Freedom in the Antebellum West,

For much of the nineteenth century African Americans viewed the West as a place of economic opportunity and refuge from racial restrictions. The first public expression of that sentiment appeared in 1833 at the Third Annual Convention for the Improvement of the Free People of Color. The convention met in Philadelphia, far removed from the region under consideration, but it nonetheless endorsed western settlement, especially the emigration of blacks to Mexican Texas, over a return to Africa. “To those who may be obliged to exchange a cultivated region for a howling wilderness,” declared its resolution, “we recommend, to retire into the western wilds, and fell the native forest of America, where the ploughshares of prejudice have as yet been unable to penetrate the soil.”1 This resolution reflected the steady erosion of black rights more than familiarity with western conditions. Even so, the delegates subscribed to a widely held American belief that migrating offered a chance to start anew.

Such faith proved elusive. White western settlers rapidly constructed familiar racially based political and economic restrictions. Texas, which in the 1820s offered hope to many African Americans, entered the Union in 1845 as a slave state. By 1860 Texas had 355 free blacks and 182,000 slaves, clear proof that Anglo Texas liberty and black freedom had become incompatible. California’s 4,000 African Americans, all nominally free, constituted 75 percent of the free black population in the West. Yet successive antebellum California legislatures built what historian Malcolm Edwards calls “an appallingly extensive body of discriminatory laws.” These laws denied voting rights, prohibited African American court testimony, and banned black homesteading, jury service, and marriage with whites. Territorial legislatures in Oregon, Kansas, Utah, and Nebraska enacted similar restrictions.2

Despite their small numbers, African American westerners challenged these restrictions. Occasionally an individual simply moved himself and his family from harm’s way. Missouri farmer George Washington Bush, like thousands of others in the 1840s, caught “Oregon fever.” In 1844 he uprooted his wife and six children, and with four other families set out on an eight-month, two-thousand-mile journey to the Pacific Northwest. On September 5, 1844, near Soda Springs in present-day Idaho, Bush confided to fellow traveler John Minto that “he should watch when we got to Oregon, what usage was awarded to people of color.” Bush resolved that “if he could not have a free man’s rights, he would seek the protection of the Mexican Government in California or New Mexico.” The Bush party eventually reached Oregon, but unlike the majority of white settlers who spread out over the Willamette Valley south of the Columbia, he chose the sparsely populated area north of the river. A recently passed black exclusion law would be difficult to enforce in that area. Bush’s decision initiated migration north of the Columbia and led to the organization of Washington Territory.3

On other occasions a lone voice protested evolving discrimination. In 1851 Abner Hunt Francis reported to the country’s abolitionists through articles in Frederick Douglass’ Paper the impact of Oregon Territory’s black exclusion law on its one hundred African American residents. Abner’s brother, O. H. Francis, a successful Portland merchant, had been arrested under the provisions of the law. Although Abner Francis railed against the statute, which allowed “the colored citizen [to be] driven out like a beast in the forest” and vowed to “suffer severely” if it helped bring about the law’s repeal, he also noted that many Portland citizens had petitioned for his brother’s exemption from the law and its eventual repeal.4

Organized political and legal action, however, dominated resistance tactics, especially in California, where a small but articulate African American community confronted racially discriminatory legislation. In the process they initiated the first civil rights campaign in the West. California’s antebellum black population comprised the first voluntary African American migrants to the West. In an 1854 letter to Frederick Douglass, black San Franciscan William H. Newby aptly described his new city of thirty-five thousand inhabitants: “San Francisco presents many features that no city in the Union presents. Its population is composed of almost every nation under heaven. Here is to be seen at a single glance every nation in miniature.” Newby depicted the entire population, but his words applied equally to the diverse array of African Americans gathered in the golden state. In 1850 California had nearly one thousand blacks from north and south of the Mason-Dixon Line as well as a foreign-born population of Afro–Latin Americans from Mexico, Peru, and Chile and a significant population of Jamaicans. California was the only state where freeborn women and men from such northern states as Massachusetts, New York, Illinois, and Ohio rubbed shoulders with slaves from Georgia, Alabama, Tennessee, and Texas. That mix, particularly with its leadership drawn disproportionately from New England abolitionist circles, produced a community capable of protecting its interests.5

Most black migrants trekked the main route from Westport, Missouri, through the Rocky Mountains, across the Great Basin, and over the Sierra Nevada range to northern California or the southern route from New Orleans or Fort Smith, Arkansas, across Indian Territory, Texas, northern Mexico, Arizona, and the Mojave Desert into southern California. Both routes tested the endurance and stamina of the strongest men and women regardless of their race.

There is no record of an overland company (as the wagon trains to California were called) composed solely of African Americans. Yet these companies usually had some black members. Typical was a forty-niner group that included “105 men, 15 Negroes and 12 females.” Sometimes the migrants traveled alone. Margaret Frink described a black female she encountered in 1850 near the Humboldt Sink, the desert just east of the Sierra Nevada. Frink recalled the woman “tramping along through the heat and dust, carrying a cast iron bake stove on her head with her provisions and a blanket piled on top—all she possessed in the world—bravely pushing on for California.” For some the trail proved fatal. One overland traveler wrote that “a white woman and a colored one died yesterday of the cholera.”6

Most African Americans moved to California for economic reasons, pursuing the promise of quick wealth in the goldfields or in burgeoning San Francisco and Sacramento. The costs exacted by migration selected out only those African Americans with means or with access to credit. For the intrepid, the effort seemed well worth the dangers. The New Bedford (Massachusetts) Mercury in September 1848 described an encounter between a black man walking near the San Francisco docks and a white gold seeker just off a ship. When the newcomer called on the black man to carry his luggage, the African American responded with an indignant glance and turned away. Having walked a few steps, he turned toward the newcomer, drew a small bag from his bosom, and said, “Do you think I’ll lug trunks when I can get that much in one day?” The sack of gold dust was estimated by the newcomer to be worth over one hundred dollars.7

