In his speech at the First State Convention of the Colored Citizens of the State of California in 1855, the San Francisco minister Darius Stokes proclaimed to the world that African Americans, were destined to stay in California and the West. “The white man came, and we came with him; and by the blessing of God, we shall stay with him, side by side. . . . Should another Sutter discover another El Dorado . . . no sooner shall the white man’s foot be firmly planted there, than looking over his shoulder he will see the black man, like his shadow, by his side.” Stokes spoke of the gold rush era, but his words applied equally to the post–Civil War West. African Americans by 1870 inhabited every state and territory of the region. From Fort Benton, Montana Territory, where roustabouts unloaded the river-boats along the headwaters of the Missouri River, to soldiers stationed at Fort Huachuca, Arizona, or Fort Davis, Texas, blacks were no mere proverbial “shadow.” Often they led the way for subsequent settlers. None of this is surprising. Since the eighteenth century, when blacks ventured north from central Mexico to California, New Mexico, Texas, and other remote outposts of New Spain, African Americans have sought out the region.1

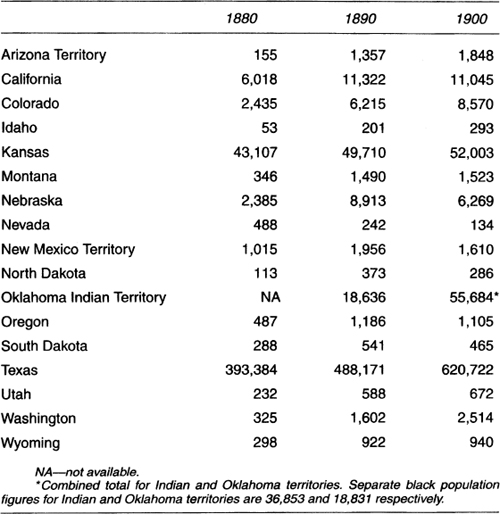

The African American Population in Western States and Territories, 1880–1900

Source: U.S. Bureau of the Census, Negro Population in the United States, 1790–1915 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1918), 43, 44; Michael D. Doran, “Population Statistics of Nineteenth Century Indian Territory,” Chronicles of Oklahoma 53:4 (Winter 1975), 501; and U.S. Bureau of the Census, Twelfth Census of the United States, 1900, vol. 1, Population, part 1 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Census Office, 1901), 537, 553.

African American entry into the region differed from the image of westward migration. Few blacks crossed the plains and mountains in wagon trains. Instead those traveling from the South were likely to come by railroad or steamboat. Many more took the transportation naturally available to a newly freed people: They walked. Most settlers came westward into Texas, Indian Territory, and Kansas from the Old South. Texas wages of twenty dollars per month, double those of Virginia, North Carolina, and Tennessee, encouraged a steady stream of freedpeople westward. The hundreds of North Carolina freedpeople who migrated to Texas in 1879 pursued goals similar to those of the much larger Exoduster movement to Kansas. Prevented from claiming public lands by the provisions of the Texas Homestead Act and discouraged from owning farms elsewhere in the state, these former North Carolinians settled in cotton-growing areas, becoming agricultural workers or sharecroppers much like their counterparts in the states east of the Sabine. By the 1890s many of them had joined John B. Rayner, Melvin Wade, and other ex-Republicans in the state’s major nineteenth-century political insurgency, the Populist party.2

African Americans also moved to Indian Territory mainly from Arkansas and Tennessee. They became farmers, but on lands they could not possess until 1889 and in areas where their status as intruders subjected them to removal. Kansas absorbed twenty-five thousand black emigrants during the 1870s and early 1880s. As the closest western state to the Old South in the 1870s that allowed black home-steading, it became the destination for a particularly intrepid group of migrants. Most of these newcomers were from neighboring Missouri, but other border states, such Kentucky, Tennessee, and Virginia, and Deep South states, such as Mississippi and Louisiana, were also increasingly represented.

Kansas loomed large in the minds of many African American southerners. The state offered potential homesteaders access to vast tracts of undeveloped farmland. The 1862 Homestead Law, which applied to Kansas and other western states and territories, was uncomplicated and unambiguous. The federal government provided 160 acres of free land to any settler, regardless of race or sex, who paid a small filing fee and resided on and improved the land for five years. However, the settler could choose to purchase the land for $1.25 per acre after living on it for six months.3

The Republican party dominated Kansas politics, no small consideration for those who saw their rights quickly erode after Democrats returned to power in the former Confederacy by 1877. Moreover, Kansas carried a powerful abolitionist tradition. Here John Brown had first struck to free slaves, and here the first black soldiers had joined the Union army. Kansas had applauded the Emancipation Proclamation and been among the first states to ratify the Thirteenth Amendment. “I am anxious to reach your state,” wrote a black Louisianian to the governor of Kansas in 1879, “not because of the great race now made for it but because of the sacredness of her soil washed by the blood of humanitarians for the cause of black freedom.” Numerous Quakers, Presbyterians, and Congregationalists moved to the state after the Civil War, proudly embracing their “sense of mission toward the Negro.” With their help Kansas became to the freedperson what the United States was to the European immigrant: a refuge from tyranny and oppression.4

African American migrants also anticipated fertile farmlands. George Marlowe, who represented a black emigration agency in Louisiana, wrote a glowing report after an eight-day visit in 1871: “What is raised yields more profit than elsewhere, and it is raised at less expense. The weather and roads enable you to do more work than elsewhere. . . . The country is well watered . . . [and] produces 40–100 bushels of corn and wheat to the acre and the corn grows 8 to 9 5-feet high.” Such enticements drew thousands of black settlers, including young George Washington Carver, to west Kansas. In 1886 Carver claimed 160 acres of land in Ness County, built a modest sod house, and raised corn and vegetables for two years before leaving the area to continue his education in Iowa.5

Most African Americans who moved to Kansas came, like Carver, as individuals or in families, but some arrived through various emigration agencies. Of the groups, the Tennessee Real Estate and Homestead Association, founded by Benjamin (“Pap”) Singleton, was the most successful. Born a slave near Nashville, Tennessee, in 1809, Singleton spent much of his life as a cabinetmaker. Sold off to the Deep South, he escaped to Detroit, where he operated a boardinghouse that often harbored fugitive slaves. After the war he returned to Nashville and became a carpenter. Convinced that the salvation of southern blacks lay in farm ownership rather than in sharecropping or wage labor, Singleton by 1871 had turned to Kansas, where homesteaded land could be acquired for $1.25 per acre.

