COUNTDOWN: 44 DAYS

September 26, 1960

Chicago, Illinois

As darkness fell over Chicago, a limousine turned toward the entrance of the WBBM-TV television studio, where the first of the presidential debates would take place.

Richard Nixon rode in the back, his hands full of question cards and notes. He was prepared. He was a skilled debater from childhood, when he’d hashed out the issues of the day at the dinner table with his dad. He’d served on the debate teams in college and law school, and they’d prepared him well for world-class deliberation.

It was Nixon who held his own against Khrushchev in the so-called kitchen debate in Moscow in 1959. And Nixon knew how to use television. Hadn’t his Checkers speech in 1952 saved his political career?

Nixon had drilled down on the facts, arguments, and counterarguments for both sides of the top issues. He could then develop his own position, anticipate his opponent’s, and avoid errors of fact or logic.

Most important, he knew to keep calm and composed, maintain eye contact, use hand gestures, and stand up straight.

Nixon, however, was still feeling the effects of his knee injury. He had emerged from the hospital at least ten pounds lighter—and hadn’t regained the weight. To make matters worse, the vice president had recently battled the flu. He was still weak. But instead of resting before the debate, he made a campaign speech.

It didn’t matter that he felt physically run-down and low—or that his gaunt face and pale complexion made him look, as Don Hewitt, who directed the debate for CBS, described it, “like death warmed over.” He knew he had this debate in the bag. Besides, his psychiatrist, Arnold Hutschnecker, had advised Nixon how to stay calm under pressure.

The car rolled to a stop. An assistant opened the door. Nixon stepped into the warm evening—and slammed his barely healed knee into the edge of the car door. He clutched his leg in pain—and could barely stand.

Nixon’s longtime media adviser, Ted Rogers, saw Nixon’s face turn white. But the vice president waved away his aides’ helping hands. He was okay, he said. He wouldn’t let this get to him. He’d fight through the pain. Tonight was too important.

Clearly it wasn’t a good start to the evening.

There were plenty of people who thought Nixon should skip the debates, that they would only give Kennedy more visibility. But backing down wasn’t an option. Nixon wasn’t a quitter. This was the most anticipated political event of the presidential campaign, and Nixon was sure he was up to the challenge.

The idea of broadcasting presidential debates had taken hold months earlier—well before Nixon and Kennedy became their parties’ candidates.

It took congressional action to make it happen. Section 315 of the Federal Communications Act of 1934 required broadcasters to allow political candidates equal time to present their views. Democrats and Republicans would have to share the debate stage with third-party candidates, and the events would drag on for hours—unthinkable within the tightly programmed TV format.

Congress passed a resolution to suspend the rule in late July, and Eisenhower signed it on August 24.

Television had brought new awareness and enthusiasm to the political process. In 1950, around 10 percent of the nation’s families owned a television. Now, in the fall of 1960, more than 90 percent of American families owned at least one set, a total of some 50 million TVs. The average American watched four to five hours of television every day.

And the Kennedy-Nixon face-off had the potential to be riveting. Both were experienced debaters. In fact, they had squared off long before, in 1947, when they were first-term members of the House of Representatives.

During their early days in Congress, they were appointed to the Education and Labor Committee.

In April 1947, they traveled by train to McKeesport, Pennsylvania, to debate the pros and cons of the Taft-Hartley Act, a law designed to significantly reduce the power of organized labor. The legislation would prohibit certain kinds of strikes and give workers the option of joining a union instead of forcing them. It had already passed the House and was before the Senate.

A coal-and-steel town of about 45,000 people outside Pittsburgh, McKeesport was the perfect location to debate the issue. The United Steelworkers, one of America’s most powerful unions, was based in Pittsburgh.

A civic group sponsored the debate at the Penn-McKee Hotel. They picked Nixon and Kennedy because they were considered rising stars in their respective parties. No surprises. Nixon spoke in strong support of the bill; Kennedy was opposed. Most of the pro-union crowd seemed to favor Kennedy, who’d later admit that Nixon won that debate: “The first time I came to this city was in 1947, when Mr. Richard Nixon and I engaged in our first debate. He won that one, and we went on to other things.”

After the debate, they headed to a local diner, where they bonded over burgers and baseball. Then they dashed off to the train station to catch the eastbound midnight train to Washington. They shared a compartment and had to flip a coin for who got the lower bunk; Nixon won that, too. Thirteen years later, they were together again on the debate stage, this time competing for the most powerful office in the world.

