At the turn of the fifteenth century, China was by some degree the most advanced civilisation on earth. This was the land, tales of whose wonders Marco Polo had earlier brought back to Europe. In 1405, Zhu Di, third emperor of the Ming Dynasty, ordered Admiral Zheng He to set sail from China with his fleet to explore ‘the oceans of the world’.

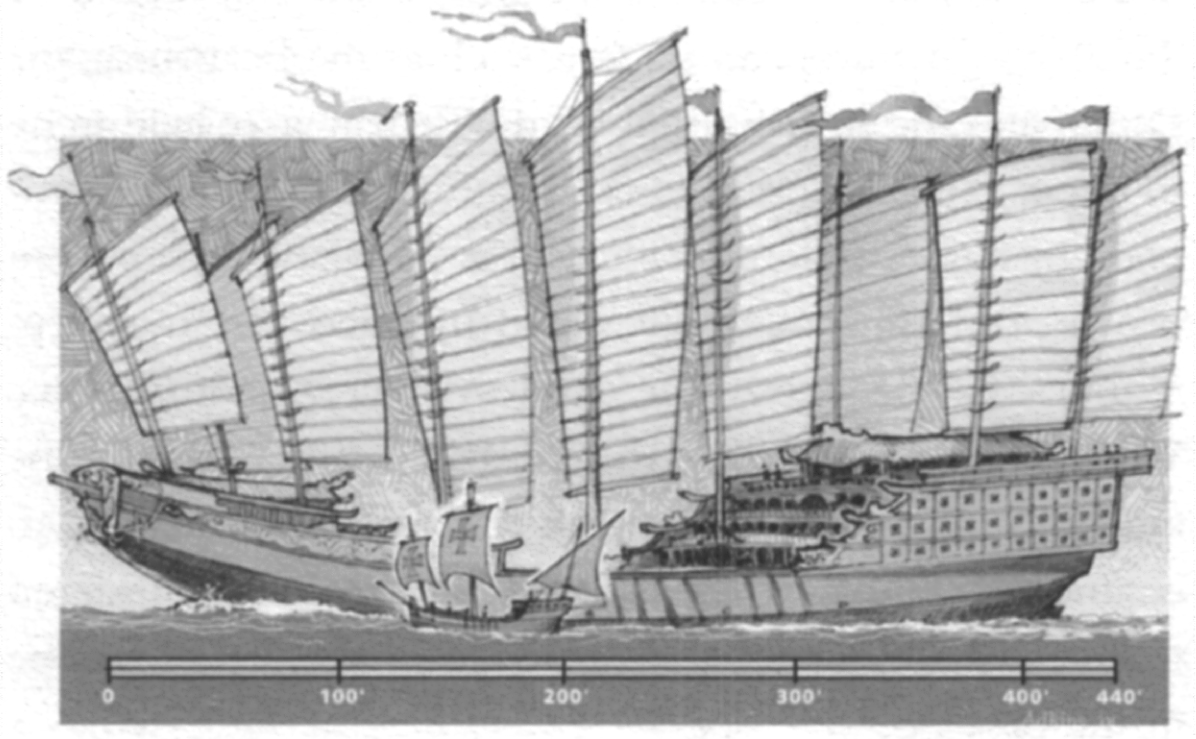

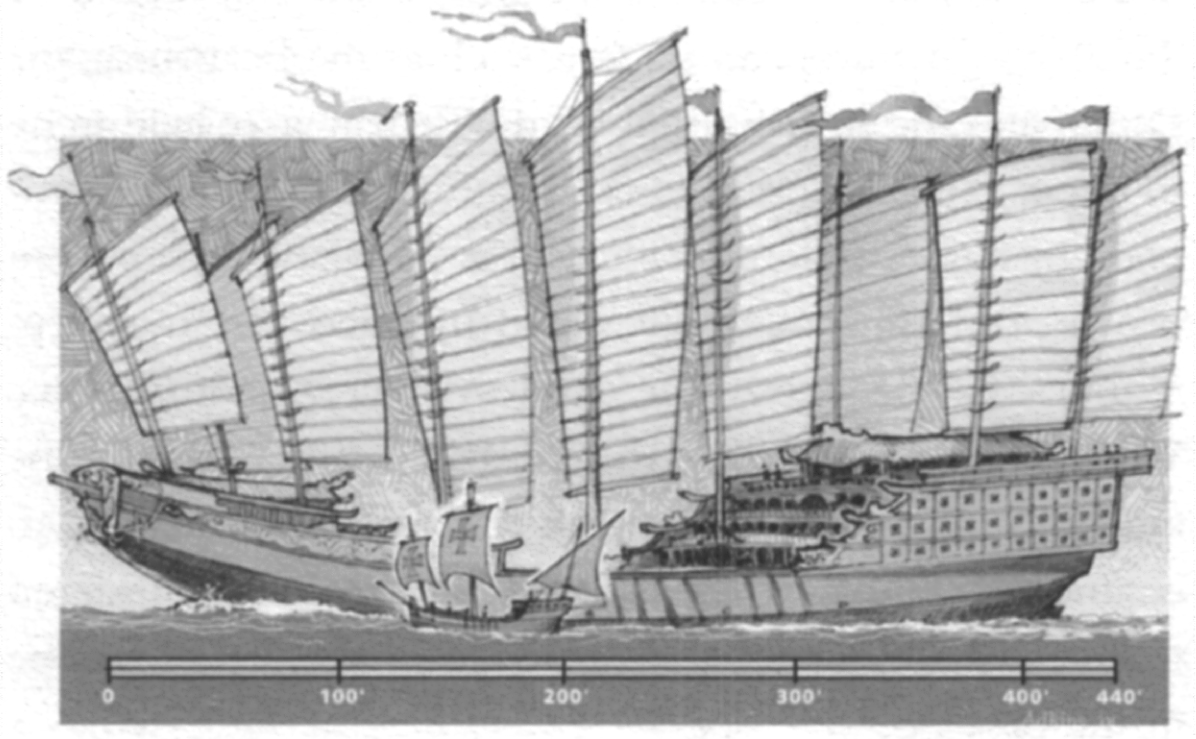

Admiral Zheng He had been in the service of the Emperor Zhu Di since he had been captured as an adolescent, and castrated according to contemporary custom. Zheng He had consequently risen through the ranks to become a man of mighty stature, both politically and physically. Eye-witness reports describe him as being almost seven feet tall and nearly five feet in girth. The fleet he commanded was of even more impressive proportions. It contained over three hundred large ocean-going, wooden-sailed junks manned by more than 28,000 men. The admiral’s treasure ship, a replica of which can be seen in Nanjing today, was 450 feet long. No comparable fleet would put to sea for over four centuries, until the First World War.

Zheng He and his fleet undertook six voyages between 1405 and 1424, during the course of which he travelled from Vietnam to Indonesia, from Burma, India and Ceylon to the Persian Gulf and up the Red Sea to Jeddah, then around the Horn of Africa down as far south as Kenya. Precise records of these six voyages are no longer extant, but it seems likely that in the course of his travels, Zheng He must have covered a distance equivalent to circumnavigating the globe twice over. Amongst the many wonders that he transported back to China was a giraffe from Somalia. Its arrival in China caused a sensation, confirming the existence of the legendary Chinese qilin, which in the sixth century BC had foretold the arrival of ‘a king without a throne’: later taken to be the philosopher Confucius, whose ideas would guide China through two millennia.

