The Civil Rights Movement in the West,

During World War II, nearly half a million African Americans migrated to the West. They joined 1.3 million other black westerners in defense industries or the military as part of the double victory campaign to defeat the Axis and racial discrimination. When half the double V campaign ended with the Allied victory in 1945, the other half, the struggle for civil rights, continued almost without interruption. The West offers a particular vantage point for reexamining the civil rights era. Historians of the period have focused on national legislation, such as the Civil Rights Act of 1964, or on efforts in the South to confront Jim Crow. Civil rights activities in the West suggest a third alternative. Direct-action protests, though often inspired by southern campaigns in Birmingham or Selma, had different goals in the West. Westerners confronted job discrimination, housing bias, and de facto school segregation. Thus the civil rights movement was national in scope, its western version integral to the effort to achieve a full, final democratization of the United States.1

Western civil rights activity began long before World War II. Nineteenth-century black parents fought school segregation in California, Colorado, Kansas, and Montana. Yet by the 1950s an urgency grew, born of the World War II promise of democracy, a rapidly growing African American population, and the flowering of postwar liberalism, when white politicians embraced civil rights issues. Moreover, many Westerners had been sensitized to twentieth-century racial injustice through the recent Japanese internment, the zoot suit riot, and the black-white confrontations in shipyards and military bases. The 1950s in fact marked an optimism about the region’s racial future. William Mahoney, a white civil rights activist in Phoenix, said as much in 1951: “The die is . . . cast in the South or in an old city like New York or Chicago, but we here [in Phoenix] are present for creation. We’re making a society where the die isn’t cast. It can be for good or ill.” The African American minister Roy Nichols, pastor of racially integrated Downs Memorial Methodist Church in Berkeley, shared this optimism during his 1959 campaign for a city council seat: “What other race in the twentieth century is going to have such a great experience?”2

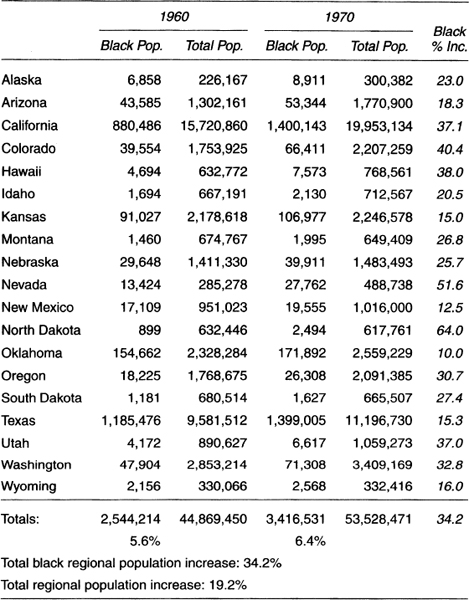

Western Black Population Growth, 1960–70

Source: U.S. Bureau of the Census, Census of Population, 1960, vol. 1, Characteristics of the Population, parts 4–49 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1963), table 15; 1970 Census of the Population, vol. 1, Characteristics of the Population, parts 4–49 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1973), table 17.

Civil rights activity in the West took two distinct forms. The legal campaign used the courts to desegregate public schools, which many black westerners came to view as central to economic and political advancement. But black westerners also engaged in direct-action protests: demonstrations, sit-ins, boycotts, and other civil disobedience activities to eliminate discrimination. The legal effort reached its apogee with the 1954. Supreme Court decision Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka. However, direct action from Seattle to Austin preceded and followed Brown.

After 1965 the black power movement challenged both the tactics and goals of the civil rights movement. The Watts uprising of 1965 illustrated to the region and the nation the inability of nonviolent protest alone to address the concerns of millions of urban blacks trapped by inner-city poverty. Watts reminded the nation that while the ghettos of the West seldom resembled Harlem’s brownstone tenements or Chicago’s high-rise public housing, they shared a foundation of poverty, alienation, and anger. One year after Watts, western African American communities in Oakland and Los Angeles produced the Black Panther party and US (United Slaves), which formulated the two distinct brands of black nationalism, revolutionary and cultural, that eventually swept through African American communities throughout the nation.

Brown v. Board of Education is often called the beginning of the modern civil rights movement. Yet Phoenix blacks won a major legal victory over de jure segregation one year before the Topeka case. Encouraged by successful legal attacks on Mexican American school segregation in California and Arizona, state Representative Hayzel Daniels in 1951 introduced a bill to give local school districts authority to desegregate their school voluntarily. The bill passed, and Tucson and other Arizona communities quickly desegregated their schools. However, the Phoenix electorate voted two to one to maintain separate schools. Daniels and Stewart Udall in June 1952 filed a lawsuit on behalf of plaintiffs Robert B. Phillips, Jr., Tolly Williams, and David Clark, Jr., who had been refused admission to Phoenix Union High School. (One of the principal financial supporters of the suit was Phoenix City Council member Barry Goldwater, who contributed four hundred dollars.) The case came before Maricopa County Court Superior Court Judge Frederic C. Struckmeyer, Jr., who ruled that Arizona’s segregation laws were invalid, adding, “A half century of intolerance is enough.” Soon afterward Daniels filed suit against the Wilson Elementary School District in Phoenix before County Court Judge Charles E. Bernstein, who ruled that segregated elementary schools were unconstitutional.3

As Struckmeyer and Bernstein rendered their decisions, the Brown case moved through the courts. In 1951 a group of African American parents, supported by the local NAACP, sued Topeka’s Board of Education, claiming segregated schools symbolized the second-class citizenship of black Topeka. By 1951 slightly more than a hundred thousand people, including seven thousand African Americans, lived in the Kansas capital. Few African Americans, however, shared in Topeka’s prosperity. Approximately one hundred black professionals worked as teachers, ministers, doctors, and lawyers. Nearly all other local blacks were janitors, maids, porters, laundresses, cooks, and charwomen. “You’d look up and down Kansas Avenue [the city’s main thoroughfare] early in the morning,” recalled Charles Scott, one of three black attorneys in the city, “and all you could see were blacks washing windows. . . . There was no chance . . . to become a bank teller, store clerk or brick mason. . . . A lot of hopes got dashed.4

Segregated schools anchored this Kansas apartheid. Topeka had no all-black neighborhoods. Nonetheless the city maintained eighteen elementary schools for white pupils and four for blacks. Topeka High School had always been integrated, and the city’s junior high schools had been desegregated after a 1941 lawsuit, Graham v. Board of Education of Topeka. Yet school administrators presided over segregation in an integrated setting. Topeka High had separate athletic teams, cheerleaders, and pep squads. Black students, excluded from the “regular” student government, had a separate advisory council and attended a separate school assembly. Black and white school administrators maintained social segregation, searching the cafeteria, for example, to detect interracial tables.5

Thirteen parent plaintiffs representing their twenty children participated in the lawsuit. The Reverend Oliver L. Brown headed the list of plaintiffs, suing on behalf of his daughter Linda. His role in the lawsuit was accidental. The thirty-two-year-old Brown, a welder for the Santa Fe Railroad and assistant minister at the St. John African Methodist Episcopal Church, was not a member of the NAACP and had no history of political activism. He was, however, one of only two males among the thirteen parents and a respected minister in the African American community. The NAACP assumed his name as lead plaintiff would lend credibility to the case. Some contemporaries remember Brown as “a good citizen . . . [but] not a fighter.” Yet the NAACP viewed his timidity as an asset. Here was an ordinary man rather than a “militant” who “was no longer willing to accept second-class citizenship.”6

