COUNTDOWN: 267 DAYS

February 16, 1960

Detroit, Michigan

Anyone else but Richard Nixon would have been elated. Public opinion polls showed that if the election were held then, Nixon would win big—no matter who he faced in November.

But Nixon didn’t put much stock in polls this early in the election cycle. He hoped his strong numbers meant his strategy, as 1960 campaign reporter and historian Theodore White put it, of “choosing to adopt the nonpolitical posture of statesman” was working. Maybe trips like today’s stop in Detroit were paying dividends.

Nixon had just whisked through a grueling twelve-hour day of speeches touting the Eisenhower administration’s accomplishments. He had even called for an end to racial discrimination, calling it a moral issue that had sullied America’s international reputation.

The one thing Nixon scarcely mentioned was his own candidacy for the Republican nomination. And he didn’t attack any of his potential Democratic opponents, either.

Democrats were lobbing more political and personal attacks his way. News columnists were dredging up his past controversies, trying to portray him in the worst possible light.

How long could he stay above the political fray? It wasn’t really in his nature. But so far, he had.

It was a precarious political strategy, yet one that Nixon handled adroitly in the Motor City. During a noontime speech at the Detroit Economic Club, Nixon told the nation’s automotive moguls that Eisenhower had kept the nation safe and strong.

“We can and will do whatever is necessary to be sure we have enough [weapons] to destroy (Soviet) war making capability,” Nixon said.

And just like Ike, Nixon called for less government control of the economy, saying Americans could place their faith “in the principle that the wellspring of true economic growth is the creative enterprise of free people, free business and free labor.”

Nixon looked trim and energetic—he’d lost as much as fifteen pounds. He stood upright, spoke in well-rehearsed truisms. His cool demeanor was a product of long study and planning.

If Nixon had to battle New York governor Nelson Rockefeller for the Republican Party’s favor, his advisers predicted GOP regulars would strongly back Nixon. He’d accrued plenty of political equity over his eight years as vice president. He’d campaigned and raised money tirelessly for GOP candidates all over America.

Nixon’s dignified statesman image was a vital asset and should be preserved as long as possible, his campaign team advised. He should stick to places and issues where his exposure was chiefly nonpolitical.

So, Nixon cruised through Detroit, looking and sounding presidential. His only candidate moment was when he fielded questions from the media. Cool and unhesitating, Nixon answered every question with easy assurance.

When asked if he foresaw a mudslinging election campaign, he promised he wouldn’t indulge in such tactics. If Kennedy was the Democratic candidate, he promised he wouldn’t even bring up his opponent’s Catholic religion (thereby bringing it up).

Nixon said if religion was to become an issue it would be “personally reprehensible to me. I can think of nothing more damaging to the country.”

Nixon wasn’t naïve. When the time was right, he could dredge up JFK’s inexperience, his health problems, and his extramarital affairs. Much of it was rumor, unfounded conjecture. But at that point, it didn’t matter.

For now, he was staying positive, saying he was prepared to stand on his record. “I always hit hard on the issues. I expect my opponents will do the same, but we must distinguish between issues and personalities,” he said.

That wasn’t always easy. On the issues side, Kennedy leveled relentless attacks on Nixon’s promise to continue Eisenhower’s policies.

“For I cannot believe that the voters of this country will accept four more years of the same tired politics,” Kennedy had said days earlier at a meeting of New York State Democrats.

“Four more years of neglected slums, overcrowded classrooms, underpaid teachers and the highest interest rates in history. And four more years of dwindling prestige abroad, dwindling security at home, and a collision course in Berlin.”

As for “personalities,” Kennedy wasn’t fooled by Nixon’s “take the high road” strategy. He reminded supporters of Nixon’s mudslinging tactics in past campaigns and said it would be a grave mistake if he tried to “out-Nixon Nixon.”

“Merely because Mr. Nixon is noted for personal abuse is no reason for our own campaign to follow suit. Merely because Mr. Nixon is known for his flexible principles, is no reason for ours to change,” Kennedy had told an audience in Fresno, California.

