CHAPTER TWENTY-FIVE

Insurrection

The great Indian war that erupted at Fort Detroit on May 9, 1763, utterly surprised the man who did more than anyone else to provoke it, General Sir Jeffery Amherst.

8 The surrender of Canada had left him with an immense set of problems to solve, beginning with the administration of territories that (in theory, at least) extended from Labrador to the Mississippi to the Gulf of Mexico, and which included more than eighty thousand French Catholics and an unknowable number of Indians. To garrison and supply Britain’s forts from Louisbourg, on Cape Breton Island, to Fort Loudoun, in what is now Tennessee—a distance equal to that from Paris to Moscow—

and to occupy the enemy posts that had come into his control as well was simply beyond his capability. He had no choice but to continue to call on the provincial governments for men to garrison Britain’s forts and money to pay and supply them, and even to rely on the French officers in command of the more remote interior forts to retain control of them and the surrounding regions.

As Amherst’s administrative responsibilities exponentially increased, his financial and manpower resources withered. The conquest of the French West Indian islands and Cuba required him to provide large numbers of redcoats from what had come to be known as “the American Army.” Half of them never returned. Among those who did, large numbers came back crippled by wounds or debilitated by tropical disease. Meanwhile the enormous financial demands that came with carrying out naval operations on the Atlantic and in the Indian Ocean and campaigning in Europe, the Caribbean, and India caused the War Office to make deep cuts in Amherst’s budget. There had been little enough money in it in the first place—Amherst had on several occasions been forced to ask the New York assembly for loans to tide him over between shipments of specie—and there were few places where he could cut expenses. The one that he concentrated on, the Indian department, proved to be the worst of all possible choices.