Three years later Peter Brown described his new life as a gold miner to his wife, Alley, in Ste. Genevieve, Missouri: “I am now mining about 25 miles from Sacramento City and doing well. I have been working for myself for the past two months . . . and have cleared three hundred dollars. California is the best country in the world to make money. It is also the best place for black folks on the globe. All a man has to do, is to work, and he will make money.”8

Such reports of opportunity in the goldfields ensured a steady flow of African Americans to California. By 1852 the black population had doubled to 2,000 women and men. As with all mining frontiers, it was overwhelmingly male. Of the 952 blacks counted in the 1850 census, only 9 percent were women. Ten years later, when black California numbered 4,086 inhabitants, black women constituted only 31 percent of the total population.9

Slightly more than half of California’s African Americans in the early 1850s headed for the mother lode country, a band of gold-mining communities stretching south along the western slope of the Sierra Nevada from the Trinity River for four hundred miles to the Tuolumne River. A hundred thousand miners from five continents lived there. A few black gold seekers found wealth. An African American sailor known only as Hector in 1848 deserted his naval squadron ship, Southampton, at Monterey, went to the mother lode, and returned a few weeks later with four thousand dollars in gold. Another black man, known only as Dick, mined a hundred thousand dollars in gold in Tuolumne County in 1848 only to lose it at San Francisco gambling tables. While his was one of the largest discoveries by any miner, the average black miner made five to six dollars per day.10

African American miners usually worked in integrated settings, preferring the company of Chinese, Latin American, European, or white New Englander miners, all less prejudiced than southerners and midwesterners. On occasion black miners grew numerous enough to support a community. In 1852 a small predominantly black community called Little Negro Hill grew up around the lucrative claims of two Massachusetts-born black miners working along the American River. A store and boardinghouse became the nucleus for a concentration of African American residences. Little Negro Hill attracted Chinese and Portuguese miners and eventually American-born whites. By 1855 it was described as a settlement of four hundred, with “scores of hardy miners making good wages.” Other integrated mining settlements evolved as well: a second Negro Hill near the Mokelumne River, Union Bar along the Yuba River, and Downieville, one of the few permanent settlements in the mother lode. Downieville was founded in 1849 by a Scotsman, William Downie, who led a party of nine miners, including seven blacks, to the site where the town now stands.11

Initially African American miners encountered little difficulty. J. D. Borthwick, an Englishman who spent three years in the gold-fields, came to that conclusion in 1851, when he wrote: “In the mines the Americans seemed to exhibit more tolerance of negro blood than is usual in the states. . . .”12 The popularity of black-owned boardinghouses and restaurants in the gold country, the apparent ease of African Americans in establishing mining claims, the relaxed racial etiquette of the saloon and gambling house, where multiracial patrons casually interacted with little tension, attest to the appealing idea that racial barriers had fallen as all men and women had become, to quote a popular gold rush–era poem, “to gold a slave.” Such equality did not last. As frontier conditions quickly gave way to settlement, first in San Francisco and Sacramento and by 1860 in the gold country itself, traditional racial parameters were soon established.

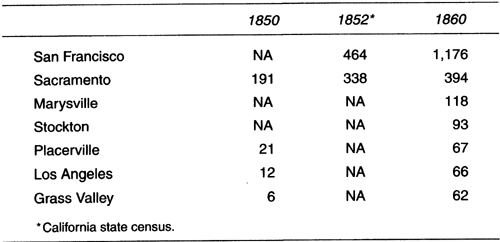

The population center of antebellum black California was in the mother lode, but its political, intellectual, and cultural centers emerged in San Francisco and Sacramento. The 1852 state census listed 464 African Americans in the state’s principal seaport and 338 in the state capital. Such figures, however, underestimate the significance of the two cities as points of arrival for newcomers destined for the goldfields, as winter quarters, as entertainment centers for black miners, and as potential areas of retirement for both successful and unsuccessful argonauts. Eventually the cities claimed the residential allegiance of most blacks.

Most African Americans in gold rush California, including many community leaders, were free and from eastern cities. Typical of such San Francisco leaders were James P. Dyer of New Bedford, Massachusetts, and former Philadelphians Mifflin Gibbs and Peter Lester, while Sacramento claimed former Baltimorean the Reverend Darius Stokes. Even ex-slaves from rural backgrounds, such as Georgia-born Mary Ellen Pleasant and former North Carolinian James R. Starkey, found western urban life far more congenial.

Antebellum urban California blacks pursued a range of occupations similar to those available in eastern cities, although the gold-enriched economy provided significantly higher wages for the most menial positions. Black stewards on river steamers earned $150 a month during the 1850s. At the top of this employment hierarchy stood the cook. Of the 464 blacks in San Francisco in 1852, 67 were cooks. Sacramento, with 338 black residents, had 51 African American cooks. The designation cook, however, obscured the vast range of incomes African Americans received in this occupation. Mary Ellen Pleasant’s reputation as a cook had preceded her when she arrived in the city in 1852, and she was besieged at the wharf by men anxious to employ her. She ultimately selected an employer who promised $500 a month, a gold miner’s average income. Next came barbers and stewards. San Francisco in 1852 had 22 black stewards and 18 black barbers, Sacramento 8 and 23 respectively. Yet most African American men and women worked at unskilled positions—“white-washers,” porters, waiters, maids, and servants—in businesses and private homes.13

