COUNTDOWN: 282 DAYS

February 1, 1960

Greensboro, North Carolina

It was a long mile-and-a-half walk in their Sunday shoes, but the weather was kind to the four freshmen from the historically Black Agricultural and Technical College of North Carolina. Franklin McCain and his dorm mates stopped in front of the F. W. Woolworth store in downtown Greensboro, North Carolina.

It was a busy place, part of a national chain of five-and-dime discount stores. Black people could shop there, but they had to stick to a set of store policies designed to keep them in their place. McCain and his friends traded glances and nods, then stepped past the plate-glass double doors.

The Greensboro Woolworth store was one of the few places downtown where shoppers could have a seat at a lunch counter for a quick meal. At least white shoppers could. Woolworth’s lunch counter had a “whites only” policy, just like many other cafés, stores, and retail outlets across the American South.

That’s why McCain, Ezell Blair Jr., Joseph McNeil, and David Richmond walked into town that day. They came to create a stir.

McCain wondered if they’d be arrested or beaten. Or something even worse. In a place like Greensboro, anything could happen. Greensboro was the second-biggest city in North Carolina, and white people ruled the town. Jim Crow, a system of laws that legalized racial segregation, codified their racial prejudices.

In 1960, America moved slowly toward racial equality partly because of detours placed along the road to civil rights by southern governors. Many southern states still refused to abide by the 1954 U.S. Supreme Court ruling ending racial segregation in public schools. The state of Arkansas had tried to defy federal court orders in 1957 to integrate. So, President Eisenhower sent U.S. troops to protect Black students trying to attend class at Little Rock Central High School.

Vice President Nixon was a supporter of civil rights. He had worked on legislation to prevent racial discrimination in federal contracts. And he was instrumental in pushing Congress to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1957 through Congress. The law allowed federal prosecutors to seek injunctions if anyone tried to stop minorities from voting.

Nixon had met repeatedly with civil rights leaders and promoted his administration’s record. He knew the Black vote would be important in November.

The vice president had asked prominent Black leaders for advice on how to improve race relations, forming ties with the Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. and Jackie Robinson, who had broken baseball’s color barrier in 1947. Meanwhile, Jack Kennedy had been silent about segregation. He had voted for a watered-down version of the Civil Rights Act and refused to condemn southern governors who opposed integration.

But even with Nixon’s support and some progress, Black people in the South were not allowed to use the same bathrooms, water fountains, public parks, beaches, or swimming pools as whites. They were only allowed to sit in designated sections of movie theaters. Some restaurants were off-limits, or relegated Black customers to stand-up snack bars or take-out windows.

Franklin McCain was tired of this second-class treatment. Today he was going to fight back, but in a peaceful, nonviolent way.

McCain and his friends had devised their plan the previous night during one of their many “rap sessions”—late-night discussions when they’d talk about current issues and racial inequality. Sometimes they went on until dawn.

The four eighteen-year-olds had met in the fall of 1959, when they moved into the same dormitory. They discovered they could be open and honest with one another about issues that were usually hushed up and kept quiet back home. They didn’t hold anything back.

It was during their last rap session that McNeil had expressed his frustration with the slow pace of desegregation. It seemed like everybody talked about ending Jim Crow, but nobody stepped up and did anything to challenge it.

“It’s time to take some action now,” McNeil said.

The others nodded in agreement. But what kind of action?

They modeled themselves after Reverend King and his nonviolent protests. King had organized a boycott of the Montgomery, Alabama, bus system after a Black woman named Rosa Parks was arrested on December 1, 1955, for refusing to give up her seat to a white passenger. The tactic proved to be a powerful economic tool. More than 75 percent of Montgomery’s bus ridership was Black—and an overwhelming majority supported the boycott.

Black men and women walked, carpooled, or found other ways to get around instead of using the municipal bus system. The protests ended after the U.S. Supreme Court prohibited segregated seating on public transit. The boycott lasted 381 days—and provided civil rights activists with a blueprint for social action.

If they could do it in Montgomery, they could do it in Greensboro, McCain said. So that night, McCain, McNeil, Blair, and Richmond challenged one another to do something that would change the nation.

The lunch counter was Joseph McNeil’s idea. He’d grown up in Wilmington, North Carolina, but his family had moved to New York City. On his bus trip back to Greensboro after Christmas break, McNeil arrived hungry—and once over the Mason-Dixon Line, a Black man couldn’t buy a meal in a southern bus depot.

He suggested to his friends that they should try to order food at the Woolworth lunch counter. If they weren’t served, they’d stay. Woolworth was the perfect target. It was considered one of the company’s flagship stores. With marble stairs and 25,000 square feet of retail space, the company encouraged Black and white customers to spend money in their store. But McNeil knew Black people were treated as unwelcome guests. He was done with eating his sandwiches standing up in a far corner of the store.

The young men stayed up for hours, meticulously planning the details.