In midsummer, just before the start of the GOP convention, Robert Kintner, the president of NBC, had approached them about a debate, saying he’d reserved up to nine hours in prime time for a series of presidential debates. Would Kennedy be interested?

“I know the decision was made in 15 to 20 minutes that we should send a telegram to Kintner saying we accepted,” Salinger recalled. “The feeling was, we had absolutely nothing to lose by a debate with Nixon. In fact, if we accepted right away, we put Nixon in a position where he had to accept.”

For Salinger, it seemed like the perfect offer at the perfect time. Kennedy had been campaigning hard. People might have tuned in for his speeches, or noted his face on the covers of many magazines, but most “average Joe” Americans still didn’t know what Jack Kennedy stood for. The debates would introduce him to a new audience, the prime-time TV viewer. Since there were only three networks—no cable television yet to dilute the audience—the debate would saturate the airwaves.

And TV brought JFK another advantage. Just standing up next to Richard Nixon would show the world that it was Kennedy who looked like a statesman—and Nixon a politician.

The timing was perfect. Kennedy was on top of his game, sharpened by the campaign stops and stump speeches. People could feel his passion. His campaign ads were like nothing ever seen before, and the Rat Pack was out in full force, keeping the Kennedy image in the spotlight.

He looked and sounded physically fit, even if he owed that to special injections from Max Jacobson, a doctor to the stars, whom author Laurence Leamer described in The Kennedy Men as “a wondrous doctor who gave his patients magical vitamin injections that contained, among other things, the blood of young lambs.” Kennedy had been on the verge of collapse when his friend Charles Spalding told him about Jacobson, whose Manhattan waiting room was full of celebrity patients like Eddie Fisher, Truman Capote, and Johnny Mathis.

Kennedy paid a visit to the doctor in early September, complaining that his muscles felt weak and his energy was low. Jacobson injected JFK with a mixture of amphetamines, steroids, and vitamins. It gave Kennedy the boost he needed for his Houston speech to the group of ministers. A second shot promised to give him an edge in Chicago.

Meanwhile, Republicans weren’t sure about televised debates. But Kennedy had already agreed to participate. What would the public think if Nixon said no? Besides, Nixon enjoyed a good debate. He was confident in his ability.

Nixon didn’t run the question past his advisers. He just said yes. It was another example of the vice president making important campaign decisions on his own, without consultation, like the New York meeting with Nelson Rockefeller and the pledge to campaign in all fifty states.

His aides were flummoxed. Advance man H. R. Haldeman recalled that he didn’t believe Nixon was physically ready for the debate.

“I was concerned because I knew he…looked bad physically and was in bad health. He was not in good physical shape and, therefore, not good mental shape, I didn’t think. He wasn’t ready to do the job in the debate,” he said.

But Haldeman didn’t help Nixon by not scheduling time to meet with Ted Rogers in the days leading up to the debate.

Originally a producer for television shows like The Lone Ranger, Rogers had been with Nixon since his Senate race in 1950. On the day of the debate, Rogers didn’t see Nixon until 4:30 p.m. And when he did, he was stunned at the vice president’s appearance.

Still, Nixon felt that he could handle Kennedy. JFK didn’t have his experience, his skills. Nixon believed he’d win, and it wouldn’t be close.

The format had been settled in advance. The candidates would stand alone, without advisers, without a studio audience.

Howard K. Smith of CBS would serve as the moderator, opening and closing the program. At the outset, each candidate would have eight minutes to state his case, with a coin flip deciding who’d go first.

Then for about forty minutes, a panel of television journalists would ask questions. Each candidate would be allowed three minutes for his reply, after which his opponent would get a minute and a half to respond. This debate would be limited almost completely to domestic affairs.

This was another Nixon miscalculation. He believed the audience for the debates would build—so that viewership would peak later. At the third debate, the focus would be on foreign policy issues, Nixon’s strength. What he didn’t realize was the first debate would have the biggest impact on voters’ perceptions—and domestic issues were in Kennedy’s wheelhouse.

The networks selected no newspaper reporters for the panel. And only those who’d traveled with the campaigns could attend the live event—and they had to watch the action on monitors from an adjacent studio. The networks predicted that between 50 and 80 million people would watch the first debate.

NBC would handle the second one on October 7, and ABC would carry the last two on October 13 and October 21.

Robert Kennedy knew the debates would play to his brother’s on-camera poise and good looks. Hiring a professional media consultant was paying dividends. TV viewers were already used to seeing Kennedy on their screens.

The Nixon campaign was optimistic, too. Press secretary Herb Klein knew Nixon felt he could debate anyone. And if the vice president avoided the debates, he’d be “hounded by it by the hostile press.”

The first debate was scheduled for a Monday night. Kennedy arrived from Cleveland, Ohio, the day before and stayed at the Ambassador East Hotel in Chicago.

Ted Sorensen, Richard Goodwin, and Mike Feldman, Kennedy’s “brain trust,” had prepared fifteen pages of relevant facts and probable questions. On Monday morning, they held a question-and-answer session with Kennedy: What was the latest unemployment rate? What were Nixon’s ideas for improving schools? It was light and easy. No tension.

They helped Kennedy with his eight-minute opening statement, but in the end, JFK rewrote it.

Kennedy headed to a gathering of the United Brotherhood of Carpenters union, then returned to the hotel for a nap. According to Theodore White in The Making of the President 1960, when he got up around 6:30 p.m., he was refreshed and ready to go. He read the cards with facts and figures that Sorensen, Goodwin, and Feldman had prepared for him. He ate dinner on his own, and put on a dark blue suit and white shirt and dark tie. Then he headed to the studio.

Meanwhile, Nixon had spent most of the day with only his wife, Pat, alongside him. As usual, Nixon took it upon himself to do just about everything. His advisers had urged him to get to Chicago early the day before the debate so he could rest. Instead, his limo pulled in at night, and he was running a fever—the lingering effects of the flu.

Nixon’s advisers had suggested he cancel his appearance the day of the debate before the carpenters union—hell, they were pro-Kennedy, and Nixon needed time to prepare. But Nixon went anyway. By the time he returned to his hotel room just after noon, he was exhausted.

Nixon locked himself in his suite and pored over campaign issues and questions he might be asked by the panelists. He took a telephone call from Henry Cabot Lodge Jr., who urged the vice president to go easy, to try to free himself of the “assassin image” he had built up over the years.

On the way to the television studio, Rogers, his media adviser, suggested just the opposite. He said Nixon should come out swinging. Like a good boxer, he said, Nixon had to hit Kennedy hard from the beginning.

But Nixon could hear Lodge’s voice in his head. This was a different Richard Nixon. Maybe he could put an end to “Tricky Dick.”

Rogers was worried. The vice president didn’t look well. Worse, he didn’t seem to grasp how stressful things were going to get.

When Nixon struck his bad knee on the door of the limousine, Rogers winced.

Once inside the studio, Nixon and his men looked around the set. The background was light gray—and Nixon’s blue-gray suit blended into the backdrop.

Nixon was sitting in a chair beneath a microphone for a sound check. When Jack Kennedy walked in, cool, slim, and tanned, Nixon stood to speak to him. He struck his head against the microphone, and the amplified impact boomed through the studio.

Maybe Nixon should have gone home then and called it a night. Things only got worse.

Producer Don Hewitt asked Kennedy if he needed makeup, and he said no. Nixon also refused the offer, but Hewitt could see that was a problem. Nixon looked tired. He had a five-o’clock shadow that he was trying to conceal.

As Kennedy headed to the set, his brother Bobby whispered some advice: “Kick him in the balls,” he said, with a mischievous smile.

The candidates stood in their places and took deep breaths while the moderator, Howard K. Smith, sat down behind a desk. The red light went on. It was showtime.

First presidential debate, September 26, 1960

(UPI/Newscom)

The studio was strangely hermetic, with a handful of panelists and technicians, and the candidates standing in a pool of light. But outside, 70 million viewers were watching in homes, churches, or bars—wherever there was a television set. It was the largest TV audience for a political event in history, to that point. The debates had preempted The Andy Griffith Show on CBS, the network’s most popular series. Millions more listened on radio.

Kennedy went first; and while the debate’s focus was supposed to be on domestic issues, JFK weaved the Soviet threat to the United States into his opening statement. He was unhappy, he said, with the way things were going in America.

“Are we doing as much as we can do? Are we as strong as we should be? Are we as strong as we must be…? I should make it very clear that I do not think we’re doing enough, that I am not satisfied as an American with the progress that we’re making,” he said.

