Early on Sunday morning, 7 December 1941, the inhabitants of the Hawaiian island of Oahu awoke to the sound of aircraft engines, guns and bombs exploding. Many thought it was another live firing exercise, but at 8.40 a.m. the local radio interrupted its programme. ‘Please pay attention,’ said the announcer. ‘The island is under attack. I repeat, the island is under attack by hostile forces.’

In fact, the Japanese had first attacked fifty-two minutes earlier, when 353 aircraft swooped in low over the sea. Torpedo bombers had caught the United States Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor completely by surprise, and within minutes all eight battleships moored there had been hit. Meanwhile, dive-bombers screamed down over the island’s air bases. A further 171 aircraft in the second wave roared in to attack a short while later, so that by the time the radio announcer told Hawaiians what was happening, the cream of the Pacific Fleet lay crippled: California had been half-sunk, West Virginia was ablaze and four other battleships were immobile and out of action. Worse, Oklahoma had capsized, while Arizona’s forward magazine had exploded, killing more than a thousand of her crew. Where once there had been ‘Battleship Row’ there was now a mass of twisted metal, angry flames and billowing thick smoke. And a lot of dead American servicemen. On the airfields, 188 aircraft had been destroyed and a further 159 damaged. Also hit were three cruisers, three destroyers and three other vessels.

Witnesses were stunned by how low the Japanese pilots flew. ‘Hell, I could even see the gold in their teeth,’ observed one American army officer. ‘It was like being engulfed in a great flood, a tornado or earthquake,’ said another. ‘The thing hit so quickly and so powerfully it left you stunned and amazed.’

The devastating attack proved how badly the Americans had underestimated the Japanese. There had been, however, plenty of indications that Japan was heading towards war, although little that suggested the US Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor was the target.

Japan’s growing aggression towards the West had been a long time in coming and at its core was the urgent need for resources. The origins for this change in Japanese ambition lay in the Meiji Revolution of 1868, in which the rule of the emperor was restored and the old feudal shogunate thrown aside. It was clear, though, that the country lagged industrially and commercially behind Britain, the United States, France and other global powers. In the decades that followed, Japan modernized very quickly, with a massive growth in industry and infrastructure. Shipyards were built, so too was a national railway, and the largely rural population began to migrate rapidly to the cities.

The trouble was, Japan was fairly resource-poor and her burgeoning urban population and growing middle class needed the food and comforts of a modern, industrialized nation. Britain, similar in size to Japan, had a large global trading empire and overseas possessions. Now Japan began developing ambitions to have an empire of her own.

An obvious source of resources was China. Japan invaded Manchuria in north-east China in 1931, but while there were numerous engagements and sporadic fighting in the years that followed it was not until 1937 that Japan and China became embroiled in full-scale war.

Sweeping Japanese victories ensued, along with merciless brutality towards many hundreds of thousands of Chinese civilians. Yet the invaders were unable to complete their victory. The Chinese, under the military rule of General Chiang Kai-shek, offered more resistance than Japan had anticipated.

In fact, the continuing war meant Japan’s situation was not improving but worsening, despite her gains. In the summer of 1939 there was a drought and a critical shortage of water, as well as of coal, which led to restrictions in electricity. The drought also led to a drastically reduced production of rice and to food shortages. By early 1940 the Japanese trade treaty with the USA had lapsed with no hope of renewal. Fear that imports, especially those from the US, would be cut off led to the urgent purchasing of overseas war materiel, which in turn meant foreign-exchange reserves were being allowed to run low.

By the autumn of 1941, Japan held most of the eastern coastal area of China and Indochina (Vietnam), but at great cost and with ongoing resistance and guerrilla fighting with which to contend. Militarily, Japan was reasonably well equipped with soldiers, aircraft and a large, powerful and modern navy, but was dependent on the United States, especially, for steel, oil and other essential raw materials. Once the American source was cut off, her ability to build on her gains would be limited unless she could successfully tap the resources of the Far East, the best of which lay in the hands of the British, the Americans and the Dutch.

The problem was, doing so would mean war with those powers. Throughout the 1930s, Britain and the United States had watched Japanese aggression with increasing concern. The Tripartite Pact between Japan, Germany and Italy in September 1940 set more alarm bells ringing. Fears grew further when Japan signed a non-aggression pact with her old enemy the USSR, then moved into Indochina, worryingly close to British-held Malaya and Singapore and the US Philippines.

Even so, the Allies felt Japan was unlikely to risk war any time soon, despite the latter sending increasing numbers of troops into Indochina. In an effort to deter the Japanese further, the US President, Franklin D. Roosevelt, imposed an embargo on all oil and fuel to Japan and stepped up supplies to China. Bombers were sent to the Philippines and the Pacific Fleet was posted to Pearl Harbor.

The Japanese Prime Minister, Fumimaro Konoe, offered to withdraw troops from much of China and Indochina and suggested talks, but his proposals were rejected by Roosevelt. Tragically, the Americans underestimated Japan’s dilemma and in so doing overestimated the strength of their own hand.