In 1430, when Zheng He was in his sixtieth year, he was ordered to undertake a seventh voyage and ‘to proceed all the way to the end of the earth’. This voyage would take three years, extend far into legend, and be a voyage from which he would never return. According to the controversial claims of naval historian Gavin Menzies, this voyage took Zheng He around the Cape of Good Hope to West Africa, from whence he crossed the Atlantic to America and rounded Cape Horn, sailing as far north as California. One admiral, who separated from Zheng He’s main fleet, is said to have reached Greenland and returned to China by way of northern Siberia (a passage that is likely to have remained open due to the after-effects of the Medieval Warm Period). Another admiral is said to have sailed as far as Australia, New Zealand and the first drift ice of Antarctica.

Evidence for Gavin Menzies’ claims are, according to Harvard historian Niall Ferguson, ‘at best circumstantial and at worst non-existent’. Despite this, tantalising anomalies appear to remain in the form of Chinese DNA discovered amongst Venezuelan native tribes, ‘a number of medieval Chinese anchors . . . found off the California coast’, as well as some surprisingly prescient coastal features that appeared on maps drawn prior to information received from fifteenth-century European explorers. Confirmation that Menzies’ amazing claims concerning Zheng He’s legendary seventh expedition were taken seriously in some quarters emerged when the Chinese president Hu Jintao addressed the Australian parliament in 2003, and asserted that ‘the Chinese . . . had discovered Australia three centuries before Captain Cook.’This has now seemingly become official Chinese history.

A modern representation of Admiral Zheng He’s treasure ship, alongside the vessel in which Columbus sailed the Atlantic.