Nixon challenged that in his opening statement. He said the nation was on the move, that it had racked up more progress in numerous fields in the Eisenhower administration than under former president Truman.

Kennedy stayed on the offensive. The bright lights didn’t help Nixon. He was sweating. He looked tired and ill. He had circles under his eyes.

“My God, they embalmed him before he even died,” Chicago mayor Richard Daley said at the time.

During the debate, Kennedy emphasized the differences between himself and Nixon. He hit on his main campaign themes: American economic growth needed to be increased. Teachers were poorly paid. The elderly could not support themselves on their Social Security checks. Kennedy hammered at the Eisenhower administration’s failures, while Nixon touted its successes.

But it was more than that. It seemed that Nixon was too polite. He’d often preface his answers by saying he agreed with the Massachusetts senator.

When a reporter asked Kennedy why people should vote for him when Nixon said he was too inexperienced for the job, JFK pointed to the fact that he had served in Congress the same length of time as Nixon—nearly fourteen years. “So, our experience in government is comparable.”

Besides, he said, the questions that counted were the programs the two advocated and the records of the two political parties.

Staring straight into the camera, JFK reminded the audience that the Democratic Party had supported and sustained important programs that helped the people.

John F. Kennedy at the first debate

(Associated Press)

“Mr. Nixon comes out of the Republican Party. He was nominated by it. And it is a fact that through most of these last twenty-five years the Republican leadership has opposed federal aid for education, medical care for the aged, development of the Tennessee Valley, development of our natural resources. I think Mr. Nixon is an effective leader of his party. I hope he would grant me the same,” Kennedy said.

Nixon had a chance at rebuttal and passed it up: “I have no comment.”