Right then, a book about Nixon’s life was a bigger threat than the sarcastic senator anyway. The Facts about Nixon: An Unauthorized Biography, by journalist William Costello, had been released on January 1 and zoomed to the top of the New York Times list of bestselling books.

Costello’s work was a frank appraisal of Nixon, an attempt to analyze his personality and potential. Nixon had no basic philosophy, he wrote—the vice president was a fatalist about politics who believed that men do not shape their times but are shaped by them.

“Political positions have always come to me because I was there, and it was the right time and the right place…It all depends on what the times call for,” Costello quoted Nixon as saying.

A large portion of the book dealt with the dirty campaign tactics he’d used in the past, earning him the unflattering sobriquet “Tricky Dick”—a nickname that had stuck.

When Nixon joined the Eisenhower presidential ticket in 1952, he stepped into the role of hatchet man, leveling vicious attacks against Democrats so that Ike could stay above the political fray.

Nixon wasn’t handsome. He was bland and had a perennial five-o’clock shadow. His broad nose and receding hairline made him look older than his age. Some thought he didn’t look presidential at all. He wasn’t a war hero, or rich. He was the average American—a hardworking, self-made man who was a little socially awkward, but driven to succeed. He shook everybody’s hand and said the right words to the camera. And for many Americans, stories of Nixon’s childhood and upbringing were fresh news, even after eight years in office.

Born on January 9, 1913, Richard Nixon was the second of five sons in a working-class family that lived in Yorba Linda, California. His parents were Quakers who struggled to make ends meet. They raised him in a staunchly conservative environment that prohibited alcohol or dancing. His father, Frank, had tried his hand at lemon farming, but when the enterprise failed, he moved the family down the road to Whittier and bought the gas station/grocery store.

From boyhood, family members and friends noticed that Nixon was serious, even gloomy. Maybe it was because he had to deal with tragedy at a young age; two of Nixon’s younger brothers died before he turned twenty. Nixon worked hard at the family store and studied hard at school. But he was argumentative, distrustful, and competitive. He lacked a sense of humor and was highly sensitive to any criticism.

Nixon resented those from more privileged backgrounds. After he graduated high school, Harvard University offered him a scholarship for tuition, but he didn’t have enough money to cover the rest of the costs. His family needed him to help at the store. So Nixon said no to the Ivy League and attended Whittier College, a Quaker school closer to home.

At Whittier, Nixon was elected student body president and played offensive tackle on the football team, which had a distinctly unthreatening nickname: the Poets. Nixon was undersized and got little playing time—one teammate called him “cannon fodder”—but he credited the game and his coach with building his tenacity.

Nixon was an excellent debater, training he had received at the dinner table when he argued with his father about current events.

After graduating from Whittier in 1934, Nixon attended Duke University School of Law on a scholarship. At Duke, he was surrounded by wealth. When he finished law school, Nixon interviewed at several prestigious East Coast law firms, but failed to land a position. Humiliated, he returned to Whittier to practice law.

Nixon blossomed back home. He joined the Whittier Community Players, a local theater group. He went to the casting tryouts for its 1938 production of The Dark Tower.

When Nixon walked inside the theater that night in January, he met a “beautiful and vivacious woman with Titian hair….” The new girl was Thelma Catherine Ryan, who had just started teaching at Whittier High School. Nixon was captivated.

Everyone called her Pat, a nickname her coal-miner father had given her because she was born just in time for St. Patrick’s Day in 1912.

When she was young, her father left the mines and moved to California to be a farmer. Her mother died of cancer when she was thirteen, so Pat helped raise her four siblings, worked at the farm, and thrived at Excelsior Union High School.

Her father died when Pat was eighteen, but nothing could deter her from her education. She found a way to continue with school, working odd jobs to pay for her tuition, first at Fullerton Junior College and then at the University of Southern California. She graduated with honors and landed a job teaching at Whittier High.

