle of principles must be abandoned, then Husserl's conception of phenomenology and indeed his entire conception of consciousness must be abandoned too.

The first of Husserl's six "logical investigations" begins with some preliminary but what Husserl considers to be "essential" distinctions, the most fundamental of which is the distinction between expression and indication. At the very beginning of §1, Husserl says "Every sign is a sign for something, but not every sign has 'meaning', a sense' that the sign expresses'" (LI: 269). What Husserl is saying here at first does not sound too complicated or controversial; certainly it does not sound like anything on which the entirety of a philosophical project might depend. Before trying to assess such a claim of dependence, let us first work through how Husserl explicates this distinction. Husserl (see LI: 270) defines the notion of indication in the following way:

X indicates Y for (or to) A when A's belief or surmise in the reality of X motivates a belief or surmise in the reality of Y.

This general notion of indication covers both signs and what might be called "natural indicators". The former include things such as brands

The metaphysics of presence

Derrida sees not just Husserl's phenomenology but the entirety of the Western philosophical tradition as permeated by "the metaphysics of presence". The notion of presence has more than one axis, depending on what it is contrasted with: present as opposed to absent, but also present as opposed to past or future. In Derrida's locution, both senses are in play. The metaphysics of presence involves a privileging of the present, temporally speaking, but there is also a spatial-epistemic dimension, with a conception of presence to the mind or consciousness as the -optimal source of knowledge and understanding. The twin notions of presence are actually intertwined, in the sense that the temporal present represents the optimum for epistemic presence: to know or understand something optimally or fully is to have it present before one's mind in the present (all at once). Descartes's cogito involves this twin notion of presence. The immediacy of "I am, I exist" vouchsafes Descartes's existence, but only in the moment that this thought is entertained. The cogito fails otherwise: "I was in existence" and "I will exist" admit of no certainty whatsoever. Ultimately, one can see in this privileging of presence (and the present) an ultimately theological conception of knowledge and understanding; one way of contrasting divine with merely human understanding is to say that God sees, knows, or understands everything all at once. That human understanding is extended in time is already a mark of its inferiority.

on cattle, which indicate ownership by a particular ranch, flags, which indicate things ranging from nationality to the finish line of a race, and knots in handkerchiefs, which indicate that something needs to be remembered. Some examples of natural indicators are dry lawns, which indicate drought, cracks in the walls of a house, which indicate subsidence, and darkening clouds, which indicate an oncoming storm. The connection between an indicator and what it indicates can thus be a matter of convention, as in the case of signs, or natural, as in the case of natural indicators. Where the connection is not purely conventional, the relation between indicator and indicated could be one of cause and effect (where the "surmise" goes from effect to cause), earlier and later (where there maybe a common cause), probability and so on. In both cases, the connection is empirical and contingent, and is underwritten by habit, generalization and custom. In general, the connection is associative: indicators indicate something by our coming to associate the indicator with the thing indicated. As associative, there is in no case an essential or intrinsic connection between indicator and indicated.

Expression, by contrast, brings in the notion of meaning or sense, which, for Husserl, marks an altogether different relation. Expressions are meaningful signs, which Husserl restricts to linguistic signs, thereby excluding things such as facial expressions and bodily gestures. To get a feel for this distinction, consider the difference between the crying of a baby, which indicates, for example, a wet nappy or the need to eat, and the words "My nappy is wet" or "I'm hungry". Although the crying is associated with wetness and hunger, and so points the one hearing the baby's cry towards such things, the crying still only indicates, without actually saying or meaning "My nappy is wet" or "I'm hungry", whereas the expressions in each case do say and mean something: the expressions are about wetness and hunger, rather than indicators of them. Unlike the merely associative connection between indicators and what they indicate, the connection between expressions and their meaning is an essential one, as the notion of meaning constitutes what it is for something to be an expression.

