CHAPTER SIX

Braddock’s March

When the Alexandria conference broke up, Edward Braddock prepared to march on Fort Duquesne. The plan was to use the road that Washington’s Virginia Regiment had opened from Wills Creek to Red Stone Fort the previous summer, improving it to allow heavy artillery and a large supply train to pass. To perform this feat of engineering and execute the siege that would follow, he would rely on the old soldiers and new recruits of the Forty-fourth and Forty-eighth Regiments (about fourteen hundred in all), as well as companies of provincial soldiers from Virginia, Maryland, and North Carolina (a total of another thousand). In addition to these twenty-four hundred soldiers, four or five hundred civilian teamsters, horse wranglers, herdsmen, sutlers, and female camp followers also accompanied the expedition, providing support services from transportation to cooking, laundry, and nursing that the soldiers could not efficiently perform themselves.

Because the regulations that governed precedence in the army dictated that no provincial field officer (that is, major, lieutenant colonel, or colonel) should be superior in rank to any regular field officer, the provincials were organized as independent companies and included no officer above the rank of captain. Washington was eager to serve, but had too keen a sense of honor to accept demotion from provincial colonel to provincial captain. Braddock therefore invited Washington to join his official household as a “volunteer” and aide-de-camp—that is, as a civilian performing the same duties as Braddock’s other two aides, both regular-army captains. He would receive the same rations and respect as they, but no pay. Such arrangements were common in the British army, and service for a campaign as a gentleman volunteer often furnished the means for ambitious young men to gain appointments as officers. Braddock had a number of blank commissions to use in filling vacancies as they occurred, and Washington understood that one would eventually go to him.

WESTERN THEATER OF OPERATIONS, 1754-1760:

The Pennsylvania-Virginia Frontier to the Great Lakes

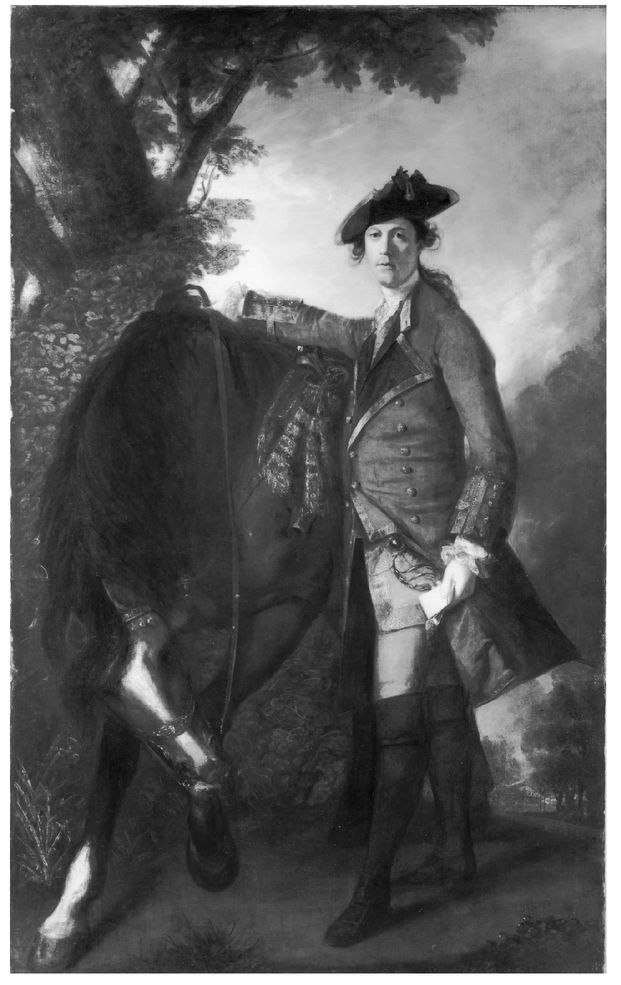

Captain Robert Orme, by Sir Joshua Reynolds. Captain Robert Orme (1732-1790) accompanied Major General Edward Braddock to Virginia in 1755 as an aide-de-camp. He developed a warm friendship with fellow aide George Washington. Orme was wounded on July 9, 1755, at the Battle of the Monongahela, and returned to Britain, where he posed for this portrait commemorating his American service. (© National Gallery, London)

Braddock assembled his expedition’s forces, wagons, and draft animals in May at Wills Creek, where he ordered a fort—which he named Cumberland, for his patron—to be built across the Potomac from the Ohio Company’s storehouse. What he needed above all was intelligence concerning the enemy’s strength and circumstances, and that could come only from Indian sources. To that end he had obtained the services of George Croghan, whose linguistic and cultural skills William Johnson had already recognized by appointing him as his deputy superintendent. Croghan in turn had used his contacts with Tanaghrisson’s band (Tanaghrisson himself had died at Croghan’s trading post the previous October) to invite Indians from the Forks to meet with Braddock at Fort Cumberland. In late May a delegation appeared, including the Oneida chief Scarouady, Tanaghrisson’s successor as Half King, and the Delaware chiefs Shingas and Delaware George. One member of the group, a Mohawk called Moses the Song, brought with him a plan of Fort Duquesne drawn by Captain Robert Stobo, one of the two officers whom Washington had left as hostages with the French in 1754. The delegates presented it in a gesture of goodwill that the general, in his ignorance, entirely disregarded.