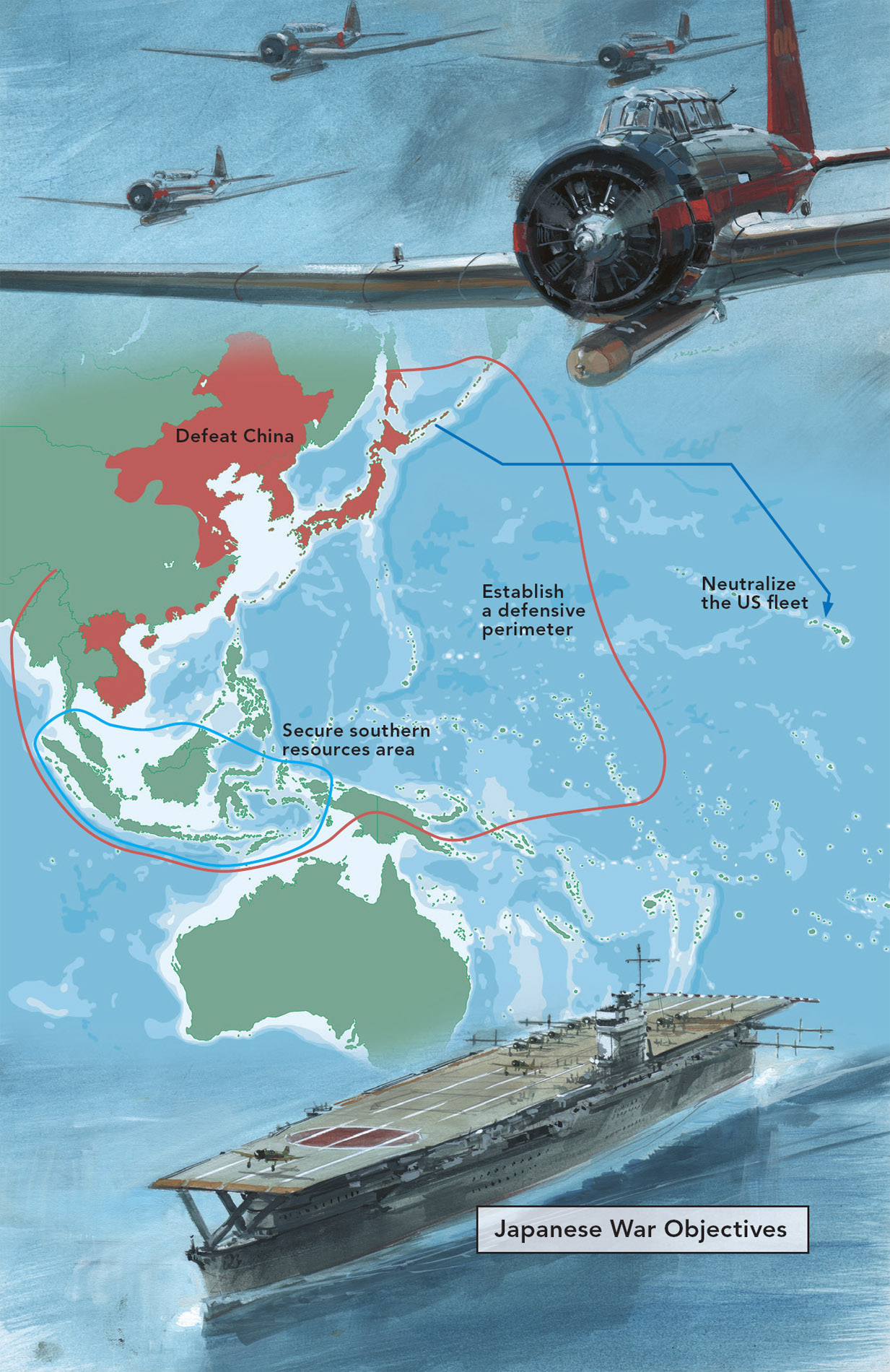

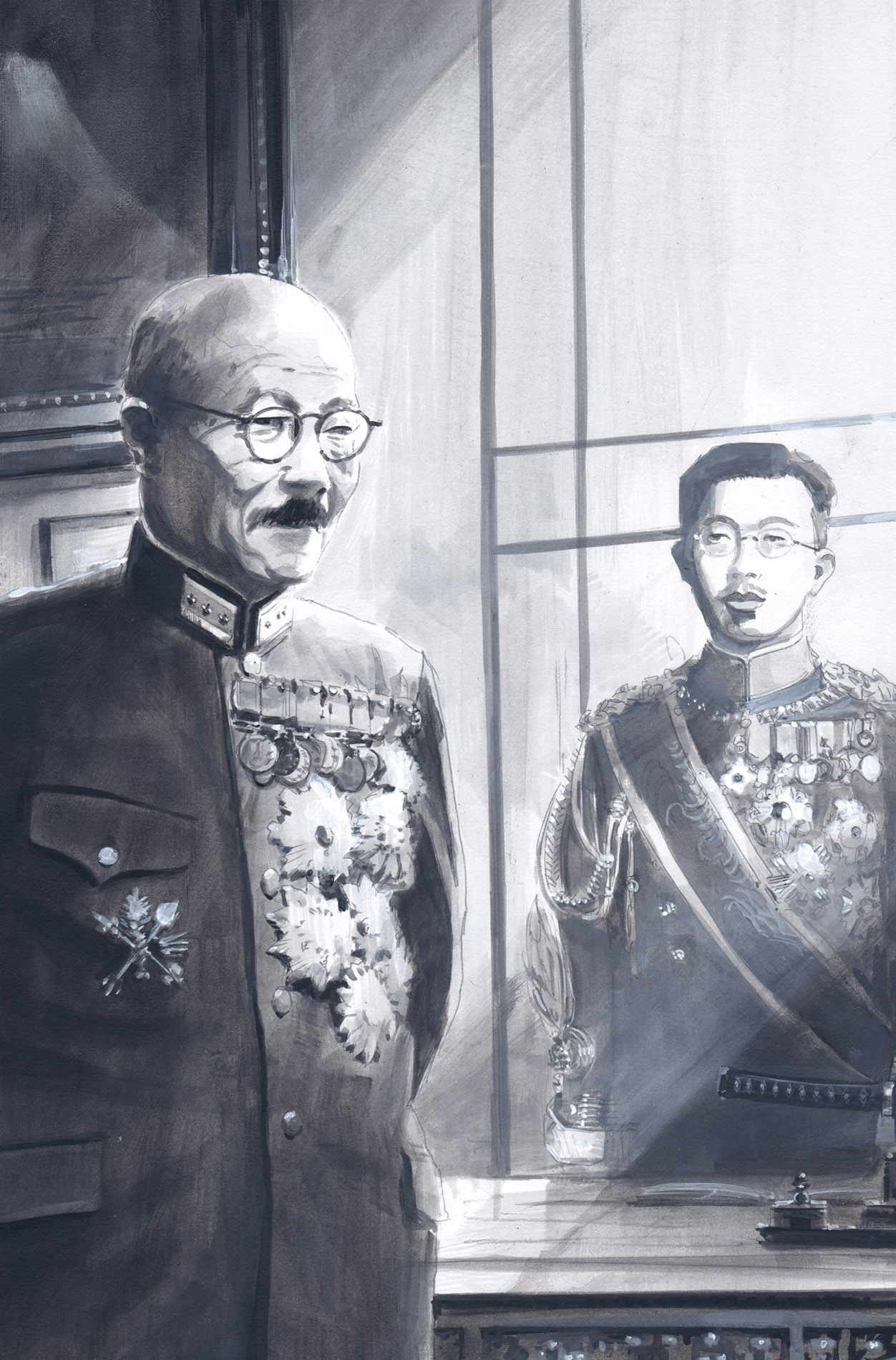

Konoe resigned and was replaced by General Hideki Tojo, one of Japan’s leading war hawks, and by early November 1941 both Emperor Hirohito and the new government had accepted that war was now unavoidable. The plan was to strike rapidly and decisively, and in such a way as to give Japan breathing space to then grab vital British, Dutch and American possessions in the Far East. By the time America had recovered from the blow, they would hopefully come to some kind of settlement, but with Japan now holding a vastly widened and resource-rich Pacific empire.