In 1878 Singleton led his first emigrants, a party of two hundred settlers to the east bank of the Neosho River in Morris County, where he established the Dunlop colony, taking up residence there himself in 1879 and 1880. The colony illustrated both the prospects and the problems of Kansas colonization by the freedpeople. From 1846 to 1872 the colony’s land was part of the Kansa Indian Reservation, which originally covered 256,000 acres. Under pressure from settlers, the federal government in 1859 reduced the reservation to 80,000 acres and in 1872 removed the last of the Kansa Indians to Indian Territory. Two years later Joseph Dunlop, a former trader with the Kansa, laid out the town and built the colony’s first store near the Missouri, Kansas, and Texas Railroad. By 1878, when Singleton and his followers arrived, most of the best river and creek bottom farmland belonged to speculators and the railroad. The remainder, priced at $7 per acre, was still considered too expensive for the emigrants. Nonetheless, persuaded by exaggerated claims of the local boosters that the Neosho River valley was an idyllic agrarian environment, Singleton settled for the less fertile uplands, where colonists could purchase 80-acre homesteads for $1.25 to $2 per acre. In all, the colonists bought 7,500 acres of land to grow wheat, corn, vegetables, and other cash crops on land used today for cattle grazing.6

Had the colony remained agricultural, those who first arrived might have prospered. Events in Topeka, however, soon overtook the colony. The 1879 Exodus brought thousands of blacks to Kansas in a matter of months and prompted Governor John St. John to establish the Kansas Freedmen’s Relief Association (KFRA) to “aid destitute freedmen, refugees, and emigrants.” Encouraged by what they interpreted as sympathy and support, additional exodusters concentrated in the Kansas capital. Facing the prospect of clothing, housing, and feeding these thousands of exodusters, the KFRA chose to resettle them in rural Kansas, on the already established Dunlop colony. Four hundred new settlers arrived in the colony, built makeshift homes, and worked, when possible, for local ranchers.7

The relocation effort soon became an example of good intentions gone awry. KFRA moved the refugees onto impractically small homesteads. The association subdivided the 240 acres into twenty-eight lots with either 5 or 10 acres of land. The average white farmer in the area had 160 acres, most of the original colonists still had 80-acre homesteads, but the Exodusters often cultivated about 2 acres of their 5- to 10-acre “farms” and owned little livestock. None of the farms were self-sufficient; exodusters survived mainly by work on ranches, on larger farms, and in neighboring towns through or subsidies from local charities. The Dunlop colony population peaked at one thousand in the early 1880s and declined to less than five hundred by the end of the century as many colonists or their children moved to the cities.8

Benjamin Singleton was the most famous Kansas emigration leader. Yet he played no role in founding Nicodemus, Kansas’s best-known black community. That distinction goes to six men—W. H. Smith, Benjamin Carr, president and vice-president respectively of the Nicodemus Town Company, Jerry Allsap, the Reverend Simon Roundtree, Jeff Lenze, and William Edmonds—who envisioned a black agricultural community west of the hundredth meridian near what was in 1877 the west Kansas frontier. They named their community Nicodemus after a legendary African slave prince who purchased his freedom. They chose to locate Nicodemus on the Solomon River. They also decided to recruit settlers from among their former friends and neighbors in central Kentucky.9

In July 1877, 30 colonists arrived at Nicodemus from Topeka, followed by 150 in March 1878. Additional settlers arrived later that year from Kentucky, Tennessee, Missouri, and Mississippi. Nothing in their experience prepared them for life in western Kansas. Graham County had 75 residents, primarily cattlemen, when the first colonists arrived. The flat, barren, windswept high plains, known for blazing summer heat and bitter winter cold, were better suited to growing cactus and soapweed than corn and wheat. Willianna Hickman, a settler in the 1878 migration to Nicodemus, wrote excitedly of navigating across the plains by compass. Finally she heard fellow travelers exclaim: “There is Nicodemus!” Expecting to find buildings on the horizon, she said, “I looked with all the eyes I had. ‘Where is Nicodemus? I don’t see it.’ ” Her husband responded to her query by pointing to the columns of smoke coming out of the ground. “The families lived in dugouts,” she dejectedly recalled. “We landed and struck tents. The scenery was not at all inviting and I began to cry.”10

By 1880, 484 African Americans, 11 per cent of the total population, lived in Graham County, while 258 blacks and 58 whites resided in Nicodemus and the surrounding township. The separation between town dweller and farmer was inexact because many townspeople were waiting for their opportunity to homestead land. Even Nicodemus boardinghouse owner Anderson Boles by 1881 had 75 acres of wheat under cultivation. The Graham County migrants were better prepared for homesteading than the Dunlop colonists. After initially difficult years most settlers by 1881 had planted 10 to 15 acres to wheat and corn and began to acquire some livestock. The first settlers had little farm equipment and faced drought, prairie fires, crop failures, and grasshopper swarms. Nonetheless many of them succeeded. R. B. Scruggs, a self-described “ole green boy, never ’way from home,” before settling in Nicodemus in 1878, supplemented his meager farm income by driving a freight wagon and working as a railroad section hand during his first years in the West. His perseverance paid off; his original 120-acre homestead grew to a 720-acre farm.11

Nicodemus Township emerged as a briefly thriving community that served a surrounding countryside once described by a local newspaper as so flat “that you can see what your neighbors are doing in the next township.” The Boles House, operated by Anderson Boles, and the Myers House, owned by J. M. Myers, and Eliza Smith’s Gibson House all provided food and accommodations to visitors. Smith, a former Denverite, was unusual in the community not for her gender but because she emigrated to Nicodemus from farther west. John W. Niles opened the first livery stable in 1880 near John Lee’s blacksmith shop. Z. T. Fletcher, the town postmaster, also operated a succession of businesses, the most prominent of which was the St. Francis Hotel, established in 1885. Two white residents were responsible for the town’s only newspapers. Arthur G. Tallman established in 1886 the Nicodemus Western Cyclone, which had a brief newspaper monopoly until Hugh K. Lightfoot founded the Nicodemus Enterprise one year later. Two other prominent white businessmen integrated themselves into the economic and political life of Nicodemus. A former New Yorker, S. G. Wilson, erected the first two-story stone building in 1879, when he established the general store. C. H. Newth, a European-born physician, operated the drugstore for Nicodemus. “Nicodemus,” wrote Cyclone editor Lightfoot, “is the most harmonious place on earth. . . . Everybody works for the interest of the town and all pull together. . . .” By 1886 Nicodemus had Baptist, Free Methodist, and African Methodist Episcopal churches and a new schoolhouse, considered one of the finest buildings in the town. Nicodemus’s residents celebrated the Fourth of July, September 17 (the town founding day), and West Indian Emancipation Day, August 1, all of which included a community celebration of “speeches, dancing, a carnival, and . . . a great variety of food served under the trees of R. B. Scruggs’ grove.”12

Nicodemus’s success attracted other African Americans, including Edwin P. McCabe. A Troy, New York, native born in 1850, McCabe worked on Wall Street before moving to Chicago in 1872, where he was appointed a clerk in the Cook County office of the federal Treasury. He arrived in the Nicodemus settlement in 1878 and, after advertising himself as an attorney and land agent, began surveying land and locating settlers on their claims. When Governor John P. St. John established Graham County in April 1880, McCabe was appointed temporary county clerk, beginning a long career of officeholding. In November 1881 McCabe was elected to a full-term as clerk, and the following year, at the age of thirty-two, he became the highest-ranking African American elected official outside the South when Kansas voters chose him as state auditor. Nicodemus had other black elected officials, including John DePrad, who succeeded McCabe as county clerk; Daniel Hickman, who chaired the Graham County Board of Commissioners; and W. L. Sayers, a prominent Hill City lawyer who was county attorney.13

As the first predominantly black western town to receive national attention, Nicodemus became an important symbol of the African American capacity for self-governance and economic enterprise. Yet the town’s prospects, always precarious, had gone into steady decline by the end of its first decade. First the weather struck. The winter blizzards of 1885 destroyed 40 percent of the township’s wheat crop, prompting an exodus. Two years later town leaders placed their hopes and sixteen thousand dollars in railroad bonds, in unsuccessful efforts to attract the Missouri Pacific, the Santa Fe, and the Union Pacific railroads to their town. When all three railroads bypassed Nicodemus, its fate was sealed. After 1888 local boosters ceased trying to lure additional settlers, and prominent citizens, including most notably Edwin McCabe, left the area.14