Linguistic signs, as meaningful, thus involve the notion of expression, but Husserl's conception of language and linguistic signs is a good deal more complicated than this first pass at distinguishing between expression and indication might suggest. Husserl (see LI: 276) has what I am going to call a two-tiered conception of language, consisting of:

For Husserl, (b) is the locus of genuine meaning or sense, whereas (a) is only meaningful in a derivative sense. Notice that sensible, physical signs derive their meaning from mental states by being "associatively linked" with them, which means that linguistic signs involve the notion of indication: linguistic signs indicate, or point to, the mental states that are the locus of genuine meaning or sense. The distinction between (a) and (b) can be further delineated by noting the absence of an essential connection between the sensible, physical signs and the underlying, meaningful expressions. Since expressions are only associatively linked with sensible signs, whatever meaning we accord to sensible signs has a conventional component. On reflection, we can see that it need not have been the case that the string of letters "wet" means wet; had language evolved differently, the concatenation of those three letters may have come to mean something else.

Given this two-tiered conception, Husserl distinguishes between communication and what he calls "solitary mental life". The way communication works for Husserl is as follows. Subject A has certain thoughts he wishes to communicate to subject B. Accordingly, A produces a series of sounds or marks (i.e. words), which A intends to be the outward manifestation (sign, indication) of those thoughts. Subject B in turn perceives these outward signs or indications, and then surmises the mental states of A that A wished to communicate. On this picture of communication, indication plays an essential role; moreover, communication always involves a kind of gap, to be bridged by a "surmise" of the kind one makes in the move from indicator to indicated. What I am trying to express by means of the indicative signs I produce is something my interlocutor needs to figure out. Solitary mental life, by contrast, involves no such gap: "Expressions function meaningfully even in isolated mental life, where they no longer serve to indicate anything" (LI: 269). Such pure expressions, dispensing with the notion of indication altogether, no longer involve the use of words as signs. Indeed, there can be no indicative function for words in solitary mental life, since there is no gap between the mental states and the experience of them. There is nothing to "surmise" or connect by means of an associative link, because the mental states are fully present to the one whose states they are, experienced "at that very moment" of their coming into existence (here we begin to see the way in which Husserl's initial distinction is bound up with a conception of consciousness as presence). Without any use of words as signs, there are, Husserl maintains, no "real" words involved in an interior soliloquy, but only "imagined" ones (see LI: 278-80).

From an initial sharp distinction between expression and indication, we are led to a sharp distinction between language understood as a complex of physically articulated signs and the intrinsically meaningful mental states on which the meaning of language depends. This latter distinction leads in turn to a sharp distinction between communication and solitary mental life. According to Derrida, these sorts of distinctions foreshadow, and indeed animate, Husserl's later explicit articulation of the phenomenological reduction. Indication, as bound up with the empirical, even physical, dimension of language, must be eliminable, leaving only an underlying layer of pure expression, whose essential meaning is unaffected by the elimination of associatively formed connections. In a passage that clearly anticipates the later development of the phenomenological reduction, Husserl makes this eliminability explicit:

It is easily seen that the sense and the epistemological worth of the following analyses [i.e. the six logical investigations] does not depend on the fact that there really are languages, and that men really make use of them in their mutual dealings, or that there really are such things as men and a nature, and that they do not merely exist in imagined, possible fashion.

(LI: 266, emphasis added)

If expression and indication cannot be separated in the way Husserl demands, then that will tell against the possibility of the phenomenological reduction. If the very idea of expression, and so the notions of sense and meaning, ultimately involves indication, then any attempt to isolate a layer or domain of "pure expression" that is fully present without any mediating play of signs will be futile, indeed incoherent. Consciousness, in so far as it involves the notion of meaning or sense, cannot be conceived of as fully and immediately present, even to the one whose consciousness it is. The ineliminability of indication, and so of mediation, undermines any privileging of the present, both in the sense of something's being fully present and in the temporal sense of the present moment.