A few fortunate African Americans in San Francisco became wealthy business owners. Mary Ellen Pleasant, perhaps the most celebrated black property owner in antebellum California, owned three laundries and was involved in mining stock and precious metals speculation. John Ross operated Ross’s Exchange, a used-goods business, while James P. Dyer, the West’s only antebellum black manufacturer, began the New England Soap Factory in 1851. Former slave George Washington Dennis managed a successful livery business in the city. Mifflin W. Gibbs, who arrived in San Francisco in 1850 with ten cents and initially worked as a bootblack, in 1851 formed a partnership with fellow Philadelphian Peter Lester to operate the Pioneer Boot and Shoe Emporium, a store that eventually had “patrons extending to Oregon and lower California.” By 1854 black San Francisco could proudly boast of “two black-owned joint stock companies with a combined capital of $16,000, four boot and shoe stores, four clothing stores, two furniture stores, two billiard saloons, sixteen barbershops, and two bathhouses . . . 100 mechanics, 100 porters in banking and commercial houses, 150 stewards, 300 waiters, and 200 cooks.” Much of black California’s wealth stemmed, however, from rapidly appreciating urban real estate. During the first statewide Colored Convention in 1855, delegates listed assets of $750,000 for California’s population.14

The goldfields proved a temporary home for African American miners, but black urban residents created permanent communities. San Francisco’s black community was the first indication of this permanency. Between 1849 and 1855 most African American residents settled near the waterfront and expanded slowly from there. The eastward-facing slope of Telegraph Hill was home to most blacks in a larger mixed community of color that evolved in a section derisively termed Chili Hill because of the concentration of Latin Americans. Occupying the same neighborhood of tents, shacks, saloons, hotels, and gambling houses, Mexican American, Chilean, and African American sailors, miners, and laborers pooled resources in one of the earliest examples of cooperation among people of color. In 1854, for example, Mexican Americans and African Americans organized a pre-Christmas masquerade ball.15

Middle-class African Americans lived throughout the city, often on the premises of their shops. For them the parameters of the black community were cultural rather than physical. They created institutions that brought together blacks from throughout the city for spiritual and social support. As usual the church became the first permanent institution. The first African American church in California was St. Andrews African Methodist Episcopal (AME), organized by the Reverend Bernard Fletcher in Sacramento in 1851. The following year the Reverend John Jamison Moore, a former slave, founded the AME Zion Church of San Francisco; four years after its founding the church occupied a brick building and had a Sabbath school with fifty pupils and a library of 250 books. The Third Baptist Church was also organized in 1852 by thirteen congregants led by Joseph Davenport. Later in the year came Bethel AME church, led by a white clergyman, the Reverend Joseph Thompson, before the arrival of the Reverend (later Bishop) Thomas M. D. Ward in 1854. Also in 1854 the Reverend Fletcher arrived from Sacramento to organize St. Cyprian AME Church, which quickly became the largest church in the city as well as the site of the first public school for black children in California. The role of these churches as moral and spiritual base in an underdeveloped urban society was important in its own right, but they also assumed other responsibilities. The congregations supported orphans and widows with food and money, aided victims of such natural disasters as the 1861 Sacramento flood, raised money to assist the sick and wounded soldiers of the all-black Fifty-fourth Massachusetts Regiment during the Civil War, and aided both California Indians and southern freedmen immediately after 1865.16

Antebellum California urban African Americans promoted cooperative endeavor and community building. In December 1849 thirty-seven black San Francisco men, mostly ex-New Englanders, formed the West’s first black self-help organization, the Mutual Benefit and Relief Society, to assist newcomers and encourage other African Americans to emigrate to California. This society was succeeded four years later by the San Francisco Atheneum, a two-story men’s club housing a first floor saloon for social gatherings, but whose second story, called the Atheneum Institute, soon became a center of black intellectual life. Former New Englanders, New Yorkers, and Pennsylvanians organized the institute, electing Jacob Francis, a Rochester, New York, native and an associate of Frederick Douglass, as its first president. Within a year the institute had eighty-five dues-paying members who raised two thousand dollars to support an eight-hundred-book library. The Atheneum hosted community debates over abolitionist political activity and emigration to Latin America or Africa. It also housed strategy sessions on the various legal challenges to slavery and to California’s antiblack laws. Later the institute led the campaign for a statewide African American newspaper, Mirror of the Times, which in 1856 became the first antebellum African American newspaper west of St. Louis.17

The black population of Sacramento also grew rapidly during the early 1850s. Most blacks were cooks, barbers, and boardinghouse keepers. In the last category the Hackett House, owned by a former Pennsylvanian, J. Hackett, was considered the largest African American business in the city and the center of social and political life for black Sacramento. A second, smaller hotel, the St. Nicholas, was distinctive for the period in that it employed three Chinese men. The black population was concentrated in residences along the banks of the Sacramento River, sharing its neighborhood with Mexican and Chinese settlers. All three groups were subject to random attacks by “rowdy young men and boys” who vandalized black- and Chinese-owned businesses. Because of its proximity to the mother lode, black Sacramento had a large transient male population and few religious and cultural institutions. By 1860 it claimed the only two African American doctors in the far West and its only engineer. Yet its African American residents were less wealthy and educated and far more likely to be southern-born former slaves than San Francisco blacks. The diverging trajectories of the two communities was best seen in their population increases. In 1860 San Francisco had 1,176 African Americans compared with 394 in Sacramento.18