In September 1950 African American elementary schoolchildren in Brown’s neighborhood, including his daughter, were expected to travel one mile to attend the all-black Monroe Elementary School. White neighborhood children traveled only four blocks to the all-white Sumner Elementary School. NAACP officials directed Brown and the other parents to walk their children to the nearest white school on the day of enrollment. Oliver and Linda Brown and the others walked to Sumner and, as expected, were turned away by the principal, setting the conditions for the lawsuit.7

Brown v. Board of Education was argued for five weeks beginning on June 25, 1951, before a threejudge federal panel headed by Walter Huxman and including Arthur J. Mellott and Delmas Carl Hill. Robert Carter and Jack Greenberg represented the national NAACP. The local NAACP contributed Charles Bledsoe and the brothers Charles and John Scott, who were World War II veterans, grandsons of exodusters, and sons of the state’s most prominent African American attorney. Lester Goodell, former prosecuting attorney of Shawnee County (Topeka), argued for the Board of Education. The court heard testimony from all the plaintiffs, including Silas Hardrick Fleming, who provided the most compelling rationale for desegregation. The lawsuit “wasn’t to cast any insinuations that our teachers are not capable of teaching our children because they are. . . . But . . . I and my children are craving light—the entire colored race is craving light, and the only way to reach the light is to start our children together in their infancy and they come up together.”8

In August 1951 the judges ruled unanimously against the plaintiffs, citing the equality of school facilities as technically within the parameters of existing law. The Kansas panel’s decision, however, cited the expert testimony of Arnold M. Rose, a University of Minnesota sociologist, and Louisa Pinkham Holt, a psychology professor at the University of Kansas. Borrowing the language of the academic experts, the judges wrote: “Segregation of white and colored children in public schools has a detrimental effect upon the colored children. The impact is greater when it has the sanction of law. . . .” The decision, as the judges apparently intended, pushed the matter to the U.S. Supreme Court. However, the language, and the ideas that informed their decision, were incorporated into the Supreme Court’s ruling reversing the Kansas judges three years later.9

The Supreme Court’s unanimous decision on May 17, 1954, striking down de jure segregation came too late to affect many of the plaintiff’s children. That fall Linda Brown entered Curtis Junior High School, which was already desegregated. However, millions of others across the nation were, and remain, affected by the ruling. The decision denied the legal basis for segregation in Kansas and twenty other states and inspired countless court challenges of school segregation. As Cheryl Brown (Henderson), Oliver Brown’s youngest daughter, wrote four decades after the decision, Brown “would forever change race relations in this country.” From a small prairie fire of Kansas civil rights activism, the Brown decision soon grew into a fire storm that engulfed the nation.10

The Brown victory bolstered the NAACP’s legal strategy. Yet many western civil rights activists thought civil disobedience or direct action protest a necessary supplement to the court campaign. By World War II small interracial groups of westerners had initiated direct action efforts. The Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), soon to be one of the largest civil rights organizations, formed chapters in Denver and Colorado Springs in 1942 after a visit from national leader Bayard Rustin. By 1947 CORE had chapters in Lawrence, Kansas City, and Wichita, Kansas; Omaha and Lincoln, Nebraska; and Los Angeles, Berkeley, and San Francisco, California. CORE sponsored demonstrations throughout the West, the first a 1943 protest of a segregated Denver movie theater. Another early success came when the De Porres Club of Omaha, a Creighton University CORE group, through boycotts and picketing forced a number of local businesses to end job discrimination.11

Kansas CORE activists, however, failed in their first major civil disobedience campaign. On April 15, 1948, thirty University of Kansas students, including ten blacks from the university’s year-old CORE chapter, staged a four-hour “sit-down” protest at the all-white Brick’s Cafe. Lawrence police officers on the scene stood aside while KU football players tossed male CORE members onto the sidewalk. Many KU students roundly condemned the CORE demonstration. One student told the campus newspaper that white students “insist on policies of segregation that [business owners] enforce.” Without support from other students, the community, or the state NAACP, the protest ended.12

CORE was not involved in the decade’s most successful direct action campaign, the desegregation of restaurants near the University of New Mexico. In September 1947 the campus newspaper, the New Mexico Lobo, published an article describing how George Long, an African American university student, had been denied service at a nearby cafe, Oklahoma Joe’s. In response the Associated Students of the University of New Mexico, not having the power to prohibit discrimination in private establishments off campus, enacted a resolution: “If any student of the University is discriminated against in a business establishment on the basis of race, color or creed, I will support a student boycott of that establishment.” The resolution gave the ASUNM Judiciary Committee the authority to investigate cases of discrimination and, if necessary, to “declare a student boycott.” The boycott measure passed in a university-wide student referendum on October 22, 1947, by a three to one margin. Approximately 75 percent of the students cast ballots. Shortly afterward students boycotted Oklahoma Joe’s and forced the management to change its policy. Three months later the students mounted a similarly successful boycott against a downtown Walgreen drugstore. Such widespread student antipathy to discrimination led to the university’s first NAACP chapter with Herbert Wright as its president.13

Building on the boycott momentum, Long, now a university law student, and Wright wrote the Albuquerque civil rights ordinance and persuaded sympathetic members of the city commission to introduce the measure in October 1950. The ordinance passed on Lincoln’s Birthday 1952. Three years later the state legislature enacted a similar statute, nine years before the Civil Rights Act was passed by the U.S. Congress. George Long and Herbert Wright had formed a remarkable coalition of students and sympathetic off-campus organizations, including the NAACP, several churches, and Latino organizations, to achieve the first civil rights ordinance in the intermountain West.14

Ten years after the failed Lawrence demonstration a new group of Kansas students challenged segregation through direct action. On Saturday, July 19, 1958, Ron Walters, a Wichita State College freshman and head of the Wichita NAACP Youth Council, led ten African American high school and college students in a four-week sit-in at the Dockum drugstore lunch counter. The students won their battle when the regional vice-president of the Dockum chain arrived and ordered, “Serve them, I’m losing too much money.” The students quickly targeted other Wichita lunch counters over the remainder of the summer and desegregated most of them. Wichita’s students drew on the support of a much larger African American community, local churches, and the Wichita NAACP. They were also inspired by the Brown decision, the Montgomery bus boycott, and the Little Rock school desegregation effort.15

Oklahoma City followed. On August, 19, 1958, Clara M. Luper, the adviser to the local NAACP Youth Council, led thirteen black teenagers into Katz’s drugstore. The protesters occupied virtually every soda fountain seat for two days until they were served as police remained close by to prevent violence. The day after the victory at Katz’s the teenagers marched to Kress, which agreed to serve them only after removing all counter seats. Brown’s drugstore, the third of the five targeted downtown businesses, offered far more resistance. When the protesters arrived at Brown’s lunch counter, they found every seat occupied by white youths, who relinquished them only to other white customers. When a white youth assaulted a black demonstrator, the youth became the first person arrested during the Oklahoma City protests.16

When the Youth Council suspended demonstrations on September 1, it had in two weeks desegregated four of the five targeted downtown Oklahoma City businesses. Barbara Posey, fifteen-year-old spokeswoman for the council, also claimed success with at least a dozen other restaurants in the city. The first victories were also the easiest. Most Oklahoma City restaurants and public facilities remained segregated, prompting a six-year campaign, led principally by Luper but involving thousands of demonstrators and expanding from sit-ins to protest marches to a boycott of all downtown stores, and high-level negotiations with Governor J. Howard Edmondson. The Oklahoma City campaign attracted Hollywood celebrities, such as Charlton Heston, who walked a picket line in May 1961. Finally, on June 2, 1964, the Oklahoma City Council passed a public accommodations ordinance that forbade operators of public establishments from refusing to serve anyone because of “race, religion, or color.”17

