IN PARIS, HELENE Dubrule, as head of marketing for Hermès’s perfumes—both those extant and those Ellena would be creating—was responsible most centrally for how the house’s perfumes would be sold.

One of the first meetings I sat in on at Hermès was, a bit quixotically, the most sensitive meeting possible. They’d only just started to get used to me. Dubrule ran the meeting. Its point was the elucidation of the broadest strategy for Parfums Hermès.

Hermès itself is oddly fragile. It is far more bothered by the difficult commercial environment in which perfume is sold than, for example, Ralph Lauren (whose perennial commercialness is robust) or Missoni (which can cruise cushioned by a certain Italian loyalism). Hermès is French, and thus it is brittle, difficult to change without breaking, a quality that counts among the greatest French weaknesses. This was what Dubrule was facing. That said, perfume poses a problem for any serious luxury house. Edith Touati, Hermès’s director of international marketing from 1984 to 1990, had faced the weird perfume problem, which boiled down to a question of brand control. During her tenure, she had opened boutiques all over the world, and, she said, the only product that made her uncomfortable was perfume, for one simple reason. The house’s silk ties, its burnished shoes, its shirts and saddles, its dinnerware and watches, all its products were sold in Hermès boutiques. All except the perfumes.

“It’s difficult to talk about Hermès fragrances,” Touati said in a practical, straightforward way. “Their products are sold only in their stores while their perfumes are sold in perfumeries: Saks, Sephora, Barneys, other people’s places, and then”—she grimaced—”the discount stores with fluorescent lighting that get hold of some bottles illegally and stack them on metal shelves next to aftershaves. C’est un produit Hermès qui est sorti de l’univers Hermès. Perfume is an Hermès product taken out of the Hermès universe. Which doesn’t always put it in a favorable position.” There are fourteen Hermès stores in the United States, thirty in France, and thirty-six in Japan, and each is an immaculate temple. But Hermès perfumes are sold in thousands of crappy little stores presided over by fat men with mustaches.

Touati recognized that all the houses could say the same thing—”Imagine Comme des Garçons in some pharmacie (drugstore)?” she said—but argued that Hermès has a stronger identity than almost any other house. “It’s a very coherent, elitist brand, and that is precisely the problem: Perfume is no longer an elitist product, and the distribution system is such that it’s sold in other people’s environments, which Hermès does not and cannot control. Perfume is thus quotidien, everyday.”

She paused, noted pointedly: “Everyone, every year, asks the same question: ‘Why is there no Vuitton perfume? Why doesn’t Vuitton jump in?’ The answer is obvious. It’s because there would then be Vuitton products in some store that’s going to treat them like any other product, store them on some shelf somewhere, and put them on sale at 50 percent off, and they’ll have no control over their own products. And this is a brand that never discounts any product, a brand as obsessed with control as one can be. And you really think Vuitton should do this?” She paused again, then said, “Non, je ne pense pas.” No, I don’t think so. “Clearly they don’t either.”

Dubrule was as conscious as anyone of what had made the List—as it is known in the industry—and what had not. The perfume industry is just as obssessed with the best-seller lineup as Hollywood is with the international box-office scores, and the executives and perfumers pore over the lists like shamans over runes, reading the signs, trying to divine trends. Dubrule knew the previous year’s lists—2003, the masculines and feminines (in an indication of how outmoded the assessments are, there is no list for the most interesting category of perfume, mixed scents)—but what was one supposed to glean from them?

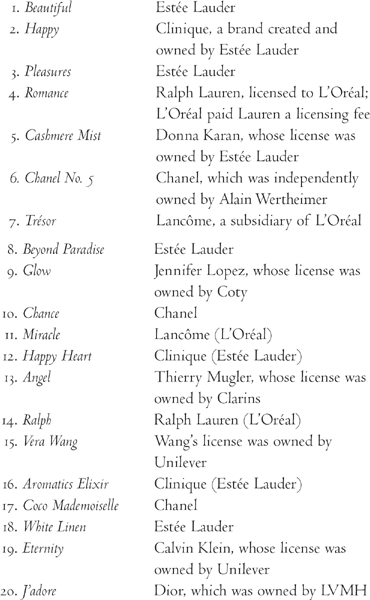

The bestselling feminines in the United States in 2003, when the U.S. fragrance industry was worth around $6 billion, were the following:

In other words, of the top twenty, Estée Lauder owned eight, L’Oréal owned four, and Chanel, three. Unilever owned two. Coty owned one, and LVMH owned one. This lineup had changed little since the previous year, 2002, when the top four had been Beautiful, Happy, Pleasures, Romance, all identical to the top four in 2003 and in the identical order. In fifth place was Chanel No. 5. Cashmere Mist had been seventh.

