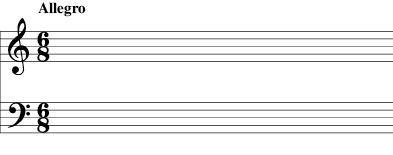

Figure 15-1: Allegro means the music would be played at a brisk pace.

Chapter 15

Creating Varied Sound through Tempo and Dynamics

In This Chapter

Keeping time with tempo

Keeping time with tempo

Controlling loudness with dynamics

Controlling loudness with dynamics

Everybody knows that making good music is about more than just stringing a collection of notes together. Music is just as much about communication as it is about making sounds. And in order to really communicate to your audience, you need to grab their attention, inspire them, and wring some sort of emotional response out of them.

Tempo (speed) and dynamics (volume) are two tools you can use to turn those carefully metered notes on sheet music into the elegant promenade of Liszt’s Hungarian Rhapsody No. 2, the sweeping exuberance of Chopin’s études, or, in a more modern context, the slow creepiness of Nick Cave’s “Red Right Hand.”

Tempo and dynamics are the markings in a musical sentence that tell you whether you’re supposed to feel angry or happy or sad when you play a piece of music. These markings help a performer tell the composer’s story to the audience. In this chapter, we help you get familiar with both concepts and their accompanying notation.

Taking the Tempo of Music

Tempo means “time,” and when you hear people talk about the tempo of a musical piece, they’re referring to the speed at which the music progresses. The point of tempo isn’t necessarily how quickly or slowly you can play a musical piece, however. Tempo sets the basic mood of a piece of music. Music that’s played very, very slowly, or grave, can impart a feeling of extreme somberness, whereas music played very, very quickly, or prestissimo, can seem maniacally happy and bright. (We explain these Italian terms, along with others, later in this section.)

Prior to the 17th century, composers had no real control over how their transcribed music would be performed by others, especially by those who had never heard the pieces performed by their creator. It was only in the 1600s that composers started using tempo (and dynamic) markings in sheet music. The following sections explain how tempo got its start and how it’s used in music today.

Establishing a universal tempo: The minim

The first person to write a serious book about tempo and timing in music was the French philosopher and mathematician Marin Mersenne. From an early age, Mersenne was obsessed with the mathematics and rhythms that governed daily life — such as the heartbeats of mammals, the hoof beats of horses, and the wing flaps of various species of birds. This obsession led to his interest in the field of music theory, which was still in its infancy at the time. With the 1636 release of his book, Harmonie universelle, Mersenne introduced the concept of a universal music tempo, called the minim (named after his religious order), which was equal to the beat of the human heart, around 70 to 75 beats per minute (bpm). Furthermore, Mersenne introduced the idea of splitting his minim into smaller units so that composers could begin adding more detail to their written music.

Mersenne’s minim was greeted with open arms by the musical community. Since the introduction of written music a few hundred years before, composers had been trying to find some way to accurately reproduce the timing needed for other musicians to properly perform their written works. Musicians loved the concept because having a common beat unit to practice with made it easier for individual musicians to play the growing canon of musical standards with complete strangers.

Keeping steady time with a metronome

Despite what you may have gathered from horror movies such as Dario Argento’s Two Evil Eyes and a number of Alfred Hitchcock’s films, that pyramid-shaped ticking box does have a purpose besides turning human beings into mindless zombies.

The metronome was first invented in 1696 by the French musician and inventor Étienne Loulié. His first prototype consisted of a simple weighted pendulum and was called a cronométre. The problem with Loulié’s invention, though, was that in order to work with beats as slow as 40 to 60 bpm, the device had to be at least 6 feet tall.

It wasn’t until more than 100 years later that two German tinkerers, Dietrich Nikolaus Winkel and Johann Nepomuk Maelzel, worked independently to produce the spring-loaded design that’s the basis for analog (non-electronic) metronomes today. Maelzel was the first to slap a patent on the finished product, and as a result, his initial is attached to the standard tempo sign, MM=120. MM is short for Maelzel’s metronome, and the 120 means that 120 bpm, or 120 quarter notes, should be played in the piece.

