Figure 2-1: The whole (semibreve) note has a head; the quarter (crotchet) note has a head and stem; and the eighth (quaver) note has a head, stem, and flag.

Chapter 2

Determining What Notes Are Worth

In This Chapter

Understanding rhythm, beat, and tempo

Understanding rhythm, beat, and tempo

Reviewing notes and note values

Reviewing notes and note values

Counting (and clapping) out different notes

Counting (and clapping) out different notes

Getting to know ties and dotted notes

Getting to know ties and dotted notes

Combining note values and counting them out

Combining note values and counting them out

Just about everyone has taken some sort of music lessons, either formal paid lessons from a local piano teacher or at the very least the state-mandated rudimentary music classes offered in public school. Either way, we’re sure you’ve been asked at some point to knock out a beat, if only by clapping your hands.

Maybe the music lesson seemed pretty pointless at the time or served only as a great excuse to bop your grade-school neighbor on the head. However, counting out a beat is exactly where you have to start with music. Without a discernible beat, you have nothing to dance or nod your head to. Although all the other parts of music (pitch, melody, harmony, and so on) are pretty darned important, without beat, you don’t really have a song.

In this chapter, we provide you with a solid introduction to the basics of counting notes and discovering a song’s rhythm, beat, and tempo.

Note: You may notice in this chapter that we’ve given two different names for the notes mentioned — for example, quarter (crotchet) note. The first name (quarter) is the common U.S. name for the note, and the second name (crotchet) is the common U.K. name for the same note. The U.K. names are also used in medieval music and in some classical circles. After Chapter 3, we only use the U.S. common names for the notes, because the U.S. usage is more universally standard.

Meeting the Beat

A beat is a pulsation that divides time into equal lengths. A ticking clock is a good example. Every minute, the second hand ticks 60 times, and each one of those ticks is a beat. If you speed up or slow down the second hand, you’re changing the tempo of the beat. Notes in music tell you what to play during each of those ticks. In other words, the notes tell you how long and how often to play a certain musical pitch — the low or high sound a specific note makes — within the beat.

When you think of the word note as associated with music, you may think of a sound. However, in music, one of the main uses for notes is to explain exactly how long a specific pitch should be held by the voice or an instrument. The note value, indicated by the size and shape of the note, determines this length. Together with the preceding three features, the note value determines what kind of rhythm the resulting piece of music will have. It determines whether the song will run along very quickly and cheerfully, will crawl along slowly and somberly, or will progress in some other way.

When figuring out how to follow the beat, rhythm sticks (fat, cylindrical hard wood instruments) come in real handy. So do drum sticks. If you’ve got a pair, grab ’em. If you don’t, clapping or smacking your hand against bongos or your desktop works just as well.

Recognizing Notes and Note Values

If you think of music as a language, then notes are like letters of the alphabet — they’re that basic to the construction of a piece of music. Studying how note values fit against each other in a piece of sheet music is as important as knowing musical pitches because if you change the note values, you end up with completely different music. In fact, when musicians talk about performing a piece of music “in the style of” Bach, Beethoven, or Philip Glass, they’re talking as much about using the rhythm structure and pace characteristics of that particular composer’s music as much as any particular chord progressions or melodic choices.

Examining the notes and their components

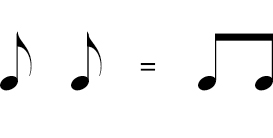

Notes are made of up to three specific components: note head, stem, and flag (see Figure 2-1).

Head: The head is the round part of a note. Every note has one.

Head: The head is the round part of a note. Every note has one.

Stem: The stem is the vertical line attached to the note head. Eighth (quaver) notes, quarter (crotchet) notes, and half (minim) notes all have stems.

Stem: The stem is the vertical line attached to the note head. Eighth (quaver) notes, quarter (crotchet) notes, and half (minim) notes all have stems.

Flag: The flag is the little line that comes off the top or bottom of the note stem. Eighth (quaver) notes and shorter notes have flags.

Flag: The flag is the little line that comes off the top or bottom of the note stem. Eighth (quaver) notes and shorter notes have flags.