Marysville, Grass Valley, Placerville, and Stockton were the only other cities in antebellum northern California that had any sizable black presence. Marysville and Stockton attracted ex-miners seeking permanent occupations. Many of them typically became barbers, porters, laborers, and male and female servants. Stockton, however, reflecting its importance as an agricultural community, listed a few African Americans as farmers and vaqueros. Histories of the region and era occasionally provide glimpses into community life in these towns. Marysville’s 118 African American residents in 1860 maintained a community centered on the Mount Olivet Baptist Church. Founded in 1853, the church was supported not only by parishioners but also by committees of churchwomen who conducted fund-raising “Ladies’ Festivals” featuring baked goods and knitwear popular with white residents. Similar female-organized fund-raising activities also sustained small AME churches in Placerville, Grass Valley, and Stockton.19

Black Population in Antebellum California Cities

Source: U.S. Bureau of the Census, Seventh Census of the United States, 1850 (Washington, D.C.: Robert Armstrong, Public Printer, 1853), 970–71; U.S. Bureau of the Census, Eighth Census of the United States, 1860, Population (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1864), 29–32. Governor’s Message and Report of the Secretary of State on the Census of 1852 (Sacramento: George Kerr, State Printer, 1853), 6–55.

Los Angeles had the only significant black population in southern California. Most black Angelenos were ex-slave servants brought to California by white officers during the Mexican War. Typical of this group was Peter Biggs, a former Missouri slave who became the city’s first barber and bootblack. Biggs married a Mexican woman, Juana Margarita, and during the 1860s had a monopoly on the barbering trade in this city of forty-three hundred. The small black Angeleno population also included the Owens family, which rode the post–Civil War southern California real estate boom to become the wealthiest African American family in the state by the end of the century. The Owens family saga began in Texas, where Robert Owens first earned his freedom and then worked to purchase, in turn, his wife, Minnie, and his children, Charles, Sarah Jane, and Martha. After bringing his family from Texas to Los Angeles in 1850 by an ox-drawn wagon, Robert held odd jobs and Minnie took in washing until he received a government contract to supply wood for local military installations. By 1860 the Owens family had a flourishing livery business employing ten Mexican vaqueros to break wild horses and supply cattle for sale to newly arriving settlers. The Owens homestead became the center of community life in 1854, when the family invited other blacks to attend religious services in its residence. The family reputation was enhanced when the Owenses assisted Biddy Mason’s family in its legal battle to obtain its freedom. Afterward the two families merged through marriage of the eldest children. Their descendants played prominent roles in Los Angeles’s African American community through the end of the century.20

The four statewide California Colored Conventions proved the greatest example of the political sophistication of antebellum black California. These all-male conventions, designed to present political grievances and chronicle black success, evolved out of a tradition of black collective leadership dating from the second decade of the nineteenth century, when the first national Colored Convention was held at Philadelphia in 1817. By the 1830s smaller statewide conventions were meeting in Ohio, Michigan, and Illinois. Black Californians held four conventions between 1855 and 1865. The first two were in Sacramento in 1855 and 1856. The third was held in San Francisco in 1857. Black Californians returned to Sacramento for the last Convention in 1865.21

State convention leaders, such as Henry M. Collins, Jonas Town-send, Jeremiah B. Sanderson, Frederick Barbadoes, Peter Lester, Jacob Francis, David W. Ruggles, and Mifflin W. Gibbs, had been prominent abolitionists and convention supporters before migrating to California in the 1850s. They maintained their links to the national movement by subscribing to Frederick Douglass’ Paper, and by contributing articles to that and other abolitionist journals, including the National Anti-Slavery Standard and the Pennsylvania Freeman.22

Black protest was inspired by high principle, but it also was driven by indignity and, on occasion, by physical danger. That point was made clear in an 1851 incident involving San Francisco’s leading African American business, Lester and Gibbs’s Pioneer Boot and Shoe Emporium. During an argument a white customer beat Lester with his cane and left the store without paying for a pair of boots. Since the assault occurred without white witnesses, Lester could not prosecute his attacker. The following year Mifflin Gibbs, William Newby, and Jonas Townsend organized an unsuccessful petition campaign to repeal the discriminatory sections of the testimony statute. The First State Convention of the Colored Citizens of the State of California evolved three years later from that campaign.23

Forty-nine delegates representing ten of California’s twenty-seven counties attended the convention at St. Andrews AME Church in Sacramento. Twenty-eight of them represented San Francisco and Sacramento. The other delegates spoke for Sierra, Yuba, El Dorado, Nevada, and other mother lode counties as well as San Joaquin, Contra Costa, and Santa Clara counties. Once assembled, the delegates debated the testimony prohibition. They empowered a committee to organize another petition campaign urging repeal of California’s onerous law and voted to raise twenty thousand dollars to fund the campaign. Fully conscious of their history-making gathering, Sacramento delegate Jeremiah B. Sanderson proclaimed the convention “the most important step on this side of the Continent.” After describing the accumulated wealth of black Californians, the convention called on the state’s urban African Americans to turn to farming. The convention concluded with an eloquent statement aimed at white California: “You have been wont to multiply our vices, and never to see our virtues. You call upon us to pay enormous taxes to support Government, at the same time you deny us the protection you extend to others; the security of life and property. . . . [Y]ou receive our money to educate your children, and then refuse to admit our children into the common schools. . . .” It concluded with the appeal that “justice may be meted out to all, without respect to complexion . . . and that the shield of wise, wholesome and equal laws, extend all over your great state.” Five thousand copies of the convention proceedings circulated among black Californians and their supporters.24

