In 1913 W. E. B. Du Bois embarked on a promotional tour through Texas, California, and the Pacific Northwest. The tour signaled recognition of the West’s crucial role in the burgeoning campaign for racial justice and equality. Du Bois assured his audiences that the NAACP was committed to fighting injustice locally, regionally, and nationally. The black West would not be ignored.1

Du Bois’s tour also recognized the importance of western urban African American communities. By the second decade of the twentieth century the center of African American life in the West was urban. African American urbanites outnumbered rural residents in every western state except Texas and Oklahoma. Even there the political, economic, and cultural center of black life lay in Houston and Dallas, Oklahoma City and Tulsa long before most black Texans or Oklahomans became urbanites. The fate of the average twentieth-century black westerner would be determined on city streets.

Black Los Angeles emerged during this period as the largest urban black western community in California. By the second decade of the twentieth century it had eclipsed San Francisco and Oakland as the center of black politics and business in California, a transition symbolized by the 1918 election of Frederick M. Roberts as the first African American assemblyman in the state and by the rise of the state’s largest black business, the Golden State Mutual Insurance Company. African American communities in Houston and Dallas rivaled Los Angeles in size, if not in fame. Denver’s black community continued its steady growth, while a World War I-era influx of African American migrants from the South doubled Omaha’s black population.2

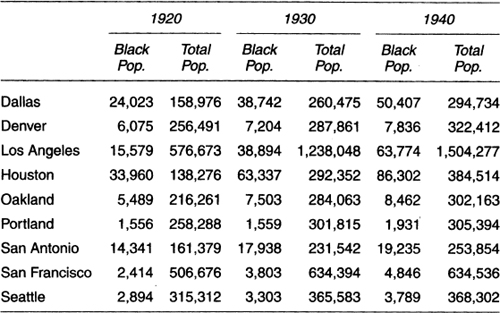

African American Urban Population in the West, 1920–40

Black Population in Cities of 250,000 or More in 1940

Sources: U.S. Bureau of the Census, Fourteenth Census of the United States, vol. 2, Population, 1920 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1922), 47, and U.S. Bureau of the Census, Sixteenth Census of the United States, 1940, Population, vol. 2, Characteristics of the Population (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1943), part 1, 629, 636, 657, 787; part 5, 1041; part 6, 1026, 1044, 1053; part 7, 400.

African Americans moved to other western cities, notably Seattle and Portland in the Pacific Northwest; Phoenix, Tucson, and San Diego in the far Southwest; and Wichita, Oklahoma City, and Tulsa on the southern plains. Black Tulsa’s rapid growth during World War I, prompted by oil discoveries in the region, gave rise to an enterprising, successful population that chafed under southern-inspired racial restrictions. Their success heightened black-white tensions and sparked the Tulsa race riot of 1921, an orgy of white violence on June 1 that took thirty lives and destroyed eleven hundred homes and most businesses in Deep Greenwood, Tulsa’s African American district.3

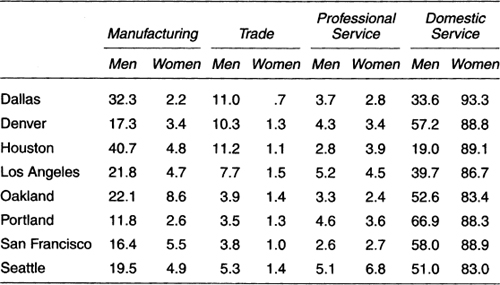

Nineteenth-century urban employment patterns continued virtually unchanged until World War II. In 1930 most African American males in San Francisco, Oakland, Denver, Portland, and Seattle were servants. Only in Houston did male workers in manufacturing outnumber those in domestic service. For black women in the largest western cities, domestic service dominated, with percentages ranging from a low of 83 percent in Seattle to a high of 93 percent in Dallas. This employment concentration prompted the Northwest Enterprise, Seattle’s black newspaper, to declare in 1927: “Colored men should have jobs as streetcar motormen and conductors. [Black women] should have jobs as telephone operators and stenographers. . . . Black firemen can hold a hose and squirt water on a burning building just as well as white firemen. We want jobs, jobs, after that everything will come unto us.”4

C. L. Dellums, vice-president of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, recalled work opportunities soon after he came to the San Francisco Bay Area from Texas in 1923. “I had been around here long enough to realize there wasn’t very much work Negroes could get.” African American workers could either “go down to the sea in ships or work on the railroads.” Fourteen years later Kathryn Bogle discovered similar limitations when she began to search for employment after graduating from a Portland high school. “I visited large and small stores. . . . I visited the telephone company; both power and light companies. I tried to become an elevator operator in an office building. I answered ads for inexperienced office help. In all of these places I was told there was nothing about me in my disfavor except my skin color.” Bogle then described how several employers who refused to hire her downtown offered her work, “as a domestic . . . where her color would not be an embarrassment.”5

Source: U.S. Bureau of the Census, Fifteenth Census of the United States, 1930, Population, vol. 4, Occupations by States (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1933), 199–210, 244–46, 1370–72, 1585–87, 1593–96, 1709–11.

One occupation—motion-picture actor—was exclusively western. By the second decade of the twentieth century the motion-picture industry centered in Hollywood, California, as Los Angeles–area studios gained nationwide control over production and distribution of films. African Americans had been film actors in the pre-California days of motion pictures and often had sensitive, nonstereotypical roles in pre–World War I films. They hoped to continue working in the industry after it concentrated in southern California. But film moguls relegated black employees to service jobs and black actors to roles that reflected their subservient status in the work force. From 1915 to 1920 roughly half the black roles reviewed by Variety were maids, butlers, and janitors. In the 1920s menial roles reached 80 percent and remained there until the 1930s, when such performers as Lena Horne, Cab Calloway, and Louis Armstrong played themselves in films directed toward black audiences. Art ruthlessly imitated life in the nation’s film capital.6

Virtually no one inside the studios challenged these early stereotypes forcing black actors to accept demeaning roles to “build ourselves into” the movie industry, as law school student-turned-actor Clarence Muse described it. A few actors, such as Paul Robeson, pursued careers abroad, while Louise Beavers and Hattie McDaniel plunged into community service or sponsored lavish parties to distance themselves from their portrayals as faithful servants. Yet the most successful film performer of the period, Stepin Fetchit, personified Hollywood’s negative characterizations of African Americans.7

Born Lincoln Theodore Monroe Andrew Perry in 1902 in Key West, Florida, Stepin Fetchit (the stage name derived from a vaudeville comedy team he formed with Ed Lee called Step and Fetch It) arrived in Hollywood in the early 1920s. When a Fox talent scout spotted him, he was given a successful screen test, and his career began. By the end of the 1920s he alone among African American actors had achieved feature billing and regular work. Between 1929 and 1935 he appeared in twenty-six films. Regardless of the script or setting, Fetchit’s character was usually a shuffling, superstitious, subservient black man. Many white moviegoers easily accepted Fetchit’s portrayals as African American “comic relief” in action-oriented films. Black audiences, however, were deeply ambivalent about his success. Many admired Fetchit’s wealthy lifestyle, symbolized by his multiple homes and servants and his champagne pink Cadillac, which regularly cruised Central Avenue. Yet off-screen antics, such as insisting reporters publish his interviews “in my dialeck,” indicated his failure to distinguish between his film portrayals and real-life persona. By the end of the 1930s Fetchit’s extravagant lifestyle had bankrupted him, and NAACP criticism of his portrayals ended his career.8

