Noah’s mother had never been the type of woman to do unexpected things, but this had all changed a few months earlier after their springtime holiday to Auntie Joan’s was cancelled. They had gone there every Easter for as long as Noah could remember and he always looked forward to the trip, not just because they lived by the sea and Noah could spend hours splashing about in the water and making castles on the beach, but because his cousin Mark was his best friend, even though they only saw each other a few times a year. (The coast, where Auntie Joan lived, was a long way from the forest, where the Barleywater family lived.)

Everyone said that Mark was the opposite of Noah. He was tall for his age, and his parents told him they were going to put a brick on his head to stop him growing because he wasn’t able to keep any clothes for more than a few months before he grew out of them. And he had a mop of blond hair, where Noah’s was black. And he had blue eyes to Noah’s green. And he was a bit of a star at football and rugby, two games that Noah liked to play but wasn’t very good at. For some reason he always got confused whenever they played them at school – football on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays; rugby on Tuesdays and Thursdays – and picked up the football and threw it sideways to the other boys on his team, or took aim at the rugby ball and kicked it into the back of the net, shouting ‘Goooooaaallll!’ in a loud voice before running around the pitch with his shirt pulled over his head until he fell over. If it wasn’t for the fact that the other boys in his class generally liked Noah, then there was a good chance they would have kicked him in after it.

‘A slight change of plan,’ his mother said one evening when the family was sitting down to dinner. ‘Regarding Auntie Joan’s, I mean.’

‘We’re still going, aren’t we?’ asked Noah quickly, looking up from his plate of fish pie, which he’d been moving around with a fork in the hope of finding something edible in the squishy mess that sat before him. (His mother was many things, but a good cook was not one of them.)

‘Yes, yes, we’re still going,’ said his mum, looking around the table for salt and pepper to mask the taste rather than meeting his eye. ‘Well, when I say we’re still going, I mean we will be going. At some point in the future, that is. Just not next week like we planned.’

‘Why not?’ he asked, his eyes opening wide in surprise.

‘A different week,’ said his father quickly. ‘We can go in the summer, all being well.’

‘But it’s all arranged,’ said Noah, looking from one to the other in dismay. ‘I wrote to Mark last week and we decided that on the first afternoon we’d go in search of crabs and—’

‘The last time you went looking for crabs with Mark, you filled a bucket with them, and when one of them jumped out onto your arm, you dropped the lot on the stone floor of Auntie Joan’s kitchen and they all ran away.’ said his mother. ‘Except for one unfortunate crab whose shell broke as it hit the floor. If anything, I imagine the crab population will be pleased to hear that you won’t be visiting this Easter.’

‘Yes, but I was only seven then,’ explained Noah. ‘Nobody knows how to behave when they’re seven. But I’m eight now. I would treat the crabs with a lot more respect.’

‘You mean you’d keep their shells intact before you dropped them, still breathing, in a pot of boiling water?’ asked his father, who described himself as a bleeding-heart liberal and proud of it.

‘I would,’ agreed Noah. ‘So can we go?’

‘No,’ said his mother.

‘But why not?’

‘Because we can’t.’

‘Why can’t we?’

‘But why are you saying so?’

‘Because it’s not possible right now.’

‘But why isn’t it possible right now?’

‘Because it isn’t!’

‘That’s not an answer!’

‘Well, it’s the only answer you’re getting, Noah Barleywater,’ she snapped, and he knew that was the end of the matter, because his mother only used his full name when she had made up her mind on something and there was no turning back. ‘Now eat your fish pie before it gets cold.’

‘I hate fish pie,’ grumbled Noah, who rather liked it actually when it was cooked right. (As in, by someone who knew how to cook.)

‘No you don’t,’ said his mother. ‘You always order fish pie when we go out for dinner.’

‘I don’t hate real fish pie,’ agreed Noah, moving the pale pink and white slop around on his plate, some of the fish pieces looking so raw and inedible that a skilled veterinarian might have brought them back to life. ‘But this, Mother … this – I mean, really.’

Noah’s mum sighed. She knew that Noah only called her ‘Mother’ when he was absolutely certain of something and there was no convincing him otherwise. ‘What’s wrong with it?’ she asked after a moment.

‘It tastes like sick,’ he said with a shrug.

‘Noah!’ snapped his father, stopping his own fork from pushing the food around the plate for a moment to stare at his son. ‘That’s a terrible thing to say.’

‘No, he’s right,’ said his mother with a sigh, pushing her plate away. ‘I can’t cook for toffee, can I?’

‘You make quite good tomato soup,’ said Noah, willing to give her that.

‘That’s true,’ she said. ‘I can open a can with the best of them. But my fish pie isn’t up to scratch.’

‘To be fair,’ said Noah’s father, ‘it does look like something the dog would turn up his nose at. If we had a dog, that is.’

‘Let’s go out for dinner then,’ said his mother, standing up and clearing the plates away. ‘And you can order whatever you want.’

Noah smiled, the disappointment of the non-holiday forgotten for a moment, and jumped down from his seat, but just as he did so, his mother dropped the handful of plates she was holding, and all three fell to the ground, sending potatoes, prawns, cod, peas and all manner of squishy ingredients all over the floor. Noah jumped, expecting her to say that she was a terrible butterfingers, always dropping things, but instead she was leaning against the sideboard, one hand pressed to the small of her back, and was groaning quietly, a strange and disturbing sound, a heartbreaking cry that he had never heard her make before. Noah’s father immediately jumped up and ran to her, and Noah stepped forward too, but there was no way over the fallen fish pie except to take a giant leap and he wasn’t sure he could make it without taking a step back first.

‘Go up to your room, Noah,’ said his father before he could do this though.

‘What’s the matter with Mum?’ he asked nervously.

‘Go up to your room!’ his father repeated, raising his voice now, and he sounded so serious that Noah immediately did as he was told, trying not to think about what was really going on downstairs.

And that, for the time being, was the end of that.

But then, two weeks later, on the day they should have been going to Auntie Joan’s if the plan hadn’t been changed, he was standing in front of his bedroom mirror measuring his muscles when his mother came marching in. She’d been sick in bed for a few days before that, but seemed to be better now and had been away all the previous day on what she described as a secret mission that he would learn about soon. ‘There you are!’ she said, smiling at him. ‘How do you fancy a day out?’

‘Love to!’ replied Noah, putting down the measuring tape and making a note in his book of his current measurements. ‘Where to this time? Back to the pinball café?’

‘No, I have a much better plan that that,’ she said. ‘Since we can’t go to the seaside, I thought we should bring the seaside to us. What do you think of that?’

Noah sighed and shook his head. ‘We live on the edge of a forest, Mother,’ he said. ‘I don’t think we’ll find any beaches around here.’

‘If you think I’d let a little thing like that stand in my way, then you don’t know me at all,’ she said, sticking out her tongue at him and making a face. ‘You do realize that I’m the most amazing mother in the world, don’t you?’ Noah nodded but said nothing. ‘All right then,’ she said, clapping her hands together twice, and quickly, like someone in a television programme about to cast a spell. ‘Grab your swimming trunks and a towel. I’ll meet you downstairs in five minutes.’

Noah did as he was told, wondering what on earth could possibly have got into her. This was the second time she had taken him away for the day on an unexpected treat. The first time, the pinball time, had been the most terrific fun, and if that was anything to go by, then this would be even better. She never used to do things like this, but now, out of the blue, they were all the rage. Although he couldn’t imagine how she could possibly bring the seaside to the forest. His mother was many things, but magic she was not.

‘Where are we going?’ he asked when they were sitting in the car, driving along with the top down for once. (In the past, Mrs Barleywater had said she didn’t like to do that in case she got a cold, but she didn’t seem to be worrying about that any more, and seemed happy to enjoy the fresh summer breeze. You only live once, she’d said as she pulled it down.)

‘I told you,’ she said. ‘The seaside.’

‘Yes, but in real life,’ he asked.

‘Noah Barleywater,’ she replied, turning to look at him for a moment before turning back to watch the road, ‘I hope you’re not suggesting that I would let you down. You told me that you loved going to the beach.’

‘Yes,’ he said, ‘but that’s hundreds of miles away. We’re not driving hundreds of miles, are we?’

‘Oh no,’ she said, shaking her head. ‘No, I wouldn’t have the energy for that. No, we should be there in about fifteen minutes.’

And sure enough, fifteen minutes later, having driven away from the forest and in the direction of the nearby city, they arrived at a hotel that Noah had never seen before and pulled into the car park. ‘Don’t say anything,’ said Noah’s mother, noticing the sceptical look on her son’s face. ‘Just trust me.’

They went inside, and Mrs Barleywater waved at one of the receptionists, who immediately came out from behind her desk wearing a broad smile on her face and handed her a key.

‘Thanks, Julie,’ said Noah’s mum, winking at her, and Noah frowned in surprise, for he was sure he knew all his mother’s friends and this Julie was a new one on him. He followed her as she walked on, however, only turning round for a moment to glance back at the receptionist, who was now standing with one of her friends, watching them walk away. She seemed to be shaking her head as if she was very sad about something, and she spoke to her friend, whose mouth fell open as if she’d just been told a terrible secret.

‘Just down here,’ said Noah’s mother, holding his hand as they walked along the corridor. ‘And through here. Do you want to press the button?’

Noah sighed and shook his head. ‘You do remember I’m eight, don’t you,’ he asked, for when he was younger he always wanted to be the one to press buttons in lifts, ‘not seven? Still, it needs to be pressed, I suppose.’

‘B,’ said his mother, and he pressed the button marked ‘B’, the doors closed and the lift slowly descended with a great many creaks and whistles.

‘Where are we going?’ he asked after a moment.

‘Somewhere good,’ she said.

When the doors opened again, they walked along another corridor, and Mrs Barleywater opened a door to an empty changing room. ‘Run in there and put your trunks on,’ she said. ‘I’ll change into mine next door. Quick sticks, now! Meet you out here in five minutes flat.’

Noah nodded, did as he was told, and five minutes later the pair of them were walking down another corridor until finally his mother stopped outside a door and turned round, smiling at him. ‘I’m sorry we couldn’t go to the beach this year,’ she said. ‘But I didn’t want you to miss out just because of me.’

‘What do you mean just because of you?’ he asked, but instead of answering she simply unlocked the door with the key she had been given and they stepped through into the hotel’s swimming pool area. Noah had been in pools before but never one like this. For one thing, there was no one else around, which was a big surprise in a hotel like this. Usually the pool was filled with middle-aged men splashing around in the water like whales as they powered their way through their lengths, or terrified-looking children bouncing nervously in the shallow end in case they lost their footing and the ground went from beneath them. But instead there was just the two of them, Noah and his mum.

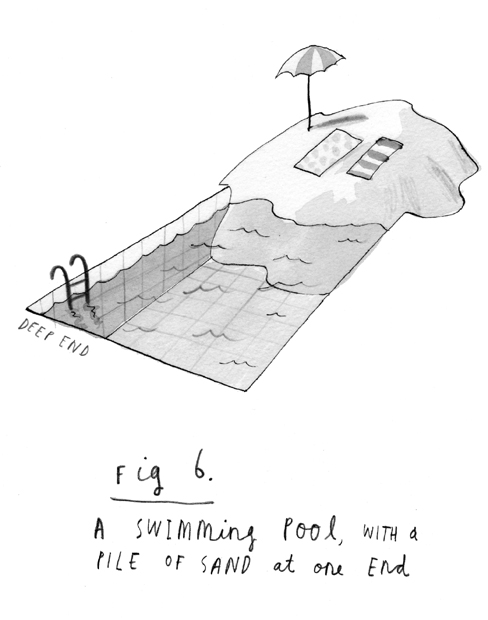

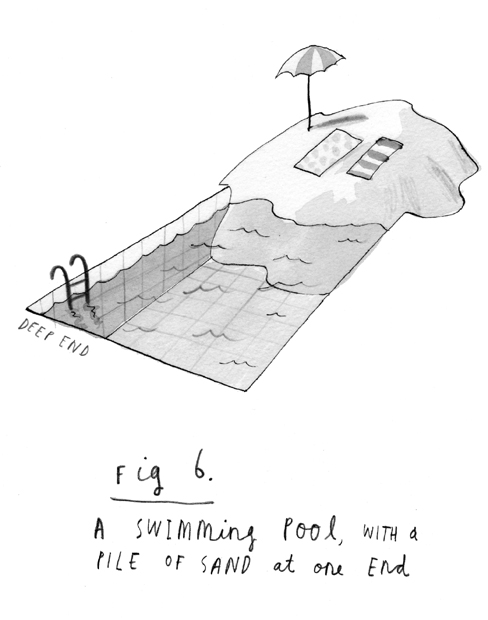

But if he thought this was unusual, it was nothing compared to the way the swimming pool looked. Half a dozen small piles of sand had been brought in and built into dunes, and although it looked nothing like a real beach, it was probably the closest thing you could find at a swimming pool. Noah’s mouth fell open in surprise and he looked up at his mother in wonder.

‘All right, it’s not quite the real thing,’ she admitted. ‘But we have the place to ourselves and we can pretend we’re at the beach, can’t we? One more beach holiday together. Let’s make the best of it, shall we?’

‘Well, it’s not just one more,’ he replied. ‘I mean, we can always go to Auntie Joan’s next Easter, can’t we? Or even later in the summer?’

Mrs Barleywater opened her mouth to reply but it seemed to take her an awful long time to find the words. She swallowed and looked away, and then leaned down and hugged Noah to her so tight that he thought she had gone mad.

‘What’s the matter?’ he asked nervously, pulling away from her. ‘Why are you acting so strange?’

‘Me? Strange?’ she said, clearing her throat and turning away from him. ‘I don’t know what you’re talking about. Now, how about we take a swim?’ she asked, walking over to the side of the pool. ‘Race you to the other side.’

And with that, the two of them dived into the cold water and reached the other side almost neck and neck but it was finally agreed that Noah’s mum had just edged it, although it was the only race she won for the rest of the afternoon, for Noah was a very strong swimmer and his mum seemed to get very tired quite quickly. Sandcastles were built, more swimming took place, and at just the right moment a picnic of sandwiches and fizzy drinks was served by a young man from the hotel staff, who seemed entirely unimpressed by what was taking place there.

‘Well?’ asked Noah’s mother, throwing a few grains of the sand in his sandwich so it would taste even more like they were at the beach. ‘Did you have a good time?’

Noah nodded quickly and looked at his mum, smiling widely. He wondered whether maybe she had some sort of allergic reaction to the chlorine in the water though, for her eyes seemed to be very red around the edges, as if she had been crying while she was in the pool. He was going to tell her that she should wear a pair of goggles in future, but his mouth was so full of egg sandwich at the time that he couldn’t get the words out without spitting it all over her, and a moment later, when it wasn’t, he’d already forgotten.

‘We have to make the most of days like this, Noah,’ she said quietly then, trying to pull him close to her again, but this time he pulled away because her swimsuit was too wet, and instead he jumped back into the water for another swim. He liked this new side of his mother, these unexpected days out. It was almost as if she was a different person.