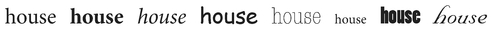

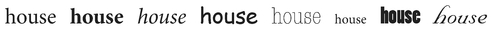

In Speech and Phenomena, Derrida's principal argument against the validity of Husserl's "essential distinction" turns on the notion of "representation", and its role both in Husserl's distinction between pure expression and communication and in language and linguistic meaning more generally. Let us begin with the latter domain. Derrida argues here that all of language involves the notion of representation: "A sign is never an event, if by event we mean an irreplaceable and irreversible empirical particular" (SP: 50). In order for a sign to mean or stand for something, it must participate, so to speak, in something beyond itself: the sign, to be a sign, must serve as a representative of a type, and so cannot be "an irreplaceable and irreversible empirical particular". Consider the following set of signs (words): None of these signs is exactly like the others, in the sense that they all vary in size, shape and in some cases darkness; each one occupies its own region of space and has a slightly different history; each can thus be regarded as in some sense an "empirical particular". At the same time, there is also a very definite sense in which each of these signs is the same sign, that is, the sign "house", and this sense is crucial to each of these variously shaped marks being signs. Another way to put this is to say that all of these signs, in so far as they are signs, are tokens of a single type. Language, as a system of signs, requires this type-token structure, whereby different tokens are recognizable as the same. Every sign, as a sign, must stand for, or represent, or instantiate a type; otherwise there would be no words, phrases, sentences and so on that could be repeated, spoken or written on indefinitely many occasions. Repetition (or what Derrida calls "iterability") is essential to language.

But how do these points about representation and repetition affect Husserl and, in particular, the distinction between expression and indication? Recall that one way Husserl distinguishes communication between two subjects (what he sometimes calls "effective" or "genuine" communication) from "solitary mental life" or "mental soliloquy" is that the latter does not involve the production of "real words". Instead, in mental soliloquizing, there are only "imagined" words, fictitious language rather than the real thing, because the subject has nothing to communicate to itself. The critical question Derrida asks us to consider is what exactly the difference is between real and imaginary signs or language, between genuine and fictitious speech. What are real words, and how do we distinguish real ones from ones that are only imagined? Given his observations about representation and repetition, Derrida's point in raising these questions is to show that these distinctions cannot be maintained. All language or speech, as involving representation and repetition, has an element of fiction to it, in so far as any word one produces stands for an ideal type: "The sign is originally wrought by fiction" (SP: 56). Any linguistic sign one produces is, in some respects, fictitious and, in some respects, real or genuine: no word-instance has any more claim to reality than any other, since any word-instance, to be a genuine word-instance, must represent, stand for or instantiate a word-type, which is ideal rather than real. These requirements hold to an equal degree in the case of imaginary speech and in the case of "effective" communication, and so there can be no principled distinction between the two: whether "with respect to indicative communication or expression, there is no sure criterion by which to distinguish an outward language from an inward language or, in the hypothesis of an inward language, an effective language from a fictitious language" (SP: 56). Representation and ideality belong to "signification" in general, and so imagined speech and genuine speech are structurally equivalent: "By reason of the primordially repetitive structure of signs in general, there is every likelihood that 'effective' communication is just as imaginary as imaginary speech and that imaginary speech is just as effective as effective speech" (SP: 51). The upshot for Husserl is that "solitary mental life", in so far as it involves signification, involves the use of signs in the same way as in the case of effective communication, and since effective communication involves both expression and indication, so too does solitary mental life.

If Derrida is correct that solitary mental lite is pervaded by indication, by the use of signs, then Husserl's appeal to the primacy of presence cannot be sustained. If consciousness is "sign-like", then the very idea of conscious experience involves notions such as representation and repetition, and so anything present to consciousness is bound up with, and depends on, something absent. Whatever there is that is essential to consciousness cannot be grasped, made fully available, within the present, within an "intuition" that is not at the same time founded on what lies beyond it. As developed thus far, Derrida's argument primarily undercuts what we might call the authority of the present in the realm of experience, by showing how any appeal to what is present to consciousness necessarily involves what is absent, and so what is present cannot play any special foundational role. A further consequence of this line of argument is that the very idea of the present moment in experience and, correlatively, of the idea of presence to consciousness, needs to be reconceived, because the way in which the present lacks authority means that it also lacks any kind of autonomy. As Derrida puts it:

If the punctuality of the instant is a myth, a spatial or mechanical metaphor, an inherited metaphysical concept, or all that at once, and if the present of self-presence is not simple, if it is constituted in a primordial and irreducible synthesis, then the whole of Husserl's argumentation is threatened in its very principle.

(SP: 61)

The mythological character of the present moment is already revealed in Derrida's critique of Husserl's characterization of solitary mental life. Solitary mental life was to be understood as the locus of "pure expression" because anything that might be indicated by signs would be understood at the very moment the experience occurred. One cannot tell oneself anything, because there is nothing hidden from oneself that needs pointing out. However, the entanglement of expression and indication means that the present is not a simple given, but is instead a complex compound, an intersection of past and future that is dependent on both: the "presence of the perceived present can appear as such only inasmuch as it is continuously compounded with a non presence and non perception, with primary memory and expectation (retention and pretention)" (SP: 64).

Although the punctuality of the instant is already shown up by Derrida's arguments concerning expression and indication, a particularly intriguing and ironic feature of his subsequent argumentation is the extent to which, according to Derrida, Husserl himself debunks this myth of presence. That is, one strand of Derrida's argument is dedicated to showing how many of Husserl's phenomenological insights, especially those concerning the structure of time-consciousness, tell against his own appeals to the founding role of presence. Hence the idea that Derrida's argument is one that "deconstructs" Husserlian phenomenology, by revealing the ways in which it pulls itself apart. This deconstructive element can be seen in the previous quotation, since "retention" and "pretention" are, after all, Husserlian terms; indeed, they are essential dimensions of his account of the temporal structure of experience. Derrida's point is that Husserl cannot have it both ways. The phenomenological descriptions of the structure of experience Husserl himself provides tell against his very own "principle of all principles". There is no pure experience, either temporally or spatially speaking. Any moment of experience is informed by, refers to, carries traces of or points ahead to other experiences within the ongoing flow. Husserl himself demonstrates this, despite his own continued allegiance to the mythology of presence.

On Derrida's account, consciousness is, we might say, "sign-like", in that whatever is present at any given time is always at the same time indicative of what is non-present. The structure of language, as well as the structure of signification more generally, involves this interplay of presence and non-presence. We can see this in the indicative dimension of signs, which stand for or represent something beyond themselves, their ideal types, but also in the temporally extended character of language use. Speaking, reading and writing all take place over time; sentences have a beginning, a middle and an end, such that what is said and understood is not something that happens all at once. Derrida calls this extended, representational dimension of signification "differance", which incorporates both the idea of differing and that of deferring. All signs involve difference, in the sense that signs are both empirical particulars and yet stand for something other than themselves (signs are, paradoxically, cases of sameness-in-difterence), and the use of signs always involves some kind of delay or deferral, again in keeping with the idea that sense or meaning is never grasped in an instant, but only over time. The play of differance pervades language, but also, in so far as it involves signification, consciousness.

We might also put Derridas view this way: consciousness is, or is like, a text. In one place, Derrida writes that "there is no domain of the psychic without text" (WD, 199), which underlines what I have been calling the "sign-like" character of conscious experience. As text, consciousness consists of an extended flow, any moment of which is informed by, or carries, traces of what lies elsewhere. Consciousness is, in this way, mediated, never immediate, since what is happening now in my experience can never be fully determined or evaluated at the time of that experience; the content and significance of my experience is continually open to revision and reinterpretation.

Derridas debunking of the mythology of presence, and his correlative championing of a textual model of consciousness, signals his allegiance to certain ideas in Freud. That is, the essential role of non-presence and the sign-like nature of any present experience points to a fundamental role for the unconscious in the constitution of consciousness. What is present to consciousness, what is open to me about my own mental life at the moment, is not something free-standing or self-sufficient. What is present are symptoms, which point to or indicate some underlying tendencies, conditions or events. The indicative relation here has just been spelled out in spatial terms, as though the unconscious were lurking beneath the level of conscious experience. There is also, however, a temporal dimension, since what has been repressed, according to Freud, are often childhood wishes, fantasies and fears (usually of a sexual nature). The quotation above concerning the textual character of the psychic comes from Derridas essay, Freud and the Scene of Writing", wherein he both celebrates and interrogates Freud's use of writing as the dominant metaphor for consciousness. For Derrida, Freud, in his discernment of the domain of the unconscious, is the first to appreciate the textual nature of consciousness. We need to be careful here, though, if we are to appreciate just how radical Freud's ideas are (at least as Derrida understands them), since the metaphors of writing and texts still allow for the idea of a kind of "all-at-once" in the sense that the entirety of the text is somehow present and fully formed, even though it is only accessible or available piecemeal. To say that consciousness is a text or text-like does not mean that our experiences are like a big book, where the previous chapters are there, behind the current one, to be returned to as they were at the time they were read. The unconscious does not have that kind of static determinacy, but is itself a dynamic text, to be revised and reinterpreted. The real lesson of Freud, as Derrida reads him, is that:

There is no present text in general, and there is not even a past present text, a text which is past as having been present. The text is not conceivable in an originary or modified form of presence. The unconscious text is already a weave of pure traces, differences in which meaning and force are united - a text nowhere present, consisting of archives which are always already transcriptions. Originary prints. Everything begins with reproduction.