The List is made up of sales data from various sources, the sources change and are never complete, and the full picture is never entirely clear. This means that neither the Big Boys, who make the perfumes, nor the brands, such as Hermès, ever get total information. Still, the List is, generally, an accurate picture of the field. NPD is the company that collects U.S. industry sales data, organizes and analyzes it, and then sells it back to the industry. (Every player buys NPD’s products, and the bigger they are, the more data they buy.) As soon as the bar code on a box of perfume is swiped, it is automatically added to the NPD stats, which at the time covered around 85 percent of stores, though for complicated political reasons not Saks 5th Avenue, which meant that when Narciso Rodriguez’s eponymous scent became a big hit at Saks it didn’t appear on the List because it was a Saks exclusive. Until 2002, NPD didn’t cover Sephora, which made the List look very different after 2002.

NPD recorded that the best Hermès performer in 2003 in (and only in) U.S. department stores (NPD doesn’t collect data from, among others, Hermès boutiques) was 24 Faubourg at $613,945 for 6,513 units (bottles of perfume). As such, 24 Faubourg came in at number 217 on the List, nothing to write home about, to put it mildly. This was the year before Hermès took on Ellena.

In 2002, 24 Faubourg had been $451,027; in 2000, virtually nonexistent commercially—at number 301 on the List—at $7,430. Hermès was playing around the number 300 mark: In 2003, Calèche was number 293 ($164,758), Hiris was number 330, and Rouge Hermès was number 316. The Hugo Boss marketers wouldn’t have gotten out of bed for numbers like these, but on the other hand the Hugo Boss perfume creatives produce nerve gas. Hermès was doing slightly better with the fragrances it marketed to men: Bel Ami came in at number 164 with $105,318, Equipage was number 179 ($42,985), and Rocabar was number 177 ($55,306). (Notice that a men’s number 177 can be $55K, where a women’s number 293 comes in at $164K.)

Chanel No. 5 sales in 2003 were reputed to be around €180 million, “and,” said an executive at Chanel’s most direct rival, “this perfume is eighty years old! It’s unbelievable! It’s not a fragrance; it’s a goddamn cultural monument, like Coke. It’s the reference.”

Hermès’s numbers were nowhere near this. Dubrule discussed them. Everyone else discussed them too. I was having lunch in a restaurant on the place de Barcelone with a woman in a smart Chanel suit and red lacquer nails who had Dior’s and Kenzo’s and Issey Miyake’s numbers in her head, and when she could not recall those from Hermès, she put down her salad fork, picked up her cell phone, and “Didier,” she said breezily, “tu peux me chercher le chiffre d’affaires des parfums Hermès?” (Could he grab her Hermès’s grosses for its perfumes?) She ate a radish for a moment, gazing at the sky with the phone between an ear and a shoulder. Then he was back. “Oui,” she said, then “Cinquante-cinq millions d’euros dans la parfumerie,” she said, and then, “tandis que les gros revenues sont d’un milliard trois cents.” Hermès made €55 million annually in perfume on a €1.3 billion gross. “D’acc, merci.” She hung up, shrugging. “Ça participe à l’image.” The perfumes add to the image.

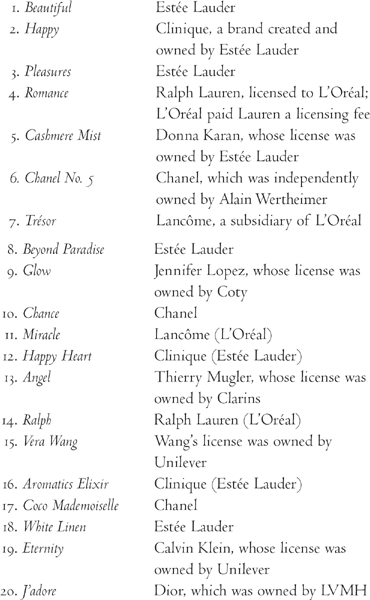

One thing about the List is that it’s quite different depending on the country. In 2003 Chanel No. 5 was number one in Great Britain, number three in Spain, number two in Italy and Germany, and number one in France. (It was also number one on the European list, due mostly to the huge weight—the sheer number of bottles rung up—that the French consumer gives the French list. In France, 170,000 bottles of perfume are sold every day.) Contrary to the U.S. lineup, the list of the 2003 bestselling feminines in France looked like this.