Meanwhile hundreds of black extras seeking careers in film lived precariously. Unlike Fetchit, these actors had no agents and did not haunt casting offices. Instead they clustered along Central Avenue, waiting for a casting director to drive by and choose an especially attractive woman or man to try out as an extra—often a slave in a plantation musical or a native in a jungle adventure. The prospect of earning up to $3.50 per day in a feature film drew hundreds of bit players into motion pictures ranging from D. W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation through David O. Selznick’s Gone with the Wind. As film historian Thomas Cripps notes, white actors were sometimes defeated by this system, but blacks never won.9

African American professionals and entrepreneurs served working-class residents in every western city. By 1915 nearly four hundred black Houston businesses served an all-black clientele. Black Los Angeles had fewer but more high-profile businesses, which generated enormous pride among the city’s African Americans and occasional comment from outsiders. Chandler Owen, Harlem resident and editor of the Messenger, declared Central Avenue a “veritable little Harlem in Los Angeles,” after a 1922 speaking tour. His assessment was based on the concentration of businesses and fashionable homes on “the Avenue.” Along a twelve-block section of Central Avenue could be found black-owned theaters, including the Angelus, which advertised itself as “the only show house owned by Colored men in the entire West,” savings and loan associations, automobile dealerships, newspaper offices, and retail businesses. The “Avenue” was also home to the Golden State Mutual Life Insurance Company and the Hotel Somerville (later the Dunbar Hotel), which became nationally famous after NAACP delegates stayed there during the organization’s 1928 national convention. Four stories tall, the Somerville, at Forty-first Street and Central Avenue, had one hundred rooms, sixty with private baths. In 1929 Dr. H. Claude Hudson, a prominent dentist and president of the local NAACP, built the Hudson-Liddell Building also at Forty-first and Central. The building, designed by African American architect Paul Williams, soon became the “symbol to black Angelenos of what was possible in Los Angeles.”10

In cities with small African American populations, such as Denver, Seattle, and San Francisco, black businesses struggled against intense competition from other people of color. In Seattle, for example, those blacks who resented white storeowner attitudes were eagerly courted by Asian entrepreneurs. Japanese and Chinese restaurants welcomed working-class black customers. One Asian restaurant owner developed a specialized menu of soul food to entice black porters and ship stewards. Occasionally Asian and black stores vied for the support of black community residents in a contest that pitted ethnic loyalty against perceptions of superior service. Margaret Cogwell, a black Seattle grocery store owner who lost her competition with an Asian grocer across the street, bitterly remarked: “The Negroes were always coming to the Japanese right across from me, and they’d go there and buy the same milk and bread . . . from the Japanese. Mine wasn’t good enough even though it was delivered the same time and everything.” Cogwell closed her store and left Seattle in 1919. Cogwell’s Japanese competitor had access to a regional distribution network that included Japanese wholesalers, other Japanese grocers, and Japanese farmers. Nonetheless her loss was painful when it appeared race disloyalty was responsible for the store’s failure.11

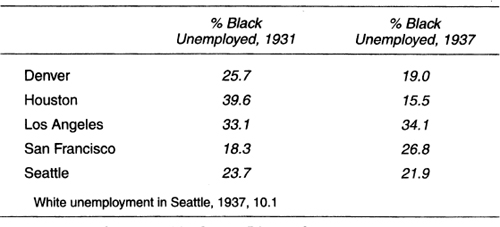

The Great Depression ravaged Western black communities throughout the 1930s. In Houston in 1931 black unemployment approached 40 percent compared with 17 percent for white workers. One of every three black workers in Los Angeles was unemployed in 1931, and one of every four in Denver and Seattle. The unemployment burden African American workers assumed prompted the Colorado Statesman to ask in 1933: “Is [the Negro] not an American citizen and entitled to share and share alike? . . . Although he is perfectly willing to take his chances, he is not given a chance. . . . He is, in truth and deed, the forgotten man. . . .”12

Statistics cannot completely convey the sense of loss and despair. Seattleite Sara Oliver Jackson remembered that during the early 1930s, “There wasn’t any particular jobs you could get, although you knew you had to work. So, you got a domestic job and made $10.00 a month, ’cause that was what they were paying, a big 35 cents a day. . . .” William Pittman, a San Francisco dentist unable to continue his practice, worked for eighty dollars per month as a chauffeur. His wife, Tarea, a 1925 University of California graduate, concluded that race discrimination added to the family’s declining economic fortunes. “I am unable to find work,” wrote Tarea Pittman, “. . . on account of my race.” One unidentified Portland woman recollected, “We were without work for well over a year. I did a number of things to help bring in money, and my husband worked for fifty cents a day shoveling snow down at the [Portland] Hotel. . . . People were just. . . trying to make it.”13

Black westerners turned to community self-help projects. Churches from Texas to Washington collected clothing and food and provided the homeless with temporary shelter. Father Divine and Daddy Grace helped some of Los Angeles’s destitute. When Phoenix relief agencies refused to aid impoverished African Americans, local blacks formed the Phoenix Protective League, which joined forces with black fraternal orders to provide assistance. In 1931 black churchwomen in Houston organized soup lines and dispensed food while in Richmond, California, Beryl Gwendolyn Reid single-handedly cooked “big pots of beans” to “feed all the people who were hungry.” Denver politician and nightclub owner Ben Hooper organized groups of World War I veterans to hunt jackrabbits, which were then distributed as food to needy families. Despite such valiant efforts, in 1931 many black community leaders agreed with Seattle Urban League director Joseph S.Jackson, who reported to New York that “blacks had supported themselves as long as they were able. . . .” They, and the nation, increasingly looked to the local, state, and federal government to address their plight.14

Even New Deal agencies did not guarantee public employment or relief. Willis Johnson, an unemployed black worker, moved to Houston from Louisiana during the Great Depression. He told an interviewer, “Relief is the only thing that I know anything about, and about all I know about that is that I have never been able to get any of it.” Johnson’s view was confirmed by Lorena Hickok, a “confidential investigator” for FDR’s adviser Harry Hopkins. Traveling across the nation in 1934, Hickok gave firsthand accounts of relief efforts. She reached Houston in April and wrote: “At no time . . . since taking this job, have I been quite so discouraged as I am tonight. Texas is a Godawful mess . . . relief in Houston is a joke.” New Deal agencies operating in Texas, including the National Recovery Administration, the Civil Works Administration, and the Works Progress Administration, discriminated against local blacks, prompting the Houston Informer, at first a supporter of the New Deal, to conclude in 1936, “Texas Negroes don’t benefit much one way or the other whether Roosevelt or Landon is in.”15

Unemployment in the Black Urban West, 1931, 1937

Sources: U.S. Bureau of the Census, Fifteenth Census of the United States: 1930, Unemployment, vol. 2 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1932), ch. 5, The Special Census of Unemployment, January 1931,” Table 2; U.S. Bureau of the Census, Census of Unemployment, 1937: Final Report on Total and Partial Unemployment, vols. 1, 3 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1938), Table 1. Gainful worker totals for 1931 were used to determine 1937 unemployment rates. Unemployment percentages for 1937 are based on the combined “totally unemployed” and “emergency workers” categories as percentage of population, 1930, age fifteen to seventy-four.

