In February 1863, while the eastern United States fought the Civil War and the Emancipation Proclamation was less than two months old, Peter Anderson wrote an editorial in the Pacific Appeal that fused the destiny of the ex-slaves with the West. Anderson called on “our leading men in the east” to initiate a “system of land speculation west of Kansas, or in any of the Territories, and endeavor to infuse into the minds of these freedmen the importance of agriculture, that they may become producers. By this means they can come up with the expected growth of the Great West. . . .”1

Anderson envisioned a great march of freedpeople westward, urged on by “our leading men in the east,” the federal government, and “our white friends who have been battling in the cause of freedom.” But the great march did not come. Most freedpeople in the late 1860s saw their destiny in an economically and politically “reconstructed” South. The promise was so alluring that it briefly drew some westerners back East. San Francisco minister John Jamison Moore, former Mirror of the Times editor Jonas H. Townsend, and Mifflin W. Gibbs, British Columbia’s first black officeholder, all moved to the South, casting their lot with the freedpeople. Their return prompted another San Francisco editor, Philip A. Bell, of the Elevator, to conclude in 1868: “The tide of travel is reversed. Our representative men are leaving us, going East, some never to return.”2

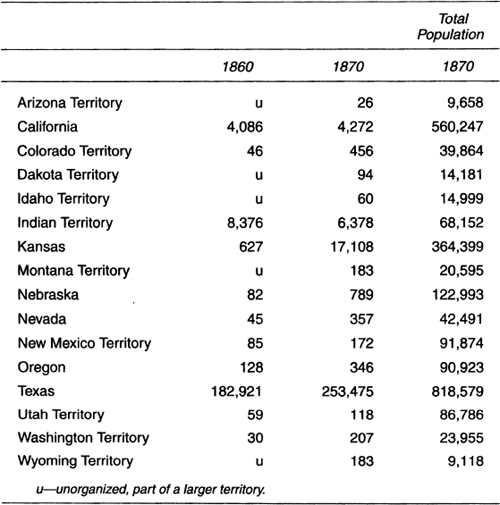

The African American Population in Western States and Territories, 1860–70

Sources: U.S. Bureau of the Census, Negro Population in the United States, 1790–1915 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1918), 43, 44; U.S. Bureau of the Census, Statistics of the Population of the United States, 1870 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1872), 3.

Bell proved as wrong as Anderson, for a steady trickle of blacks pushed westward. By 1870, 284,000 African Americans lived in the sixteen states and territories of the region and comprised 12 percent of the total population. The great concentrations were in Texas and Indian Territory, the major antebellum slaveholding areas. California and Kansas were the only other states with more than 4,000 black residents. Caution must be used in interpreting low figures elsewhere in the West. Blacks avoided some places, anticipating scant economic opportunity. Few African Americans, for example, migrated to Idaho and the Dakotas during this period, and the nineteenth-century African American population of Nevada peaked at 488 in 1880 and declined to 134 during the next two decades.3

Before the West could become secure for African American settlement, the various states and territories had to extend political rights to African Americans. The debate over those rights lasted from the end of the Civil War to the enactment of the Fifteenth Amendment in 1870. Reconstruction thus became not simply a conflict between the federal government and ex-Confederate states over their restoration to the Union but a larger national debate over the relationship between federal and state power.4

Black westerners paid attention to Reconstruction. They were understandably anxious that Reconstruction in the ex-Confederate states ensure suffrage and civil rights for the ex-slaves, but they also understood their own political disabilities. Denial of the rights to vote and to serve in the militia; exclusion from public schools, the jury box, and public transportation and accommodations; and prohibition of interracial marriages were painful reminders of the limitations on black freedom in the West. Thus Reconstruction meant black westerners’ obtaining full citizenship within their states and territories.5

Despite a history of antiblack legislation in the West, by the 1860s some Euro-Americans began to speak on behalf of African American rights. John Martin, editor of the Atchison (Kansas) Champion, wrote in January 1865: “Give the negro a chance to make a man of himself. . . . Treat him as a human being and he will quickly assert by his own capacities and exertions his right to be regarded as one.” Occasionally attitudes changed. Jesse Applegate of Oregon reminded Federal Judge Matthew P. Deady in 1865 that “it is not right to indulge prejudices of creed or race. . . .” Recalling Deady’s prominent role in instituting Oregon’s 1857 black exclusion clause, Applegate believed the judge had become a “wiser and better man” in abandoning his prejudices regarding blacks.6

Post–Civil War Texas, however, remained closer to the old South than the New West. Union General Gordon Granger’s occupation force of eighteen hundred soldiers reached Galveston on June 19, 1865, initiating Texas Reconstruction. Granger immediately issued General Order No. 3, the Texas emancipation proclamation, which established “an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves.” However, he advised the freedpeople to sign labor contracts and remain with their old masters.7

Shortly after General Granger’s proclamation, the Freedmen’s Bureau was organized in Texas to assist ex-slaves in adjusting to their new legal and social status. Education for the freedpeople led the way. By 1870 forty-six bureau-sponsored schools were operating in the state, with the largest of these in Galveston, Houston, San Antonio, and Brownsville. The bureau reported 5,182 black pupils were attending those schools, compared with only 11 African American children enrolled in schools throughout the entire state ten years earlier.8

Emancipation fueled every emotion. Some former slaves, such as the people set free on the James Davis plantation in San Jacinto County, were disoriented and confused. “There was lots of crying and weeping,” reported one ex-slave observer, “because they knew nothing and had nowhere to go.” To others emancipation meant “no more whippings.” After the local sheriff read Granger’s proclamation in Austin, Harriet, a domestic slave, thinking more of her new baby’s changed status than her own, ran home to her child and threw her in the air, crying “Tamar, you are free.”9

Numerous slaves tested their freedom by leaving east Texas and Gulf Coast plantations. Some, brought to the state during the Civil War, immediately headed eastward, hoping to reunite with family members in the Old South. Others moved to Galveston, Houston, Austin, San Antonio, and other Texas cities. As one ex-slave remarked, they wanted “to get closer to freedom, so they’d know what it was—like a place or a city.” Many ex-slaves sought out the cities because federal garrisons there offered protection from the racist violence that continued from emancipation until the end of the century.10

Many slaves were driven off plantations by angry landowners. Often such actions were taken in concert as dozens of planters in a county sought to punish the blacks for their freedom. In the fall of 1865 white citizens in Freestone County, for example, resolved to hire no blacks and to whip any freedman who tried to sign a labor contract with a white employer. Whites who violated the resolution were to be warned on the first offense and whipped or hanged on the second. Other owners were so disturbed by emancipation that they poisoned water wells or shot slaves who persisted in proclaiming their freedom. When future Texas Governor Oran M. Roberts called for the colonization of the freedpeople in west Texas, one Houston newspaper disingenuously argued that placing blacks among the Comanche and Apache, “the most savage of all the savages of America, [would] excite among them the most relentless fury. . . . It pleases us amazingly.” Such extreme measures went against the economic interests of white employers as well as ex-slaves, but they indicated ex-Confederate resistance to the postwar political order.11

As in the Old South, moves to maintain white supremacy came long before the elected Reconstruction government of white and black Unionists assumed power in 1870. Ex-Confederates dominated the 1866 constitutional convention called to reestablish state government. Emboldened by President Johnson’s lenient reconstruction policies, the convention accepted the end of slavery but not black suffrage. Instead it restricted black legal testimony, required racially segregated schools, called for dismantling the Freedmen’s Bureau, and repudiated the recently enacted Civil Rights Act.12

