Just as the Huns, the Goths and the Vandals had driven all before them some eight centuries previously, so would the Mongols prove an irresistible force as they spread out from their homeland across the Eurasian land mass.

In migrant tribes of hunter-gatherers, living off the land through which they passed, every man was a warrior. Such migrations could support roaming bands of a few hundred people at most. The next stage of human development involved shepherds. In such societies too, every man was a warrior; but as the warriors brought their sustenance with them in herds, they could move in larger groups. This was how Muhammad could gather 10,000 men for his march on Mecca.

The third stage of development involved settled pastoral people. Such societies were more sophisticated. The surplus of their produce could support leisure and culture – as well as a standing army. Yet ironically, these cultured societies were no match for the migrations of what were essentially barbarian tribesmen, as the Romans discovered. And now, almost a millennium later, the peoples of the Eastern and the Western worlds would be forced to learn this lesson anew – as the Mongol hordes poured out from their eastern fastness across two continents.15

No great empire is fundamentally unique – but the Mongol Empire would contain sufficient anomalies to set it apart from almost all other empires, both before and since, great and small. Its history, even its very existence, is beset with contradictions. This would be the largest contiguous land empire the world has ever seen, stretching from the Pacific to the eastern borders of Germany, yet it would prove the most short-lived great empire in history. It would be an empire that tolerated all religions – from Islam to Christianity and Buddhism, from Shamanism to Judaism and Taoism. Yet it would also forbid many of these religions from carrying out their most sacred practices.

For instance, followers of Islam were forbidden to slaughter meat in the halal manner; likewise, Jews were forbidden to eat kosher and practise circumcision. All citizens of the Mongol Empire had to follow ‘the Mongol method of eating’. Similarly, the Mongol edicts against polluting water, which precluded the washing of clothes, or even bodies, particularly during summer, hardly endeared them to religions that held a strong connection between purity and godliness, with an abhorrence of the unclean.

Other similar contradictions abounded. Despite the vast area of its conquests, the Mongol Empire would leave scattered ruins and no great buildings; the only magnificent monument that the Mongols caused to be created was the Great Wall of China, which had been intended to keep the Mongols out. This was an empire notorious for the vast slaughter it inflicted on its enemies; yet it would leave behind in Europe a legacy that caused an even greater death toll, in the form of the Black Death.

Even its emperors present us with a conundrum. Its first emperor, Genghis Khan, would go down in history as probably the most bloodthirsty conqueror of all time, an often genocidal invader who swept into oblivion those in his path. Yet the last ruler of the Mongol Empire is remembered in the romantic imagination of the West for his fabulous capital, Xanadu. This would be described by the contemporary English traveller, Samuel Purchas:

In Xanadu did Cublai Can build a stately Pallace, encompassing sixteen miles of plaine ground with a wall, wherein are fertile Meadowes, pleasant Springs, delightful Streames and all sorts of beasts of chase and game, and in the middest thereof a sumptuous house of pleasure which may be moved from place to place.16

Now all that remains of Xanadu are ruins circumscribed by a grassy mound where the city walls once stood. Yet Kublai Khan was to be no Ozymandias. In later life he would leave Xanadu and set up his capital in Khanbaliq (Mongolian: ‘The City of the Leader’) on the site of what is now the capital city of China: namely, Beijing. Many centuries have come and gone, yet this city and its great monuments have yet to lie in shattered remnants amidst the lone and level sands.

To the north of China, beyond the famously treacherous shifting singing sands of the Gobi desert, and hemmed in by mountains to the north and the west, lie the vast grassy steppes of the landlocked territory known as Mongolia. This plateau is around 5,000 feet above sea level, and stretches some 1,500 miles from east to west, and more than 500 miles from north to south. It has been occupied by nomadic tribesmen since time immemorial. (Historians estimate this as being since around 2000 BC.) The origin myths of these people were entirely vocal, and over the centuries they have become muddled with Buddhist and Shamanistic folklore from surrounding peoples. But one thing remained certain, these tribal nomads regarded the wolf as their legendary ancestor, and they strove to emulate his qualities: cunning, ferocity and the strength of the pack.17

The Mongols may have identified themselves with the wolf, but the one animal these tribesmen cherished above all others was the horse. Mongolian horses were (and remain to this day) a sturdy, stocky breed of amazing endurance. Wandering free, they subsist on grass alone, and are able to withstand the extremes of temperature that characterise this otherwise empty region. In summer, the heat rises to over 30°C, in winter it falls to – -40°C.

