CHAPTER TWENTY

General Amherst Hesitates

Word of Niagara’s fall reached Jeffery Amherst as he surveyed the ruins of Fort Saint Frédéric at Crown Point on the evening of August 4. His campaign, the most powerful of the year in the number of troops engaged, had been remarkably easy—a fact that only magnified his sense of unease. After a start delayed by a shortage of matériel and the tardy appearance of the provincials from New England, he arrived before the walls of Fort Carillon on July 22, resolved to avoid Abercromby’s mistake by conducting a siege in the most systematic possible way. To his surprise—almost, one imagines, to his disappointment—the twenty-three-hundred-man garrison held out only four days, barely giving his gunners a chance to open fire before taking to their boats, detonating the fort’s powder magazine, and retreating down Lake Champlain. Amherst, puzzled and cautious, ordered rangers to scout northward to Crown Point, where he expected the withdrawn garrison to add its strength to the troops at Fort Saint Frédéric and make a stand. He was astonished when they returned on August 1 and reported that the French had blown up that fort, too, and withdrawn north toward the fortified island that guarded the Richelieu River, Île-aux-Noix.

Amherst had therefore detached a thousand men to rebuild and garrison the shattered post he renamed Fort Ticonderoga and moved on to Crown Point, which he found in such ruins that he determined it would be necessary to build an entirely new fort on the site. The news from Niagara, encouraging as it was, did not settle his mind as he contemplated his next move. Amherst had begun the campaign with seven battalions of redcoats and nine of New England provincials, plus nine companies of rangers and a train of artillery, about eleven thousand men in all. He had detached a thousand men at the head of Lake George to construct and man a new post, Fort George, on the site of William Henry, and had left even more at Ticonderoga. If he detached still more to start work on a new Crown Point fort, he would be pursuing a retreating French army of unknown strength with a severely diminished force of his own, perhaps consisting of only four or five thousand men.

Amherst did not know the enemy’s destination with any certainty, but if as he suspected they were awaiting him at the foot of the lake, he would have to navigate eighty miles of water to reach them. That was a very long way from any secure base of supply, and he had only bateaux to transport his men and their artillery down the lake. Meanwhile, he knew that the French retained a small but potent squadron of sailing vessels—a schooner and three xebecs that between them mounted thirty-two cannon—that could turn his bateaux to matchwood in short order. Amherst did not dare to move forward, then, until he had armed sailing ships to defend his boats. He had earlier directed his shipwrights, back at Ticonderoga, to construct two powerful vessels—a twenty-gun brigantine and a radeau (an eighty-four-foot floating battery that mounted six twenty-four-pound cannon); now he ordered them to build an additional sixteen-gun sloop. To build, rig, and arm them all took until the second week of October. In the meantime Amherst ordered his men to press ahead not only with the construction of the forts at Ticonderoga and Crown Point, but a new road as well, to run the seventy-seven miles from Crown Point to Fort Number 4 on the upper Connecticut River (the site of modern Charleston, New Hampshire), in order to secure access to supplies and reinforcements from New England.