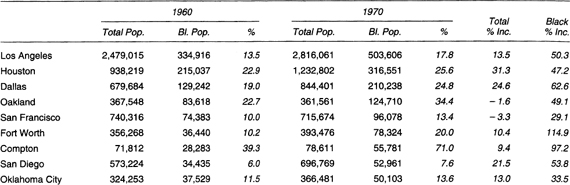

Western cities with the Largest Black Populations, 1970

(Ranked by Size of the African American Population in 1970)

Source: U.S. Bureau of the Census, Census of Population, 1960, vol. 1, Characteristics of the Population, parts 4, 6, 7, 18, 38, 45, 49 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1963), table 21; 1970 Census of the Population, vol. 1, Characteristics of the Population, parts 4, 6, 7, 18, 38, 45, 49 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1973), table 23.

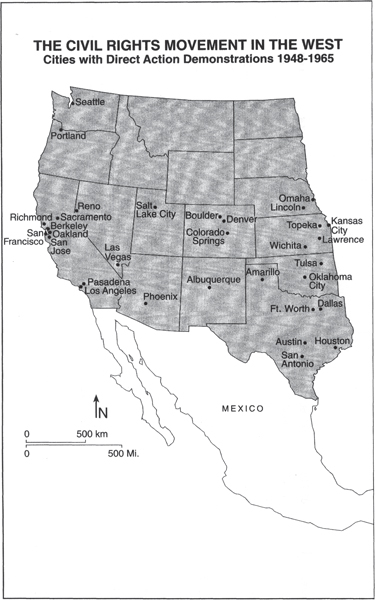

The Oklahoma City desegregation campaign was one of the longest in the West. But civil disobedience demonstrations against exclusion from public accommodations, job discrimination, housing bias, or school segregation occurred in dozens of other western cities. Merchants who refused to hire African American sales personnel drew protests in Denver and San Diego. Houston and San Antonio African Americans concentrated on restaurant exclusion while Salt Lake City and Portland protests addressed housing discrimination. Reno and Las Vegas African Americans challenged the state’s gambling and hotel industry, which excluded blacks as casino patrons and hotel guests. Even celebrity performers, such as Sammy Davis, Jr., Nat King Cole, and Lena Horne, could not stay in the hotels where they performed. In 1963 demonstrators sat in at the California state capitol and the Colorado governor’s mansion over civil rights issues. Direct action campaigns covered the West, as Seattle activist the Reverend John H. Adams recalled: “By 1963 the civil rights movement had finally leaped the Cascade Mountains.”18

The San Francisco Bay Area became the focal point of civil disobedience campaigns between 1963 and 1965. San Francisco was familiar with civil rights protest. Its CORE chapter, formed in 1948, had launched successful demonstrations against employment discrimination in the Fillmore district. Nonetheless many employers and apartment owners in San Francisco and other Bay Area cities drew the color line. San Francisco blacks were confined to two segregated residential districts, Fillmore, west of downtown, and Hunter’s Point, a World War II housing project built on a small peninsula jutting out into the bay. Even the rich and famous were not immune, as baseball star Willie Mays learned in 1957, when the baseball Giants left New York for San Francisco. Mays purchased a house in an affluent San Francisco neighborhood only after the personal intervention of Mayor George Christopher. Similarly, Oakland and Berkeley were divided by a “Maginot line” that confined most of the black community to the flatlands while affluent whites lived in the Oakland and Berkeley hills. Moreover, Black Oakland had an unemployment rate of nearly 25 percent in 1961. At least one of every three African American youths in Oakland was an unemployed high school dropout, and every predominantly black high school had a police patrol.19

In 1962 Wilfred Ussery, the new chairman of the San Francisco CORE, who later became national chairman, launched campaigns against de facto segregation and employment discrimination in downtown stores. He promised “an eyeball to eyeball confrontation with the white power structure of the city.” One year later Oakland CORE embarked on an anti-employment discrimination campaign against Montgomery Ward and gained a victory after two weeks of picketing. Montgomery Ward agreed to provide statistical data on hires by race and launched special recruitment drives that eventually opened hundreds of jobs to people of color. The CORE-Montgomery Ward settlement proved a model for other fair employment agreements with retailers.20

In 1963 James Baldwin addressed a San Francisco civil rights protest march and rally that drew more than thirty thousand supporters. Both the rally and his remarks indicated that local and national civil rights goals had merged. The march was ostensibly to support the Birmingham campaign led by Martin Luther King, Jr. However, marchers followed a banner that read, “We March in Unity for Freedom in Birmingham and Equality of Opportunity in San Francisco.” Baldwin pursued that theme: “We are not trying to achieve . . . more token integration [or] teach the South how to discriminate northern style. We are attempting to end the racial nightmare, and this means immediately confronting and changing the racial situation in San Francisco.”21

Four months after the San Francisco rally a CORE chapter was formed on the University of California, Berkeley campus. The chapter’s first target: the local branch of Mel’s drive-in restaurant, later famous in the film American Graffiti. Although Mel’s had black employees in menial positions, it refused to hire African Americans as waitresses, carhops, and bartenders. Ninety-two demonstrators were arrested in the first protest. After the second demonstration Mel’s relented and began hiring blacks in the more visible staff positions.22

After the success of the Mel’s drive-in demonstrations eighteen-year-old Tracy Simms, a Berkeley High School student; Roy Ballard, of San Francisco CORE; and Mike Myerson, a member of the UC-Berkeley radical student party, Slate, formed the Ad Hoc Committee to End Discrimination. Slate and CORE escalated Bay Area direct action protests. In February 1964 they challenged the Lucky grocery chain, specifically targeting the store on Telegraph Avenue in Berkeley with “shop-ins.” Two weeks after the protests began, San Francisco Mayor John F. Shelly mediated an agreement between the Bay Area CORE chapters and Lucky management.23

Four days later the Ad Hoc Committee moved against the Sheraton Palace Hotel for its refusal to hire African Americans. The campaign became the largest civil rights protest in the far West. Picketing began on a small scale but escalated when 123 demonstrators were arrested. Within a week approximately 1,500 demonstrators ranging from working-class youth to university professors joined the picket lines. Hundreds filled the hotel lobby and sat down, leaving a small passageway for reporters and television photographers covering the event. The following day Tracy Simms, holding a megaphone, mounted a marble table and declared to the demonstrators who had spent the night in the lobby, “The Sheraton Palace has once again shown bad faith. They have refused to sign an agreement they . . . proposed. Are you ready to go to jail for your beliefs?” Demonstrators shouted their approval and then sang “We Shall Overcome” after deciding to block all hotel doorways. When Willie Brown, one of two attorneys for the Ad Hoc Committee, proposed that the demonstrators avoid arrest by switching from blocking the doorways to holding a lobby sleep-in, they announced, “We are going to jail.” Eventually 167 demonstrators, including Mario Savio, a future leader of Berkeley’s Free Speech Movement, went to jail. But 600 demonstrators remained in the hotel until later that afternoon, when Tracy Simms announced that Mayor Shelly had negotiated an agreement with the Sheraton Palace that was binding on all the city’s major hotels. That agreement generated nearly 2,000 jobs for people of color.24