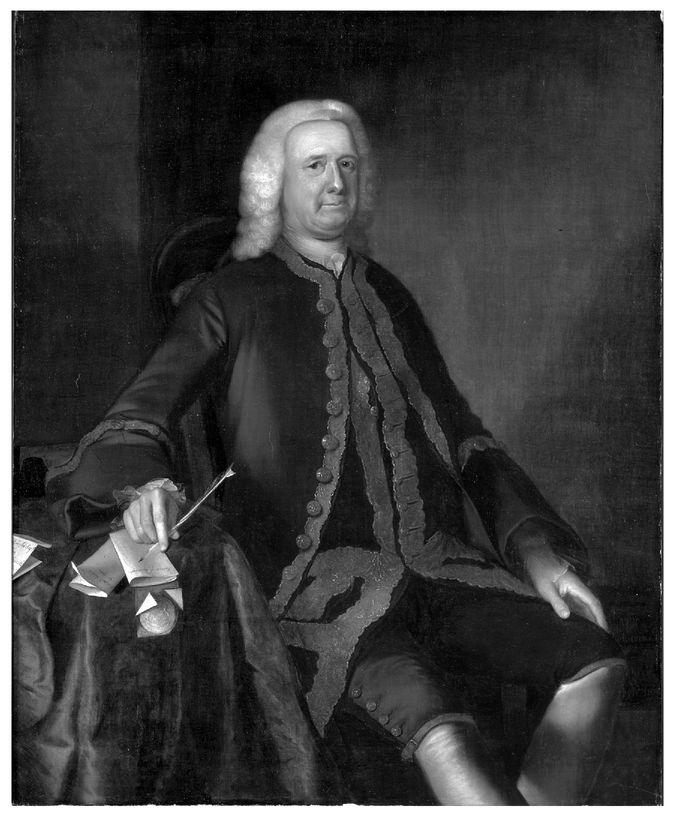

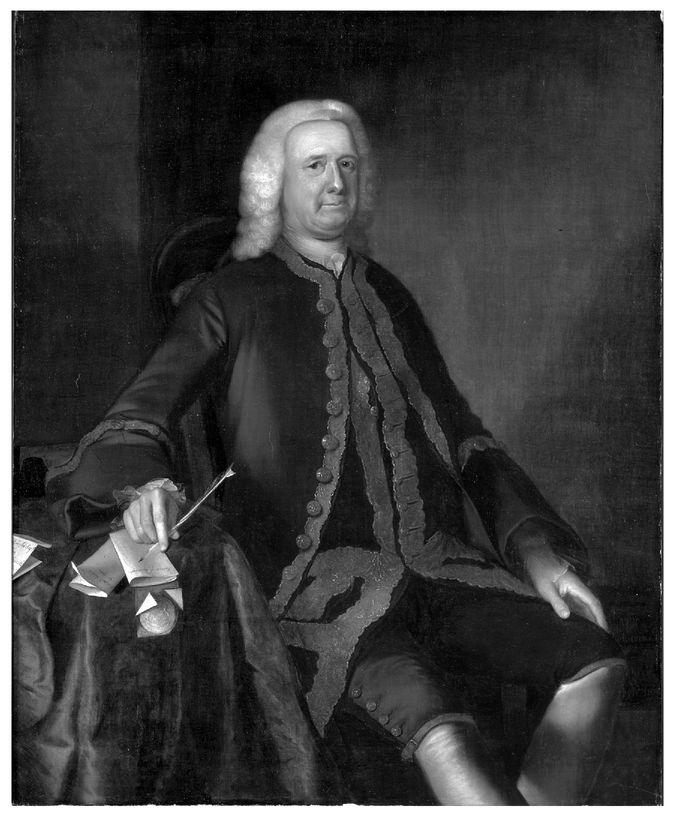

Portrait of Colonel Theodore Atkinson, by Joseph Blackburn, 1760. Theodore Atkinson (1697-1779) served as provincial secretary of New Hampshire through the French and Indian War. One of the papers arranged beneath his right hand reads “Enlistmts returnd/for 1760”—a reference to the province’s heavy contributions of manpower to the final campaign against New France. (Worcester Art Museum, Worcester, Massachusetts, museum purchase)

In the fall of 1761 Amherst suspended the practice of distributing gifts to Indian allies, including the customary provision of ammunition. The trading relations that had been established with local peoples at the various posts, he believed, sufficed to fulfill the promises made at Easton and by other treaties. If Indians were not being continually “bribed” with hand-outs, he thought, they could not indulge their proclivity for idleness. As he explained to an incredulous Sir William Johnson, the cessation of regular gift-giving “will oblige them to Supply themselves by barter, & of course keep them more Constantly Employed by means of which they will have less time to concert, or Carry in to Execution any Schemes prejudicial to His Majesty’s Interests.” It would be particularly wise, he thought, to keep “them scarce of Ammunition . . . since nothing can be so impolitick as to furnish them with the means of accomplishing the Evil which is so much Dreaded.” Finally, having observed the vastly destructive influence of alcohol on native communities, he also forbade all further trade in rum and other liquors, which had become a mainstay of the Indian trade because they were consumable items that fed an essentially bottomless demand. To prohibit access to alcohol, Amherst believed, would not only increase the ability of Indians to be productive hunters, but reduce the violence that plagued their villages and improve their character in general.

What made matters even worse in the view of the western Indians was that the British had failed to establish trading posts in the interior and then withdraw their troops from the region, as they had promised. Rather they had continued to maintain garrisons there, in imposing posts that suggested nothing so much as permanent occupation. (Surely it was impossible for the Ohio Indians to draw any other inference from Fort Pitt, ten times the size of Fort Duquesne and built to house a thousand men.) Permanence seemed all the more likely insofar as the British commandants had encouraged white farmers to take up residence near their forts. In fact, the commanders had little choice but to welcome these settlers, for they had access to neither the money nor the means of transportation to feed the garrisons otherwise. Although these settlements were arguably only temporary expedients to be removed at the end of the war when the garrisons could safely be withdrawn, in fact they formed only the most visible components of a fast-spreading white settler population in the Transappalachian region. And those thousands of farmers and hunters were in turn attracting the attention of land speculators on both sides of the Atlantic—powerful men who sensed vast potential profits in the sale of western lands. Their ability to influence government policies toward the interior so far exceeded that of native groups that the Indians’ capacity to defend their interests dwindled to a single, terrible option: war.

Writing stand, c. 1760. Pennsylvania’s provincial assembly opened several trading posts in 1758-1759 in an effort to correct abuses in the Indian trade that had alienated the Delawares and other Indian nations. The former provincial officer Josiah Franklin Davenport (b. 1727), Benjamin Franklin’s nephew, managed the “province store” at Pittsburgh from 1761 to 1765. Josiah led a company of volunteer militia in the defense of Fort Pitt during the summer of 1763. (Courtesy of the Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania)

To the Indians these policies and the broken promises they bespoke were nothing short of betrayals, and a fundamental threat to their ability to carry on with the way of life they knew. Gift-giving and trade on generous terms had been integral to alliances between European and native peoples for more than a century and a half. To suspend the one and to restrict the other, and then to tolerate (and even invite) settlement on Indian lands, could only be understood as hostile acts. When British local commanders proved unwilling—because, in fact, they were unable—to respond to native protests, Indian leaders concluded that they would have to teach the British how to behave with proper respect for their allies and hosts. Of all the major nations in the northeast and the Great Lakes Basin, only the Iroquois held back, and even they were not unanimous in doing so. Despite Sir William Johnson’s influence with the League Council, the Seneca—historically the Iroquois nation most favorably disposed toward the French—showed a strong preference for joining the growing resistance movement.