In the years following Admiral Zheng He’s death in India in 1433, new Confucian ministers had risen to power at court, who ‘were hostile to commerce and . . . to all things foreign.’ A series of Imperial Haijin Decrees (Sea Bans) were issued, forbidding Chinese ships from sailing to foreign nations. Official records of Zheng He’s voyages were destroyed, and the imperial fleet was confined to port, where it soon fell into disrepair. These decrees were initially proclaimed as a measure against Japanese pirates, but had the unintended consequence of isolating China from the outside world. The progressive outgoing Ming civilisation began to ossify, and ‘one of the greatest eras of orderly government and social stability in human history’ fell into decline.

Our second telling tale concerning the ethos and legacy of empire happens to take place some three centuries later, just as Chinese isolation was beginning to be disturbed by the arrival of European traders, such as the Portugese, the Dutch and the British. By now, the British were beginning to impose their colonial administration on India. An exemplary instance of this took place in 1770, when the northern province of Bihar was devastated by one of its recurrent famines. Consequently, the de facto ruler of British India, Warren Hastings, ordered the construction of what became known as the Granary of Patna. Captain John Garstin, an engineer in the East India Company Army, was ordered to erect a building ‘for the perpetual prevention of famine in the province’.

The result was a highly imaginative edifice, which the locals named the Golghar (‘the round house’). Almost 100 feet tall and nearly 500 feet in circumference at ground level, it dominated the surrounding Indian dwellings, its summit providing views over the city of Patna to the Ganges, sacred river of the Hindus. Its dome-like structure would be recognised by the local population as resembling both a Buddhist stupa and the dome of an Islamic mosque. Ascending around the dome was a spiral staircase, for the use of Indian bearers carrying sacks of grain to be emptied through the hole in the top of the dome, gradually filling the internal hemisphere with sufficient grain to provide for any future famines. The Golghar would be judged to be ‘touched . . . with the machismo of the imperial presence . . . the most famous of the practical structures of the Raj.’

Captain Garstin ordered an inscription on the side of his architectural masterpiece, which announced that it was ‘First filled and publickly closed by . . .’ This proclamation remained forever incomplete. According to the visiting Victorian poet Emily Eden, the Golghar ‘was found to be useless’. When I visited Patna, and was shown this celebrated structure, still in good condition almost two centuries after its completion, I was informed of the reason for its redundancy. According to my guide, the door in the base of the dome, through which the grain should have poured out once it was filled, had in fact been constructed so that it only opened inwards.

Some modern sources dispute this significant detail, but when I visited Patna, I could find no one who was not adamant concerning the veracity of this incompetence, and consequent suffering, inflicted by the British. Such views may have been reinforced by the fact that many I spoke to were of sufficient age for the last Bihar famine of 1966–67 to have been more than a folk memory.

Our third tale of empire brings us into the modern times, when as we shall see many had good reason to believe that this would be the era of humanity’s last empires.The world’s two great empires appeared to be hell-bent upon destroying the world itself.

In 1945 the United States’ Manhattan Project under Robert Oppenheimer was in a race to complete the world’s first atomic bomb. Many of the scientists working under Oppenheimer at the remote Los Alamos site in the New Mexico desert had fled Germany as a result of the Nazi decrees against the Jews, and were referred to ironically as ‘Hitler’s Gift’ to the Western allies. Before Oppenheimer undertook the first bomb test, some of his leading scientists – most notably the Hungarian-Jewish Edward Teller – raised the possibility that a nuclear explosion might ignite the atmosphere and incinerate all life on earth. Oppenheimer assigned the head of his theoretical physics department, the German-Jewish Hans Bethe, to calculate the likelihood of this taking place.

Although the secret report he and Teller eventually produced claimed that such a conflagration was not possible, they did nonetheless feel constrained to add:

However, the complexity of the argument and the absence of satisfactory experimental foundations makes further work on the subject highly desirable.

The detonation of the first atomic bomb went ahead nonetheless.

The same question arose again in 1952 prior to the detonation of the first hydrogen bomb, this time masterminded by Teller himself. Once again, after meticulous calculations it was concluded that the possibility of atmospheric ignition was negligible. The first hydrogen bomb was duly tested. It immediately became apparent that not all the meticulous calculations concerning this bomb had been correct – or even approximately correct. The detonation itself proved to be two and a half times more powerful than the maths had predicted.

Within a few years, struggle between the two great empires competing for global domination, the United States and the Soviet Union, had achieved reductio ad absurdum: both had accumulated nuclear arsenals capable of destroying the world several times over. In 1962 their rivalry came to a head with the Cuban Missile Crisis. This was essentially an eyeball to eyeball confrontation between the USA and the USSR, where the Soviets ‘blinked first’ and Armageddon was narrowly averted. According to nuclear historian Alex Wellerstein, writing several decades later, the Cuban Crisis was ‘even more dangerous than most people realised at the time, and more dangerous than most people know now.’