After the drama tryouts, Nixon drove Pat home and asked her out. Pat wasn’t interested. “I’m very busy,” she said.

But she let him drive her home after each play rehearsal. One night he told her, “You shouldn’t say that, because someday, I am going to marry you!”

Pat laughed. Was he joking around? But what Pat didn’t recognize was Nixon’s determination.

Pat was an outgoing, popular teacher. Nixon was an ardent suitor. He drove Pat on the weekends to her sister’s house in Los Angeles. He even chauffeured her to dates with other men and waited till the evening was over to drive her back. He didn’t give up.

Months after meeting him at the audition, Pat said she’d give Nixon a chance. He began sending her letters to express his love. He playfully called her his “Irish gypsy.”

Every day and every night I want to see you and be with you. Yet I have no feeling of selfish ownership or jealousy. Let’s go for a long ride Sunday; let’s go to the mountains weekends; let’s read books in front of fires; most of all, let’s really grow together and find the happiness we know is ours.

In another, Nixon described himself as “filled with that grand poetic music” in her presence.

A year after they met, Nixon was ready. He had picked the perfect spot: a patch of green high above the Pacific Ocean. And the basket filled with mayflowers in the car? It was just a ruse. Nixon had hidden an engagement ring underneath the white, bell-shaped flowers. When she found it, Nixon asked Pat if she’d marry him. She didn’t hesitate. She said yes. And so, they married on June 21, 1940.

The couple settled into Whittier, Pat continuing to teach and Nixon practicing law. After the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, Nixon landed a wartime job in the Office of Price Administration in Washington, D.C., but then joined the U.S. Navy. Although he did not achieve the heroics of Kennedy, Nixon rose through the Navy ranks, eventually becoming a commanding officer.

While on active duty, he continued to faithfully write letters to Pat, expressing his love.

This weekend was wonderful. Coming back I looked at myself in the mirror and thought how very lucky I was to have you…. I was proud of you every minute I was with you…. I am certainly not the Romeo type. I may not say much when I am with you—but all of me loves you all the time.

Before he was deployed to the South Pacific, he made a dinner reservation at the Rainbow Room in Rockefeller Center in New York City. He wanted them to dine “where we can sit with real silver, on a real tablecloth with someone to serve.”

His letters to her described the insecurities that plagued him, and his introverted character.

After he left the service, he successfully ran for the congressional seat representing Whittier in 1946. Within a couple of years, they had settled into family life and had two daughters.

In 1948, Nixon made national news when the U.S. House Un-American Activities Committee revealed that domestic communism wasn’t some existential threat to developing countries. No, communism was a danger here, to the security of the United States.

The case that catapulted Nixon to national attention centered on Alger Hiss. He had all the right credentials—and connections. A former State Department official, Hiss had attended Harvard Law School, served as a law clerk to Supreme Court justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, and advised President Franklin D. Roosevelt at the Yalta Conference in 1945.

But then Hiss was accused by Whittaker Chambers, a former U.S. Communist Party member, of being a spy who’d passed secrets to the Soviet Union. Hiss was a charming fellow. His stirring testimony forced the House committee to consider dropping the investigation, but Nixon said no. He stood his ground, and fellow senators put him in charge of a committee to investigate whether Hiss was lying.

Through Nixon’s persistence, the committee collected enough evidence to charge Hiss with perjury. They included the so-called Pumpkin Papers—materials Chambers testified Hiss had passed to him to deliver to a Soviet spy network. Instead, Chambers stored the materials on his Maryland farm.

It was something out of a spy thriller. Chambers had saved sixty-five pages of retyped secret State Department documents, four pages transcribed and handwritten by Hiss, and five rolls of developed and undeveloped 35mm film. He had wrapped the items in wax paper and stashed them inside a hollowed-out Halloween pumpkin.

Nixon was vindicated. Hiss was found guilty and served three years of a five-year sentence.

That—and Nixon’s victory in the U.S. Senate race in 1950—thrust Nixon into the national spotlight.

