Two worms lived in shit, a father and son. The father said to his son, “Look at the wonderful life we have. We have plenty to eat and plenty to drink, and we are protected from outside enemies. We have nothing to worry about.” The son said to his father, “But father, I have a friend who lives in an apple. He also has plenty to eat, plenty to drink, is protected from outside enemies, and, he smells good. Can we live in an apple instead?”

“No, we can’t,” replied the father.

“Why?” said the son.

“Because, my son, the shit is our country.”

The House with the Ocean View had been so difficult and demanding that I was ready for a change of pace. And so when the British curator Neville Wakefield told me he was asking twelve artists to create a work on the subject of pornography, it sounded relatively easy and fun—at first. Then I looked at a few pornographic movies, which were a total turnoff. Instead I decided to research Balkan folk culture.

First I examined the ancient origins of eroticism. Every myth and folktale I read seemed to be about humans trying to make themselves equal with the gods. In mythology, woman marries the sun and man marries the moon. Why? To preserve the secrets of creative energy and get in touch with indestructible cosmic forces.

In Balkan folk culture male and female genitals have a very important function in both healing and agricultural rites. In Balkan fertility rituals, I learned, women openly displayed their vaginas, bottoms, breasts, and menstrual blood; men uninhibitedly displayed their bottoms and penises, engaging in masturbation and ejaculation. The field was very rich. I decided to make both a two-part video installation and a short film about these rites: I called the pieces Balkan Erotic Epic. In the summer of 2005 I went to Serbia to begin the project. It would take me two years to cast the participants, and it wasn’t easy. But the Baš Čelik production house, and their amazing production director Igor Kecman, made possible everything that seemed impossible in the sometimes corrupt and dangerous environment of ex-Yugoslavia.

In the film I played the role of professor/narrator, describing each ritual, then having it reenacted. Some of the rites were so bizarre that I couldn’t imagine persuading people to participate, so I turned them into short cartoons: for instance, if the woman wants her husband or lover never to leave her, she takes a small fish in the evening, puts it in her vagina, and goes to sleep. In the morning, she takes the dead fish out of her vagina, grinds it into a powder, and puts this powder into her man’s coffee.

For the live scenes I enlisted people who had mostly never been in front of a camera before. I crossed my fingers when I put out a casting call for women between the ages of eighteen and eighty-six to show their vaginas to scare the gods in order to stop the rain. And it was equally difficult to find fifteen men who would be willing to be filmed in national uniforms, standing motionless with their erect penises exposed while the Serbian diva Olivera Katarina sang, “O Lord, save thy people…War is our eternal cross…Long live our true Slavic fate…”

I acted in a couple of scenes myself. In one I was bare-breasted, with all my hair combed forward over my face: my head looks as if it is on backward. In my hands is a skull. I hit my stomach with the skull again and again and again, faster and faster and faster, in a kind of frenzy. The only sound is the slap of the skull against my flesh.

Sex and death are always very close in the Balkans.

While I was in Belgrade working on this project, Paolo, who had accompanied me, was making a video of his own: a simple but powerful piece showing a boy playing soccer with a skull in the ruins of the Yugoslav Defense Ministry, which had been bombed during the Kosovo war. To our delight, Paolo’s video was selected for the 2007 Venice Biennale—and then the Museum of Modern Art in New York announced it was adding the piece to its permanent collection.

To celebrate this milestone, I made a deal with the collector Ella Fontanals-Cisneros: I gave her a first-edition photograph of me in Rhythm 0, and in exchange she chartered a yacht on which I gave Paolo a big surprise party in the Venice lagoon, inviting all our friends and everyone I knew from all the Biennales I’d participated in. He was overwhelmed by all the attention and the many compliments on his video. He really felt he had arrived. And I thought—but I did not say—that it takes much more than one successful piece to arrive.

Balkan Erotic Epic was a way to explore something completely new during the time I had been preparing a huge and complicated performance for the Guggenheim, ironically titled Seven Easy Pieces. For a long time I had felt the need to re-create some important performances from the past, not just my own but those of other artists as well, in order to bring these pieces to a public that had never seen them. I first proposed the idea in 1997, soon after Balkan Baroque, to Thomas Krens, then the director of the Guggenheim. I wanted to open a discussion about whether performance art could be approached in the same way as musical compositions or dance pieces—and also to examine how performance can best be preserved. After thirty years of performing I felt it was my duty to tell the story of performance art in a way that would respect the past and also leave space for reinterpretation. By re-performing seven important pieces, I told Krens, I wanted to propose a model for the future for reenacting other artists’ performances. He loved the idea, and appointed the brilliant Nancy Spector to curate it.

I set several conditions for the show: first, to ask the artist (or, if the artist was dead, his or her foundation or representative) for permission; second, to pay the artist a copyright fee; third, to perform a new interpretation of the piece, always acknowledging the source; and fourth, to exhibit the original performance video and relics.

To a certain degree my idea was motivated by indignation. Performance material and images were constantly being stolen and put into the context of fashion, advertising, MTV, Hollywood films, theater, etc.: it was unprotected territory. I strongly felt that when anybody takes an idea of intellectual or artistic value from someone else, they should do so only with permission. To do otherwise is to commit piracy.

Also, there had been a certain community around performance in the 1970s; by the 2000s, it was completely lost. I wanted to revive this community, and my very ambitious idea was to do it singlehandedly in a seven-day show in which I would perform some important pieces that I’d never seen by other artists from the 1960s and ’70s, along with one of my own. I also wanted to create a new performance for the exhibition. Susan Sontag and I had a long conversation about this work: she was very interested in writing something about it. Unfortunately, she died before Seven Easy Pieces came to fruition. I dedicated all seven pieces to her.

The pieces I originally chose were Bruce Nauman’s Body Pressure; Vito Acconci’s Seedbed; Valie Export’s Action Pants: Genital Panic; Gina Pane’s The Conditioning, First Action of Self-Portraits; Chris Burden’s Trans-fixed; and my Rhythm 0 and a new piece, Entering the Other Side.

Doing my pieces would turn out to be the easy part. Getting permission for some of the others was hell. For example, I really wanted to perform Trans-fixed, the famous 1975 piece by Chris Burden in which he was crucified—golden nails driven through his hands—while lying on the roof of a Volkswagen. But no matter how many times I asked, Burden kept saying no. He wouldn’t tell me why. Much later, I met him and asked, “Why wouldn’t you give me permission?” He said, “Why did you need permission? Why didn’t you just do it?” Which made me realize he’d completely missed the point.