In advocating war as a remedy for Britain’s affronts, native leaders were doing nothing new. Indian groups had always used force when necessary to bring erring partners to their senses, and to force them to reinstitute proper, respectful, and mutually beneficial trading relationships. One thing, however, had changed. In previous decades the French alliance had provided the framework for cooperation among most of the groups that found themselves distressed by Britain’s seeming arrogance and ill conduct. Now that the French were no longer able to function as a coordinating diplomatic influence, native groups used Neolin’s nativist prophecies to create an alliance system that was animated not by any human Father but by the Master of Life himself.

The Ottawa war chief Pontiac, an early and persuasive advocate of military action against the British, explicitly appealed to Neolin’s teachings in late April and early May 1763 when he convinced the leaders of the Potawatomi and Wyandot bands who lived near Fort Detroit to join him in attacking the British garrison there, but to spare the French farmers who lived outside the fort. Over the next weeks, as word spread of the attack on Detroit, similar councils took place near every British-held fort throughout the pays d’en haut. The resulting surprise attacks, conducted in rapid succession across a vast geographical range with such great effectiveness, stunned British commanders at all levels. They could only conclude that renegade French officers and missionaries were behind the rebellion. Nothing of the sort was true. Rather, the war that they mislabeled “Pontiac’s Rebellion” was a true pan-Indian movement, the first successful one (with the arguable exception of the 1680 Pueblo Revolt) in North American history.

Originating in the common grievances that Amherst’s policies had created among native peoples, the great Indian insurrection was a coordinated uprising in only the most general sense. Yet by any military measure it achieved extraordinary success from the very beginning. In less than two months from Pontiac’s May 9 attack on Detroit the western Indians had taken all but three British interior forts: Detroit, Pitt, and Niagara. The rest had been seized by force or guile, their garrisons annihilated or taken captive. Indian warriors then launched raids on the vulnerable frontiers of Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia, throwing settler populations into panic just as they had in 1755-1758. In desperation during June and July 1763, Sir Jeffery Amherst scraped together expeditionary forces from the remains of regiments that had been shattered by West Indian campaigning and tried to reinforce the garrison at Detroit, which was barely holding on, and to resupply Niagara and Fort Pitt, which were in better, but still perilous, condition. He instructed his field commanders to employ measures of extreme ruthlessness, including the killing of Indian prisoners. “We must,” he wrote, “Use Every Stratagem in our power to reduce them,” “their extirpation being the only security for our future safety.” Such was Amherst’s mood when, infamously, he approved the desperate measure that Fort Pitt’s commandant, Captain Simeon Ecuyer, had tried on June 24: taking advantage of a truce, Ecuyer had given the local chiefs a diplomatic present that included blankets and handkerchiefs that had recently been used by smallpox patients in the fort’s hospital.

There is no evidence that Amherst’s genocidal intentions and Ecuyer’s abominable act actually succeeded in spreading smallpox among the Shawnees and Delawares who besieged Fort Pitt, for smallpox was already endemic in both groups at the time. The intent, however, is more important than the result, for it indicates the extent to which native peoples had been dehumanized in the minds of Amherst and his beleaguered fellow officers. This level of Indian-hating can only be ascribed to what was now nearly a decade of intermittent warfare, and it was surely no more pronounced among the commanders of the British forces in America than in the white population of the colonies generally. Particularly in the frontier districts of Pennsylvania and Virginia most exposed to raids, the renewal of captive-taking and terror attacks only deepened the conviction, born of war, that the only good Indian was a dead one.