At the 1952 Republican National Convention in Chicago, party leaders told Eisenhower he should choose the thirty-nine-year-old Nixon as his running mate. Ike believed the party needed to promote young, aggressive leaders, so he signed on.

Nixon was an able congressman and senator, but he was chosen “not because he was right-wing or left-wing but because we were tired, and he came from California,” one party leader said later. California was strategic for an Eisenhower victory.

But before Eisenhower and Adlai Stevenson could face off in the November general election, ethical questions surfaced about Nixon. Critics said he had taken $18,000 from a supporter and spent it on personal items.

Now Nixon was in real danger of Eisenhower dropping him from the ticket. But Nixon did something extraordinary that would save his spot—and define his young legacy. He decided to fight the charges using the new untested power of television.

Television was relatively new but exploding in popularity. In just four years, the number of television sets in America had increased from around 350,000 to 15 million in 1952. To reach a wide audience quickly, Nixon would release his personal financial records in a live national broadcast. It was risky. No one knew what Nixon would say, or if anyone would even watch the speech.

Just before the cameras were set to roll, the evening of September 23, 1952, Nixon wasn’t sure he could do it. He expressed his fears to his wife, Pat. But she encouraged him.

“ ‘Of course you can,’ she [Pat] said, with the firmness and confidence in her voice that I so desperately needed,” Nixon recalled in Six Crises.

And then, with studio cameras on, Nixon calmly denied the allegations—except one. He said his family did receive a gift—a cocker spaniel named Checkers.

“You know, the kids, like all kids, loved the dog. And I just want to say this, right now, that regardless of what they say about it, we’re going to keep it,” he said.