Franklin McCain had grown up following his parents’ and grandparents’ advice: Get a good education, do good, and fight for your rights. Sometimes that was easier said than done, but Franklin was ready to change the system.

The following day, the teens went to class, regrouped, reviewed their plan, and left campus on foot. It was sunny, with temperatures in the mid-50s—a perfect day for the hike. Along the way, the young men stopped at a pay phone to let some friends know what they were about to do, just in case something bad happened.

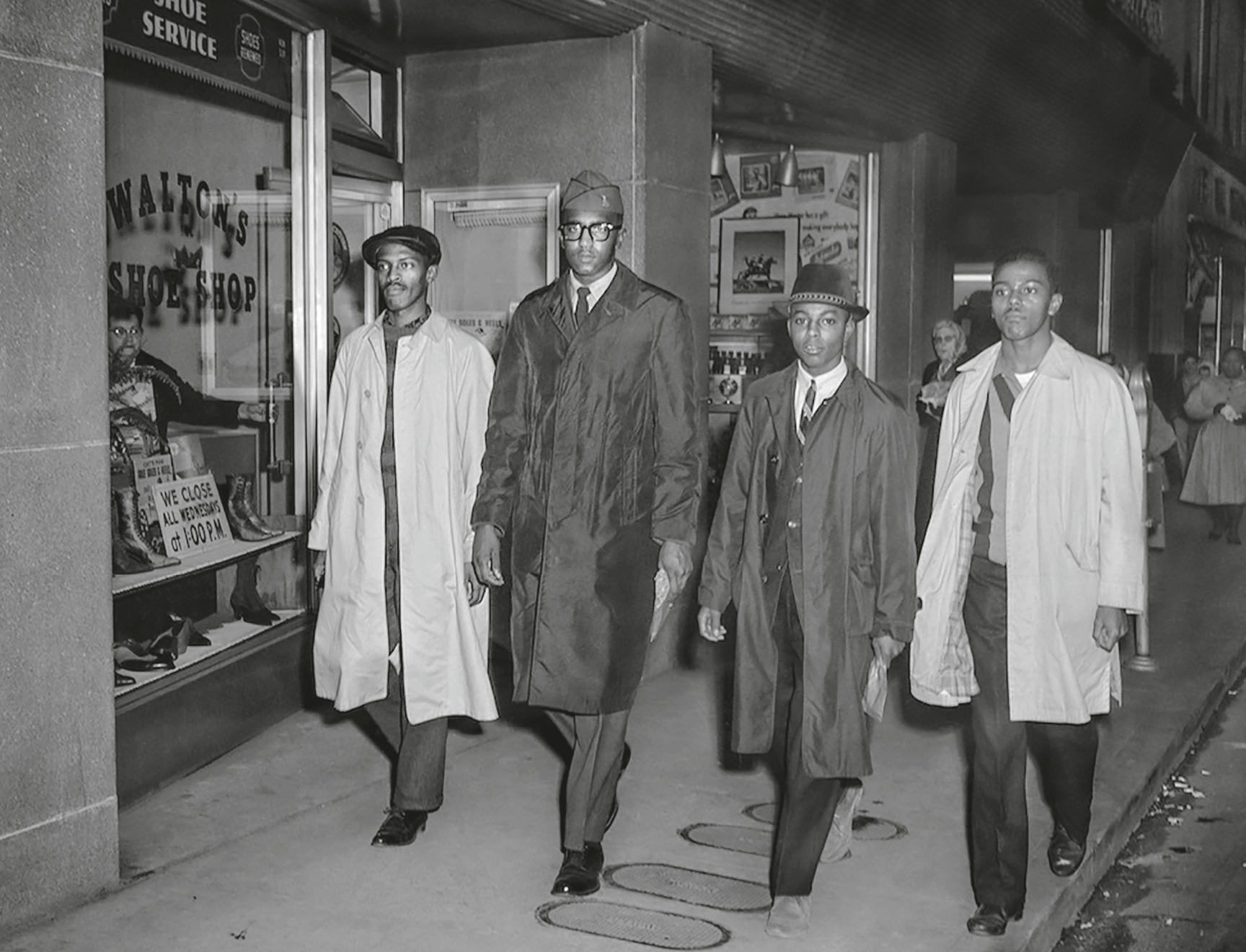

The Greensboro Four (L to R: David Richmond, Franklin McCain, Ezell Blair Jr., and Joseph McNeil), February 1, 1960

(Photo by Jack Moebes / Jack Moebes Photo Archive / www.jackmoebes.com)

McCain wore his Air Force Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC) uniform. The others wore their Sunday-best coats, hats, collared shirts, and ties.

They walked together into the store and spread out to make some purchases.

McCain bought a tube of toothpaste, paper, and colored pencils for a homework assignment. His friends made other small purchases. They made sure to get receipts, just to show that Woolworth took their money at one turn but refused to serve them at another.

They stepped over to the lunch counter. McCain was craving a cheeseburger and fries and wanted to chase it down with a cherry soda and maybe a banana split.