After the First World War, the United States had largely withdrawn from the world stage. Her armed forces were dramatically reduced in size and Big Business vilified as ‘merchants of death’ for having profited from the war. Legislation introduced in the early 1930s imposed new restrictions and stifled the ability of American companies to make arms. There was also a prevalent belief that if a country had a large military, it would inevitably use it, and that the converse was also true. In short, the Americans had become firm isolationists.

By the outbreak of war in September 1939, the United States was languishing with the nineteenth largest army in the world, behind Portugal, and with just seventy-four fighter planes in the Army Air Corps, a cavalry still dependent on horses, very few tanks, no anti-tank guns at all and not one manufacturer of explosives in the country.

President Roosevelt was, however, becoming increasingly concerned that the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans were no longer the great defensive barriers they had once been. Technology was advancing fast. The trouble was, precious few agreed with him and another presidential election was due in November 1940. No one had ever before stood for three terms, but Roosevelt rightly believed he was the best person to steer the USA through the choppy waters ahead.

With the collapse of France in May 1940, he began the process of rearming, launching a major campaign to persuade Americans of its necessity. Restrictive legislation was repealed and key advisors from big business – the ‘dollar-a-year’ men – were brought in. In November 1940, he was re-elected for an historic third term, and with his authority and ability to shape US rearmament substantially increased.

This meant that, while the United States had been in no way ready for war in September 1939, by December 1941 it was beginning to show its enormous industrial muscle. Tanks, aircraft and guns were starting to roll off the production lines in ever increasing numbers.

The US Navy was growing too. Of all the services, the navy had suffered the least in the inter-war years, and by December 1941 had 17 battleships, 7 aircraft carriers and 18 heavy cruisers, compared with the Japanese Imperial Navy’s 10 battleships, 6 aircraft carriers and 18 heavy cruisers. Perhaps more significant was the number of new US Navy warships under construction, including a further 15 battleships and 11 carriers. In contrast, the Japanese were building 3 new giant battleships and just 7 new carriers. Although the US Navy was only slightly largely than the Japanese Navy in December 1941, that gulf was set to widen.

Even so, the attack on Pearl Harbor stunned the Americans; Roosevelt said 7 December would ‘live in infamy’. A few days later, Hitler declared war on the USA too, believing America would now focus all its efforts in taking on Japan. He was, however, very much mistaken, because the Americans and British had already agreed that Germany posed the greater immediate threat, not least because of its advances in science and technology, and this was reaffirmed at their first wartime conference in Washington that December.

A ‘Germany first’ strategy, however, did not mean the Americans – or British for that matter – would sit back in the Far East and Pacific. Far from it. Admiral Ernest King, the new commander-in-chief of the US Fleet, intended to strike back hard. And soon.

The attack on Pearl Harbor was, however, just the start of a series of superbly planned and dramatically fast strikes on British, Dutch and US possessions in the Far East. On 8 December, the US island of Guam fell within half an hour and Wake Island, 1,500 miles to its east, was also taken despite brave resistance from the small force of US Marines and construction workers there. Both islands were key stopping points and airfields in the Pacific. Borneo was invaded, while the British territory of Hong Kong was overwhelmed by 40,000 Japanese troops. Two of the Royal Navy’s three battleships, Prince of Wales and Repulse, were sunk on the same day, 12 December. The Philippines were also attacked and vital airfields clinically knocked out. Manila, the capital, fell on 3 January.

Further defeats and humiliations followed. Malaya was invaded and, although the British forces were double the strength of General Tomoyuki Yamashita’s in numbers, they lacked guns and any tanks, and had only 158 outdated aircraft compared with Japan’s 617 modern planes. Yamashita’s men were well trained and battle-hardened from the war in China; the British troops were neither. General Arthur Percival, the British commander, had allowed his forces to become too dispersed across the peninsula, which enabled the Japanese to defeat them in penny packets. Yamashita’s naval strength was also vastly superior, which meant he could leapfrog his forces down the coast and so outmanoeuvre the British.

Kuala Lumpur, the capital of Malaya, fell on 12 January and the rest of the country by early February. This was followed swiftly by the fall of Singapore, where, on 15 February, Percival surrendered 130,000 British, Australian and Indian troops. In terms of numbers, it was the worst defeat ever in British history.

Losses came at sea as well as on land. On 27 February a joint British, Dutch, American and Australian naval force was smashed at the Battle of the Java Sea, and the commander, the Dutch Rear-Admiral Karel Doorman, killed. These were catastrophic defeats. Quite simply, the British had been caught napping. With attention almost entirely on the war in the West, and underestimating the imminence and strength of the Japanese threat, Britain had left her Far East colonies dangerously under-prepared. Malaya was Britain’s richest territory, with crucial supplies of rubber, timber and quinine. Now Burma, which supplied British India and her interests in the Far East with oil, was also under threat.

Fierce battles continued in the Philippines and Borneo, while Australian New Guinea was also overrun, as were the Solomon Islands and Bougainville to the north of Australia. This threatened the crucial shipping channel between the US and Australia. The Dutch East Indies were also lost.

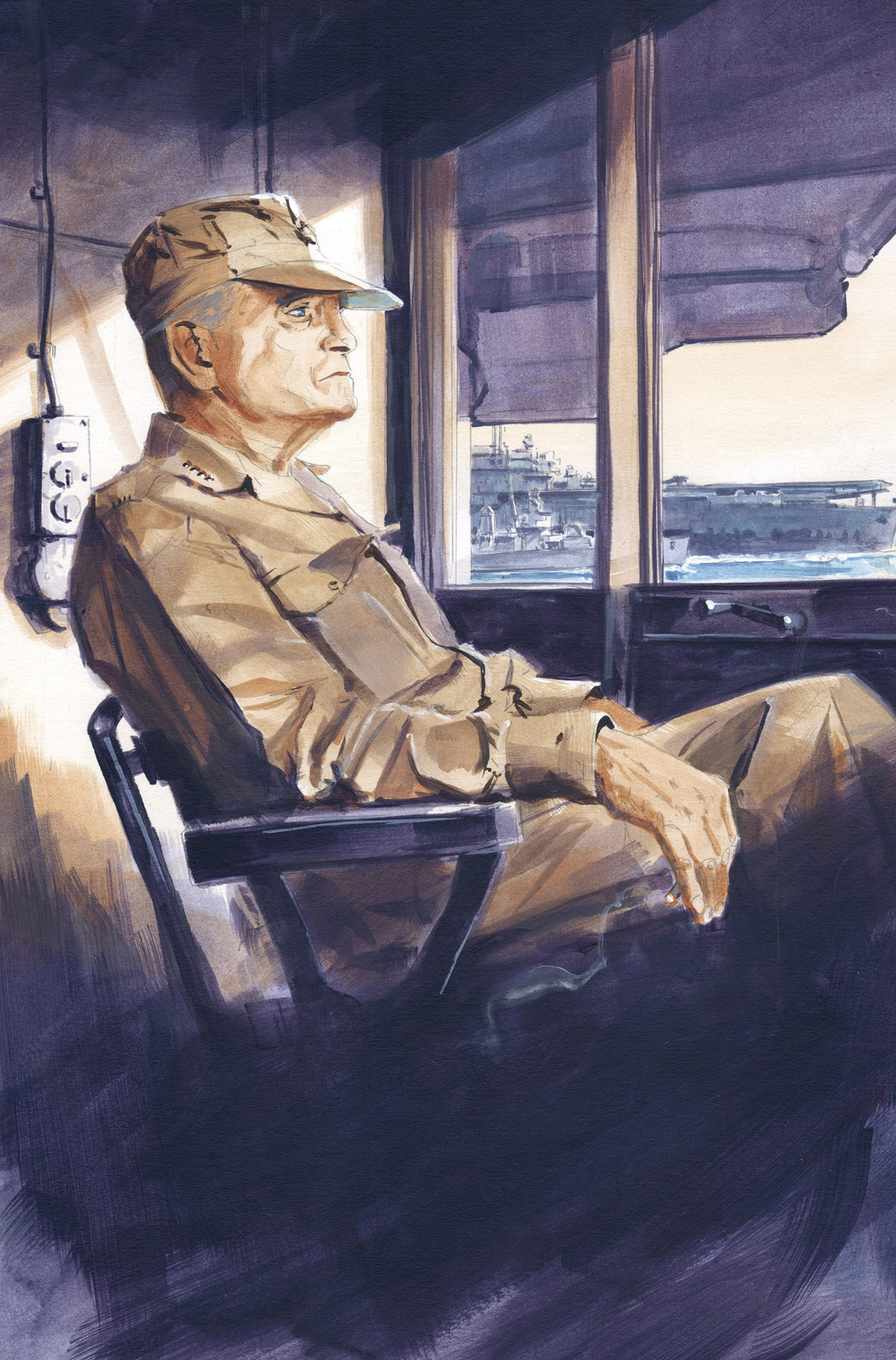

In the Philippines, the Americans retreated into the Bataan Peninsula, but throughout March were increasingly running short of supplies. Roosevelt ordered General Douglas MacArthur to fly to Australia rather than risk capture. ‘I came out of Bataan,’ he said on arriving there on 20 March, ‘and I shall return.’ The remaining US troops in the peninsula, malnourished and short of arms, finally surrendered on 10 April. Neighbouring Corregidor fell on 8 May. The loss of the Philippines was complete.

The many Allied troops who had suddenly become prisoners were now subjected to hell on earth. Their treatment in Japanese prisoner-of-war camps was appalling. Facing often random and extreme violence and deprivation, many simply did not survive their incarceration.

This excessive cruelty was a shock to the soldiers fighting the Japanese. Allied forces had a very different attitude to being taken prisoner than the Japanese, who had developed a code of discipline, sacrifice and military honour, borrowed in part from the old shogunate culture but given a new twist by the ultra-nationalist and militaristic elite that had emerged around the cult of the Emperor Hirohito. No one person exemplified this growing culture more than the new Prime Minister, Hideki Tojo.

‘If two hundred Japs held a block, you had to kill all two hundred,’ General Philip Christison would write some time later of his experiences of taking on the Japanese in Burma. ‘None would surrender. None would retire.’ Japanese soldiers regularly beheaded, crucified, eviscerated and beat those they captured. The Allies began to regard their enemy as inhuman, almost superhuman, such was their unshakeable discipline and preference for death over the dishonour of being captured.

Japan’s soldiers, sailors and airmen were themselves subject to sadistic treatment and degradation in training. There can be little doubt that this brutalization and dehumanization affected how they treated Allied prisoners. But it meant that, on the ground, Japanese commanders could rely on soldiers to travel lightly with minimum comfort and maximum discipline and replenish supplies from those captured. Speed of manoeuvre was key.

Japanese naval fighter pilots were a case in point. The regular beatings they endured in training were seen as a form of education to harden them. Nothing, however, was greater than the fear of failure and the humiliation that came with it. Recruits spent a year training on the ground, including learning to improve their eyesight and the ancient principles of kendo, Japanese swordsmanship. Flying training was also intense and protracted. British and German pilots were sent to front-line squadrons after around 150 hours. For Japanese pilots, it was some 500.

They were flying superb aircraft too. The ‘Zero’, for example, based around an original aero-engine bought from the US, then copied and improved, was a machine that actually exceeded every one of its design specifications. It was light, fast, long-range, well armed and had fingertip agility. In early 1942 there was nothing in the Allied arsenal to touch it. Superb machines combined with exceptionally trained and highly disciplined pilots were proving a stunning combination and demonstrated how important Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, commander of the Imperial Fleet, thought carrier-borne naval operations in the Pacific would be in the war that was rapidly unfolding.

For the first four decades of the twentieth century, it had been the battleship that had dominated the seas in times of war. That had now changed dramatically, which was why the prime target of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor had been the US Main Fleet’s aircraft carriers. Yet stunning though that attack had been, not one American carrier had been at Pearl Harbor at the time. The US had been thrown a lifeline that Admiral King and the equally new Pacific Fleet commander, Admiral Chester Nimitz, were determined not to squander.

While the Royal Navy was playing a dominant role in the Atlantic and Mediterranean, it was agreed that the US Navy would take the lead in the Pacific. Admiral King’s strategy was clear and based around two fundamental factors: first, Hawaii could not be allowed to fall; and second, nor could Australia. He ordered Nimitz to make it his first priority to secure the seaways between Hawaii and the island of Midway, just to the east of the International Date Line, and the North American mainland. His second priority was to make safe the routes to Australia. Fiji and the Samoan and Tonga islands needed to be made secure as crucial strongpoints along the way, and from these bases a counter-offensive could be launched up through the Solomons, New Guinea, Borneo and then, in time, the Philippines. It was unquestionably the right strategy.

On 1 February, the US Navy’s fightback began with a series of raids on shipping and airfields on the Japanese-held Marshall Islands. Although the material damage was less than was at first thought, the Americans learned vital lessons and their counter-offensive was under way.

Further US carrier raids were mounted, but the first major naval clash came in May. The Japanese now plotted to disrupt Allied plans by invading and occupying Port Moresby in New Guinea and also the island of Tulagi in the Solomons. American cryptanalysts had broken Japanese codes, however, and, learning of their intentions, sent a joint US–Australian naval force of carriers and cruisers to intercept and stop the enemy.

Tulagi was invaded on 3–4 May, but the Japanese had been surprised to come under attack by American aircraft from the carrier Yorktown. They now advanced to meet the Allied naval forces, clashing in the Coral Sea on 7 May.

This was the first battle in which aircraft carriers engaged one another, and the Americans and Japanese lost one each and suffered damage to the others. On 8 May, US radar screens picked up enemy aircraft heading towards USS Lexington and Task Force 17, and her Wildcat fighters were scrambled to meet them. Then, at 11.13 a.m., lookouts spotted the black dots of enemy aircraft. As they approached, the attacking torpedo bombers split into two groups while enemy dive-bombers peeled over and down towards the Lexington, which was now taking evasive action by swerving frantically. The Japanese planes met a wall of anti-aircraft fire as well as the Wildcats. ‘It seemed impossible we could survive our bombing and torpedo runs,’ said Lieutenant Commander Shigekazu Shimazaki, the Japanese attack commander. ‘Our Zeros and enemy Wildcats spun, dove, and climbed in the midst of our formations. Burning and shattered planes of both sides plunged from the skies.’

Despite the heroic defence, Lexington was hit by both bombs and torpedoes, but, amazingly, fire-damage parties managed to restore her to seagoing order before a series of explosions ensured the mighty carrier would have to be abandoned and scuttled.

With both sides suffering heavy losses of aircraft as well as ships, the battle ended as dusk fell on the second day. Crucially, the Battle of the Coral Sea ensured that the Japanese abandoned their plans to invade New Guinea.

Meanwhile, on land, Japanese forces were pushing the British out of Burma. Sent out to oversee the retreat and ensure vital oilfields were destroyed and denied to the Japanese was Lieutenant-General Harold Alexander. With his Burma Corps commander, Major-General Bill Slim, the British forces successfully escaped across the wide Irrawaddy River and back into India. Many Indian civilians living in Burma faced a more difficult flight and thousands perished. It was a tragedy for them and a further dent to British moral authority in India, where the Free India movement was growing stronger. India, the jewel in the British Empire’s crown, now appeared under threat both from within and from the Japanese.

Despite their incredible successes, cracks were emerging between the Japanese Army and Navy over future strategy. While these disputes were going on, sixteen American B-25 bomber crews, led by Lieutenant-Colonel Jimmy Doolittle, had flown off the USS Hornet on 18 April and bombed Tokyo. Damage had been slight but it had shown the Japanese they were not invulnerable and helped Yamamoto’s Pacific naval strategy. Instead of pushing into Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), which they had already attacked, and into India, as favoured by the army, Yamamoto instead won the internal battle with his defensive barrier strategy in the Pacific. His plan was to destroy the US Navy’s carrier fleet then extend Japanese possessions with the swift capture of Samoa, Fiji and even Hawaii.

Yamamoto’s aim was to lure the Americans into a trap around Midway, but hubris got the better of him. His plan was overly complex and based on faulty intelligence about US strength and morale. The consequence was a terrible error of judgement.

Yamamoto hoped to entice the US Pacific Fleet into battle by separating his forces, with his carriers and battleships several hundred miles apart. The plan was to attack the enemy carriers, then follow up with his battleships and cruisers, who would engage whatever American ships remained.

Once again, American code-breakers intercepted enemy signal traffic and learned of Yamamoto’s plan. Because the Japanese forces were so far apart, they were no longer able to support one another. Furthermore, Nimitz’s Pacific Fleet was stronger than Yamamoto had appreciated. In contrast, the Japanese still had two carriers out of action from the Battle of the Coral Sea.

The clash began on 4 June, with Admiral Nimitz commanding his fleet in person. Japanese reconnaissance flights were poorly mounted, and when their air forces approached they were picked up on radar, and US naval fighter planes scrambled to meet them. At the same time, American bombers were hurriedly sent to attack the Japanese carriers while the enemy aircraft were airborne and the ships were considerably more vulnerable. Japanese anti-aircraft defence was surprisingly poor and definitely an Achilles heel.

In the ensuing four-day sea and air battle, the Japanese lost four of the six carriers that had attacked Pearl Harbor six months earlier, one heavy cruiser and 248 carrier-based aircraft, while the Americans had just one carrier sunk – Yorktown – along with one destroyer and 150 aircraft. Losses of men were ten times higher for the Japanese.

Midway did not turn the tide against Japan, but it was a major victory for the United States and did decidedly shift the balance in the Pacific.

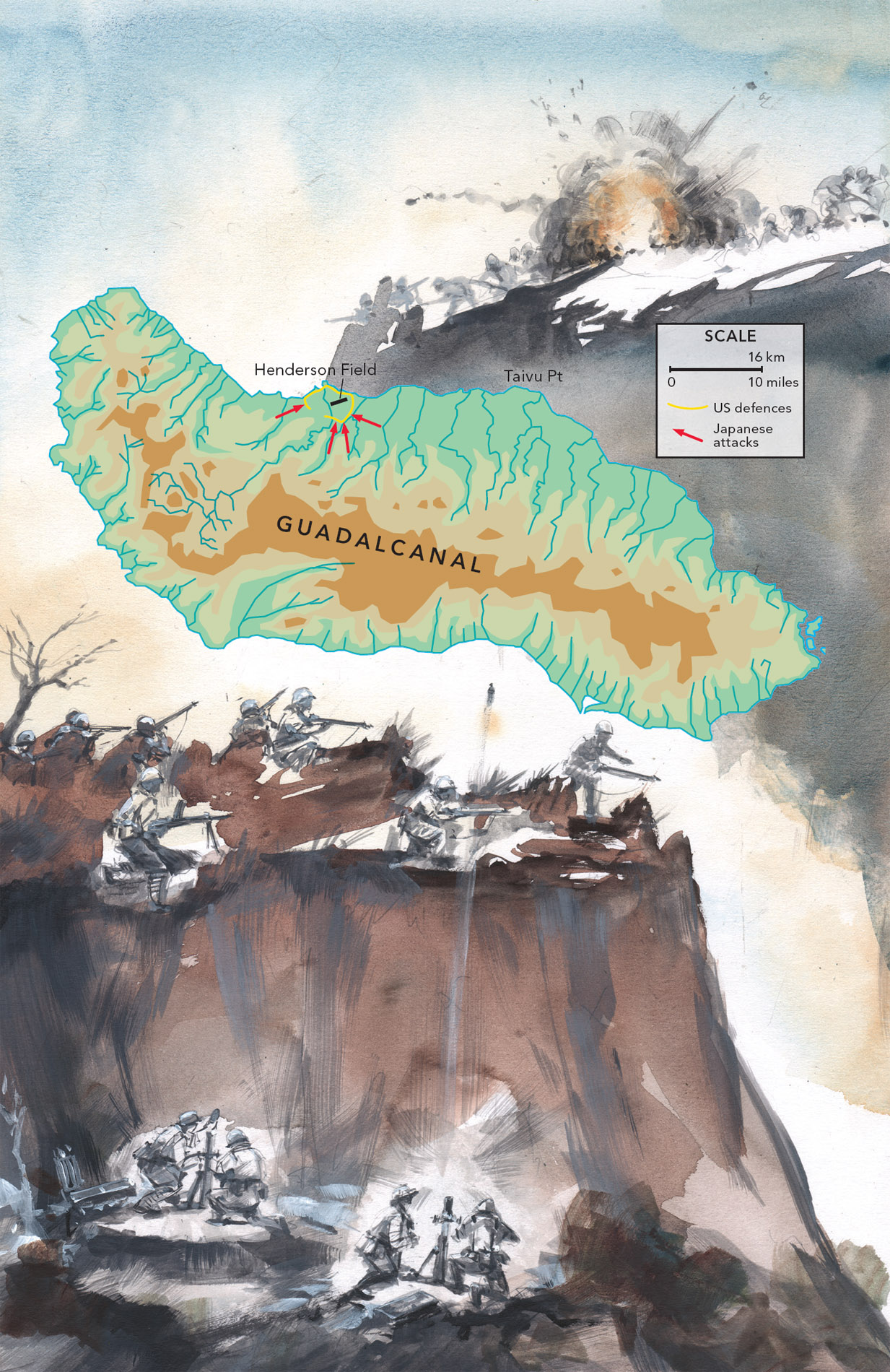

Guadalcanal in the Solomons, populated by 100,000 Melanesians, was a remote and underdeveloped British island of inhospitable jungle and hills, largely untouched by the modern world. From tiny Tulagi, which they had seized and occupied in May, the Japanese now landed troops on Guadalcanal and in early June started to build an airfield in the jungle.

A couple of weeks later, Admiral King ordered the US Navy to assault, capture and hold Guadalcanal – he was clear there could be no static defence. What’s more, he insisted Operation WATCHTOWER, as it was to be called, was to take place in just five weeks’ time, in early August. This was a massively ambitious undertaking. Overall command was given to Vice-Admiral Robert L. Ghormley, who had set up the headquarters of US South Pacific Forces in New Zealand just five weeks earlier. Troops were to come from the 1st Marine Division, who were mostly still at sea and had been promised six months’ training in New Zealand before going into action.

A support air-and-supply base, from which the operation could be launched, was needed very quickly. The island of Espiritu Santo, more than 500 miles away, was chosen and, although far from ideal, would have to do. Naval construction battalions, known as ‘Seabees’, worked around the clock, under floodlights at night, for a month and, incredibly, by 28 July an airstrip had been built on Espiritu Santo.

Major-General Alexander Vandegrift, commander of the 1st Marine Division, had been speechless when he learned his orders. ‘I could not believe it,’ he recalled. His men had had no amphibious training and little was known about Guadalcanal. However, orders were orders. In the precious time available, he was determined to make his men as ready as they could be.

Despite intense training, the Marines felt barely prepared. However, luck was with them. Poor weather hid the advance of the vast US armada and amphibious force, while as the landing craft sped towards the northern Guadalcanal coast on the morning of 7 August, the seas had become as smooth as ice. The Marines landed on Guadalcanal unopposed and also quickly overran the Japanese on Tulagi following a naval artillery barrage that caught the enemy completely off guard. By the following day, the airfield, newly completed by Japanese labour, had been captured by the 11,000-strong force of Marines.

Under-defended Guadalcanal may have been, but the Japanese were quick to respond, hurriedly sending a force of cruisers and destroyers from Rabaul, some 650 miles away in New Britain, and scrambling naval aircraft to attack. Later that day, a furious air battle raged over western Guadalcanal and nearby Savo Island, while by the night of 8/9 August Japanese naval forces had reached the area and attacked the Allied screening force commanded by the British Rear-Admiral Victor Crutchley, VC. In the ensuing battle, the Allies suffered a heavy defeat, much of it watched by the Marines now digging in around the airfield. Dangerously crippled, it was decided the naval forces should withdraw, even though only half the supplies had been unloaded.

Understandably, the Marines felt rather abandoned. A patrol sent to clear the outpost of enemy troops at Matanikou, some miles to the west of the newly named Henderson Field, was butchered, but a heavier follow-up attack wiped out the enemy. Two squadrons of Wildcats and a further squadron of Dauntless dive-bombers also landed at the airfield. It seemed it was only a matter of time, though, before the Japanese reinforced the island.