Meanwhile the San Francisco NAACP organized demonstrations against car dealerships on auto row along Van Ness Avenue. Two hundred protesters entered the Cadillac showroom to protest the dealership’s discriminatory hiring policy. One hundred and seven of them were arrested. Again Mayor Shelly intervened. This time he requested civil rights leaders call a moratorium on civil disobedience demonstrations while he appointed a committee to promote the settlement of all racial disputes by “conciliation and mediation.” Now, however, some political leaders lashed back at the demonstrators. Dr. Thomas Burbridge, leader of the auto row demonstration, was sentenced to nine months in prison, prompting James Farmer, national director of CORE, to declare, “As far as civil rights sentences . . . are concerned, San Francisco is the worst city in the country.”25

Some Bay Area protests, such as picketing of the Oakland Tribune, continued into late 1964, but the civil rights momentum began to fade partly because of the passage of the national Civil Rights Act in June 1964 and partly because white civil rights activists turned their attention to the UC-Berkeley Free Speech protests, which began after the arrest of campus CORE member Jack Weinberg while he solicited funds for civil rights organizations. Angry students converged on the squad car holding Weinberg. Mario Savio, president of Campus Friends of SNCC and a teacher the previous summer in a Mississippi Freedom School, mounted the top of the trapped squad car and urged the two thousand protesters to continue their resistance. One unidentified protester mused, “A student who has been chased by the KKK in Mississippi is not easily scared by academic bureaucrats.” For that student, Savio, and other protesters the Free Speech demonstrations were a continuation of the civil rights struggle in the South and the Bay Area.26

In terms of strategy, tactics, and objectives most western protests paralleled those waged east of the Mississippi River. However, many of these protests occurred in a milieu where African Americans were only one of a number of groups of color. The region’s multiracial population moved civil rights beyond “black and white.” The movement in Seattle and San Antonio reflects that complexity. San Antonio’s huge Chicano population created a different racial atmosphere from that of Houston, Dallas, and Forth Worth, the other major Texas centers of civil disobedience. In 1960 Mexican Americans constituted 40 percent of the population as opposed to blacks’ 7 percent. Although there had been some attempts at political alliances between the two groups, they lived on separate sides of San Antonio in largely separate worlds. “Our roots are different,” explained the local dentist and civic leader Dr. Jose San Martin. “Our problems have been different, our solutions have been different. Therefore our philosophy is different.” One of the differences was the level of discrimination. San Antonio public accommodations regularly excluded blacks. Yet a 1941 city ordinance prohibited discrimination against “anyone . . . merely because of his racial origin from one of the [Latin American] Republics.”27

Despite the ordinance, Anglo San Antonians considered Latinos nonwhite and widely discriminated against them. A few Chicano activists, recognizing their commonality with African Americans, joined the black direct action protests that began in March 1960. Leonel Javier Castillo and Perfecto Villareal, for example, organized sit-ins at San Antonio theaters that involved black, brown, and white volunteers. Moreover, black civil rights groups remembered San Antonio Congressman Henry B. González, who had led an unsuccessful effort to outlaw racial segregation while a state senator in the 1950s. Yet much of the Chicano population represented a paradox to black activists. Their presence in the city deflected prejudice from African Americans. But because they suffered less discrimination than blacks, most Chicanos, their leaders, and their organizations remained silent on discrimination, prompting San Antonio NAACP leader Claude Black to declare, “It’s like having a brother violate [your] rights. You can hate the brother much more than you would the outsider because you expected more from the brother.”28

For African American Seattle, the Asian Americans were the other group of color. Asian Americans, especially Japanese Americans, had been the largest racial minority in the city and the focus of most white prejudice before World War II. The wartime incarceration of the Japanese and the influx of African Americans to work in shipyards and aircraft plants made black Seattle the largest postwar population of color. However, Seattle’s Asians made much greater postwar educational and economic progress than blacks, which, in turn, affected white attitudes toward them. One white homeowner opposed to a 1963 city ordinance banning housing discrimination declared, “Well, Orientals are O.K. in some places, but no colored.”29 Most Japanese American organizations and leaders were neutral, and some were openly hostile to African American efforts to end housing discrimination despite their appeals for black voter support to repeal the Anti-Alien Land Act, a leading symbol of anti-Japanese prejudice. As with Chicanos in San Antonio, many Asian Americans rested comfortably with the milder discrimination they faced in comparison to black Seattleites, or feared white anger if they identified too closely with civil rights activism.

Individual Asian Americans, however, did support local civil rights efforts. Wing Luke, the first Asian American to serve on the Seattle City Council, sponsored a controversial 1963 open housing ordinance. Philip Hayasaka, executive director of the Seattle Human Rights Commission, and Donald Kazama, chair of the Human Relations Committee of the Japanese American Citizens’ League, criticized local Japanese leaders for not supporting the black civil rights movement. A Japanese American activist, the Reverend Mineo Katagiri joined the local movement, becoming the only Asian American member of the Central Area Civil Rights Committee, an otherwise all-black organization that coordinated the direct action protests of the NAACP, CORE, and other civil rights organizations. Asian American activists, such as Bernie Yang and Jim Takisaki, helped coordinate sit-ins and protest marches in Seattle. They and other young Asian Americans, like many white students of the era, genuinely identified with African American demands, which they believe stemmed from legitimate grievances. But they also believed the success of the civil rights campaign meant the end of anti-Asian discrimination. Despite the commitment of these individuals, Asian Americans and African Americans traveled different routes in seeking full-fledged citizenship in Seattle.30

De jure school segregation in Texas and Oklahoma and de facto segregation elsewhere in the region united African American parents from Houston to Seattle. The issue was hardly new. Nineteenth-century African American parents in Portland, San Francisco, Oakland, Denver, Helena, Wichita, and Topeka had waged campaigns to have their children attend integrated public schools. Segregation, however, became more acute after World War II with the rapid growth of the western urban African American population. As all-black neighborhoods emerged in western cities, school administrators allowed segregated schools to develop. After the Brown ruling in 1954, many western school boards moved slowly to desegregate facilities. Yet black parents were determined to gain for their children the educational advantages they believed were bestowed on white children. As one African American parent said in 1962, “I moved to San Francisco over ten years ago in hopes of improving the future of my children. I’ve had enough of promises from white politicians and school officials. Our children need to be taught in integrated schools in a city that refuses to perpetuate discrimination. My neighbors and I have had enough, we want change . . . we no longer accept empty promises.”31

The 1960s desegregation campaigns of African American parents in two western cities, conservative Houston and liberal Berkeley, illustrate the complexity of the effort to eradicate school segregation. Moreover, these campaigns reveal the enormous difference between “desegregation” and “integration.” The former term indicated the placing of children of various races and socioeconomic backgrounds in the same school although not necessarily in the same classes. The latter suggested that all students would have equal opportunities to learn and excel regardless of their racial or socioeconomic backgrounds. Houston and Berkeley, and indeed most public schools in the United States, desegregated in the 1960s and 1970s. Many of those schools are still grappling with integration.