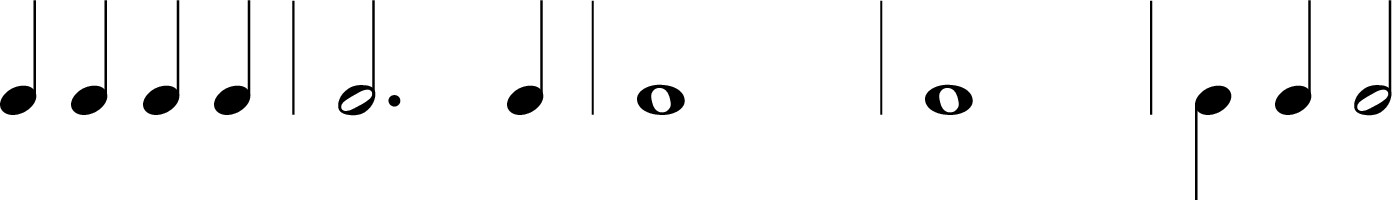

Instead of each note getting a flag, notes with flags can also be connected to each other with a beam, which is just a cleaner-looking incarnation of the flag. For example, Figure 2-2 shows how two eighth (quaver) notes can be written as each having a flag, or as connected by a beam.

Figure 2-2: You can write eighth (quaver) notes with individual flags, or you can connect them with a beam.

Figure 2-3 shows four sixteenth (semiquaver) notes with flags grouped three separate ways: individually, in two pairs connected by a double beam, and all connected by one double beam. It doesn’t matter which way you write them; they sound the same when played.

Figure 2-3: These three groups of sixteenth (semiquaver) notes, written in three different ways, all sound alike when played.

Likewise, you can write eight thirty-second (demisemiquaver) notes in either of the ways shown in Figure 2-4. Notice that these notes get three flags (or three beams). Using beams instead of individual flags on notes is simply a case of trying to clean up an otherwise messy-looking piece of musical notation. Beams help musical performers by allowing them to see where the larger beats are. Instead of seeing sixteen disconnected sixteenth (semiquaver) notes, it’s helpful for a performer to see four groups of four sixteenths (semiquavers) connected by a beam.

Figure 2-4: Like eighth (quaver) notes and sixteenth (semiquaver) notes, you can write thirty-second (demisemiquaver) notes separately or “beamed” together.

Looking at note values

As you may remember from school or music lessons, each note has its own note value. Before we go into detail on each kind of note, have a look at Figure 2-5, which shows most of the kinds of notes you’ll encounter in music arranged so their values add up the same in each row. At the top is the whole (semibreve) note, below that half (minim) notes, then quarter (crotchet) notes, eighth (quaver) notes, and finally sixteenth (semiquaver) notes on the bottom. Each level of the “tree of notes” is equal to the others. The value of a half (minim) note, for example, is half of a whole (semibreve) note, and the value of a quarter (crotchet) note is a quarter of a whole (semibreve) note.

Depending on the time signature of the piece of music (see Chapter 4), the note value that’s equal to one beat changes. In the most common time signature, 4/4 time, also called common time, a whole (semibreve) note is held for four beats, a half (minim) note is held for two, and a quarter (crotchet) note lasts one beat. An eighth (quaver) note lasts half a beat, and a sixteenth (semiquaver) note lasts just a quarter of a beat in 4/4 time.

Figure 2-5: Each level of this tree of notes lasts as many beats as every other level.

Whole (Semibreve) Notes

The whole note (called a semibreve note in the U.K.) lasts the longest of all the notes. Figure 2-6 shows what it looks like.

Figure 2-6: A whole (semibreve) note is a hollow oval.

In 4/4 time, a whole (semibreve) note lasts for an entire four beats (see Chapter 4 for more on time signatures). For four whole beats (semibreves), you don’t have to do anything with that one note except play and hold it. That’s it.

Usually, when you count note values, you clap or tap on the note and say aloud the remaining beats. You count the beats of whole (semibreve) notes like the ones shown in Figure 2-7, like this:

CLAP two three four CLAP two three four CLAP two three four

“CLAP” means you clap your hands, and “two three four” is what you say out loud as the note is held for four beats.