The settlement of a few hundred blacks in Morris and Graham counties presaged a much larger influx of southern African Americans into Kansas in the spring and summer of 1879. Named the Exodus, this movement swept some six thousand blacks from Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas into Kansas. As earlier in the decade, southern hardships pushed the migration as much as Kansas opportunity pulled it. Although the “Kansas fever” generated images of a leaderless millenarian movement of impoverished freedpeople, driven by blind faith toward a better place, it was, as Nell Painter has shown, a rational response to a hopeless condition in the South. When Kansas critics called for barring impoverished Exodusters, one emigrant had this rejoinder: “That’s what white men go to new countries for, isn’t it? You do not tell them to stay back because they are poor. Who was the Homestead Act made for if it was not for poor men?” An unidentified black woman’s response was more succinct. When a St. Louis Globe reporter asked the woman with a child at her breast if she would return to the South, she replied, “What, go back! . . . I’d sooner starve here.”15

John Solomon Lewis’s family saga embodied the movement. The Lewis family lived in heavily black Tensas Parish, Louisiana, on the west bank of the Mississippi River. There they and other African Americans suffered grinding poverty. Lewis, however, challenged the local landowner: “It’s no use, I works hard and raises big crops and you sells it and keeps the money . . . so I will go somewhere else and try to make headway like white workingmen.” When Lewis’s angry landlord threatened to have him shot for his defiance, he and his wife and their four children fled to the woods for three weeks, waiting for a riverboat to take them away. The Lewis family reached Kansas a few weeks later with other black Exodusters who solemnized their entry into the state with a meeting to offer prayers of thanksgiving. “It was raining but the drops fell from heaven on a free family, and the meeting was just as good as sunshine. . . . I asked my wife did she know the ground she stands on. She said, ‘No.’ I said ‘it is free ground’ and she cried like a child for joy.”16

Reactions to the influx of southern blacks was predictably varied. The New West, a journal that promoted settlement in Kansas, suggested that the freedpeople would have a chance for advancement denied them in the South. “Whatever befalls them in Kansas they at least have a chance to rise and fall on their own merits.” The Topeka Colored Citizen celebrated the exodus and added: “Our advice . . . to the people of the South, Come West, Come to Kansas . . . in order that you may be free from the persecution, and cruelty, and the deviltry of the rebel wretches. . . . If they come here and starve, all well. It is better to starve to death in Kansas than be shot and killed in the South.” But the newspaper also cautioned the Exoduster: “Remember that in Kansas everybody must work or starve. This is a great state for the energetic and industrious, but a fearful poor one for the idle or lazy man.” However, Republican Mayor Michael C. Case spoke for many Topekans when he refused to spend municipal funds to aid the Exodusters. Moreover, the money spent by the KFRA to house and feed the Exodusters, he suggested, would be better used for returning them to the South. The oppression by the southern Democrats was, according to the mayor, a just reward for blacks “who were always talking politics.”17

Without assistance from the city, state, or federal government (where Kansas Senator John Ingalls and Ohio Representative James A. Garfield both introduced unsuccessful relief bills), the burden fell to the Kansas Freedman’s Relief Association. It hired two people to direct the relief efforts. John M. Brown, an African American schoolteacher from Mississippi, was made general superintendent of KFRA properties, primarily the Barracks, a shelter erected along the Kansas River as the temporary home of most Exodusters. Brown also headed the resettlement efforts. Laura Haviland, a white Quaker philanthropist from Michigan, became the organization’s secretary and solicited relief supplies and donations. In response to a national appeal, black and white religious and civic organizations sent assistance. Edwin McCabe, then residing in Chicago, brought a boxcar of food and clothing and a check for $2,000, which he presented to Governor St. John. John Hall, a Philadelphia Quaker, donated $1,000, and Chicago meat-packer Philip D. Armour collected $1,200 from local businessmen. Laura Haviland reported in 1881 that the KFRA had received more than $70,000 in supplies and cash, $13,000 from England. Even William Lloyd Garrison, who publicly questioned the Exodus, directed Boston-area relief efforts from his home. These national efforts spurred the local community. St. John gathered sixty prominent citizens at the Opera House to form the Central Relief Committee. It raised $533 that night.18

Despite Mayor Chase’s fears, many Exodusters found work in Topeka and other cities as mechanics, teamsters, laborers, and maids. Some worked as agricultural laborers or ranch hands in rural Kansas; others moved to black agricultural settlements, such as the Dunlop colony and Nicodemus, where they had mixed success as homesteaders. Robert Athearn poignantly described these impoverished black farmers who battled nature with their bare hands. “More than one of the Exodusters tried to dig out little circles of sod with hand shovels,” he wrote, “and to plant potatoes in the unfriendly soil below.” Most black newcomers ultimately adjusted and many became successful farmers, tradespeople, and mechanics.19

The Kansas Exodus ended almost as suddenly as it had begun, not because of white opposition or the advice of “representative colored men,” such as Frederick Douglass, that blacks remain in the South. Neither the suffering Exodusters experienced on the banks of the Mississippi and Kansas rivers nor the machinations of numerous swindlers who preyed on the gullibility of the freedpeople could arrest the movement. However, word filtered back that little free land remained in Kansas and that many Exodusters remained destitute a year after their arrival. Blacks in the South realized Kansas was not the “promised land.” Migration continued from Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas after 1880, but it never matched that of the spring and summer of 1879.20

Oklahoma Territory was the other major area for black emigration. The territory was created out of the western half of the Five Indian Nations lands returned to the federal government by the 1866 treaties. Between 1866 and 1885 various Indian tribes, including the Iowa, the Sac and Fox, the Comanche, the Cheyenne, and the Apache, were placed on reservations in Oklahoma Territory. Pressure from prospective settlers persuaded the federal government to reduce those reservations and open the “surplus lands” to homesteaders, resulting in the famous “run” for land claims on April 22, 1889. The subsequent opening of other former Indian lands in Oklahoma was one of the last opportunities for large-scale homesteading on public lands. A black territorial newspaper, the Langston City Herald, called it “the last chance for a free home.”21

For many African Americans, Oklahoma Territory was more than a homesteading opportunity. It represented a concerted effort to create towns and colonies where black people would be free to exercise their political rights without interference. In a nation of growing racial segregation and restriction, successful settlement in Oklahoma seemed a rare opportunities for African Americans to control their destiny in the United States. Kansans William Eagleson and Edwin P. McCabe became the two leaders in this movement. Eagleson, the editor of the Topeka American Citizen, was himself an emigrant to Kansas. By 1888 he had shifted his recruitment efforts to Oklahoma. In 1889 he founded the Oklahoma Immigration Association, headquartered in Topeka but with agents in the major cities of the South, where he hoped to attract a hundred thousand black settlers. Eagleson promised economic opportunity and freedom from racial restrictions: “Oklahoma is now open for settlement . . . the soil is rich, the climate favorable, water abundant and there is plenty of timber. Make a new start. Give yourselves and children new chances in a new land, where you will not be molested and where you will be able to think and vote as you please. . . . Five hundred of the best colored citizens have gone there within the last month . . . there is room for many more.”22