The nomadic Mongol tribes developed an intense and symbiotic relationship with their herds of horses, which provided them with their every need. Horse meat was food, the long tails and manes of these animals could be woven into ropes, their skin could be used to reinforce the felt of the tent-like ger against the piercing cold wind, their dung provided fuel. And their mares provided milk. Boiled and dried into chunks, this could be stored and carried. Fermented it provided acidic-tasting alcoholic kumis. Productive mares could be milked up to six times a day. And in times of extremity, especially when engaged in warfare, the tribesmen learned to slit a vein in their horse’s neck, providing a small cup of blood, which would keep them alive.

Though the horses roamed free, they were trained to respond to their master’s call, or whistle, like dogs. When the tribesmen were pursuing an enemy, they would bring along anything up to half a dozen horses each, so that they always had a fresh mount. Although the horses only weighed around 500 lbs, they could carry loads well in excess of their bodyweight. When ridden, they could gallop over six miles without a break. In the frigid cold of a winter’s night, a Mongol would snuggle up against his horse for warmth. When they reached water, the rider would kneel down beside his mount to drink. Yet although a Mongol tribesman could always distinguish each of his collection of horses by its skin markings, he never gave them names. It was almost as if his horses were part of him, and needed no alien designation.

As the population on the steppe multiplied, the various Mongol tribes began to fight over territory. These tough, warlike people, with their pony-sized steeds, soon became fearsome warriors. The saddles on which they rode had short stirrups, so that the rider could guide his horse with his legs, enabling him to use his arms to fire lethal metal-tipped arrows from his short bow with great accuracy. Tied to the saddle behind him was an array of weapons, which might include a scimitar, daggers, and a mace or a hatchet, as well as a leather bottle of milk. For armour, he wore cured horse-skin studded with metal.

Over the centuries a body of strict rules grew up concerning the treatment of horses, and woe betide any who broke them. This was exemplified in Genghis Khan’s order: ‘Seize and beat any man who breaks them . . . Any man . . . who ignores this decree, cut off his head where he stands.’

The man we know as Genghis Khan was born in a remote north-east corner of the Mongolian plateau, where the Siberian winds blow in from the mountains to the north. According to a local legend, seemingly undiluted by later folklore, these Mongols originated from the forests on the slopes of the mountains when the Blue-Grey Wolf mated with the Beautiful Red Doe, who gave birth by the shore of a large lake to the first of the Mongols, Bataciqan. The large lake is assumed to be Lake Baikal, in modern-day Russia. Some time after this, Bataciqan’s descendants left the forests for the steppe, where they settled along the Onon River.

The Mongols saw themselves as different from the neighbouring Tartar and Turkic tribesmen, claiming descent through the ancient Huns, who founded their first empire in the region during the third century. (Hun is the Mongolian for ‘human being’.) It was these Huns who in the fourth and fifth centuries migrated west across Asia and into Europe, where they dispersed the Germanic tribes, the Vandals and the Goths, causing the movement of peoples that brought down the Roman Empire and ushered in the so-called Dark Ages.

Life on the steppe was hard for the Mongols. The chill Siberian winds brought intermittent rainfall. This froze on the mountainside in winter, melting in summer to flow down into blue lakes which spilled into rivers, bringing water to the vast parched grasslands that stretched to the empty horizon. Sometimes there would be no rainfall for years on end, with the sky remaining like a vast blue dome over the landscape. The endless blue sky, which spread from horizon to horizon in all directions, was worshipped as the One True God by these people. It was He who brought the clouds bearing rain.

Modern climatologists have discovered that some time after the birth of Genghis Khan, climate change began to moderate the weather of the region for several decades. This brought warmer temperatures and more rainfall. As a result, there was a widespread increase in grass. Herds of horses and other livestock were able to multiply, as did the tribesmen. The inevitable result was increasing tension between the nomadic tribesmen over large expanses of coveted land with no natural barriers. Without warning, tribesmen attacked the isolated ger of rival tribes, carrying off young women and boys into slavery. Outnumbered, the menfolk fled, carrying off their finest horses and wives in order to warn their allies, so that they could return to fight another day. Revenge was a constant driving force.

Into this world in 1162 was born a child named Temujin (who would only later assume the name Genghis Khan). Temujin was the son of Yesugei, a leader of the important Borjigin clan, which lived close to the site of modern Ulaanbaatar. Temujin’s early life was hard and brutal. When he was just nine, his father was poisoned, and his tribe cast out his mother Hoelun and all the family children. The oldest of these was Bekter, who was not directly related to any of them, being a son from Hoelun’s murdered husband’s previous marriage. Forced to scavenge for a living on the barren steppe, the close-knit family group hunted and foraged to stay alive, catching fish in the Onon River before it froze over for the winter.

An intense rivalry grew up between Bekter and Temujin, which came to a head when Temujin learned that Bektar intended to take Hoelun as his wife. Whereupon, Temujin stalked Bekter and slew him with an arrow. Bektar’s last words to his brother are said to have been: ‘Now you have no companion other than your shadow.’ As far as can be gathered, Temujin was probably not yet even a teenager.