This was but one of several ‘near-accidents’ in which one of the two great modern empires might have destroyed the world rather than accept defeat. Perhaps the best-documented incident concerns ‘the man who saved the world’. On 6 September 1983 Lieutenant-Colonel Stanislav Petrov was the duty officer in charge of the Serpukhov-15 nuclear early warning bunker outside Moscow. Just after midnight, one of his computers relayed information from a Soviet satellite that had detected an inbound American intercontinental ballistic missile.

In keeping with the ‘deterrent’ policy of mutually assured destruction (MAD), adopted by both the USA and the USSR at the time, Petrov should immediately have launched a massive simultaneous nuclear counter-attack. Instead, he decided that the computer reading must be an error and disobeyed his orders, on the grounds that if the US were to launch a first-strike attack against the Soviet Union, it would obviously involve more than one single missile. Soon, his computers indicated four more incoming missiles. Although Petrov had no means of verifying his hunch, he once again decided that these too were the result of a computer error, simply a remarkable coincidence. Once again, he desisted from launching a counter-attack.

According to later reports on this incident:

It was subsequently determined that the false alarms were caused by a rare alignment of sunlight on high-altitude clouds and the satellites’. . . orbits, an error later corrected by cross-referencing a geostationary satellite.

Each of these three tales illuminates aspects in the creation of empire: the sense of adventure, the administration involved, as well as the dogged pursuit and exercise of sheer power. And as we have seen, such achievements frequently incorporate elements of their own self-destruction – to say nothing of any ensuing imaginative distortion of the facts concerned. The multiplicity of synchronised organisation that goes into the creation and function of a great empire is certainly humanity’s most complex achievement, responsible for much of our formative historical evolution. Yet ironically, the annals of empire are frequently more concerned with ethos than historical record. Our impression of empire, whether informed or jingoistic, remains ambiguous to this day – as reflected in the following two brief images from modern culture.

In Franz Kafka’s short story, In The Penal Colony, a colonial officer shows a visitor the ingenious machine which has been developed by his master. Anyone found guilty of an offence is strapped into the machine, which then slowly and excruciatingly inscribes upon his body the law that he has broken, torturing him to death in the process. The colonial officer is so besotted with this machine that he insists upon personally demonstrating it to his visitor. Having set the machine to inscribe the words ‘Be Just’, he places himself inside it. Unfortunately, the machine has fallen into disrepair, so that instead of carrying out its intricate operation it goes out of control and begins to mutilate the officer, inflicting upon him an excruciating death. It is not difficult to interpret this enigmatic imperial image in all manner of ways, few of them optimistic.

The second image is equally paradoxical, if a little less excruciating. This comes from the film, Monty Python’s Life of Brian. In one scene, the leader of the People’s Front of Judea, played by John Cleese, holds a clandestine meeting where he delivers a speech urging the party faithful to throw off the yoke of the Roman Empire. He ends by demanding rhetorically: ‘What have the Romans ever done for us?’ One by one the party members come up with unsolicited suggestions, until eventually their leader is forced to exclaim exasperatedly:

All right . . . all right . . . but apart from better sanitation and medicine and education and irrigation and public health and roads and a freshwater system and baths and public order . . . what have the Romans done for us?

These three tales of empire, and the ensuing two images, may be viewed as paradigms of the wider generality of empire itself and how we have come to regard it.

All of which brings us to the thorny topic of what precisely constitutes an empire? What is its definition? Does this remain the same throughout world history? And indeed, what is the effect on world history of such entities? The Oxford English Dictionary definition of an empire is:

An extensive territory (esp. an aggregate of many separate states) under the sway of an emperor or supreme ruler; also an aggregate of separate territories ruled over by a sovereign state.

Here we have but a basic framework. Inevitably, over the centuries this will take on different guises – not all of which will involve what we would regard as progressive elements of evolution.

As indicated earlier, a description of empire must be deemed to subsume such elements as the spirit of adventure, administration, and power – initially in the form of war. Indeed, war and consequent subjugation of alien people would seem to be the formative impulse from which empire develops. ‘Civilising’ aspects frequently, but not invariably, follow. It seems no accident that civilisation (in its Western form) progressed across the globe more rapidly than ever before during the century which saw the first two world wars, followed by the threat of a third.

On the other hand, since the last decades of that century, and well into this one, the world has seen no major wars on that previous scale, while progress, especially in the form of the IT revolution and all that entails, has transformed the world as never before. Bearing in mind such multifarious aspects of empire, we can now begin to trace the history of the world as it is reflected in ten supreme examples of this phenomenon.