Like the concept of the minim (refer to the previous section), the metronome was warmly received by musicians and composers alike. From then on, when composers wrote a piece of music, they could give musicians an exact number of beats per minute to be played. The metronomic markings were written over the staff so that musicians would know what to calibrate their metronomes to. For example, quarter note=96, or MM=96, means that 96 quarter notes should be played per minute in a given song. These markings are still used today for setting mostly electronic metronomes, particularly for classical and avant-garde compositions that require precise timing.

Translating tempo notation

Although the metronome was the perfect invention for control freaks like Beethoven, most composers were happy to instead use the growing voc-abulary of tempo notation to generally describe the pace of a song. Even today, composers still use the same Italian words to describe tempo and pace in music. These words are in Italian simply because when these phrases came into use (1600–1750), the bulk of European music came from Italian composers.

Table 15-1 lists some of the most standard tempo notations in Western music, usually found written above the time signature at the beginning of a piece of music, as shown in Figure 15-1.

|

Table 15-1 Common Tempo Notation |

|

|

Notation |

Description |

|

Grave |

The slowest pace; very formal and very, very slow |

|

Largo |

Funeral march slow; very serious and somber |

|

Larghetto |

Slow, but not as slow as largo |

|

Lento |

Slow |

|

Adagio |

Leisurely; think graduation and wedding marches |

|

Andante |

Walking pace; close to the original minim |

|

Andantino |

Slightly faster than andante; think Patsy Cline’s “Walking After Midnight,” or any other lonely cowboy ballad you can think of |

|

Moderato |

Right smack in the middle; not fast or slow, just moderate |

|

Allegretto |

Moderately fast |

|

Allegro |

Quick, brisk, merry |

|

Vivace |

Lively, fast |

|

Presto |

Very fast |

|

Prestissimo |

Maniacally fast; think “Flight of the Bumblebee” |

Just to make things a little more precise, modifying adverbs such as molto (very), meno (less), poco (a little), and non troppo (not too much) are sometimes used in conjunction with the tempo notation terms listed in Table 15-1. For example, if a piece of music says that the tempo is poco allegro, it means that the piece is to be played “a little fast,” whereas poco largo would mean “a little slow.”

Speeding up and slowing down: Changing the tempo

Sometimes a different tempo is attached to a specific musical phrase within a song to set it apart from the rest. The following are a few tempo changes you’re likely to encounter in written music:

Accelerando (accel.): Gradually play faster and faster.

Accelerando (accel.): Gradually play faster and faster.

Stringendo: Quickly play faster.

Stringendo: Quickly play faster.

Doppio movimento: Play phrase twice as fast.

Doppio movimento: Play phrase twice as fast.

Ritardando (rit., ritard., rallentando, or rall.): Gradually play slower and slower.

Ritardando (rit., ritard., rallentando, or rall.): Gradually play slower and slower.

Calando: Play slower and softer.

Calando: Play slower and softer.

At the end of musical phrases in which the tempo has been changed, you may see a tempo, which indicates a return to the original tempo of the piece.

Dealing with Dynamics: Loud and Soft

Dynamic markings tell you how loudly or softly to play a piece of music. Composers use dynamics to communicate how they want a piece of music to “feel” to an audience, whether it’s quiet, loud, or aggressive, for example.

The most common dynamic markings, from softest to loudest, are shown in Table 15-2.

|

Table 15-2 Common Dynamic Notation |

||

|

Notation |

Abbreviation |

Description |

|

Pianissimo |

pp |

Play very softly |

|

Piano |

p |

Play softly |

|

Mezzo piano |

mp |

Play moderately softly |

|

Mezzo forte |

mf |

Play moderately loudly |

|

Forte |

f |

Play loudly |

|

Fortissimo |

ff |

Play very loudly |

Figure 15-2: The dynamic markings here mean you would play the first bar very softly, pianissimo, and the second very loudly, fortissimo.