At this point it is worth pausing to examine how we have come to know these events in such detail. The story of Genghis Khan’s life is recorded at some length in The Secret History of the Mongols, the bible of the Mongol people. This was written in the vertical lines of original Mongol script by an anonymous scribe some years after Temujin’s death. The Secret History of the Mongols remained unknown to the West until a Chinese version was discovered by the nineteenth-century Russian monk, Pyotor Kafarov, during his travels in China. However, a faithful translation from the reconstructed Mongol text would not be made until as late as 1941 by the German sinologist, Erich Haenisch.

The work’s flavour is biblical, and the accuracy of its text is of a similar order. In other words, it remains sacred to its people; yet apart from its mythological opening, it would seem to be a quasi-accurate narrative, this being confirmed by contemporary hearsay accounts passed down in stories.

The ancient Mongol language would remain purely verbal until Genghis Khan ordered the adoption of the script used by the Uighur Turks. These were the occupants of the large Xinjiang region of north-west China, which lies to the west of modern Mongolia, separated by the Gobi Desert. In the original Uighur script, and its Mongol variant, the letters of each word are written from top to bottom, i.e. vertically, in lines of words. These complete lines are then read in sequence from left to right.

The anonymous author of The Secret History of the Mongols indicates that it was finished in ‘The Year of the Mouse’. The Mongols copied the Chinese calendar, which is based on a twelve-year cycle, with each year named after a different animal. Scholars scrutinising the events mentioned in the text have come to the conclusion that The Secret History was written in 1228, 1240 or perhaps even 1252.

We can now return to the adolescent fratricide, Temujin. When he arrived back at the family encampment, he encountered his mother Hoelun. With a mother’s acumen, she realised at once what he had done. Immediately she flew into a rage, screaming at her son the very same words that the dying Bektar had uttered to him: ‘Now you have no companion other than your shadow.’ The psychology bred in Temujin by the simplicity and savagery of this almost primeval world can barely be imagined. Europe may have been a thousand miles distant, but it might as well have been a thousand years away.

On the other side of the world. Western civilisation had begun to stir once more, with a mature medieval culture beginning to emerge. Great gothic cathedrals were being built at Reims and Chartres, universities were already well established at places such as Oxford, Bologna and Paris. Meanwhile in the Arab Empire, amidst great cities such as Baghdad and Cordoba, the mosques and bazaars were thronged with populations numbering in the hundreds of thousands. And to the south of Mongolia, in nearby China, behind the protection of the Great Wall, the Jin dynasty under the Emperor Shizong was entering a period of peace and prosperity. This was a time of scholars and poets, wood blocks printing the texts of Confucius, and artists painting the birds and landscapes of the Chinese countryside.

Meanwhile in 1177, when Temujin was fifteen, he was taken captive by marauding tribesmen, who led him off to slavery in a cangue. This consisted of two large, heavy flat pieces of wood, carved so that they could be clapped closed around the prisoner’s neck; the weight of the wood was a painful burden, and its size meant the prisoner was unable to feed himself with his hands, leaving him utterly dependent on his master. Miraculously, Temujin managed to persuade one of the tribesmen to help him escape. During this, and his consequent adventures, Temujin appears to have exhibited a winning charisma, inducing people to help him, and then to join up with him.

Prior to the death of Temujin’s father, he had arranged for his son to be betrothed to a girl called Börte, in order to form an alliance with another powerful Mongol clan. Temujin now travelled to the Onggirat tribe to claim his bride. No sooner had he married Börte than she was kidnapped by neighbouring tribesmen. Temujin immediately led a campaign to avenge this crime, and soon retook his wife. Tales of Temujin’s escape from slavery, and his bold rescue of Börte, earned him a high reputation for bravery and leadership. He soon rose up the tribal hierarchy, becoming a tribal chief.

By means of tactical alliances and tribal warfare, Temujin eventually established himself as leader of all the Mongol tribes. By 1206 he had become ruler of all the neighbouring tribes, including the Turkic Tatars and Uighurs. A gathering of the tribes – a khuriltai – was held, and Temujin was acknowledged as ‘Genghis Khan’ (‘leader of all the people living in felt tents’). This unprepossessing title would soon strike fear into the hearts of all who heard it.

Genghis Khan was now undisputed ruler of the entire plateau ‘from the Gobi [desert] in the south to the Arctic tundra in the north, from the Manchurian forests in the east to the Altai Mountains of the west’. Realising that this Mongol alliance would soon fall apart if it was not united and put to some use, in 1209 Genghis Khan launched a series of raids into nearby foreign territories. In 1211, spurred on by the sheer exultation of victory, Genghis Khan and his burgeoning army of horsemen rode south into northern China. The success of his furious but disciplined primitive army was beyond belief. Within the next few years, Genghis Khan had overthrown the Jin Dynasty. As he later explained: Heaven had grown weary of the excessive pride and luxury of the Chinese.