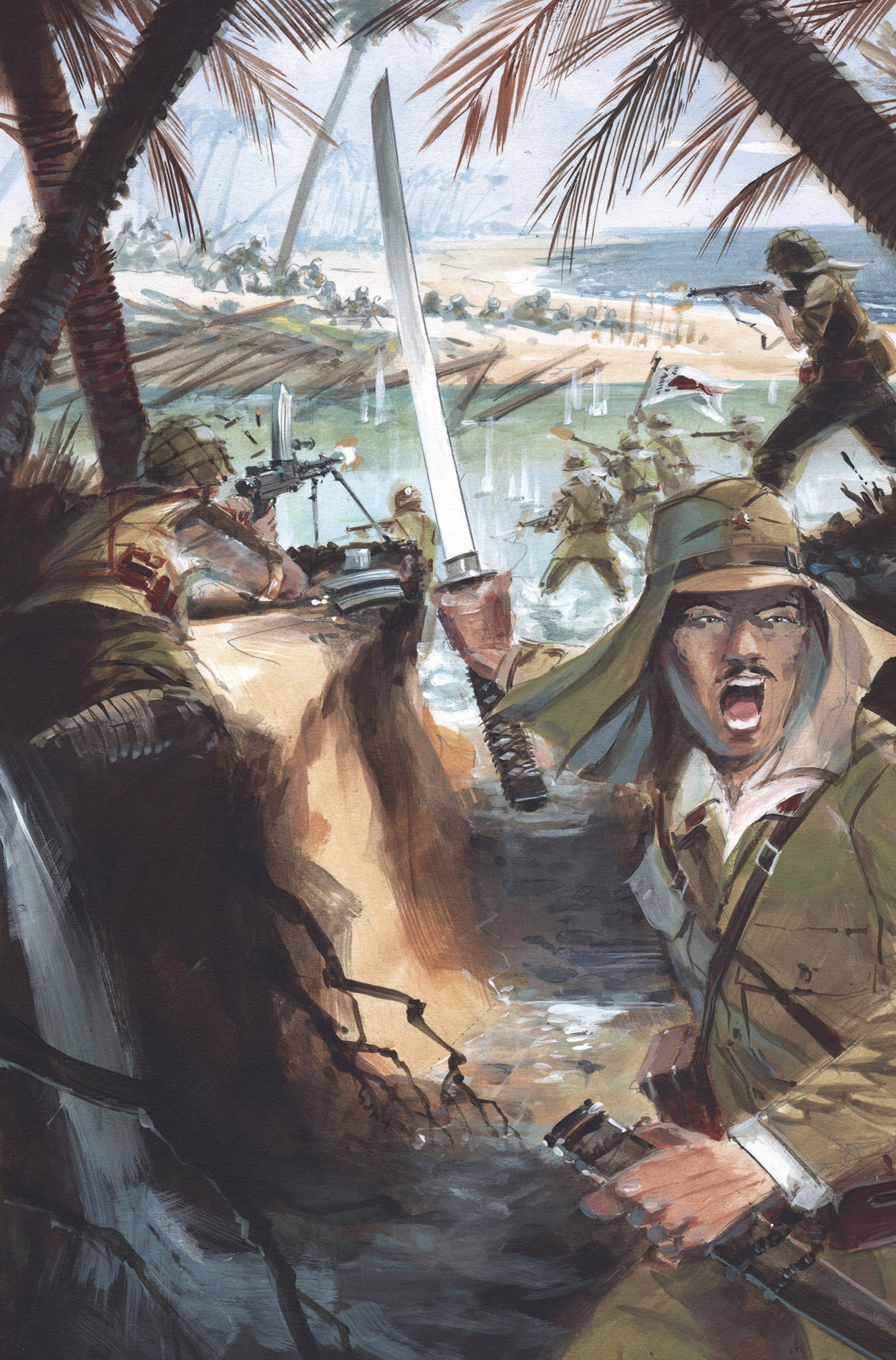

As predicted, the enemy had every intention of retaking Guadalcanal and began gathering both troops and large naval forces. The first 917 men of Japan’s 35th Infantry Brigade landed at midnight on 21 August well to the east of the Marines, then over 800 of them marched 9 miles to make a frontal attack on the Marines dug in on the western bank of the River Ilu, known to the Americans as Alligator Creek. It was a bloodbath. The Japanese were slaughtered, with just thirty survivors rejoining the 100-strong reserve who had remained behind where they had landed.

Meanwhile, more Japanese troops were on their way, as were considerable naval forces. The US naval task forces under Vice-Admiral Frank Fletcher also returned and on 24 August the two forces clashed, while the Japanese attacked from the air. A couple of months earlier, Guadalcanal had been a remote and largely unknown island in the South Pacific. By the end of the August 1942 it had become the scene of a bitter struggle on land, in the seas around it and in the air above.

The stage was now set for a truly decisive clash of arms.

While the Imperial Japanese Navy still had greater numerical strength, unless they delivered a knock-out and decisive blow against the Americans quickly, they would soon be ground down by the greater industrial strength of the United States. As it was, the remoteness of the Solomon Islands was already testing the logistical efforts of both sides to the utmost.

Both were now frantically trying to build up strength. More men, ships and aircraft were arriving from the US, while the Japanese were bringing up reinforcements via a system they dubbed the ‘Rat Express’: a fast destroyer would arrive at night from Rabaul, deposit men at Taivu Point in the Solomons, then scurry back. Between 29 August and 4 September, these ships landed almost 5,000 Japanese soldiers, now under command of General Kiyotake Kawaguchi.

His men attacked a long, 1,000-yard ridge that ran diagonally to the south of Henderson Field. This had already been picked out as a key feature and was defended by the Marines of Lieutenant-Colonel Merritt A. Edson’s 1st Raider Battalion, who were well dug in and expecting an attack. It came at around 7.30 p.m. on 13 September, with wave after wave of Japanese charging with rifles, bayonets and swords into the lethal fire of American machine guns and Tommy guns. Once again, they were gunned down in their hundreds and their attack stopped dead. More than 1,200 were killed or later died of wounds. Fanatical ‘banzai charges’ were certainly terrifying to come up against but, as the Marines were discovering, disciplined defence could quickly turn them into suicide charges. This vital high ground became known as ‘Bloody Ridge’, but it was mostly Japanese blood that was spilled that night. By comparison, total American casualties – missing, dead and wounded – were 143.

Following this defeat, the Japanese Imperial General Staff began to fear that Guadalcanal would become the decisive battle of the war. They were not wrong. Troops were withdrawn from the ongoing battle in New Guinea to reinforce Guadalcanal, while the Americans brought in more men and also two more carrier task forces.

But it was the Japanese who were winning the reinforcement battle. Over the first two weeks of October, a further 15,000 troops were landed by the Tokyo Express, while on the night of 13/14 October Henderson Field was pummelled by a barrage of 14-inch guns from the battleships Kongō and Haruna, which churned up much of the airfield, destroyed key supplies of fuel and killed forty-one men. The Marines referred to it simply as ‘the Night’.

By mid-October, General Vandegrift’s men were beginning to despair, exhausted by the fighting and the conditions. They were short of food, stricken by malaria, dysentery and foot rot; the island was a brutal place in which to exist in the open, let alone fight. ‘We all feared defeat and capture,’ said one soldier. ‘We were afraid they were going to leave us there.’

There was also a growing feeling among the Marines that the US Navy was not doing enough to support them – either aggressively at sea or in supplying them. The Japanese were willing to take risks, so why wasn’t Admiral Ghormley?

On 15 October, Nimitz decided a change of command was needed. Ghormley was fired and Admiral Bill Halsey took over as C-in-C South Pacific. Aggressive, beloved of his men and a skilled tactician, his appointment came in the nick of time.

At the moment Bill Halsey took over, it was clear the Japanese were preparing a significant naval attack, but first came a major assault by land on Henderson Field on the evening of 24 October. Despite the exhaustion of the Marines, they once again cut down the attacking Japanese over the course of two nights. It was during these attacks that Sergeant John Basilone won the Congressional Medal of Honor, the highest US award for gallantry, for manning, moving and repairing several machine guns and holding his position until replacements arrived.