(WD: 211)

That everything begins with reproduction means that there is no recoverable moment of presence, no experience that can be inspected and dissected "just as it is", since experience is "always already" transcribed, mediated, permeated by "pure traces". That "everything begins with reproduction" means that there can be no pure phenomenology. Whether there can still be what Dennett calls "impure phenomenology", however, is another matter altogether. As we shall see, Dennett also develops a textual model of consciousness that, like Derrida's, embraces the idea that "there is no present text in general".

In Part I of Consciousness Explained (and elsewhere), Dennett develops and defends a method for investigating consciousness, what he dubs "heterophenomenology," the principal virtue of which is its adherence to what Dennett sees as scrupulous scientific method. "The challenge is to construct a theory of mental events, using the data that scientific method permits" (CE: 71), and what that method allows as data is what is in principle available to a third-person, neutral investigator. In this sense, Dennetts approach to consciousness employs an "outside-in" strategy: the data deemed reliable are those that can be gleaned from a perspective external to the agent whose "consciousness" is under investigation (the reason for the inverted commas will become apparent as we proceed).

Dennett's cautious approach is fostered by his sense that consciousness is a "perilous phenomenon", which provokes "skepticism, anxiety, and confusion" in those who so much as contemplate its study (HSHC: 159). The dangers attending the study of consciousness are due in large part to the legacy of what Dennett sees as so many failed attempts. Like an imposing, yet alluring, mountain littered with the bodies of those who try to scale its heights, consciousness remains elusive in spite of the many efforts of philosophers, psychologists and neuroscientists. Of these three groups who seek to understand and explain consciousness, the failures of the first, the philosophers, have been especially egregious, primarily because of an entrenched but highly problematic set of assumptions about how consciousness both can and must be studied. For Dennett, the phenomenological tradition quite clearly exemplifies these shortcomings, and Dennett thinks that attention to the failings of phenomenology help to motivate the kind of approach to consciousness he recommends.

Although phenomenologists, principally Husserl, endeavoured "to find a new foundation for all philosophy (indeed, for all knowledge) based on a special technique of introspection in which the outer world and all its implications and presuppositions were supposed to be 'bracketed' in a particular act of mind known as epoche" (CE: 44), the exact nature and results of such a "technique" were never completely determined, and so phenomenology "has failed to find a single, settled method that everyone could agree upon" (CE: 44). Dennett's suspicions concerning the merits of phenomenology are fostered by this failure to secure agreement, prompting him instead to found a method inspired by disciplines where at least some agreement has been secured and more is promised: the natural sciences. In stark contrast to the natural sciences, where practitioners can be confidently ranked in terms of their expertise, the failures of phenomenology allow for no such ranking, which leads Dennett to make the following, striking claim: "So while there are zoologists, there really are no phenomenologists: uncontroversial experts on the nature of the things that swim in the stream of consciousness" (CE: 44-5).

Delimiting just what those "items in conscious experience" are is, for Dennett, a delicate matter, particularly in the wake of phenomenology's demise: the absence of experts means that there is no uncontroversial inventory of what "swims" in the stream of consciousness. Indeed, the persistence of "phenomenological controversies", in spite of the wellentrenched philosophical idea that "we all agree on what we find when we 'look inside' at our own phenomenology" (CE: 66), indicates that we must "be fooling ourselves about something" (CE: 67). In particular, Dennett argues that "what we are fooling ourselves about is the idea that the activity of 'introspection is ever a matter of just 'looking and seeing'" (ibid.). Instead, "we are always actually engaging in a sort of impromptu theorizing - and we are remarkably gullible theorizers, precisely because there is so little to 'observe' and so much to pontificate about without fear of contradiction" (CE: 67-8).