The first postconvention legislature added railroad passenger segregation and black exclusion from service on juries or public officeholding. Reflecting the frontier status of much of the state, the legislature also enacted a “whites only” Texas Homestead Act that granted up to 160 acres of free land in west Texas. This measure alone did not prevent blacks from buying land, but coupled with the widespread opposition to land sales to the freedpeople, it froze most ex-slaves into a landless peasantry.13

However, the black codes enacted by this legislature constituted the cornerstone of the postwar social order orchestrated by the ex-Confederates. One code, a child apprenticeship law, allowed white employers to control the labor of black children until they were twenty-one or married. The contract labor code bound entire families to their employers, who could impose fines on any worker guilty of disobedience or unapproved absence. In fact laborers who missed three days of work forfeited an entire year’s wages. Texas, like other ex-Confederate states, promulgated a vagrancy law to pressure blacks into accepting labor contracts. Another law established Texas’s notorious convict leasing system. Those serving time in city or county jails for petty crimes could be hired out to railroads, iron foundries, ore mines, and public utilities. When a northern newspaper correspondent asked a white Texan if using prison labor to build a railroad through Rusk County was a safe practice, he was assured, “Of course, [the prisoners] haven’t done anything very bad.” The Texan’s reassurances were all too accurate. At that time one black male convict was serving three years for stealing a twenty-five-cent can of sardines.14

The Texas black codes and similar measures in other ex-Confederate states generated a backlash in the North. Union objectives won on the battlefield were about to be sacrificed in the effort to reestablish civilian government in the South. Consequently northern voters in 1866 elected a huge Republican majority that halted temporarily the racial caste system evolving in Texas and other ex-Confederate states. In March 1867 Congress passed the first of three Reconstruction Acts. It divided the ex-Confederate states into five military districts and returned civil government to provisional status subject to military command. Each state was now required to call a new constitutional convention to be elected by all eligible male voters. The other acts denied voting rights to ranking ex-Confederates and stipulated that commanding generals supervise voter registration. The commanders were empowered to remove or suspend anyone in state government who blocked federal programs. Angry ex-Confederates and their sympathizers soon stepped up their campaign of terror and economic intimidation while white Unionists and newly enfranchised blacks moved to participate in a more democratic government.

Heeding a call from Texas Unionists, approximately 20 white and 150 black delegates met in Houston on July 4, 1867, to form the Texas Republican party. They selected Elisha M. Pease as chairman. Later that month Pease was appointed provisional governor of Texas after General Philip Sheridan, the regional military commander, removed Governor James Throckmorton. In 1868 another constitutional convention met this time with African Americans constituting 10 of the 90 delegates. For a brief period in the early 1870s black Texans had a strong voice in state government. They were led by decidedly different politicians, George T. Ruby of Galveston and Matthew Gaines of Washington County, who were elected to the state senate in 1869. Ruby and Gaines were the highest-ranking black elected officials in Texas during Reconstruction.

George Thompson Ruby, a freeborn native of New York City, had been educated in Maine. Prior to the Civil War he worked in Boston as a correspondent for the Pine and Palm, a newspaper edited by the British abolitionist James Redpath. Ruby spent two years (1860–62) in Haiti as part of Redpath’s short-lived effort to promote African American immigration to that Caribbean nation. He returned to the United States, arriving in Louisiana shortly after Union forces occupied New Orleans. Ruby served as a schoolteacher for the freedpeople for the next four years before moving to Texas in 1866 to become the Freedmen’s Bureau agent for Galveston. There he edited a newspaper, the Freedman, which appeared intermittently in Galveston and Austin. Ruby, as president of the Galveston Union League and the Colored National Labor Convention, a black Galveston dockworkers’ union, built a formidable political organization. He also aligned with white Unionist Edmund J. Davis, the first elected governor under the new constitution. Ruby remained a Davis confidant and supporter even when other African American politicians began to question the governor’s commitment to equal rights. Young, educated, articulate, ambitious, Ruby exhibited all the characteristics Texas conservatives most feared Reconstruction would produce in the freedpeople.15

Matthew Gaines, in contrast, spoke for the rural freedpeople. Born a slave in Louisiana around 1840, Gaines was sold to a Robertson County cotton planter in 1859. In 1863 Gaines attempted an escape to Mexico. Working his way west, he arrived at Fort McKavett, an abandoned frontier outpost in Menard County, where he was captured by Texas Rangers. Inexplicably, Gaines was not returned to Robertson County and instead worked as a blacksmith and sheep-herder in west Texas for the remainder of the war. By 1866, however, he had moved back to Texas plantation country, settling in Washington County. By 1869 Gaines had become both a minister and a Republican party activist when he was elected to the Texas senate.16

Gaines soon developed in the senate what his biographer called a “critical, emotional and apocalyptic style” in politics. During an era when partisan political loyalty was revered, Gaines challenged fellow Republicans, including his colleague George T. Ruby, as easily as Democrats. When the legislature proposed a bureau of immigration to encourage settlers from the northern United States, western Europe, and Great Britain, Gaines offered an amendment to dispatch agents to Africa. His amendment was voted down, eighteen to four, with Ruby among its opponents. When conservative legislators opposed creation of a state police force to address the rampant political violence against the freedpeople, Gaines declared on the floor of the senate, “It is not so much the idea of placing . . . great power in the hands of the [governor] but the idea of gentlemen of my color being armed and riding around after desperados.” He again broke ranks with many of his black and white colleagues when he called for integrated public schools. After listening to days of attacks by Democrats and some Republicans, an exasperated Gaines, directing his comments at the opponents, said if they objected to whites sitting next to blacks, they should resign their posts in the legislature and go home. He then added, “They talk about separating them. It can’t be done . . . my children have the right to sit by the best man’s daughter in the land.”17

Texas had the third-smallest black population of the former Confederate states, a fact reflected in the state legislature. The 14 blacks who served in 1870–71 were the largest number elected during the nineteenth century. Black Texans made up 30 percent of the state’s population, but they never exceeded 12 percent of the 120-member legislature. Thus Radical Reconstruction programs depended on the partnership of white Unionists and newly enfranchised black voters. Radical Unionists, primarily from the western part of the state, followed Edmund Davis of Corpus Christi, who formed a unit of Texas Union cavalry during the Civil War and in 1870 gave Texas its only elected Republican administration of the nineteenth century.18

Conservatives abhorred Texas Unionists such as Davis, whom they deemed responsible for the “antiwhite” politics of the Reconstruction era. Yet Texas Unionists never agreed on black political participation and civil rights. Few wanted to exclude all black voters, but some, such as Andrew Jackson Hamilton, clearly wanted restrictions placed on African American suffrage. Other Unionists, including Davis, and German immigrants, such as Edward Degener, Julius Schutz, and Louis Constant, pushed for full rights for the ex-slaves. Yet most white citizens of the state viewed such activities by fellow white Texans as racial treason. Little wonder that during the gubernatorial election of 1869 the San Antonio Daily Herald openly wished Davis and Ruby hanged. “Oh, what a happy pair they would be, upon a tree together.”19

When conservatives boycotted the election of delegates to the 1868 constitutional convention and the 1869 gubernatorial election, black and white Unionists temporarily dominated Texas politics. George Ruby and Matt Gaines went to the state senate, and twelve African American men gained seats in the house of representatives. By 1898 forty-two black men had served in that body at different times. African American politicians assumed other offices as well. Walter Burton, who served four terms in the state senate in the 1880s, was twice elected sheriff of Fort Bend County between 1869 and 1874. Matt Kilpatrick was elected treasurer of Waller County. Norris Wright Cuney, who never ran for a major political office, nonetheless led the Texas Republican party from Edmund Davis’s death in 1883 until 1896.20

