Around 5,000 years ago, settled agricultural communities of the late Bronze Age began to coalesce into recognisable, socially organised civilisations in three distinct regions of the globe. The earliest of these emerged prior to 3000 BC in the Fertile Crescent, which stretches in a hoop from Upper Egypt along the Eastern Mediterranean coast, and down the Tigris-Euphrates valley to the Persian Gulf. Similar developments would occur around 2500 BC in the Indus Valley (loosely modern Pakistan) and half a millennium later along the Yellow River in China. Central to all these regions are great rivers, which irrigate the land and are prone to flooding. Herodotus, ‘the father of history’, writing in the fifth century BC, offers one of the earliest descriptions:

During the flooding of the Nile only the towns are visible, rising above the surface of the water like the scattered islands of the Aegean Sea. While the inundation continues, boats no longer keep to the channels and rivers, but sail across the fields and plains.

In distant history, such an inundation had evidently become a catastrophic deluge, carrying away all in its path. Thus it comes as little surprise that the early mythology of each of these separate civilisations speaks of a great flood which God caused to cover the earth, with only a chosen few surviving. In the biblical version, it is Noah and his family who survive, along with their ark, which contained ‘two and two of all flesh’ including ‘every beast . . . and all the cattle . . . every creeping thing that creepeth upon the earth . . . and every fowl [and] every bird.’ When the Flood subsided, Noah’s ark is said to have run aground on Mt Ararat, which is located in the far east of modern Turkey, close to the borders with Armenia and Iran, at the very upper reaches of the Euphrates river basin.

At the opposite ends of the Fertile Crescent, in Egypt and in Mesopotamia (loosely modern Iraq), two distinct civilisations began to develop. In Egypt, the so-called Old Kingdom began in 2686 BC with the unification of the Upper and Lower Kingdoms. Perhaps half a millennium prior to this, the Sumerian civilisation attained maturity in the fertile region between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, which during this period flowed separately into the Persian Gulf.1 Technological innovations which took place within the Fertile Crescent include the development of agriculture and the introduction of irrigation, as well as the invention of glass-making and the wheel.

Writing was invented by the Sumerians. Originally this consisted of round marks made in damp clay, which was then baked to become a permanent record – probably numbering cattle, containers of wheat and so forth. With the introduction of a wedge-shaped reed as a marker, these impresses evolved into cuneiform writings, with distinct characters, capable of conveying things and later the language itself. Sumerian, as spoken in southern Mesopotamia, is classified as a ‘language isolate’; in other words, it appears to be original, and not descended from any prior language – except perhaps an early verbal Paleolithic pidgin. The Sumerians inhabited independent city states, whose populations probably extended to around 20-30,000 inhabitants each. The territorial boundaries of these states were marked out by canals and boundary stones. In the view of most authorities, the Sumerians may have constituted a civilisation, but they were not an empire. Yet it was out of this innovative civilisation that the Akkadian Empire (2334–2154 BC)would grow.

One of the earliest references to Akkad is in the Book of Genesis, the first book of the Bible. This records that Nimrod, the great grandson of Noah, founded a kingdom which included Babel and ‘Accad’. According to myth, Nimrod was responsible for building the Tower of Babel, a structure intended to be so high that it would reach heaven. This so angered God that he caused its builders to speak different languages, thus confounding their efforts, and dividing humanity into different language groups. Some myths also identify Nimrod with Gilgamesh, hero of the eponymous Epic, the oldest great work of literature known to us. From this, it can be seen that Nimrod is probably a mythical character, containing elements of several ancient heroes whose identity became blurred in prehistory.

The first historically certain ruler of the Akkadian Empire was Sargon, who was born around the middle of the twenty-third century BC. Though we do not know the actual birth-name of this individual: Sargon simply means ‘the true king’. Even details of Sargon’s life and reign remain disputed amongst scholars, necessitating choice, which once again leaves any historian open to the charge of valuing ethos over accumulated fact, incorporating often contradictory evidence.

Sargon’s legendary description of his infancy has familiar overtones:

My mother was a changeling [a child substituted by fairies for a human child], my father I knew not . . . She set me in a basket of rushes, with bitumen sealing my lid. She cast me into the river which rose not over me . . .