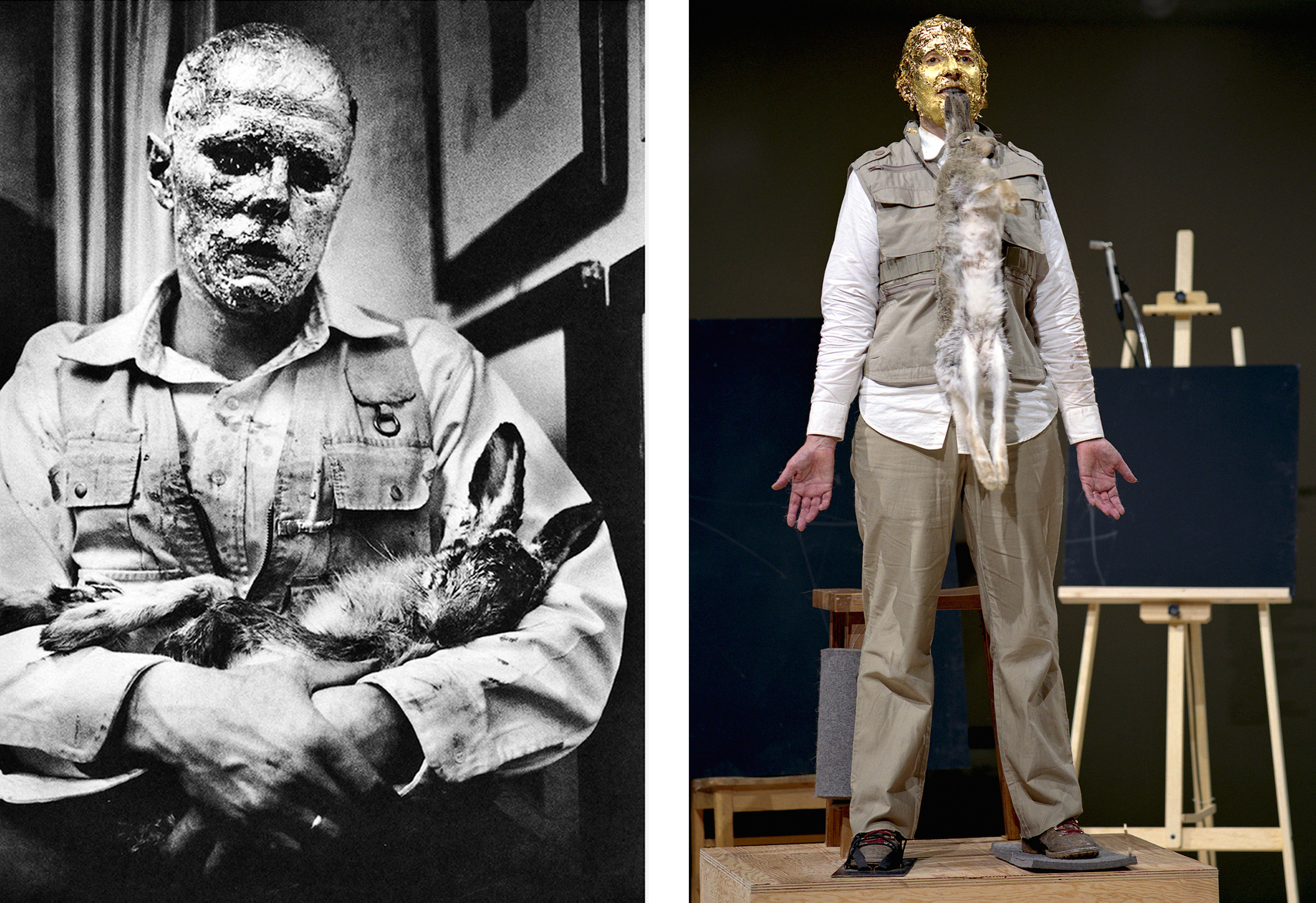

To substitute for the Burden, I chose Joseph Beuys’s great performance How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare, in which he sat like a twentieth-century Pietà, his head covered with honey and gold leaf, and murmured softly into the ear of the dead hare he cradled in his arm. But though the Guggenheim sent Beuys’s widow (he died in 1986) many letters, she kept saying no.

I flew to Düsseldorf and rang Eva Beuys’s doorbell in the middle of a snowstorm. She opened the door and said, “Frau Abramović, my answer is no, but it is cold so you must come in for a coffee.”

“Frau Beuys, I don’t drink coffee but I would love some tea,” I said. I stayed for five hours. At first Beuys’s widow kept saying no—she had thirty-six lawsuits against people who’d been stealing her husband’s work, she told me. But when I told her about some similar problems I had had—a number of images from my solo pieces and pieces I’d done with Ulay had simply been appropriated by artists, fashion magazines, and other media—she began to understand my intentions. Finally she not only changed her mind, but also showed me old videos from this piece that nobody had ever seen. These videos were a big help in my reconstruction of the piece.

Left: How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare, Joseph Beuys, Galerie Schmela, Düsseldorf, 1965; right: me re-performing How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare as part of Seven Easy Pieces (performance, 7 hours), Guggenheim Museum, New York, 2005

The difficulty came when we had to find a dead hare for me to perform with. Animal-rights activists took a big interest in this piece. The museum and I had to prove the dead hare had died a natural death the night before it was delivered to the performance. In the end I was given, five minutes before the performance, a frozen dead hare which had been hit by a truck the night before on a Texas highway. As the performance lasted seven hours, the hare started to defrost as I held it, becoming softer and softer, feeling almost alive. At one point, I held the dead hare by its ears with my teeth. It was heavy and I accidentally bit off the tips of the ears. Its fur was stuck in my throat during the whole rest of the piece.

The important thing for me to explain when seeking permission from each of the artists was that my agenda for the reenactment was not commercial. The only reproductions that could be sold, I said, would be of my work. In this way, I was able to get permission not only from Eva Beuys, but from Vito Acconci, Valie Export, Bruce Nauman, and the estate of Gina Pane. Because I couldn’t get permission from any lawyer to use the pistol required to perform Rhythm 0, I gave myself permission to re-perform Thomas Lips.

This piece became more complicated and autobiographical. I added elements that had significance in my life: the shoes I wore, and the walking stick I used to walk the Great Wall (the stick became 15 centimeters shorter over the course of the walk); the partisan cap with a red Communist star that my mother had worn during World War II; the white flag I carried in The Hero, the piece dedicated to my father; the Olivera Katarina song that I used in Balkan Erotic Epic.

I had originally performed Thomas Lips for one hour; now I was doing it for seven hours. Each hour I had to cut a star in my stomach, and each hour I had to lie naked on blocks of ice. It was a very difficult and demanding piece, and the first time I performed it, in 1975, I was still in my twenties. But now, though I was about to turn sixty, I found that my willpower and concentration were stronger than they’d been almost forty years earlier.

The night I finished re-performing Thomas Lips, the museum guards threw the blocks of ice onto the street. Later I learned that some Brooklyn artists had collected the ice with my blood and sweat, melted it, and tried to sell it as Abramović Cologne. I got one bottle for free.