Despite a Republican majority, Texas’s first interracial legislature failed to repeal the black codes. Moderate Republicans joined Democrats to maintain most contract labor provisions, the convict labor system, the vagrancy statute, and the child apprenticeship law. Practically, however, these laws became moot as planters and freedpeople increasingly adopted sharecropping and tenancy, thus eliminating the landowner’s need to “control” black labor. The new legislature ratified the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, outlawed bribery or intimidation of voters, prohibited discrimination on public transportation, centralized (but did not desegregate) the public schools, passed a gun control law, reestablished the state militia, and organized the Texas State Police. Directly under the governor’s control, this mounted police force was authorized to pursue criminals across county lines and to arrest offenders in those counties where “authorities [were] too weak to enforce respect, or indisposed to do so.” Freedmen constituted a majority of the 3,500-man militia. The 257-member state police included whites and Mexican Americans but was 40 percent black.21

The state police, however, could not prevent the reign of Reconstruction-era terror in the state. The Texas Ku Klux Klan murdered numerous freedmen, including former state legislator Goldstein Dupree, who was killed in 1873 while campaigning for the reelection of Governor Davis. Antiblack violence was exacerbated by a frontier mentality, if not frontier conditions, which condoned settling disputes by force. Moreover, a highly romanticized “social banditry” rising from antipathy toward the Davis administration and toward freedpeople spawned unusually callous violence. When a Red River County Freedmen’s Bureau agent asserted that whites killed blacks “for the love of killing,” he described a one-sided racial war that engulfed Texas for the rest of the century. Whites killed blacks for celebrating their emancipation, for refusing to remove their hats when whites passed, for refusing to be whipped, for improperly addressing a white man, and “to see them kick.” The sheriff of De Witt County shot a black man who whistled “Yankee Doodle.” Some Texas outlaws, including a Limestone County desperado known only as Dixie and the infamous John Wesley Hardin, who bragged in his autobiography about his killing of several black state policemen, were often shielded from authorities by sympathetic whites. Ignoring the potential consequences, some freedmen defended themselves against these outlaws. Merrick Trammell, for example, killed the notorious Dixie and gained Limestone County a respite from the terror campaign.22

Despite both the violence and discriminatory legislation, freedpeople in Texas created lives independent of the shadow of slavery. The U.S. Congress legalized slave marriages in March 1865. After Union occupation began three months later, thousands of Texas women and men who had lived together during slavery, gained an important measure of self-respect when their marriages were formally recognized. Moreover, after 1865 thousands of other couples obtained licenses and took vows in civil or religious ceremonies to establish or renew their commitments. Other freedpeople attempted to reunite families separated during slavery, with some black Texans travelling as far as South Carolina and California to retrieve their children. Census figures in 1870 confirm the desire of freedpeople to maintain families. Whether in such cities as Galveston, Austin, and Houston or such rural counties as Matagorda, Fayette, and Grayson, black marriage ratios ran only slightly behind those of whites. In Fayette County, for example, 90 percent of the households included husband and wife in comparison to 96 percent for Anglos.23

Postwar black Texans also asserted their new freedom by founding churches. Soon after emancipation black Texans voluntarily withdrew from white churches, partly to escape prejudice and partly to control their own institutions. Black Baptists in Waco in 1866 created the New Hope Baptist Church, which first met in an abandoned foundry. In the same year, the first Methodist Church of Austin lost its black members, when the latter created the Austin Methodist Episcopal Church. By 1870 at least 150 black churches operated in the state, and the numbers increased dramatically during the rest of the century. As one historian describes it, church separation “represented as much an assertion of freedom as the practice of leaving the old plantation.”24

Black churches were usually the first institutions in the emerging African American communities. They were places of worship and community centers, where social events, political meetings, and sporting events took place. Churches in Galveston, Houston, and Corpus Christi also served as sites for the first Freedmen’s Bureau schools in the state. The long relationship between the state’s African American churches and colleges was established during this period when the African Methodist Episcopal Church Conference established Paul Quinn College in Austin in 1872 (it moved to Waco in 1881). In 1873 the Methodist Episcopal Church established Wiley College in Marshall. However, Tillotson College of Austin, the oldest black college in the state, was founded in 1867 by the racially integrated Congregational Church.25

Often black churches were the anchors of distinct African American neighborhoods. As freedpeople flocked to dozens of communities, usually called freedman towns, across the state, they created shantytowns usually on the edges of established communities. Austin had two post–Civil War black communities. The first, Pleasant Hill, was an impoverished area of shacks and tents founded in 1865. By the early 1870s ex-slave Griffin Clark had developed Clarksville, which became a segregated enclave in West Austin. With the help of former Texas Governor Elisha M. Pease, these freedpeople built or purchased homes and created a village separate from white Austin. The voluntary separation often expressed in the creation of independent black churches and in distinct neighborhoods occasionally extended to separate communities. By 1875 black Texans had created thirty-nine separate towns and villages in fifteen Texas counties to escape white political and economic control. Kendleton in Fort Bend County, Shankleville in Newton County, and Board House in Blanco County all attested to their desire to give lasting meaning to the concept of emancipation.26

Texas’s brief interlude of interracial democracy began to crumble in 1872, when conservative Democrats regained control of the state legislature. The Democrats immediately abolished the Texas State Police over Governor Davis’s veto, replacing it with the all-white Texas Rangers, until then primarily a frontier and border defense force. Moreover, the Democrats denied the governor the authority to declare martial law. The following year Davis was defeated in the gubernatorial election by ex-Confederate Richard Coke, and the freedpeople lost their major political ally in the effort to democratize Texas government. Conservatives in 1875 wrote a new constitution that, although acknowledging black suffrage, included measures that reestablished white supremacy. Yet reimposed white rule could not entirely erase the progress black Texans had made in creating their own institutions, in gaining access to education, and in asserting in crucial ways their dignity and self-worth. Building upon that foundation, they were to sustain a growing campaign that in the twentieth century successfully challenged their status as second-class citizens.27

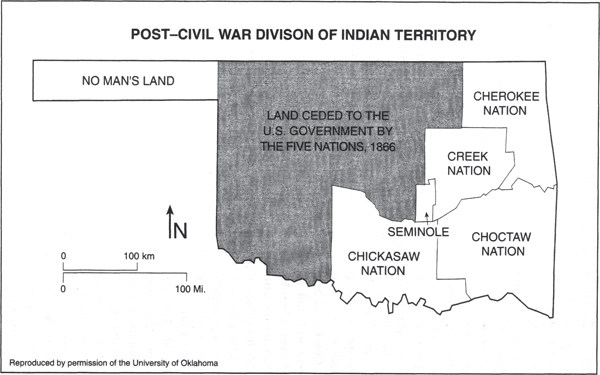

Reconstruction in Indian Territory, the home of the Cherokee, Creek, Choctaw, Cherokee, and Seminole people, also occurred against a backdrop of heightened tension between Native Americans and their ex-slaves. Yet Reconstruction in Indian Territory also set in motion the process by which both Native Americans and African Americans became politically marginalized in the Five Nations by the end of the nineteenth century.