Eagleson’s effort met with some success. R. F. Foster, an association representative in the South, reported in April 1890 that seventeen hundred African American settlers had already left Atlanta for Oklahoma. In August a committee of three, representing some three hundred blacks from Mississippi, visited the territory to investigate immigration prospects, and in February 1891, forty-eight black Arkansans arrived in Guthrie, followed by two hundred prospective settlers from Little Rock. By the spring of 1891, when blacks from the South arrived in Oklahoma on “almost every train,” the territory had seven African American settlements.23

Edwin P McCabe, came to symbolize the Oklahoma emigration movement. Through most of the 1880s McCabe was committed to his adopted Kansas. After serving two terms as auditor, McCabe failed to win nomination for a third term. He nonetheless continued to support the Republican party and was closely aligned with Kansas Senators John Ingalls and Preston Plumb. When McCabe failed in his 1889 election bid for register of the Kansas Treasury, he moved to Washington, hoping to obtain an appointment from President Benjamin Harrison. During his months in Washington both friends and foes accepted the rumor that McCabe was campaigning to be appointed the first governor of Oklahoma Territory. Although Harrison was not impressed with the Kansas politician, McCabe allowed the rumor to persist. Employing the typical language of Oklahoma boosters, he declared the territory “the . . . paradise of Eden and the garden of the Gods.” But to the blacks growing restless under southern segregation and lynch law, he added a special enticement: “Here the negro can rest from mob law, here he can be secure from every ill of the southern policies.”24

The idea of a predominantly black Oklahoma inspired ridicule and condemnation outside the African American community. Oklahoma’s Democrats used the McCabe plan to brand all Republicans dangerous and unworthy of white support. When the territory’s Democrats met in convention at Kingfisher in 1892, they declared that a vote for a Republican was a vote for “negro domination, race mixing and race war.” The Vinita Indian Chieftain, a Native American newspaper, condemned the scheme to colonize Oklahoma with African American settlers, which it claimed was hatched by Kansas Senator Plumb during a visit to Guthrie in 1889. The newspaper commented on the irony of white “Oklahomaists” scheming to “take the land from the Indians only to have negroes take it from them.” But Republicans issued the worst rebuke. One angrily declared “if the negroes try to Africanize Oklahoma they will find that we will enrich our soil with them.” Another declared that if McCabe were appointed governor, he “would not give five cents for his life.”25

Undaunted, McCabe and his wife, Sarah, arrived in Oklahoma in April 1890 and joined Charles Robbins, a white land speculator, and Eagleson in founding Langston City, an all-black community about ten miles northeast of Guthrie, then the capital of Oklahoma Territory. Langston City was named after the Virginia black representative who supported emigration to Oklahoma and pledged support for a black college in the town. The McCabes owned most of the town lots and immediately began advertising for prospective purchasers through their contacts in the territory and through the Langston City Herald’s readers in Kansas, Arkansas, Texas, Louisiana, Missouri, and Tennessee. “Langston City is a Negro City, and we are proud of that fact,” proclaimed McCabe in the Herald. “Her city officers are all colored. Her teachers are colored. Her public schools furnish thorough educational advantages to nearly two hundred colored children.” The Herald also touted the Oklahoma prairie’s potential for growing superior cotton, wheat, and tobacco. “Here too is found a genial climate, about like that of southern Tennessee or northern Mississippi, a climate admirably suited to the wants of the Negro from the Southern states. A land of diversified crops where . . . every staple of both north and south can be raised with profit.” Edwin and Sarah McCabe’s promotions blended their political and economic objectives. A large black population in Oklahoma ensured McCabe’s political influence and the couple’s profit.26

By 1891 Langston City had two hundred people, including a doctor, a minister, and a schoolteacher. “People who scoffed at the idea of Negroes being able to build a town of their own,” the Herald reminded the skeptics in 1892, “[must] acknowledge that they were mistaken.” McCabe and other immigration promoters scrupulously encouraged prosperous blacks to settle in Langston City. For nearly a year between 1891 and 1892 the Herald ran a column titled “Come Prepared or Not at All.” The paper called for “active, energetic men and women with some money” who were “prepared to support themselves and families until they could raise a crop.” The Herald told the poor, “If you come penniless you must expect it to get rough.”27

African Americans comprised 6 percent of Logan County’s population in 1890. Thus McCabe realized that Langston City’s fate depended largely upon homesteading of nearby lands, starting with the Sac and Fox Reservation, opening on September 22, 1891. The Langston City Herald and Oklahoma Immigration Association agents spread the word throughout the South nearly a year prior to the opening. The Herald published advice on homesteading procedures: “Wherever you can find it, get 40, 80, or 100 acres of land and claim that as your homestead. As evidence that you do claim it, you must make some visible improvements. Drive a stake with your name on it, cut timber to lay the foundation of a house, do a little plowing or some other act that will show to others that you have occupied that particular piece of land.” The Herald urged these initial improvements be followed by more permanent ones and called on the prospective settlers to file claims promptly with the land office.28

Hundreds of blacks reached Langston City in time for the opening. Many of them were armed and reputedly ready to secure a home “at any price.” Their presence in the Cimarron Valley agitated local white cowboys and the Fox Indians, who threatened violence. Nonetheless prospective black homesteaders surged in. On September 21 five hundred black Texans stepped from a train in Guthrie and headed for the border of the new lands nine miles away. Half of them traveled by foot. On the day of the run some two thousand armed African Americans assembled at Langston City. Tensions mounted. Some whites on the northern line drove away would-be black settlers, and four miles south of Langston City black settlers exchanged gunfire with white cowboys. While checking on the progress of some prospective settlers, McCabe was fired upon by three white men, who ordered him to leave. He was rescued when armed blacks came to his assistance. Despite this violence, an estimated one thousand black families made successful claims on the Sac and Fox lands.29

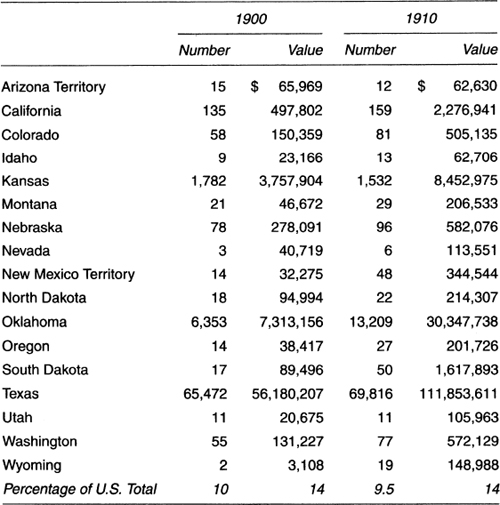

Thousands of blacks raced for the opening of the Cheyenne-Arapaho lands in 1892 and for the Cherokee Strip the following year. A day before the Cheyenne-Arapaho run, many of them massed on the sandbars besides the Cimarron River and along the ninety-eighth meridian, carrying their children and belongings on their backs. Just before the Cherokee Strip was opened, the Langston City Herald advised its readers: “Everyone that can should go to the strip . . . and get a hundred and sixty, all you need . . . is a Winchester, a frying pan, and the $15.00 to file.” A number of blacks did make the run on the strip and established the town of Liberty. One Oklahoma African American summarized the openings by declaring that “the whole Indian Territory will have been swallowed by the white man [but] many black men helped in the swallowing.”30