Of the top twenty, Chanel owned five, and so did LVMH. PPR and L’Oréal each owned two. Estée Lauder owned one, at the bottom, and its number one bestseller in the United States, Beautiful, didn’t even appear on the French list, nor its number three, Pleasures, nor its number eight, Beyond Paradise. Neither Vera Wang nor Glow made the list in France; nor did either Ralph Lauren’s bestseller or Donna Karan’s Cashmere Mist or the Calvin Klein. Even one of the French perfumes that made the U.S. list, Miracle, did not place in France. All in all, of the top twenty, twelve scents on the American list didn’t appear on the French list, all of them American; thirteen of the French best sellers didn’t appear on the U.S. list, and of those, twelve were French.

The number one scent in Germany was Jil Sander Sun, by a German designer, which appeared on none of the other lists. In Spain Anaïs Anaïs, Noa, and Emporio Armani made it; Noa showed up in no other countries. Jennifer Lopez’s Glow made the list in Germany (at number twenty) but not in Italy or Spain. Lauder, which completely dominated the American list, managed to get two in Spain —Pleasures and Happy—and four in Great Britain but none in Italy or Germany.

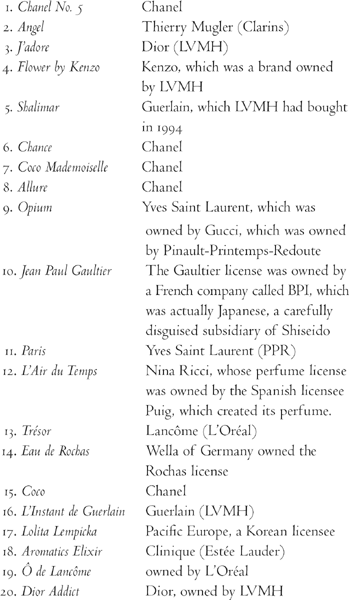

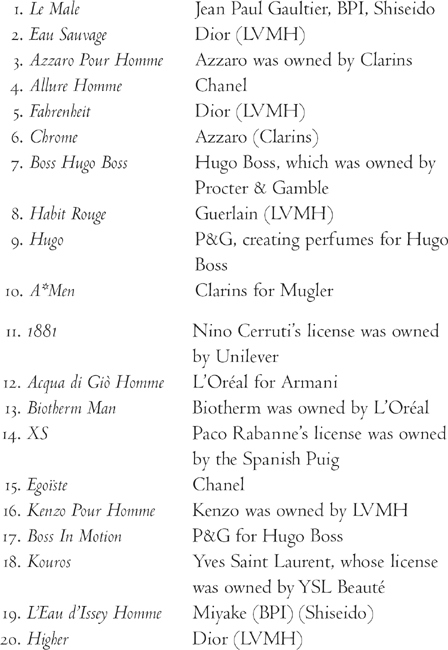

As for the masculines, the 2003 U.S. list looked like this.

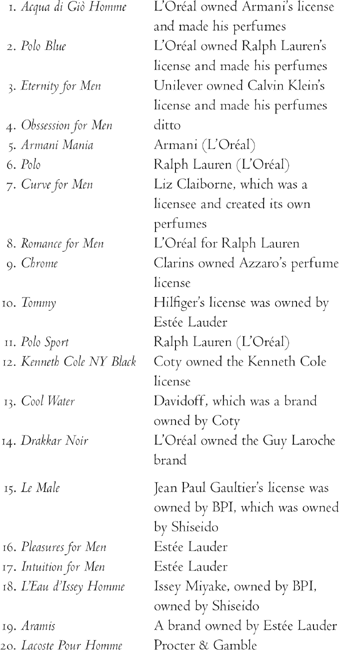

L’Oréal six, Lauder four, BPI two. LVMH, zero. It was the second year in a row at #1 for Acqua di Giò Homme, a juice that for L’Oréal, which had the Armani license, was essentially a license to print money. Other than American men having purchased enough insecticide to get Hugo from Boss, Aramis, and Chrome on the list and the appearance of Kenneth Cole (weed killer), the previous year revealed nothing except (1) there were no Hermès perfumes and (2) American men had, overall, bad taste. Interestingly, French men had even worse taste. The 2003 French masculines list looked like this:

Lauder zero. Procter & Gamble on the other hand had sold enough disinfectant to Frenchmen to give it three placings.