The federal government reallocated land from Indians to the freedpeople, a crucial reform that it was unable or unwilling to require in the states of the former Confederacy. Each tribe was required to relinquish control of the sparsely settled portions of its lands west of the ninety-eighth meridian. This region, eventually called Oklahoma Territory, was opened to settlement by other Indian tribes and, in 1889, to non-Indians. Moreover, the nations were compelled to grant rights-of-way to railroad companies crossing their lands, a concession that exposed Indian Territory to successive waves of uninvited outsiders.28

The genesis of this policy can be traced to the report of Union officer John Sanborn. In October 1865 Congress appointed Brevet Major General John Sanborn special commissioner to investigate conditions among the freedpeople in Indian Territory. Sanborn visited every nation between November 1865 and April 1866. He reported to Congress that both the Indians and the freedpeople were eager for the ex-slaves to remain in the territory but “upon a tract of country by themselves.” He urged that such a tract, “large enough to give a square mile to every four persons,” be set aside and that it “should be the most fertile in the territory as the freedmen are the principal producers.” Anticipating opposition from the nations, Sanborn called on the federal government to grant the land quickly and resolutely. “When the tribes know that this policy is determined upon by the government,” he argued, “they will submit to it without any open resistance . . . and the freedmen will rejoice that . . . they have a prospect of a permanent home for themselves and their children.”29

Sanborn also reported Indian sentiment toward the freedpeople. The Seminole and Creek favored incorporation of their former slaves into their tribes, the Cherokee were divided on the issue, and the Chickasaw and Choctaw exhibited “a violent prejudice” toward their freedpeople, punctuated by assaults and murders. The Chickasaw, for example, would not permit any freedman who had joined the Union army to return to the nation. Sanborn concluded that since a “large portion of the [Chickasaw and Choctaw] people [did] not admit any change” from the prewar status of masters and slaves, the government had to place federal troops in the two nations to protect the freedpeople.30

Sanborn’s report predicted the course of Reconstruction in the Indian nations. Citing widespread Indian support of the Confederacy, the U.S. government nullified all previous treaties with the Five Nations. New treaties negotiated in 1866 abolished slavery, required the tribes to cede the western half of their lands to the federal government, and called for reorganized tribal governments. After emancipation the government allowed each nation to decide individually if, and in what manner, it would incorporate the freedpeople. Creek and Seminole Indians made their former slaves tribal citizens with full civil and political rights. Tribal emancipation in 1863 freed Cherokee slaves, but only those who lived in the nation in 1866 or who returned within six months of the treaty signing were eligible for citizenship. Consequently some Cherokee slaves who had fled during the war but returned after 1867 were declared “intruders,” even though they might be husbands, wives, children, and parents of Cherokee citizens.31

The Choctaw and Chickasaw argued that none of the former slaveholders of the Confederacy had been compelled to share their land or other property with their ex-slaves. Thus they refused to incorporate their freedpeople or take back those who had fled the nations during the war. Instead they enacted black codes to regulate the labor and behavior of the ex-slaves, including a vagrancy act that allowed the local sheriff to arrest and hire out to the highest bidder any ex-slave found moving about without a job. Moreover, for a brief period in the 1860s the Choctaw and Chickasaw mounted a campaign of terror to drive out unwanted Texas ex-slaves who settled on tribal lands. Indian vigilantes seized and whipped blacks not known in the area, destroyed their settlements, and forced most of them to flee the nations.32

In 1870 Indian Territory had 68,152 residents. Native Americans constituted 87 percent of the population, while 6,378 blacks and 2,407 whites made up the remainder. The 6,000 African Americans were fewer than the 8,000 counted ten years earlier. However, some freedpeople from neighboring states had settled in Indian Territory without authorization. In 1868 Chickasaw officials bitterly complained of former black soldiers from the United States residing illegally in the western section of their nation.33 Yet most African Americans in the territory in 1870 were former slaves of the various Indian nations. Their fate was determined by the actions of individual Indian nations and the federal government.

All five tribes extended certain privileges, and each allocated farmland. As Sanborn had urged in 1866, Creek and Seminole ex-slaves received allotments along the river bottoms—choice parcels for cotton production. Theoretically the new tribal constitutions guaranteed freedpeople the protection of person and prpperty as well as civil and criminal protection in the courts. But local prejudice among the Cherokee, and the failure of the Choctaw and Chickasaw to adopt their freedpeople as citizens, limited those liberties. With the exception of the Choctaw-Chickasaw vigilante activity of 1865–67, however, freedpeople were not subject to terroristic campaigns, as were former slaves in Texas and the Old South. Even in the Choctaw and Chickasaw nations, where tribal leaders called for their removal, the freedpeople resided without molestation after 1870 in an uneasy accommodation with their former owners.34

The Seminole and Creek Nations allowed their former slaves to participate fully in tribal government. By 1875 the forty-two member National Council, the Seminole legislative body, included six freedmen representing two of the fourteen towns of the Seminole Nation. The House of Warriors, the larger of the two branches of the annually elected Creek legislature, had two or more members (out of eighty-three), representing the three towns populated by freedpeople—North Fork Colored, Arkansas Colored, and Canadian Colored—almost continuously from 1868 until its last session in 1905. Sixteen freedmen served in the 1887 legislature, three in the House of Kings, and thirteen in the House of Warriors. The Creek Nation had the largest and most consistent black political representation anywhere in the West during the last three decades of the nineteenth century. Moreover, in the Arkansas River country, where they were numerically dominant, Creek freedmen were elected judges and district attorneys in tribal courts and district officials for the tribal government. One freedman, Jesse Franklin, was elected justice of the tribal supreme court in 1876. By the mid-1870s “the negroes,” according to Angie Debo, “held the balance of power in Creek politics.”35

Cherokee freedmen voted in their nation’s elections but not without opposition. William P. Boudinot, the influential Cherokee attorney and editor of the Cherokee Advocate, later defended freedpeople in their citizenship claims. In 1878, however, he wrote an editorial attacking black officeholding: “It was not complimentary or just . . . to instill the fatally mischievous idea that [an] element has distinct rights to hold office in proportion to its numbers and irrespective of qualifications.” George W. Johnson, Boudinot’s successor at the Advocate, was more blunt. He wrote in 1879, “We shall at all times object to having our colored citizens sitting in our Council to legislate for us. We know of none that has the capacity to make laws for us.” Nonetheless, beginning with the election of Joseph Brown in 1875, six freedmen served as councillors in the lower house of the Cherokee legislature during the remainder of the century.36

For most Cherokee freedmen, however, citizenship for “intruders,” not electoral office, was the major political question of the day. Many ex-slaves returned in time to become citizens under the provisions of the 1866 treaty. Others, including those carried off by slaveholders to neighboring states, were unaware of the treaty’s provisions or without means to return to the nation. As years passed, these former slaves straggled back into the nation and lived with relatives who were legal citizens. These noncitizens had no rights to the improvements on the lands they made after returning to the nation and could not vote or otherwise participate in Cherokee politics. Further complications arose when blacks from “the State,” believing marriages entitled them to tribal citizenship (as did the marriage of whites to Cherokee), married into the freedpeople families. The extent of the problem became evident after an 1870 census of the Cherokee Nation. Approximately fifteen hundred former slaves had been declared citizens, while seven hundred were intruders. Moreover, the Cherokee National Council in 1869 created special courts to determine individually the cases of intruders and, if necessary, expel them. For many ex-slaves the issue was not simply land or rights as Cherokee citizens but identification with the only home they had known. “I am one of those unfortunates. I came too late,” confessed freedman Joseph Rogers to Cherokee ex-slaves at a Delaware District emancipation celebration on August 24, 1876. Continuing his speech to the freedpeople and addressing, indirectly, the Cherokee political establishment, which determined citizenship, he declared: “Born and raised among these people, I don’t want to know any other. The green hills and blooming prairies of this Nation look like home to me . . . I look around and I see Cherokees who in the early days of my life were my playmates . . . and in early manhood, my companions, and now as the decrepitude of age steals upon me, will you not let me lie down and die your fellow citizen?”37