Modifying phrases

Sometimes when reading a piece of music, you may find one of the markings in Table 15-3 attached to a musical phrase or a section of music generally four to eight measures long.

|

Table 15-3 Common Modifying Phrases |

||

|

Notation |

Abbreviation |

Description |

|

Crescendo |

cresc. < |

Play gradually louder |

|

Diminuendo |

dim. > ordecrescendo decr. > |

Play gradually softer |

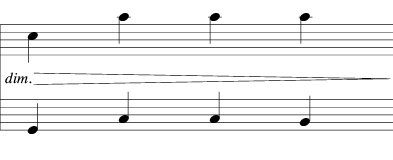

In Figure 15-3, the long <, called a hairpin, means to play the selection gradually louder and louder until you reach the end of the crescendo.

Figure 15-3: The crescendo here means play gradually louder and louder until the end of the hairpin.

In Figure 15-4, the > hairpin beneath the phrase means to play the selection gradually softer and softer until you reach the end of the diminuendo.

Figure 15-4: The diminuendo, or decrescendo, here means play gradually softer and softer until the end of the hairpin.

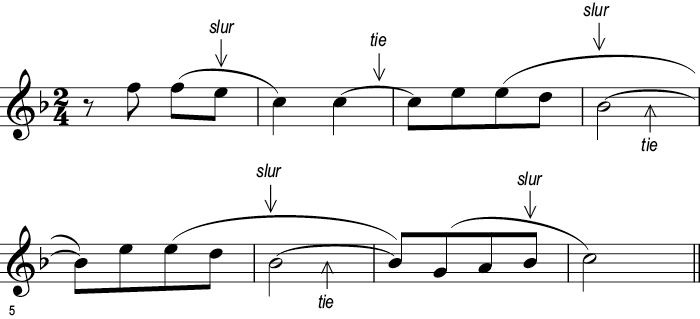

Another common marking you’ll probably come across in written music is a slur, which you can see in Figure 15-5. Just like when your speech is slurred and the words stick together, a musical slur is to be played with all the notes “slurring” into one another. Slurs look like curves that connect the notes.

Figure 15-5: Slurs over groups of notes.

Checking out other dynamic markings

You probably won’t see any of the following notations in a beginning-to-intermediate piece of music, but for more advanced pieces, you may find one or two (listed alphabetically):

Agitato: Excitedly, agitated

Agitato: Excitedly, agitated

Animato: With spirit

Animato: With spirit

Appassionato: Impassioned

Appassionato: Impassioned

Con forza: Forcefully, with strength

Con forza: Forcefully, with strength

Dolce: Sweetly

Dolce: Sweetly

Dolente: Sadly, with great sorrow

Dolente: Sadly, with great sorrow

Grandioso: Grandly

Grandioso: Grandly

Legato: Smoothly, with the notes flowing from one to the next

Legato: Smoothly, with the notes flowing from one to the next

Sotto voce: Barely audible

Sotto voce: Barely audible

Examining the piano pedal dynamics

Additional dynamic markings relate to the use of the three foot pedals located at the base of the piano (some pianos have only two pedals). The standard modern piano pedal setup is, from left to right:

Soft pedal (or una corda pedal): On most modern upright pianos, the soft pedal moves the resting hammers inside the piano closer to their corresponding strings. Because the hammers have less distance to travel to reach the string, the speed at which they hit the strings is reduced, and the volume of the resulting notes is therefore much quieter and has less sustain.

Soft pedal (or una corda pedal): On most modern upright pianos, the soft pedal moves the resting hammers inside the piano closer to their corresponding strings. Because the hammers have less distance to travel to reach the string, the speed at which they hit the strings is reduced, and the volume of the resulting notes is therefore much quieter and has less sustain.

Most modern grand pianos have three strings per note, so when you press a key, the hammer strikes all three simultaneously. The soft pedal is called una corda (“one string”) because it moves all the hammers to the right so that they only strike one of the strings. This effectively cuts the volume of the sound by two-thirds.

Middle pedal: If it’s present (many modern pianos have only the two outer pedals to work with), the middle pedal has a variety of roles, depending on the piano. On some American pianos, this pedal gives the notes a tinny, honky-tonk piano sound when depressed. Some other pianos have a bass sustain pedal as their middle pedal. It works like a sustain pedal but only for the bass half of the piano keyboard. Still other pianos — specifically many concert pianos — have a sostenuto pedal for their middle pedal, which works to sustain one or more notes indefinitely, while allowing successive notes to be played without sustain.