Black settlement in rural Oklahoma was much more extensive than in Kansas. By 1900 African American farmers in the territory owned 1.5 million acres valued at eleven million dollars. Many of these landowners were freedpeople or “state negroes” married to former slaves who acquired allotments in Indian Territory after the Dawes Act terminated communal landholding among the Five Nations. But an equal number of blacks gained homesteads in the various runs in Oklahoma between 1889 and 1895. W. G. Taylor, for example, arrived in 1892, claimed 160 acres, and, in accordance with homesteading requirements, received a deed to his property after living on the land for five years. Taylor and his wife, like many of their neighbors, lived in a dugout, grew vegetables, and raised chickens well into the 1930s. Roscoe Dungee arrived in Oklahoma from Minnesota in 1892 and found that “most everybody lived in dugouts.” Even after the initial settlement years the Dungee family and other farmers retained their dirt homes because of the safety they offered during tornadoes. The Dungees survived on vegetables, supplemented by prairie chicken, deer, rabbit, and quail.31

Eventually a thriving farming population arose that supported business owners and professionals. Blacks in Muskogee, Guthrie, Ardmore, Tulsa, and Oklahoma City operated cafés, grocery stores, saloons, rooming houses, and barber and blacksmith shops. They also occasionally owned clothing stores, jewelry shops, butcher shops, carriage stables, banks, and cotton gins. Black wheat and cotton buyers purchased crops from African American farmers while black doctors, dentists, lawyers, and druggists provided their varied services to numerous patrons.32

Yet the success of black farmers in Oklahoma and elsewhere in the region rested on a tenuous foundation of ample credit and rain. The absence of either could quickly spell disaster. Gilbert Fite did not have black farmers in mind when he wrote: “Rather than . . . establishing [sic] a successful farm and living a happy, contented life . . . [farmers] were battered and defeated by nature and ruined by economic conditions over which they had no control.” African American agriculturists knew well the conditions he described. Moreover, in Oklahoma Territory and elsewhere in the West their poverty precluded acquiring sufficient land to ensure success. By 1910 black landownership in Oklahoma had already peaked. Statistics tell the story: In 1910, 38 percent of black farmers had less than fifty acres, as opposed to 18 percent of white farmers. The average size of white farms was 50 percent greater than black holdings. Early-twentieth-century African Americans, like all Americans, were enticed by city life, but small landholdings in a region where large landholding was a necessity ensured an early exit from many western farms.33

African American migration to the Twin Territories (Indian and Oklahoma) produced thirty-two all-black towns. Generally settlers believed residence in these communities ensured economic and political control over their destinies. All-black communities were not unique to the twin territories. Historian Kenneth Hamilton has identified forty-six black towns in five western states and territories in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. These towns grew out of the desire of southern black emigrants to find some respite from racism. As one argued, “we are oppressed and disenfranchised. . . . Times are hard and getting harder every year. We as a people believed that Africa is the place but to get from under bondage we are thinking Oklahoma as this is our nearest place of safety.”34

|

|

California Abila Allensworth Bowles Victorville Colorado Dearfield Kansas Nicodemus New Mexico Dora Blackdom El Vado Oklahoma Arkansas Colored Bailey Boley Booktee Canadian Colored Chase Clearwater Ferguson Forman Gibson Station Grayson |

|

Langston City Lewisville Liberty Lima Mantu Marshalltown North Fork Colored Overton Porter Red Bird Rentiesville Summit Taft Tatum Tullahassee Vernon Wellston Colony Wybark Texas Andy Board House Booker Cologne Independence Heights Kendleton Mill City Oldham Roberts Shankleville Union City |

|

Adopted from Kenneth Marvin Hamilton, Black Towns and Profit: Promotion and Development in the Trans-Appalachian West, 1877–1915 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1991), 153.

The first black towns date back to antebellum times, when Seminole slaves settled in autonomous communities. After the Civil War, Creek and Cherokee freedpeople settled in such communities as North Fork and Canadian, which in time became attractive to blacks from neighboring states. Boley, however, became the most noted all-black town in the Twin Territories. Boley was founded in the former Creek Nation in 1904 by two white entrepreneurs, William Boley, a railroad manager, and Lake Moore, a former federal officeholder. They hired Tom Haynes, an African American, to handle town promotion. Fortunately Boley was located on the Fort Smith & Western Railroad in a timbered, well-watered prairie that easily supported agriculture familiar to most prospective black settlers. Still, the frontier character of the town was evident from its founding. Newcomers lived in tents until they could clear trees and brush to construct houses and stores. In 1904 Creek Indians and Creek freedmen frequently rode through Boley’s streets on shooting sprees. Several people died by gunfire until T. T. Ringo, a peace officer, killed some native “pranksters” outside a Boley church. Boley’s reputation for lawlessness persisted. In 1905 peace officer William Shavers was killed while leading a posse after a gang of white horse thieves who terrorized the town.35

By 1907 Boley had a thousand people, with two thousand farmers in its surrounding countryside. Churches, a school, restaurants, stores, fraternal lodges, women’s clubs, and a literary society attest to the economic and cultural development of the town. Booker T. Washington, in a town visit in 1908, explained its symbolic meaning for African Americans: “Boley . . . is striking evidence of the progress made in thirty years. . . . The westward movement of the negro people has brought into these new lands, not a helpless and ignorant horde of black people, but land-seekers and home-builders, men who have come prepared to build up the country. . . .”36

Boley’s spectacular growth was over by 1910. When the Twin Territories became the state of Oklahoma in 1907, the Democratic-dominated state legislature quickly disenfranchised black voters and segregated public schools and accommodations. Oklahoma was no longer a place where African Americans could escape Jim Crow. Black men continued to vote in town elections, but political control at the local level could not compensate for powerlessness at the courthouse or the state capital controlled by unsympathetic officials.

Moreover, after the initial years of prosperity, declining agricultural prices and crop failures gradually reduced the number of black farmers who supported the town’s economy. Even under ideal conditions, Boley and other black towns faced a challenge rampant throughout the rural United States: the lure of the city. The dreams of autonomy and prosperity that propelled an earlier generation to create Boley now encouraged the second generation to leave the town.37

No western state or territory held the emotional and economic appeal of Kansas or a potential for homesteads equal to Oklahoma Territory. Yet some black homesteaders ventured into the Dakotas, Nebraska, and Colorado. The Cleveland Gazette in 1883 reported that a colony of Chicago blacks organized under a “Mr. Watkins,” a Chicago firefighter, acquired “several thousand acres of land at Villard, in McHenry County,” Dakota Territory. A number of black agricultural colonies appeared in Nebraska between 1867 and 1889. The largest, a group of two hundred former Tennesseans, tried home-steading in Harlan County. On New Year’s Day 1884 one successful homesteader, I. B. Burton, wrote to a Washington, D.C., black news-paper from his new home near Crete, Nebraska, where another group of black settlers had bought land. He described how the settlers had pooled their resources, and he urged others to follow their example. “A large company can emigrate and purchase railroad lands for about half of what it would cost single persons, or single families. . . . Windmills are indispensable in the far west, and one windmill could be made to answer four or five farmers—each having an interest in it.38

African American Farms in the West, 1900, 1910

Source: U.S. Bureau of the Census, Negro Population, 1790–1915 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1918), 592.