Cherokee leaders were divided over adopting the intruders. Chief Lewis Downing and his successor, William P. Ross, favored adoption. In his first council address in 1873 Ross asked for the adoption of the freedmen who had returned too late “as a measure humane in its spirit, liberal in its character and expedient in result.” He also requested repeal of all discriminatory statutes. But William P. Boudinot and George W.Johnson, editors of the Cherokee Advocate, and Chief Justice James Vann of the Cherokee supreme court opposed adoption. They argued it would unfairly reduce the land and money remaining in the common heritage of the tribe. “We say to our colored friends that . . . if the treaty of 1866 is . . . not in their favor, there is no hope for them; they cannot live in this nation as citizens. No Cherokee denies them their treaty rights, if the treaty gives them any . . . We admit, their case is a hard one, but it is not our fault.” Vann’s role on the supreme court in determining intruder status was particularly discouraging to freedpeople. In 1871 the court rejected 131 of 136 claims for citizenship.38

The Allen Wilson case reflected the complexities of the citizenship issue for the freedpeople, the Cherokee, and the federal government. Born a slave in the old Cherokee Nation, Allen Wilson came west on the Trail of Tears. During the Civil War he was stranded in the Choctaw Nation after his owner died in 1865. With a large family to support, Wilson farmed to obtain enough money to return to the Cherokee Nation. He returned to the Cherokee Nation in the fall of 1867, seven months after the treaty deadline. Unsure of his status, Wilson went to Cherokee leaders, who told him to begin farming. Wilson’s family built a house on a sixty-acre farm about nine miles east of Fort Gibson. They planted an orchard and nursery and by 1879 had 350 bearing apple trees, 1,000 peach trees, and twelve acres planted in wheat. The family’s industry, however, proved of no avail. When he appeared before a citizenship commission in 1879, Wilson’s claim was rejected and the Cherokee Advocate published a notice of the sale of his farm improvements valued at two thousand dollars.

Wilson was undaunted. When some Cherokee citizens offered to buy his improvements and let him work for them, he declared he would rather sell out and leave the nation. He did neither, and instead hired attorney William P. Boudinot, who argued that his client was a “pattern of industry.” Boudinot appealed to Secretary of the Interior Carl Schurz, who suspended the sale and in turn told U.S. Attorney General Charles Devens to rule on three legal questions: the Cherokee right to determine their citizenship, the right of Cherokee freedpeople to tribal lands under the 1866 treaty, and the responsibility of the federal government to protect Cherokee lands from intruders. The attorney general’s decision declared that the United States was not bound to regard Cherokee law as the final word in intruder cases. The attorney general’s ruling made it virtually impossible for the nation to remove Wilson and other ex-slave intruders. But it also opened the nation and ultimately all Indian Territory to much larger numbers of non-Indian intruders who cared nothing about Indian law, culture, or sovereignty.39

The Chickasaw and Choctaw freedpeople had no rights in their nations, but they were not without influence in Washington, D.C. They sent their political leaders, James Squire Wolf, Squire Butler, Isaac Anderson, and Anderson Brown, to Washington, to represent their interests. They also obtained the removal of the Chickasaw and Choctaw Indian agent George T. Olmstead, whom they held responsible for the attempt to block their tribal rights. They skillfully made their appeals couched in references to their loyalty during the Civil War, reminding their supporters that many of the dispossessed were U.S. Army veterans. Unlike Cherokee freedpeople, they linked their fate to that of blacks from the States. Thus the real thrust of their political incorporation was no longer toward the Indian nations but toward the larger African American community. Some Indian leaders surmised as much. When Chickasaw Governor Benjamin Overton in his annual message of 1876 again urged the legislative council to withhold citizenship from the freedpeople, he declared: “If you [extend citizenship], you sign the death-warrant of your nationality . . . for the negroes will be the wedge with which our country will be rent asunder and opened up to the whites . . .” Overton was partly right. As Chickasaw and Chocktaw freedpeople saw their political and economic interests increasingly diverge from those of their former owners, they campaigned to open the territory to whites and “state negroes.” In the process they weakened Indian control over the nations.40

Outside of Texas and Indian Territory western Reconstruction focused on black male suffrage.* The San Francisco Elevator was speaking as much about California as about South Carolina in 1868 when it called upon the nation to honor its debt not only to black soldiers who fought for the Union during the Civil War but also to “loyal” voters who were necessary to sustain the national Republican administration in Washington. “The Negroes who have rendered . . . signal service in the conflict on the field and at the ballot box,” it declared, “expect the simple recognition of their political rights in every portion of the land.”41

The first indication of congressional concern about black male suffrage occurred when Congress created Montana Territory in 1864. While debating the organic act that authorized the new territory, Minnesota Senator Morton S. Wilkinson introduced an amendment to strike the word white from the section of voter qualifications, prompting a sharp rebuttal from Senator James R. Doolittle of Wisconsin, who erroneously believed no blacks lived in Montana and thus claimed the amendment was meaningless. Senator Charles Sumner conceded the issue was an abstraction, but he nonetheless insisted on the change as a matter of principle. The Senate supported the Wilkinson amendment, but the two houses of Congress compromised by restricting the vote to U.S. citizens, leaving blacks temporarily without suffrage rights on the far western mining frontier. Nonetheless the debate served notice that African American suffrage would no longer be left to the territories.42

Between 1867 and 1869 Congress enacted three measures that enfranchised black males throughout the nation. In January 1867 the vote was granted first to black men in the District of Columbia. Days later Congress passed the Territorial Suffrage Act, which extended the privilege to western territories. Two months later the first Reconstruction Act extended suffrage to freedmen in the former Confederacy. In 1869 Congress passed the Fifteenth Amendment ratified by two-thirds of the states by January 1870, the amendment enabled black men throughout the nation to vote.

If one measures the number of persons affected, the Territorial Suffrage Act had the least impact on black voting. It enfranchised only about eight hundred African Americans, far fewer, for example, than in the District of Columbia. Yet its enactment over Democratic and conservative Republican objections symbolically pointed to the inevitability of national black male suffrage. Speaking before an audience in Virginia City in September 1867 and using the Territorial Suffrage Act as a harbinger of future trends, Nevada Republican Senator William Stewart warned, “It is too late to war against negro suffrage.” Two years later Stewart’s state was the first to ratify the Fifteenth Amendment. Leland Stanford, California’s first Republican governor, writing to U.S. Senator-elect Cornelius Cole, characterized the Civil War as an “incomplete revolution,” which could end only with full suffrage for all citizens—all women as well as black men. Support for black suffrage also came from the far northwest corner of the West. The Olympia Commercial Age in the capital of Washington Territory declared in 1870, soon after the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment, that the measure “does not particularly affect us in this Territory, as the colored folks have been voters among us for sometime already.”43

