CHAPTER FOURTEEN

Colonel Bradstreet’s Coup

Oddly enough, it was a Nova Scotian of Acadian descent who engineered Britain’s second victory of 1758, the taking of Fort Frontenac on August 27. Jean-Baptiste Bradstreet, born forty-four years earlier to an Acadian mother and a British army lieutenant, had literally grown up in his father’s regiment, the Fortieth Foot, which he joined as an ensign in 1735. A chance meeting with William Shirley in 1744 helped persuade the governor of Louisbourg’s vulnerability and led to Bradstreet’s participation in the expedition of the following year. His organizational expertise and initiative so impressed the governor that Shirley sought him out a decade later when he needed someone to organize a transport service to carry supplies by bateau from Albany to Oswego. It was a testimony to Bradstreet’s talents that Lord Loudoun left him in charge of transport notwithstanding his connection with Shirley, and even promoted him to the rank of lieutenant colonel. Loudoun’s later decision to make Bradstreet his deputy quartermaster general testified to his willingness to reward the colonel’s success, if not his virtue. Tireless as he was in improving the army’s logistical position, Bradstreet (like many a quartermaster in history) was also committed to enhancing his own financial position, and ultimately made himself a rich man by exploiting his office for private advantage.

Welcome as it was, wealth did not quench Bradstreet’s thirst for military glory, and he never ceased promoting a plan he had first conceived in 1755 for seizing Fort Frontenac. This post, the linchpin of Canada’s trade and supply system for every post west of Montreal, offered perhaps the richest single prize in New France. Its warehouses concentrated all the furs harvested in the pays d’en haut until they could be carried down the Saint Lawrence for shipment to France; the arms, ammunition, and trade goods fundamental to the Indian trade and alliance system likewise paused at Fort Frontenac to be assembled into cargoes for sailing vessels to carry west. To seize the post would destroy Canada’s naval base on Lake Ontario and deprive every fort above it in the Great Lakes Basin of the supplies it needed to remain tenable. Most significantly for the inhabitants of Pennsylvania’s and Virginia’s battered frontiers, the cutoff in trade goods and ammunition to Fort Duquesne would weaken France’s alliance with the Indians of the Ohio country.

NORTHERN THEATER OF OPERATIONS, 1754-1760:

New York, New England, New France,

and the Lake Champlain-Richelieu River Corridor

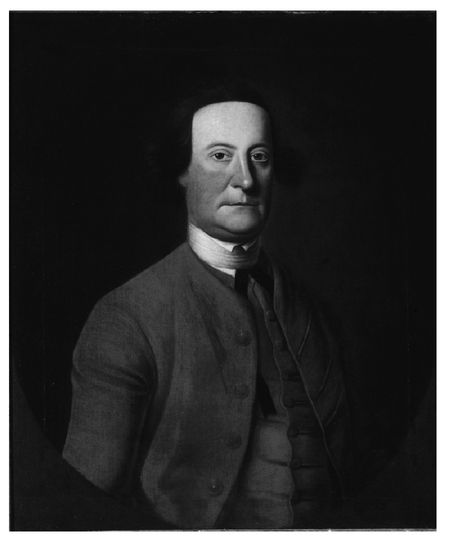

General John Bradstreet, by Thomas McIlworth, 1764. The son of an Acadian mother and a British army officer, Jean-Baptiste (John) Bradstreet led the corps of armed boatmen who were responsible for the transport and supply of British and provincial forces in the Lake George and Mohawk River regions after 1755. Bradstreet’s swift waterborne expedition against Fort Frontenac in August 1758 struck a telling blow against the French posts of the pays d’en haut and buoyed morale in British North America following the disastrous attack on Fort Carillon. (Courtesy of William Reese)

Loudoun, impressed both by Bradstreet’s announced willingness to pay for an expedition against Fort Frontenac out of his own pocket and by the strategic elegance of the plan, made it part of the projected New York campaign in 1758. Pitt, who lacked detailed knowledge of local circumstances in America, thought it superfluous, and omitted it from his list of approved operations when he sacked Loudoun. When James Abercromby succeeded to the post of commander in chief, he let the matter drop, but the catastrophe at Ticonderoga altered everything. Within hours of Abercromby’s beaten army’s arrival back at the head of Lake George, Bradstreet laid siege to the badly shaken commander in chief with requests for men and arms to attack the fort. Worn down no less by Bradstreet’s badgering than by the humiliation of defeat, and desperate to salvage something from a ruined campaign, on July 13 Abercromby gave in. In two weeks’ time Bradstreet had assembled a task force at Schenectady made up of 184 regulars, 70 Iroquois warriors, and more than 5,000 provincials from New England, New York, and New Jersey. In short order he equipped them with bateaux, supplies, and field artillery, and before the month was out they were rowing westward up the Mohawk.