Burton’s call went largely unanswered until the Kinkaid Homestead Act of 1904 threw open thousands of acres in the sand hills of northwestern Nebraska. Recognizing the land’s aridity, the federal government provided larger homestead claims of 640 acres. The first African American to file a claim, Clem Deaver, arrived in 1904. Other blacks, primarily from Omaha, soon followed, and by 1910, 24 families claimed 14,000 acres of land in Cherry County. Eight years later 185 blacks claimed 40,000 acres around a small all-black community near present-day Brownlee, originally named Dewitty for a local black business owner but later called Audacious. “The Negro pioneers worked hard,” recalled Ava Speese Day, who wrote of her childhood in the sand hills. “It was too sandy for grain so the answer was cattle. . . . We [also] raised mules [which] brought a good price on the Omaha market.” Yet in a pattern much like Oklahoma and Kansas, black farm families by the early 1920s had begun leaving for Denver, Omaha, or Lincoln. “Looking back, it seems that getting our [land] was the beginning of the end for us in Nebraska,” Day remembered. “There was one thing after another. . . . In March 1925, we left the Sand Hills for Pierre, South Dakota.”39

Dearfield, Colorado, was the last major attempt at agricultural colonization on the high plains. Dearfield was the idea of Oliver Toussaint Jackson, an Ohio-born caterer and messenger for Colorado governors. Jackson arrived in the state in 1887 and worked in Boulder and Colorado Springs as well as Denver. Inspired by Booker T. Washington’s autobiography, Up from Slavery, Jackson believed successful farm colonies were possible in Colorado. His faith in rural western settlement as racial uplift was shared by many prospective Dearfield settlers. One of them told a Denver Post reporter in 1909: “We realize the negro has little . . . chance in competition with the white race in the ordinary pursuits of city life. We want our people to get back to the land, where they naturally belong, and to work out their own salvation from the land up.”40

In 1910 Jackson and his wife, Minerva, filed a “desert claim” for 320 acres in Weld County, where the Dearfield colony was established. The claim attracted other investors, including Denver physician J. H. P. Westbrook, who suggested the name Dearfield. In late summer of 1910 forty-eight-year-old Jackson and his first recruit for the colonization venture, sixty-two-year-old construction worker James Thomas, set out from Denver by wagon. Seven hundred mostly middle-aged Denver women and men followed them to Dearfield over the next decade. The female and male settlers included former laborers, teamsters, janitors, coal miners, teachers, barbers, porters, maids, and waiters. Although they had little capital and virtually no experience in agriculture, all hoped to become dryland farmers. Jackson recalled the first settlers as “poor as people could be when they took up their homesteads. Some who filed on their claims did not have the money to ship their housegoods or pay their railroad fare. Some of them paid their fare as far as they could and walked the balance of the way to Dearfield. . . . Some of us were in tents, some in dugouts and some just had a cave in the hillside.”41

Settlers’ fortunes slowly improved. By 1915 the colonists had filed claims on eight thousand of the available twenty thousand acres in Weld County. One farmer optimistically wrote in 1915: “We planted oats, barley, alfalfa, corn, beans, potatoes of all kinds, sugar beets, watermelons, cantaloupes, and squash. Everything came up fine, then came the grasshoppers that almost cleaned us out. . . . We were not discouraged, however and last fall did some clearing for hay ground. . . . If we have no bad luck this year, our people will be self supporting by next fall.”42

Dearfield prospered during World War I. By 1917 Jackson had stopped recruiting settlers from Denver because all available land had been homesteaded. Record high agricultural prices generated a prosperity that many of the first settlers could not have imagined seven years earlier. “Dearfield . . . has laid a great foundation for the building of the wealthiest Negro community in the world,” wrote Oliver Jackson with both pride and typical booster hyperbole. A year later he added in a nationwide letter advertising the town, “There is no better location in the United States than Colorado to try on the garment of self government.”43

However, like Nicodemus, Boley, and other western agricultural settlements that preceded it, Dearfield eventually slid into oblivion. The colony’s population peaked at seven hundred in 1921 and fell sharply during the postwar agricultural depression. The lure of jobs in Denver, the colony’s inability to obtain water for irrigation, and the bleak countryside (one former resident recalled that “it was always the same—a lot of wind blowing—bad wind”) all contributed to the colony’s demise. By 1946 Dearfield’s only residents were Oliver T.Jackson and his niece Jenny, who had recently moved from Denver to care for him.44

Oscar Micheaux of Gregory County, South Dakota, became the most famous black homesteader on the northern plains, in part because he left accounts of his activities in autobiographical fiction, The Conquest and The Homesteader, the first of his seven novels. Born in 1884 on a farm near Murphysboro, Illinois, Micheaux worked as a Pullman porter before homesteading. When the federal government opened the eastern part of the Rosebud Indian Reservation to non-Indian settlement in 1904, Micheaux moved west from his Chicago home. He missed the spring lottery that distributed the lands (the federal government, learning from its experience in Oklahoma, decided to avoid a land rush) but nonetheless acquired a farm. “I concluded . . . [that] if one whose capital was under eight or ten thousand dollars, desired to own a farm in the great central west,” wrote Micheaux, “he must go where the land was . . . raw and undeveloped.”45

In 1913 Micheaux published The Conquest, a thinly veiled autobiography, followed four years later by his personal history of high plains farming, The Homesteader. After The Homesteader appeared, Micheaux lost interest in farming. By 1918 he had created the Micheaux Film and Book Company, which transformed The Homesteader into an eight-reel film. Micheaux left South Dakota for Chicago to film The Homesteader in the Selig Studio and never again lived in the state. He had launched the career that established him as the nation’s most prolific black filmmaker between the 1920s and 1940s, producing forty-five movies before his death in 1951 in Charlotte, North Carolina.46

Oscar Micheaux homesteaded and then turned away from the West, but the histories of two homesteaders, Robert Ball Anderson of Nebraska and James Edwards of Wyoming, provide a glimpse into the world of successful African American settlers. Robert Ball Anderson, born a slave in Green County, Kentucky, in 1843, joined the Union army in 1864 and spent three years of his enlistment in the West. In 1870 he homesteaded 80 acres of land in southeastern Nebraska. Low crop prices, drought, and grasshopper infestations forced him temporarily out of farming in 1881. After working as a Kansas farmhand, Anderson, now forty-one, moved to the Nebraska panhandle to start over. He took one of the first homestead claims in Box Butte County, where he built a two-room sod house for shelter. Despite the agricultural depression of the 1890s, Anderson continued to add to his holdings. By the end of the century he had acquired 1,120 acres of wheat and grazing land. “I lived alone, saved, worked, hard, lived cheaply as I could,” recalled Anderson in his autobiography, From Slavery to Affluence. By 1918 Anderson, now the owner of 2,080 acres, was by far the largest black landholder in Nebraska, and one of the most prosperous farmers in the state. Nine years later he wrote: “I am . . . old now, and can’t do much work. I have a good farm . . . and money in the bank to tide me over my old age when I am unable to earn more. . . . I am a rich man today, at least rich enough for my own needs.”47

James Edwards, born in Ohio in 1871, reached Wyoming in 1900, traveling west with his father to work as a coal miner near Newcastle. When he and his father were driven from the mines by Italian miners, Edwards herded sheep on a Niobrara County ranch. By 1901 Edwards had taken his first homestead claim, a ninety-acre parcel that became the center of a ten-thousand-acre ranch with two hundred cattle and one thousand sheep. Except for his skin color, Edwards looked and acted the part of the “classic Old West cowboy.” Tall, athletic, mustached, lanky, Edwards rolled Bull Durham cigarettes and, despite his wife’s disapproval, “got drunk” on whiskey on his visits to town.48