Despite their small numbers, western African Americans conducted the suffrage campaign with determined energy and courage. In 1865 African Americans from Virginia City, Gold Hill, and Silver City, Nevada, formed the Nevada Executive Committee to “petition the next Legislature for the Right of Suffrage and equal rights before the Law to all the Colored Citizens of the State of Nevada.” Dr. W. H. C. Stephenson chaired the committee and became the principal spokesman in the campaign for civil rights. During the January 1, 1866, anniversary celebration of the Emancipation Proclamation, he told his predominantly white Virginia City audience, “It is for colored men to . . . fearlessly meet the opponents of justice. . . . Let colored men contend for ‘Equality before the Law.’ Nothing short of civil and political rights.”44

Kansas African Americans were equally determined to campaign for their rights. A convention of black men in Lawrence, Kansas, in 1866 challenged the widely held idea that black voting was a privilege the white male electorate could confer or reject at its pleasure. “The right to exercise the elective franchise is an inseparable part of self-government. . . . No man, black or white, can justly be deprived of this right. [It] is not merely a conventional privilege, . . . which may be extended to or withheld from any class of citizen at the will of a majority, but a right as sacred and inviolable as the right of life, liberty or property.” Then the convention issued this warning to Kansas whites: “Since we are going to remain among you, we believe it unwise or inhuman to . . . take from us as a class, many of our dearest natural and justly inalienable rights. Shall our presence conduce to the welfare, peace, and prosperity of the state, or . . . be a cause of dissension, discord, and irritation [?] We must be a constant trouble in the state until it extends to us equal and exact justice.”45

Black westerners resorted to a long-standing protest weapon, the petition. In California, Nevada, Kansas, and Colorado Territory, between 1865 and 1867 they petitioned state and territorial governments for black male suffrage. They also held conventions to urge repeal of other discriminatory laws. Even though their campaigns came in states and territories then dominated by Republicans, all their entreaties were ignored. Daniel Wilder, editor of the Leavenworth Conservative, described popular opinion on equal suffrage in Kansas when he claimed Republicans “talk for it, vote agin it.” His terse comment succinctly summarized the attitudes of many throughout the region.46

Yet blacks could claim one important victory in Colorado Territory. Between 1864 and 1867 Colorado’s 150 African Americans waged a relentless campaign to delay statehood for the territory until their suffrage rights were guaranteed. Colorado’s black males began campaigning in 1864, when the territorial legislature limited voting to white males. African American men angrily denounced the measure, claiming it denied them a right they had exercised since 1861. In July 1864 they sent a delegation to the state constitutional convention, where it lobbied unsuccessfully for equal male suffrage. When the entire constitution was rejected by the voters in 1865, a second convention again proposed the amendment and submitted the suffrage question to the voters. They narrowly approved the revised constitution by 155 votes but rejected black male suffrage by 4,192 to 476.47

African-American Coloradans refused to accept the decision. Three Denver barbers, Edward Sanderlin, Henry O. Wagoner, and William Jefferson Hardin, urged the U.S. Congress to delay Colorado’s statehood until black male suffrage rights were assured. Kentucky-born Hardin, who had arrived in Denver in 1863, quickly assumed the leadership of this effort, writing Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner, Ohio Representative James Ashley, and Horace Greeley, editor of the New York Tribune, to outline the grievances of the territory’s African Americans. Hardin issued an ominous warning in his February 1866 missive to Senator Sumner: “Slavery went down in a great deluge of blood, and I greatly fear, unless the american [sic] people learn from the past to do justice now & in the future, that their cruel & unjust prejudices will, some day, go down in the same crimson blood.” Greeley responded to Hardin’s request by insisting that black suffrage, while desirable, should never be a condition of statehood. Senator Summer, however, declared his opposition to statehood . because of the suffrage restriction after reading aloud the black Coloradan’s telegram before the U.S. Senate.48

Hardin also targeted territorial political leaders. In December 1865 he presented to Territorial Governor Alexander Cummings a petition signed by 137 Colorado African Americans, 91 percent of the territory’s black population, calling for repeal of the suffrage restriction. To deny equal suffrage, the petition asserted, was to disregard “the bloody lessons of the last four years.” Governor Cummings forwarded the petition to Secretary of State William Seward for presentation to Congress. In January, Hardin, Henry O. Wagoner, and four other African Americans presented a second petition to Cummings, who forwarded it to the territorial legislature with his own appeal for equal suffrage. The legislature ignored both the petition and the governor’s message.49

Black Coloradans’ efforts seemed a failure. The territorial legislature felt no compulsion to respond to their demands, and the U.S. Congress actually voted in April 1866 to admit Colorado only to see the admission blocked by a veto by President Andrew Johnson. The president, who was certainly no advocate of black suffrage, gave as his reason for the veto the small population of the territory. But the debate over black suffrage restrictions in Colorado generated an unanticipated development. On the day that President Johnson issued his veto, Representative Ashley, chair of the Committee on Territories, introduced a bill regulating territorial government.Included in its provisions was a measure to give all male residents (Indians excepted) the right to vote. The bill passed the House of Representatives but died when the Senate failed to act on the measure.50

In January 1867, while the Senate debated black voting in Colorado, Ohio Senator Benjamin Wade resurrected Ashley’s bill, arguing that it would solve the problem of equal suffrage in all the territories. He successfully maneuvered the bill through the Senate on January 10 and that afternoon rushed it to the House, where it was approved within two hours. The Territorial Suffrage Act became law without President Johnson’s signature on January 31, 1867. Consequently black males in Colorado and other territories achieved voting rights at least three years before ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment ensured similar rights in northern and western states.51

Black males in western territories quickly exercised their newly won suffrage rights. Two hundred black men cast ballots in the Montana territorial election of 1867, although not without challenge. Pro-Democratic gangs circulated throughout Helena on election day in 1867 to intimidate black voters; Sammy Hays was killed by a gang of Irish toughs. However, most blacks recorded their votes and left the polling places without incident. Six black voters, men and women, who intended to cast ballots in South Pass City, Wyoming Territory, in 1869, faced an angry mob of mostly Democratic gold miners who blocked their route to the town’s polling place. Only the timely intervention of the territory’s Republican-appointed U.S. marshal, Church Howe, saved the day. Howe marched to the polls beside the voters, gun in hand, threatening to shoot anyone who got in the way.52

Despite rumors of possible mob action against Colorado blacks during 1867 municipal elections in Denver and Central City, no violence occurred. Instead Colorado Republicans courted the newly enfranchised voters. Republican newspaper editor D. C. Collier flattered black voters by claiming that though he believed most southern freedmen were incapable of voting wisely, “in Colorado, negro suffrage is intelligent suffrage. . . . We believe the negro in this Territory is fully capable of exercising the franchise.” Such flattery soon proved crucial. In the 1868 election of the territory’s congressional delegate, Denver’s 120 black votes secured the victory for Republican candidate Allen Bradford in his 17-vote margin over his Democratic opponent, David Belden. Republicans publicly acknowledged their debt. When one maverick Republican proposed the temporary disfranchisement of blacks, party leaders immediately dismissed the idea. “We would lose our Republican majority,” said one, while another wrote, “[W]ithout the colored vote Bradford would never have been elected. Now it is proposed to take the right of voting away from the men who saved the Republican Party.”53

Suffrage for African American males in western states other than Texas (which was covered under the Congressional Reconstruction Act of 1867) came with the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment. In those states black efforts focused on securing ratification of the amendment. Of the five western states that considered ratification, three, Kansas, Nebraska, and Nevada, endorsed the measure. Nebraska, as a condition of its admission in 1867, already allowed black suffrage, while Nevada held the distinction of being the first state in the Union to ratify the Fifteenth Amendment because its senator, William Stewart, was a principal congressional sponsor. Democratic-controlled legislatures in California and Oregon, however, adamantly opposed black voting. Oregon’s legislature called it an unconstitutional “change forced upon the states by the power of the bayonet.”54

