This overview of the history of ancient Rome covers the period from the foundation of Rome by Romulus (so legend said) in the eighth century B.C., through the Roman Republic, to the establishment of what we today call the Roman Empire, finishing with the rule of Emperor Justinian in the sixth century A.D. Roman history emphatically did not come to an end with Justinian’s reign, but that period will provide the chronological stopping point for this book. This reflects the (for Romans) regrettable circumstances that made Justinian the last ruler to try to restore the territorial extent and glory of the later Roman Empire, which had shrunk by that emperor’s time to a fraction of the size and might that it had reached at the height of Roman power nearly half a millennium before Justinian’s time. Geographically, the narrative covers the enormous territory in Europe, North Africa, and western Asia (the Middle East) that the Romans ruled at that earlier high point in their power.

As a brief survey, this book necessarily omits a great deal of information about ancient Rome and pays more attention to some topics than others. For example, a fuller survey would describe in more detail the history of the Italian peoples before the traditional date of Rome’s foundation in 753 B.C., whose deeds and thoughts greatly influenced the Romans themselves. Likewise, a longer book would explore the history of the Roman world after Justinian, when the emergence of Islam changed forever the political, cultural, and religious circumstances of the Mediterranean world that the Roman Empire once dominated. The books listed in the Suggested Readings section provide further discussion and guidance on many topics that receive little or no coverage here.

In my experience teaching Roman history for nearly forty years, if readers are willing to do the hard work required to participate in the fascinating and still-ongoing conversation about interpreting what Romans did and said and thought, the best thing that they can do for themselves is to read the ancient sources—more than once! For this reason, citations in parentheses direct readers to ancient sources quoted in the text, most of which also appear in the Suggested Readings section. In this way I hope to encourage readers to read the primary sources for themselves, so that they can experience the contexts of the evidence, discover what in particular interests them in the ancient texts, and on the basis of their further reading arrive at independent judgments on the significance of events and persons and ideas in Roman history. In the service of this same goal, the first two sections in the Suggested Readings are devoted to currently available translations of ancient sources that are either explicitly mentioned in the text or lie behind discussions in the text, even if the particular sources are not mentioned there.

In any case, to follow the rest of the story the reader needs to know in advance some basic facts of Rome’s history: its main chronological divisions;, the main sources on which our knowledge of it is based; long-term themes with which we will be concerned; and something of the Romans’ “prehistory”—the Romans’ Italian forerunners, and the neighbors whose early influence helped set the direction of Rome’s cultural development, the Etruscans and the Greeks.

This book follows the usual three-part chronological division of Roman history—Monarchy, Republic, and Empire (on which terms see below). It is important to make clear, however, that categorizing Rome’s history under these three periods is an anachronistic practice. For the Romans, there was only one significant dividing point in their history: the elimination of the rule of kings at the end of the sixth century B.C. After the monarchy was abolished, the Romans themselves never stopped referring to their political system as a Republic (res publica, “the people’s thing, the people’s business”), even during the period that we call the Empire, which begins at the end of the first century B.C. with the career of Augustus. Today, Augustus is called the first Roman emperor; the Romans, however, referred to him as the princeps, the “First Man” (of the restored and continuing Republic). This is the political system that is usually called the Principate. The Romans certainly realized that Augustus’s restructuring of the Roman state represented a turning point in their history, but all the “emperors” (in our terms) who followed him continued to insist that their government remained “the Republic.”

The three time periods do not receive equal treatment in this book. The history of the Monarchy is presented much more briefly than the histories of the Republic and the Empire. This reflects above all the relative lack of reliable evidence for the time of the kings of Rome (although the evidence for the early Republic is hardly much better). The Republic and the Empire, on the other hand, receive roughly equal coverage. Only limited space is devoted to wide-ranging explanations of events and people in ancient Rome and judgments concerning the significance of Roman history for later times. This does not mean that I do not have strong opinions about these issues or that I believe the story “speaks for itself.” Here, my goal is to present the story in such a way that it encourages readers to take on the difficult job of deciding for themselves why the Romans acted and thought as they did, and what meanings to attribute to the history of ancient Rome.