Figure 2-7: When you see three whole (semibreve) notes in a row, each one gets its own “four-count.”

Even better for the worn-out musician is coming across a double whole (breve) note. You don’t see them a whole heck of a lot, but when you do, they look like Figure 2-8, and they’re generally used in slow-moving processional music or in medieval music. When you see a double whole (breve) note, you have to hold the note for an entire eight counts, like so:

CLAP two three four five six seven eight

Figure 2-8: Hold a double whole (breve) note for eight counts.

You can also show a note that lasts for eight counts by tying together two whole (semibreve) notes. We discuss ties later in this chapter.

Half (Minim) Notes

It’s simple logic what comes after whole (semibreve) notes in value — a half (minim) note, of course. You hold a half (minim) note for half as long as you would a whole (semibreve) note. Half (minim) notes look like the notes in Figure 2-9. When you count out the half (minim) notes in Figure 2-9, it sounds like this:

CLAP two CLAP two CLAP two

Figure 2-9: Hold a half (minim) note for half as long as a whole (semibreve) note.

You could have a whole (semibreve) note followed by two half (minim) notes, as shown in Figure 2-10. In that case, you count out the three notes as follows:

CLAP two three four CLAP two CLAP two

Figure 2-10: A whole (semibreve) note followed by two half (minim) notes.

Quarter (Crotchet) Notes

Divide a whole (semibreve) note, which is worth four beats, by four, and you get a quarter (crotchet) note with a note value of one beat. Quarter (crotchet) notes look like half (minim) notes except that the note head is completely filled in, as shown in Figure 2-11. Four quarter (crotchet) notes are counted out like this:

CLAP CLAP CLAP CLAP

Figure 2-11: These four quarter (crotchet) notes get one beat apiece.

Suppose you replace one of the quarter (crotchet) notes with a whole (semibreve) note and one with a half (minim) note, as shown in Figure 2-12. In that case, you count out the notes like this:

CLAP two three four CLAP CLAP CLAP two

Figure 2-12: A mixture of whole (semibreve), half (minim), and quarter (crotchet) notes is getting closer to what you find in music.

Eighth (Quaver) Notes and Beyond

When sheet music includes eighth (quaver) notes and beyond, it really starts to look a little intimidating. Usually, just one or two clusters of eighth (quaver) notes in a piece of musical notation isn’t enough to frighten the average beginning student, but when that same student opens to a page that’s littered with eighth (quaver) notes, sixteenth (semiquaver) notes, or thirty-second (semidemiquaver) notes, she just knows she has some work ahead of her. Why? Because usually these notes are fast.

An eighth (quaver) note, shown in Figure 2-13, has a value of half of a quarter (crotchet) note. Eight eighth (quaver) notes last as long as one whole (semibreve) note, which means an eighth (quaver) note lasts half a beat (in 4/4, or common, time).

Figure 2-13: You hold an eighth (quaver) note for one-eighth as long as a whole (semibreve) note.

How can you have half a beat? Easy. Tap your toe for the beat and clap your hands twice for every toe tap.

CLAP-CLAP CLAP-CLAP CLAP-CLAP CLAP-CLAP

Or you can count it out as follows:

ONE-and TWO-and THREE-and FOUR-and

The numbers represent four beats, and the “ands” are the half beats.

Just think of each tick of a metronome as an eighth (quaver) note instead of a quarter (crotchet) note. That means a quarter (quaver) note is now two ticks, a half (minim) note is four ticks, and a whole (semibreve) note lasts eight ticks.

Similarly, if you have a piece of sheet music with sixteenth (semiquaver) notes, each sixteenth (semiquaver) note can equal one metronome tick, an eighth (quaver) note two ticks, a quarter (crotchet) note four ticks, a half (minim) note eight ticks, and a whole (semibreve) note can equal sixteen ticks.

A sixteenth (semiquaver) note has a note value of one quarter of a quarter (crotchet) note, which means it lasts one-sixteenth as long as a whole (semibreve) note. A sixteenth (semiquaver) note looks like the note in Figure 2-14.