Two conventions followed in 1856 and 1857. While both continued to call attention to the testimony law, the 1856 convention assumed publication of Mirror of the Times as “the State Organ of the colored people of California.” It also voted a special tribute to the African American women who had organized the Mirror Association to support the fledgling newspaper. The 1857 convention, the last till 1865, condemned the U.S. Land Office’s prohibition on black homesteading of public lands and protested the exclusion of black children from public schools in rural counties. When the Democratic-controlled state legislature proved increasingly intransigent on the testimony prohibition and introduced a measure to outlaw black immigration to the state, some four hundred disillusioned black Californians (about 10 percent of the state’s population), including political leaders Mifflin Gibbs and Peter Lester, emigrated to British Columbia in 1858.25

Leland Stanford’s election in 1862 as California’s first Republican governor proved encouraging. Sensing growing popular support, San Francisco blacks created the Franchise League in 1862 to campaign for voting rights and an end to testimony restrictions. Meanwhile the Republican-dominated legislature partly obliged them by removing discriminatory barriers in education. But the crowning achievement was the elimination of the testimony restriction. In 1863 the Republican-dominated legislature repealed the antiblack provision of the testimony statute. However, it maintained the prohibition against “Indian, Mongolian, and Chinese” testimony.26

In the Civil War years California’s African Americans also challenged segregated public transportation in successful lawsuits. On May 26, 1863, San Franciscan William Bowen was ejected from a streetcar operated by the North Beach and Mission Railroad. He filed a civil suit for $10,000 in damages. The case eventually ended in district court, where on December 21, 1864, a jury awarded him $3,199 in damages. The Charlotte Brown case began a month earlier than Bowen’s on April 17, 1863, when she was ejected from a San Francisco streetcar operated by the Omnibus Company. She filed suit for $200 in damages in county court. The case first came before Judge Maurice C. Blake, who reminded the jury that California law prohibited the exclusion of blacks from streetcars. Nonetheless the jury awarded Brown five cents in damages (the cost of the fare). Three days after the trial she was again ejected from an Omnibus streetcar and once again filed suit, this time in Twelfth District Court for $3,000 in damages. Her second suit ended on January 17, 1865, when a jury awarded her $500 in damages. These victories, however, did not abolish streetcar exclusion. In 1868 the California Supreme Court reversed on appeal lower court judgments in favor of Mary E. Pleasant and Emma J. Turner, who had brought similar suits against the North Beach and Mission Railroad. The campaign for unfettered access to public transportation continued in San Francisco, as elsewhere in the West. In California black access to both public transportation and accommodations was assured only in 1893 with the enactment of an antidiscrimination law.27

When the Emancipation Proclamation took effect on January 1, 1863, local black leaders marked the event with public speeches and festivals. The black San Francisco poet James Madison Bell captured the new spirit of optimism and promise with “A Fitting Time to Celebrate,” a poem written for the occasion. After emancipation African Americans in the state’s largest city began to participate in the general community, raising hundreds of dollars for the Sanitary Fund, the forerunner of the American Red Cross, and taking part in Fourth of July celebrations.

Much of this optimism was promoted by a new newspaper, the Pacific Appeal. Founded by Philip A. Bell and Peter Anderson in 1862, the Appeal established a long tradition of journalistic activism. Bell was one of the most experienced newspaper editors and political activists in the nation when he arrived in San Francisco in 1858. A graduate of the African Free School in New York, a leading antebellum educational institution, Bell counted among his classmates the actor Ira Aldridge and the abolitionists Alexander Crummell, Henry Highland Garnet, and Samuel Ringgold Ward. After editing New York’s Weekly Advocate in 1837, he became one of four coeditors of the Colored American, the most successful African American newspaper of the period. Peter Anderson had less journalism experience but was a former correspondent for eastern black newspapers and one of the founders of Mirror of the Times. Dissatisfied with Anderson’s moderate editorial policy at the Pacific Appeal, Bell left the paper in 1865 to begin the Elevator. Although their editorial styles varied and Anderson was more politically conservative, both spoke eloquently for black Californians.28

As Civil War–inspired political changes swept through California, the state’s African American leaders organized the fourth statewide political convention at Bethel AME Church in Sacramento in October 1865. This convention, more optimistic about the African American future in the West, “devise[d] ways and means for obtaining . . . the right for elective franchise.” Invoking the specter of international concern over local discrimination, the convention called suffrage denial “unwise,” considering the soon-to-be-established trade with the “copper-colored nations of China and Japan.” Although the delegates addressed old problems, such as the exclusion of black students from rural public schools, they also urged the “colored people of the Pacific States and Territories, to secure farms and homesteads [and] to seek unsettled lands and pre-empt them, as is the right of every American citizen.” Mindful that construction would soon begin on the transcontinental railroad linking Omaha to Oakland, the convention urged the hiring of forty thousand freedmen to lay its tracks. Finally, the delegates placed black California on record as being sympathetic to “the oppressed of all nations, every race and clime,” and willing to “extend our aid to every effort to free themselves from bondage, whether it is personal servitude or political disfranchisement.” The resolution specifically mentioned the Poles and Hungarians then attempting to gain their independence from Russia and Austria. Finally, in a surprising resolution, given the rivalry between black and Irish workers, the convention declared support for the Irish independence campaign against the British Empire.29

Kansas had the only other significant concentration of free black westerners prior to 1865. Black Kansas was virtually created by the Civil War itself. The late 1850s battle for “bleeding Kansas” ended in a victory for free-state partisans. Yet the territory by 1860 attracted only 627 African Americans. By 1865, however, more than 12,000 blacks resided in Kansas, comprising 9 percent of the population. This population explosion came from a combination of politics and geography. “Free” Kansas posed an enticing destination to the large Missouri slave population.