The Kansas ratification was the most surprising since it occurred three years after a bitter campaign that pitted supporters of black male suffrage against woman suffrage advocates. The white male electorate overwhelmingly rejected both black and female suffrage, undermining Kansas’s claim to be the “the most radicalized state in the Union.” The campaign began in 1862, when African American political leaders petitioned the state legislature for the right to vote. Although the campaign was supported by sympathetic white men, including Daniel Wilder, the editor of the Leavenworth Conservative, Charles H. Langston, an African American farmer and grocer from Lawrence, emerged as its leader. Born a slave on a Virginia plantation in 1817, Charles and his younger brother, John Mercer Langston, another antebellum abolitionist who became a U.S. representative from Virginia in 1889, were freed and educated at Oberlin College in Ohio. In 1848, already an experienced political activist, Charles Langston as an Ohio delegate attended the National Negro Convention (where he joined Frederick Douglass in enrolling other delegates). In 1859 Langston was arrested for violating the terms of the Fugitive Slave Act when he helped John Price escape to Canada. Although his brother returned to Virginia after the Civil War, Charles Langston emigrated west to Kansas in 1862 to teach and work among the freedpeople.55

The Kansas legislature at first refused to take action on the black male suffrage petition, claiming that such a weighty measure could not be decided while the state’s soldiers were fighting the Civil War. When petitions were again presented in 1866, the legislature delayed until Governor Samuel Crawford recommended a statewide referendum on the issue. The legislature subsequently drafted the measure, scheduled for the November 1867 election, which removed the word white from the state suffrage law. However, Republican legislator Samuel N. Wood added a second provision calling for removal of the word male. Wood had opposed all previous measures broadening suffrage to include anyone other than white males. Thus many black suffrage supporters concluded that his real intent was to defeat both reforms.

The coupling of voting rights for black males and all women revealed the complexities of race and gender and the difficulty of maintaining coalitions in the face of varied opposition. The white male electorate divided into four camps. Some supported equal suffrage for all men and women, while advocates of gender or racial equality selfishly promoted their own reform at the expense of the other. Opponents of both reforms concluded that neither women nor black men were worthy of suffrage and urged defeat of both proposals. At the height of the Kansas campaign Thomas Hartley, a conservative Republican, published a pamphlet, Universal Suffrage—Female Suffrage, which argued that giving votes to women and to black men would invite demagogues into office by placing political power in the hands of “children” who would be swayed by emotion rather than serious intellectual reflection.56

Undaunted by such arguments, and refusing to accept the “black vote first” approach of most reformers of the era, national and state woman suffrage advocates seized the opportunity provided by the Kansas referendum to gain their first statewide victory. National suffrage leaders, such as Lucy Stone, Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and the Reverend Olympia Brown, campaigned throughout Kansas, accompanied by state leaders, such as Clarina Nichols and Sallie Brown.57

African American men in Kansas marshaled no comparably known national leaders to campaign for their suffrage. It fell to Charles H. Langston, Daniel Wilder, and other supporters to carry the campaign. Despite creation of the Impartial Suffrage Association to support both reforms (with Governor Crawford as honorary president), woman suffrage and black suffrage advocates were soon hurling charges against each other. “Negroes of Kansas and their friends are claiming rights which they are not willing to give to mothers, wives, sisters and daughters of the state,” declared Samuel Wood. Speaking before an audience in Fort Scott, Kansas, the Reverend Olympia Brown “disclaimed against placing the dirty, immoral, degraded negro before a white woman,” while Sallie Brown warned that “if the negroes get the ballot [before women] there will be no chance for us . . .”58

African American leaders were more circumspect in their public comments on women’s suffrage. “I have no dispute with you . . .” Langston wrote to Samuel Wood, “there shall be no antagonism between me and the friends of woman suffrage.” However in private correspondence with Wood two months earlier, a clearly furious Langston wrote: “I feel that you are responsible . . . for all the . . . unnecessary and embarrassing notions . . . in connection with the question of negro suffrage. I am not alone in this feeling. . . . If the measure is defeated, by these frivolous, extraneous, and distinctive motions, we the negroes shall hold you responsible.” Indeed Langston was not alone in his feelings. One month before the election he persuaded a reluctant black convention meeting in Doniphan County to pass a resolution denying any rivalry between advocates of black and woman suffrage. White Republican leaders such as state Attorney General G. W. Hoyt and future Senator Preston B. Plumb exercised no similar restraint: They openly opposed woman suffrage while supporting black male suffrage. When the votes were counted, both measures went down to defeat. Black suffrage failed by 19,421 to 10,438, and woman suffrage collapsed under a slightly wider margin, 19,857 to 10,070. Three years later Kansas Republicans, concluding that the Fifteenth Amendment was the only means of gaining black suffrage, urged rapid ratification before legislative opposition could mount. That opposition did appear, but the national momentum toward ratification swept the amendment through the Kansas legislature in January 1870.59

Western African Americans celebrated the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment with “unrestrained elation” unmatched since the Emancipation Proclamation. Philip Bell proclaimed: GLORIA TRIUMPHE! WE ARE FREE! from the pages of the Elevator as his newspaper reported celebrations in California, Oregon, and Nevada. Black citizens of Helena, Montana Territory, assembled on the south hill overlooking the city to announce “to the wide world that we are free men and citizens of the United States—shorn of all those stigmatizing qualifications which have made us beasts.” They then thanked God and the Congress of the United States and fired a thirty-two-gun salute. Nevada blacks at opposite ends of the state, in Virginia City and Elko, celebrated. The Elko residents had proposed to fire a cannon salute. Upon discovering there were no cannon in the town, they settled instead on hammering “two large anvils for that purpose.” A procession of 150 black Nevadans paraded from Virginia City to neighboring Gold Hill, “playing popular patriotic airs” and flying a “fine silk flag” made by the black women of Virginia City for the occasion and inscribed with the words Justice is slow, but sure. Portland African Americans staged a “Ratification Jubilee.” The celebrants, marching to the music of the Twenty-third U.S. Infantry Band, staged a torchlight procession to the courthouse, where they were addressed by seven orators, including local African American businessman George P. Riley and prominent Republicans Elisha Applegate, a founder of the party in Oregon, and ex-Governor Addison C. Gibbs. Black Portlanders solemnly declared their loyalty to the nation, “should our country need us.”60

One consequence of black voting was officeholding. By the end of the nineteenth century African Americans held office in Texas, Kansas, Colorado, Washington, and Wyoming. African Americans such as Edwin McCabe, the Kansas auditor in 1881, and “Colonel” John Brown, the Shawnee County, Kansas, clerk in 1889, successfully competed against whites for local office. Some African American politicians achieved national prominence. John Lewis Waller served as ambassador to Madagascar in the 1890s. However, few were as interesting as William Jefferson Hardin. By 1873 Hardin had moved to Cheyenne, Wyoming Territory, after a personal scandal cost him his position at the Denver Mint. He resumed his trade as a barber and in 1879 entered state politics and was elected to two terms in the territorial legislature.61

Politics of course would not resolve all the issues facing black communities in the West any more than elsewhere in the nation. Some late-nineteenth-century leaders, such as Booker T. Washington, criticized the inordinate energy and resources devoted to obtaining elective and appointive office particularly in the face of the poverty and marginalization of African American communities. Yet with voting rights permanently assured for black men throughout the region except in Texas and the Chickasaw and Choctaw Indian Nations and for black women in Wyoming by 1869 and other western states by the 1890s, western African Americans could proudly echo Peter Anderson’s call for blacks to see their economic destiny in the “Great West.”62

Nineteenth-Century Black Western Legislators, 1868–1900

|

|

Colorado |

|

John T. Gunnell |

1881–83 |

Joseph H. Stuart |

1895–97 |

|

|

Indian Territory |

|

Creek Nation |

|

Sugar George |

1868–74, 1882–85, 1887–89, 1892, 1894–95 |

Simon Brown |

1868 |

Charles Foster |

1869, 1873 |

Isom Marshall |

1871 |

Harry Island |

1872 |

Ned Robbins |

1872, 1875, 1887, 1890 |

Robert Grayson |

1872, 1875, 1883, 1885, 1887, 1893, 1900 |

Jesse Franklin |

1872, 1873, 1881 |

Benjamin McQueen |

1872, 1873 |

Scipio Sancho |

1872–73, 1882 |

Thomas Bruner |

1872, 1875, 1886 |

Toby McIntosh |

1872–73 |

William McIntosh |

1872 |

Samson Hawkins |

1875 |

Monday Durant |

1875 |

Simon Brown |

1875 |

Jeffrey Smith |

1875 |

Daniel Miller |

1875 |

Pardo Bruner |

1875, 1887, 1889–90, 1895 |

Ben Barnett |

1875 |

Jack McGilbra |

1875 |

Sandy Perryman |

1875 |

Tom Richards |

1875 |

Snow Sells |

1882–83, 1895 |

William Peter |

1882, 1889 |

Gabriel Jameson |

1883–85, 1887–89, 1894 |

J. P. Davison |

1883, 1885, 1887, 1890, 1899 |

H. C. Reed |

1884, 1887–88, 1894–95 |

Joshua Tucker |

1884 |

Manuel Warrior |

1885 |

Manuel Jefferson |

1885 |

Abraham Prince |

1885 |

Simon Rentie |

1885, 1890–91 |

Isom Jameson |

1885 |

Stepney Colbert |

1885 |

Dan Miller |

1887 |

Moses Jameson |

1887, 1894 |

Eli Jacobs |

1887 |

Solomon Franklin |

1887, 1890 |

Robert Walker |

1887 |

Green Jackson |

1887 |

Morris Sango |

1887 |

Tony Sandy |

1887 |

John Meyers |

1887 |

Isaac Manual |

1888 |

Warrior A. Rentie |

1893, 1895, 1899 |

Alec Davis |

1893 |

Stepney Durant |

1893 |

Kellop Murrell |

1895 |

Dan Tucker |

1895 |

Joe Primus |

1895 |

P. A. Lewis |

1899 |

Alec H. Mike |

1899 |

A. G. W. Sango |

1899–1900 |

Lewis B. Bruner |

1900 |

Wiley McIntosh |

1900 |

Cherokee Nation |

|

Joseph Brown |

1875–77 |

Frank Vann |

1887–89 |

Jerry Alberty |

1889–91 |

Stick Ross |

1893–95 |

Ned Irons |

1895–97 |

Samuel Stidham |

1895–97 |

Seminole Nation |

|

Ben Bruner |

1868–79 |

William Noble |

1868–89 |

Caesar Bruner |

1880–1900 |

Joe Scipio |

1890 |

Joe Davis |

1891 |

Dosar Barkus |

1892–1900 |

|

|

Kansas |

|

L. W. Winn (Senate)* |

1879 |

Alfred Fairfax |

1889–91 |

|

|

Nebraska |

|

Dr. Moses O. Ricketts |

1892–96 |

|

|

Oklahoma Territory |

|

Green Jacob Currin |

1890–92 |

D. J. Wallace |

1892–94 |

|

|

Texas |

|

George T. Ruby (Senate) |

1870–71, 1873 |

Matthew Gaines (Senate) |

1870–71, 1873 |

Walter M. Burton (Senate) |

1874, 1876, 1879, 1881 |

Walter Riptoe (Senate) |

1876, 1879 |

Mitchell M. Kendall |

1870–71 |

D. W. Burley |

1870–71 |

Richard Williams |

1870–71, 1873 |

Henry Moore |

1870–71, 1873 |

Richard Allen |

1870–71, 1873 |

R. Goldstein Dupree |

1870–71 |

John Mitchell |

1870–71 |

Silas Cotton |

1870–71 |

Sheppard Mullins |

1870–71 |

Benjamin Franklin Williams |

1870–71, 1879, 1885 |

Jermiah J. Hamilton |

1870–71 |

David Medlock |

1870–71 |

Shack R. Roberts |

1873, 1874, 1876 |

Henry Phelps |

1873 |

James H. Washington |

1873 |

Allen Wilder |

1873, 1876 |

Edward Anderson |

1873 |

David Abner, Sr. |

1874 |

Edward J. Brown |

1874 |

Thomas Beck |

1874, 1879, 1881 |

Jacob E. Freeman |

1874, 1879 |

John Mitchell |

1874 |

Henry Sneed |

1876 |

William H. Holland |

1876 |

R. J. Evans |

1879, 1881 |

B. A. Guy |

1879 |

Harriel G. Geiger |

1879, 1881 |

Elias Mayes |

1879, 1889 |

Andrew L. Sledge |

1879 |

Robert A. Kerr |

1881 |

D. C. Lewis |

1881 |

R. J. Moore |

1883, 1885, 1887 |

George W. Wyatt |

1883 |

James H. Stewart |

1885 |

H. A. P. Bassett |

1887 |

Alexander Ashberry |

1889 |

Edward A. Patton |

1891 |

Nathan H. Haller |

1893, 1895 |

Robert L. Smith |

1895, 1897 |

|

|

Washington |

|

William Owen Bush |

1889–91 |

|

|

Wyoming |

|

William Jefferson Hardin |

1879–84 |

|

|

* Appointed to fill unexpired term.

Sources: Rebecca Lintz, reference librarian, Colorado Historical Society, to author, April 28, 1994; Daniel Littlefield to author, February 1, 1996; Kevin Mulroy to author, August 9, 1996; Thomas C. Cox, Blacks in Topeka, Kansas, 1865–1915: A Social History (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1982), 122–23; Works Projects Administration, The Negroes of Nebraska (Lincoln: Woodruff Printing Company, 1940), 28; Oklahoma Historical Society to author, October 27, 1995; Emmet Starr, History of the Cherokee Indians (Millwood, N. Y.: Kraus Reprint Company, 1977), 277–83; Barry A. Crouch, “Hesitant Recognition: Texas Black Politicians, 1865–1900,” East Texas Historical Journal 31:1 (Spring 1993), 53–56; Barton’s Legislative Hand-Book and Manual of the State of Washington, 1889 (Tacoma: Thomas Henderson Boyd, 1889), 224; and Eugene Berwanger, The West and Reconstruction (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1981), 183–84.

* Much like African American political leaders in the rest of the nation, black westerners sought the right to vote for black men. Apparently few black western women called for suffrage to be extended to them, and there is little evidence they were active in either black male campaigns or in woman suffrage efforts led by white women. African American women, however, did gain suffrage rights in western states and territories, beginning with Wyoming in 1869, and thus voted years before most of their southern or eastern counterparts.