In 1960 the Houston Independent School District (HISD), with 177,228 students, maintained the nation’s largest legally segregated school system. The first legal challenge to its segregated schools came in December 1956, when a lawsuit was filed in federal district court on behalf of nine-year-old Delores Ross and fourteen-year-old Beneva Williams. The most immediate effect of the lawsuit was the election to the seven-member local school board of a six-member antidesegregation majority that defiantly vowed to do everything in its power to prevent “race mixing,” which it equated with communism.32

By 1959 the NAACP’s chief attorney, Thurgood Marshall, had joined the Houston attorneys who initiated Ross v. Houston Independent School District. Nonetheless little progress was made until March 1960, when student activists at Texas Southern University launched sit-ins at the nearby Weingarten grocery store lunch counter. The demonstrations continued for a month until negotiations opened between Chamber of Commerce President Leon Jaworski and twenty-eight-year-old Eldewey Sterns, a TSU law student who was also president of the Progressive Youth Association, a coalition of student activists from TSU, Rice University, and all-black Erma Hughes Business College. When negotiations collapsed, the students resumed their protests and won significant concessions from various businesses by September 1, 1960.33

These student protests never targeted the Houston school system, but their impact, and the desire to avoid a Little Rock-style confrontation, prompted business and political elites to seek a peaceful solution to the desegregation crisis. Houston’s business establishment did not wish desegregation in either public accommodations or schools, but in order to maintain a healthy business climate—its highest priority—it supported change. Federal Judge Ben C. Connally promoted its goal when he ruled in August 1960 that the district implement a grade-per-year desegregation plan that was to begin the following September. First grader Tyronne Raymond Day took his seat with twenty-nine white classmates on September 8, 1960, and became the first African American to attend a desegregated school in Houston.34

Celebrations of Houston school desegregation proved premature. School officials implemented strict academic criteria, effectively limiting the number of black students attending formerly all-white schools. By 1964 only 3 percent of Houston’s thirty-nine thousand African American students attended desegregated schools. Consequently attorney Barbara Jordan and the Reverend William Lawson founded People for Upgraded Schools in Houston (PUSH) and called for a boycott of the city’s black high schools. On May 10, 1965, 90 percent of Houston’s black high school students stayed away from classes while two thousand demonstrators sponsored by PUSH and the local NAACP marched in front of HISD offices. The boycott and demonstration immediately prompted the school district to accelerate its timetable for desegregation of the sixth, seventh, and tenth grades. Conversely, both school district and federal court–implemented integration plans persuaded middle-class white parents to withdraw their children from local public schools. Black and Mexican parents, viewing this large-scale white flight, concluded that desegregation efforts were futile. By 1970 black and brown parents opposed busing and various other programs to promote desegregation. With the departure of middle-class whites (and, by the 1970s, blacks), integrated education seemed as remote in 1970 as it had ten years earlier.35

Berkeley’s liberal image was also tested by de facto segregation. That city’s school crisis evolved from the rapid growth of the city’s African American population. Blacks were 4 percent of the city’s population in 1940, 12 percent in 1950, 20 percent in 1960, and 23 percent in 1970. Virtually all the newcomers were working-class women and men drawn by the prospect of wartime shipyard employment and by the city’s reputation for good schools. However, black Berkeleyites quickly became part of a multicity ghetto of public housing projects that stretched along the flatlands. As one 1967 survey on school integration concluded, “segregation by race had been superimposed upon segregation by class. . . .”36

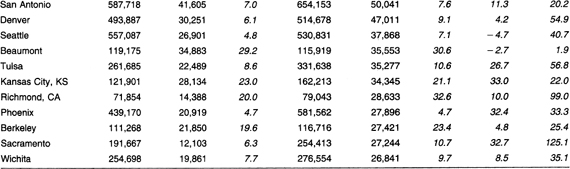

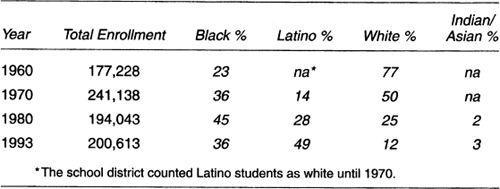

Houston School District Enrollment by Ethnicity, 1960–93

Source: William Henry Kellar, “Make Haste Slowly: A History of School Desegregation in Houston, Texas” (Ph.D. dissertation, University of Houston, 1994), 326, 353, 371.

Residential segregation supported school segregation. In 1960 the city’s public school enrollment was 56 percent white, 32 percent black, 8 percent Asian, and 4 percent Latino. Berkeley High, the only high school in the city, was desegregated, but 92 percent of the African American elementary school students attended six of the city’s fourteen neighborhood schools. As historian W. J. Rorabaugh observes, the Berkeley school district “ran two separate school systems, one by and for educated, affluent whites in the hills, the other for poor blacks in the flatlands.”37

By the time they reached one of Berkeley’s two junior high schools (the third junior high drew its students almost exclusively from the hills), African American students began to note the differences in education. Although they attended the same schools, blacks had little contact with whites and Asian Americans because most African American students entered the two lower tracks of the four-track education system. Moreover, black students, often from homes where parents had rudimentary southern educations, had few academic demands placed upon them by teachers and administrators. White middle-class parents, teachers, and peers pushed white and Asian American children harder. Not surprisingly, many black students were among the 25 percent of Berkeley’s students who scored in the bottom 10 percent on national standardized achievement tests while one third (mostly white Berkeley hills students) tested in the top 10 percent.38

Berkeley High School was hardly better for African American students since the tracking system continued the informal segregation of blacks from white and Asian American students. School activities also separated the races. Black youths were allowed to use the school swimming pool only on Friday night. Few African American students worked on the student newspaper or joined the selective school clubs that were often precursors to fraternity and sorority admission at the University of California, Berkeley and other prestigious colleges and universities. Many African American students dropped out or joined the military. Those who did graduate faced grim prospects. They were unskilled, unemployable, and unprepared for college, even though educated in the shadow of one of the nation’s most prestigious universities.39

In 1958 some black parents began to challenge this de facto segregation system. The Reverend Roy Nichols raised the issue with the school board while representing the local NAACP. Three years later he became the first African American elected to the board, joining three other members to constitute a four to one liberal majority. In 1963 the school district proposed a ten-year desegregation program that required busing to aid desegregation. When the school board announced that junior high schools would be desegregated in September 1964, angry white parents created the Parents Association for Neighborhood Schools (PANS) which immediately tried and failed to recall the entire school board in October 1964. Following that defeat, the conservative Berkeley Citizens United Bulletin urged many white busing opponents to leave the city. “If you don’t want to know the Negro mind,” declared the paper, “then it is time for you to move over the hill.”40

In September 1964 Berkeley put in place the first non-court-ordered busing plan in the United States. It called for a three-year busing program that involved a ride of no more than three miles each way. The program gave most of the city’s elementary and junior high schools a rough balance between black and white students with Asian American students making up the balance. Despite elaborate planning and preparation by school officials, which included parental visits to schools their children were to attend, prebusing exchanges of white and black students, and “race relations” training for teachers, the plan continued to engender virulent opposition. One antibusing advocate said of African American children, “They’re happy where they are!” Another suggested a gradual approach, waiting another generation, which prompted a black parent to reply, “What do you mean—it’ll come? By magic? There ain’t gonna be no magic!. We’ve gotta do it ourselves.” Another black woman said, “We’ve been waiting since the Civil War. We can’t wait any longer!” The Berkeley school superintendent, Neil V. Sullivan, a veteran of Virginia’s desegregation troubles, remarked that “the only difference between white attitudes in Berkeley and Virginia was that in Berkeley, people were ‘more polite.’ ”41