I am from the barbaric north. I wear the same clothing and eat the same food as the cow-herds and horse-herders. We make the same sacrifice and share the same riches. I look upon the nation as a newborn child and I care for my soldiers as if they were my sons.

Prior to this, Genghis Khan went on, he had merely been interested in plunder. But now he had ridden south and succeeded in something that no one else had ever achieved in history. He had defeated the Chinese. And from them his army had learned how to use siege engines, catapults and even gunpowder. Genghis Khan now turned his eyes to the west and prepared to launch an attack upon kingdoms and empires, with long histories and fabled cities the like of which neither he nor his men had even dreamt existed. From now on, he vowed, he would unite the whole world in one empire.

Which brings us to the question of sideways history. Normally history is conceived as running in a linear trajectory. This may be seen as a vertical time-line on a graph. Sideways history may be seen as a horizontal line, taking account of various stages of history running in parallel. This is best illustrated by the twentieth-century economist, Milton Friedman, who observed that when he was living in San Francisco, he found himself living amidst almost the entire history of economics in its various stages of development. Around him he saw a great variety of immigrant communities and different classes: Chinatown, the Italian district, and many other social groups, each making use of their own cultural form of economic life. There was barter economy, credit economy, deferred debt economy, capital economy, and even the simple quasi-socialist communal economy practised by religious communities. Economics, in all its history, was alive and thriving around him.

Much the same can be said of the empires and countries occupying the Eurasian landmass in the early thirteenth century. In the east there was the highly stratified Chinese Empire. From the Near East to Spain was the Abbasid Caliphate, an essentially religious society, which still tolerated a degree of secular thinking in the form of science and philosophy. In Russia and Eastern Europe, tyrannies of primitive serfdom flourished. Meanwhile in Western Europe a variety of social administrations had sprung up. These ranged from democracy (Florence) to absolute monarchy (France), along with oligarchy (Venice); whilst in England there was a kingdom on the verge of the Magna Carta, which would grant citizens inalienable rights.

Almost all of these societies were evolving – more or less slowly – as they sought to absorb the political, social, economic and scientific advances that were stirring into life. Progress and survival would soon be the order of the day. All this begs a number of basic questions. What precisely is social progress? Who should benefit from it? And what is its aim? Indeed, does it even have an ultimate end: a utopia? These difficult questions remain without a final answer to this day, when it appears that liberal social democracy and economic advance are far from being the inevitable course of future civilisation.

Such questions will begin to arise of their own accord as we examine the empires that come into being in more progressive times. And as we shall see, any attempt to find even a provisional answer to them is not easy. Such questions continue to nag at our empire-building impulse.

However, it would seem that one thing can be stated for certain: the spread of the Mongol Empire across Eurasia did not result in what anyone would see as progress. Or did it? History moves in mysterious ways, its blunders to perform. Despite the massive destruction involved in the Mongol invasion, some have seen this ‘clearing of the ground’ as a necessary prelude, sweeping away the social, political and cultural rigidities, which prepared the way for the more adaptable, more progressive civilisation to come. But first we must see what this freeing up of history involved.

In 1211 the Mongol invasion, led by Genghis Khan, swept westwards like fire burning through a map, and with similar results. They rode for thousands of miles through southern Siberia, across the Turkic lands, and then on to the Khwarazmian Empire. This empire of five million people occupied greater Persia and western Afghanistan, as far north as the Aral Sea. Its territory included historic cities such as Samarkand and Bukhara, which had grown rich from the Silk Route trade between China and Europe. Yet this large and sophisticated empire fell within two years to Genghis Khan’s army.

How on earth did Genghis Khan and his army of primitive horsemen achieve all this, and with such speed? There was no doubting the efficiency and ferocity of his fighting men, organised in tumen – units of 10,000 men galloping behind their black horsehair tug banner. But how did Genghis Khan manage to instil discipline amongst such fiercely independent horsemen? How did he make them follow his pre-arranged tactics and commands?

The life of the Chinese military theoretician Sun Tzu, who wrote The Art of War around 500 BC, offers a clue here. Sun Tzu was ordered to appear before his leader, who had read his book and wished to test its author’s theory on how to manage soldiers. Could it even be applied to women, for instance? Of course, replied Sun Tzu. Whereupon he divided the leader’s 180 concubines into two companies, each armed with spears, selecting a leader for each company. He then attempted to drill the two groups, passing on orders to their leaders. But all of the young women simply burst out laughing.