In this there are unmistakablea echoes of the infant Moses, the Hindu god Krishna, and Oedipus, as well as the Messiah. This would appear to be some kind of archetypal myth, a requisite for such early proto- or quasi-divine figures. Much like Moses almost a millennium later, Sargon was found, adopted and thrived in his new home, the kingdom of Kish, part of the original Sumerian civilisation. Sargon rose to the important post of maintaining the irrigation of the kingdom’s canals, in charge of a large band of labourers. These labourers were probably reserve militia, skilled in the use of weapons. At any rate, Sargon gained their loyalty, and they aided him in overthrowing the King of Kish, Ur-Zababa, around 2354 BC.

Soon after seizing power, Sargon succeeded in conquering a number of neighbouring Sumerian cities, including Ur, Uruk, and possibly Babylon. After every victory he ‘tore down the city walls’ and the city was incorporated into the Akkadian Empire. Sargon is said to have founded the capital Akkad (Accad, Aggade). According to one source, he ‘dug up the soil of the pit of Babylon, and made a counterpart of Babylon next to Agade.’ Here Sargon built his palace, set up his administration and barracks for his army. He established a temple to Ishtar (Akkadian name for the Sumerian goddess of fertility and war) and Zababa (the warrior god of Kish). Sadly, Akkad has yet to be discovered, and remains ‘the only royal city of ancient Iraq whose location remains unknown.’ This precludes any direct archaeological evidence, limiting our knowledge to the likes of Babylonian tablets and texts, often made many centuries later.

Sargon’s ambitions soon grew, and he would launch a number of campaigns – with the declared intention of extending his empire across the entire known world, as it was to him. This included the whole of the Fertile Crescent, no less. He did not ultimately succeed in this, but the extent of his conquests and military expeditions remains impressive all the same. The later Babylonian texts, known as the ‘Sargon Epos’, speak of him seeking the advice of his subordinate commanders before launching his ambitious campaigns. This suggests the commander of a well-run military machine, rather than a despotic ruler, or the megalomania implied by his territorial aims. Not surprisingly his feats entered later legend:

[Sargon] had neither rival nor equal. His splendor, over the lands it diffused. He crossed the sea in the east. In the eleventh year he conquered the western land to its farthest point. He brought it under one authority. He set up his statues there and ferried the west’s booty across on barges. He stationed his court officials at intervals of five double hours and ruled in unity the tribes of the lands. He marched to Kazallu and turned Kazallu into a ruin heap, so that there was not even a perch for a bird left.

Kazallu seems to have been one of Sargon’s earliest conquests, as it was probably located east of the Euphrates near Babylon. The ultimate extent of Sargon’s conquests remains impressive. His military exploits certainly took him as far as the eastern shores of the Mediterranean ‘up to the cedar forest and the silver mountain’. This is seen as a reference to the Ammanus and Taurus ranges, which stretch along the border of Anatolia (modern Turkey). Some legends suggest that he marched beyond this into Anatolia itself. This makes sense, as hostile tribes occupied the passes through these mountains, thus controlling the Akkadian trade routes to Anatolia, Armenia and Azerbaijan from which they received their supplies of tin, copper and silver.

The presence of such tribes may also account for why Sargon launched his southern military expeditions, which would have secured trade routes to these same metals in south-east Persia and Oman. This, or a further campaign into eastern territory, would also have protected access to the lapis lazuli which originated in north-east Afghanistan. This semi-precious stone, whose intense blue colour was much valued, could be polished for use in beads, amulets and inlays for statuettes. The extent of Sargon’s southern military expeditions is known in more detail. He is said to have ‘washed his weapons in the sea’, i.e. the Persian Gulf.2

Sargon’s southern conquests extended along the northeastern shores of the Persian Gulf as far as the Straits of Hormuz. Records of another expedition have him extending his empire along the south-western shores of the Gulf as far as Dilmun (modern Bahrain) and Magan (Oman). Such feats may seem extraordinary, but they remain plausible. Sargon is said to have maintained a standing army-cum-court of 5,400 men, ‘who ate bread daily before him’. Later texts speak of him setting sail across the Sea of the West (the Mediterranean) and reaching Keftiu, or Caphtor as it is called in the Bible. This is usually taken to be Cyprus, or possibly even Crete. Such was Sargon’s empire that he is said to have declared: ‘Now, any king who wants to call himself my equal, wherever I went, let him go!’

As we shall see, the leaders (and citizens) of most consequent great empires will harbour similar grandiose sentiments, which resonate through the millennia, mocking, and yet later mocked by, those who follow. This paradox is perhaps best illustrated by Shelley’s poem on ‘Ozymandias, king of kings’, who boasted, ‘Look on my works, ye mighty, and despair. ‘Yet all that now remained of these works was a vast broken statue and its half buried, shattered stone head, beyond which ‘boundless and bare the lone and level sands stretch far away’. Sargon was the first Ozymandias.3 And the lesson has yet to be learned, even today. From the Roman emperors to Napoleon, Hitler and beyond, dreams of imperial greatness remain rooted in a present which extends into perpetuity.

Babylonian copies of inscriptions that are known to date from the early Akkadian era claim that Sargon ruled over his empire for fifty-five years (c.2334–2279 BC). His extension of territory certainly aimed at more than mere conquest and devastation, as in the case of Kazallu. In many cities he appears to have spared the indigenous population, replacing the local government with Akkadian administrators. Likewise, the previous ruler would be executed and a trusted deputy installed in his place. With devastated cities such as Kazallu, the remnant population would either be put to the sword, or marched off in captivity to become slaves, in much the same manner as the Bible describes the Israelites being led into captivity in Babylon over one and a half millennia later.

In Sargon’s early conquests of Sumarian cities, he is said to have placed his daughter Enheduana as high-priestess of the moon god Inanna in Ur, and extended her role to high-priestess of the god of heaven, An, at nearby Uruk. Enheduana was evidently well suited for such roles, and she is known to have written a number of hymns to these Sumerian gods, which played a significant role in winning over the local population to her father’s rule. As such, she stakes a remarkable claim:

Sargon’s daughter made herself the first identifiable author in history, and the first to express a personal relationship between herself and her god.

These are two highly significant steps in our social individuation. Previously worshippers had grovelled in fear before their gods. Enheduana establishes herself as more than a mere priest. She wishes to be taken as a person, an interlocutor with the gods. She speaks to them personally, telling them what is happening in their cities. When a certain Lugal-Ane leads a rebellion at Ur, she asks Inanna to pass on a message to An, asking him to right these wrongs and come to her aid:

Wise and sage lady of all foreign lands,

Life-force of the teeming people:

I will recite your holy song! . . .

Lugal-Ane has altered everything,

He has removed An from E-Ana temple . . .

He stood there in triumph and drove me out of the temple.

He made me fly like a swallow from the window;

My life-strength is exhausted . . .

My honeyed mouth became scummed.

Tell An about Lugal-Ane and my fate!

May An undo it for me!

Note how Iananna, initially goddess of the city of Ur, is addressed as ‘lady of all foreign lands’, suggesting that her rule now extends over all her father’s conquests.The significance of this will become apparent later. At any rate, Enheduana’s prayers are answered, the rebellion is overcome, and she is reinstated, whereupon she addresses a profuse hymn of praise to Inanna: ‘My lady beloved of An . . .’

However, such a rebellion was not an isolated incident. As Sargon grew older, his grip on his empire was thought to be faltering. According to a late Babylonian chronicle: ‘In his old age all the lands revolted against him, and they besieged him in Agade.’ But Sargon was still prepared to rouse himself against ‘any king who wants to call himself my equal’. From his besieged capital he launched a furious counter-attack: ‘he went forth to battle and defeated them; he knocked them over and destroyed their vast army’. Later, the nomadic hill tribes of upper Mesopotamia rose against him, and ‘in their might attacked, but they submitted to his arms, and Sargon settled their habitations, and smote them grievously’.

As we shall see, this tendency to revolt in the outer regions of the Akkadian Empire would become a regular feature in the later years of a ruler’s life. Sargon was succeeded by his son Rimush, whose accession was greeted by a further revolt amongst the Sumerians and further afield in Persia. Although Rimush forcefully subdued these uprisings, he appears to have been a weak and unpopular character. Ultimately, he even forfeited the loyalty of his own courtiers. In 2270 BC, after nine years of rule, ‘his servants killed him with their tablets.’ As the twentieth-century French historian, Georges Roux, wryly comments, this ‘is proof that the written word was already a deadly weapon’.

Ramish’s successor to the throne was Manishtushu, whose name means ‘Who is with him?’ Roux suggests that this indicates he was Ramish’s twin brother. He too appears to have appointed his daughter as a high-priestess, which would suggest that this was becoming customary. The main event of Manishtushu’s reign was a great campaign he led south to the Persian Gulf:

Manishtushu, King of Kish . . . crossed the Lower Sea [Gulf] in ships. The kings of the cities on either side of the sea, thirty-two of them assembled for battle. He defeated them and subjugated their cities; he overthrew their lords and seized the whole country as far as the silver mines. The mountains beyond the Lower Sea – their stones he took away, and he made his statue . . .

Access to the trade routes in the south was once again open, giving access to metals and lapis lazuli. This was just as well, for by now the northern territories of the empire had slipped from Akkadian grasp, their lands overrun by hostile neighbours.

After a fourteen-year rule, Manishtushu would be succeeded by his son, Narâm-Sin, whose name translates as ‘Beloved of [the people of] Sin’. He would prove to be a great ruler, in the mould of his grandfather; his thirty-six-year reign (2254–2218 BC) inspiring many legends of his greatness. Having inherited the title ‘King of Agade’, Narâm-Sin would later add ‘King of the Four Regions (of the World)’, eventually ascending to ‘King of the Universe’, with his written name preceded by the star, ideogram meaning ‘god’, which in Sumerian reads as dingir, and in Akkadian as ilu.

This brings us to the difficult question of language. Although both the Akkadians and the Sumerians were Semitic peoples, they spoke distinctly different languages. It was Sargon who introduced Akkadian as the official language of government administration and imperial trade. Akkadian is the first Semitic language of which we have written evidence, and its main dialects appear to have been Babylonian and Assyrian. However, the original Sumerian remained the ceremonial and religious language. This was possibly because the Akkadians tended to adopt the gods of conquered territories, yet at the same time appointing female members of the royal family as their high-priestesses to ensure religious loyalty.

This transformation of the Akkadian language meant that it would become the spoken language throughout the empire. On the other hand, some scholars insist that Sumerian was retained and that the Akkadian Empire saw ‘widespread bilingualism’. As we have seen, Sumerian was a ‘language isolate’, whereas Akkadian was an East Semitic language – one of six groups in the Semitic language as a whole, which itself spread over the Levant, the Middle East, the Arabian peninsula and the Abyssinian region.

The general use of Akkadian and East Semitic through the Akkadian Empire led to ‘stylised borrowing on a substantial scale, to syntactic, morphological and phonological convergence’. Indeed, Akkadian would remain the lingua franca throughout the region until a millennium later, whence came the rise of Aramaic (the language spoken by Christ). Ironically, both Akkadian and East Semitic eventually became extinct, whereas the Semitic languages as a whole would evolve into widespread use in such varied languages as Phoenician, the Punic language of Carthage, as well as Arabic, Amharic (Ethiopian) and Hebrew.4

The imperial administration was funded by taxes on vassal city states, which were also required to maintain Akkadian garrisons. Domination was further maintained by the royal monopoly on foreign trade, as well as the awarding of estates in conquered territory to what is best described as Akkadian aristocracy. These were mostly former military commanders and trusted administrators, who would also be rewarded with slaves originating from other conquered cities. This had the added advantage of dispersing members of any potential clique who might attempt to overthrow their supreme ruler.

The power of the imperial ruler was further reinforced by his elevation to divine status. This had the effect of enhancing his personal charisma. It is difficult to over-stress this element of ‘leadership-charisma’, which would be a recurrent feature of empires. Emperors would be descended from the divine members of their family, thus assuming deity. Mere mortals who trembled in the emperor-god’s presence could never escape his wrath, even in the afterlife.

One of the great early Akkadian inventions was Sargon’s calendar, which was used throughout the empire. Sargon would name each year after an important event which had taken place during the previous year, and this became a standard tradition:

The year when Sargon went to Simurrum,

The year when Naram-Sin [sic] conquered . . . and felled cedars on Mount Lebanon.

Thus all city records were synchronised with those of Akkad. Before this, each city worked according to its own calendar – though in some cases religious events would coincide, owing to their dates coinciding with astronomical events, such as the equinox. Apart from its practical value, Sargon’s calendar was the most obvious symbol of a more pervasive imperial assimilation. Prior to conquest, each Sumerian city had used its own system of weights and measures, as well as distances. Under Sargon and subsequent rulers, all such measurements became standardised throughout Mesopotamia.5 This further cemented Akkadian rule, helping to establish a common way of life amongst the subject people. Furthermore, such was the success of this system that these were ‘units which would remain standard for over one thousand years.’

Towards the end of Narâm-Sin’s thirty-six-year reign, he became ‘bewildered, confused, sunk in gloom, sorrowful, exhausted’. The usual end-of-reign uprisings appear to have taken place in the outer provinces, most notably amongst the powerful Lullubi in Persia. Most inscriptions record that Narâm-Sin was victorious in these struggles, but this may include an element of rose-tinted hindsight. Other (admittedly incomplete) inscriptions speak of defeats, with Narâm-Sin only able to make a successful last stand at Agade. Either way, there is no denying that Narâm-Sin was ‘the last great monarch of the Akkadian dynasty’. His first notable victory over the Lullubi is commemorated in a fine rock sculpture, which can still be seen near a mountain-top in modern Iran at Darband-i Gawr (Pass of the Pagan).