Their destination, as Bradstreet elaborately explained to them (and to everyone else in earshot at Schenectady), was the Great Carrying Place, the portage between the headwaters of the Mohawk and those of Wood Creek, whose waters flowed west toward Lake Oneida and Lake Ontario. They would build a new fort here and reoccupy ground that the British had abandoned two years earlier, after the fall of Oswego. This was ostensibly a goodwill gesture, for the Six Nations had lacked access to trade goods in the heart of Iroquoia for two years; that was why the chiefs of the Onondaga and the Oneida provided warriors as an escort. It was also an elaborate ruse intended to deceive the French (whom the Iroquois could be counted on to inform) about the expedition’s real intent, the seizure of Fort Frontenac. Only after the troops’ arrival at the Carrying Place did Bradstreet and Brigadier General John Stanwix, the expedition’s nominal commander, reveal their true mission. About half of the warriors left the expedition as soon as they learned its goal. Bradstreet kept the rest by promising them first claim on the booty that Fort Frontenac would be sure to yield.

Thus General Stanwix remained at the Carrying Place with two thousand men to build a fort while Bradstreet and the remaining three thousand lugged their boats and matériel, including eight cannon and more than five hundred rounds of ammunition, across the portage, then dropped down Wood Creek toward Lake Ontario. On August 21 they encamped by the ruins of Oswego; four days later, still undetected, they beached their boats on the Cataraqui promontory within a mile of Fort Frontenac. They threw up hasty defenses against the cannonballs the surprised French began to fire in their general direction, and waited for the next morning. At dawn they landed their field guns, mounted them on carriages, and hauled them to an improvised battery in a breastwork the French had abandoned, just 250 yards from the fort’s western wall. That evening Bradstreet’s men seized a hill even closer to the fort—150 yards from its northwest bastion—and erected a second battery. As day broke on August 27, all eight of Bradstreet’s guns opened fire. In less than two hours a red flag of truce fluttered above the fort’s battlements.

Bradstreet was astonished by the lack of effective opposition from the fort. He understood it better when he found that Frontenac’s sixty-three-year-old commandant, Major Pierre-Jacques Payen de Noyan of the

troupes de la marine, had only 110 men under his command, while the fort held many women and children, the dependents of garrison members who earlier had been sent to aid in the defense of Fort Carillon. Noyan had no shortage of supplies, guns, or ammunition, but could man fewer than a dozen of his fort’s sixty cannon. Knowing that the post’s aged walls could not withstand sustained bombardment, he had despaired of holding out for the week or more that it would take for reinforcements to arrive from Montreal, two hundred miles down the Saint Lawrence.

5Bradstreet lost no time in accepting Noyan’s surrender, for within the fort he had seen enough freshly baked bread to feed four thousand men, and he had no idea of how near a relief expedition might be. He therefore allowed the fort’s troops and civilians to leave with their personal possessions in return for Noyan’s promise that an equal number of Anglo-Americans held captive in Canada would be released; then he and his men set about plundering the richest post in the interior of North America. Bradstreet’s troops were staggered by what they found in the fort’s stores: hundreds of bales of cloth, laced and plain coats and shirts by the thousand, vast numbers of deerskins, beaver pelts, and other furs, great quantities of small arms and ammunition, and other “warlike Stores of all Sorts for the Endions.” There was too much to carry off; in the end, however, Bradstreet’s men succeeded in cramming booty worth £35,000 sterling in the holds of a brigantine and a schooner that lay at anchor in the harbor behind the fort. They destroyed what they could not carry, along with the remainder of the shipping (seven vessels, the whole of the Lake Ontario squadron), burned the buildings of the post, and used the great stocks of gunpowder in the fort’s magazines to blast its walls to rubble.

With enormous satisfaction Bradstreet took stock of the destruction on the afternoon of August 28. Then he ordered his troops to board their boats and make for Oswego, knowing that he had broken the back of the French supply system in the Great Lakes Basin. And he had done it without the loss of a single man.