Over seven days that November, the community I’d longed for came together again at the Guggenheim. Every evening, from five P.M. to midnight, people came to the museum, watched the performances, went out for dinner, came back with friends. And Paolo was there for me each night, giving me crucial support. The crowds got bigger each day. Strangers standing and watching my performances in the rotunda talked to each other about what they were seeing. Connections were formed.

There were some funny moments during the performances. Acconci’s Seedbed—in which I lay hidden under a platform and masturbated to sexual fantasies that I spoke aloud while visitors walked over the platform—was the second piece I performed, after the Bruce Nauman. I achieved eight orgasms, and was so exhausted that I needed every bit of my energy, and some more besides, to perform Valie Export’s Action Pants: Genital Panic the next day.

My performance of Export’s piece happened to fall on Veterans Day, and at the time, the Guggenheim also had an exhibition on Russian icons. In Genital Panic, I wore crotchless leather pants, with my genitals exposed, and held a machine gun pointed at the audience. This was a very provocative piece, which Export had performed in the early ’70s: I never saw it, but I was fascinated by its courage, and intrigued by the relevance of performing it on Veterans Day 2005—many works in the history of art become dated, but this piece had not.

This was also a weekend, and many Russian families came to see the icon show with children. When they arrived, someone called the police. The complaint wasn’t about my exposed vagina, but because I was pointing a machine gun at the icons.

In the case of Gina Pane’s The Conditioning, the part of the piece in which she lay on a metal bedframe over lighted candles had originally lasted eighteen minutes. As I wanted to give my own interpretation to all the pieces, I turned The Conditioning into a long-durational work, lasting seven hours instead of eighteen minutes. And, since I never rehearsed any of the pieces I performed (I only had the concept and the documentation material), I didn’t realize how difficult it would be to lie over candle flames for seven hours. At one point, my hair almost caught on fire.

Left: Action Pants: Genital Panic, Valie Export, Munich, 1968, performance photograph, Munich, 1969; right: me re-performing Action Pants: Genital Panic as part of Seven Easy Pieces (performance, 7 hours), Guggenheim Museum, New York, 2005

The seventh piece, on the seventh day, was Entering the Other Side. I stood high above the rotunda on a twenty-foot platform, wearing a blue dress with a giant, circus tent–like skirt whose spiral form (inspired by the Guggenheim itself) covered the scaffolding and draped down to the floor. The Dutch designer Aziz had created the dress from 180 yards of material and generously donated it to me. As I stood there, I waved my arms in slow, repetitive motions. The room was completely silent for seven hours. Because of the rush to put me on the platform in time for the opening, no one had thought to give me a safety belt—and I was so exhausted after performing for seven days, seven hours a day, that I could have fallen asleep standing—and literally fallen—so it was crucial to stay awake and in the moment. Finally, close to midnight, I spoke.

“Please, just for the moment, all of you, just listen,” I said. “I am here and now, and you are here and now with me. There is no time.”

Then, at the stroke of twelve, a gong sounded, and I climbed down inside the giant skirt and emerged to greet the audience. The applause went on and on; there were tears in many eyes, including mine. I felt so connected to everyone there, and to the great city itself.

![]()

Paolo and I had been together for almost ten years, and the years had been good. The best times were our leisure hours: traveling (we went to India, Sri Lanka, and Thailand, visiting Buddhist monasteries and studying different cultures), going to the movies, making love, vacationing at our house in Stromboli. The hard parts had to do with our very different attitudes about work.

At the beginning of our relationship, just after I won the Golden Lion in Venice, Paolo said to me, “You’ve achieved the pinnacle—you don’t have to prove anything more. Now you can relax! Why don’t we just have a good life?” But I didn’t know what good life he was talking about—for me, the good life was working, and creating.

He had a different rhythm. When we first moved to New York, I wanted so badly to make it, and I worked so hard. I would wake up at five thirty A.M. and Tony, my trainer, would come to the loft, then I would go to work. Paolo would wake up at eight o’clock and have breakfast, read the newspaper, go to the flea market to look for objects he liked. For the first two years he was just exploring the city—and I was just working.

Then in the evening—it was a very sexual relationship. He really needed to have sex every night, and there were times I just didn’t feel like it. It turned into an obligation, and I could not stand it. Simply I was just tired.

I loved Paolo, and I knew he loved me. But at the same time, I knew that if I stopped working, our entire household would stop. I was holding everything together—paying the rent, taking care of our lives, keeping it all running. And everything was functioning: it felt perfect to me. But then one day he told me, “We don’t need any of this. We can just live simply.”

And I knew I couldn’t do that. Because to me, we are each put on earth for a purpose, and we must each fulfill this purpose. Yes, I had won the Golden Lion at fifty—and created The House with the Ocean View at fifty-five, and Seven Easy Pieces at fifty-nine. And soon I would turn sixty, but I knew I still had a lot of work to do.

Living simply is also not in the cards when you’re a couple of artists trying to make it on the New York scene. We threw lots of parties in our apartment, for artists and writers and all kinds of interesting people. And as we became known, we began to be invited to many parties. We were walking on red carpets for the first time.

Although Paolo and I had different feelings about work, we were still very much in love. One day we were grocery shopping at Gourmet Garage on Mercer Street, and as we came out into the rain, Paolo put his bags down, knelt on the sidewalk, and proposed. In the spring of my sixtieth year, the answer came easily: I said yes. I truly felt I would’ve had a child with him if I had been younger.

One day, a few days before our wedding, he went out after lunch and didn’t come back until evening. He walked in with a mysterious smile on his face and turned on music. As the sound of Frank Sinatra singing “I’ve Got You Under My Skin” filled the room, Paolo rolled up his sleeve and showed me the tattoo he’d just gotten: “Marina,” circling his left wrist. He held me in his arms and whispered, “Now I have you under my skin.”

It was a tiny ceremony, with a judge, held opposite the Metropolitan Museum of Art in the beautiful townhouse of the dermatologist Catherine Orentreich, whose father had founded Clinique. Sean Kelly was the best man, and Stefania Miscetti, Paolo’s gallerist at the time and the woman who’d introduced us, the maid of honor. Just a few friends were there: the Kellys, Chrissie Iles, Klaus Biesenbach; Alessia Bulgari, a few others. (A couple of months later, over the summer, Paolo’s parents, who hadn’t been able to make the trip and who really loved me, gave us another wedding, a very large one, in a beautiful house in Umbria.) It was a brilliant April morning, and it felt like a new beginning.