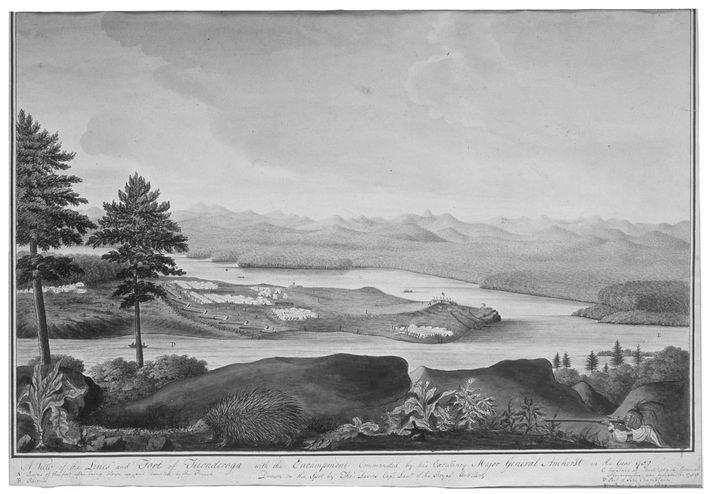

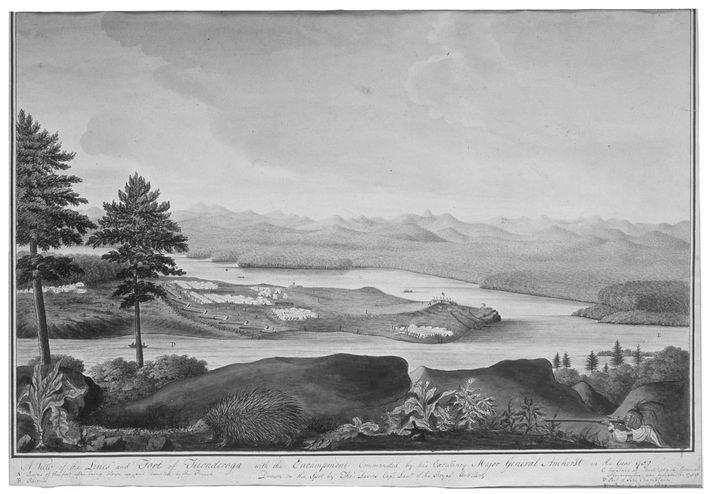

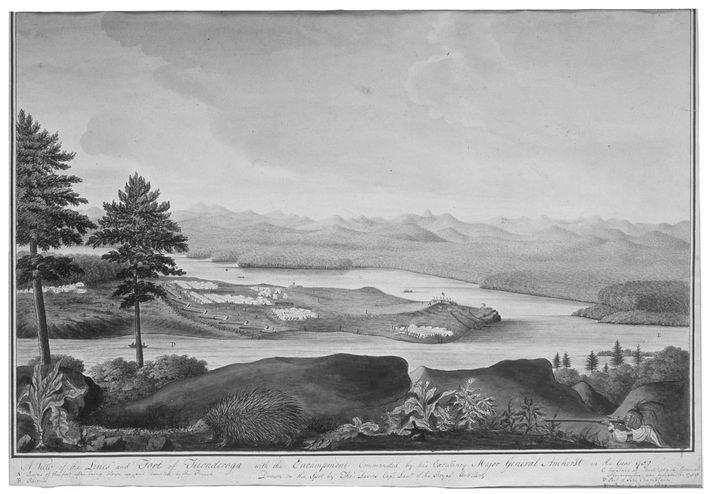

“A View of the Lines and Fort of Ticonderoga,” by Thomas Davies, 1759. An artillery officer produced this elegant view of Ticonderoga as seen from Mount Defiance in the summer of 1759. On the promontory stand the “ruins of the fort after being blown up and deserted by the French.” Zigzagging across the peninsula to the left are “the Lines at which . . . General Abercrombie was defeated in 1758.” Masses of white tents indicate the position of three Anglo-American encampments. Also note the foreground, where an Indian hunter (lower right) draws a bead on a very large porcupine. (Accession number 1954.1, negative number 38262a. The New-York Historical Society)

Amherst’s desire not to be lured into a trap proceeded not only from his native caution but also from his utter ignorance of Wolfe’s progress at Quebec. He had tried to make contact with Wolfe by sending a couple of bold regular officers overland with a small escort of Mahican Indian rangers, but these had been taken captive by the Abenakis of the Saint François réserve, midway between Montreal and Quebec. Amherst knew this because Montcalm reported it to him, with elaborate politesse, in a letter sent under a flag of truce. The letter, written at Quebec on August 30, told Amherst nothing of the state of affairs on the Saint Lawrence other than that, at least by that time, Wolfe had not succeeded. There was no word from a third messenger, who had taken a more circuitous route. In the absence of intelligence, Amherst’s sense that Wolfe would fail to take Quebec took on the force of conviction. And if Wolfe had failed, Amherst knew, Montcalm would be sure to shift troops from the Saint Lawrence to Île-aux-Noix. Montcalm might even try to launch a late-season attack on Crown Point. In view of so many unknowns, Amherst felt he could not be too cautious.

He therefore took pains to secure his position on Lake Champlain while investing no great energy in speeding the attack on Île-aux-Noix. Instead he contented himself with the construction projects at which he excelled, sent a large detachment of rangers under Major Robert Rogers to attack the Abenakis at Saint François, and waited for his vessels to arrive from the shipyard at Ticonderoga. It would be October 11 before he felt ready to order his men on board their bateaux and ships to move against Île-aux-Noix. Within a week the weather, turning cold and stormy, put an end to his resolve to proceed. On the nineteenth dispatches arrived to inform him that Quebec had indeed fallen, but by then it was too late in the season to do anything but suspend operations. By the twenty-first Amherst and his men were back at Crown Point, where he made preparations to send the regulars into winter quarters and to allow the provincials to return home. A month later he left for New York, to begin laying plans for a final thrust into the heart of Canada.