More pertinently, he is also depicted in a superb victory stele, which was discovered at Susa, north of the Persian Gulf. This has deservedly been characterised as ‘a masterpiece of Mesopotamian sculpture’. Besides its realistic depiction in relief of surprisingly lifelike human figures, it has a number of significant features. For instance, Narâm-Sin is depicted as being almost twice as tall as the other human figures beneath him, and he is wearing a two-horned helmet, a sign of his divinity. (Later, this would become the sign of a minor deity; as a major deity, his helmet would sprout four horns.)6

Such regular end-of-reign uprisings allow us to make certain deductions. As the twentieth-century author Paul Kriwaczek pointed out:

Empires based solely on power and domination, while allowing their subjects to do as they will, can last for centuries. Those that try to control the everyday lives of their people are much harder to sustain.

Such considerations certainly help account for the brevity of this first empire, which lasted for less than two centuries.7 The Akkadian imposition of alien gods upon their conquered cities would seem to have been but the outward manifestation of a more heavy-handed communal control. Even so, other factors must certainly have contributed. For a start, the sheer novelty of this highly complex human-social creation must certainly have made it difficult to sustain. Obvious though it may seem, one should always bear in mind the sheer difficulty presented by the fact that the Akkadians had no blueprint for what they were doing. They were obliged to make up the rules as they went along.

Following the death of Narâm-Sin in 2218 BC, he was succeeded by his son, Shar-kali-sharri (‘King of All Kings’), who would rule for the next twenty-five years. Shar-kali-sharri appears to have presided over a period of almost continuous provincial revolts, even one by the governor of Elam, who had been appointed by his father. In 2193 BC, Shar-kali-sharri would be murdered in a palace revolt, whereupon the empire descended into anarchy. The Sumerian King List, which was compiled around 2100 BC, evocatively says of this period: ‘Who was king? Who was not king?’

Excavations carried out at the end of the twentieth century indicate that from c.2220–2000 BC the entire Eastern Mediterranean region was subject to a severe climate change, bringing with it droughts and famine. During this period, fertile regions in Sinai became deserts, and archaeological evidence indicates that ‘nearly all Palestinian . . . towns and villages were destroyed around 2200 BC and lay abandoned for about two centuries.’ Some posit a sensational explanation for this climate change: ‘Aerial photographs of southern Iraq revealed a two-milewide circular depression with the classic hallmarks of a meteor crater.’ This would possibly explain recent archaeological evidence that on some sites there was ‘construction seemingly going well when, apparently overnight, all work suddenly stopped.’

Either way, this change marked the end of the Akkadian Empire, regarded by many as ‘The First World Empire’.

However, not all concur with this assessment. The twentieth-century Italian scholar, Mario Liverani, vehemently insists: ‘In no case is the Akkad empire an absolute novelty [. . .] “Akkad the first empire” is therefore subject to criticism not only as for the adjective “first” but especially as for the noun “empire”.’ Liverani argues that earlier the Sumerians developed ‘proto-imperial states’, adding somewhat anomalously that the term ‘empire’ with regard to the Akkadians is ‘simplistic’.

This argument is convincingly countered by Kriwaczek, who points out a fundamental transformation that came about with this ‘first empire’: ‘Up until now, civilisation based itself on the belief that humanity was created by the gods for their own purposes . . . Each city was the creation and home of a particular god.’ With the conquests of Sargon, all this changed. This was how Inanna, goddess of the city of Ur, came to be addressed by Sargon’s daughter Enheduana as ‘lady of all foreign lands’. The gods and goddesses of the rulers would become the supreme gods and goddesses of the entire Akkadian Empire.

The Akkadian world witnessed the proliferation, if not always the origin, of many features of early civilisation. Sophisticated realistic sculptures were carved in relief on stone stele, or gouged in relief into cylinders, which, when rolled, left an impression in clay. Similarly, silver gathered from mines at the outposts of the empire was melted into ingots. These were then stamped with a name (the seal of approval) and weight; they were thus used for trade: a proto-form of money, guaranteed by the world’s first bankers.

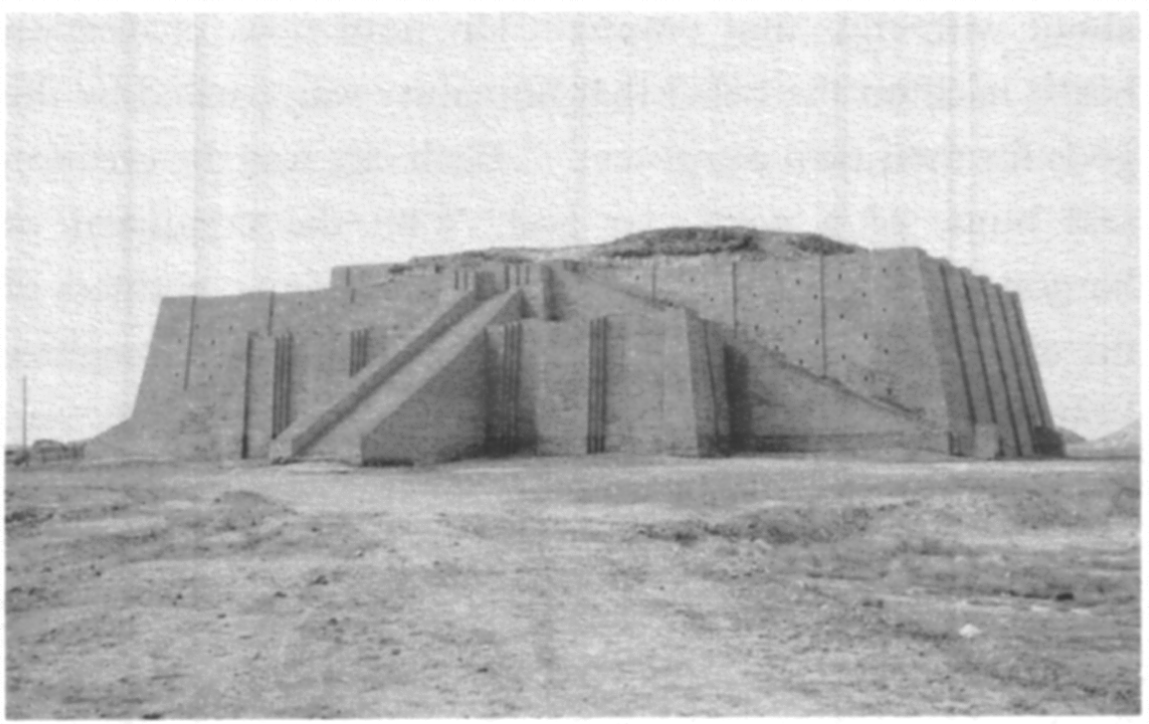

The Akkadians also built the first ziggurats: stepped asymmetrical flat-topped pyramidal structures with temples at their summit. The very word ziggurat is an anglicised form of the original Akkadian ‘ziqquratu’, and in time one of the greatest of these would be a 300-foot-high Babylonian ziggurat named Etemenanki. Although this huge structure is now reduced to nothing but rubble, its name translates as ‘home of the platform between heaven and earthy’, confirming that these were the edifices that gave rise to the legend of the Tower of Babel. Although no temples have yet been found at the summit of any extant ziggurats, we know of their existence.

The Ziggurat of Ur, which rises to 100 feet. Some such structures are known to have been three times this size.

Herodotus describes the furnishing of the shrine on top of the ziggurat at Babylon and says it contained a great golden couch, on which a woman spent the night alone. The god Marduk was also said to come and sleep in his shrine. Thus, the son of god was the issue of a god and a human woman, an early example of the story that would persist through Zeus in the Greek myths into the Christian era.

Speculations on the precise origins of the ziggurats are equally intriguing. Some claim that they represent a sacred mountain, a folk-memory from the original Sumerian homelands, which according to some sources was ‘the mountains of the north-east’. This suggests the Zagros Mountains, which occupy western Persia and border the Fertile Crescent. A similarly plausible suggestion, which in no way contradicts the mountain myth, claims these ziggurats were raised as protection for the temples against the seasonal floods, some of which could be extreme.

As their architecture grew, there is no doubt that they were intended to become increasingly awesome and forbidding to the common people gathered below. The complicated sets of staircases worked into their design would have made them easy to defend against intruders, at the same time preventing any secular spies from discovering the secrets of the temple ceremonies and initiation rituals. Once again, echoes of such practices have come down to us in the Eleusinian Mysteries of the Ancient Greeks, later ritual sacrifices of many kinds, and remnants can even be detected in the high altars of Christian churches.