The one exception in the otherwise dismal treatment blacks received from New Deal relief agencies was the state’s National Youth Administration programs under twenty-seven-year-old Lyndon B. Johnson, who was selected as the first state director in September 1935. Johnson resisted pressure from national NYA officials to integrate the state advisory board, declaring that if he followed such a course, he would be “run out of Texas.” However, he did appoint an all-black advisory board and carefully weighed their suggestions. Moreover, he covertly reallocated funds from white to more needy black programs and created the Freshman College Center, a forerunner of Upward Bound, which brought to college campuses impoverished but academically capable students. Fifteen of the twenty programs in the state served black youth, giving them the support and incentive to enter college. Johnson’s efforts on behalf of black youth in a conservative state won accolades from African American government officials, including Mary McLeod Bethune and Robert C. Weaver. Bethune, director of the NYA Office of Negro Affairs and the ranking black appointee in the Roosevelt administration, condemned Johnson’s refusal to place an African American on the state NYA Advisory Board. Nonetheless she praised his other efforts and predicted, “He’s going to go places. He’ll be a big man in the country.” Weaver (whom President Johnson would appoint, in 1965, the first black cabinet officer) declared the young Texas NYA director “. . . was shocking some people up on [Capitol] Hill because he thought that the National Youth Administration benefits ought to go to poor folks. . . . To make matters worse, he was giving a hell of a lot of this money to Mexican-Americans and Negroes.” The future president did not act out of political expediency, since few blacks in Texas in the 1930s could vote. Instead his efforts demonstrated a genuine commitment to extend to blacks their share of the National Youth Administration allocations.16

Generally other western blacks fared better than Texas’s African Americans in getting federal support. Of Phoenix’s blacks, 51 percent (as opposed to 59 percent of the Mexican Americans and 11 percent of the Anglos) were on relief in 1933, a statistic revealing both easier access to government assistance than their Texas counterparts and the level of African American poverty. In December 1933, 160 black men earned eighteen dollars per week while working on the South Platte River flood control project sponsored by the Public Works Administration, prompting the Colorado Statesman to declare, “The Negro population cheerfully relishes their portion of the employment.”17

California’s blacks also fared well in their access to relief. San Franciscans received a disproportionate amount of relief or public employment. Women used public works programs to upgrade their skills away from domestic service. Black workers throughout the state were particularly successful with the Works Progress Administration and the National Youth Administration. Much of the success stemmed from the activities of Vivian Osborne Marsh, who headed the state’s Division of Negro Affairs. Marsh, a friend of Mary McLeod Bethune, used the network of the California Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs to attract more than two thousand black youths into the NYA between 1935 and 1941. Her efforts allowed four hundred African American college and graduate students to complete their education. Moreover, over one thousand women and men received training in sheet metal, machine, and radio and aircraft production and repair that served them well in the state’s World War II defense plants.18

The Great Depression encouraged leftist activism, which in turn assisted black westerners. The political left, including Communist-inspired popular front organizations, such as the Unemployed Citizens League, League of Struggle for Negro Rights, National Negro Congress, and International Labor Defense, mounted civil disobedience campaigns to confront racial discrimination in the region’s cities. In March 1930 500 mostly black women and men descended on Houston’s city hall in a Communist-organized demonstration to demand emergency unemployment relief and the abolition of racist legislation. Two years later in Phoenix the International Defense League and the Afro-American League sponsored a march to the state capitol to demand an end to discriminatory pay scales for black state workers and direct relief for needy families. In July 1932 Communists in Denver organized 150 African Americans to desegregate Smith Lake in South Denver, a public swimming area. In 1934, 700 Dallas activists organized an eleven-day city hall “sit-in” protesting cuts in federal WPA jobs for the area. Such demonstrations rarely gained their immediate objectives. They did introduce small western communities to “direct action” and brought together working-class people of various races over social justice issues.19

Like eastern black voters, Depression-era African American westerners embraced the Democratic party. This transition was encouraged by white liberal politicians, such as the members of the Washington and Oregon Commonwealth federations, which represented the left-liberal wing of the Democratic party. The WCF sponsored black Democratic clubs and opposed discriminatory state laws, while the OCF pushed for a state civil rights act in the 1930s. In a 1938 letter to NAACP Executive Director Walter White, Edgar Williams, a Portland branch official, declared the OCF “the only group of any political importance which has interested itself in [African American] problems. . . .”20

California’s black voters gravitated toward the Democratic party in the late 1920s through political organizing by Titus Alexander, John W. Fowler, and Dr. J. Alexander Somerville. In 1934, when Republican Frederick Roberts, who had served sixteen years in the state assembly, was defeated by a twenty-seven-year-old Democrat, Augustus Hawkins, a new political era began in the state. Hawkins represented the south-central Los Angeles assembly district until 1962, when he became the first African American member of Congress from California. With his ties to unions and leftist politicians, Hawkins personified an emerging political nexus of liberals, labor, and blacks in the Roosevelt coalition. Colorado’s black voters, however, were attracted to the Democrats by Denver saloon owner Ben Hooper, the “Mayor of Five Points.” Hooper forged an alliance with popular Denver Mayor Benjamin F. Stapleton in the early 1920s and through traditional big-city patronage dominated political life in Denver’s African American community during most of the interwar years.21

Most Texas and Oklahoma Democratic leaders remained steadfastly white supremacist in the 1930s and thus attracted little black support. San Antonio Representative Maury Maverick, who favored antilynching legislation and abolishing the poll tax, was the one notable exception. Maverick’s progressive stand began to attract the attention of African Americans across the state. However, his opposition to black San Antonio political boss Charles Bellinger kept Maverick from getting the support of the only major black Texas voting constituency in pre-World War II Texas. Bellinger, a real estate entrepreneur and gambler, in the 1920s forged a deal with San Antonio’s Latinos and the white-led political machine. In exchange for increased public services—parks, water lines, and street paving—Bellinger delivered a bloc of approximately eight thousand votes. As one historian claims, “Bellinger was able to secure from the . . . machine what could not be obtained through a democratic system crippled by racism.” Unique in Texas at the time, Bellinger’s machine demonstrated how blacks and Latinos could achieve leverage in a hostile political system. Elsewhere in the state Antonio Maceo Smith and Reverend Maynard H.Jackson, Sr., of Dallas organized the Progressive Voters League, which challenged the all-white primary system and developed a black constituency in the Democratic party. No white Oklahoma Democratic politician spoke out against racial injustice in the 1930s as Maury Maverick had in Texas, but influential African Americans, such as A. J. Smitherman, editor of the Tulsa Star, and Isaac W. Young, president of Langston University, began in the 1920s to persuade blacks to support Democratic candidates. By 1932 most African American voters in the state had made the transition.22