Sun Tzu explained to his leader: ‘If words of command are not clear and thoroughly understood, then the general is to blame.’ He ordered the leader of each group to be beheaded, replacing them with a different leader. When the next orders were given to the leaders and passed on to the two groups, both groups carried out their orders with alacrity and great efficiency. Although Genghis Khan certainly never read Sun Tzu, his method of instilling discipline amongst his men was remarkably similar.18

As for the rest, Genghis Khan knew the speed, endurance and ruthlessness of his horsemen, and employed his lightning tactics accordingly. A typical move was for him to use heavy firepower to blast a passage through the enemy lines for his cavalry units, which were then deployed with maximum efficiency, piercing the enemy line and then fanning out behind their rear, cutting their supply lines and instilling panic, which caused the enemy to flee in all directions. Communication between separate units was maintained by the use of flags. Indeed, it is to the Mongols that we owe the art of semaphore.

The lasting effect of these tactics can be seen in the fact that the German Second World War Panzer General, Heinz Guderian, the master of Blitzkrieg, identified the inspiration of his tactics as Genghis Khan. Though the ruthlessness with which Genghis Khan followed through on his tactics is another matter. According to Khan’s biographer Jack Weatherford: ‘The objective of such tactics was simple and always the same: to frighten the enemy into surrendering before an actual battle began.’ Any who then resisted could expect the very worst. After taking Samarkand, Genghis Khan ordered the entire population to be assembled in the plain outside the city walls. Here they were systematically butchered, their severed heads arranged in pyramids.

In Bukhara, as his Mongol soldiers burnt the city to the ground, Genghis Khan addressed the wailing remnant population in the main mosque, announcing that he was the ‘flail of God’ sent to punish them for their sins. When the Khan’s Mongol army took Gurganj, the capital of the Khwarazmian Empire, the thirteenth-century Persian scholar, Juvayni, recorded that Genghis Khan’s 50,000 Mongol soldiers were commanded by their leader to kill twenty-four citizens each. As there were not enough citizens to meet this command, and the soldiers well understood the punishment for not fulfilling their leader’s orders to the letter, the ensuing swift and competitive slaughter of several hundred thousand people resulted in what has been called ‘the bloodiest massacre in human history’.

