The law of inertia tells us what happens to an object when there are no unbalanced forces acting on it. Newton’s second law tells us what happens to an object that does have an unbalanced force acting on it: It accelerates in the direction of the unbalanced force. Another name for an unbalanced force is a net force, meaning a force that is not canceled by any other force acting on the object. Sometimes, the net force acting on an object is called an external force.

Newton’s second law can be stated like this: A net force acting on a mass causes that mass to accelerate in the direction of the net force. The acceleration is proportional to the force (if you double the force, you double the amount of acceleration), and inversely proportional to the mass of the object being accelerated (twice as big a mass will only be accelerated half as much by the same force). In equation form, we write Newton’s second law as

where Fnet and a are vectors pointing in the same direction. We see from this equation that the newton is defined as a kg∙m/s2, which is the equivalent of a little less than a quarter of a pound.

Newton’s second law can be written as: force equals mass times acceleration.

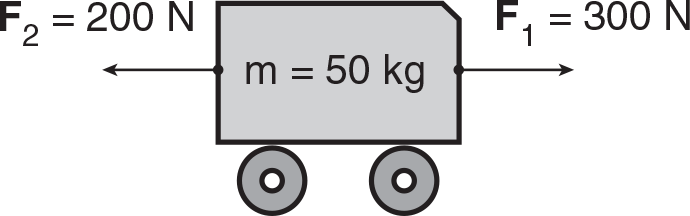

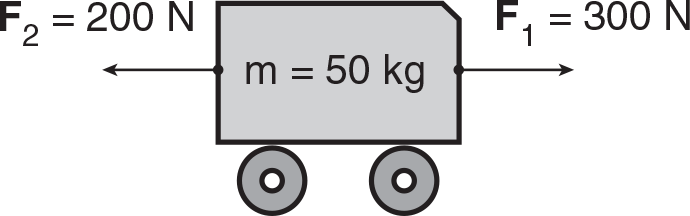

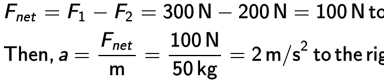

Example: Two ropes pull on a 50 kg cart as shown below. What is the acceleration of the cart?

Solution: Before calculating the acceleration of the cart using Newton’s second law, we must first find the net force. Since the rope on the right is pulling with a force that is greater than the force pulling to the left, the net force must be to the right and equal to the difference between the forces, since they are acting in opposite directions.

But what if the forces are acting at an angle other than 0° or 180°?

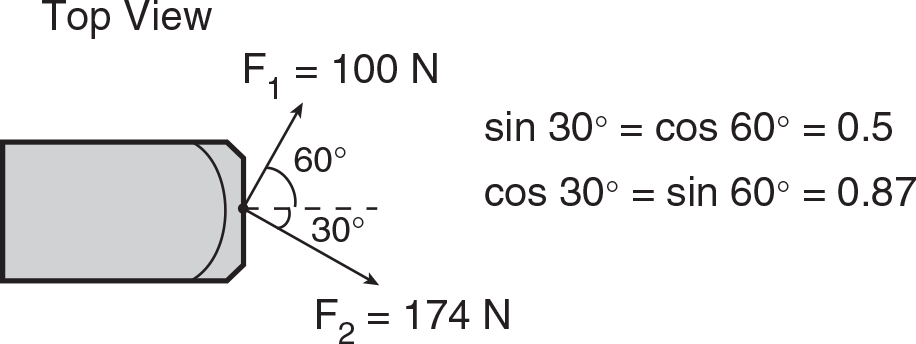

Example: Two forces act on a 40 kg sled resting on ice as shown from the top view below. What is the magnitude and direction of the acceleration of the sled?