Paolo with my name tattooed on his wrist

For my sixtieth birthday, on the other hand, nothing small would do. Since the Guggenheim hadn’t paid me anything for Seven Easy Pieces, Lisa Dennison, the museum’s new director, agreed to let me use the Guggenheim’s rotunda for my party. I invited 350 people: friends and colleagues from around the world, including the Kellys, of course; my friend Carlo Bach of illy (which sponsored the party and produced a mug called “Miss 60” featuring a pin-up version of me, given away to the lucky guests!), Chrissie Iles, Klaus, Björk, Matthew Barney, Laurie Anderson and Lou Reed, Cindy Sherman, David Byrne, Glenn Lowry and his wife Susan, David and Marina Orentreich and David’s sister Catherine, my new friends Riccardo Tisci of Givenchy (who designed my dress for the occasion) and Antony Hegarty (now Anohni)—and once more, the sharer of my birthday, Ulay. Now that we had a contract, everything between us seemed fine.

The evening was nothing short of amazing. Ektoras Binikos designed a special cocktail, each glass containing one of my teardrops, and there were many great toasts. Björk and Antony sang “Happy Birthday” to me, and then Antony alone sang “Blue Moon” and Baby Dee’s “Snowy Angel,” a song that just pierced my heart, and still does.

With Laurie Anderson at Danspace Project Spring Gala, St. Mark’s Church, New York, 2011

![]()

My mother, now eighty-five, had been declining physically and mentally for a couple of years, and now, in the summer of 2007, she was in the hospital in Belgrade. In my heart I knew she was dying, even though I didn’t want to admit it to myself. The last time I’d seen her, in her apartment, I’d had the feeling that she was sleeping in her armchair rather than her bed. Why? I think she was terrified to lie down—afraid that if she lay down, she would die.

Now she was lying down all the time, immobilized and sinking into senility. Hospitals are such fucked-up, disorienting places that they drive people crazy anyway. She called the masseur I hired for her “Velimir”—in part, I’m sure, because my brother, who lived close to the hospital, rarely, if ever, visited her. My aunt Ksenija took care of her every day; I flew in from New York once a month.

Danica was more and more out of her mind, but she remained ever the tough old partisan. I could see when the nurses turned her that her bedsores were truly awful: the flesh was rotten; her spine was literally exposed. But when I asked her how she was, her answer was always the same: “I’m fine.”

“Do you feel any pain, Mama?”

“Nothing hurts me.”

“Do you need anything?”

“I don’t need anything.”

It was more than stoicism: all her life, she (along with the rest of her family) had avoided discussing anything unpleasant. If I brought up politics—and I did frequently—she would immediately change the subject. “Oh, it’s very warm today,” she would say. Tragedy was off the table. When her younger brother, my uncle Djoko, was killed in a terrible car crash in 1997, my mother never called me to tell me. (She also never told my grandmother, who was made to believe—and never stopped believing until the day she died—that her son had gone on a long business trip to China. Once a month, without fail, my mother and her sister would fabricate a “letter from China” from their late brother and read it to their mother.) Then six months later, I was at the Venice Biennale, and a friend of mine said, “Oh, I saw your mother; she’s really not looking well after this tragedy.” I said, “What tragedy?” Then I called her. It drove me crazy.

But I think perhaps it was this very avoidance that caused her to seek a richer, deeper life—a life that was outside her terrible marriage.

After an especially difficult visit with my mother that July, I flew back home. Every morning I would call the hospital, though Danica could no longer speak coherently, just to ask a nurse to hold the phone up so I could hear whatever she was saying. Then one day, when I called with the usual request—“Can I hear my mother talking?”—the nurse said, “No. Nobody’s in the room.”

It was August 3, 2007. Shortly afterward I got a call from my aunt saying my mother had died early that morning. I asked if Velimir knew; Ksenija said no. So Paolo and I flew to Belgrade. Paolo, Ksenija, and I went to the morgue to identify my mother’s body. She was lying there, covered with a dark-gray sheet. The mortician came in and said, “We didn’t wash your mother’s face yet, and we didn’t shut her mouth. If you give us one hundred euros we will do this for you.”

Oh, my country.

None of us had that much cash with us. So this man pulled the sheet aside. My poor mother had fluids and blood all over her face, and her mouth was wide-open: this was the dead screaming at me. The worst part was touching her hand—the coldness of a dead body is indescribable. I started crying uncontrollably; Paolo held me in his arms. I was so glad he was there for me.

I made arrangements for the funeral. My aunt wanted a church funeral, but my mother had been an atheist and a partisan. So I made a compromise: first we would hold a funeral in an Orthodox church, then everybody would come outside and there would be soldiers shooting rifles. I didn’t sleep at all that night. In the middle of the night I called Velimir, whom I hadn’t talked to for several years, and said, “This is your sister, our mother is dead—come to the funeral.” He arrived at the funeral one hour late and drunk.

Sometimes what the dead leave behind tells us things our dear ones would never have revealed to us while they were alive. After my mother died I went to her apartment to clean up and found a collection of medals she’d been awarded as a national hero. I also discovered a trove of letters and diaries that showed me a Danica I never knew.

With Paolo at my mother’s funeral, Belgrade, August 2007

For one thing, she had a lover. My mother! It was in the early and mid-1970s, during the time she was traveling to Paris for UNESCO. The letters were so passionate, so filled with emotion. He called her “my dear beautiful Greek woman”; she called him “my Roman man.” My mouth fell open and my eyes filled with tears as I read.

Her diaries were just as heartbreaking. One entry from that same time period read, “Thinking: If animals live a long time together, they start loving each other. But people start hating each other.” That shook me to my core, not only for what it said about my parents’ lives, but for what it might say about mine.

And how could I account for the detailed list she had compiled of every mention of my work in the press in the late 1960s and early ’70s? From which (and also from the books about me that I had sent her) she had edited by carefully cutting out every last nude picture of me—so, I’m sure, she could show me off to her friends without shame. It reminded me of the way my father had cut Tito out of their photos together.

What a profound mystery the human heart is.

After Danica’s death her friends told me how when they went out together in a group, my mother had always been the most outspoken and the funniest, the one who told the best jokes. It made no sense to me. I had never, never seen any trace of that in my mother. We had never had a moment that was normal, easy, or relaxing—except twice: There was the incident with the umbrella and the plastic bags. And there was a time, when I was visiting her, when I saw her smiling happily. “Why are you smiling?” I asked her. “Because that woman is dead,” she said. She was talking about my father’s wife, Vesna.

I read these words at Danica’s funeral:

My dear, honest, proud, heroic mother. I didn’t understand you as a child. I didn’t understand you as a student. I didn’t understand you as an adult until now, in my sixtieth year of life, you started shining in the full light like a sun that suddenly appeared behind gray clouds after rain. For ten full months, you were lying motionless in a hospital, and suffering in pain. Whenever I asked you how you were, you said, “I am fine.” When I asked you if you were in pain, you said, “Nothing hurts me.” When I asked you if you needed anything, you said, “I don’t need anything.” You never, ever complained, either of loneliness or of pain. You raised me with a strong hand, without much gentleness, so as to make me strong and independent and teach me discipline, never to stop, never to halt myself until the task is completed. As a child, I thought you were cruel and that you didn’t love me. I have never understood you until now, when I found your diaries, notes, letters, and memories of war. You never spoke to me about the war. I didn’t know of all the medals you had, the ones I found at the bottom of the case in your room.