The feminine lists—particularly the French lists—represented a certain happy consensus on some quite decent perfumes: Jean Paul Gaultier and Paris are hands down gorgeous, it’s always nice to see L’Air du Temps, and Jennifer Lopez’s Glow is, in fact, a very well designed commercial perfume. Beyond Paradise is an admirably daring conceptual device that succeeds. J’adore shows what modern luxury smells like; Flower by Kenzo is a delightful contemporary floral. Coco’s coming in at fifteen showed that Frenchwomen could still wear a heavyweight French classic and L’Instant de Guerlain’s at sixteen that they could also understand a light luminous French modern. There were also a few slips. It is time to recognize that Trésor smells like celery, and not in a good way, and Eternity’s time has probably come and gone; Chance is, by Chanel’s standards, merely nice and not particularly interesting, innovative, or deep. That said, it was encouraging to see that perfumes with the exquisite youthful sophistication of Coco Mademoiselle, the daring of Angel, and the fullthroated design of White Linen and Shalimar could still top the charts and pull in the benjamins.

The List means financial reward, but it does not necessarily mean profit. Take Calice Becker’s J’adore, the blockbuster she created in 1999 for Dior. In just a few years, J’adore had topped a breathtaking €130 million, and apparently it has earned a quarter of a billion dollars—this is a single perfume—for Dior and is still hauling in grosses by the bucket. (It’s made money as well for Givaudan, the Big Boy that is Becker’s company and that produces J’adore’s juice for Dior: mixes the raw materials in the formula, manufactures the solution in alcohol at X percent, chills, filters, colors, and ships this juice directly to the filler, who bottles it. I was told that Givaudan has made on J’adore perhaps €15 million, which if it were true would give you an idea of the difference in markup from producer to brand and from brand to consumer, although I wouldn’t bet anything on this number.) What is certain, by contrast, is that the vast, infamous markups on perfume are exaggerated, not in specific but in ultimate terms. Specifically the margins, measured strictly on the cost of the juice in that bottle, are large. Scent makers like Givaudan generally put a margin of 3 or 4 on their formulae; that is, if they have a $10 RMC (raw material cost) per kilo for some given stuff, they’ll charge Lauder $40 per kilo for it, though I’ve heard of margins from 2 to 6, depending on the material, the scent maker, the brand, et cetera. (Incidentally, “multiple” and not “margin” is, to be technical, the correct word to use, “although,” as one industry guy responded when I asked him about it, “no one says ‘multiple.’ It’s like you have to misuse the language to show you’re an insider.” He headed right back to the money question, forcefully: “Listen, when you consider our massive R&D costs, ‘K? Our net profits are not all that glamorous.”)

Obviously when the brand (Dior, say) retails the raw materials to you, you’re paying the RMC plus Givaudan’s margin plus Dior’s margin plus Bloomingdale’s margin, but again—not all that glamorous: Dior’s overhead costs have become so great, and marketing, advertising, shipping, commissions, splits, kickbacks of various dismal kinds so significant, that in the end profits in the perfume industry come back toward what insurance companies tend to make. This is actually quite decent (healthy insurance companies clean up), but still, it is a tough, risky, brutal, expensive business, one proceeds into it well advised, and one survives in it through constant struggle. The executives at Dior and Givenchy and Armani have wonderful dinners at Per Se and Georges, but they also have sleepless nights.

When it works, it works like nothing else. Estée Lauder introduced Youth-Dew (made by IFF), and the perfume became the company’s engine. Business went from, roughly, $300 a week in some stores to $5,000, unheard of in 1953. By the time Leonard Lauder joined his mother’s company in 1958, total sales were about $800,000 a year, much of that from Youth-Dew.

Also, frankly, smell is so powerful that given half a chance it’s hard to resist taming that power. You pat a dog and then smell your hand to smell how much dog is left on your hand and what that dog smells like. It’s the most concrete information you’ll have all day.

When I asked Coty’s Carlos Timiraos how much a successful perfume makes, he said, “It depends on your definition of success. It takes a lot of money to make a fragrance work, and there can also be huge differences between grosses and profits. Industry profitability? Generally the investor’s risk is the same as stocks; you make about as much money as you would in the stock market. A good profit for a perfume is generally a return in the teens. And you virtually never make money in the first two years, sometimes not for three or four, although people are launching so many perfumes that a very few are now making a profit in the first year or two. And a lot of perfumes lose money; again, it’s very much like Hollywood. Studios can spend a hundred million producing and marketing a movie and make fifty million at the box office. Luckily a perfume has a longer life span than a movie and translates more easily outside the U.S. The superhits, one of the big ones, could on annual sales of a hundred million make between twenty or forty million in net profits in a year. These are the big established megabrands—it could never be a new brand—but it completely depends on many variables. And even a six-month-old megabrand launch will only make money three years down the road.”