During the 1850s Kansas attracted abolitionists, who set up Underground Railroad stations. Moreover, although only a minority of Kansas whites approved of their actions, antislavery partisans, such as James H. Lane, James Montgomery, Charles Jennison, and John Brown, who resided briefly in Kansas, led bands of Jayhawkers into Missouri in the late 1850s, raiding for slaves they escorted back across the border, creating what one historian of Missouri slavery describes as the “golden age of slave absconding.” John Brown, known primarily for the revengeful terror he inflicted on proslavery settlers in the Pottawatomie Creek massacre, is also remembered by local blacks and abolitionists for his dramatic “rescue” of eleven slaves from a Missouri plantation on Christmas Night 1858. He and his relatives concealed the women in a frontier home and the men in corn shacks for more than a month in Kansas while slave catchers searched in vain. If northern black and white abolitionists lectured against slavery and occasionally protected fugitives who fled the South, white Kansans entered a slaveholding state to rescue black men and women from bondage.30

Slaves also acted on their own, fleeing for the Kansas-Missouri border and then on to Lawrence, “the best advertised anti-slavery town in the world.” Missouri slaves learned quickly which people and places in Kansas Territory to seek out or to shun. Many fugitives sought the branch of the Underground Railroad that extended from western Missouri into Lawrence and Topeka, through Nebraska Territory, Iowa, Chicago, and finally to Canada. While Kansas abolitionists and Missouri slaveholders exaggerated the numbers of escaped slaves, clearly western Missouri, isolated from other slaveholding regions and close to free western territories, proved susceptible to servile flight.31

Opportunities for flight increased dramatically in 1861. Kansas entered the Union on January 29, 1861, barely five weeks before Lincoln’s inauguration and one month after South Carolina’s secession. The first state legislature chose two U.S. senators, one of whom, James H. Lane, was to play a crucial role in the fate of African Americans in this border region. A passionate, volatile abolitionist, Lane fused his military responsibilities and his antislavery goals. The Kansas senator envisioned a powerful slave-liberating southern expeditionary force that would march from Kansas through Indian Territory to Texas. He never completely abandoned this goal, but his immediate task, to defend Kansas from Missouri secessionists, prompted him to raise a regiment of twelve hundred troops to repulse an expected invasion by Confederate General Sterling Price. The invasion did not occur, and Lane’s forces instead marched into southwest Missouri in August 1861. News of his presence encouraged fugitive slaves to seek out his camp near Springfield. Without authorization from higher military or civilian authorities, Lane enlisted male fugitives into his command and sent the women and children to Kansas “to help save the crop and provide fuel for the winter.” This impetuous and largely symbolic act created the first African American troops in the Union army during the Civil War.32

In early September Lane dispatched his 3 chaplains to lead 218 refugees out of Missouri to Fort Scott, Kansas. The Reverend Hugh Dunn Fisher, placed in charge of the party, armed 30 black males with “almost useless guns” and sent out advance and rear scouts to warn the caravan of Confederate attack. When the refugees finally reached Kansas, Fisher ordered silence and then under “the open heavens, on the sacred soil of freedom . . . proclaimed that they were forever free.” When word of Lane’s action as a “liberator” spread, other Missouri slaves and refugees from Arkansas and Indian Territory made their way toward Kansas. In a speech before the New York Emancipation League in June 1862, Lane boasted that 5,000 fugitives from Missouri and Arkansas were in Kansas and that he had personally “aided 2,500 in their escape.” He also claimed command of 1,200 black soldiers in Kansas. Although he grossly exaggerated his impact on the black freedom, numerous fugitives sought refuge in Kansas.33

The enormous scale of the flight from slaveholding Missouri becomes evident when one examines the slave population statistics for the period. Between 1860 and 1863 Missouri’s slaves declined from 114,931 to 73,811. Some Missouri slaveholders sent or carried their slaves south to Arkansas, Indian Territory, and Texas. Other slaves fled across the Mississippi River to Illinois or north to Iowa. But many of them made the perilous dash west. Henry Clay Bruce, the brother of future Mississippi Senator Blanche K. Bruce, recounted in his autobiography how he and his fiancee escaped from Missouri to Kansas in 1863. Bruce strapped around his waist “a pair of Colt’s revolvers and plenty of ammunition” for the run to the western border. “We avoided the main road and made the entire trip . . . without meeting anyone. . . . We crossed the Missouri River on a ferry boat to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. I then felt myself a free man.”34

The Civil War influx swelled the state’s black population to 12,527 in 1865. The migrants concentrated in three counties, Leavenworth, Douglas, and Wyandotte, which had 56 percent of the total black population. Moreover, two Kansas towns—Leavenworth with 2,400 blacks, and Lawrence with nearly 1,000—contained 72 percent of the state’s urban black population. From the beginning of the war Senator Lane and other abolitionists envisioned an exchange of black labor for black freedom. The fugitive slaves who arrived in the state were dispersed through rural counties to cultivate and harvest crops. Very little machinery was available to grow wheat, a principal crop in the 1860s, and since most white males were in the Federal army, black laborers were especially welcomed and were credited with producing the bountiful harvest of 1863. The Fort Scott Bulletin in 1862 observed that almost every farm in the Neosho River valley “was supplied with labor in the shape of a good healthy thousand dollar Contraband, to do the work while the husbands, fathers and brothers are doing the fighting.” Even Senator Lane employed former slaves to grow cotton on his Douglas County farm.35