Right here, standing at your open grave, I wish to mention just a single event from the many of your life. Belgrade was being liberated for seven days, and there were fights for every street, every building. You were in a truck with five nurses, a driver, and forty-five badly wounded partisans. You were driving through gunfire, through Belgrade, towards Dedinje, which was already free, so as to take the wounded to hospital. The truck is shot full of holes, the driver is killed, and the truck is burning. You, chief nurse of the First Proletariat Brigade, jump off the truck, together with the five nurses, and with incredible strength pull all forty-five wounded from the burning truck and lay them onto the pavement. You take the radio telephone and ask for another truck to be sent. The hell of war is burning around you. Another truck is coming. The six of you are getting the wounded in, and four nurses are killed in the process, their bodies filled with bullets flying around them. You and the remaining nurse manage to load all the wounded in the new truck, and break through to the hospital so forty-five lives get saved. Your medal of honor remains a confirmation to this story.

My dear, honest, brave, heroic mother. I love you endlessly, and I am proud to be your daughter. Here at your grave, I wish to thank your sister, Ksenija, for her sacrifice and for taking care of you. She fought for your life until the very end. Thank you, Ksenija.

Today we are only putting your body in the grave, and not your soul. Your soul is not carrying any luggage on its journey. It is bodiless, shines and shimmers in the dark. Somebody once said that life is a dream, an illusion, and death is the awakening. My dear, only mother, I wish your body eternal rest and your soul a very happy, long journey.

![]()

In 2006 I’d traveled to Laos as a visiting artist, under the auspices of an art and education organization called The Quiet in the Land, founded by the curator France Morin. I didn’t have a specific piece in mind, but I happened to arrive during a Buddhist holiday, a celebration of water. All the people were gathered along the river, the priests were chanting—and all the little kids were running around with toy guns, playing war games. I was so struck by this contrast, which to me reflected the heavy history of war in that country, especially during the Vietnam War.

While I was there I visited two of the most important shamans of Laos. I also found out that the United States had dropped more bombs on Laos than on Vietnam during the Vietnam War, and that children were still being injured, crippled, and even killed by unexploded bombs. And these same injured and crippled children were playing war games with wooden guns they’d made themselves. I felt acutely how war and violence bring people to spiritual emptiness. But I also found that in monasteries monks had made bells from the big bombshells to ring for meditation, and from the small bombshells they’d made vases for flowers. This reminded me of the Dalai Lama, who said, “Only when you learn forgiveness can you stop killing. And it’s easy to forgive a friend; it’s so much harder to forgive an enemy.”

This is why I dedicated the piece to friends and enemies.

I returned to Laos in early 2008, with Paolo; my niece, Ivana, now eighteen and making her first trip to the Far East; and the great Baš Čelik film crew from Serbia. Once again, the production director Igor Kecman would work wonders, making the impossible possible amid the many restrictions imposed by the Laotian government.

My idea was a big video installation with children, called 8 Lessons on Emptiness with a Happy End. I recruited a group of very young children, ages four to ten, dressed them in military uniforms, and gave them expensive Chinese toy guns with lasers. I asked them to play war, just as they had with the wooden weapons. And anything I asked them to do they did perfectly, because they understood war so well, even at such a young age. I’ll never forget one image from the video: seven little girls lying in a bed, covered by a pink blanket, with their weapons lying next to them. The combination of the innocence of children’s sleep and violence was devastating.

To re-create the drama of warfare, performed by children, was the strongest statement I could make. The video’s lessons on emptiness were images of war—battles, negotiations, searching for landmines, carrying the wounded, executions—reenacted with kids; the happy end was a massive bonfire in which we burned all the children’s weapons in front of the whole village. The children didn’t want to burn their weapons, because it was the first time they’d had toys that weren’t made of wood. But this was my lesson to them about detachment, and the horror of war. The plastic guns burned so terribly, throwing up a cloud of thick, smelly black smoke that covered the village: it was like burning evil itself.

While we were in Laos, Riccardo Tisci sent us an enormous box containing two haute couture gowns he’d designed. He was creating a big fashion show in Paris for Givenchy, and he wanted Paolo and me to interpret the dresses for him—to alter them artistically. After the show, at the gala dinner, we would present two videos, his and mine, showing what we had done with these dresses.

We altered the gowns in very different ways. Paolo made a big cross and put his dress on it and burned it. I took mine to a waterfall and washed it to death, just scrubbed the hell out of it, like Anna Magnani scrubbing the dress in Volcano. When we flew to Paris and showed Riccardo our videos, he was very happy.

At the Givenchy party after the show, I noticed a tall redhead in a black leather dress. With her flaming hair and pale skin, she looked like she’d stepped straight out of one of the Bettie Page pinups that Paolo had been collecting since he was sixteen. “Amazing, right?” I said to him. “Amazing,” he said, nodding. Someone said she was a sexual anthropologist. Perfect, I thought. Our friend the photographer Marco Anelli was next to me, and I asked him to take a picture of her. She didn’t smile.

The next day, it was time to fly home, but Paolo said he wanted to stick around Paris for a couple of days, then go to Italy for a week before returning to New York. To recharge. We kissed. “See you then,” I said.

But when I got back to the city, something strange happened. One afternoon I was walking down the street in Soho when suddenly a feeling of overwhelming sadness washed over me. I really felt as though my heart was broken, as if all the energy had just been sucked out of me, and I had no idea how or why. I’m overworked, I thought. I really should spend more time with Paolo—I’m not giving him enough attention.

Then he came back from Milano, and everything started to get strange.

Paolo was always melancholic, but now he was sadder than I’d ever seen him. He just moped around the apartment, staring at his computer for hours at a time. Or talking on his cell phone in Italian, or texting. And every time I came into the room, he would hang up or close his computer. He started to complain—our friends annoyed him; he couldn’t find a gallery that would show his work in New York. He seemed constantly irritated by me, and whatever I did. All the signs were there, but I still didn’t know what to make of them.

To make things worse, we’d decided to renovate our place, and we were in the process of moving to a rental on Canal Street while the work was being done. We’d packed up all our stuff in boxes and put them in storage; everything was upside down.

And then Paolo, with the saddest expression on his face, told me that he felt completely in my shadow, and that he wanted to leave for a while and do his own work. In Italy.

So we made love, and then he left, leaving me to handle the renovation by myself. I stayed by myself in this place on Canal for three months, and he never called. Then, out of the blue one day, he showed up again, looked at me, and said, “I want a divorce.”

“Is it another woman?” I asked.

He shook his head. “No, no, it’s not that,” he said.

“Then what?”