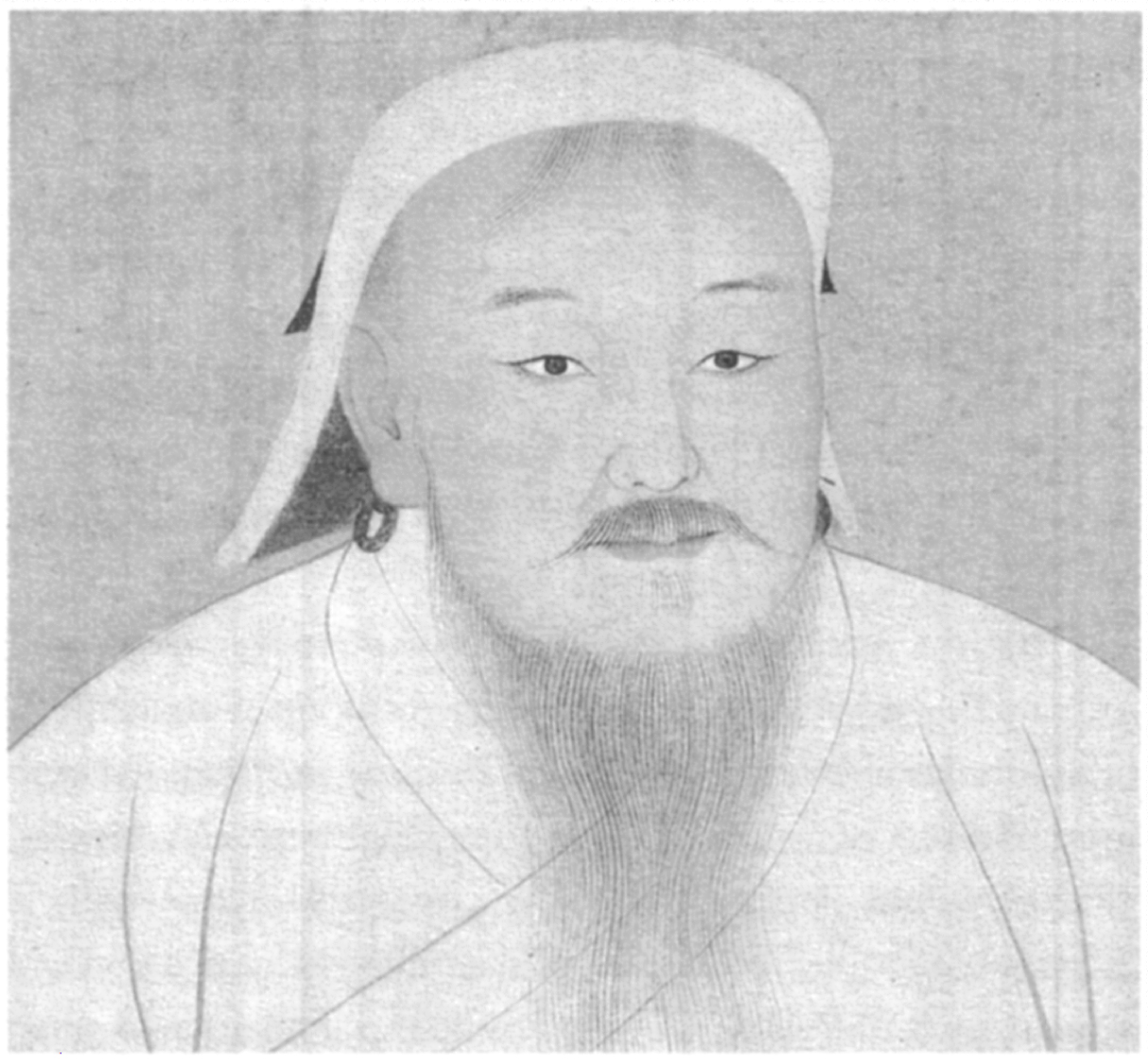

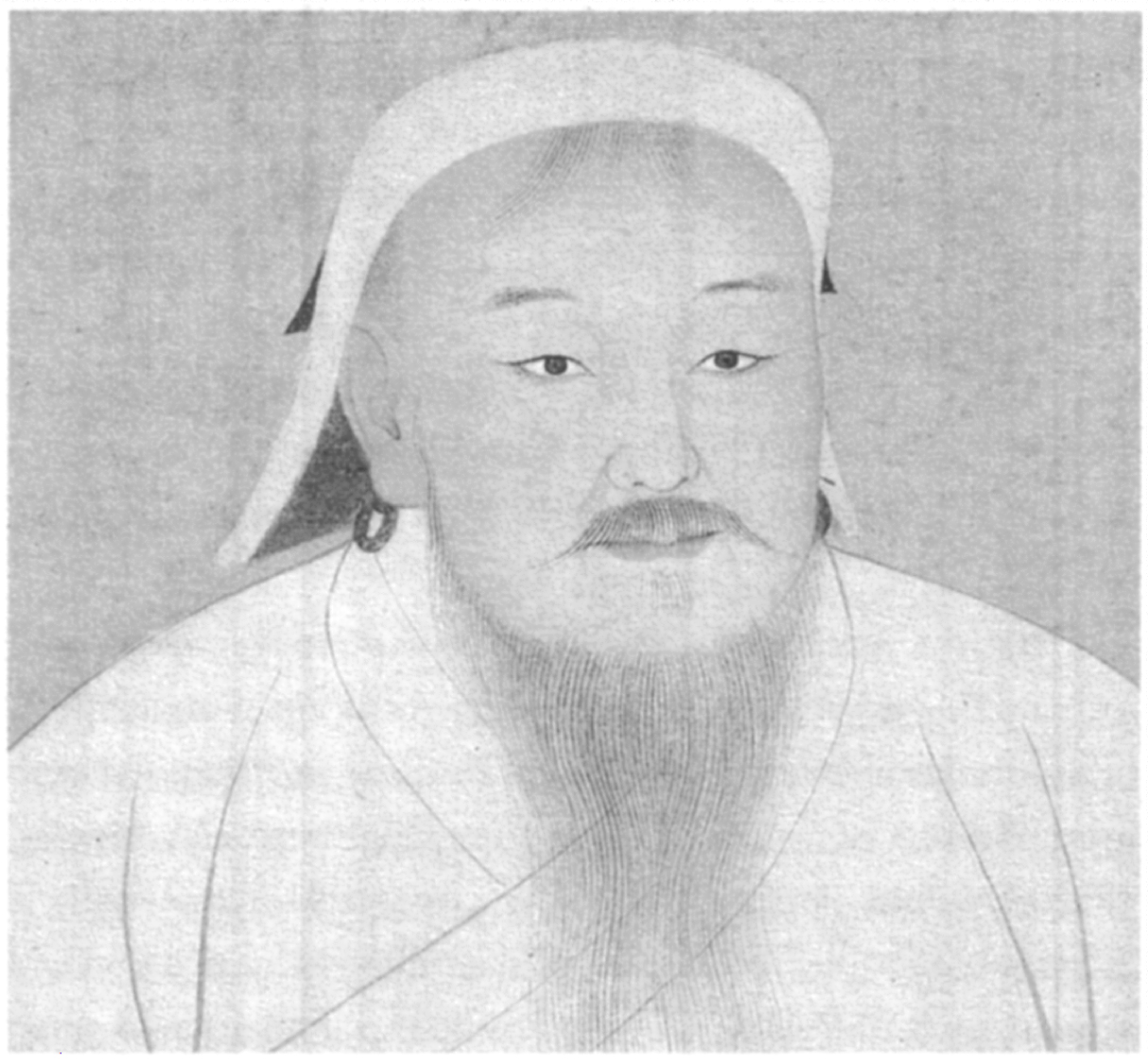

An enigmatic, somewhat bland portrait of Genghis Khan in his later years conveys little of the sheer terror his presence could inspire. It was drawn around forty-five years after his death, but the artist consulted with men who had known Genghis Khan closely during his lifetime. Originally black and white, it was softened by colour during the following century.