The surefire formula for making a bestselling masculine seems simply to be mixing together enough dihydromyrcenol (laundry detergent) with the smell of metal garbage can to choke a horse, then topping that with the scent of cryogenically frozen citrus peel dusted with DDT and a whiff of recyled plastic. Chrome is fit, at a 10 percent dilution, for controlling weeds on your lawn. Aramis makes a fine garage floor sterilizer. But following a plan of simply pumping out some metallic doesn’t always work. All sorts of things that smelled of the effluent of arms manufacturing plants were put on the shelves every year and, for some reason, refused to sell. (The List, which is filled with things that smell like the effluent of arms manufacturing plants, doesn’t explain this mystery.)

Then there are the perfume industry’s odd and increasingly brutal economic practices, which have been rapidly changing—”deteriorating” is what you more or less universally hear.

The oddness starts with the amount of money the perfume brand has to give the Big Boy to develop their new perfume. The amount of money is: zero. The Big Boy pays for everything. Alexander McQueen and Bulgari and Stella McCartney pay literally nothing for the immense amount of time and very expensive work perfumers and the marketers who support them pour into their submissions. They pay nothing for the dozens if not hundreds of alterations that their creatives demand. (Week one: “Let’s do a slightly different gardenia angle.” Week four: “No, slightly more different.” Week eight: “Maybe not gardenia at all.” And then they add, “By the way, we’d like a really long sillage,” which might necessitate a completely different technical approach to the construction. The exhausted perfumer is thinking: Now you tell me.)

This means that the process is cruel to the people who actually make the scents. The Big Boys take all the risk and—at the same time—front all the costs. “The worst of both worlds!” as a French executive observed to me dourly. And now there’s core listing, where increasingly the licensees (L’Oréal, P&G, Lauder) force the scent makers to pay them a kickback of, say, half a million just to get themselves on the short list of the suppliers who’ll get a shot at doing the next Hilary Duff fragrance. You have to pay to play, and that’s just for the privilege of getting onto the field. So they cut costs upstream. IFF used to have six hundred materials suppliers, and they slashed the number by half, which meant that somewhere in Indonesia some small-time patchouli grower saw his market suddenly vanish.

The Big Boys’ only growth sector (completely unproductive) is their legal departments as LVMH must rely on Firmenich lawyers and Givaudan chemists to establish, and maintain with constant National Security Agency—level international surveillance, that some bureaucrat in Tokyo hasn’t suddenly outlawed Hedione, thus instantly making 90 percent of Dior’s perfumes the legal equivalent of poison sarin gas in Japan. (And speaking of the regulatory environment, it is only getting worse. I was traveling around Tunisia with a perfume materials marketer who was talking about the growing List of Banned Materials incredulously. “No more polycyclics! No more phthalate musks!”)

As much as everyone complains, no one changes things. “And how would we?” an American executive said to me. “Our clients, who benefit most from the current system, are exactly the people we can’t afford to piss off.” Simply because it’s the way it’s always been done, the industry is structured such that the Big Boys make their money on exactly one transaction and one only: supplying the finished juice. They cover every single cost until that moment, with no guarantee whatsoever of making a dime. It is an exceedingly bizarre structure, as those in it will be the first to tell you, and it has been this way from the start.

This means that the Big Boys are locked into a system of ferocious competition against each other. If you are a BPI or L’Oréal, an LVMH or Estée Lauder, the Big Boys fight for your brief, submitting any number of scents. Which (the Big Boys point out, privately) means a mess: L’Oréal winds up faced with, say, six different perfumers from six different Big Boys submitting maybe five submissions each, and the creatives are frozen before thirty different unfinished proposed scents. Paralysis.

To help them choose, just as the Hollywood studios do with their products, the marketing teams pay a lot of money to marketing consultants to focus-group the scents to death, thirty nice people from a suburb in New Jersey sitting in a room saying, “Nah, I don’t like it.” It reduces risk. But it usually produces mediocrities. Of course often these are mediocrities like Calvin Klein’s Euphoria, which haul in money hand over fist till Calvin Klein’s licensor is drowning in cash. (The focus groups, of course, cost more money.)

But all of this is nothing compared to the real cost, which is the launch. Now, finally, it is the brands—Coty, for example—that put in the money and assume the risk. Debuting a Coty perfume means Coty does media buys, publicity, samples, and training. One European man, a veteran of numerous perfumes, estimated to me that the minimum euros a house needs to invest in media for any correct launch is €2 million, although I was at a dinner party at which an American woman very powerful in the industry stated that it was more like €18 million or it wouldn’t work.