“I have to find myself,” Paolo told me. “And I can’t find myself while I’m with you. I’ve lost myself while I’ve been with you.”

I took this in for a minute. There was a strange little echo in my mind. Then I said, “You know what? I can’t accept this. I want to wait one year. I’ll wait for you for one year.”

In the meantime, I told him, I would sell our vacation house in Stromboli and give him half the proceeds. We had this beautiful place on that beautiful island north of Sicily; when we married I’d given him half the house as my present. I would wind up selling it for a million euro and giving Paolo half the money to help him find himself, not knowing what he was really spending it on.

But then I knew nothing. And I still loved him; I couldn’t help myself. “Come here, baby,” I said. We lay down on the bed together, fully dressed. And this was the worst part. “I can’t touch you,” he told me. Then he got up and left again.

The strangest thing. As everything was falling apart with Paolo, but before I had any idea he was going to leave me, I made this image of myself carrying a skeleton into the unknown:

Carrying the Skeleton, color chromogenic print, New York, 2008

He came back three times over the next few months, but he always left again. Each time was awful. Once, we started to make love and then he just stopped. “I can’t do it,” he said.

I looked into his eyes. “Do you have another woman?” I asked.

He looked into my eyes and told me he didn’t.

I believed him. Maybe I was a fool. But our intimacy was such that I trusted him blindly. He knew how much Ulay had lied to me, and he always said, “I will never hurt you like that.” He said it so many times—and he did worse.

![]()

That July, Alex Poots, the director of the Manchester International Festival, and Hans-Ulrich Obrist, the artistic director of the Serpentine Galleries in London, invited me to curate a performance event at Manchester’s Whitworth Art Gallery. The event was to be called Marina Abramović Choices. The idea was to combine long-durational performances, over seventeen days and four hours a day, by fourteen international artists—and to prepare the public, in a completely new way, to view these works. I invited some of my former students and other artists I’d never worked with before: Ivan Civic, Nikhil Chopra, Amanda Coogan, Marie Cool and Fabio Balducci, Yingmei Duan, Eunhye Hwang, Jamie Isenstein, Terence Koh, Alastair MacLennan, Kira O’Reilly, Melati Suryodarmo, Nico Vascellari, and Jordan Wolfson.

Alex and I went to meet Maria Balshaw, the director of the Whitworth. She asked how much space I needed. And I asked her, “Do you want to make something regular and ordinary, or something unique and extraordinary?” She said that of course she wanted to do something unique.

“Then empty the whole museum,” I said. “We’ll take the whole space.”

She looked at me with amazement—no one had ever asked her this before. To empty the whole museum would take three months, she said, and asked me to give her some time to think about it. The next day she said, “Yes, let’s do it.”

To enter the museum, the public had to sign a certificate promising they would stay four hours without leaving. They had to put on white lab coats, so they could feel they were making a transition from viewers to experimenters. For the first hour they were there, I would give them simple exercises: slow walking, deep breathing, looking into each other’s eyes. After I had conditioned them, I would then lead them to the rest of the museum to see the long-durational performance work.

This was the first attempt at a format that would later form the basis of my institute and my Method.

![]()

In the middle of all of this, Klaus Biesenbach and I had begun planning the biggest show of my life, a career retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art. Klaus was very blunt about what he wanted. He was much less interested in my non-performance work—the transitory objects with crystals—than in my performance pieces. He told me that when he was an art-loving kid in Germany, invitations to exhibitions used to come on postcards. And the postcards that always excited him the most were the ones that said on the bottom, “Der Kunstler ist anwesend”—the artist is present. Knowing the artist would be right there in the gallery or the museum meant so much more than just thinking about going to look at some paintings or sculptures.

Klaus said, “Marina, every exhibition needs a kind of rule of the game. Why don’t we have one very strict rule: you have to be present in every single work, either in a video, or a photo, or a restaging of one of your performances.”

At first I didn’t like the idea. So much of my work would have to fall out, I complained. But Klaus insisted. He had become very strong-willed since our first meeting, almost twenty years earlier! But he was also so smart, and he had accomplished a great deal. I trusted him. And I began to warm to his concept.

The Artist Is Present.

I had an idea. On the upper floors there would be continuous re-performances of my pieces, but in the atrium space, I would do a major new performance, with the same title, where I would be present for three months. It seemed like an important opportunity to show a large audience the potential of performance: this transformative power that other arts don’t have.

I thought again of the Rilke line I’d loved as a girl: “O Earth: invisible! / What, if not transformation, is your urgent command?” And of the great Taiwanese-American artist Tehching Hsieh—for me, always a true master of performance art, and one who truly represents transformation. Tehching has made five performances in his life, each of them lasting for one year. He followed this with a thirteen-year plan, in which he made art without showing it. If you ask him what he’s doing now, he will say he is doing life. And this, for me, is the ultimate proof of his mastery.

With Tehching Hsieh

The new piece took shape in my mind. We were talking about five decades of my career as an artist….In my mind’s eye I saw shelves, similar to The House with the Ocean View, only in chronological levels—up and down rather than straight across. Each shelf would represent a decade of my career, and I would move from level to level throughout the performance. The idea became very complex. I even designed chairs for the audience, something like chaise longues, with binoculars attached: people could recline comfortably in the atrium, I thought, and watch my eyes and the pores of my skin if they chose.

It was all very exciting—and complicated. There were structural issues with fastening the shelves to the atrium wall, there were security and liability questions. Klaus and I began planning….

All this busyness, and then Paolo left.

I was going mad. I was crying in taxis. I was crying in supermarkets. Walking down the street, I would just burst into tears in the middle of the sidewalk. I talked to our friends and his family about nothing else—I got sick and tired of listening to myself talking about it, and I knew all my friends were sick and tired of listening to me. I couldn’t eat, I couldn’t sleep. And the hell of it was that I just couldn’t understand why he had gone away.

I was a total wreck. But what could I do? I went on.

One day that summer, Klaus and I were visiting the Dia Art Foundation, a wonderful modern-art museum in upstate New York, and we were looking at the wall drawings of Sol LeWitt, who had just died the year before. These are big, beautifully stark graphite grids, extraordinarily simple—which means that their conception was so difficult. And as I stared at these drawings, I began to weep.

It was everything. Paolo, the gorgeous simplicity of these grids, LeWitt’s death…I really wasn’t sure. It didn’t even matter. Klaus took me by the hand, and we walked on until we came to a Michael Heizer piece: a rectangular hole in the floor with a smaller rectangular opening inside, almost like a conversation pit. We sat on the edge, and Klaus talked to me. He spoke softly, but—this is his way—he was very direct.

“Marina,” he said, “I know you. And I’m worried about you. This is the same tragedy in your life, all over again. You were with Ulay for twelve years; you were with Paolo for twelve years. And each time, the umbilical cord gets cut, and boom—you’re devastated.”