Out at sea, the biggest naval clash since Midway began on 25 October. Over two days, another bitter battle took place on sea and in the air. Eventually, the Americans withdrew after the loss of the carrier Hornet, and after Enterprise was badly damaged, but the levels of attrition were beginning to bite the Japanese hard. In what became known as the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands, the Japanese lost far too many irreplaceable veteran aircrew – 148 compared with 26 American, and including 23 squadron leaders. The balance of power in the air war in the Pacific had begun gradually but decisively to shift in favour of the Americans.

Meanwhile, the Tokyo Express continued to land more troops – another 20,000 by mid-November – but more troops meant more mouths to feed and equipment to supply, which was beyond Japan’s logistical capabilities. Their men now on Guadalcanal were living off little more than 500 calories a day. It was no way near enough.

General Vandegrift now ordered his Marines on to the offensive, pushing west towards Cruz Point. The Americans’ grip on the island was starting to tighten.

In early November, Allied intelligence learned the Japanese were preparing to land yet more men and supplies, this time with the support of strong naval forces, and then to renew their attack on Henderson Field. Before they could do so, however, the Americans sent more Marines, as well as two army infantry battalions, food and ammunition, escorted by two naval task forces. The men and supplies were unloaded safely just a day before the arrival of the Japanese through the ‘Slot’ – the channel between Guadalcanal and Savo Island – on the night of 13 November. The American warships were badly outclassed by those of the Japanese, but they attacked anyway, in the hope of preventing enemy battleships from hammering the airfield once more. By dawn next day, wreckage littered the waters off Guadalcanal. The Americans had lost two cruisers and four destroyers, but a Japanese battleship, heavy cruiser and two destroyers had been sent to the bottom. More damaging for the Japanese was the loss of seven transport ships with most of the men aboard.

Admiral Halsey sent further reinforcements, including two battleships, and the next night the waters around Guadalcanal were once again alive with the thundering sound of battle. This time, the enemy naval forces were routed. The Japanese force had been the larger but had been defeated by superior gunnery and radar fire-control systems. In the morning, four more transport ships were run aground in a desperate effort to get troops ashore. Only around 2,000 Japanese soldiers were landed before each ship was hit and destroyed. Later, an enemy ammunition dump was spotted in the jungle, and hit with a massive explosion. The Japanese had just lost the battle for Guadalcanal.

Although there were over 30,000 Japanese troops on Guadalcanal, there was now no realistic way of supplying them. Morale deteriorated dramatically as the soldiers starved and became riddled with disease. By December, few more than 4,000 of them were fit enough to fight, as the Americans painstakingly cleared one bunker and tunnel after another.

By the start of February 1943, even the Japanese had had enough and began evacuating the survivors – a mere 10,000 of the 36,000 that had fought there. ‘Hardly human beings,’ wrote one Japanese soldier who saw them, ‘they were just skin and bones dressed in military uniform, thin as bamboo sticks.’ Most of the rest died. By comparison, the Americans lost 5,875 casualties, of whom 1,500 were killed.

The long and bitter struggle for Guadalcanal was finally over on 9 February 1943. It had been a humiliating and war-turning defeat for the Japanese. Technically, they were now standing still, running short of desperately needed resources, while growing numbers of factories in the USA produced ever more ships, tanks and aircraft.

In Arakan in north-west Burma, the British counter-attack was stopped in early 1943, but the Allies had now set up a highly effective air-supply line across the Himalayas from India to China. Suddenly and dramatically, Japan was on the back foot, her incredible early advances halted.

As if to underline this change of fortunes, American cryptanalysts learned that Admiral Yamamoto was flying from Rabaul to the southern end of Bougainville on 18 April. This was just within range of Henderson Field. On Nimitz’s orders, at around 9.45 a.m. his plane was attacked by US P-38 Lightnings, shot down, and Yamamoto killed.

The Japanese news announcer broke down in tears as he announced Yamamoto’s death. ‘There is widespread sentiment,’ wrote one Japanese diarist, ‘of dark foreboding about the future course of the war.’

The end of the Guadalcanal campaign meant future action in the South Pacific moved into General Douglas MacArthur’s agreed area of operations west of the 159th Parallel. Although commanding US Army troops rather than the Marine Corps, MacArthur was still dependent on the US Navy, but fortunately he and Admiral Bill Halsey gelled immediately. Together, they planned a series of leapfrogging operations, drawing on hard-won experience already gained in the Pacific and on the United States’ burgeoning military might.

On 21 February, 10,000 soldiers and marines were landed on the Russell Islands, to the north-west of Guadalcanal. As soon as the islands were secure, Seabees arrived to hack out two more airfields. Nowhere was land, air and sea power more interconnected and mutually essential than here, in the South Pacific.

In the summer, New Georgia was captured; in the autumn, it was Bougainville’s turn, the last of the Solomon Islands to return to Allied control. Earlier, a decision had been made by MacArthur and Halsey to bypass Rabaul entirely. Instead, the town would be pummelled and neutralized by air power, while finally, in December 1943, the 1st Marine Division, recovered after their ordeal on Guadalcanal, stormed the beaches of Cape Gloucester at the north-western end of New Britain. Weakly defended airfields were swiftly secured, while the large number of Japanese troops on the island retreated towards Rabaul and dug themselves in.

Japanese determination never to surrender worked entirely against them on New Britain and around Rabaul as MacArthur and Halsey’s forces seized a ring of islands and bases, effectively cutting them off from the rest of the world. ‘The Americans flowed into our weaker points and submerged us,’ noted one Japanese intelligence officer, ‘just as water seeks the weakest entry to sink a ship.’

Without doubt the Japanese combination of iron discipline and superb training had helped them win a string of stunning victories at the start of the Pacific War. They were, however, extremely inflexible. For Japan, there was only one way of fighting. Once committed to a plan, there could be no turning back; to do so was to admit failure. And failure was both dishonourable and totally unacceptable in the sadistic ultra-nationalistic culture that had evolved in Imperial Japan.

By the end of 1943, some 125,000 Japanese soldiers lay trapped around Rabaul. The pride of the Imperial Japanese Navy had been lost, its carriers pulled back, most of its experienced pre-war naval aviators killed, with more than 2,000 aircraft destroyed, while the next generation of warriors had neither the skills nor training of their predecessors.

In contrast, the United States was growing stronger by the day, and also increasingly battle-hardened. Green they may have been when the Japanese struck Pearl Harbor, but they were quick to absorb the lessons of war. Yet more and better ships, aircraft and weapons were arriving too. ‘We’ve got so much equipment in the Pacific now,’ wrote one officer, ‘it’s like shooting ducks out of your front living room.’

Many hard and terrible battles lay ahead but, in the Pacific, Allied victory was now assured.