According to Dennett, then, there are far fewer things swimming in the stream of consciousness than has traditionally been thought; indeed, what is taken to be there is not so much ascertained by introspective observation, as it is postulated retrospectively through largely creative acts of interpretation (the "impromptu theorizing" to which Dennett thinks we all are prone). That theorizing, moreover, even when it has the "feel" of observation, is as liable to error as any other, perhaps more so despite the fact that what one is theorizing about is one's own conscious experience. Rather than having the kind of certainty often conferred on it, Dennett sees the process of introspective self-interpretation as fraught with a whole host of pitfalls, due largely to the temporal lags between alleged states of consciousness and the introspective cataloguing and reporting of them. Within those lags, Dennett thinks, there is room for all sorts of errors to occur: "The logical possibility of misremembering is opened up no matter how short the time interval between actual experience and subsequent recall" (CE: 318). Dennett's criticisms apply not just to Husserl, but also to Sartre, at least at the time of The Transcendence of the Ego. Recall Sartre's conception of phenomenological method as "conspiring" with one's own conscious experience, which requires recreating the experience while tagging along with it. In his account of this procedure, Sartre claims, without argument, that it is "by definition always possible" to "reconstitute the complete moment" (TE: 46) of unreflected consciousness. Dennett's challenge to Sartre is to provide criteria for adjudicating among different and conflicting attempts at reconstitution. Since the original experience is long gone, how does one know and how can one show that one's current reconstitution of that experience is accurate, let alone "complete"?

The retrospective dimension of introspection creates one possibility of error. What I now think I thought back then may perhaps be different from what I actually thought at the time, although because I now think I thought it then, it will seem exactly as if I did back then as well. Such errors are thus highly recalcitrant when one is restricted to a first-person perspective. Misremembering, however, is not the only way in which one can get things wrong about one's own experience. Hi at conscious (and other mental) states admit of the possibility of embedding, such that I can, for example, form judgements about how things seem and so forth, provides ample opportunity for mistakes to arise: "Might it not be the case that I believe one proposition, but, due to a faulty transition between states, come to think a different proposition? (If you can 'misspeak', can't you also 'misthink'?)" (CE: 317). As there is so much room for speculation, fabrication and misperception, introspection provides little in the way of a solid foundation for a properly scientific investigation of consciousness. Hence Dennett's preference for heterophenom enology, rather than the traditional auto- variety; consciousness is best approached from the outside, standing on the banks of the stream, as it were, rather than swimming along introspectively.

In many ways, Dennetts method is the mirror image of the Husserlian one. Whereas Husserl's phenomenology begins with the epoche, wherein commitment to the reality of the external world, including oneself as a denizen of that world, is suspended or "bracketed", the heterophenomenological method begins by bracketing any commitment to the reality of consciousness. The scientific investigator is to adopt as neutral an attitude as possible with respect to his subjects: "Officially, we have to keep an open mind about whether our apparent subjects are liars, zombies, parrots dressed up in people suits, but we don't have to risk upsetting them by advertising the fact" (CE: 83). Strictly speaking, then, heterophenomenology does not study conscious phenomena, since it is neutral with respect to the question of whether there are any. Its subject matter is instead reports of conscious phenomena: the actual transcripts produced in a laboratory setting recording what the "apparent subjects" say about their "experience". Indeed, even taking the noises emitted by these apparent subjects to amount to things they say is already a bold leap beyond the given: "The transcript or text is not, strictly speaking, given as data, for ... it is created by putting the raw data through a process of interpretation" (CE: 75).

Having worked up the raw data into reports, the heterophenomenologist proceeds by exploring the possible relations between those reports and other data that are likewise accessible (at least in principle) from this external vantage-point, namely, the goings-on in the apparent subjects brain and nervous system. Dennett likens the investigator s approach here to one we might take towards a straightforwardly fictional text. Although we regard the "world" of that text as fictional, we might nonetheless look for "real-life" correlates of the text, for example, contemporaries of the author who may be considered the inspiration for characters in the work,