Figure 2-14: You hold a sixteenth (semiquaver) note for half as long as an eighth (quaver) note.

If you have a piece of sheet music with thirty-second (demisemiquaver) notes, as shown in Figure 2-15, remember that a thirty-second (demisemiquaver) note equals one metronome tick, a sixteenth (semiquaver) note equals two, an eighth (quaver) note equals four, a quarter (crotchet) note equals eight, a half (minim) note equals sixteen, and a whole (semibreve) note equals thirty-two ticks.

Figure 2-15: You hold a thirty-second (demisemiquaver) note for half as long as a sixteenth (semiquaver) note.

Extending Notes with Dots and Ties

Sometimes you want to add to the value of a note. You have two main ways to extend a note’s value in written music: dots and ties. I explain each in the following sections.

Using dots to increase a note’s value

Occasionally, you’ll come across a note followed by a small dot, called an augmentation dot. This dot indicates that the note’s value is increased by one half of its original value. The most common use of the dotted note is when a half (minim) note is made to last three quarter (crotchet) note beats instead of two, as shown in Figure 2-16. Another way to think about dots is that they make a note equal to three of the next shorter value instead of two.

Figure 2-16: You hold a dotted half (dotted minim) note for an additional one-half as long as a regular half (minim) note.

Less common, but still applicable here, is the dotted whole (dotted semibreve) note. This dotted note means the whole (semibreve) note’s value is increased from four beats to six beats.

Adding notes together with ties

Another way to increase the value of a note is by tying it to another note, as Figure 2-17 shows. Ties connect notes of the same pitch together to create one sustained note instead of two separate ones. When you see a tie, simply add the notes together. For example, a quarter (crotchet) note tied to another quarter (crotchet) note equals one note held for two beats:

CLAP-two!

Figure 2-17: Two quarter (crotchet) notes tied together equal a half (minim) note.

Mixing All the Note Values Together

You won’t encounter many pieces of music that are composed entirely of one kind of note, so you need to practice working with a variety of note values.

The four exercises shown in Figures 2-18 through 2-21 can help make a beat stick in your head and make each kind of note automatically register its value in your brain. Each exercise contains five groups (or measures) of four beats each. The measures are notated with vertical lines, called barlines, that are explained more in Chapter 4.

Exercise 1

CLAP CLAP CLAP CLAP | CLAP two three CLAP | CLAP two three four | CLAP two three four | CLAP CLAP CLAP four

Figure 2-18: Exercise 1.

Exercise 2

CLAP two three four | CLAP two three four | CLAP CLAP three CLAP | CLAP two CLAP four | CLAP two three four

Figure 2-19: Exercise 2.

Exercise 3

CLAP CLAP-CLAP CLAP four | CLAP two three four | CLAP two three CLAP | CLAP-CLAP CLAP three four | CLAP two CLAP four

Figure 2-20: Exercise 3.

Exercise 4

CLAP two CLAP four | CLAP two three CLAP | CLAP two three four | one CLAP three four | CLAP two three four

Figure 2-21: Exercise 4.

Everything around you has a rhythm to it, including you. In music, the

Everything around you has a rhythm to it, including you. In music, the  Perhaps the easiest way to practice working with a steady beat is to buy a metronome. They’re pretty cheap, and even a crummy one should last you for years. The beauty of a metronome is that you can set it to a wide range of tempos, from very, very slow to hummingbird fast. If you’re using a metronome to practice — especially if you’re reading from a piece of sheet music — you can set the beat to whatever speed you’re comfortable with and gradually speed it up to the composer’s intended speed when you’ve figured out the pacing of the song.

Perhaps the easiest way to practice working with a steady beat is to buy a metronome. They’re pretty cheap, and even a crummy one should last you for years. The beauty of a metronome is that you can set it to a wide range of tempos, from very, very slow to hummingbird fast. If you’re using a metronome to practice — especially if you’re reading from a piece of sheet music — you can set the beat to whatever speed you’re comfortable with and gradually speed it up to the composer’s intended speed when you’ve figured out the pacing of the song. If you see two dots behind the note — called a

If you see two dots behind the note — called a