Genghis Khan.

Genghis Khan now returned to Mongolia, but despatched two of his most trusted generals, Chepe and Subutai, north with 20,000 horsemen. This army swept up through the Caucasus and into Russia. Here they were confronted by an army of 80,000 men, which they annihilated. Instead of occupying this territory, they then withdrew: Genghis Khan had ordered that this was to be merely a ‘reconnaissance mission’.

Such exemplary slaughter brings us to the deeper problem of morality, and questions concerning the ethics of conquest and empire. Indeed, is there any such thing as morality involved in the imperial enterprise? The usual justification for such conquest is the spreading of progressive civilisation. Beneath this lie even more fundamental questions concerning the ethics of empire, and the morality of progressive civilisation itself. Is there such a thing as either? And if so, why should we regard such things as universal? Are all human beings equal? Should they all be treated in the same fashion? Should they all be subjected to the same universal laws? If so, what is the ultimate moral law?

Over the centuries, and over its extensive reach and influence, the Western tradition has come up with surprisingly similar answers. The biblical Book of Leviticus, written around 1400 BC, stated: ‘Love your neighbour as yourself.’ (Freud would declare this: ‘The commandment which is impossible to fulfil.’) Despite this, similar injunctions would appear in Buddhism, Taoism, Hinduism, and indeed most of the world’s major religions. One and a half millennia after Leviticus, Jesus Christ would exhort his followers: ‘Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.’ Six centuries later, Muhammad would pronounce: ‘As you would have people do to you, do to them.’

Over a millennium after this, Europe’s leading philosopher, Emmanuel Kant, would recognise that such an injunction did not necessarily involve a belief in God. Yet his analysis of ethics led him to a remarkably similar conclusion to all those previous theisms, when he declared the fundamental principle of morality to be: ‘Treat others as you would wish to be treated.’ It would take another 300 years before modern thinkers recognised that such a sentiment was inadequate. As Freud understood, it is psychologically impossible to maintain such a stance on a permanent basis. This was simply not how we actually lived or behaved in a social setting: our moral thinking did not work like this.

The Lebanese-American thinker, Nassim Taleb, has transmogrified this basic principle of morality into a maxim that more closely reflects our moral needs, ethical thinking and behaviour: ‘Do not to others what you don’t want them to do to you.’ The inapposite double negative may make it less easily comprehensible. (Is it simply a sleight of hand reversal, or turning inside out, of the Leviticus-Christ-Kant maxim? Examine it carefully: it is not.)19 This would seem closer to a basic instruction for the guidance of our actual moral behaviour. Not so much love thy neighbour, as proceed with due care . . .

It is not difficult to see Genghis Khan adhering to this maxim. For a boy whose father had been murdered, whose step-brother had plotted to marry his mother, and who had been taken into slavery, enduring the pain and humiliation of the cangue, he can have been under few illusions about what others wanted to do to him. And he had certainly chosen to act accordingly, pyramids of skulls and all. In fact, the question of morality and empire remains open, leaving us with little but clichés. Might is right; history is written by the victors; and so forth. Only the hindsight of historians begins to add any perspective to such views. But this comes later. Where empires are concerned, the certainty of the present often prevails with much the same conviction as that held by Genghis Khan.

Genghis Khan would die at the age of sixty-five in 1227, ironically from injuries sustained from falling off his horse while crossing the Gobi Desert. Genghis Khan’s grave has yet to be found. According to legend, a river was diverted over his burial place, so that it would never be discovered. Such a ritual harks back to the beginnings of historical time: both Gilgamesh and Attila the Hun are said to have been buried in the same way.

Even before Genghis Khan’s deaths a khuriltai had been called to decide who amongst his sons should be his successor. This had broken up in acrimony. Following his death, the empsire was divided into several khanates governed by his sons. However, his third son, Ögedei, would eventually be recognised as the second ‘Great Khan’ of the Mongol Empire.

Ögedei was renowned for his love of alcohol, and on his installation as Khan he became so drunk that he ‘threw open his father’s treasury and riotously distributed all the riches stored there’.