“Sketch of the Fort at Michilimackinac,” 1766. British forces occupied the stockaded French mission and village at Michilimackinac in 1761, following the fall of New France. Two years later a large group of Ojibwa and Sauk warriors, inspired by Pontiac’s attack on Detroit, used an ingenious stratagem to seize the fort. Playing an extended game of lacrosse outside the walls on the morning of June 2, 1763, the warriors chased a ball thrown into the fort’s interior through the open gate, taking weapons as they ran from women spectators who had hidden them beneath their blankets. Within minutes they killed or captured the garrison, taking control not only of the fort but also a large quantity of supplies, arms, and ammunition, without the loss of a single warrior. (William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan)

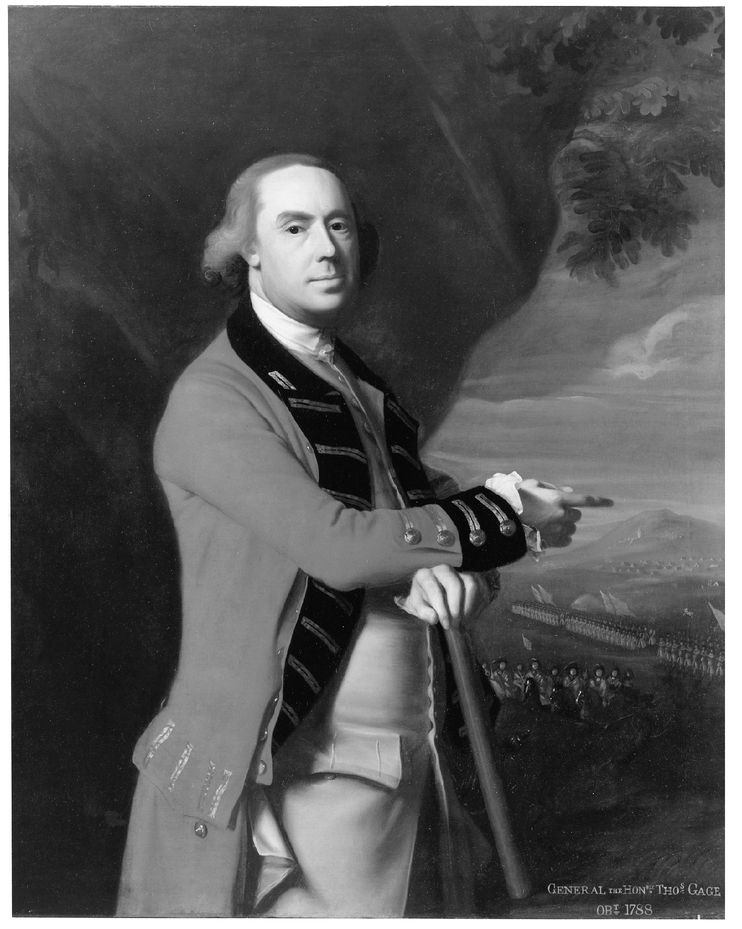

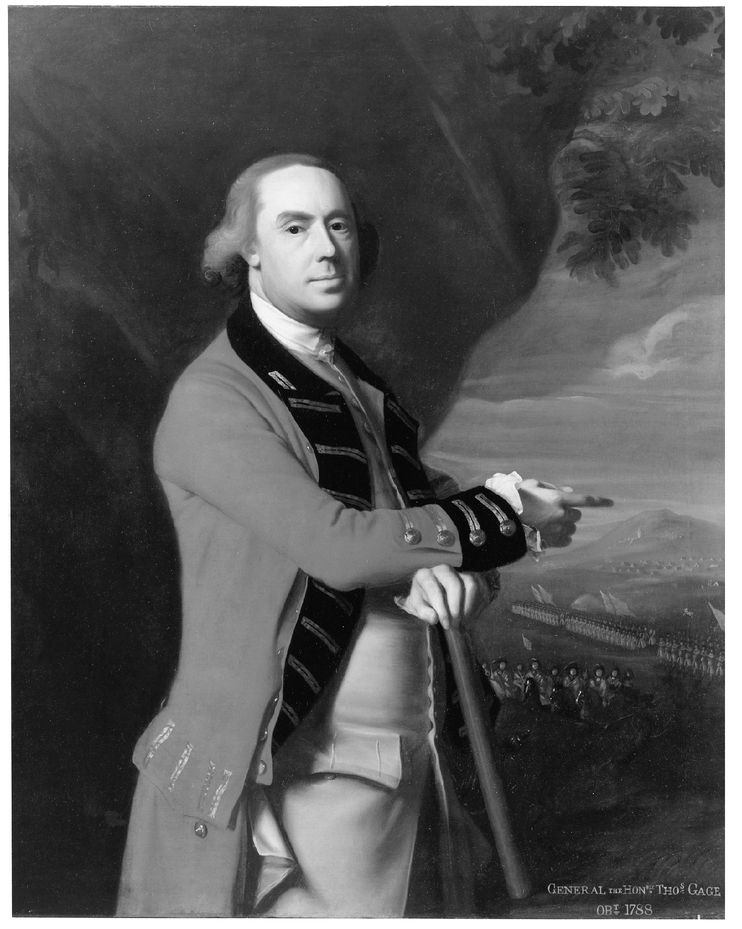

Once his initial, hysterical reaction to the Indian rebellion had passed, Amherst’s strategy for restoring order settled on the brutally simple solution of waiting for the warriors to run out of ammunition, then attacking their communities to destroy food supplies. Faced with starvation, the Indians would make peace on terms the empire would dictate. In the end, however, this was not to be, for the new Grenville ministry decided to recall Amherst from America, ostensibly for consultations on the state of the colonies. Sir Jeffery, who had previously begged for permission to return home to deal with pressing personal concerns (among others, his estate had fallen into disrepair and his wife had gone mad), was delighted to turn the office of commander in chief over to Major General Thomas Gage, the long-experienced, unimaginative officer who had been acting as military governor of Montreal. He sailed for Britain in mid-November 1763.

What Amherst did not know until he had arrived was that it was not a hero’s welcome that awaited him, but serious questioning about what had gone wrong in America. There would be no princely reward—no peerage, much less a Blenheim—to mark his services; the king merely remarked that while Sir Jeffery’s accomplishments were no doubt impressive, they “would not be lessened if he left the appreciating [of] them to others.” Amherst’s most important patrons could do nothing to help him: Pitt was in opposition with no real hope of returning to power, and the king’s uncle the duke of Cumberland, once captain-general of the British army, had suffered an incapacitating stroke. Sir William Johnson’s powerful friends and associates, on the other hand, had done their well-connected best to ensure that Amherst would be blamed for an insurrection in which at least four hundred regulars and two thousand colonists had been killed or taken captive, with no end in sight.