Only priests were permitted to ascend to the top of ziggurats, and one of their duties was to observe the movements of the stars in the night heavens. Here astronomy was certainly entwined with astrology: yet the astronomical understanding of the movements of the planets developed by these priests would later enable the Babylonians accurately to predict eclipses of the sun many centuries into the future. These used advanced geometric techniques that would not be rediscovered in Europe until the fourteenth century AD.

Sequence

What originated with the Akkadians would be developed by the Babylonians, who gave the world further distinctive features of early civilisation and empire. Not least of these was the Code of Hammurabi, the world’s earliest comprehensive code of laws. This was inscribed in Akkadian on a seven-foot-high stele dating from around 1754 BC during the reign of the Babylonian king Hammurabi. It contains 282 laws, covering aspects of civil life ranging from slander to theft and divorce, as well as most famously the legal principle paraphrased as ‘an eye for an eye . . .’

Meanwhile some 700 miles or so to the west of Babylon, a parallel empire was developing in the form of Ancient Egypt. Here too a civilisation evolved its own similar, yet distinctive hallmarks, such as pyramids, the successive rule of pharaonic god-kings, and hieroglyphic writing, in this case on papyrus. The Egyptians also developed their own more down-to-earth, but equally impressive, form of mathematics. Each year the Nile flood would recede, leaving bare mudflats, which would have to be divided into plots of land precisely commensurate with those occupied prior to the rising flood. This led to a mathematics involving immensely complicated algebraic fractions (whereas the Babylonian mathematics had more of a tendency towards abstract geometric precision).

H.G. Wells, writing a century ago, would claim of these empires:

We know that life for prosperous and influential people in such cities as Babylon and the Egyptian Thebes, was already almost as refined and as luxurious as that of comfortable and prosperous people today.

This may well be, yet it is always worth bearing in mind P.J. O’Rourke’s advice: ‘When you are thinking of the good old days, think one word: Dentistry.’ Quite aside from this painful art, it is worth considering another significant dental fact. The teeth of Ancient Egyptian mummies (i.e. the fortunate few described above) are invariably flat. This was initially ascribed to evolutionary reasons. It is now known that they were ground down by the amount of desert sand and grit that could not be prevented from entering prepared food. And to dental hardships one could add life expectancy, virulent disfiguring diseases, the vice-like conformity required by such societies . . . sufficient imagination can always add to this list.

Such strictures will apply, in more or less a degree, to all empires great and small, before and after Ancient Egypt. It is the ethos that can be rosy, instructive, inspirational, and so forth – seldom the nitty-teeth-gritty facts. But this should not be a cause for pessimism. History scrutinises the past, and seeks to learn from it: it does not seek to live in it.

Egyptian influences would spread to Crete, with Babylonian influences dispersing through Anatolia and Persia, while the Phoenicians transported such ideas throughout the Mediterranean. Amongst the Greekspeaking city states that occupied the islands and coasts of the Aegean, this would produce a transformation. Uniquely, Ancient Greek civilisation was fragmented, while its learning was divorced from religion. Liberated from an oppressive all-embracing imperial and religious hierarchy, individualistic thought blossomed, giving birth to what we now see as Western civilisation.