Parental fear and anxiety quickly transferred to the students, who were confused by the mixed signals they received. Desegregation worked well at most of the elementary and junior high schools. But Berkeley High became a caldron of racial tension. In the early 1960s white students ridiculed black students about their race and lower-class background. After 1965 African American students, influenced by the black power movement, raged against whites and Asian Americans regardless of their pro- or anti-integration views. Many white teachers and students were assaulted and humiliated in the halls and classrooms of the school. African American students formed the Black Student Union (BSU), which demanded and got more black counselors, curriculum materials, and “soul food” in the cafeteria. The BSU also served as monitor of the new racial divide, making it difficult for blacks and whites to maintain school friendships. Blacks dominated the football team, prompting a decline in white attendance. After 1965 virtually no whites attended postgame dances.42

Ultimately, as historian W. J. Rorabaugh explains, “black hope met white fear.” Before 1965 most of Berkeley’s African American parents believed the racial isolation of their children guaranteed failure because it denied them access to the best teachers, facilities, and equipment and ensured their marginalization once they did arrive at Berkeley High School. Yet after 1965 many African American parents began to reconsider desegregation as the sole tool to guarantee their children quality education. Those parents, influenced by black nationalists and radicals, called for control over neighborhood schools. By 1969 many of them had become as adamantly opposed to busing as were their white and Asian American counterparts. Despite Berkeley’s reputation as one of the most liberal cities in the nation, antibusing advocates remained a sizable force in local politics. Thus school integration was challenged by various racial and political groups pursuing their own uncompromising agendas.43

As the campaigns in Houston and Berkeley illustrate, school desegregation without the concomitant neighborhood residential integration usually generated white fear and flight from the public schools, if not the city itself, and ultimately resegregation. Moreover, the decades-long public controversy over desegregation poisoned goodwill among all groups—whites, blacks, Asians, and Latinos—prompting the last three to vie among themselves for control of shrinking school districts. By 1980 many public school systems in western cities had failed to integrate their classrooms, and some were giving up on desegregation efforts, leaving students of color isolated in increasingly impoverished districts.

On August 11, 1965, in a predominantly African American neighborhood near Watts, California Highway Patrolman Lee Minikus stopped twenty-one-year-old Marquette Frye, who had reportedly been driving dangerously. Frye failed a roadside sobriety test and was arrested. His mother, Rena Frye, appeared from the family home nearby. A crowd gathered, and more highway patrol and Los Angeles police arrived on the scene. Bottles were thrown, answered by tear gas. The Watts riot began with this incident. It became the largest African American civil uprising in the nation’s history. When the conflict was over, thirty-four people were dead: twenty-nine blacks, three Latinos, one Asian American, and one white. Behind such statistics were names: Charles Fitzer, Rena Johnson, Joe Maiman, Ramón Hermosillo, Eugene Simatsu, Ronald Ludlow, four-year-old Bruce Moore, the youngest, all killed in the disturbance, and twenty-seven others. The uprising of 1965 was not confined to Watts proper; it spread throughout south central Los Angeles encompassing an area as large as San Francisco or Manhattan. Even though the riot zone was larger than the community itself, after 1965 the name Watts symbolized anger, alienation, and resentment. Watts also represented in its poverty and, by 1965, its violence the possibility of a disturbing future for urban America.44

Watts proved rich in irony. Residents who lived in bungalows and low-rise housing projects on sun-drenched, palm tree-line streets were not considered likely candidates for urban rioting in 1965. African American Californians had voting rights, public accommodations access, and theoretically integrated schools. They seemed far removed from the conditions that sparked major civil rights confrontations in Birmingham or Selma. Even Marquette Frye, the catalyst for the uprising, came from a background that belied the Watts image. Although born in Lima, Oklahoma, Frye had been reared in Hannah, Wyoming. “People [in Wyoming] were much better,” he recalled after his arrest. “The school curriculum was better. The kids’ vocabularies were better. When I came to California, the kids here resented my speech, they resented my intelligence. . . . In Wyoming . . . there were only about eight Negroes in school. . . and we were accepted by the whites. When we came to California, we got into an all-Negro school. . . . I made ’A’s and ’B’s back in Wyoming. But here I kept getting suspended for fighting. . . .”45

The origins of the confrontation in August 1965 are rooted in developments that evolved in Watts from the 1920s through the 1960s. From its founding in 1903 Watts had been a portal through which laborers entered the Southern California economy and its homeowning class. It was unique among Los Angeles suburbs; from its beginning black, Latino, and white migrants purchased houses and small farms. By 1940 African Americans comprised 31 percent of the community’s nearly seventeen thousand residents. The arrival of twelve thousand African Americans during World War II gave the community a black majority for the first time.46

The new residents entered Watts as tenants and job seekers rather than aspiring homeowners. Black newcomers doubled up in single-family dwellings or aging apartments. Neighboring suburban communities, such as Lynwood and Compton, continued their opposition to residential integration, prompting Robert C. Weaver to write in 1945 that Watts had assumed “the characteristics of a racial island.” However, Arna Bontemps captured the psychological as well as physical boundaries of this evolving ghetto: “A crushing weight fell on the spirit of the neighborhood when [Watts] learned that it was hemmed in, that prejudice and malice had thrown a wall around it.”47

Watts steadily declined into a slum. In 1950 the city of Los Angeles placed three of its eleven new public housing projects—Jordan Downs, Nickerson Gardens, and Imperial Courts—in Watts. The three projects housed nearly ten thousand people in a community of less than twenty-six thousand. Because of eligibility requirements for public housing residents, nearly all the residents were on some form of public assistance, unfortunate families that other communities either could not or would not accommodate. New residents arrived in the community when middle-class black families, no longer confined to Watts by restrictive covenants, began moving into West Los Angeles. Their departure increased the concentration of low-income, poorly educated residents in Watts. With no black elected officials at the city or county level in Los Angeles and no organizational voice, Watts interacted with the rest of Los Angeles in the 1950s primarily through menial work, welfare agencies, and the police.48

By 1960, 85 percent of Watts’s 28,732 residents were African American. In the 1950s unemployment in Los Angeles declined; it increased in Watts. By the beginning of the 1960s, 15 percent of the residents were without jobs, including a growing number of “long-term unemployed,” and 45 percent of the community’s families were below the poverty level, earning under four thousand dollars annually. Watts residents had the lowest educational and income levels among African Americans in the city. By the 1960s many other black Angelenos treated this community with contempt. Eldridge Cleaver recalled how the name Watts became an insult, “the same way as city boys used ‘country’ as a term of derision. . . . The ‘in crowd’ . . . from L.A. would bring a cat down by saying he was from Watts. . . .”49

Watts, however, was not all of black Los Angeles. Only 9 percent of the city’s African American residents lived there in 1960. The overwhelming majority of African American Angelenos resided in various working- and middle-class neighborhoods known collectively as South Central Los Angeles, while Baldwin Hills stood at the apex of the African American socioeconomic spectrum in Los Angeles. Although virtually every other African American community in the region had similar class division, in no other western black community was the separation so stark. Black median income in Baldwin Hills in 1960 was $12,000, well above the citywide median of $5,325 or the black median of $3,618. That separation manifested itself in the differing goals of African American leaders in the early 1960s. Many black Angeleno leaders invested heavily in the early 1960s campaign for political representation in city government, an effort that diverted considerable organizational energy and skill to local politics from civil rights activity or antipoverty efforts and may have prematurely led many middle-class and working-class Angelenos outside Watts to embrace the illusion that significant progress was being made. The emphasis on political power persuaded the direct action champion Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., who in 1962 met with Tom Bradley, the Reverend H. H. Brookins, and other local leaders to plan strategy to elect an African American to the Tenth Council District. Throughout the affluent west side integration was the watchword for the area’s upwardly mobile African Americans. For them the weapon of choice was the ballot box.50

As 1963 began, black Los Angeles had no representation at the city or state level and only one federal representative, Augustus Hawkins. Before the year ended, the city’s African Americans mounted a remarkable campaign that elected three city council members (out of thirteen). Billy Mills represented the Eighth Council District, Gilbert Lindsay, the Ninth district, and Tom Bradley was elected in the Tenth district. These council members represented distinct constituencies. Mills and Lindsay were part of the Jesse Unruh-Mervyn Dymally political machine. Mills’s predominantly black working-class district was the heart of South Central Los Angeles. Lindsay’s Ninth District was predominantly Latino and had formerly been represented in the city council by Edward Roybal, who in 1962 became the member of Congress from East Los Angeles. Tom Bradley meanwhile represented a district noted for its black and Jewish middle-class political reformers who opposed the Unruh machine. Robert Ferrell, who was to represent the Eighth District in 1974, characterized the class differences between the Eighth and Ninth districts and the Tenth as “cotton socks vs. silk stockings.”51

Ten months after the Watts uprising the cry “black power” was first heard during a Canton, Mississippi, speech by Stokely Carmichael. Yet those words and what they symbolized were as applicable to post-1965 South Central Los Angeles or West Oakland as to any Mississippi community. Those two California communities produced the organizations that articulated the demands and aspirations of the two major streams of black power consciousness for the entire nation. Within a year of the Watts uprising Maulana Ron Karenga founded United Slaves (US), extolling cultural nationalism, while Huey Newton and Bobby Seale created the Black Panther party, epitomizing revolutionary nationalism.52

On the night of Marquette Frye’s arrest in 1965, twenty-three-year-old Maulana Ron Karenga taught a Swahili class at Frémont High, Frye’s high school. Karenga, born in 1941 in Parsonburg, Maryland, as Ronald McKinley Everett, was enrolled in the Ph.D. program in political science at UCLA while employed as a Los Angeles County social worker and part-time teacher at Frémont. Following the Watts uprising, Karenga emerged as the most prominent black nationalist in Los Angeles. In February 1966 he organized the first Watts Summer Festival, to honor the dead and recast the “riot” as a revolt. The festival attracted 130,000 people. Karenga also formed the Sons of Watts and the Simbas (young lions), which recruited former gang members, while his Community Alert Patrols monitored police activity in African American neighborhoods. Karenga was a major promoter of “Freedom City,” a proposal to allow Watts and other sections of black Los Angeles to become independent. In the fall of 1966 Karenga and Tommy Jacquette were hired by the Westminster Neighborhood Association (WNA), which had received eight hundred thousand dollars in federal antipoverty funds. Jacquette recruited unemployed male youths into the program, which paid them twenty dollars per week for taking courses in remedial English, math, reading, and African American history. Karenga was the principal program instructor, teaching the history courses and Swahili-language classes. By the end of the year the WNA with 350 student-workers was “the largest employer in Watts.”53

Karenga was secretive about the founding of United Slaves (US), allowing only that it was established soon after the Watts uprising. However, he promoted his views in a series of 1966 interviews with national newsmagazines. In an interview with John Gregory Dunne, Karenga dismissed the civil rights movement’s goals: “Why integrate? Why live where we are not wanted? . . . You’ve got to get power of your own, because power listens to power. . . . By setting an example of fearlessness, education, pride and culture, we give the black man something to fight for.” To Andrew Kopkind he reported, “Blacks should control their own communities. . . . We are free men. We have our own language. We are making our own customs and we name ourselves. Only slaves and dogs are named by their masters.” With his ability to gain media attention and his profile in black Los Angeles, Karenga soon eclipsed all rivals except Imamu Amiri Baraka of Newark as the leading black nationalist in the nation.54

The origins of the Black Panther party in Oakland reveal a similar repudiation of the civil rights struggle. The Panthers’ Marxism, however, cast them as “the greatest threat to the internal security of the country,” according to FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover. Black Panther founders, Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale, conducted their first meeting at a West Oakland clubhouse on October 15, 1966. The two had histories much like those of thousands of black Oakland residents, whom the new party vowed to defend. Born in Monroe, Louisiana, Newton came west to Oakland with his family in 1945, when he was three. Seale was born in Dallas, Texas, in 1936 but grew up in Codornices Village, the sprawling housing project that straddled the Berkeley-Albany border. Newton and Seale were members of the generation of black westerners who, unlike their shipbuilding parents, could not secure places in the postwar Bay Area economy. They were uninspired in school. Newton later wrote bitterly of his years in the Oakland public schools: “Not one instructor ever awoke in me a desire to learn more or question or explore the worlds of literature, science, and history. . . . They [tried] to rob me of my . . . worth . . . and nearly killed my urge to inquire.” Moreover, Newton and Seale found little employment as teenagers and had numerous conflicts with the local police. In 1961 they met at Oakland City College and were drawn together by their mutual admiration for Malcolm X, “street brothers,” and socialist theories.55

The Panthers embraced a philosophy that immediately placed them in opposition with cultural nationalist groups such as US. Like all post-Watts nationalist organizations, they denounced the civil rights movement and predicted that only violent revolution would eliminate racism and oppression from African American life. However, the Panthers called for armed self-defense of black communities, urged African Americans to embrace Marxism, and espoused alliances with other U.S. radicals and with revolutionary governments throughout the world. They believed that direct confrontation with police across the United States would hasten the revolutionary struggle they and their allies were destined to win.56

Before May 1967 the BPP had only twenty members and was unknown outside Oakland. Most of its members, like its first recruit, sixteen-year-old Bobby Hutton, were “street blacks.” One new member, Ramparts writer Eldridge Cleaver, provided an intellectual core to the Panther program as well as valuable connections to wealthy white liberals and radicals. Yet a Panther protest in Sacramento propelled this small party into international prominence. On May 2, 1967, virtually the entire membership arrived at the state capitol in Sacramento armed and dressed in the Panther uniform of black leather jacket, beret, turtleneck sweater, and pants. Alarmed capitol employees quickly retreated from the unexpected visitors, and Governor Ronald Reagan, giving a speech on the capitol lawn, was hustled away by security agents. Ostensibly there to protest a recently introduced bill that would have prohibited the carrying of firearms in public places, the Panthers inadvertently entered the state assembly chamber before a barrage of reporters and photographers who made them the most recognized “black militants” in the nation.57

Panther membership rose quickly after this media event and information on their philosophy became known. By 1968 the BPP had twelve hundred members in chapters throughout the nation. They also launched highly publicized but short-lived alliances. The first was with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), “drafting” its leader, Stokely Carmichael, into their organization with the rank of field marshal and giving him the responsibility for “establishing revolutionary law, order, and justice” east of the Continental Divide with the Panthers holding authority west of the Rocky Mountains. The Panthers also linked themselves with the mostly white Peace and Freedom party (PFP), founded by Robert Scheer, Michael Lerner, Tom Hayden, and Jerry Rubin. In 1968 the party ran Eldridge Cleaver and Jerry Rubin as its presidential and vice-presidential candidates.58

With success came increasing scrutiny and harassment by local, state, and federal authorities. Between 1967 and 1969 Panthers across the nation confronted police in clashes that left ten BPP members and nine police officers dead. They gained the attention of J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI, which initiated the COINTELPRO campaign to disrupt them and other radical organizations. The increased harassment also brought notoriety, as evidenced by the huge “Free Huey” rallies staged after Newton was arrested and tried for the killing of the Oakland police officer John Frey. One rally before the Oakland courthouse where Newton was jailed attracted three thousand in a rainbow coalition of Newton supporters, including Whites for the Defense of Huey Newton, the Asian American Political Alliance, whose members held Free Huey signs in Mandarin Chinese, Japanese, and Tagalog, and young Latinos who appeared in tan bush jackets and brown berets anticipating the rise of the Brown Berets. Celebrities such as Yale president Kingman Brewster, Leonard Bernstein, Marlon Brando, Jane Fonda, Harry Belafonte, Jessica Mitford, James Baldwin, Ossie Davis, Susan Sontag, Norman Mailer, and Candace Bergen all supported various Panther efforts.59

The Panthers never found common ground with Maulana Ron Karenga’s US. Both the BPP Southern California chapter and US operated in South Central Los Angeles and drew from the same constituency of impoverished, alienated black youth. To appeal to these men, many of whom had gang backgrounds, both organizations promoted their street-wise bravado, which quickly devolved into a series of ganglike street confrontations culminating in a bloody 1969 shoot-out on the UCLA campus that left Los Angeles Panthers Alprentice (“Bunchy”) Carter and John Huggins dead in a dispute over the first director of the campus’s new Afro-American Studies Center.60

The Black Panther party and United Slaves left an ambiguous legacy. A Panther-led political insurgency in Oakland helped elect Lionel Wilson the city’s first black mayor in 1981. The party’s free breakfast and education programs generated renewed interest in pre-adolescent nutrition and education for urban children. The Panthers borrowed from and inspired parallel defense organizations, including the American Indian Movement (AIM), the Brown Berets, the Puerto Rican Young Lords, and the Red Guards of San Francisco’s Chinatown. Maulana Ron Karenga’s US provided the foundation for the largest African American identification with Africa since the Garvey era. Both the current popularity of the end-of-year celebration Kwanzaa, which Karenga created in 1965, and Afrocentricity, which he influenced, are part of the US legacy. Both organizations also encouraged the rise of black (or ethnic) studies programs on university campuses with the first black studies program at San Francisco State College in 1968, following almost a year of violent confrontation between the Third World Liberation Front, a coalition of black, Asian, Latino, and Native American students, and campus administrators, led by college president S. I. Hayakawa.61

Neither US nor the Panthers achieved the transformation of black urban America they envisioned as counterinsurgency campaigns and federal and local authorities reduced their ranks and undermined their confidence. By 1970 Karenga, Newton, Seale, and Cleaver were incarcerated or in exile. Internal conflicts over philosophy and discipline also took a toll on both organizations. Neither the Panthers nor US developed significant middle-class African American support to offset the loss of their “natural constituency,” young black males who by the early 1970s were destroyed by drugs or lulled into nihilistic violence and political apathy.

Nor could the Panthers or US successfully address the problem of gender equality. Both groups extolled the role of progressive black women in the coming revolutionary struggle. However, neither could fashion a program that promoted gender equality while many organization leaders and members insisted on maintaining male prerogatives that reinforced traditional gender roles. US embraced a mythical African cultural past that allowed no gender equality. The Panthers wrestled with the issue and alternated between progressive and reactionary stands. Certainly by the 1970s women outnumbered men in the party and, following Elaine Brown’s assumption of leadership, had significant roles in its programs. But ultimately Brown and many other women left the Panthers because of male resentment of their impact on party programs and its image.62

Secondly, both groups made their appeal almost exclusively to “street blacks,” the men and women of a rapidly growing black underclass. The Panthers, US, and virtually all post-Watts nationalist organizations made this lumpen proletariat the new political icon. The pre-1965 civil rights movement avoided championing the cause of blacks with criminal records. Post-1965 nationalists recruited gang members, drug dealers, pimps and prostitutes, thieves and murderers, calling them revolutionaries if they died in confrontations with police and political prisoners, if they landed in jail. These street fighters were “authentic” revolutionaries, their criminality dismissed as quasi-revolutionary activity and their confrontations with police hailed as challenges to racist oppressors. All blacks, regardless of background, were encouraged to emulate these street brothers as the revolutionary vanguard and follow their leadership.63

Some African Americans criticized the new orthodoxy. In an editorial following the slayings of Carter and Huggins at UCLA, the Sentinel, a black Los Angeles newspaper, challenged the claims of the cultural and revolutionary nationalists to speak for the African American community. “The whole problem-solving process in this community has been captured by a small, aggressive body of people whose self-sustainment needs preclude them from . . . making fair decisions in the name of the community. They will claim noble intentions but in the final analysis they mean to rule by any means feasible. That includes from the barrel of a gun.” African American opinion never coalesced around nationalist visions of power and “authenticity.” Nonetheless the image of street “outlaws” as a potential revolutionary force had, and continues to have, an enormous impact on African America.64

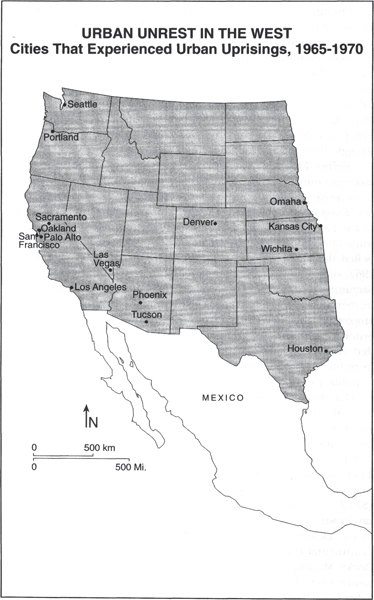

Black nationalism swept the West and the nation following Watts and the rise of US and the Black Panther party, ensuring that African American rage and frustration knew no regional boundaries. Racial violence broke out in San Francisco, Tucson, and Phoenix, in 1966, in Houston and Seattle in 1967, and in Omaha (the birthplace of Malcolm X), Portland, Oakland, Las Vegas, Denver, Kansas City (Kansas), and Wichita by the end of the decade. There was nothing particularly “western” about these uprisings. If impoverished black communities in Denver, Seattle, or Los Angeles seemed less visually alienating than Harlem, South Side Chicago, or Southeast Washington, the underlying conditions were remarkably similar. Thus cultural or revolutionary nationalism that emerged on the streets of West Oakland and South Central Los Angeles found ready acceptance whether in Chicago, Atlanta, Boston, or New York.

Tens of thousands of African American westerners saw their lives improved by the pre-1965 civil rights movement. Employment and educational opportunities also grew during the black power era of the late 1960s. Yet after Watts there was a palpable decline in optimism among middle-class and working-class black westerners about the region’s potential to offer them both opportunity and racial justice. Even the successful knew that thousands of other black people in South Central Los Angeles, Denver’s Five Points, Seattle’s Central District, or Houston’s Fourth Ward faced a daunting task in overcoming the physical and psychological barriers constructed by centuries of racism and poverty, particularly in an era of declining sympathy for their condition. These westerners had finally abandoned the search for a racial “promised land.” Instead they chose political and cultural struggle because for them the West was the “end of the line both socially and geographically. There was was no better place to go.”65