CHAPTER TWELVE

The Red Cross of Carillon

The first battle of 1758 seemed to confirm what Pitt dreaded most. Following Loudoun’s unceremonious departure in March, preparations for the campaigns had moved ahead quickly. Men came forward to enlist with an enthusiasm fueled in equal parts by patriotic feeling and the exceptionally generous bounties the provincial assemblies offered once they knew that Parliament would reimburse them in proportion to their participation in the war effort. By the beginning of July General Abercromby had established his headquarters next to the hulk of Fort William Henry, in the midst of the largest armed force ever assembled in North America, some sixteen thousand men. With sixteen heavy cannon, thirteen howitzers, eleven mortars, and eight thousand rounds of ammunition, the expedition’s artillery train was sufficient to conduct sieges against every post from Fort Carillon to Montreal. A thousand boats had been built to transport men, guns, and baggage down the lake. When the army set out at dawn on July 5, the flotilla of sailing vessels, bateaux, and whaleboats moved in four parallel columns that stretched seven miles from end to end.

The marquis de Montcalm had arrived at Fort Carillon less than a week before. There he found eight understrength battalions of troupes de terre, one company of troupes de la marine, thirty-six Canadian militiamen, and fourteen Indians. Their food supply was sufficient for perhaps nine days. More men arrived thereafter, but by the morning of July 6, when members of the French advance guard came running with the unwelcome news that a British force large enough to cover the face of the lake was landing just four miles from the fort, Montcalm had only 3,526 men at his disposal. The provisions on hand, including every morsel the reinforcements had brought, would not sustain them for a single week. What made matters even worse was that Fort Carillon had been built in such haste following the Battle of Lake George that it was extremely difficult to defend. A seven-hundred-foot hill, now known as Mount Defiance, overlooked it from the west, less than a mile away, offering an ideal spot from which gunners could fire directly into the interior of the fort. To the north, a quarter-mile from the north bastion, a low hill presented another advantageous location for an enemy battery. Captain Pontleroy, Montcalm’s chief engineer, minced no words in describing the post’s vulnerability. “Were I to be entrusted with the siege of it,” he reported, “I should require only six mortars and two cannon.”

“Plan du Fort de Carillon.” This contemporary plan illustrates the high ground north of Fort Carillon on which Montcalm’s forces erected an irregularly shaped defensive wall and abatis. Montcalm’s regular battalions encamped between the height of land and the fort, the locations marked here by rectangular icons. (William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan)

Because Fort Carillon stood little chance of surviving a determined cannonade, Montcalm decided to oppose the invaders on the high ground to the north. On the evening of the sixth he laid out a line of entrenchments in a thousand-yard-long semicircle around the shoulder of the hill that commanded the only route to the fort from the land side. The next morning he and his fellow officers wielded axes to set an example for their men in felling trees and interweaving their sharpened branches to form a broad tangled barrier forty or fifty yards deep on the slopes below the trenches. The barrier of fallen trees, called an abatis, had a purpose identical to that of the rolls of concertina wire that enclose modern field fortifications: to arrest the progress of attackers and expose them to systematic destruction by the fire of small arms and field artillery. By sundown both the abatis and the entrenchment—now reinforced with a log breastwork topped by “wall pieces” (small-bore cannon mounted on swivels) and sandbags—stood ready.

Montcalm was grateful, if surprised, that he had been given time enough to complete this hasty fieldwork. Yet he knew that at most it could delay the British advance. Secure as it was against small arms fire, the log breastwork would become untenable as soon as the British brought even a few fieldpieces to bear on it; every cannonball that struck would dislodge a deadly hail of splinters that would soon drive the defenders back to the fort. Unless Abercromby proved so impetuous (or mad) as to order an infantry assault through the abatis, there was no realistic prospect that it would become the site of a decisive engagement.

Yet that, seemingly, was exactly what Abercromby did in the midday heat of Thursday, July 8. Two days before, near the army’s landing place, Lord Howe had been killed while leading a detachment in pursuit of the French guards as they retreated through the woods. Abercromby, who reported to Pitt that he had “felt [Howe’s death] most heavily,” seems to have been at a loss for the rest of that Tuesday. While the French had worked feverishly to complete the trenches and abatis on Wednesday, Abercromby had recovered enough of his composure to march his men forward to within a mile and a half of the fort. A small party sent out to reconnoiter the French position brought word that the French were entrenching around a hill athwart the road to the fort, and speculated that the breastwork, which had not yet been completed, could be carried by storm. Abercromby, who did not go forward to see for himself, decided to make the attack the following day.

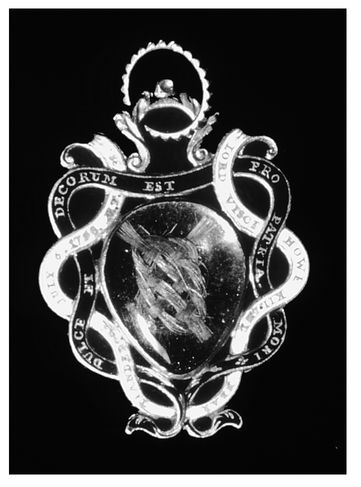

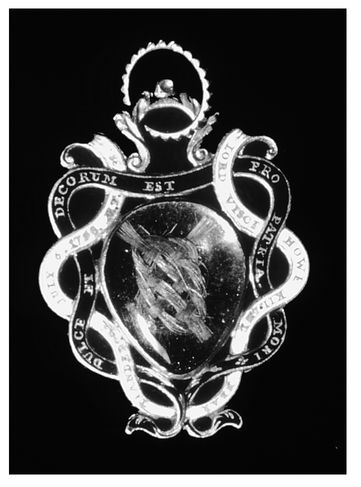

Mourning locket. This mourning locket contains a lock of hair from George Augustus, Viscount Howe (c. 1725-1758), colonel of the British Fifty-fifth Regiment and Abercromby’s deputy commander on the expedition against Fort Carillon. Howe’s death in a confused skirmish shortly after the British landing at the foot of Lake George affected Abercromby deeply, and may have contributed to the failed attempt to storm Montcalm’s defensive works on July 8, 1758. (Collection of the Fort Ticonderoga Museum)

By noon on Thursday eight regular battalions—about seven thousand men—were drawn up opposite the breastwork in battle order and readied for a frontal assault. Six thousand provincials formed the reserve. The army’s heavy siege artillery, which would have taken another day or more to move forward, remained parked near the landing place, four miles away. The assault, however, was not to be made without artillery support. Four field guns—three six-pounders and a howitzer—were loaded on rafts and towed down the Rivière de la Chûte, to be landed near the base of Mount Defiance. These were to be dragged up the hill, from which they could fire down on the rear of the French lines. The British infantry would attack when the battery opened fire.

Unfortunately for the men drawn up to make the attack, the planned cannonade never began. The towboat crews overshot the place where they should have landed, and drifted within range of the cannon on the south-west bastion of Fort Carillon. The fort’s gunners, noticing what was afoot, fired on the British boats, sinking one of the rafts and so endangering the boats that the officers in charge ordered the remaining raft to be rowed back upstream to safety. The two remaining cannon were never landed or brought to bear on the French fieldworks.

In all likelihood it was the sound of French cannon shelling the rafts that caused the British troops to advance at about twelve-thirty. Abercromby, who stood on a rocky outcrop from which he could observe the battlefield, apparently did not give the order to charge. The attack, which began raggedly, gathered momentum as regiment after regiment, seeing its neighbor move ahead, advanced into the abatis. According to a lieutenant in the Highland (Forty-second) Regiment, once “the fire became general on both sides” it grew “exceedingly heavy,” and continued “without any intermission; insomuch that the oldest soldiers present never saw so furious and so incessant a fire.” The abatis, he reported, “was what gave them the fatal advantage over us.” The entangled branches of its “monstrous large fir and oak trees . . . not only broke our ranks, and made it impossible for us to keep our order, but . . . put it entirely out of our power to advance briskly; which gave the enemy abundance of time to mow us down like a field of corn, with their wall pieces and small arms, before we fired a single shot.”

Hopeless as they were without artillery support, the British attacks continued until seven o’clock that evening. At least 551 redcoats and provincials died and more than thirteen hundred were wounded trying to come to grips with the thirty-six hundred well-protected French and Canadian troops who methodically cut them to shreds. The Battle of Ticonderoga, as the Anglo-Americans called it, was the heaviest loss of life that His Majesty’s forces sustained during the whole American war. It was, in fact, the bloodiest day the British army would see in North America until the Battle of New Orleans in 1815. The French, by contrast, suffered a total of 377 casualties.

Montcalm expected that the British would renew the attack the next morning, and was surprised when they did not. Suspecting that the enemy had feigned retreat in order to draw him out of his lines, he waited until Saturday before sending out a reconnaissance party to see what had become of his enemy. What they found—“wounded [men], provisions, abandoned equipment, shoes left in miry places, remains of barges and burned pontoons”—was evidence of the panic that had gripped Abercromby’s defeated force late Thursday night. Following the battle, the men had withdrawn to their original staging area, a mile from the battlefield. Hours later, Abercromby had given the order to pull back to the landing place, three miles farther back. His intent was to reorganize his forces the following morning. The men, not knowing the reason for the withdrawal, believed that they were about to be attacked by the French and stampeded for the boats. By dawn the greatest army Britain had ever assembled in North America was rowing frantically for the other end of Lake George, fleeing an enemy that it still outnumbered by more than three to one—an enemy that at that moment was preoccupied with strengthening its fortifications against the British attack that would never come.

When Montcalm finally grasped what had happened, the only possible explanation that came to him was that God himself had intervened to preserve His Most Christian Majesty’s dominions in North America. On July 12, he and his men sang a

Te Deum for their deliverance. In late August he ordered a huge red cross to be raised on the hilltop above the abatis where Abercromby’s troops had poured out their lives for nothing. On the cross Montcalm directed that a Latin couplet of his own composition be inscribed, along with its paraphrase:

Chretien! Ce ne fut point Montcalm et la prudence,

Ces arbres renversés, ce héros, leur exploits,

Qui des Anglais confus ont brisé l’espérance;

C’est le bras de ton Dieu, vainqueur sur cette croix.

Christian, behold! Not all the care that Montcalm took,

Nor this fearsome abatis, nor all our heroes’ feats

Have stunned the English here, have shattered all their hopes;

Instead the arm of God prevailed, the victor of this cross.

4The Battle of Ticonderoga marked Montcalm’s greatest victory—not only over the hapless Abercromby and his vastly superior army, but over Vaudreuil as well. In reports to the ministry he claimed the governor-general was responsible for the small numbers of troops on hand to defend against the British onslaught, and blamed him for the lack of Indian scouts and raiders. He similarly overstated the numbers of enemy casualties his men had inflicted, inflating Abercromby’s numbers to twenty-five thousand and claiming that as many as five thousand of them had been killed in the battle. None of this was true; all of it supported Montcalm’s plea to be given plenary control over the war effort in Canada. He sent his chief aide, Louis-Antoine de Bougainville, along with the reports, to make his case at Versailles. He must be free, he argued, to use his regulars to mount a concentrated, conventional defense of the capital and its surrounding settlements—a defense that would mimic, on a vastly larger scale, his hedgehog tactics of July 8.

Vaudreuil realized how vulnerable he had become, and quickly dispatched his own emissary with a set of proposals for the defense of Canada in the coming year. The governor-general advocated the renewal of guerrilla strategies and begged for resources to revive the Indian alliances that had flagged in the aftermath of Fort William Henry. His strategy remained the classic one of dispersed attacks against the Anglo-American frontiers. In the event of a British invasion of the Saint Lawrence, he proposed the evacuation of the civilian population from the lower valley to Trois Rivières. If Quebec became untenable, Canada’s defenders could retreat to Montreal.

Detail of engraved powder horn, c. 1759. When British forces under Major General Jeffery Amherst took Fort Carillon in 1759, a British or provincial soldier carefully inscribed this powder horn with a map of the territory between Lake George and Crown Point. This detail includes a unique depiction of the cross Montcalm’s forces erected on the Height of Carillon. (Courtesy of Jim and Carolyn Dresslar)

Bougainville returned in April 1759, carrying the decision of Louis XV in favor of Montcalm and a professionalized, Europeanized war. By then, however, the outcomes of the other campaigns of 1758 were known, and it was clear exactly how far the military balance in North America had shifted. Montcalm might have the power for which he had so ardently wished, but he would also face an enemy that would be as unstoppable in fact as Abercromby’s army had seemed to be in appearance.