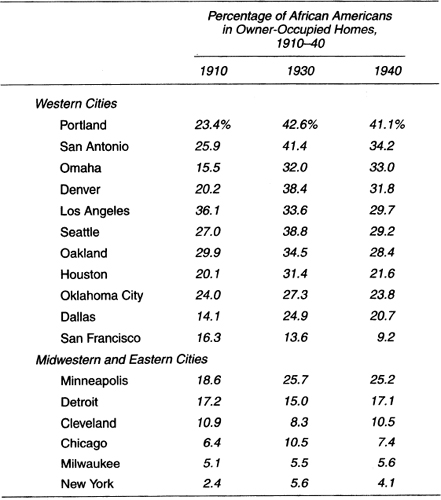

Despite economic difficulties a number of western African American urbanites purchased homes. Compared with the Northeast and Midwest, western cities (with San Francisco the notable exception) usually had high levels of black homeownership. Los Angeles led the way with a “bungalow boom” during the first two decades of the twentieth century. Along Central Avenue four or five-bedroom “California cottages” advertised for nine hundred to twenty-five hundred dollars and usually sold for one hundred dollars down with monthly payments of twenty dollars. Promotional ads occasionally described suburban areas such as Sierra Madre, where those who wanted a “splendid chance . . . for steady work [and a] fine climate” could purchase half acre lots or Eureka Villa, near Saugus, which advertised building lots for as little as seventy-five dollars. L. G. Robinson, a city custodian and Georgia migrant who arrived in Los Angeles in 1912, bought several lots on the edge of the city that he sold for a profit of several thousand dollars. Gracie Hall, a female domestic, proudly described the purchase of her first residential lot in a 1914 letter to Booker T. Washington. One anonymous black woman explained the success of her husband and herself as real estate entrepreneurs in a 1934 interview: “My parents were slaves and didn’t leave us anything but the desire to get ahead in life. We now own eight houses. How did we get so much property? Why, we worked for it. I ran a hand laundry and my husband worked for the city.” By 1924 black realtors proudly advertised Los Angeles as having one of the nation’s highest percentages of homeowners. The claim would “broadcast to Colored Americans everywhere,” according to California Realty Board attorney Hugh McBeth, “the opportunities, the welcome, the hope . . . which free California, its hills and valleys . . . and always sunshine offer to the American Negro.”23

Black Home Ownership Rates in Selected Cities

Sources: U.S. Bureau of the Census, Negro Population, 1790–1915 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1918), 471–501; Fifteenth Census of the United States: 1930. Population, vol 6, Families, 156–57, 194, 1098, 1270, 1402; Sixteenth Census of the United States: 1940, Housing, vol. 2, General Characteristics, part 2, 214, 327; part 4, 809; part 5, 274, 731. No figures were available for 1920.

Some black Angelenos gravitated to the independent community of Watts, seven miles southeast of downtown Los Angeles. Established in 1903, the town soon became attractive to white working-class families, who were drawn to its low rents and housing prices. However, Watts was unique among Los Angeles suburbs; from its founding black, Latino, and white migrants purchased houses and small farms. By 1920, 14 percent of Watts was African American, the highest percentage in any California community. Arna Bontemps, whose family arrived in 1906 from Alexandria, Louisiana, recalled the integrated setting that greeted early black migrants. “We moved into a house in a neighborhood where we were the only colored family. The people next door and up and down the block were friendly and talkative, the weather was perfect . . . and my mother seemed to float about on the clean air.” Bontemps’s grandparents bought several acres of farmland north of Watts and built a house, a summer house, and a barn. One 1913 newspaper advertisement offered houses for two hundred to five hundred dollars in cash or for ten dollars down and five dollars per month. By the 1920s Watts was an attractive, increasingly African American suburb whose reputation had reached the East. When the leading black Los Angeles realtor Sidney P. Dones relocated in this southern suburb in 1923, the Pittsburgh Courier announced, “Watts . . . is the coming Negro town of California.” The African American population of the community continued to grow after the town was annexed to Los Angeles in 1926, and by World War II it had become mostly African American. Both before and after annexation Watts remained, according to Lawrence B. de Graaf, “a lonely island in an otherwise white southeast Los Angeles.”24

Although some suburban home opportunities existed in Watts, Pasadena, Santa Monica, and Sierra Madre, most blacks resided in the Central Avenue district. African American Angelenos, like their counterparts across urban American, faced restrictive covenants that ensured residential segregation. Such covenants prohibited blacks, Asians, Native Americans, Latinos, and on occasion Jews from occupying certain neighborhoods. One Los Angeles resident in 1917 described these agreements as “invisible walls of steel. The whites surrounded us and made it impossible for us to go beyond these walls.” A 1927 covenant covered the residential area between the University of Southern California and the suburb of Inglewood, placing it off limits for people of color for ninety-nine years with the words “no part of any of the . . . lots and parcels . . . shall be sold or rented to any person other than those of the White or Caucasian race.” In order to ensure convenient domestic help, the covenant exempted “domestic servants, chauffeurs, or gardeners [who live] where their employer resides.” The California Supreme Court in 1928 upheld such agreements and ruled that even when blacks lived in neighborhoods before the restrictions were established, they must vacate properties under covenants. An occasional challenge succeeded, as in 1917, when Homer Garrett, a black policeman, appealed an order to remove him from a recently purchased house. The court, however, did not declare such agreements illegal. The most celebrated case of residential exclusion involved the family of realtor Booker T. Washington, Jr., who in the 1920s retained their home in the San Gabriel Valley.25

Restrictive covenants emerged in other western cities. Covenants created African American communities on Omaha’s North Side and in the industrial suburb of South Omaha. By 1940 Houston covenants (reinforced by a state law enacted in 1927) produced several all-black enclaves throughout the city, “like islands set apart,” according to urban historian Blaine Brownell. The 1942 WPA Guide to Dallas claimed that Oak Cliff, Deep Ellum, and other segregated communities that housed the city’s forty-three thousand African Americans “grew through the natural tendency of these people to live among their kind.” The evidence points to a pattern of segregation punctuated by violence against those who sought to live elsewhere. The Dallas Express reported a dozen bombings in 1940 against blacks who moved into all-white neighborhoods. Such violence prompted Mayor Woodall Rogers to write letters advising black residents not to relocate in white residential areas and to white homeowners urging them not to sell to African Americans. Ultimately the city bought property in “sensitive areas” to prevent residential integration.26

Restrictive covenants enforced residential segregation in Denver, as Claude DePriest, a black fireman, discovered when he attempted in 1920 to buy a house just beyond Five Points, the city’s black district. The Clayton Improvement Association warned him that “if you continue to reside at your present address, you do so at your own peril.” Soon afterward 250 whites demonstrated in front of the DePriest home. The harassed family moved. A year later the home of postal worker Walter R. Chapman was bombed to protest his arrival in a previously all-white neighborhood. When restrictive covenants were challenged in Oklahoma City in 1933, the state’s governor, Alfalfa Bill Murray, segregated the city by executive order, declaring, “I don’t have the law to do this, but I have the power.27

Virtually all Phoenix African Americans were restricted to the southwestern section of the city, a “cesspool of poverty and disease . . . permeated with the odors of a fertilizer plant, iron foundry, a thousand open privies, and the city sewage disposal plant.” Most black Phoenicians lived in shacks where “babies were born without medical care,” and “often died because of the extreme temperatures (up to 118 degrees) in the summer or froze to death in the winter.” San Francisco blacks avoided such squalor, but they nonetheless faced widespread restrictive covenants which prompted the San Francisco Spokesman to declare in 1927: Residential Segregation is as real in California as in Mississippi. A mob is unnecessary. All that’s needed is a neighbor [hood] meeting and agreement in writing not to rent, lease, or sell to blacks, and the Courts will do the rest.28 The campaign against residential segregation was to consume much of the time, energy, and resources of western black urbanites through the World War II period.