The Ohio Indians were in fact quite interested in helping Braddock remove the French and the hundreds of French-allied Indian warriors—Potawatomis, Ottawas, Abenakis, and others—who had accompanied them to the Forks. They now dominated the region in ways infinitely more intrusive than the Iroquois ever had, depriving the Delawares, Shawnees, and Mingos of the self-rule they longed to exercise. All that Shingas and his fellow chiefs asked was that Braddock promise no permanent English settlement would be established in the Ohio country once the French had been driven out. Braddock, however, understood neither how much he needed the Indians nor how much they wanted his aid in establishing their independence. Thus when the chiefs asked him what he planned for the future of the Forks, he bluntly replied “that the English should inhabit and inherit the land.” Would he at least allow the Indians to live among the English, they asked, and leave them sufficient hunting grounds to support their families? Braddock’s gruff reply, “No savage should inherit the land,” convinced them that they had come to the wrong man for help. Replying that “if they might not have liberty to live on the land they would not fight for it,” all the Ohio chiefs but Scarouady returned to their homes and came to terms with the French.

Stobo’s map of Fort Duquesne. Following the Fort Necessity capitulation, two Virginia captains, Robert Stobo and Jacob Van Braam, returned to Fort Duquesne as hostages to ensure the repatriation of the surviving members of Jumonville’s party. Moses the Song, a Mohawk who was closely associated with Scarouady and Tanaghrisson (the Half King), smuggled Stobo’s plan of Fort Duquesne to Major General Braddock. (Archives nationales de Quebec—Centre de Montreal, Fonds Juridiction Royale de Montreal, TL4, S1, D6128)

Braddock, unconcerned at their departure, anticipated no problem in removing the French and their allies, for he was convinced he needed no Indian help to do it. “Savages,” he remarked to Benjamin Franklin, who had come to Fort Cumberland to help procure wagons and horses for the army, “may indeed be a formidable enemy to your raw American militia; but upon the king’s regular and disciplined troops, Sir, it is impossible they should make any impression.” It was a mistaken view, expressed by a man who had little personal experience with battle—least of all of the kind of battle that, in a little more than six weeks, would cost him his life.

Braddock’s column, perhaps two miles in length and gravid with cannon and supplies, left Fort Cumberland on May 29. Croghan had persuaded only Scarouady and seven Mingo warriors to accompany it, an entirely inadequate number of scouts. The march went slowly enough that Braddock, growing impatient at the end of the first week, decided to split the army into two divisions, and proceed with a “flying column” of twelve hundred picked men, together with about 250 camp followers and wagoners. The remainder of the army, under the command of Colonel Thomas Dunbar, would follow with most of the baggage and the heaviest artillery, improving the road as it went. The distance between the two bodies steadily lengthened; ultimately the flying column would be sixty miles ahead of the main body.

The march of the flying column went remarkably well, with Braddock deploying flanking parties for security and progressing at a rate of five or more miles per day. They knew they were being observed from the forest by French-allied Indians but, apart from a very small number of men taken and killed, suffered little as a result. In the small number of skirmishes with enemy scouts, the Indians fled at the first volleys, increasing Braddock’s confidence in the superiority of his men. By the time the column crossed the Monongahela a few miles southeast of Fort Duquesne early in the afternoon of July 9, he had no reason to expect anything but success. His troops had been most vulnerable to attack while fording the river. The absence of opposition at this critical moment seemed to indicate that the French had simply decided to abandon the Forks as indefensible. At any moment, Braddock thought, he might hear the roar of a great gunpowder explosion as the defenders demolished the fort and fled.