In the first of the three customary periods of Rome’s political history, a series of seven kings ruled from 753 to 509 B.C., according to the traditionally accepted chronology. These dates are in fact only approximate, like most dates in Roman history until at least the third century B.C. (and in many cases for later centuries as well). The Republic, a new system of shared government replacing a sole ruler, extended from 509 to the second half of the first century B.C. In this overview, the end of the Republic is set in 27 B.C., the date when Augustus established the Principate (the government that modern historians call the Roman Empire).

The period of the Empire then follows. The last Roman emperor in the western half of the empire (roughly speaking, Europe west of Greece) was deposed in A.D. 476; this date has therefore sometimes been taken to mark “The Fall of the Roman Empire.” However, the narrative here takes the history of the empire roughly a century beyond this “Fall,” reaching the reign of Justinian (A.D. 527–565) in the eastern empire.

As far as the people of the eastern section of the empire were concerned, Roman imperial government continued for another thousand years, with Constantinople as the capital, the empire’s “New Rome.” The last eastern emperor was killed in A.D. 1453, when the Turkish commander Mehmet the Conqueror captured Constantinople and what little was left of the territory of the eastern Roman Empire. Historians today call the empire that Mehmet founded the Ottoman Empire. Since the Ottomans took over the remaining territory of the Eastern Roman Empire, this date might qualify as a better choice for the Roman Empire’s “Fall” than A.D. 476. It is worth remembering, however, that Mehmet publicly announced that as a ruler he was building on (and aiming to outdo) the legacies of Alexander the Great, the Macedonian conqueror, Julius Caesar, and Augustus, whose accomplishments he had read about in Greek and Latin historical sources. Mehmet in fact proclaimed that his title was “Caesar of Rome.” In other words, the first Turkish emperor was not seeking to end Roman history, but to redefine and extend it. In Russia, the idea soon began to be expressed that its empire was the “Third Rome.” In the same spirit of emulation of the remembered glory of ancient Rome, around this time Frederick III proclaimed that he, too, was a Roman emperor, like his predecessors who had ruled the central European territories long known as the Holy Roman Empire. It is clear, then, that the memory of the glory of ancient Rome proved so seductive to later rulers that its history lived on in influential ways even after the empire’s “Fall,” regardless of how that concept is understood or what date historians give to it.

The sources of information for Roman history are varied. There are first of all the texts of ancient historical writers, supplemented by the texts of authors of other kinds of literature, from epic and lyric poetry to comic plays. Documentary evidence, both formal and informal, survives as inscriptions carved, inked, or painted on stone, metal, and papyri. Archaeological excavation reveals the physical remains of buildings and other structures, from walls to wells, as well as coins, manufactured objects from weapons to jewelry, and traces of organic materials such as textiles or food and wine preserved in storage containers. Roman art survives in sculptures, paintings, and mosaics. In sum, however, despite their variety, the sources that have survived are too limited to allow us a view of the events, ideas, and ways of life of ancient Rome that is anywhere near as full as the panoramic reconstruction of the past that historical research on more recent periods can achieve.

In addition, in Roman history (as in all ancient history), the exact dates of events and of the lifetimes even of important people are often not accurately recorded in our surviving sources. Readers should therefore recognize that many dates given here are imprecise, even if they are not qualified as “around such and such a year.” Indeed, it is best to assume that most dates given here, especially for the opening centuries of Roman history, are likely to be approximations at best and subject to debate among professional historians.

For all these reasons, Roman history remains a story characterized by uncertainties and controversies. Readers should therefore understand that the limited interpretations and conclusions offered here should always be imagined to be followed by the thought that “we might someday discover new evidence, or use our historical imaginations to arrive at new interpretations of currently known evidence, and then change our minds about this particular interpretation or conclusion.”

The evidence for the early history of Rome is the most limited of all. The two most extensive narrative accounts of Roman history under the Monarchy and the Republic that have survived (at least in part) were not written until seven centuries after the city’s foundation. In addition, the manuscripts on which we today depend for these texts are missing substantial parts of the original narratives. One of these primary ancient sources is the From the Foundation of the City by Livy (59 B.C.–A.D. 17), a Roman scholar with no career in war or politics who narrated Rome’s history from its earliest days down to his own time.