Middle pedal: If it’s present (many modern pianos have only the two outer pedals to work with), the middle pedal has a variety of roles, depending on the piano. On some American pianos, this pedal gives the notes a tinny, honky-tonk piano sound when depressed. Some other pianos have a bass sustain pedal as their middle pedal. It works like a sustain pedal but only for the bass half of the piano keyboard. Still other pianos — specifically many concert pianos — have a sostenuto pedal for their middle pedal, which works to sustain one or more notes indefinitely, while allowing successive notes to be played without sustain.

Damper pedal (or sustaining or loud pedal): The damper pedal does exactly the opposite of what the name would imply — when this pedal is pressed, the damper inside the piano lifts off the strings and allows the notes being played to die out naturally. This creates a ringing, echoey effect for single notes and chords (which can be heard, for example, at the very end of The Beatles’s “A Day in the Life”). The damper pedal can also make for a really muddled sound if too much of a musical phrase is played with the pedal held down.

Damper pedal (or sustaining or loud pedal): The damper pedal does exactly the opposite of what the name would imply — when this pedal is pressed, the damper inside the piano lifts off the strings and allows the notes being played to die out naturally. This creates a ringing, echoey effect for single notes and chords (which can be heard, for example, at the very end of The Beatles’s “A Day in the Life”). The damper pedal can also make for a really muddled sound if too much of a musical phrase is played with the pedal held down.

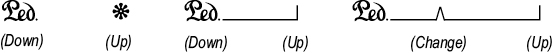

For example, in Figure 15-6, the “Ped.” signifies that the damper pedal (usually the foot pedal farthest to your right) is to be depressed during the selection. The breaks in the brackets (shown with ^) mean that in these places, you briefly lift your foot off the pedal.

Figure 15-6: Pedal dynamics show you which pedal to use and how long to hold it down.

Looking at the articulation markings for other instruments

Although most articulation markings are considered universal instructions — that is, applicable to all instruments — some are aimed specifically at certain musical instruments. Table 15-4 lists some of these markings and their respective instruments.

|

Table 15-4 Articulation Markings for Specific Instruments |

|

|

Notation |

What It Means |

|

Stringed instruments |

|

|

Martellato |

A short, hammered stroke played with very short bow strokes |

|

Pizzicato |

To pluck the string or strings with your fingers |

|

Spiccato |

With a light, bouncing motion of the bow |

|

Tremolo |

Quickly playing the same sequence of notes on a stringed instrument |

|

Vibrato |

Slight change of pitch on the same note, producing a vibrating, trembling sound |

|

Horns |

|

|

Chiuso |

With the horn bell stopped up (to produce a flatter, muted effect) |

|

Vocals |

|

|

A capella |

Without any musical accompaniment |

|

Choro |

The chorus of the song |

|

Parlando or parlante |

Singing in a speaking, oratory style |

|

Tessitura |

The average range used in a piece of vocal music |

The importance of tempo can truly be appreciated when you consider that the original purpose of much music was to accompany people dancing. Often the movement of the dancers’ feet and body positions worked to set the tempo of the music, and the musicians followed the dancers.

The importance of tempo can truly be appreciated when you consider that the original purpose of much music was to accompany people dancing. Often the movement of the dancers’ feet and body positions worked to set the tempo of the music, and the musicians followed the dancers. Practicing with a metronome is the best possible way to learn how to keep a steady pace throughout a song, and it’s one of the easiest ways to match the tempo of the piece you’re playing to the tempo conceived by the person who wrote the piece.

Practicing with a metronome is the best possible way to learn how to keep a steady pace throughout a song, and it’s one of the easiest ways to match the tempo of the piece you’re playing to the tempo conceived by the person who wrote the piece.

Play Track 93 to hear examples of 80 (slow), 100 (moderate), and 120 (fast) beats per minute.

Play Track 93 to hear examples of 80 (slow), 100 (moderate), and 120 (fast) beats per minute.