Despite such an inauspicious start, Ögedei would prove a more than competent ruler. He was not inclined to lead the Mongol armies on campaigns and preferred to remain in his capital Karakorum, overseeing the campaigns and organising the administration. The gathering of taxes throughout the empire was modelled on the Chinese system, with the monies being collected by local ‘tax farmers’. Likewise, paper money was circulated, backed by silver. (At the time, paper itself remained a novelty in Europe, let alone paper money.)

The problem of communications throughout the vast empire had already been solved by Genghis Khan, who instituted a network of relay stations. As the Mongol army moved at speed, its communications system had to be even faster. Messengers riding on relays of horses could cover more than 150 miles a day over almost any terrain. (Such speeds and efficiency would not be matched for over 600 years, until the advent of the Trans-American Pony Express.)

Although Ögedei did not lead his men into battle, the empire continued to expand under his reign, pushing far into Europe. In 1241, the Mongols won the Battle of Legnica in Poland, and western Europe lay at their feet. News then spread throughout the empire of Ögedei’s death, and the commanders rode back as fast as they could to take part in the khuriltai to elect a new leader. By such chance was Europe saved from a Mongol invasion.

An uncannily similar situation would arise in 1258, after the Mongols had overrun the Abbasid capital, Baghdad. Egypt and the remnants of the entire Abbasid Empire lay at their feet. Then news came through that the fourth Great Khan, Möngke Khan, had died, and the leaders once more galloped off east for the khuriltai, leaving behind an ill-organised Mongol army. In 1260 this was defeated in Palestine by the Mamlukes at the Battle of Ain Jalut. Egypt, North Africa and Al-Andalus were spared the Mongol onslaught.

In that same year, Kublai Khan became the fifth Great Khan of the Mongol Empire. During his reign, the empire definitively split into four separate khanates. Instead of attempting to reunite the empire, Kublai Khan turned his attentions south to China, moving his capital to Khanbaliq (Beijing), with the intention of forming an entirely new empire.

Sequence

The three khanates to the west of Kublai Khan’s realm were the Golden Horde (occupying the territory north of the Black Sea and the Caspian, extending north and east into what is now Russia and Kazakhstan), the Chagatai Khanate (Afghanistan and north-east central Asia south of the Golden Horde), and the Ilkhanate (Greater Persia and west into Anatolia). All of these would convert to Islam (hence Il-Khanate), while Kublai Khan’s realm adopted Buddhism. The Golden Horde would eventually give way to Russia, but not before it had dealt a blow which turned the course of European history.

In 1348, Mongols of the Golden Horde were besieging the Crimean city of Kaffa (modern Feodosia), which was then a Black Sea trading port of the Genoese. When there was an outbreak of bubonic plague in the Mongol army, they catapulted plague-ridden corpses over the walls. (Some claim this as the earliest example of germ warfare.) Consequently, ships sailing from Kaffa to Europe transported the plague to Italy. Within half a dozen years, the Black Death (as it came to be known) had spread across Europe from Lisbon to Novgorod, from Sicily to Norway, in the process killing between 30 to 60 per cent of the entire population, probably accounting for over 100 million deaths.

A proto-Renaissance of European culture, inspired by a variety of disparate sources such as the Sicilian court of Frederick the Great (‘Stupor Mundi’), scientific and philosophical ideas imported from the Muslim world, and the new naturalistic painting of the Italian Giotto, was halted in its tracks, delaying the actual Italian Renaissance by a century.

15 The eighteenth-century Scottish philosopher and pioneer of economics, Adam Smith, suggested that had the Native Americans reached the stage of becoming herdsmen, they would probably have succeeded in driving the first pastoral European settlers from their shores.

16 Reminiscent of the Mongolian nomadic life, where tribespeople inhabited a moveable ger (a felt or skin tent, like a yurt).

17 The recurrence of the wolf in fundamental mythologies is widespread, if not universal. It stretches from Gilgamesh and Akkadian myth to Rome, from Norse mythology to Beowolf, even into New World Inuit and Cherokee legends. Some point to the wolf being the most feared predator faced by early humans; however, the underlying identification with wolves would seem to indicate some deeper psychological atavism.

18 Such ruthlessness is not confined to the distant past. The twentieth-century Soviet leader Joseph Stalin, no more an aficionado of military self-help manuals than Genghis Khan, adopted an uncannily similar policy to that recommended by Sun Tzu. During his 1930s Great Purge and indeed well into the Second World War, Stalin ordered the execution of literally hundreds of his military leaders (over 80 per cent of his commanders in the majority of sectors were purged), with a similar salutary effect on their successors and the men they commanded.

19 Muhammad himself declared in the Hadith: ‘What you dislike to be done to you, don’t do to them.’ However, in the ensuing century of the Muslim conquest, this evidently fell into abeyance.