Other refugees depended upon work and charity in towns and cities. John B. Wood of Lawrence wrote Boston abolitionist George L. Stearns in November 1861, warning that the thousands of black wheat field workers would soon be unemployed and sure to gather in Lawrence. Fearing their plight would overwhelm the town, Wood requested financial assistance from the “friends of humanity at the East,” to feed and clothe the ex-slaves. Wood’s fears proved groundless. Most of the migrants found or created work, and thus, according to Richard Cordley, “very few, if any of them, became objects of charity.”36

If most Lawrence blacks avoided charity, the type of work they performed and the skills they brought from their slave experience guaranteed that they were never far from that condition. The state census of 1865 showed 349 employed blacks in Lawrence. Of these, 95 men were listed as soldiers, while 85 were day laborers, the second largest occupational category. Of the 92 female workers, 49 were domestics, 27 were washerwomen, and 7 worked as housekeepers, 6 as servants and 3 as cooks. Thus 177 blacks, half of the town’s total, worked as unskilled laborers. Of the one-fifth who were skilled, 23 were teamsters, 8 were blacksmiths, and 4 barbers. Lawrence also had 1 black saloonkeeper, 1 carpenter, 1 shoemaker, 1 printer, and 1 preacher.37

After 1862 Lawrence’s residents began to recognize a permanent black settlement. “The Negroes are not coming. They are here. They will stay here,” asserted abolitionist Richard Cordley, “They are to be our neighbors, whatever we may think about it, whatever we may do about it.” White Lawrence citizens supported efforts to teach ex-slaves literacy. While black children attended public schools during the day, adults joined a night school that met for two hours five nights a week. Classes were taught by volunteer teachers, including future Mississippi Senator Blanche K. Bruce, who instructed approximately 125 pupils. The refugees themselves founded Freedmen’s Church on September 28, 1862. The first black church in Lawrence was described as a “comfortable brick [building] . . . filled with an attentive congregation of ‘freedmen’—all lately from bondage, and all neatly dressed as a result of their short experience of free labor.”38

Leavenworth, the oldest and largest Civil War–era Kansas town, also had a sizable African American population, 2,455 in 1865, 16 percent of the population. Like most black newcomers to Kansas, Leavenworth’s African Americans were mostly fugitives who had arrived “wholly destitute of the means of living.” Leavenworth’s civic leaders met with members of the First Colored Baptist Church in February 1862, to “take into consideration measures for the amelioration of the condition of the colored people. . . .” Whites at that meeting included Colonel Daniel R. Anthony (brother of women’s suffrage advocate Susan B. Anthony), Dr. R. C. Anderson, and Richard J. Hinton, a prominent abolitionist and journalist. African American community leaders included the Reverend Robert Caldwell of the Baptist Church, Lewis Overton, a teacher in a black community-sponsored school, and William Mathews, destined to become one of the first black officers in the Union army. Hinton proposed the founding of the Kansas Emancipation League, whose object was to “assist all efforts to destroy slavery” and to provide help for the freedpeople arriving in the Leavenworth area.39

Leavenworth African Americans found employment in a variety of occupations. Some worked on farms during the spring and summer, but a much larger number were employed as teamsters, hotel waiters, porters, cooks, maids, and manual laborers. The Emancipation League’s Labor Exchange and Intelligence Office, in Dr. R. C. Anderson’s drugstore, became an informal employment agency for local blacks. Yet the rapid influx of fugitive slaves, their few skills, and the small size of the town ensured that their employment prospects remained circumscribed. From 1862 to 1865 the Emancipation League, the Baptist Church, and interested black and white individuals continued to provide support for the fugitives.40

Not all black Kansans welcomed the ex-slaves. Freeborn blacks in Leavenworth derisively termed the Missourians “contrabands,” and by 1865 they were attempting to exclude the wartime migrants from their organizations and social circles. Ex-slave ministers Jesse Mills and Moses White were denied permanent churches in Kansas even though both were able preachers and White had founded the African Methodist Episcopal Church in Leavenworth. Yet since the newcomers were the overwhelming majority of the population, they supplanted the political and social leadership of the tiny prewar population. African American women in Lawrence organized the Ladies Refugee Aid Society to collect food, clothing, and money and to assist destitute ex-slaves. The society foreshadowed the Kansas Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs and provided a model for self-help activities that extended well into the twentieth century.41

“Soldiering” led all occupations among black males in Lawrence, Leavenworth, and the rest of the state. The reason is readily apparent. Fugitive slaves saw the Civil War as a struggle for emancipation. Many wanted a role in freeing relatives and friends who remained behind. Western Union army commanders had few reservations about recruiting and incorporating black or Indian soldiers. Senator James Lane set the tone in a speech in Leavenworth in January 1862, declaring that “if negroes attached to his army secured guns, he did not intend to punish them for killing ‘traitors.’ “Official support for recruiting black soldiers in Kansas came in July 1862, when Brigadier General James G. Blunt, a Lane political ally and the commander of the Department of Kansas, wrote to Colonel William Weer, authorizing him to accept “all persons, without reference to color,” who were “willing to fight for the American flag . . . and the Federal Government.” Thirty-five-year-old Blunt, a former frontier doctor and abolitionist, had helped John Brown spirit slaves to Canada. He seized the opportunity to make the military contest in the West a war for black liberation. The following month Lane informed Secretary of War Edwin Stanton that the state would furnish two regiments of black soldiers.42

Lane presented a carefully crafted public image as a courageous leader dedicated to black liberation much like his hero, John Brown. But Lane in fact exhibited a callous disregard for the people he vowed to free from bondage. Arriving at Leavenworth on August 3, 1862, he announced that all able-bodied African American males between the ages of eighteen and forty-five could join the First Kansas Colored Infantry Regiment of the “Liberating Army.” He called for a thousand volunteers at a black mass meeting and then added, “We have been saying that you would fight, and if you won’t, we will make you.” Moreover, Lane ignored charges that his recruiters “unlawfully restrained persons of their liberty” and paid cash bonuses for seized Missouri slaves who were delivered to Kansas recruiting stations.43