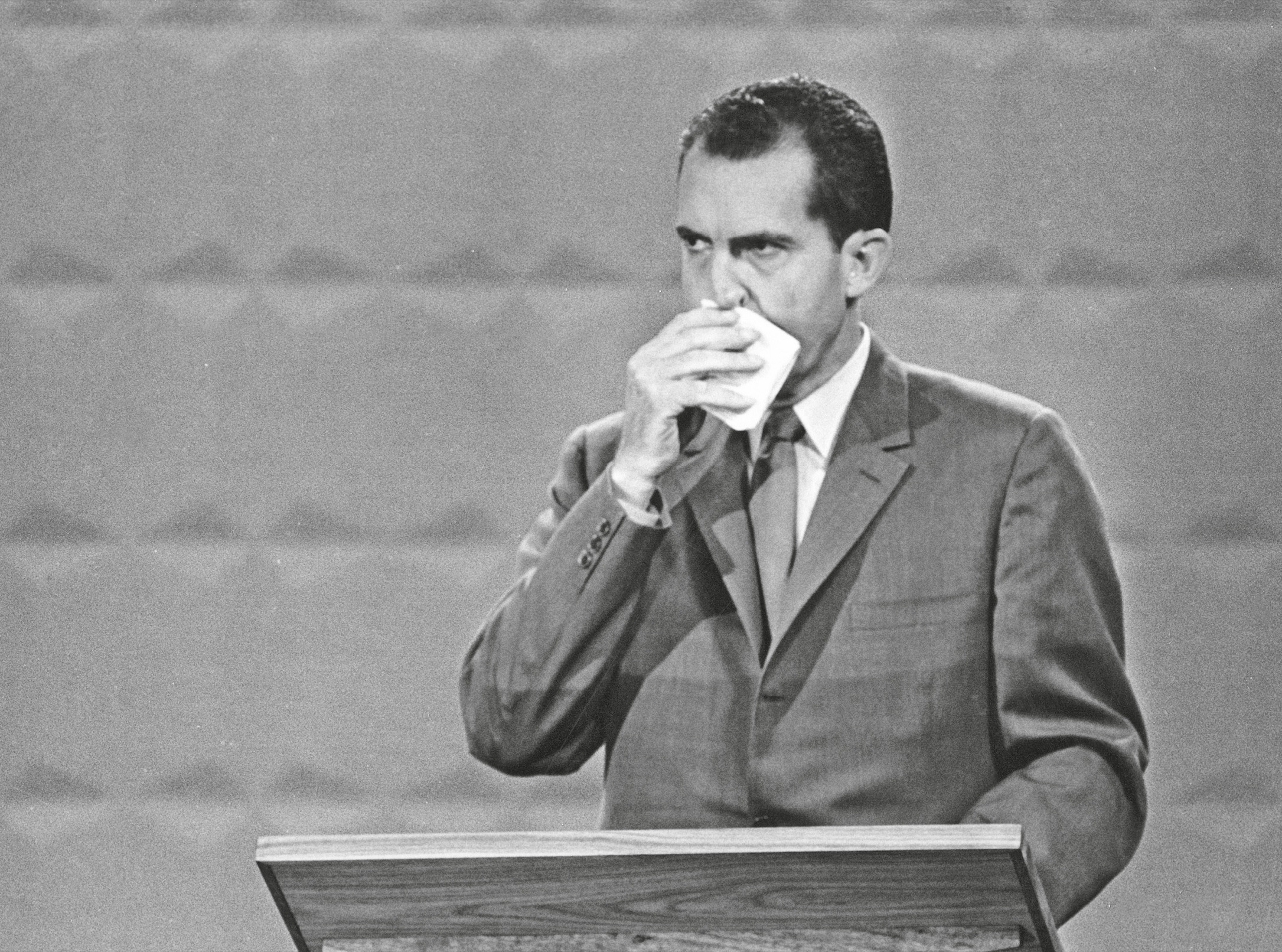

It wasn’t only Nixon’s answers, or nonanswers. It was the way he looked and acted on camera. There were times he seemed uncomfortable. He used a handkerchief to wipe sweat off his face. Was he nervous? Was it the hot lights of the studio? Was it his fever? Viewers wouldn’t have known about that.

By contrast, Kennedy seemed at ease. He’d stare into the camera, making it feel like he was talking directly to people in their living rooms. Meanwhile, his rival would often look off to the side to address various reporters. To television viewers, it felt like Nixon was trying to avoid eye contact with them.

Sander Vanocur of NBC News brought up Eisenhower’s “give me a week” comment of a few weeks earlier, about Nixon’s apparent lack of contributions to his administration.

Nixon was annoyed—he felt Vanocur had raised the question to hurt his campaign. He said the president was probably being “facetious when he made the remark.” He said he had advised Eisenhower on many issues, but in the end, the president made the decisions.

Nixon at debate

(Associated Press)

Kennedy responded that the real issue was “which candidate and which party can meet the problems that the United States is going to face in the ’60s.”

In his closing statement, Nixon said he concurred with Kennedy that “the Soviet Union has been moving faster” than America in terms of economic growth. But that was because they started “from a much lower base.”

And Nixon said he agreed “completely” with Kennedy that “we have to get the most out of our economy.”

“Where we disagree is in the means that we would use…. I respectfully submit that Senator Kennedy too often would rely too much on the federal government, on what it would do to solve our problems, to stimulate growth,” he said.

Nixon predicted that JFK’s programs would lead to higher prices for average Americans—and “people who could least afford it—people on retired incomes, people on fixed incomes.”

“It is essential that a man who’s president of this country certainly stand for every program that will mean for growth. And I stand for programs that will mean growth and progress. But it is also essential that he not allow a dollar spent that could be better spent by the people themselves,” he said.

When it was Kennedy’s turn, he spoke directly to viewers with more passion than at any time during the debate: If you feel America is headed in the right direction, you should vote for Nixon. But if you don’t, you should vote for me.

“I don’t want historians, ten years from now, to say these were the years when the tide ran out for the United States. I want them to say these were the years when the tide came in; these were the years when the United States started to move again,” he said.

At the end of the debate, Nixon greeted Kennedy. But in full view of the still photographers, Nixon jabbed his finger into Kennedy’s chest as if he were “laying down the law about foreign policy or communism,” Kennedy recalled.

The image was not of a commander. No, it was more like a schoolyard bully. In fact, throughout the entire debate, Kennedy came across as an energetic leader, while Nixon appeared old, tired, and stuffy.

The debate succeeded in erasing, in one night, the stature and experience advantage Nixon had enjoyed throughout the campaign. Kennedy had appeared to be the vice president’s equal. In debate one, Kennedy bested Nixon because he was more relaxed and more in command of the issues, and because he didn’t look sick or sweaty.

When it was over, Henry Cabot Lodge Jr., who was watching in his hotel room in El Paso, Texas, with several reporters, including Tom Wicker of The New York Times, made a harsh instant analysis about the man on the top of their ticket: “That son of a bitch just lost the election,” he said.