I nodded.

“This Michael Heizer piece is reminding me of a very famous image of you and Ulay performing Nightsea Crossing in Japan,” Klaus said. “Remember? There was a square hole like this in the floor, and the table was in the hole, and you and Ulay sat across from each other.

“Marina, why don’t you face the reality of who you are now?” he said. “Your love life is gone. But you have a relationship with your audience, with your work. Your work is the most important thing in your life. Why don’t you just do in the MoMA atrium what you did in Japan with Ulay—except that instead of Ulay sitting across the table from you, it is the public? Now you’re alone: the public completes the work.”

I sat up very straight, thinking about it. The Artist Is Present was taking on a whole new meaning. But then Klaus was shaking his head. “Or maybe not,” he said. “We’re talking about three months, all day, every day. I don’t know. I don’t know if it would be good for you, physically or psychologically. Let’s go back to the shelves.”

But the more I thought about the shelves, the more complicated the whole idea seemed. Too complicated. I thought about Sol LeWitt’s beautiful simplicity. The whole way home, I kept bringing up the table idea—and Klaus kept shooting it down. “No, no, no,” he said. “I don’t want to be responsible for you doing that kind of damage to yourself, physical and psychological damage.”

“I think I can do it,” I said.

“No, no—I won’t hear it. Let’s talk about it another day.”

I called him back the next day. “I want to do it,” I said.

“Absolutely not,” Klaus said. But by then I realized we were playing a game, and that it was a game both of us had understood from the start.

![]()

Soon afterward I was at dinner at a friend’s place, talking to a few people I’d just met about my plans for The Artist Is Present. One of them was Jeff Dupre, who had a film company called Show of Force. He was so enthusiastic about my plans for the retrospective that he said, “Why don’t we make a film about your preparations?” A few days later Jeff introduced me to a young filmmaker, Matthew Akers. Matthew knew nothing about performance art—in fact he seemed skeptical about it—but was very interested in me and the project anyway.

It happened that I was just beginning a workshop, called Cleaning the House, with the thirty-six performance artists who were going to re-perform my pieces in MoMA. And though there hadn’t been enough time yet to find the money for the movie, Matthew was so eager to start that he decided to begin filming immediately. He filmed the workshop, and then we decided that he and his crew would follow me for the entire next year to record the preparations for The Artist Is Present.

With Matthew Akers at the Sundance Film Festival, 2012

For the next year, I lived my life with a microphone taped to me and a camera crew documenting my every movement. I gave Matthew the key to my house so the crew could come anytime, even six in the morning. Sometimes I would wake up to the sight of a cameraperson standing at the foot of my bed. There were times I wanted to kill Matthew and his crew with my own hands. It was very hard to have any privacy, but this was something I felt I needed to do: I saw this as my only chance to show the general public, who didn’t even know what performance art was, how serious it was, and how profound an effect it can have.

And I had no idea at all what tack Matthew was going to take in his film—I knew there was even a chance the piece might ridicule me. It didn’t matter. I believed so strongly in what I was doing that I felt he might come to believe in it, too. And in the end, he did.

I went into training. Just to be clear, we were talking about me sitting in a chair in the atrium of the Museum of Modern Art for eight hours a day, every day (and ten hours on Fridays) for three months, continuously and without moving—no food or drink, no bathroom breaks, no getting up to stretch my legs and shake my arms out. The strain on my body (and mind) would be huge: there was no anticipating exactly how huge.

My preparation. Dr. Linda Lancaster, a naturopathic physician and homeopath, created a nutritional plan for me. This was really like a NASA program. Not eating or going to the bathroom was a big deal. The stomach produces acids around lunchtime—the body learns through repetition that it is going to be fed, so if you don’t have lunch, your blood sugar level goes down, and you can have headaches and get sick. So a year ahead of the March 2010 opening, I had to start learning to have no lunch at all, and to eat breakfast very early in the morning and a small, protein-rich meal in the evening. I had to learn to drink water only by night, never by day, because peeing during the day would not be an option. Just in case, I had a trapdoor built into the seat of my chair that would allow me to urinate while sitting there. After the second day of my performance I knew I would never need it—I put a cushion on top of it. There was some speculation during the performance about whether I was wearing an adult diaper. I was not. There was no need. I am the daughter of partisans. I had trained my body.

My heart was another question—for the heart, there is no NASA training. I missed Paolo so desperately. I wanted him back, shamelessly, more than anything.

Of course it wasn’t just him. It’s one thing to be forty when you split with somebody, as I was when my relationship with Ulay fell apart. It’s another thing to be in your sixties—you face loneliness in a completely different way. This whole thing was a mix of getting old and feeling unwanted. I felt so isolated, and the pain was just too much to bear. I began to see a psychiatrist. She prescribed antidepressants, which I never took.

I went through all of 2009 without seeing Paolo. As we agreed, we would wait until the first of June to decide if we were to stay together or not. Midway through the year, I found out the truth from a friend in Milan: there was someone else, and it was that woman, the one we’d met at the Givenchy show, the sexual anthropologist. They’d been together since the day after the event, when Paolo had decided to stay in Paris. It took me all too long to realize that he’d left me for her in precisely the same way he’d left Maura for me. That he had played me just the way he’d played her. With a dead feeling in the center of my heart, I filed for divorce. It became final that summer. One night soon afterward I went to dinner with the artist Marco Brambilla, whom I’d recently met and who has since become a very good friend. We bonded that night over our stories of heartbreak. As we commiserated, it was clear he was really trying to cheer me up, and even though I don’t drink, I had a big glass of vodka to wash away the pain. I needed it.

Marco Brambilla and me in Venice, 2015

Knowing the bad condition I was in, Riccardo Tisci invited me to go on holiday with him and his boyfriend to the island of Santorini, in the Aegean Sea. When I arrived at Athens harbor to catch the ferry, Riccardo was alone. “What happened?” I asked. “He just left me,” Riccardo said.

It was the saddest holiday on earth—the two of us just cried and cried. This was the moment Riccardo and I really became close friends. But after he went back to Paris to work, I felt I still needed to heal some more. And so, at the invitation of Nicholas Logsdail, I went to the island of Lamu, in the Indian Ocean off the coast of Kenya.

Lamu was an old Swahili settlement with no roads, but a lot of donkeys everywhere. The atmosphere was kind of post-Hemingway. The sheriff of the island was named Banana; the barista at the café was called Satan. Nicholas’s cook was named Robinson. I asked him if his last name was Crusoe, and he said yes, of course. Another artist, Christian Jankowski, was visiting Nicholas, along with his girlfriend. They both tried to cheer me up with jokes; in return I told them the saddest Balkan jokes I could think of. Someday, Christian and I decided, we would make a joke book together.

Then, one day, I decided to go back to work.