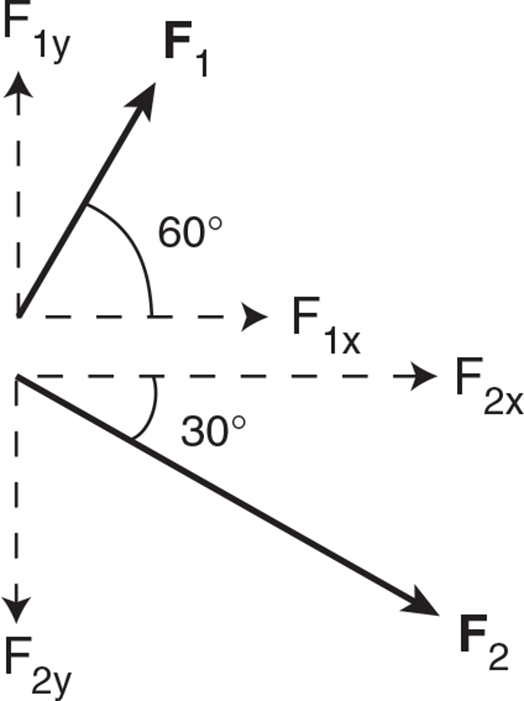

Solution: Once again we need to find the net force before we can find the acceleration of the sled. Since the weight of the sled or the normal force exerted by the ground on the sled do not affect the acceleration of the sled in this case, we will not include them in our diagram. Let’s break the forces down into their components:

Notice that the y-components of the forces cancel out, so we are left with a net force to the right:

So, the acceleration of the sled is

As mentioned earlier, mass is a measure of the inertia of an object. If you take a 1 kg mass to the moon, it will still have a mass of 1 kg. Mass does not depend on gravity, but weight does. The weight of an object is defined as the amount of gravitational force acting on its mass. Since weight is a force, we can calculate it using Newton’s second law:

Mass is the measure of the amount of substance in an object, and is measured in kilograms. Weight is the gravitational force pulling down on an object, and is measured in newtons.

In the preceding equation, the specific acceleration associated with weight is, not surprisingly, the acceleration due to gravity. Like any force, the SI unit for weight is the newton.

Example: Find the weight in newtons of a girl having a mass of 40 kg.

Solution: W = mg = (40 kg)(10 m/s2) = 400 N.

Since one newton is a little less than a quarter of a pound, this girl weighs about 100 lbs in U.S. Customary units.

A system is said to be static if it has no velocity and no acceleration. In other words, it’s at rest and it’s going to stay that way. According to Newton’s first law, if an object is in static equilibrium, the net force on the object must be zero. That doesn’t mean there are no forces acting on it; it means there are no unbalanced forces acting on it.

Always draw all of the forces acting on an object before answering a question about the forces or net force.

Example: Three ropes are attached as shown below. The tension forces in the ropes are T1, T2, and T3, and the mass of the hanging ball is 50 kg. What is the magnitude of the tension in each of the three ropes? (sin 30º = cos 60º = 0.5; sin 60º = cos 30º = 0.87)

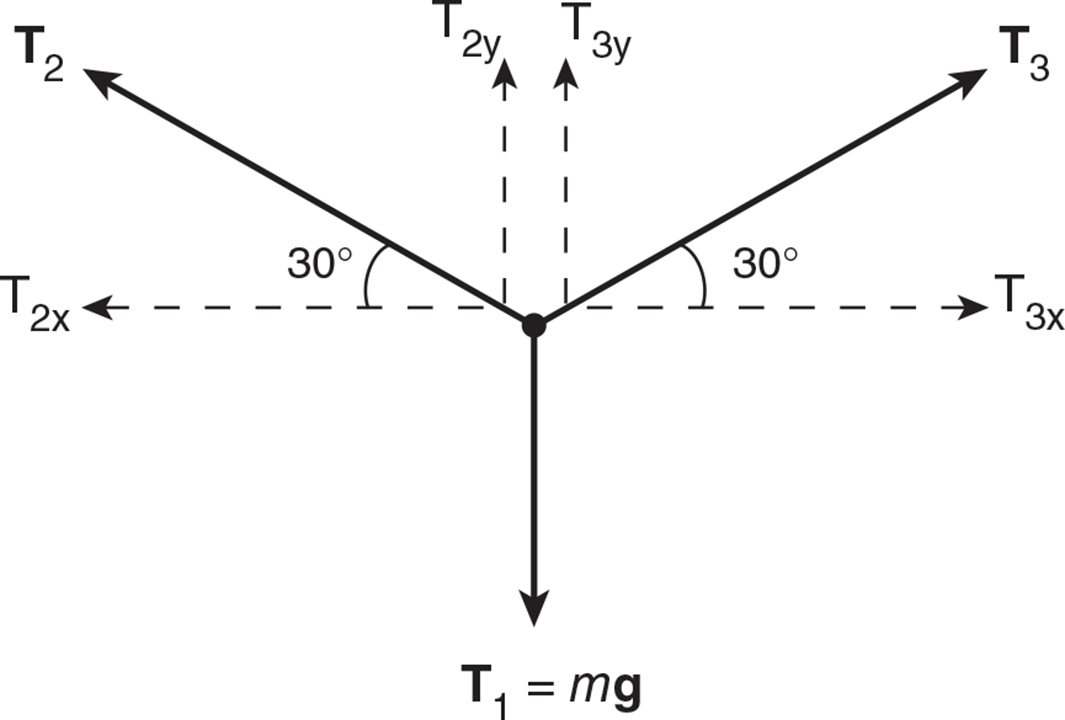

Solution: Since the system is in equilibrium, the net force on the system must be zero. We start by drawing a free-body force diagram of all the forces acting on point O. A free-body force diagram is a vector diagram of all of the forces acting on a mass.