African Americans who migrated from Texas and Oklahoma to the West Coast thought they would encounter vastly different racial standards. Yet no region of the United States had completely avoided the burden of race. Houston, Dallas, or Oklahoma City blacks encountered segregation and discrimination via city ordinance or state law. Their counterparts in Los Angeles, Omaha, Denver, Seattle, and Phoenix were limited by private agreements. Segregated movie theaters and swimming pools were as common in Denver and Los Angeles as in Oklahoma City or Dallas. Most western blacks faced de facto public school segregation, but in Texas, Oklahoma, and Arizona the separation was de jure. Separate colleges were mandated in Texas and Oklahoma, but African Americans in public institutions throughout the west faced varying degrees of discrimination. Between 1913 and 1950 African American athletes in the Big Six Conference schools, such as the University of Kansas and the University of Nebraska, were banned from intervarsity competition because of the objections of the University of Missouri and the University of Oklahoma.29

Yet racial discrimination in the West was inconsistent. Most Portland and Seattle African Americans in 1920s and 1930s listed employment bias as their most serious challenge. Blacks in Phoenix worried about job discrimination and segregated schools. Houston and Dallas blacks noted similar limitations in 1928, but they also faced voting restrictions and segregated public accommodations. Houston’s segregation received national attention in 1928, when white Texas Democrats, hosting their party’s national convention, separated black delegates and spectators by a chicken wire fence. In Dallas as late as 1936 only twenty-seven of the city’s four thousand acres of parkland were open to African Americans. Moreover, although lynching of African Americans was not unknown in California, Kansas, Nebraska, North Dakota, and Oregon during this period, western blacks outside Texas and Oklahoma noted the absence of white mob violence used to intimidate blacks into accepting second-class citizenship. As one black Phoenix resident remarked in 1916 after living in Georgia, “At least they don’t lynch you here, like they did back there.”30

While grievances differed, responses were strikingly uniform. Community after community organized branches of the NAACP. Founded in New York City in 1910, the association arrived in the West in 1912, when Houston blacks organized a branch. By 1919 eleven branches existed in Texas. The largest was the twelve-hundred-member San Antonio branch. Oklahoma City and Seattle formed branches in 1913, with Denver, Portland, Albuquerque, and Omaha creating others the following year. In 1915 a Topeka branch was organized with Kansas Governor Arthur Capper a founding member. By 1919 branches had been established in Salt Lake City and Boise. Arizona was a particular area of early NAACP activity. Phoenix had the state’s first branch, but by 1922 statewide membership exceeded one thousand blacks and whites operating in Tucson, Flagstaff, Bisbee, and Yuma.31

The Los Angeles and northern California branches of the NAACP soon became the largest in the West. Los Angeles’s chapter was inspired by Du Bois’s 1913 visit, and a letter from E. Burton Ceruti (who less than six years later became the first westerner to sit on the association’s national board) to the national NAACP described housing restrictions and Jim Crow practices in southern California; “Problems and grievances arise constantly demanding attention. . . . We feel . . . the necessity of an organization such as yours. . . . Please advise.” Before the end of the year the NAACP branch was under way in Los Angeles.32

The northern California NAACP also began with Du Bois’s 1913 tour. The Crisis editor noted rigid patterns of segregation were absent in San Francisco. But he concluded, “The opportunity of the San Francisco Negro is very difficult; but he knows this and he is beginning to ask why.” When Oakland and San Francisco blacks petitioned for chapters in 1915, the national NAACP office urged them to combine their efforts into a Northern California branch headquartered in Oakland. Within two years of its founding the branch had 1,000 members.33

NAACP branches in the West, like the national organization, focused their initial efforts on D. W. Griffith’s film The Birth of a Nation, Hollywood’s first “epic” motion picture. The twenty-five million people who viewed The Birth of a Nation within one year of its 1915 release saw the first film to utilize a complex story line, a variety of Southern California locations, the pan shot, artificial lighting, night photography, and split screens. Griffith’s epic also employed far more black “extras” than any previous film, as hundreds of California African Americans portrayed soldiers, townspeople, and, of course, slaves. But the brief employment opportunities for African Americans in The Birth of a Nation could not compensate for its racist message of black incompetence and villainy during Reconstruction. That message generated the most extensive organized protest ever conducted against a feature film. The protest campaign was orchestrated by the NAACP national office, but local branches in such western cities as Seattle, Portland, Denver, Dallas, Wichita, and Topeka took independent action. The California branches led the way.34

The newly formed Northern California NAACP immediately sought to block showing of the film. Appealing to the San Francisco Board of Supervisors, it argued that the film was a “malicious misrepresentation of colored people, which create [d] enmity and hatred . . . disorder and race riots.” It appealed directly to Oakland Mayor Frank K. Mott, San Francisco Mayor James Rolph, and Governor Hiram Johnson. Of the three, only Rolph appeared sympathetic. At his urging the San Francisco Moving Picture Censor Board reviewed the film and advised the removal of certain racially inflammatory scenes involving physical contact between white women and black men “to make the picture less offensive to all sides.” NAACP leaders had hoped to prevent the film’s showing. They settled for this limited censorship. The film continued to play in Bay Area theaters until 1921.35

The Los Angeles NAACP’s protest began, and ended, earlier than the Bay Area effort. In February 1915, just days before the film’s New York premiere, black Angelenos attacked Griffith’s epic. The NAACP attempted unsuccessfully to get Los Angeles city officials to block its showing while the California Eagle kept up a barrage of attacks on both the film and the theaters that presented it. Moreover, the NAACP praised San Francisco city leaders for exhibiting more concern than Southern Californians over the movie’s potential impact on local race relations. Yet by March it was clear that the local efforts would fail. NAACP board member Arthur B. Spingarn admitted the film was a “masterpiece” and, “from an artistic point of view, the finest thing of its kind I have ever witnessed.”36

Spingarn’s comments exposed a dilemma posed by The Birth of a Nation. Clearly the film harmed race relations. Yet many liberals, normally committed to civil rights issues, thought the NAACP’s calls for banning the film unacceptable censorship. Thus, even as the campaign provided a crucial impetus to the fledgling association, the protest isolated the organization from potential allies. W. E. B. Du Bois reflected as much in a Crisis commentary, quoting at length from a white North Carolina newspaper that argued Griffith was a “mighty genius” against whom protest was pointless. Du Bois endorsed the paper’s view, urging African Americans to forget “the cruel slander upon a weak and helpless race” and instead create their own aesthetic tradition.37

Individual NAACP branches responded to other issues. In 1915 Oklahoma City’s NAACP, led by newspaper editor Roscoe Dungee, provided crucial assistance in Guinn v. United States, the national organization’s challenge to Oklahoma’s grandfather clause. The San Francisco branch (San Francisco seceded from the Northern California branch in 1923) investigated complaints of police brutality and public accommodations discrimination. It also raised money for the Scottsboro Defense Committee and brought suit against a segregated movie theater in Fresno. Both the San Francisco and Oakland branches fought the local Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), which one Northern California NAACP official in 1922 claimed “had much to do with retarding our progress.”38

The Texas branches’ legal campaign over black participation in the state Democratic primary was the longest effort of any NAACP chapters during the interwar period. Texas, which levied a poll tax, never barred African Americans from voting in general elections, but most black voters were effectively disfranchised because they were denied access to the Democratic primary in a one-party state. In January 1921 the Houston City Democratic Executive Committee passed a resolution expressly prohibiting blacks from voting in the coming primary election. In response Charles Norvell Love, editor of the Texas Freedman, filed suit against the Harris County Democratic party.39