“Media is national,” said the veteran, “then the retailer pays for placement in the stores on a co-op basis. You can’t launch unless you’re in The New York Times, which is $70,000 a page, or maybe $125,000 a page depending on where you want your placement. Then there are all the other newspapers and magazines. In Europe we love the affichage, ads at bus stops and so on. In New York this is called guerrilla marketing and it’s looked down on, but you need it in Europe because the buzz is very important. For Diane von Furstenburg we put her perfume on the tops of all the taxis, and that was fun. In the three top cities in France affichage starts at $150,000 for one week and can rocket up from there to three million euros. And TV—forget it. And then there’s the GWP [gift with purchase] to budget for, the POS [point of sale] materials to pay for, the visuals, the displays, the posters, which is a huge cost, PLV [publicité sur le lieu de vente, the on-sales-site ads], and co-op.

“Co-op is the pretty notorious practice of the retailer paying half the cost of the ads in the store’s catalog. Say Hermès does a special co-op with Macy’s, an ad with them, in The New York Times. Macy’s says they’re sharing the Times ad, except that Macy’s has a huge discount with the Times because of volume, and Macy’s places the ad, not Hermès, so it actually costs them almost nothing. And then they say ‘And we’ll share the cost of our catalogs,’ which, Jesus, are a pure profit center for them, let’s be serious, you pay $30,000 for a page ad in Macy’s catalog, and it actually just brings them money by using Hermès’s name and image to sell Macy’s to the public, but Macy’s buying office is judged on their ability to sell this advertising space in the catalogs. They start with the top houses, the most prestigious, and go down till all their pages are sold.

“So you launch at Macy’s Herald Square, which is the number one surface in the world in terms of perfume sales, they sell you the Seventh Avenue outpost (and you pay for a new carpet to be put down the center of the aisle), and you hire twenty people to demo the perfume—spritz people as they walk by—and you have two or three people, whose entire salary you pay, working at the store to make sure everything goes right, and that’s half a million dollars for one week. And if you don’t do all this, then you’re not a Big Player, and your projections for the year are going to be less. And the sad thing is that the minute your seven days are up, everything you’ve paid for is ripped out, your new carpet is tossed, and the next fragrance invades the space.” He rolled his eyes. He’s been through it a thousand times, and every time is a gamble.

To make the retail game more complicated, there is what is known as the parallel market. As a French executive in Paris once expressed it to me, “The biggest, dirtiest secret is that you have to sell your products to yourself.” He explained that Chanel France makes the products and sells them to Chanel USA, which does the marketing and sells the products to Neiman Marcus or Saks. “That’s what’s official, OK?” But Chanel France also sells to Dubai, to a distributor supposed to promote the products in Dubai. And what if Dubai suddenly sells its products to some dirty stores on Fourteenth Street. “They shouldn’t,” he said with a shrug, “but of course they do. Chanel and certain other brands have trademark restriction, and they mark the boxes ‘Dubai’ or ‘Poland’ to identify where they were sold, and when you’re Chanel and you find your Dubai-destined perfume in some crummy West Fourteenth Street discounter you go back to Dubai and say ‘Fuck you, you’re a bunch of dirty Diverters,’ and shut them down.”

To control diverting, the Chanels of the world used to use lot numbers on the bottles. The Diverters ripped off the shinkwrap, opened the boxes, altered the numbers on the bottles, put the bottles back in the boxes, reshrinkwrapped them, and sent them out. Then the Chanels began writing the numbers in special invisible ink. But the Diverters bought black lights to find the codes and packages and either just cut them out or altered them with the same ink, then sold them on the black market. “And there’s new technology all the time,” another French executive told me. We were talking about this at Isetan, the huge department store in Tokyo, and one of his principal responsibilities was dealing with the problem in the Asian markets. “Now they also make a genetic thing you put in the juice itself, it floats around and you can read it simply by pointing a gunlike machine at the juice and pressing a button; Gaultier is very good at that, and they can’t get the stuff out of the juice, but they’ll find some way around it. Chanel is the best at protecting themselves,” he said. “LVMH is not especially good. If you take all the sales, 50 percent of perfumes are sold in these parallel markets. It helps Chanel France’s bottom line, but it hurts Chanel USA’s bottom line. Nowadays it’s such a common practice it’s become uncontrollable. And even the parallel market is in its worst state everywhere because heads of companies have to make their yearly numbers, and so at the end of the year they get desperate and start pouring product into the legitimate markets, which then overflow into the parallel market, which right now is actually flooded. But at the same time it’s a sign of success: What’s the point of dealing in these products if no one wants you? One time my boss came in and pumped his arm in the air and shouted, ‘Yes! We’re on the black market!’”

In fact, the distribution system is now so overloaded that retailers are requiring houses to take back what they haven’t sold, the discrepancy between “selling in”—what Hermès might sell to its distributors for placement in stores—and “selling out”—how much Hermès perfume clients actually bought. This is new.