Like Anderson, Edwards lived in an overwhelmingly white community. His stock brand was the “sixteen bar one” representing, he claimed, the ratio of white men to black men in Niobrara County. Yet both farmers provided valuable work experience for black youth from as far away as Denver, Minnesota, Oklahoma, and Arkansas. Moreover, each in his own way earned the respect of neighbors. One neighbor wrote of Edwards: “All in all . . . he was a good man, and was liked in the community. . . . I have a lot of respect for any black man who invades a white territory, makes a living for himself, and builds a home as elaborate as his was on the prairie.”49

An influential minority of westerners made ranching their exclusive economic activity, giving rise to the twentieth-century image of the region as the nearly exclusive domain of cattlemen and cowboys. Sixty-one thousand ranchers, herders, and drovers worked in the range cattle industry in 1890. However, they comprised only 2 percent of the three million workers in western states and territories. By comparison the West had nearly nine hundred thousand farmers.50

If historians have exaggerated the number and influence of western cowboys, they have also erred in their estimates of African Americans in the industry. Early estimates placed the numbers of blacks in ranching at nine thousand. The 1890 census, however, listed the total number of black, Asian, and Native American stock raisers, herders, and drovers in the western states and territories at sixteen hundred. Black Texas cowboys, who were more numerous than in any other western state or territory, nonetheless constituted 4 percent of the total of Texas herders in 1880 and 2.6 percent by 1890. Overall, black cowboys were about 2 percent of the total in the West.51

Stock Raisers, Herders, Drovers, 1890

|

||

| Total | Total Nonwhite* | |

|

||

Arizona Territory |

2,712 |

148 |

California |

5,978 |

293 |

Colorado |

5,297 |

21 |

Idaho |

1,553 |

28 |

Kansas |

1,565 |

28 |

Montana |

4,458 |

34 |

Nebraska |

1,619 |

10 |

Nevada |

1,049 |

118 |

New Mexico Territory |

6,832 |

333 |

North Dakota |

693 |

1 |

Oklahoma Territory |

378 |

2 |

Oregon |

3,105 |

55 |

South Dakota |

886 |

21 |

Texas |

17,819 |

473 |

Utah |

2,418 |

8 |

Washington |

1,044 |

26 |

Wyoming |

4,147 |

32 |

*Also included Chinese, Japanese, Indians. |

||

|

||

Source: U.S. Bureau of the Census, Population of the United States, 1890, Part II (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1897), 532–626.

African American Stock Raisers, Herders, Drovers, 1910

|

||

| Stock Raisers | Stock Herders, Drovers | |

|

||

Arizona Territory |

5 |

16 |

California |

17 |

31 |

Colorado |

4 |

7 |

Idaho |

1 |

1 |

Kansas |

10 |

17 |

Montana |

1 |

9 |

Nebraska |

3 |

9 |

Nevada |

0 |

3 |

New Mexico Territory |

6 |

21 |

North Dakota |

0 |

0 |

Oklahoma |

14 |

32 |

Oregon |

4 |

6 |

South Dakota |

6 |

3 |

Texas |

48 |

406 |

Utah |

1 |

17 |

Washington |

1 |

3 |

Wyoming |

5 |

23 |

|

||

Source: U.S. Bureau of the Census, Negro Population, 1790–1915 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1918), 513–16.

While the number of black cowboys was smaller than previously assumed, census data nonetheless show them throughout the region. Numerous vignettes in newspapers, journals, biographies, and histories that briefly mentioned or described African Americans corroborated their presence in the range cattle industry. Typical of such accounts was J. Frank Dobie’s description of Pete Staples. A former Texas slave, Staples after the Civil War worked along the Rio Grande with vaqueros, in both northern Mexico and west Texas, married a Mexican woman, and joined the first cattle drives to Kansas. For two decades Jim Perry was one of a number of black employees of the three-million-acre XIT Ranch in the Texas Panhandle. He once declared, “If it weren’t for my damned old black face I’d have been boss of one of these divisions long ago.” Charlie Siringo recalled a visit to Texas cattle baron Abel (“Shanghai”) Pierce’s headquarters near Matagorda in 1871. “There were about fifty cowboys at the headquarter ranch,” Siringo wrote, including “a few Mexicans and a few negroes. . . . The negro cook . . . drove the mess-wagon. . . .” Mississippi-born slave Bose Ikard was lifted from anonymity by the fulsome praise given him from his employer, Texas cattleman Charles Goodnight. “Ikard surpassed any man I had in endurance and stamina,” wrote Goodnight. “He was my detective, banker, and everything else in Colorado, New Mexico, and the other wild country I was in. . . . We went through some terrible trials during those four years on the trail. . . . [He] was the most skilled and trustworthy man I had.” Print Olive, a transplanted Texan in western Nebraska, left no flowing tribute for his employee and constant companion James Kelly but was equally grateful. Olive, wounded three times in an Ellsworth, Kansas, saloon by Texas cowboy Jim Kennedy, was about to be killed when Kelly shot Kennedy.52

One black cowboy’s brief personal narrative has survived. Daniel Webster (80 John) Wallace, born near Inez, Texas, in 1860, eventually became the state’s most successful black rancher. Before his ascent into the ranks of cattlemen, Wallace was a west Texas cowboy who started working at the age of sixteen in Lampasas County. By 1881 he had begun working for rancher Clay Mann, who originated the “80” brand, the basis of Wallace’s nickname. Wallace described life on the cattle frontier, where everyone “slept on the ground in all kinds of weather with our blankets for a bed . . . a saddle for a pillow . . . and gun under his head.” He recalled standing guard on stormy nights “when you couldn’t see what you were guarding until a flash of lightning,” or where a rattlesnake might be “rolled up in your bedding” or where cowboys were awakened by the “howl of the wolf or holler of the panther.”53

We don’t know if Wallace participated in the post–Civil War cattle drives, but other African Americans trailed longhorns from central Texas to railheads in Abilene, Dodge City, Denver, Cheyenne, or northern pastures in Montana. William G. Butler in 1868 drove a herd of cattle to Abilene with a crew of fourteen that included three Chicanos, nine whites, and two black drovers, Levi and William Perryman. R. F. Galbreath arrived in Kansas in 1874 leading a crew of four whites and three blacks, while Jim Ellison went up the trail in the same year with an all-black crew. In 1885 Lytle and Stevens sent north a herd of two thousand steers bossed by a black Texan, Al Jones.54

Since the trail drives began during the Reconstruction era, it would be naive to assume no racial tension existed between black and white Texans. The cowboys’ trail drive rosters usually included names for white drovers but made references to “nigger” or “colored” hand for African Americans. During an 1878 Texas to Kansas trail drive, Poll Allen, the principal drover, directed a black cowboy to eat and sleep away from the rest of the crew. Finally Allen ran the man off by shooting at him. Instances of outright exclusion from the trail herd were rare, but discrimination in work assignments was common. John M. Hendrix, a white rancher and former drover, inadvertently described that discrimination in an early tribute to African American cowboys. Blacks “were usually called on to do the hardest work around an outfit,” such as “taking the first pitch out of the rough horses . . .” recalled Hendrix. “It was the Negro hand who usually tried out the swimming water when a trailing herd came to a swollen stream, or if a fighting bull or steer was to be handled, he knew without being told that it was his job.” On cold, rainy nights blacks would stand “a double guard rather than call the white folks. . . . These Negroes knew their place, and were careful to stay in it.”55