This opening salvo in the legal war between black Texans and leaders of the state Democratic party led to four U.S. Supreme Court decisions between 1927 and 1944. Shortly after Love lost his lawsuit, the 1923 Texas legislature enacted the Terrell Law, which expressly said: “In no event shall a Negro be eligible to participate in a Democratic primary election . . . in . . . Texas.” The law prompted another suit by El Paso dentist Lawrence A. Nixon, who quickly emerged as the symbol of the Texas suffrage campaign.40

Lawrence Aaron Nixon moved to El Paso from Marshall, Texas, in 1910 and five years later helped found the city’s NAACP branch. In 1924 NAACP Field Secretary William Pickens visited El Paso and announced that the NAACP intended to test the constitutionality of the Terell Law. Pickens asked for volunteers to file a lawsuit. “We are looking for someone who is not afraid,” he said, and Nixon stepped forward. On Saturday, July 26, Nixon presented himself to local election officials. “The [election] judges were friends of mine,” he recalled. “They inquired about my health, and when I presented my poll-tax receipt, one of them said, ‘Dr. Nixon, you know we can’t let you vote.’ ” “I know you can’t,” Nixon responded and then added, “but I’ve got to try.”41

NAACP attorneys from the local branch and the national office won Nixon v. Herndon before the U.S. Supreme Court in 1927. Subsequently the Texas legislature modified the exclusion statute to satisfy the Court, but in 1928, having been denied a Democratic primary ballot, Nixon again filed suit. The High Court in Nixon v. Condon (1932) again ruled in favor of the plaintiff, concluding that the state Democratic party convention rather than the legislature had the power to bar blacks from voting in the primary.42

For twelve years the Texas Democratic party tried to limit the impact of the Supreme Court rulings while African Americans fought to widen their scope. Local leaders, such as James M. Nabrit and Carter W. Wesley of Houston, C. A. Booker of San Antonio, and Richard D. Evans of Waco, all pursued various legal strategies against county Democratic organizations. El Paso party officials allowed only two black city residents, Nixon and a pharmacist, M. C. Donnell, to vote in the July 1934 primary, providing them with ballots marked “colored.” Black Texas voters received an additional setback the following year, when the U.S. Supreme Court in Grovey v. Townsend upheld the Democratic party’s right to limit its membership.43

In 1941 the NAACP launched a final assault. Pressured by the Houston branch and working under Thurgood Marshall’s leadership the NAACP found a test case. Harris County election Judge S. E. Allwright denied a primary ballot to Dr. Lonnie Smith, a Houston physician. In Smith v. Allwright the U.S. Supreme Court voted eight to one in January 1944 to declare the all-white primary unconstitutional. The NAACP had won the greatest legal victory of its thirty-four-year history.44

The NAACP remained dominant in the West, but two other organizations, the National Urban League and the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), had moderate success organizing black westerners during this period. These organizations stood on either side of the NAACP. The National Urban League, founded in New York City in 1911, sought employment for urban blacks and helped rural migrants adjust to city life. The UNIA, formed by Marcus A. Garvey in 1914 in Kingston, Jamaica, and relocated two years later in Harlem, advanced three black nationalist aims: African independence, worldwide black political unity, and economic self-sufficiency.45

The National Urban League grew slowly in the West, adding affiliates in Omaha in 1928, Seattle and Los Angeles in 1930, and Lincoln, Nebraska, in 1931. Although the Urban League is often described as a conservative rival to the NAACP, in western cities their membership overlapped as middle-class blacks divided their activities into NAACP “protest” and Urban League “uplift.” In Seattle the league, under the leadership of Joseph S.Jackson, confronted social and economic problems, sponsoring community recreation and health programs and vocational training sessions. The Lincoln affiliate built a thirty-five-thousand-square-foot, sixteen-room community center that became the nucleus for the city’s African American activities for the next three decades. The league accumulated statistics on the education, health, and employment of African Americans in all the cities it served.46

The Universal Negro Improvement Association was the only organization to challenge NAACP leadership. The UNIA’s program proved popular among western African Americans skeptical of the NAACP’s integrationist thrust. By 1926 UNIA divisions operated in nine of the seventeen western states. Indeed the small size and isolation of African American western communities enhanced the UNIA’s appeal. Divisions, which required only seven members, sprang up in Mesa, Arizona; Colorado Springs, Colorado; Coffeyville, Kansas; Mill City, Texas; and Ogden, Utah, symbolizing a desire to interact with the larger black world. Emory Tolbert has used the term outpost Garveyism to describe the UNIA’s attraction in small black communities. In California, for example, the association functioned in Bakersfield, Durante, Fresno, Wasco, and Victorville before it reached Los Angeles or San Francisco. By 1926 it had divisions in Omaha, Denver, Dallas, Kansas City, Oklahoma City, Tulsa, Portland, San Francisco, San Diego, Phoenix, and Oakland.47

African American Los Angeles was the center of western Garveyism. Black Angelenos had long supported black nationalist activity centered on the efforts of John Wesley Coleman. From the time of his arrival in the city in 1887 from Austin, Texas, Coleman had been active in the People’s Independent Church and the Los Angeles Forum. In 1920 he founded the National Convention of Peoples of African Descent, an enigmatic organization that, with its parades, race unity rhetoric, and interest in Pan-Africanism, paralleled Garvey’s UNIA. As Coleman learned of the larger Garvey movement, he dissolved the convention and, along with the Reverend John Dawson Gordon and the editors of the California Eagle, Charlotta and Joseph Bass, founded Division 156 of the UNIA in 1920. A year later the division’s thousand members made it the largest UNIA branch west of Chicago. The first UNIA president was newspaper writer and former Tuskegee Institute employee Noah Thompson. Subsequent presidents included two women, Charlotta Bass and Rosa Jones. The full extent of UNIA influence could be gauged in 1922 during Garvey’s first Southern California visit. The welcoming parade down Central Avenue drew ten thousand spectators, almost half of the region’s black population. Seated next to Garvey in the automobile was Frederick Roberts, the state’s only black assemblyman. The parade ended at Trinity Auditorium, where the UNIA founder addressed a gathering of a thousand people following a welcoming speech by a representative of Mayor George Cryer.48

The UNIA did not survive the Depression. Yet during its heyday numerous working-class western black urbanites were drawn to its race consciousness. Seattle Garveyites Samuel and Maudie Warfield welcomed the opportunity to attend, with other Garveyites, the daylong Sunday UNIA meetings or to participate in the annual Memorial Day and Fourth of July parades of the paramilitary men’s unit, the African Legion, and the women’s auxiliary, the Black Cross Nurses. “They were trying to teach us about Africa,” recalled Juanita Warfield Proctor, “that we should know more about Africa. . . .” The UNIA’s focus in the West and throughout much of the black world was on political and economic empowerment, but to many Garveyism symbolized racial pride. Juanita Proctor explained Garvey’s influence on her father and by extension on her. “My father [told] us we should be proud of Africa. . . . He used to say, ‘Be proud of your race. . . .’ We were never ashamed to be called Black. . . . That’s why [now] I’m not ashamed of people calling me black . . . my parents taught me differently.”49

The economic and political nationalism embraced by many early-twentieth-century black westerners paralleled a western-based literary tradition. Sutton E. Griggs, a black Texan, wrote a series of novels between 1899 and 1906 urging African American political and economic autonomy. In Imperium in Imperio (1899), his most influential work, Griggs portrayed Texas as an all-black state, a refuge for African Americans fleeing southern political terror. In subsequent novels, such as Unfettered (1902) and Pointing the Way (1906), he criticized racial discrimination and proposed a national organization to defend black rights that anticipated the founding of the NAACP.50