Everyone wants a hit, a Flower by Kenzo or a Pleasures, but it is an expensive roll of the dice every time you try to launch one. There is one long-time protection that has grown up in response: The perfume industry’s accounting rivals Hollywood’s in ingenuity, and the LVMHs and Estée Lauders, with their subsidiaries, numerous brands, and vast spreadsheets, could work any numeric magic they wished. When you are a billionaire like Jean-Louis Dumas, Ronald Lauder, Bernard Arnault (head of LVMH), or Alain Wertheimer (owner of Chanel), you are careful to blur or mask any numbers going out to the public that might reveal a flaw. You have a compelling interest in doing so: These are empires resting on nothing but image. (Naturally it is slightly easier to get the good sales figures, but no one trusts those, either.) I have been given numbers by CEOs so ridiculous I would never repeat them. One president gave me figures on his rival, Chanel. Are they accurate? Who knows. The company is privately owned, and Chanel numbers are more masked than any others.

The careful masking is, of course, the way of dealing with the flops. “You can’t always tell a flop,” a French perfumer said to me, “and no one can find out exactly how much a perfume lost because they consolidate their figures, although,” he added, “everyone whispers guesses.” The strategy, he said, is that the brand spends in the first year on ads what it expects to gross in that year on the perfume. “There are some that everyone considers clear successes: Acqua di Giò Pour Homme, which Jacques Cavalier of Firmenich did. I hate it, but it’s genius. Fresh. Clean. Crisp. And it smells, a huge diffusion, massive volume. It’s a work of art. It’s magic. It’s up to €150 million total worldwide and was number one on the lists for five years. Le Male by Francis Kurkdjian is a huge hit. Cool Water by Pierre Bourdon, hit, Pleasures by Alberto Morillas and Annie Buzantian, hit, Polo Blue”—by Carlos Benaïm, Christophe Laudamiel, Laurent Bruyère, and Pierre Wargnye; perfumes are increasingly resembling Hollywood screenplays-by-committee—”hit, both Obsessions.

“Of course, you never know how much ad money they’ve poured into them. Well, some you just know. Did Lauder spend a hundred-twenty million in advertising for Beyond Paradise, or did they spend two hundred? I remember it as two hundred. Chanel’s Egoïste I heard is a flop given the amount they spent on advertising. Higher for Men by Dior? No one will give you figures. Champs Elysées by Guerlain is one of the paradigmatic, legendary disasters. Alexander McQueen is a huge flop. Some of them you just have to assume. Glamourous by Ralph Lauren? It’s not even listed! Christian Lacroix’s C’est La Vie was a huge flop because they launched, expensively, right after launching the haute couture house and LVMH thought he was going to do so well, and it didn’t. cK Be tanked in the U.S. Armani’s Giò by Françoise Caron has a beautiful tuberose note and was a huge flop. Spellbound by Estée Lauder was a huge flop, a spicy clove, and Nu and M7 by YSL were disasters.”

Guerlain’s Mahora “was probably the biggest flop I’ve ever seen,” one executive told me. He sighed. “You work like a dog, you get it on the shelf, you spend millions in advertising, and you wind up destroying tons of product in the factory.”

Everyone wanted to make the List. It was only natural. The question was how.

Dubrule and Gautier were, naturally, conscious of all the variables. They were also facing a growth rate in perfume sales of about 3 percent a year, which was anemic. It meant (everyone knew this) that any growth would come from pillaging the competition. It was brutal, and getting more brutal to a great degree because the industry had shifted to a new, aggressive, policy of developing fragrances that would appeal to the maximum number of people, which meant fragrances offering no resistance—sweet, coy things that didn’t just sleep with you on the first date but in the first ten seconds. The problem was that these scents were like Roman candles, a swift, awesome rise in sale (boosted by all your marketing expenditures), fifteen minutes of fame, and a swift crash as the next one got shoved onto the market. You generated large volume from “global appeal” and sudden death because each of them smelled exactly like the other. Why shouldn’t the client jump from launch to launch? Banality.

The second problem from Dubrule and Gautier’s perspective was that they were—oh yes—in the luxury business. That meant exclusivity. But the industry guru Yves de Chiris had been observing that everyone was acting like mass marketers. The fragrance problem was that the client couldn’t “reference” the truly original perfume, and what consumers couldn’t reference worried them, and what worried them was not commercial. Consumers claimed they liked original fragrances, but they got out their credit cards for the familiar.