Yet such nostalgia often obscured complexities and contradictions of the racial order on the high plains. Interdependence on the trail undermined arrogant displays of racial superiority or overt discrimination. Men on trail drives spent long hours facing common dangers. Black and white wages were equal although vaqueros were paid one-third to one-half the wages of the other cowboys. The workplace racism that permeated plantations in east Texas or the Old South did not exist on the plains.56

Nor were racial sentiments openly expressed in the most famous end-of-the-trail town, Dodge City, Kansas. Kansas’s reputation for racial toleration and the promise of hundreds of black cowboys spending wages in the saloons, restaurants, hotels, brothels, and other businesses along notorious Front Street encouraged social mixing in this raw new town, founded in 1875. White and black drovers shared hotel rooms, card games, cafe tables, and on occasion jail cells. One attempt to exclude blacks from a hotel was recalled years later precisely because of its failure. When a hotel clerk in the Dodge House told a black cowboy that no rooms were available, the drover drew what the frightened clerk described as the “longest barreled six-shooter he had ever seen” and waved it in his face, saying, ‘You’re a liar!’ ” The clerk quickly rechecked his roster and found a suitable room.57

Texas’s enormous African American population, coupled with its role in founding the nineteenth-century range cattle industry, guaranteed the state the largest black cowboy population. But African American cowboys worked elsewhere in the West. In 1883 Theodore Roosevelt admired the skills of a Texas-born Dakota Territory drover known only as Williams who broke horses on a neighboring ranch. Four African American cowboys in eastern New Mexico found themselves embroiled in the infamous Lincoln County range war of 1878, which introduced William Bonney, or Billy the Kid, to the American public. Three cowboys, George Washington, George Robinson, and Zebrien Bates, sided with the supporters of Alexander McSween and Bonney, who styled themselves Regulators, while John Clark worked for businessman-rancher Lawrence Murphy. New Mexico trail drover George McJunkin, who became a ranch foreman in Union County, is remembered primarily for his 1908 accidental discovery of the Folsom archaeological site that established the presence of humans on the North American continent during the ice ages. In neighboring Arizona Territory, John Swain and John Battavia worked for former Texas rancher John Slaughter, who had established a new ranch near Tombstone in 1884. Men such as Thornton Biggs, who worked in northern Colorado, and Henry Harris, another former Texan who became a foreman on the Elko County ranch of Nevada Governor John Sparks at the turn of the century are examples of black range workers throughout the West.58

Some African American cowboys were lifted from obscurity by irresponsible behavior or untimely death. In 1870 a black cook from Texas “shot up” Abilene, Kansas, while celebrating the end of a successful trail drive. He obtained the dubious distinction of becoming the first occupant of the new city jail and its first escapee when fellow drovers rescued him. Another black man, an innocent observer of a gambler’s quarrel, was the first person killed in Dodge City. His death and subsequent murders prompted town merchants to form a vigilance committee and to hire a series of marshals, of whom Wyatt Earp and Bat Masterson were the most famous. The Trinidad (Colorado) Daily Advertiser reported in 1883 that a San Miguel, New Mexico Territory, black drover, George Withers, “wantonly and without provocation shot and killed George Jones (colored),” another ranch hand on the Canaditas cattle ranch, and then fled for Texas, pursued by a “posse of cowboys.” The violent death of a black cowboy in Trinidad, Colorado, in 1887 elicited editorial comment from Field and Farm, a Denver journal: “Lawson Fleetwell . . . a bad man from the Indian nation, was shot and killed by an officer in Trinidad on Monday night. Fleetwell was in a gambling institution and got up a gun play in which he himself was killed. The cowboy seems to be keeping up his reputation this year as well as ever, and the mortuary reports are as entertaining as usual. It’s generally the cowboy that gets the worst of the racket and he is not such a successful bad man as he has been pictured.”59

A chasm separated the “cattleman” and his “cowboy” employees. Yet a few African Americans bridged that divide to become successful ranchers. Soon after the Civil War a Texan, Felix Haywood, and his father rounded up unbranded cattle along the San Antonio River for a white rancher who paid them in land that became the Haywood ranch. Henry Hilton and Willis Peoples owned ranches near Dodge City in the 1870s while Ben Palmer became “one of the heaviest taxpayers of Douglas County, Nevada,” in the same decade. Isaac and Lorenzo Dow, two brothers born into slavery in Arkansas, arrived in Nevada in 1864 and acquired cattle ranches near Caliente, which they worked until 1900. The most successful western cattleman, however, was Daniel Webster (“80 John”) Wallace, who made his first land purchase in Mitchell County, Texas, in 1885 while working as a cowboy. By the time of his death in 1939 the Wallace ranch had grown to 10,240 acres.60

Philip Durham and Everett Jones offered a succinct reason for the twentieth-century invisibility of nineteenth-century black drovers: “When the West became a myth . . . the Negro became the invisible man. . . . There was no place for him in these community theatricals. He had been a real cowboy, but he could not easily pretend to be one.” This statement offers a partial explanation. Without doubt early Wild West shows, dime novels, and later more substantive literature, such as Owen Wister’s 1902 novel The Virginian, established the white Anglo-Saxon as the cowboy archetype of the imagined West. Hundreds of subsequent books, films, and television episodes, advertising strategies, and toys reinforced the stereotype. But the “whitening” of the cowboy actually occurred in the late nineteenth century with the careful manipulation of the image by drovers and ranchers themselves, who extolled the virtues of white supremacy and racial purity.61

Theodore Roosevelt’s description of the cowboys he worked with in the 1880s, for example, simultaneously exposed both the multicultural dimensions of the range cattle work force and the prejudices (including his own) toward those who were not white: “Some of the cowboys are Mexicans who generally do the actual work well enough but are not trustworthy . . . they are always regarded with extreme disfavor by the Texans in an outfit, among whom the intolerant caste spirit is very strong. Southern-born whites will never work under them and look down upon all colored or half-caste races. One Spring I had with my wagon a Pueblo Indian, an excellent rider and roper, but a drunken, worthless, lazy devil; and in the summer of 1886 there were with us a Sioux half-breed, a quiet, hard-working, faithful fellow, and a mulatto, who was one of the best cow-hands in the whole round-up.62

The elevation of one group often occurred alongside the denigration of others who at the time were significant elements in the drover work force. “The Greasers are the result of Spanish, Indian and negro miscegenation,” wrote Joseph McCoy in 1872 in his assessment of the vaquero, “and as a class are unenterprising, energy-less and decidedly at a stand-still so far as progress, enlightenment, civilization, education, or religion is [sic] concerned.”63 Despite the considerable skill, dedication, and innovation they brought to the range cattle industry, it was increasingly clear even in the 1870s and 1880s that the racial dynamics of the period precluded the entry of black, brown, or red drovers into the pantheon of cowboy heroes.

“The process of moving” wrote George W. Pierson in 1973, “alters the stock, temperament, and culture of the movers, not only by an original selection but on the road as well as also at journey’s end.”64 Pierson’s words apply particularly to the nineteenth-century black western migrants. Their migration initiated the process of their own self-transformation. They adapted to the new physical environment, new customs, and new neighbors. But these settlers, full of hope, expectation, and promise, also modified their new region. Convinced that the political culture in the post–Reconstruction South offered no hope for equitable citizenship, late-nineteenth-century African Americans summoned all their energies to fight discrimination in their new homes. If they failed, the prospect for creating better lives for themselves and their children was lost forever.