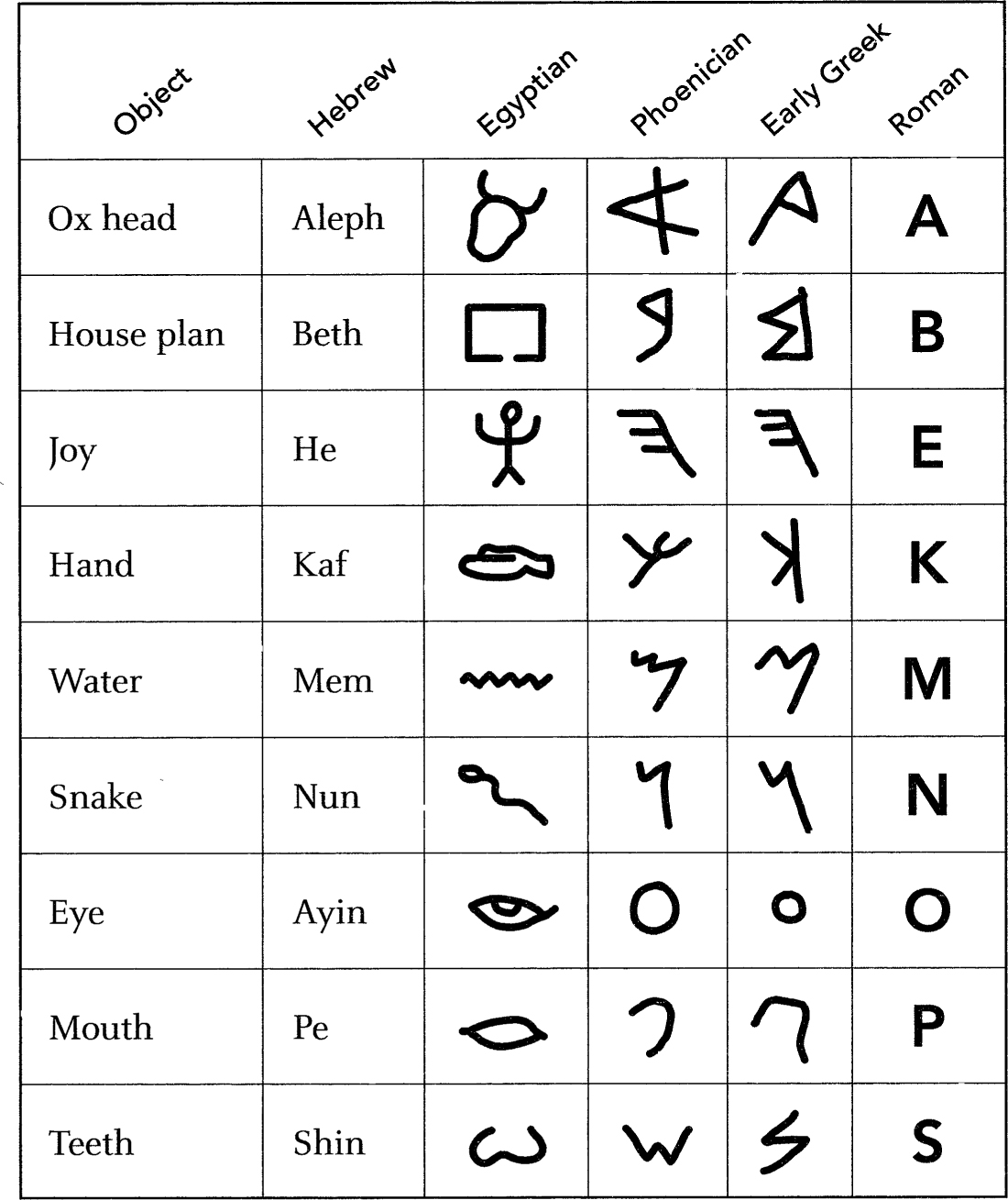

Examples of evolving alphabet

Philosophy, democracy, citizens’ rights, the perfection of realistic sculpture, architecture, science, tragedy, comedy even, the list goes on . . . such creative individual freedom (for all but women and slaves) would become a template for Western civilisation. Once this strain of mentality had become established, it would never quite be eliminated from Western human evolution. Over the following two and a half millennia, it would survive tyranny, state terror, empires, barbarism, and even centuries of intellectual stagnation. However, from the outset, this mental trait would prove ineffective in combatting sheer physical power. For all its glories, the Greek world would quickly succumb to the military might of the expanding Roman Empire.

Despite such radical developments, there was no clear-cut break with earlier empires. This is perhaps most significantly illustrated by an unmistakable thread of continuity in the evolution of alphabetical writing, which gradually replaced cuneiform scripts such as Akkadian and Babylonian.

1 Owing to silting and the Tigris-Euprates delta, the north-western coast of the Persian Gulf has now moved some 100

miles south-east of its location in ancient times.

2 In time, this became a ritual of Akkadian rulers, marking the successful end of a campaign or war.

3 In fact, Shelley based his poem upon the pharaoh Ramesses II, who would rule in Ancient Egypt a millennium or so later.

4 Spoken Ancient Hebrew fell into disuse around AD 300, remaining only in written Biblical and religious usage. It was revived in its modern form in the early twentieth century by the Russian-born scholar Eliezer Ben Yehuda, and became the official language of the state of Israel.

5 Mesopotamia is in fact the later Greek word for this region, meaning ‘the land between between two rivers’, i.e. the Tigris and the Euphrates.

6 Narâm-Sin’s stele can be seen at the Louvre in Paris.

7 To put this into context: such a period constitutes around half the length of the British Empire, and is the equivalent of the entire British Empire at its zenith.