Drusilla Dunjee Houston explored black life as a historian. Born in Harpers Ferry, Virginia, and the sister of Roscoe Dunjee, the civil rights activist and founder of the Oklahoma City Black Dispatch, Houston lived most of her life in Oklahoma and Arizona. She operated the McAlester Seminary, a private school for African American students in McAlester, Oklahoma. In 1926 she published The Wonderful Ethiopians of the Ancient Cushite Empire, the first of a projected series on African civilization. The Wonderful Ethiopians, which examined ancient Egypt and Ethiopia, was widely reviewed in most of the African American newspapers and journals of the day. Mary White Ovington of the NAACP criticized the book’s lack of footnotes and bibliography while acknowledging its “exciting influence” upon her perception of European history. Upon publication of her Astounding Last African Empire, Houston became the first African American woman to complete a multivolume history of blacks in antiquity. That she could accomplish such a feat in an intellectual milieu dominated by black men and far from the major eastern research sources prompted NAACP leader William Pickens to remark: “If her race were . . . economically able to buy her books, what an historic foundation she could lay for them. . . . Perhaps some day we will build her a statue, or name a university after her, when we have finished starving her to death. . . .”51

Langston Hughes, considered the greatest contributor to the Harlem Renaissance, also started in the West. Born in Joplin, Missouri, in 1902, Hughes spent his childhood years, from 1903 to 1915, in Lawrence and Topeka, Kansas. He was part of a prominent, if poor, family; his maternal grandfather, Charles Langston, led the post–Civil War black suffrage campaign in Kansas. Hughes’s early writing reflected this upbringing. His first novel, the semiautobiographical Not without Laughter (1930), describes a young man’s early years in a Kansas town. Many of Hughes’s poems and short stories evoke his images of the West. In “One Way Ticket” he suggests the region’s possibilities for “freedom.”

I pick up my life

And take it on the train

To Los Angeles, Bakersfield,

Seattle, Oakland, Salt Lake,

Any place that is

North and West52

Hughes’s Harlem Renaissance contemporary Wallace Thurman also drew inspiration from his native West. Thurman, who was born in Salt Lake City, spent time in Boise, Omaha, and Pasadena before settling in Los Angeles. While enrolled at the University of Southern California, he wrote poetry and briefly edited a literary magazine, the Outlet, which he hoped would encourage a West Coast renaissance similar to Harlem’s. While at the university, Thurman met another rising literary star, Arna Bontemps. By 1925, however, Thurman had abandoned his efforts to establish a western “New Negro” Movement and joined Bontemps and Hughes in Harlem. Thurman’s essays ranked him the major satirist of the Renaissance, but his novel The Blacker the Berry (1929) reflects the author’s western origins as it focuses on an African American heroine native to Boise who moves to Harlem.53

Hughes, Thurman, and Bontemps were the contemporaries or precursors of Ralph Ellison, Taylor Gordon, Melvin Tolson, Sr., J. Mason Brewer, and other African American writers who explored black life through the prism of their western experiences. Despite their efforts, a regional literary aesthetic did not emerge. The small African American population, its recent arrival in the region, its scant identification with the rural West, which was at that time the principal focus of regional writing, and the absence of regional outlets for black writers all weighed heavily against a western African American literary tradition. Only Los Angeles nurtured a fledgling western renaissance. Langston Hughes, Arna Bontemps, and other writers periodically visited this “ever enlarging artistic colony,” where Fay Jackson’s Flash Magazine (1928–29) supplanted Wallace Thurman’s short-lived Outlet as the second black literary journal in the West. Local artists and national writers mingled at the Twenty-eighth Street YMCA, near Central Avenue, where they read poetry and discussed their work. Los Angeles became the setting for Arna Bontemps’s Depression-era novel God Sends Sunday (1931), which focuses on the hope and despair southern migrants found on Central Avenue, the “Beale Street of the West.” Despite these efforts, black Los Angeles’s major literary contribution lay in the future.54

Western African American musicians fared better than writers. They thrived in Kansas City, Los Angeles, Seattle, Dallas, Oklahoma City, and Denver and in the process helped shape the evolving national jazz culture of the 1920s and 1930s. Urban jazz grew from a variety of musical traditions, including southern blues, ragtime, and boogie-woogie, the last originating in western mining and lumber camps. Encouraged by the proliferation of Prohibition-era nightclubs, cabarets, and speakeasies, hundreds of black bands crisscrossed the region, freely borrowing and changing musical styles. Many of these nightclubs and cabarets were in African American urban communities, but even when they were not, they offered jobs to black musicians, who provided a colorful alternative to vaudeville, the concert stage, and legitimate theater.55

Most music historians no longer describe jazz as originating in New Orleans and flowing up the Mississippi to Chicago and the rest of the nation. Black musicians played jazz or its precursor in various African American communities from San Francisco to New York before New Orleans musicians began to migrate north. As early as 1907 indigenous black San Francisco performers “improvised” their music. Denver musician George Morrison claims to have played jazz music in 1911 and appropriated the name for his newly formed band, George Morrison and his Jazz Orchestra. By 1913 the word jazz appeared not in New Orleans but in a San Francisco newspaper description of local African American artists. Four years later a Honolulu newspaper advertised visiting San Francisco musicians as the “So Different Jazz Band.”56

In the 1920s Kansas City emerged as a vital center of jazz. Black musicians from Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas, and Colorado made their way to Kansas City’s nearly five hundred nightclubs, taverns, cabarets, and honky-tonks to join local artists. This dynamic music scene rivaled Harlem and Chicago’s South Side. “Work was plentiful for musicians, though some of the employers were tough people. . . .” recalled jazz vocalist Mary Lou Williams. “I found Kansas City to be a heavenly city—music everywhere in the Negro section of town, and fifty or more cabarets rocking on Twelfth and Eighteenth Streets.”57

The southwestern origins of most of the jazz musicians who migrated to Kansas City generated the city’s distinct musical style, which historian Ross Russell describes as “grassroots . . . retaining its earthy, proletarian character . . .” because it drew inspiration from folk songs, ragtime, and blues. “Don’t let anyone tell you there’s a ‘Kansas City style’ ” wrote a Down Beat reporter in 1941. “It isn’t Kansas City—it’s Southwestern. The rhythm, and fast-moving riff figures, and emphasis on blues, are the product of musicians of the Southwest—and Kansas City is where they met and worked it out. . . .”58

The African American communities in Houston, Dallas, San Antonio, Fort Worth, El Paso, Oklahoma City, Denver, and Omaha provided the first audiences for little-known but ambitious jazz artists, eager to introduce their particular musical style to the wider world. Dallas’s Deep Ellum, for example, “swarmed with blues singers, boogie woogie pianists and small combos” that constantly formed and dissolved acts that played the clubs and bars of the city.59

Jazz bands also went on the road. The Oklahoma City—based Blue Devils’ circuit took them through Kansas, Nebraska, Missouri, Arkansas, Texas, Colorado, and New Mexico. Often bands traveled hundreds of miles between engagements with as many as ten performers crammed into a single automobile, one or two of them standing on the running board. “Maybe we’d go from [Omaha] to Sidney, Nebraska,” Walter Harrold recalled; “then we’d go from there to North Platte, we’d have an engagement the next night. . . . Then we had to go to Norton, Kansas, we had a four-day fair to play there.” The circuit Harrold described encompassed Nebraska, Colorado, Kansas, South Dakota, and Wyoming and could involve travel of fifty thousand miles a year.60