It was a big place. Sixty-six aqua and orange pedestal stools with chrome-plated backrests stood along an L-shaped Formica lunch counter. The students moved in silence. There weren’t four seats together, so they split up. McCain sat next to McNeil on the far end, Blair and Richmond nearer the entrance.

As they settled into their chairs, they knew they’d crossed an invisible line. Heads turned. The cafeteria went quiet. The clock above the counter showed some time around 4:45 p.m. The store closed at 5:30.

The waitress was white. McCain politely asked her for a coffee. McNeil did the same.

“I’m sorry. We don’t serve colored here,” she said, directing them to the area where they would be served.

McCain was angry. He knew the lunch counter was segregated, but hearing those words cut him like a knife. McCain was a big, quiet, gentle young man, a chemistry and biology major in the ROTC. He believed in America. He believed in his rights.

McCain knew he had to maintain his composure. But that didn’t mean he couldn’t challenge her.

“You just served me at a counter two feet away. Why is it that you serve me at one counter and deny me at another? Why not stop serving me at all counters?” McCain asked.

The waitress didn’t know how to respond. She walked away from McCain and his friends and simply focused on the white customers. Then she vanished into the kitchen. She’d gone to find the manager.

McCain’s eyes met his friends’ down the counter. They stayed put. They were going to sit there until they were served or arrested, or until the store closed. This was only the beginning.

Tension was building inside the Woolworth. McCain felt his heart pounding, but he didn’t feel afraid. He thought of the many times he’d been called the N-word, how freely whites called him “boy,” how many times he’d feared for his life.

He thought of the stories of Blacks who’d stepped out of line and been lynched, the horrible images of Emmett Till in Jet, a magazine that provided a voice for the Black community.

A white woman in August 1955 had accused Till, a Chicago teenager visiting relatives in Money, Mississippi, of whistling at her in a store. A few days later, the woman’s husband and his half brother kidnapped and tortured Till, dumping his lifeless body in the Tallahatchie River. The men were caught, but an all-white jury quickly acquitted them.

When Till’s mother, Mamie, brought his body home to Chicago, she wanted people to see what happened to her son. She told the funeral director, “Let the people see what I’ve seen.” Tens of thousands filed past Till’s open casket. A photographer took pictures of the teenager’s mutilated corpse. Nearly five years later, those images were seared into McCain’s memory.

That’s what happened to young Black men who defied orders in the South. Sometimes McCain felt so dispirited he didn’t want to live anymore.

But something strange happened at the lunch counter. Yes, McCain felt scared, but he felt transformed, too. He’d stepped up. He was doing right. He had “made a down payment on my manhood” by this simple act of courage. If he went to jail—or if this was the last day of his life—so what? What good was living if you couldn’t live free?

McCain realized at that moment that he and his friends were parked in their seats like “a Mack truck.” No one was going to move them.

The waitress returned with store manager Clarence Harris. He asked them to leave, but the students refused. A police officer arrived moments later, conferred with Harris, then headed for the young men. McCain’s heart hammered when the policeman pulled his baton from its holster. “This is it,” McCain said to himself.

The officer paced behind McCain and his friends—back and forth, back and forth—slapping the baton into his palm. He didn’t say a word.

It was unsettling, but as long as they didn’t cause trouble, as long as they stayed quiet, what could he do? There was no reason to take them in. After all, what did they do wrong?

The officer left the store. Some of the white patrons tossed out racial slurs as they paid and left. But most of the customers just stared.

All but one. An elderly white woman who’d been sitting at the counter got up and headed for McCain, the only young man in uniform. He braced himself for the worst.

The woman sat down next to him and looked into his face. “I’m disappointed in you,” she said, loud enough for his friends to hear.

McCain sighed. “Ma’am, why are you disappointed in us for asking to be served like everyone else?”

She paused and replied, “I’m disappointed at you boys because it took you so long to do this.”

With that, she got up and left the store. For McCain and the others, it was vindication. This was the time to fight to end another vestige of the old South. It was the time to push for change—no matter how dangerous. No matter the personal risk.

At 5:30 p.m. the manager scurried back to the lunch counter. The store was closing early, he announced. Everyone, including the students, had to leave. Right now.

McCain gathered his things and walked to the front door with his friends. They realized what they had done. They had simply taken a seat at the counter. They had asked to be served. They had sat there peacefully and quietly. And by doing just that, they had paralyzed the store, its staff, its patrons, and the police, for an entire hour that Monday afternoon.

None of them expected to walk freely out of the Woolworth that day. It seemed much more likely they’d be arrested or injured or even killed. And while they weren’t served any food, they knew this was only the first step in a long journey.

Outside, McCain and his friends agreed to return to the lunch counter with even more students. They’d keep coming back until Woolworth and other restaurants ended their discrimination.

The young men headed back to campus in the gathering dark. They had homework to do. And calls to make. Many calls.