The intentional stance

A key feature of Dennett's heterophenomenological method is his notion of the "intentional stance", which the heterophenomenological investigator adopts when he chooses to treat the "noises" emitted by his subjects as meaningful words and reports. Rather than thinking of intentionality as a property or feature of an organism (or machine) in and of itself Dennett instead recommends thinking of intentionality as a feature of how we view an entity, of what attitude or stance we take towards it and what it does. Very often, adopting the intentional stance towards an entity or range of events will yield far more in the way of predictive success, while another, such as the physical stance, will afford little in the way of useful insights. For example, someone who had adopted the intentional stance would detect a connection between someone's emitting the noise "Hello" and someone's waving his or her arm. Although the physics of these two events is wildly different, from the intentional stance they can both be located as forms of greeting, and will accordingly generate reliable predictions that the physicist can scarcely imagine. What the intentional stance renders discernible are very often "real patterns", but considerable care is needed in cashing out this idea. Some of these "patterns" are cases where we are reluctant to identify them as involving genuine intentionality. For example, one can take up the intentional stance towards a simple thermostat, attributing to it a small array of "beliefs" about the room (such as "too hot", "too cold" and "just right"), along with another small array of "desires" to change the temperature of the room in one direction or another. While one can take such a stance towards the thermostat, and even though we do often talk this way about things like machines and plants, such talk usually strikes us as loose, figurative or even metaphorical. These are cases of "as-if" intentionality, and so we stop short of treating them as instances of the "real thing" Although we can often feel confident about identifying a pattern as an instance of only "as-if" intentionality, and equally confident with respect to sortie instances of the "real thing", the thorny issue, according to Dennett, is one of how to make a principled demarcation between the two. There is, he contends, no clean and clear dividing line between the "as-if "cases and the genuine ones, and he suggests instead that we should see the difference as one of (admittedly very great) degree rather than kind.

or events in the author's biography that have been reworked to play a role in the dramatic narrative. Dennett's investigator likewise treats all of his worked-up reports as portrayals of "heterophenomenological worlds", populated by a range of fascinating characters: all those putative phenomena of consciousness. In so treating the reports, the heterophenomenolo gist regards these phenomena as strictly analogous to the characters in fiction. He does not take them as standing for real-life denizens of the world, at least not in any straightforward sense. At best, he regards them as cleverly disguised, reinterpreted versions of what is really going on in the brain. To the extent that Dennett's investigator can find sufficient connections between the population of the heterophenomenological world and the goings-on in the brain, he will (always tentatively) see the latter as the real topic of the reports.

Given this further articulation of Dennett's method, we can grasp more fully the reasons behind his distrust of introspection, as well as see more clearly the diagnosis of the weaknesses of peoples "impromptu theorizing". If introspection is really a matter of theorizing, and if the proper objects of this theorizing are really objects and events in the brain, then small wonder that people's reports are unreliable, indeed often wildly inaccurate. After all, very few of us, even those of us who are well educated in other respects, have detailed knowledge of the workings of the brain and nervous system. Moreover, our usual predicament is such that those workings are generally obscured from view, that is, we are not in general well positioned to observe the workings of our own brain in any direct fashion. Thus, "what it is like to [us] is at best an uncertain guide to what is going on in [us]" (CE: 94). The indirect route of introspection is all each of us usually has to go on, and if Dennett is right it is a circuitous route indeed, much like the approach of reading Victorian novels, say, as a means for learning the historical facts of that era. The standard first-person authority championed by the philosophical, and especially the phenomenological, tradition is thus severely restricted:

If you want us to believe everything you say about your phenomenology you are asking not just to be taken seriously but to be granted papal infallibility and that is asking too much. You are not authoritative about what is happening in you, but only about what seems to be happening in you.

(CE: 96)

The results of Dennett's heterophenomenology are at least as radical as the method, if not more so. Indeed, Dennett acknowledges that his view is initially deeply counterintuitive, as it requires a radical rethinking of the familiar idea of 'the stream of consciousness"' (CE: 17). In keeping with Dennett's speculation that there is less to introspect than has standardly been thought, the "stream of consciousness" is perhaps better understood as a scattered system of rivulets. What Dennett dubs the "Multiple Drafts" model of consciousness maintains that "at any point in time there are multiple 'drafts' of narrative fragments at various stages of editing in various places in the brain" (CE: 113). There is, on this model, a constant process of "additions, incorporations, emendations, and overwritings of content [which] occur, in various orders", and what "we actually experience is a product of many processes of interpretation - editorial processes, in effect" (CE: 112). Although talk of "multiple drafts" carries connotations of a series of processes culminating in a finished product, as takes place in the writing process from which Dennett borrows his terminology, the radicality of the model is precisely the denial of this suggestion: "Most important, the Multiple Drafts model avoids the tempting mistake of supposing that there must be a single narrative (the 'final' or 'published' draft, you might say) that is canonical - that is the actual stream of consciousness of the subject" (CE: 113).