Such practices continued even after Lee’s surrender at Appomattox. In June 1865 Captain H. Ford Douglas, the highest-ranking African American officer in Kansas, took the extraordinary step of requesting that the Kansas Independent Battery of the U.S. Colored Light Artillery under his command be immediately mustered out of service. Douglas told of black Kansans being beaten and dragged from their wives and children in midwinter, starved until sheer exhaustion, and then compelled to join the U.S. Army. Seventy-five percent of the men under his command that June were “victims of a cruel and shameless conscription . . . in opposition to all civil and military law.” Following an investigation by the War Department, the men were mustered out on July 22, 1865.44

Most African Americans, however, eagerly fought against the Confederacy. Senator Lane promised ten dollars per month as well as “good” quarters, rations, and clothing. In addition to the pay and provisions, certificates of freedom were issued to each black enlistee and his immediate family. By September 12, 1862, the “colored” regiment was six hundred strong. Captain George J. Martin reported that “the men learn [ed] their duties with great ease and rapidity” and were “delighted with the prospect of fighting for their freedom.” On October 17, 1862, the First Kansas Colored Infantry was organized near Fort Lincoln in Bourbon County.45

The First Kansas Colored was soon sent to secure Federal control of the northeastern part of Indian Territory. The regiment became part of the Army of the Frontier, a unit remarkable in the annals of U.S. military history. This triracial force of three thousand soldiers included loyal Indian regiments, white regiments from the western states and territories, and now the First Kansas Colored. While stationed in Indian Territory, the First Kansas Colored undertook a number of military assignments. It fought Confederate guerrilla leader Colonel William C. Quantrill in 1863 and the following year faced Colonel Stand Watie, the Cherokee commander of Confederate Indian forces. The regiment suffered a humiliating defeat at the hands of Confederates at Flat Rock in September 1864.46

On July 17, 1863, the First Kansas Colored fought in the largest single Civil War engagement in Indian Territory, the Battle of Honey Springs. Confederate troops, eager to drive Union occupying forces from Indian Territory, launched an attack on the Federal lines at Honey Springs. Posted in shoulder-high prairie grass, 500 black soldiers, flanked on each side by Cherokee Indian and dismounted white Colorado cavalry units, held the crucial center of the Union line. Arrayed against this forward position of the Army of the Frontier were 6,000 Confederates. The battle commenced with a dawn artillery exchange, followed at 10:00 A.M. by an order for Union forces to advance. Confederate artillery bombarded the advancing troops, particularly the First Kansas Colored, “tearing huge gaps in the Union line.” Nonetheless Union units advanced until forty yards from the Confederate front line held by the Twenty-ninth Texas Infantry. Then Union and Confederate troops fired simultaneous volleys. Thinking the Union forces had retreated after the initial volley, Confederate commander Charles DeMorse ordered his troops to charge the Union lines, which fired another volley. The “first rank of the Twenty-ninth simply disappeared,” and the remaining Confederate troops retreated. After the battle the First Kansas Colored soldiers discovered strewn among the abandoned Confederate supplies shackles that were to be used to chain the captured black soldiers. Eight days after the Battle of Honey Springs, General Blunt wrote in his report that the soldiers of the First Kansas Colored Regiment “fought like veterans, with a coolness and valor that is unsurpassed. They preserved their line perfect throughout the whole engagement and, although in the hottest of the fight, they never once faltered.” By June 1863 a second Kansas “colored” regiment had been formed under Colonel Samuel J. Crawford, a future governor of the state. The Lane and Crawford regiments and a smaller brigade brought together 2,083 African American men for the Union cause, one-sixth of the African American population in Kansas in 1865.47

In October 1863 twenty-three delegates representing approximately seven thousand black Kansans gathered in Leavenworth for the first Kansas State Colored Convention. Most delegates, and the people they represented, had been in Kansas less than three years. Nonetheless they pledged their future to Kansas. The delegates praised the help black Kansans received from sympathetic whites but then called for more self-reliance. “It does not follow, because so much is being done for us, that we can do nothing for ourselves.” They called for universal male suffrage, access to public education, and federal pay for soldiers of the First Kansas Colored Regiment for their time in the army before January 1863. The convention opposed colonization of blacks abroad and urged the new Kansans to become farmers. It reiterated the necessity of black suffrage “. . . as in architecture, that building is most secure whose base is broadest, so in politics, that government is most permanent, whose base rests on the broadest foundations of liberty and justice.” Finally it declared to white Kansas “our misery is not necessary to your happiness. . . . Your rights can never be secure whilst ours are denied.”48

The October meeting was the first of a series of annual conventions of African American Kansans. Subsequent gatherings agitated for an amendment to the Kansas Constitution to guarantee black male voting rights. Black Kansans also demanded the right to serve in the state militia and on juries and called for an end to discriminatory practices in public transportation and public accommodations, initiating a century-long struggle to extend the prewar promise of freedom for slaves into the post–Civil War prospect of equal rights for all of the state’s citizens.49

Voluntary pre–Civil War black migration was limited by slavery, which held 90 percent of African Americans in its grip. It was also discouraged by discriminatory legislation in California, Oregon, Kansas, and most western territories. However, the Thirteenth Amendment, which terminated slavery in 1865, also opened the West to tens of thousands of African American emigrants. They and their descendants were to place a profound social and cultural imprint on the region.