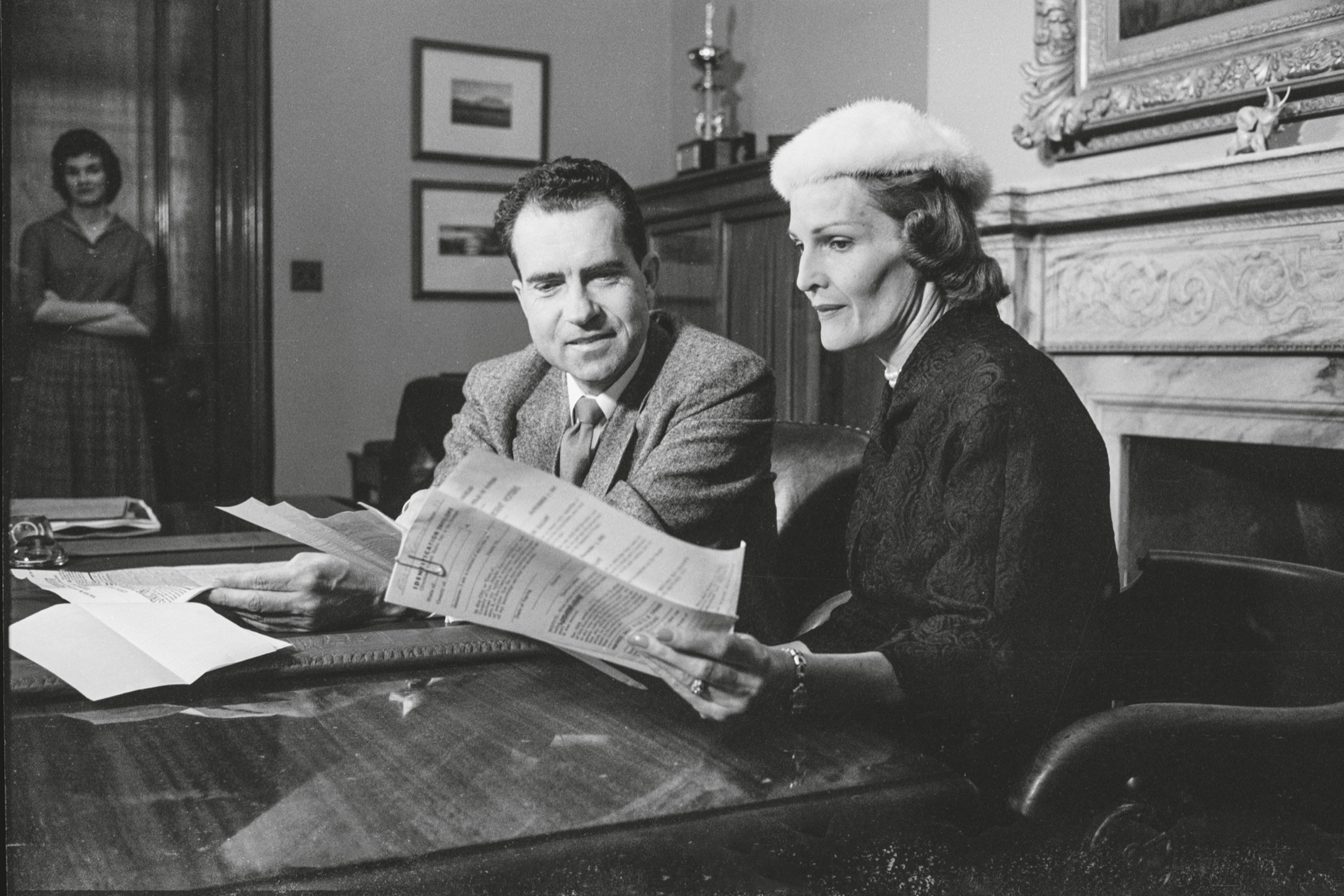

Richard and Pat Nixon, 1960

(Library of Congress, U.S. News & World Report Magazine Collection)

Cute little girls and puppies…Nixon’s speech was seen by a record television audience of 60 million Americans. The Checkers speech seasoned Nixon’s political experience and convinced him that “television was a way to do an end-run around the press and the political establishment.”

The Nixons kept their dog.

And Eisenhower kept Nixon on his ticket.

“You’re my boy,” Eisenhower said.

Nixon was Eisenhower’s boy in 1952, and the duo was reelected in 1956. But for much of the 1960 campaign, Eisenhower’s vice president didn’t feel he had the boss’s support.

He couldn’t get the president to publicly endorse him. Reporters asked the president several times if he supported Nixon’s candidacy, and each time Eisenhower declined to comment.

When he wasn’t in the White House, Eisenhower lived in a farmhouse in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. The president often invited friends to visit there—but never Nixon. The vice president quietly burned.

“Do you know he’s never asked me into that house yet,” Nixon griped.

It had been a long road, but now it was Nixon’s turn to run for the top spot on the GOP ticket. The Democrats were dominating newspaper and broadcast news coverage with their presidential horse race. Nixon was worried that he was fading into the background, that his campaign would lose momentum. That’s why trips like this one to Detroit were so important—he needed to build energy, to keep his supporters engaged and excited. Entering GOP primaries would keep his name in the news.

Nixon also placed himself on the ballot in the New Hampshire, Ohio, Oregon, and Wisconsin primaries. The move was designed to unify Republicans. By putting up a Nixon slate, the states’ GOP leaders pledged to work hard to roll up an impressive vote total for the vice president. If Rockefeller still had any thoughts of entering the race at the last minute, Nixon would have the nomination sewed up already.

Nixon was fed up with Rockefeller’s shenanigans. The New York governor’s camp was pressing him to declare himself a progressive. That wasn’t going to happen.

The “new Nixon” might’ve been a little more liberal than many of his GOP colleagues on civil rights, but he was a loyal conservative. Nothing was going to change that—especially now, when he had a clear shot to the White House.

Nothing was going to change the fact that Nixon had made a lot of enemies on his climb to the top, either. His closest friends and advisers knew it wouldn’t be smooth sailing, and that bad news had a way of breaking at the worst moment. But they hoped for the best and prepared for the worst, praying the Nixon campaign could hang on.