These “territorial bands” operating west of Kansas City fell into two broad categories. Some played in Texas and Oklahoma, where their audiences were African American patrons of cabarets, ballrooms, taverns, and saloons. Representative examples include the Troy Floyd Orchestra in San Antonio, the Blues Syncopaters of El Paso, Clarence Love’s Band in Tulsa, and Henry (“Buster”) Smith’s Blue Devils of Oklahoma City, which included at various times Lester Young, Count Basie, and vocalist Jimmy Rushing. Dallas contributed the Clouds of Joy and the Alphonso Trent Orchestra. Trent’s musicians played gold-plated instruments, made $150 a week, wore silk shirts and camel hair overcoats, and drove Cadillacs as they performed from New York’s Savoy Ballroom to roadhouses in Dead-wood, South Dakota. In 1925 the Trent band was the first black ensemble to play regularly at the Adolphus, a white Dallas hotel, and the first black group outside New York City to broadcast over radio.61

Other black jazz artists played for white audiences farther north and west. George Morrison, a classically trained musician who aspired to conduct a symphony orchestra, gave his name to the band he organized in Denver in 1911. The George Morrison Jazz Orchestra appeared regularly at Denver’s Albany Hotel and traveled a circuit that included Colorado, New Mexico, and Wyoming. The orchestra was the official band for the Cheyenne Frontier Days rodeo, beginning in 1912, and was popular on the southwestern college circuit. Hattie McDaniel, who later won an Oscar for her performance in Gone with the Wind, was the band’s vocalist. Albuquerque-born John Lewis, who eventually became the pianist with the Modern Jazz Quartet, recalled the band’s visit to New Mexico as his introduction to African American dance music. Omaha, in the shadow of Kansas City, developed a jazz tradition with the World War I black migration and by the 1920s had produced a number of musicians, including Fletcher Henderson, Lloyd Hunter, and vocalist Victoria Spivey. Salina, Kansas, was the home to Art Bronson’s Bostonians, the state’s leading band in the 1920s. In 1925 Bronson hired sixteen-year-old saxophonist Lester Young, who had previously worked with his father’s band on the medicine show and minstrel circuit from Arizona to the Dakotas. Young later recalled that playing “music was better than blacksmithing,” a reminder of limited opportunities even for gifted musicians.62

The West Coast’s jazz culture rivaled the Southwest. Los Angeles, Portland, Seattle, San Francisco, and Oakland all drew on a complex mixture of local and imported influences. Many New Orleans jazz musicians migrated to the West Coast around World War I, enhancing the protojazz styles that evolved earlier with local artists. New Orleans performers Wade Whaley, Will Johnson, and Edward (“Kid”) Ory helped shift the center of West Coast jazz from San Francisco to Los Angeles by 1920. The “Creoles” remained important through the mid-1920s, but growing numbers of Texans, Oklahomans, and midwesterners, including Lionel Hampton and Charlie Lawrence, challenged their dominance in Los Angeles.63

This new generation of Los Angeles musicians produced a sophisticated style featuring danceable arrangements that eventually inspired the swing era of the 1940s but that, unlike the Kansas City–southwestern style, did not emphasize blues. Moreover, the Los Angeles artists had more diverse performance opportunities than their counterparts to the east. Central Avenue had become by 1925 the vital pulse of West Coast jazz with its “hot-colored” nightclubs: the Kentucky Club, the Club Alabam (known in the 1920s as the Apex), the Savoy. The Cotton Club in Culver City attracted white and black celebrities: Mae West, Orson Welles, Joe Louis, and William Randolph Hearst. Radio also featured black artists. After the advent of sound films some bands played “mood music” for movie studios or appeared in movies directed toward black audiences. As the studios recognized the market for these black-oriented films, such performers as Louis Armstrong, Lena Horne, Bill (“Bojangles”) Robinson, and Duke Ellington supplemented their incomes by arranging local club dates, while aspiring actresses, such as Carolynne Snowden and Mildred Washington, sang and danced in the clubs “between roles.”64

West Coast jazz, however, was not synonymous with Los Angeles. San Diego’s Creole Palace nightclub had become by the 1930s the most famous West Coast cabaret outside Los Angeles. Built along with the Douglas Hotel in 1924 by black entrepreneurs Robert Lowe and George Ramsey, the Palace in the 1930s became well known in the national black community of entertainers. It employed black and Latino band members, show girls, waiters, cooks, and busboys and attracted Duke Ellington, Lionel Hampton, and Joe Louis as well as local black, white, and Latino patrons.65

Like their southwestern counterparts, these musicians traveled a circuit that included Honolulu, the major West Coast ports, and southwestern cities, such as Phoenix and Albuquerque, in the 1920s but that had expanded by the 1930s to embrace Yokohama, Shanghai, Hong Kong, and Manila. The Seattle-based Earl Whaley Band, for example, played in Shanghai clubs between 1934 and 1937, and most of the band members were imprisoned by the Japanese Army during its occupation of the city.66

Most black West Coast musicians worked closer to home. Seattle’s Jackson Street had the Alhambra, the Ubangi, and the Black and Tan Club. Doubling as restaurants in the day and early-evening hours, these clubs flouted law and custom by allowing gambling, after-hours drinking, and interracial mingling. As Robert Wright, the nephew of a leading black nightclub owner, recalled, “In 1935 and 1936 you could see as many white people on 12th and Jackson at midnight, as you’d see on 3rd and Union in midday.” Interracial mingling was not confined to whites and blacks. Up and down the coast black musicians played in Asian and Latino clubs. Baton Rouge–born Joe Darensbourg performed in Mexican and Filipino cabarets in Los Angeles and Asian clubs in Seattle. Seattle’s jazz scene was particularly noted for the extensive camaraderie between Asian Americans and African Americans. The Chinese Gardens and the Hong Kong Chinese Society Club were leading venues for local jazz and regularly hired black musicians. African American and Filipino bands alternated in the dance halls of Little Manila, while struggling black musicians lived at the Tokiwa Hotel and ate at local Japanese restaurants. As Julian Henson recalled, “Most of the musicians who lived at the Tokiwa owed [the owners] money, but they wouldn’t put you out.” Added Marshal Royal: “They were a different type of people up in Seattle. . . . They were nice, they were cordial. I’m not just speaking of black people, I’m talking about the Chinese guys. . . . They were our buddies.”67

Seattle’s jazz scene was unique in another respect. Female bandleaders were among the first jazz artists in the city. Indeed Lillian Smith’s Jazz Band, which played at a Seattle NAACP benefit fund raiser on July 14, 1919, gave the first documented jazz performance by local musicians in the city’s history. In the mid-1920s the Freda Shaw Band (which often played on the Seattle-based cruise ship SS H. F. Alexander), the Evelyn Bundy Band, and the Edythe Turnham Orchestra were considered three of the city’s leading jazz acts. Other black women, such as Lillian Goode, Zelma Winslow, and Evelyn Williamson, became performers in local club acts.68

The rise of an active jazz network in western cities symbolized white recognition of black influence on popular entertainment. But it also indicated black western urbanites’ identification with national cultural patterns. This process affected all westerners; urbanization rapidly homogenized the entire nation. But the African American population was urbanizing faster than most other regional ethnic and racial groups. These western urban communities defined the political issues, responded to the economic challenges, and created the social and cultural milieu that greeted much larger numbers of black migrants by World War II.