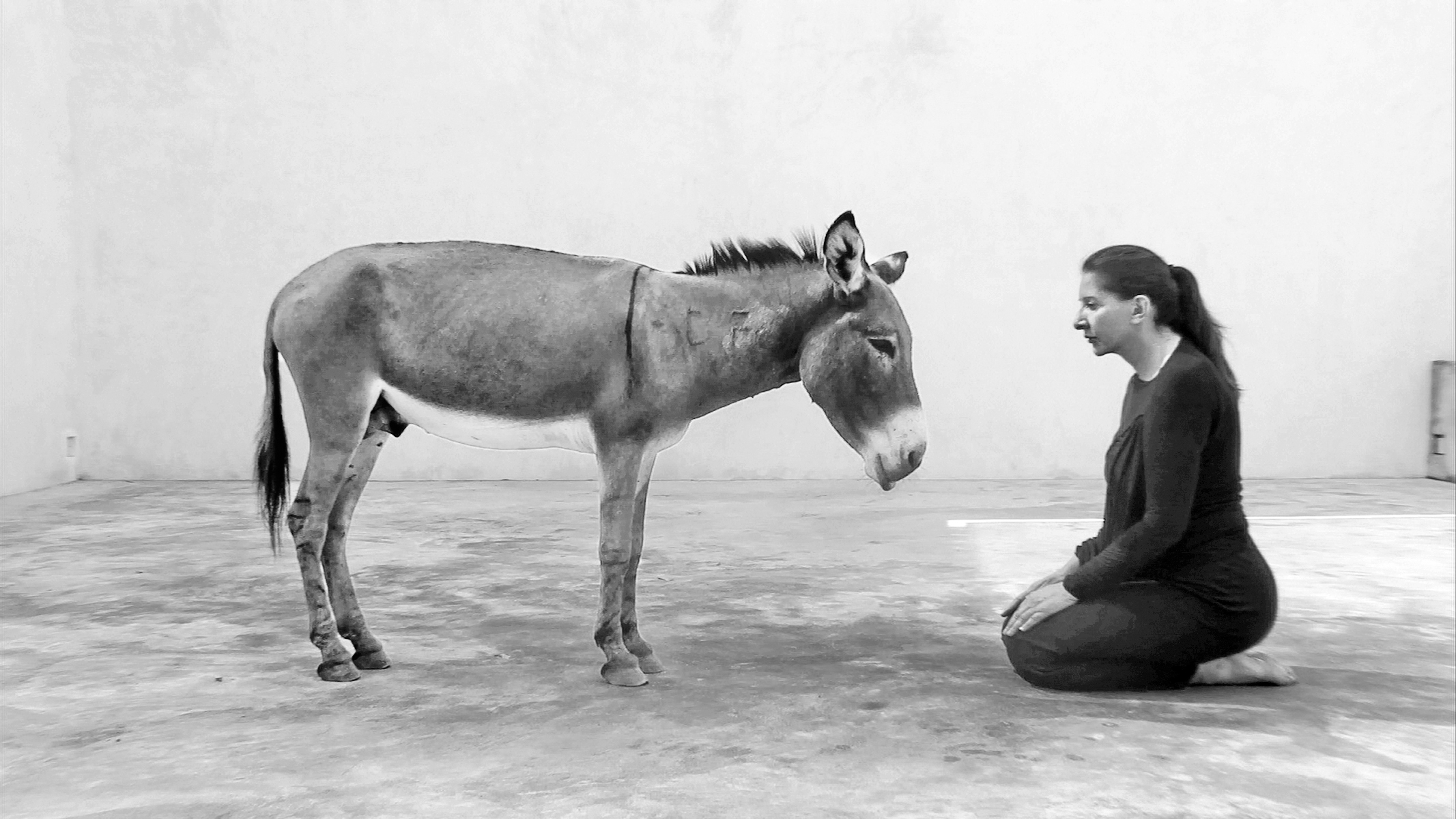

The donkeys of the island impressed me. They were the most static animals I’d ever seen—they could stand in the burning sun for hours, hardly moving. I took one donkey into the backyard of Nicholas’s house and made a video piece called Confession. In it, I first tried to mesmerize the animal with my gaze as he stood opposite me, virtually frozen and with a deceptively sympathetic look in his eyes. Then I began to confess to the donkey all the flaws and mistakes of my whole life, starting from my childhood and extending to that day. After about one hour, the donkey decided to walk away, and that was it. I felt a little bit better.

Confession (performance for video, 60 minutes), 2010

That fall I went with Marco Anelli to Gijón, Spain, to make a new work, a set of videos and photos called The Kitchen. The piece was set in an actual kitchen, an extraordinary architectural space in an abandoned convent of Carthusian nuns who had fed many thousands of orphans while the convent was active. Although the work was born as an homage to Saint Teresa of Ávila—who in her writings tells of an experience of mystic levitation in her kitchen—it became an autobiographical piece, a meditation on my childhood, when the kitchen of my grandmother was the center of my world: the place where all the stories were told, all the advice about my life was given, all the future-telling through cups of black coffee took place.

I was fascinated by the stories of Saint Teresa’s levitation, which many witnesses confirmed. One day (one of the accounts said), after she had been levitating for a long time in the church, she got hungry and decided to go home and make herself some soup. She returned to her kitchen and started cooking, but suddenly, unable to control the divine force, began to levitate again. And so, in the middle of cooking, she hovered above the pot of boiling soup, powerless to descend and eat, hungry and angry at once. I loved the idea that she could be angry with the very powers that made her saintly.

The Kitchen I, color fine art pigment print from the series The Kitchen, Homage to Saint Teresa, 2009

I returned to New York, but I couldn’t face Christmas and New Year’s alone, and I couldn’t stand the thought of being around happy couples during the holidays. So I went traveling again, this time to southern India for a month of panchakarma therapy. Doboom Tulku and my close friend Serge Le Borgne accompanied me, as did Matthew Akers and his film crew.

Panchakarma is a form of Ayurvedic healing, a very old Sanskrit system of medicine that involves a complete detox for twenty-one days, daily massages, and meditation. Every morning you drink liquid ghee to lubricate the internal cells of your body. I went to this place for a month, and I felt so clean. I felt as though all the germs had left my body, including Paolo. Then a funny thing happened.

It took me almost thirty-six hours to get home from India: a long car ride to catch a local plane; the local plane to get another plane; changing planes in London; waiting in waiting rooms; reading magazines; nodding off. Finally I got back to New York, and the next day—I’d gone to the movies—I got as sick as a dog. Vomiting, high fever; terrible. All while Matthew Akers and his faithful crew continued to film me. I realized I still had a hole in my heart from Paolo. But in the middle of it all I remembered something my grandmother had said: “Whatever starts bad always finishes good.” So I thought, Okay, maybe this is the way it has to be—going from total health and cleansing into complete sickness. Then one morning I was better, and then it was time for The Artist Is Present.