The other extended narrative covering the early history of Rome is by Dionysius of Halicarnassus, a Greek scholar who lived in Rome as a foreigner making his living as a teacher. He wrote his history, Roman Antiquities, at about the same time as Livy, toward the end of the first century B.C. These authors tended to interpret the long-past era of early Rome as a golden age compared to what they saw as the moral decline of their own times, a period of civil war when the system of government known as the Roman Republic was being violently transformed into a disguised monarchy under the rule of Augustus, the system of government today known as the Roman Empire. When, for instance, Livy in the preface to his Roman history refers to this era—his own lifetime—he sadly calls it “these times in which we can withstand neither our vices nor the solutions for them.”

The surviving textual sources become more numerous for the later history of the Republic; in addition to Livy and Dionysius (and to name only the best-known that are readily available in English translation), there are Polybius’s Histories on the late third and early second centuries B.C., including famous descriptions of the Roman army and what modern scholars sometimes call the “mixed constitution” of the government of the Republic, seen as a combination of monarchy, oligarchy, and democracy. For the late second and first centuries, there are vivid narratives and personal reflections on and by major historical figures in Sallust’s War with Jugurtha and Conspiracy of Catiline, Julius Caesar’s Commentaries on the Gallic War and Commentaries of the Civil War, Cicero’s Orations and Letters, and Appian’s Civil Wars. Plutarch’s Parallel Lives offers numerous lively biographies of the most famous leaders of the Roman Republic, from Romulus to Julius Caesar.

The textual sources of our information about the Roman Empire, despite being more extensive than for earlier periods, are also incomplete. The best known ancient authors whose works provide much of what we know about this period of history include Suetonius’s Lives of the Twelve Caesars (biographies of Julius Caesar and the Roman emperors from Augustus to Domitian); Tacitus’s narratives of imperial history in the first century A.D., the Annals and the Histories; Josephus’s The Jewish War, an eyewitness account of the rebellion of the Jews and of the Roman military action that led to the destruction of Jerusalem in A.D. 70; Cassius Dio’s Roman History, which narrates Roman history up to the early third century A.D.; Ammi-anus Marcellinus’s Roman History, narrating the history of the fourth century A.D.; and Procopius’s narratives of the reign of Emperor Justinian and Empress Theodora in the sixth century A.D., History of the Wars and Secret History, the former account full of praise and the latter fiercely critical. Orosius’s Seven Books of History against the Pagans gives a Christian version of universal history, including the Roman Empire up to the early fifth century A.D.

By the time of the later Roman Empire, a great preponderance of the surviving evidence pertains to the history of Christianity. This salient fact reflects the overwhelming impact on the Roman (and later) world of the growth of the new faith, and it necessarily influences the content of any narrative of that period.

The ancient authors’ points of views on Roman life and government during the period of the Empire vary too widely to be clearly summarized without distortion, but it is perhaps fair to say that over time a nostalgic sense of regret for the loss of the original Republic and its sense of liberty (at least for those in the upper class) gave way to a recognition that an empire under a sole and supreme ruler was the only possible permanent system of government for the Roman world. This acceptance of the return of monarchs as Rome’s rulers nevertheless also reflected, for many Romans, anger and regret at the abuses and injustices committed by individual emperors.

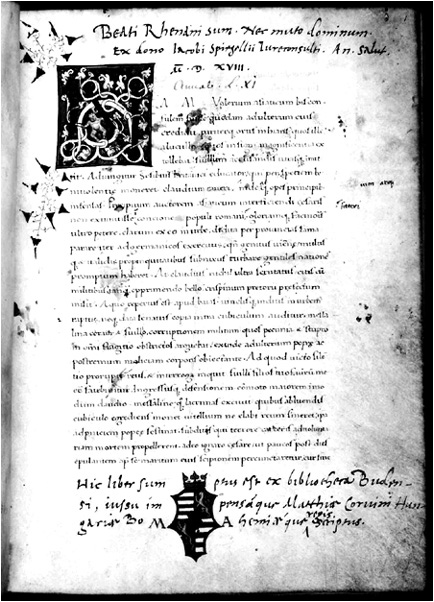

Figure 1. This Renaissance-era manuscript of Tacitus’s Annals is better preserved than most of the manuscripts on which we rely for texts of ancient authors. Tacitus’s emphasis on politics in his narrative of the history of the early Roman Empire inspired a lively debate among Renaissance political theorists about the relative merits of a republic versus a monarchy. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

In my experience, a preliminary “flyover” helps readers who are new to ancient history comprehend the more detailed narrative that follows. All the terms used here will be explained subsequently at the appropriate places.

The ethnic and cultural origins of the ancient Romans reflect both their roots in Italy and also contact with Greeks. The political history of Rome begins with the rule of kings in the eighth century B.C.; the Romans remembered them as founders of enduring traditions in society and religion, but the limited information available from the surviving sources makes it difficult to know much in detail about this period. The Romans also reported that the monarchy was abolished at the end of the sixth century B.C. in response to the violent rape of a prominent Roman woman by the king’s son. The kingship was then replaced by the Republic, a complicated system of shared government dominated by the upper class.

The greatest challenge in studying the Roman Republic is to understand how a society based on a long tradition of ethical values linking people to one another in a patron-client system (a social hierarchy with mutual obligations between those of higher and lower status) and with a successful military could eventually fail so spectacularly. From its beginnings, the Republic had grown stronger because the small farmers of Italy could produce an agricultural surplus. This surplus supported a growth in population that produced the soldiers for a large army of citizens and allies. The Roman willingness to endure great losses of people and property helped to make this army invincible in prolonged conflicts. Rome might lose battles, but never wars. Because Rome’s wars initially brought profits, peace seemed a wasted opportunity. Upper-class commanders especially desired military careers with plenty of combat because, if they could win victories, they could win also glory and riches to enhance their status in Rome’s social hierarchy.

The nearly continual wars of the Republic from the fifth to the second centuries B.C. had unexpected consequences that spelled disaster in the long run. Many of the small farmers on whom Italy’s prosperity depended were ruined. When those families that had lost their land flocked to Rome, they created a new, unstable political force: the urban mob subject to the violent swings of the urban economy. The men of the upper class, on the other hand, competed with each other harder and harder for the increased career opportunities presented to them by constant war. This competition reached unmanageable proportions when successful generals began to extort advantages for themselves from the state by acting as patrons to their client armies of poor troops. The balance of ethical values that Roman mothers tried to teach their sons was being shattered in these new conditions, and lip service was the only respect that traditional values supporting the community received from nobles mad for individual status and wealth. In this superheated competitive atmosphere, violence and murder became a means for settling political disputes. But violent settlements provoked violent responses. The powerful ideas of Cicero’s ethical philosophy went ignored in the murderous conflicts of the civil war of his own times. No reasonable Roman could have been optimistic about the chances for an enduring peace in the aftermath of Julius Caesar’s assassination. That Augustus, the adopted son of Caesar, would forge such a peace less than fifteen years later would have seemed an impossible dream in 44 B.C.

History is full of surprises, however. Augustus created what we today call the Roman Empire by replacing the shared-government structure of the Republic with a monarchy, while insisting all the while that he was restoring Roman government to its traditional values. He succeeded above all because he retained the loyalty of the army and exploited the ancient tradition of the patron-client system. His new system, the Principate, made the emperor the patron of the army and of all the people. Most provincials, especially in the eastern Mediterranean, found this arrangement perfectly acceptable because it replicated the relationship between the monarch and his subjects that they had long experienced under the kingdoms that had previously ruled them.

So long as there were sufficient funds to allow the emperors to keep their tens of millions of clients across the empire satisfied, stability prevailed. The rulers spent money to provide food to the poor, build arenas and baths for public entertainment, and paid the soldiers to defend the peace internally and against foreign invaders. The emperors of the first and second centuries A.D. expanded the military by a third to protect their distant territories stretching from Britain to North Africa to Syria. By the second century, peace and prosperity had created an imperial Golden Age. Long-term financial difficulties set in, however, because the army, now focused on defense instead of conquest, no longer fought and won foreign wars that brought money into the treasury. Severe inflation made the situation worse. The decline in imperial revenues imposed intolerable financial pressures on the wealthy elites of the provinces to ensure full tax payments and support public services. When they could no longer meet this demand without ruining their fortunes, they lost their public-spiritedness and began avoiding their communal responsibilities. Loyalty to the state became too expensive.

The emergence of Christians added to the uncertainty by making officials suspicious of the new believers’ dedication to the state and its traditional religion. This new religion started slowly with the mission of Jesus of Nazareth, and evolved from Jewish apocalypticism to an institutionalized and hierarchical church. Christianity’s believers disputed with each other and with the authorities. Their martyrs both impressed and concerned the government with the depth of their convictions during persecutions. People placing loyalty to a new divinity ahead of traditional loyalty to the state was unheard-of and inexplicable for Roman officials.

When financial ruin, civil war, and natural disasters reinforced each other’s horrors in the mid-third century A.D., the emperors lacked the money, the vision, and the dedication to communal values that might have alleviated, or at least significantly lessened, the crisis. Not even persecutions of the Christians could convince the gods to restore divine good will to the empire. It had to be transformed politically and religiously for that to happen.

The process of once again reinventing Roman government began at the end of the third century. The subsequent history of the late Roman Empire was a contest between the forces of unity and the forces of division. The third-century A.D. crisis brought the Roman Empire to a turning point. Diocletian’s autocratic reorganization kept it from falling to pieces in the short term but opened the way to its eventual division into western and eastern halves. From this time on, its history more and more divided into two regional streams, even though emperors as late as Justinian in the sixth century A.D. retained the dream of reuniting the Roman Empire of Augustus and restoring its glory on a scale equal to that of its Golden Age.

A complex of forces interacted to destroy the unity of the Roman world, beginning with the catastrophic losses of people and property during the crisis, which had hit the west harder than the east. The fourth century A.D. introduced a new stress with the pressures on central government created by the migrations of Germanic peoples fleeing the Huns. Too numerous and too aggressive to be absorbed without disturbance, they created kingdoms that eventually replaced imperial government in the western empire. This change transformed not just western Europe’s politics, society, and economy, but also the Germanic tribes themselves, as they had to develop a stronger sense of ethnic identity to become rulers.

The economic deterioration accompanying these transformations drove a stake into the heart of the elite’s public-spiritedness that had been one of the foundations of Roman imperial stability, as super-wealthy nobles retreated to self-sufficient country estates, shunned municipal office, and ceased guaranteeing tax revenues to the central government. The eastern empire fared better economically and avoided the worst of the migrations’ violent effects. Its rulers self-consciously continued the empire not only politically but also culturally by seeking to preserve “Romanness.” The financial drain of pursuing this dream of unity through war against the Germanic kingdoms in the west ironically increased social discontent by driving tax rates to punitive levels, while the concentration of power in the capital weakened the local communities that had made the empire robust.

This period of increasing political and social division saw the religious unification of the empire under the banner of Christianity. The emperor Constantine’s conversion to the new faith in the early fourth century A.D. marked an epochal point in the history of the world, though the process of Christianizing the Roman Empire had much longer to go at this date. Moreover, this process was far from simple or swift: Christians disagreed, even to the point of violence, over fundamental doctrines of faith, and believers in traditional Roman polytheistic religion continued to exist and worship for centuries more. Christians developed a hierarchy of leadership in their emerging church to try to prevent disunity, but believers proved remarkably recalcitrant in the face of authority. The most dedicated of them abandoned everyday society to live as monks and nuns. Monastic life redefined the meaning of holiness by creating communities of God’s heroes withdrawing from this world to devote their valor to glorifying the next. In the end, then, the imperial vision of unity faded before the divisive forces of the human spirit combined with the mundane dynamics of political and social transformation. What remained was the memory of the past, encoded in the literature from classical antiquity that survived the many troubles of the time of the later Roman Empire.

To understand the people and the events of this history, we must begin, as always in historical study, with the geography and environment in which it took place. The location of Rome provides the fundamental clue in solving the puzzle of how this originally tiny, poor, and disrespected community eventually grew to be the greatest power in enormous regions surrounding the Mediterranean Sea. Rome’s geography and climate helped its people, over a long period of time, to become more prosperous and powerful. Their original territory, located on the western side of the center of the north-south peninsula that is Italy, provided fertile farmland, temperate weather with adequate rainfall, and a nearby harbor on the Mediterranean. Since agriculture and trade by sea were the most important sources for generating wealth in ancient times, these geographical characteristics were crucial to Rome’s long-term growth.

The landscape of Italy is diverse: its plains, river valleys, hills, and mountains crowd into a narrow, boot-shaped tongue of land extending far out into the waters of the Mediterranean. At the north, the towering Alps Mountains divide Italy from continental Europe. Since these snowy peaks are so difficult to cross, they provided some protection from invasions launched by raiders living north of the Alps. A large and rich plain, watered by the Po River, lies at the top of the Italian peninsula just south of the Alps. Another, lower chain of mountains, the Apennines, separates the northern plain from central and southern Italy. The Apennines then snake southeastward, down the middle of the peninsula like a knobby spine, with hills and coastal plains flanking the central mountain chain on the east and west. The western plains, where Rome was located, were larger and received more rainfall than the other side of the peninsula. An especially fertile area, the plain of Campania, surrounds the bay of Naples on Italy’s southwestern coast. Italy’s relatively open geography made political unification a possibility.

The original site of the city of Rome occupied hilltops above a lowland plain extending to the western coast of the peninsula. The various Italian peoples neighboring Roman territory were more prosperous than the first Romans; archaeological investigation has revealed that the earliest Romans lived in small huts. Their settlement, gradually extending over seven hills that formed a rough circle around a low-lying central area, had an advantage, however, because it controlled a crossing of the Tiber River. This setting on a crossroads encouraged trade and contact with other people crossing the river as they journeyed up and down the natural route for northwest-southeast land travel along the western side of Italy. The harbor at Ostia, at the mouth of the Tiber River only fifteen miles west of Rome, offered opportunities for contact with people much farther away, profit from overseas trade, and fees and other revenues from seaborne merchants stopping there—Italy stuck so far out into the Mediterranean Sea that east-west ship traffic naturally relied on its harbors. In addition, the large and fertile island of Sicily right off the “toe” of the Italian peninsula also attracted sea-going merchants who could from there easily travel up and down the western coast doing business. In short, geography put Rome at the natural center of both Italy and the Mediterranean world, giving it, in the long run, tremendous demographic and commercial advantages. Livy summed up Rome’s fortunate location with these words: “Gods and men had good reason to choose this site for our city—all its advantages make it of all places in the world the best for a city destined to grow great” (From the Foundation of the City 5.54).

Map 1. Italy Around 500 B.C.

Demography (the statistical study of human populations) rivals geography as a tool for understanding how Rome grew powerful in the long run. History shows that the larger a population, the greater its chances to gain prosperity and power, including ruling other, smaller populations. Nature gave the Romans the means to grow in population and wealth that the Greeks could never equal: Italy’s level plains were better for agriculture and raising animals than was the heavily mountainous terrain of Greece. Italy could therefore house and feed more people than Greece. Of course, in the beginning, the Romans amounted only to a tiny community surrounded by frequently hostile neighbors. The base of Roman history is the story of how they expanded their population from that puny start to the tens of millions (the exact number is controversial) of the time of the Roman Empire.

The later Romans had many legends about their ancestral origins as a small population fighting the odds to survive in a hostile world. They highly respected that distant past as the source for the traditions and values by which they guided their lives. It is therefore frustrating to report that little reliable evidence survives to tell us about their ancestors. Linguistic investigation has shown that the Romans descended from earlier peoples who spoke Indo-European languages (of which English is one modern example). The Indo-Europeans organized their societies according to rankings of people in a hierarchy of status and privilege, with men as political leaders and the heads of families. These “proto-Romans” had migrated to Italy from continental Europe at an unknown date many, many centuries before the foundation of Rome. The Romans’ ancestors had therefore lived in northern and central Italy for a very long time before the foundation of Rome. Some Romans at least believed that their ancestors had a more romantic identity: Dionysius reports that the Romans were descended from heroic Trojans who escaped their burning city at the end of the Trojan War, emigrating from Troy to Italy four hundred years before Rome’s foundation.

Our main evidence for the Romans’ immediate ancestors comes from archaeological excavation of graves dating to the ninth and eighth centuries B.C. Since we do not know what the people buried in these graves called themselves, scholars have usually referred to them as Villanovans, a term taken from the modern name of the location of the first excavation. In fact, there is no reason to think that these peoples, who lived in various different communities, thought of themselves as a unified group. What archaeology does reveal is that they farmed, raised horses, and forged metal weapons and many other objects from bronze and iron. Since bronze is a mixture of copper and tin, and since tin was only mined in locations far from Italy, these Roman ancestors engaged in long-distance trade.

By the eighth century B.C., the Romans and the other peoples of central and southern Italy had frequent contact with Greek traders voyaging to Italy by sea, and this originally commercial interaction had a significant impact on Roman society and culture. Many Greek entrepreneurs settled permanently in southern Italy in this period, seeking riches as immigrant farmers and traders. Many of these risk-takers succeeded, and numerous cities mainly populated by Greeks became important communities in Italy, from Naples to the southern regions of the peninsula, as well as nearby Sicily. The diverse population of that island also included Phoenicians originally from the eastern Mediterranean coast.

The Romans’ contact with Greek culture had the greatest effect on the development of their own ways of life. Greek culture reached its most famous flowering by the fifth century B.C., centuries before Rome had its own literature, theater, or monumental architecture. When the Romans eventually began to develop these cultural characteristics, they took Greek models as inspiration. They adopted many fundamental aspects of their own ways from Greek culture, ranging from ethical values to deities for their national cults, from the models for their literature to the architectural design of large public buildings such as temples. Nevertheless, Romans had a love-hate relationship with Greeks, admiring much of their culture but looking down on Greece’s political disunity and military inferiority to Rome.

The Romans also adopted ideas and cultural practices from the Etruscans, a people located north of Rome in a region of central Italy called Etruria. The extent of Etruscan cultural influence on Rome is controversial. Scholars have often thought of the Etruscans as the most influential outside force affecting the Roman way of life. Some have even speculated that Etruscans conquered early Rome, with Etruscan kings ruling the new city during the final part of the monarchy that was its first government. In addition, since early scholars rated the Etruscans as more culturally refined than early Romans (mainly because archaeologists had discovered so many Greek painted vases in Etruscan tombs), they assumed that these supposedly more sophisticated foreign rulers had completely reshaped Roman culture. More recent scholarship suggests that this interpretation is at the very least overstated. The truth seems to be that the Romans developed their own cultural traditions, borrowing whatever ways appealed to them from Etruscan and Greek culture and then adapting these foreign models to Roman circumstances.

Figure 2. Paestum was one of the numerous Greek cities in southern Italy and Sicily that had magnificent stone temples of the gods. The state of preservation of Paestum’s three adjacent temples rivals that of any site in Greece. Courtesy of Dr. Jesus Oliver-Bonjoch.

Our knowledge of the Etruscans’ origins remains limited because we only partly understand their language. We do not know to what group of languages it belonged, but it was probably not Indo-European. The fifth-century B.C. Greek historian Herodotus believed that the Etruscans had originally immigrated to Italy from Lydia in Anatolia, but Dionysius of Halicarnassus reported that Italy had always been their home, the predominant view today.

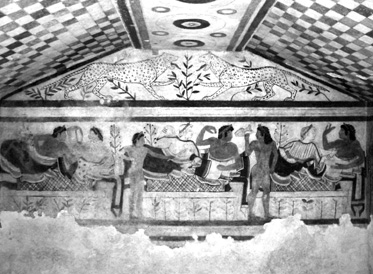

The Etruscans were not a unified ethnic group or political nation; they lived in numerous independent towns nestled on central Italian hilltops. They produced their own fine art work, jewelry, and sculpture, but they spent large sums to import many luxury objects from Greece and other Mediterranean lands. Above all, the Etruscans had close contacts with Greece and adapted much from Greek culture to their own way of life. For example, most of the intact Greek vases found in modern museums were discovered in Etruscan tombs, where they had been placed to accompany the dead by the Etruscan families that had purchased them. Magnificently colored wall paintings, which still survive in some Etruscan tombs, portray games, entertainments, and funeral banquets testifying to a vivid social and religious life.

Figure 3. A painting from an Etruscan tomb depicts dinner guests reclining in the Greek fashion and being attended by servants. The bright primary colors of scenes painted in Etruscan tombs reveal the characteristic style of Greek painting, of which few examples have survived in its homeland. AlMare/Wikimedia Commons.

The Romans adopted certain ceremonial traditions from the Etruscans that persisted for centuries, such as the elaborate costumes worn by magistrates, as well as musical instruments and procedures for important religious rituals. It is no longer seen as accurate, however, to think that Romans also took from the Etruscans the tradition of erecting temples divided into three sections for worshipping a triad of main gods. It was a native Roman tradition to worship together Jupiter, the king of the gods, Juno, the queen of the gods, and Minerva, the goddess of wisdom, deities whom they and the Etruscans had taken over from the Greeks. On the other hand, the Romans did learn from the Etruscans their ritual for discovering the will of the gods by looking for clues in the shapes of the vital organs of slaughtered animals, a process known as divination. The Romans probably also adopted from Etruscan society the tradition of women joining men for dinner parties, which the Greeks restricted to men only. Tomb paintings, for instance, confirm what the Greek philosopher and scientist Aristotle reported: Etruscan women joined men at banquets on an apparently equal footing (Athenaeus, The Learned Banqueters 1 23d = Constitution of the Tyrrhenians fragment 607 Rose). In Greek society, the only women who ever attended dinner parties with men were courtesans, hired musicians, and slaves.

Other Roman developments that some scholars attribute to Etruscan influence were in fact characteristic of various societies around the Mediterranean at this time. This fact suggests that these characteristics were part of the shared cultural environment of the region and not specifically Etruscan in origin. Thus Rome’s first political system, the monarchy, resembled Etruscan kingship, but this form of rule was so common in the world of the early Mediterranean, indeed the norm, that it was not something the Romans could only have learned from their near neighbors. For the same reason, the organization of the Roman army—a citizen militia of heavily armed infantry troops (hoplites) fighting in formation—could reflect Etruscan influence, but other Mediterranean peoples organized their militaries in the same way. The Romans adapted their alphabet (which forms the basis of the English alphabet) from the Etruscan alphabet, but that alphabet was in turn based on a version of that kind of writing system that the Greeks had created as a result of their contact with the earlier alphabets of eastern Mediterranean peoples. Finally, scholars have claimed that the Romans learned from the Etruscans how to conduct long-distance trade with other areas of the Mediterranean, which promoted economic growth, and sound civil engineering, which supported urbanization. But it is simplistic to assume that cultural developments of this breadth emerged as the result of a single superior culture “instructing” and “improving” another, less developed culture. Rather, at this time in Mediterranean history, there were similar sets of cultural developments under way in many places.

Cross-cultural contact with their neighbors had a significant influence on the Romans. However, the Romans did not take over the traditions of other cultures in some simple-minded way or change them only in superficial ways, such as giving Latin names to Greek gods. Rather, as always in cross-cultural influence, whatever people take over from other people they adapt to their own purposes—they change it to suit themselves and in this way make it their own. It is more accurate to think of cross-cultural contact as a kind of competition in innovation between equals than as a “superior” tutoring an “inferior.” Cultural development is a complex historical process, and historians only reveal the poverty of their own understanding if they speak of one ancient culture’s dominance over another or the corruption of a “primitive” culture by an “advanced” one. The Romans, like other peoples, developed their own ways of life through a complex process of independent invention and adaptation of the ways of others.