Rather than fleeing, however, the commandant of Fort Duquesne had dispatched nearly 900 men—637 Indians, 146 Canadian militiamen, and 108 troupes de la marine, or half his total force at the Forks—to intercept the invaders. Not knowing precisely where Braddock’s force would be, the defenders collided with it on the trail not far from the crossing, about six miles from the Forks. In the initial confusion of what eighteenth-century soldiers called a “meeting engagement,” the French captain who had been leading the force was killed by a random, long-range musket shot. Croghan, Scarouady, and the Mingo scouts retreated along with the advance party of British soldiers under Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Gage. The sudden death of the French leader confused and disorganized the militia and troupes de la marine, but the Indians continued the attack without need of direction. Largely made up of northern warriors (among whom were Charles Langlade and his Ottawa kinsmen from Detroit) but also including substantial numbers of Shawnee, Delaware, and Mingo fighters, they dispersed into the woods on both sides of the road and began picking off the scarlet-coated enemy.

The British made it substantially easier for the Indian marksmen to do their work. Hearing firing erupt ahead, the main body of the column rushed forward, colliding with the retreating advance guard. Tangled in confusion on a road little more than twelve feet wide, the British made a splendid, defenseless target. Unable to see the Indians who sniped at them from cover, the British troops fought as best they could, directing volleys blindly into the woods—and also, all too often, into one another.

Braddock, splendidly brave, sat astride his horse in the midst of the chaos, trying to direct his men’s fire and attempting to re-form them into coherent units. Two of his aides, wounded, could not carry on their duties; the third, Washington, remained untouched as he rode beside Braddock despite having three horses shot from beneath him and his coat and hat repeatedly pierced by bullets. For all their confusion and fear, however, the British troops did not flee until a musket ball smashed into Braddock’s back, knocking him from his horse after three full hours of fighting. By then more than two-thirds of the 1,450 men and women in the British column had been killed or wounded. Sixty of Braddock’s eighty-six officers were among the casualties.

Though no one in Braddock’s shattered force knew it, the moment the survivors were the safest they had been all day was the moment they broke and ran, following the wounding of Braddock. The Indians, having won a great engagement, now concentrated on seizing plunder and captives. Finding the army’s stock of rum—two hundred gallons of it—in the abandoned supply wagons soon distracted them further, and an increasingly disorderly celebration ended what had been a remarkably lopsided battle. The Indians and French had suffered casualties of just twenty-three dead and sixteen wounded. For the panicked, exhausted British the next two days of flight became a new kind of hell. Men too seriously wounded to walk were left to die as their comrades stumbled down the road without food or water, convinced that the enemy would fall upon them at any moment. Braddock, carried from the battlefield on an ammunition cart, jostled along in agony for days, dying only when he reached the army’s rear element, near the site of the Jumonville massacre. His sole unwounded aide, Washington, arranged to have him buried in the road, so the army could march over the grave and obliterate any trace of it. The intention was to keep the body from being exhumed and mutilated by the Indians, who, the British believed, might attack once more. It is not impossible that many of the battle’s survivors welcomed the opportunity to grind their heels into the grave of the man who had led them to slaughter.

Once the survivors had reunited with Colonel Dunbar’s troops, the British force numbered two thousand, with more than thirteen hundred men fit for duty—a strength great enough to renew the campaign against Fort Duquesne. The demoralized and frightened Dunbar, however, found it impossible to order the men back down the road. Had he been able to, they would have arrived to find the fort virtually defenseless. The Ottawas and other northern Indians, having acquired the plunder and captives they had come to take, went home after the battle, leaving the commandant with too few men to withstand a siege. Not knowing this, and fearing that a French and Indian force might materialize from the forest at any time, Dunbar ordered the remnants of the largest military force British America had ever seen to destroy supplies, mortars, and ammunition and march for Philadelphia with all possible speed. There he completed the redcoats’ humiliation and disgrace by demanding, in July, that the city provide them with winter quarters.

“D’une nouvelle terre” (lyrics). The Catholic chaplain Denys Baron penned these lyrics at Fort Duquesne following Braddock’s defeat. Thanking the Virgin Mary for the surprising victory, Baron concluded with a premonition of the bitter struggle to come:

The survivors of the Virginia provincial companies—those who did not desert—remained at Fort Cumberland. There Governor Dinwiddie ordered them reconstituted as the Virginia Regiment and offered Washington the command. The reappointed colonel thereupon undertook the task that occupied him for the next three years: defending more than three hundred miles of backwoods settlements along the whole length of the Shenandoah Valley. To the north, Pennsylvania’s frontier had no defenders at all. Using Braddock’s road as their warrior’s path, Ohio Indian raiding parties now brought devastation down upon the frontiers of two of the richest, most populous colonies in British America. Western settlers by the thousand fled their farms for the presumed safety of settlements farther east. Thus began the greatest refugee crisis in the history of the colonies, and the most widespread war British North America had ever known.

“Great Mother, support our poor country that belongs to you / Make our lily flowers bloom / The English are raising their flags at our own border / Answer our prayers, fortify our ramparts.” (Archive du Monastère des Augustines de l’Hôtel-Dieu de Quebec)