De Chiris had a response, which was Thierry Mugler’s Angel. The scent was created by the perfumer Olivier Cresp, with de Chiris serving as one of the artistic consultants. The secret of Angel’s formula is a juxtaposition of two diabetic-shock-inducing sweet scents, marzipan (created with a synthetic molecule called coumarin) and cotton candy (the molecule ethyl maltol; this is the molecule you’re actually tasting when you eat cotton candy). Alone, this would be a tooth-rotting confection, but Cresp threw in a huge dose of natural patchouli, a grasslike plant grown principally in Indonesia, and its strange strong green/organic smell cuts through and freezes the sweetness “like,” de Chiris put it nicely, “crushed ice in Grand Marnier.”

Angel failed for two years—consumers found it incredibly divisive, pure love/hate. The house refused to drop it. Then it started to build. Then it exploded to become one of the best-selling perfumes of all time, and it is still on the top of the List. (Incidentally, Angel’s secret is more or less identical to Coca-Cola’s secret: Coke’s flavor comes from an overdosed sugar juxtaposed on a superacid taste.)

But the secret of Angel’s commercial success, de Chiris argued convincingly, was exactly this divisiveness. Only 3 percent of consumers would touch it. But those 3 percent were complete fanatics, enough to put the thing repeatedly in the top ten. So here was another model to think about: Go narrow and deep, proposed de Chiris, rather than wide and shallow. Which was another way, you could argue, of keeping perfume luxury: innovative, edgy, and not for everyone.

Gautier and Dubrule were aware of the strategy used so successfully with Angel, and they were in the midst of their own tactical defining of “Hermès perfume.” “When I arrived at Hermès,” Gautier told me, “we were going in all sorts of directions and were not as strong and coherent as we could be. So I took us in a direction completely different from the rest of perfumery and the rest of marketing.” Gautier was given to repeating, with the conviction of a mantra, that the error the luxury houses made was to do marketing for grande consommation, which essentially consisted of analyzing a demand and then creating a product that, one hoped, anticipated it. She was not that. She was Hermès, and Hermès was luxury, and luxury’s logic turned that theory upside down by starting with l’offre, an offer that would create a desire, and a demand. “It’s the opposite of marketing,” stated Gautier simply, with the assurance of an economics professor.

Dubrule’s comment was that in true luxury, one worked with artists, creators on whom one placed few constraints. One worked from an artistic vision, not (she said it with only slightly less disdain than did Gautier) from market studies. Which she had done; she had a business degree from one of the best business schools in France, thank you, and she knew perfectly well how the focus groups and so on worked. But to her—and to Gautier, who stated it adamantly—luxury meant an if-you-build-it-they-will-come strategy. Luxury, to Gautier, was proposé.

This was the subject of the meeting I sat in on.

We sat at the round table in Dubrule’s office, a long, clean, practical workroom with her desk at the far end by the window and the round meeting table and whiteboard at the other. They talked, and I took notes on my computer. Dubrule slashed arrows and arced big circles of emphasis around words on tablets of paper that represented the various Hermès perfumes. By prior agreement between myself and The New Yorker, on the one hand, and Hermès, on the other—we’d established some logical ground rules regarding the disposition of industrial proprietary information and Hermès trade secrets I would learn in my reporting—I can write about none of the details, but the general question before them was, when they considered all the above variables, How were they to place Hermès perfumes in the global market? The overall thrust, which Dubrule laid out, was that she and Gautier had decided on a three-pronged approach.

On the highest level would be the Hermèssences collection, superexpensive, superluxurious fragrances. The Hermèssences were scheduled to launch in October 2004. Ellena was hard at work on them. The house was going to start the collection with four scents—Rose Ikebana, Vetiver Tonka, Poivre Samarcande, and Ambre Narguilé—and add to it, one by one, every few years. Dubrule described their concept as being like the experience of dining with Pierre Gagnaire, Guy Savoy, Marc Verra, “great French chefs who are going to search out unexpected contrasts. We will,” she added with emphasis, “be able to use some very Hermès materials.” By this she meant expensive; the fragrances would thus be much more expensive than all the others on the market. The culinary description she meant as metaphor, though Ellena was creating one called Ambre Narguilé that would, when he was finished with it, smell—gorgeously, exquisitely—of cool, freshly sliced apples wrapped in leaves of blond tobacco drizzled with caramel, cinnamon, banana, and rum. This collection would only ever be sold in Hermès stores; these Hermès products would, significantly, never be sortis de leur univers—taken out of Hermès’s world. Below this price point would be the fundamental collection, Calèche, Rouge, and Hiris; the Jardins collection would be at a very slightly lower price point than Calèche and equal to that of Eau des Merveilles. Gautier was talking darkly about Hermès’s prices in the United States. She would have to raise them about 15 to 20 percent to compensate for the decaying dollar.

And that was the plan.