Tension T1 is simply equal to the weight of the hanging ball:

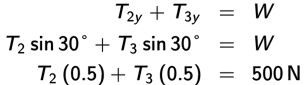

To find T2 and T3, we can break them down into their vector components:

Since the forces are in equilibrium, the vector sum of the forces in the x-direction must equal zero. Therefore:

The sum of the forces in the y-direction must also be zero:

Since T2 = T3, it follows that each tension is also equal to 500 N.

A typical example used to illustrate weight and Newton’s second law is a blocks and pulley system. Let’s look at a couple of examples of the blocks and pulley system.

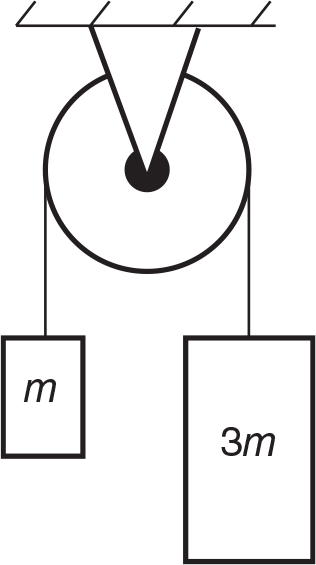

Example: Two blocks of mass m and 3m are connected by a string that passes over a pulley of negligible mass and friction, as shown below. The system is released from rest. In terms of the acceleration due to gravity g, what is the acceleration of the system?

Solution: First, we should draw a free-body force diagram for each block. There are two forces acting on each of the masses: weight downward and the tension in the string upward. Our free-body force diagrams should look like this:

Writing Newton’s second law for each of the blocks:

Notice that the tension T acting on block m is greater than block m’s weight, but block 3 m has a greater weight than the tension T. This is, of course, the reason block 3 m accelerates downward and block m accelerates upward. The magnitude of the tension acting on each block is the same, and the magnitudes of their accelerations are the same. Setting their tensions equal to each other, we get:

Canceling the masses and solving for a, we get:

Of course, the block of mass m accelerates upward, while the block 3 m accelerates downward.

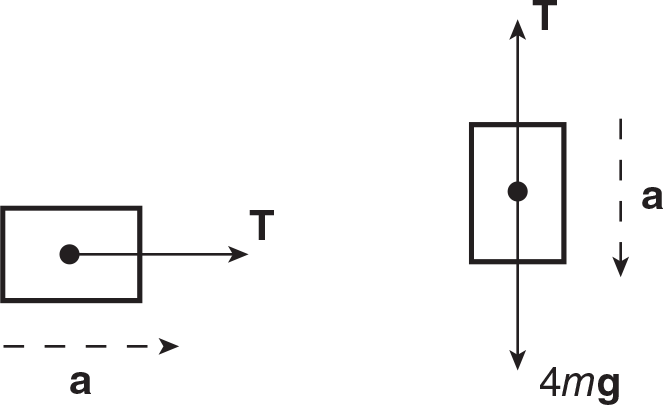

Example: A block of mass m rests on a horizontal table of negligible friction. A string is tied to the block, passed over a pulley, and another block of mass 4 m is hung on the other end of the string, as shown in the figure below. Find the acceleration of the system.

Solution: Once again, let’s draw a free-body force diagram for each of the blocks, and then apply Newton’s second law.

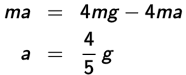

Setting the two equations for T equal to each other:

Could you have guessed at this solution before we worked it out? If the hanging mass 4 m were not connected to the mass m on the table, it would fall freely at g. Since it is connected to the mass, the weight of mass 4m must accelerate 4 m + m = 5 m of mass, resulting in an acceleration only  that of free-fall acceleration.

that of free-fall acceleration.

See if you can make an educated guess at the answer to a question before working it out, and eliminate impossible or unreasonable answers.