General Thomas Gage, by John Singleton Copley (1738-1815), c. 1768. Thomas Gage (c. 1719-1787) commanded the British advance guard at the Battle of the Monongahela, and served throughout the French and Indian War. He raised a regiment of light infantry trained in irregular tactics and married the New Jersey native Margaret Kemble in 1758. When Jeffery Amherst was recalled to England in 1763, Gage succeeded him as commander in chief of His Majesty’s forces in North America, a position he held until 1775. (Oil on canvas mounted on masonite, 50 x 39¾ in [127.0 x 101.0 cm], Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1977.14.45)

Back in America, Gage did his best to fulfill Amherst’s plans to end the insurrection in 1764. Militarily, the results were uneven, but in the end that did not matter, for it was not force but negotiation and concession that brought peace once more to the frontiers. In October 1763 the king issued a royal proclamation reaffirming the promises that had been made at the Treaty of Easton by formally prohibiting white settlement beyond the crest of the Appalachian Mountains. Those who still lived there were instructed “forthwith to remove themselves,” leaving the interior of the continent as a vast, unorganized Indian reservation, in which the sole representatives of royal authority would be the commandants of British forts. At a series of treaty talks begun in 1764, Sir William Johnson and his representatives built on the Proclamation of 1763 by offering to reinstitute the giving of diplomatic gifts and to permit an essentially unrestricted trade in ammunition and rum. Johnson asked that various Indian groups, in return, agree to return the captives they had taken. Given the role captives served in Indian families and communities, this was no small concession, and it took a great deal of time and negotiation to secure it. Ultimately, however, most native groups agreed, and rested content in the knowledge that the British, if arrogant and not particularly bright, were at least educable in the realities of power.

By late 1765 the empire’s relations with the Indians had at last stabilized. From Whitehall’s perspective, this resolution came not a moment too soon. Even as imperial authority had once more been established in the interior of North America, it was coming under even more severe challenges in the colonies along the eastern seaboard. From New Hampshire to Georgia, colonists who had recently exulted in their empire’s victory over France suddenly, inexplicably, seemed willing to launch an insurrection of their own. It would prove to be a rebellion of such scope and potential destructiveness that Pontiac’s War seemed in comparison but a minor bump in the road.

The Proclamation of 1763. Issued on October 7, 1763, this royal proclamation asserted British imperial control over newly won territories in North America even as it sought to reduce tensions with the Native Americans by prohibiting all white settlement beyond the Appalachian ridge and promising to open a regulated Indian trade in the interior. These measures effectively restated promises made in the 1758 Treaty of Easton; as before, they were essentially unenforceable, and widely ignored. (William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan)