Romans believed that their community first took shape under the rule of kings in the eighth century B.C. The surviving sources are full of colorful stories whose accuracy is controversial and difficult to evaluate. Most historians today conclude there is little that we can know for certain about the events in this formative period of Roman history. It is clear nevertheless that the legends about the monarchy reveal important ideas that later Romans held about their origins. These ideas in turn help explain how Romans structured society and politics under the Republic, the system that emerged after the monarchy was overthrown at the end of the sixth century B.C.

Since the Romans for the rest of their history referred to their government as a Republic, even after monarchy had been restored under the Empire, it is crucial to understand the constituent parts of that system and their relationship to the values that characterized Roman ways of life. Those parts were above all the elected officials and voting assemblies that historians often call the “Roman constitution,” even though ancient Rome had no written document like the U.S. Constitution to specify the political structure and powers of government. Under the “Roman constitution,” powers and responsibilities overlapped among governmental institutions, or were divided among them in complex ways.

Ninth/eighth centuries: Villanovans, Greeks, and Etruscans flourish in Italy.

753: Romulus founds Rome as its first king.

716: Romulus dies under mysterious circumstances.

715–673: Numa Pompilius is king, establishing public religious rituals and priest-hoods.

578–535: Servius Tullius is king, organizing the citizens into political and military groups and establishing the practice of granting citizenship to freed slaves.

Mid-sixth century: Rome has expanded to control about 300 square miles of territory in central Italy and creates the Forum in the center of the city.

509: Following Lucretia’s rape and suicide, Brutus and other members of the elite abolish the monarchy and establish the Republic.

479: The Fabius family assembles its own army to wage war for Rome against the Etruscan town of Veii.

458: Cincinnatus serves as dictator to save Rome in a military emergency and immediately returns to private life.

Fifth/fourth centuries: The Struggle of the Orders between patricians and plebeians creates political and economic turmoil.

451–449: The Twelve Tables, the first written code of Roman laws, emerges as a compromise between patricians and plebeians.

337: The plebeians force passage of a law opening all political offices to both orders.

287: Patricians agree that proposals passed in the Tribal Assembly will be official laws, ending the Struggle of the Orders.

The Romans’ technical term for their political community as a whole was “the Roman People” (populus Romanus), but in reality it was not the democracy that this term implies. The upper class always dominated Roman government. Therefore, before describing the officials and assemblies of the Republic, it is necessary to sketch the two-part division of Roman society into legally defined classes, the patricians and the plebeians, and how an upper class of patricians and well-off plebeians gradually and violently emerged as the dominant force in Roman society and politics. This background on the formal structuring of social status is required in particular to understand the nature of the consuls and the Senate, the so-called “ladder of offices” that well-off Roman men aspired to climb as elected officials of government, and, finally, Rome’s complicated voting assemblies.

Modern archaeology, as we saw, shows that Villanovans, Greeks, and Etruscans influenced the Romans as they developed their own cultural identity as part of a wider Mediterranean world. Ancient Roman legend also linked the early Romans to others, in particular the Trojans, but it also emphasized the separateness of the tiny settlement in central Italy that was remembered as the origin of Rome as a state. As Livy’s narrative (From the Foundation of the City 1.5–7) explained, Romulus and his brother Remus originally founded the city in 753 B.C. The story included the grim report that Romulus became the first and sole king after murdering his brother Remus during bitter arguments over the location for Rome and sharing its rule (see also Dionysius, Roman Antiquities 1.85–87). This tale taught Romans that monarchy led to murder by rivals for power. Therefore, the legend that Romans remembered about the origins of their city reminded them just how dangerous disputes over the best political system could become.

The legend also said that after ruling for thirty-seven years Romulus permanently disappeared in 716 B.C. in the blinding swirl of a violent thunderstorm. The mysterious loss of their monarch angered the majority of early Rome’s population because they suspected that Romulus’s circle of upper-class advisers had murdered the masses’ beloved leader and hidden his corpse. To prevent a riot, a prominent citizen shouted out this explanation to the angry crowd: “Romulus, the father of our city, descended from the sky at dawn this morning and appeared to me. In awe and reverence I stood before him, praying that it would be right to look upon his face. ‘Go,’ Romulus said to me, ‘and tell the Romans that, by the will of the gods, my Rome shall be capital of the world. Let them learn to be soldiers. Let them know, and teach their children, that no power on earth can stand against Roman arms.’ When he had spoken these words to me, he returned to the sky” (Livy, From the Foundation of the City 1.16). The speech calmed the people because they now felt assured of their founder’s immortality and their divinely favored destiny. Despite the reconciliation with which it ended, this story showed that conflict between the small number of elite Romans and the mass of ordinary Romans had been part of their history from the beginning.

This story brilliantly summed up the truth about the way in which later Romans viewed the lessons of their history: if the people were brave, maintained their traditions over the generations, and followed the guidance of the upper class, then the gods would favor Rome and ensure that Roman military might would rule the world. At the same time, it also made clear the distrust that ordinary citizens felt toward the upper class. Finally, it also showed that the masses were content to be ruled by a king and knew that the upper class hated the monarchy for the power that it held over even them, no matter how elite they might be. This legend, then, communicated an enduring truth about Roman society: although Romans agreed that they had a special destiny to rule others by conquest, the upper and lower classes held radically different attitudes about what sort of government they believed to be best, creating a fundamental and lasting disagreement about how to structure official power as it affected people’s lives.

Rome at its foundation faced a great challenge to its survival because its population was small and poor compared to its stronger neighbors. The other peoples in the area in which Rome was located, called Latium, were mostly poor villagers themselves, but some of the neighboring settlements were much more populous and more prosperous. Most of the peoples in Latium spoke the same language as the Romans, an early form of Latin, but this linguistic kinship did not mean that these neighboring communities saw themselves as ethnically united. Likewise, the non–Latin-speaking peoples in the region had no inherited reason to respect the existence of the Romans. In this world, every community had to be ready to defend itself against attacks from neighbors.

Counting Romulus as the first king, seven monarchs ruled Rome one after the other for two and a half centuries after the foundation. Rome under the rule of the kings slowly became a larger settlement better able to protect itself by adopting a two-pronged strategy for population growth: absorbing others into its population, or making alliances with them to cooperate militarily. This strategy formed the basis of Rome’s long-term expansion: make outsiders into Romans, or cooperate with them on mutual defense. Incorporating outsiders into the citizen body to become more powerful and prosperous was a necessity for survival for a community like early Rome that began so weak and small. It was also a tremendous innovation in the ancient world. Neither Greeks nor any other contemporary society had this policy of inclusion of foreigners. In fact, nonlocals could almost never become citizens in a Greek state. Greeks employed new citizenship as a way to honor rich foreigners who had benefited the community and had no need or intention of becoming an everyday citizen.

Rome’s unique and innovative policy of taking in outsiders to increase the number of its citizens and thereby strengthen itself was the long-term secret to its eventually becoming the most powerful state the world had yet seen. The policy was so fundamental that Rome even offered slaves a chance for upward social mobility. Romans were slave owners, like every other ancient society. They regarded slaves as their owners’ property, not as human beings with natural rights. Therefore, it is an extraordinary feature of Roman society that slaves who gained their freedom immediately became Roman citizens. People became slaves by being captured in war, being sold on the international slave market by raiders who had kidnapped them, or being born to slave mothers. Slaves could purchase their freedom with earnings that their masters let them accumulate to encourage hard work, or they could be granted freedom as a gift in their owners’ wills. Freed slaves had legal obligations to their former owners as clients, but these freedmen and freedwomen, as they were officially designated, otherwise had full civic rights, such as legal marriage. They were barred from being elected to political office or serving in the army, but their children became citizens of Rome with full rights. In other Mediterranean states, the best that ex-slaves and their offspring could hope for was to become legal aliens with the right of residence, but without citizenship or any hope of obtaining that status and the protections and privileges it carried. Rome’s policy was firmly different, to the state’s great advantage.

As usual for any aspect of Rome’s culture that called for justification, there was a legend to provide an ancient origin for this extremely unusual policy of inclusion of outsiders. Both Livy (From the Foundation of the City 1.9–13) and Dionysius (Roman Antiquities 1.30–32, 38–46) preserve stories that reminded Romans why they needed to take in others if their state was to survive and thrive in a threatening world. Romulus, the legend reported, realized that Rome after its foundation was not going to be able to grow or even preserve itself because it lacked enough women to bear the children needed to increase the population and therefore strengthen the community. So he sent representatives to Rome’s neighbors to ask for the right for its men, regardless of their poverty, to marry women from these nearby communities. (In the ancient world this kind of intermarriage was usually available only to prosperous families.) He instructed Rome’s messengers to say that, although their community was at that point tiny and poor, the gods had granted it a brilliant future and that its more prosperous neighbors, instead of looking down on their impoverished neighbor, should recognize the Romans’ wondrous destiny and therefore make an alliance for their mutual benefit.

Every neighboring community refused Romulus’s request for marriage alliances. Desperate for a solution, the Roman king came up with a risky plan to kidnap the women he knew his community needed if it was to have a future. He invited the neighboring Sabine people to a religious festival at Rome. At a prearranged moment, Rome’s men dragged away the unmarried Sabine women. Unprepared for this assault, the Sabine men had to retreat home. The Roman men immediately married the kidnapped women, making them citizens. When a massive Sabine counterattack on Rome led to a bloody battle in which many Roman and Sabine men were being injured and killed, the Sabine brides suddenly rushed between the warring bands, shocking them into stopping the fight. The women then begged their new Roman husbands and their Sabine parents and brothers either to stop slaughtering each other and make peace, or kill them on the spot, their wives and daughters and sisters. Shamed by the women’s plea, the men not only made peace but also merged their two populations into an expanded Roman state. The role of women in this legendary incident both explained how immigration and assimilation of others were a foundation of Rome’s power and underlined the traditional Roman ideal of women as the mothers of Roman citizens, ready to sacrifice themselves for the survival of the community.

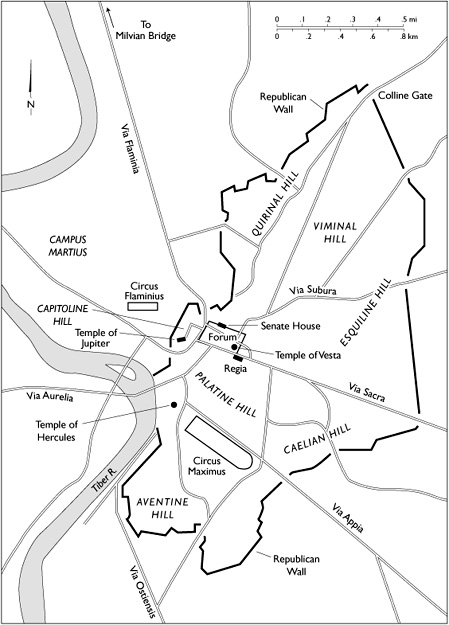

We do not have to decide how accurate this dramatic story is to see that it expressed the basic truth that early Roman history was a story of successful expansion and inclusion of others, through both war and negotiation. Moving out from their original settlement of a few thatched-roof huts on the hills of Rome, the Roman population grew over the next two centuries to such an extent that it occupied some three hundred square miles of Latium, enough agricultural land to support thirty to forty thousand people. Perhaps contracting with specialized Etruscan engineers to do the design work, the Romans in the mid-sixth century B.C. drained the formerly marshy open section at the foot of the Palatine Hill and Capitoline Hill to be the public center of their emerging city. Called the Roman Forum, this newly created central space remained the most historic and symbolic section in Rome for a thousand years. The creation of the Forum as a gathering place for political, legal, and business affairs, as well as public funerals and festivals, happened at about the same time that the Athenians in Greece created the agora to serve as the open, public center of their growing city. These roughly simultaneous rearrangements of urban space in Rome and Athens reveal the common cultural developments taking place around the Mediterranean region in this period. Over time, the Romans erected large buildings in and around the Forum to serve as meeting spaces for political gatherings, speeches, trials, and administrative functions of the government. Today the Forum presents a crowded array of ruins from centuries of Roman history. Walking through the Forum literally puts visitors into the footprints of the ancients, and standing there to read aloud a speech of Cicero, Rome’s greatest orator, or a poem of Juvenal, Rome’s most sharp-tongued satirist, can stir a visitor’s historical imagination to behold the ghosts of Rome’s glory and violence with a vividness attainable nowhere else on earth.

Map 2. The City of Rome During the Republic

Romans remembered and valued most of the seven kings as famous founders of lasting traditions. They credited the second king Numa Pompilius (ruled 715 B.C.–673 B.C.), for example, with establishing the public religious rituals and priesthoods that worshiped the gods to ask for their support for Rome. Servius Tullius (ruled 578 B.C.–535 B.C.) was believed to have created basic institutions for organizing Rome’s citizens into groups for political and military purposes, as well as the practice of giving citizenship to freed slaves. In the end, however, the monarchy failed as a result of opposition from the city’s upper class. These rich families thought of themselves as the king’s social equals and therefore resented the monarch’s greater power and status. They also resented the ordinary people’s support for the monarchy. The kings, in turn, feared that a powerful member of the upper class might use violence to take the throne for himself. To secure allies against such rivals, the kings cultivated support from citizens possessing enough wealth to furnish their own weapons but not enough money or social standing to count as members of the upper class. Around 509 B.C., some upper-class Romans deposed King Tarquin the Proud, an Etruscan who had become king, legend says, after Servius’s daughter Tullia forced Tarquin to murder her husband. She had made Tarquin marry her, and then kill Servius to become king of Rome himself. Tarquin the Proud lost his throne as a consequence of the unbending will of another, very different Roman woman, Lucretia. Tarquin’s son raped this virtuous upper-class wife at knifepoint. Even though her husband and father begged her not to blame herself for another’s crime, Lucretia committed suicide after identifying her rapist and calling on her male relatives to avenge her. She became famous as the ideal Roman woman: chaste, courageous, and ready to die rather than run the risk of even a suspicion of immoral behavior (Livy, From the Foundation of the City 1.57–60).

Led by Lucius Junius Brutus and calling themselves liberators, an alliance of upper-class men drove Tarquin from power and abolished the monarchy. They then established the Roman Republic, justifying their revolution with the argument that government dominated by one man inevitably led to abuses of power such as the rape of Lucretia. A sole ruler amounted to tyranny, they proclaimed. As mentioned at the beginning, the term “Republic” comes from the Latin phrase res publica (“the people’s thing, people’s business”; “commonwealth”). This name expressed the ideal of Roman government being of and for the entire community, with the people’s consent and in their interest (Cicero, The Republic 1.39). This ideal never became a full reality: the upper class dominated Roman government and society under the Republic.

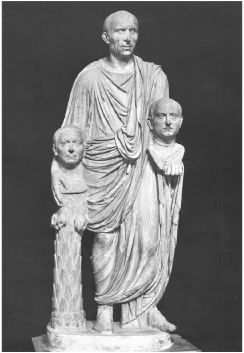

Figure 7. A statue of an upper-class Roman man shows him wearing formal clothing—a toga—and holding sculpted portraits of his ancestors. Standards of proper conduct called for Romans to demonstrate their respect for the “elders” of their family, living and dead. Alinari/Art Resource, NY

The upper class’s hatred of monarchy remained a central feature of Roman history for hundreds of years, a tradition enshrined in the legend of Horatius (Livy, From the Foundation of the City 2.10). Along with two fellow soldiers, he held off an Etruscan attack on Rome aimed at reimposing a king on the Romans, not long after the expulsion of Tarquin the Proud. Horatius blocked the enemy’s entry into Rome by driving their soldiers from a bridge over the Tiber River until his fellow Romans could destroy it, thereby blocking the foreign invasion. As the bridge collapsed into the water below, Horatius shouted out his mockery of the Etruscans as slaves who had lost their freedom because they were ruled by arrogant kings. He then jumped into the river still wearing his full metal armor and swam to safety and liberty. For the rest of their history, Romans of all social classes treasured the political liberty of their state that these legends described, but elite and ordinary citizens continued to disagree, sometimes violently, over how to share power in the government of the Republic that emerged from the struggles of their early history.

Romans, like other ancient peoples, believed that social inequality was a fact of nature. Consequently, they divided citizens by law into two groups called “orders,” one with much higher social status—the patrician order—than the other—the plebeian order. This division lasted throughout Roman history. The patricians were Rome’s original aristocrats, having inherited their status by being born in one of a tiny percentage of families—around 130 in total—ranked as patrician; no others could achieve this status. It is unknown how families originally gained patrician status, but it probably happened in a gradual process at the beginning of Rome’s history in which the richest Romans designated themselves as an exclusive group with special privileges to conduct religious ceremonies for the safety and prosperity of the community. Eventually, patricians leveraged their originally self-created elite status into almost a monopoly on the secular and religious offices of the early government of the Republic. Patricians proudly advertised their superior status. In the early Republic, they wore red shoes to set themselves apart. Later, they changed to the black shoes worn by all senators but adorned them with small metal crescents to mark their own particular prestige.

Because they possessed both high birth and great property, patrician men became Rome’s first social and political leaders, often controlling large bands of followers that they could command in battle. An inscription (the Lapis Satricanus) from about 500 B.C., for instance, says that “the comrades of Publius Valerius” erected a monument to honor Mars, the Roman war god. Valerius was a patrician, and it is significant that, when making this dedication to a national divinity, these men designated themselves as his supporters, instead of referring to themselves as citizens of Rome. There is also the famous story of the patriotism of the Fabius family. These patricians had so many followers that, when the state had already committed its regular forces to war on other fronts and therefore could not raise any more troops to fight against the neighboring Etruscan town of Veii in 479 B.C., the Fabians could raise a private army by assembling 306 men from their own family and a crowd of clients to wage the war on Rome’s behalf (Livy, From the Foundation of the City 2.48–49). That they were all wiped out by the army of Veii only makes the Fabians’ influence over their followers all the more impressive.

Map 3. Rome and Central Italy, Fifth Century B.C.

Plebeians made up all the rest of the population. They therefore greatly outnumbered the patricians. Many plebeians were of course poor, as was the majority of the population in all ancient civilizations. Some plebeians, however, were rich property owners and held important roles in public life. It would therefore be a mistake to see the plebeians only as “Rome’s poor and disrespected.” In fact, the wealthiest plebeians felt that they should have just as much influence in Roman society and politics as patricians. The poorest plebeians, on the other hand, were necessarily concerned with mere survival in a world with no social safety net. The plebeians were therefore a highly diverse group of citizens, whose interests did not necessarily coincide, depending on their relative wealth and position in society.

Conflict between members of the patrician order and well-off members of the plebeian order filled the two centuries following the creation of the Republic, deeply influencing the ultimate structure of the “Roman constitution.” For this reason, historians have usually referred to this period of turmoil in the fifth and fourth centuries B.C. as the Struggle of the Orders. This label implies that the trouble originated from plebeians demanding entry to the same high-level political and religious offices that the patricians had made into a near monopoly for themselves. Certainly, there was tension over the restrictive policies that the patricians imposed to wall themselves off socially from plebeians. Most strikingly, the patricians in the middle of the fourth century carried their exclusionary social policy to the limit: they banned intermarriage between themselves and plebeians. Recent research, however, shows that analyzing the unrest at Rome in this period as being only about political leadership and social status places too much emphasis on the struggle for political office, a mistake retrojected onto early Roman history by Livy and other historians of the first century B.C. By that time, the streets of Rome had been awash in bloodshed for decades from conflicts between plebeian and patrician leaders over access to privileged positions in the Roman state. It was therefore tempting to interpret the stories of unrest from early Roman history as previews of the conflicts of the time of the end of the Republic.

The sources of conflict between patricians and plebeians in the early Republic were as much economic as political. While well-off plebeians did want patricians to share with them access to the highest political offices and the social status that these positions brought, poor plebeians were the people most desperate for relief from the policies of the patricians in this period. In other words, the class conflict of the Struggle of the Orders was, for the majority of people, all about their literal survival because the poor, with their numbers increasing as Rome’s population grew, needed more land to farm to feed their families. Rich patricians, however, dominated the ownership of land and were also the source of loans to the poor.

The shortage of land to farm and the high interest rates charged on debts eventually led large numbers of plebeians to resort to drastic measures to try to protect their interests. In the bitterest disputes, they even physically withdrew outside the sacred boundary of the city to a temporary settlement on a neighboring hill. The plebeian men then refused to serve in the citizen-militia army. This “secession,” as it is called, worked because it devastated the national defense of the city, which had no professional standing army at this date. Instead, in times of war Rome’s male citizens gathered in the open, grassy area near the Tiber River called the Campus Martius (the field dedicated to Mars) for military training and exercise. At other times, they stayed at home to farm and support their families. When plebeian male citizens refused to take part in training for war or to show up when called from their homes and fields to defend the city in battle, then Rome was in grave danger because the patricians were far too few to protect Rome by themselves. The need to have plebeians serve in the national defense force was the fundamental reason why the patricians ultimately had to compromise with them, even though the elite hated yielding to the demands of those whom they considered their social inferiors.

Roman tradition says that the compromise between patricians and plebeians led to Rome’s first written laws. The new legal code was put in place following the mission of a Roman delegation to Athens, where they studied how that famous Greek city had created a written law code. Even with this research, it took a long time for the two Roman orders to reach final agreement on laws to protect the plebeians, while also maintaining the status of the patrician order. The earliest written code of Roman law, called the Twelve Tables, was enacted between 451 and 449 B.C. As a compromise between two powerful groups, it was inevitably less than a clear-cut victory for plebeian interests. In fact, patricians took advantage of this occasion to impose the infamous ban on intermarriage with plebeians. Importantly for plebeians, however, having a written code of laws prevented the patrician magistrates who judged most legal cases from arbitrarily and unjustly deciding disputes merely according to their own personal interests or those of their order. At the very least, the existence of the Twelve Tables as written and therefore publicly accessible laws made it harder for a magistrate to make up a law on the spot to use against a plebeian. The concise provisions of the Twelve Tables encapsulated the prevailing legal customs of the agricultural society of early Rome with simply worded laws such as, “If plaintiff calls defendant to court, he shall go,” or “If a wind causes a tree from a neighbor’s farm to be bent and lean over your farm, action may be taken to have that tree removed” (Warming-ton vol. 3, pp. 424–515).

In later times the Twelve Tables became a national symbol of the Roman commitment to legal justice. Children were still being required to memorize these ancient laws four hundred years later. Emphasizing legal matters such as disputes over property, the Twelve Tables demonstrated the overriding Roman interest in civil law. Roman criminal law, on the other hand, never became extensive. Courts therefore never had a full set of rules to guide their verdicts in all cases. Magistrates decided most cases without any juries. Trials before juries began to be common only in the late Republic of the second and first centuries B.C. Nevertheless, the Twelve Tables marked a beginning, if a flawed one, in establishing written law as a source of justice to reduce violent class conflict in Roman society.

The “Roman constitution” included a range of elected officials and one special body, the Senate. Only the most ambitious and most successful of Roman men could hope to win election as the highest officials in the government of the Republic, the consuls. The Republic had been created to prevent Rome from being ruled by a single leader inheriting his position and governing by himself for an indefinite term. The office of consul was therefore created so that each year two leaders of the state would be elected to serve together, with a single-year term limit and a ban on reelection to consecutive terms. They received the name “consuls,” meaning something like “those who take care [of the community],” to make the point that these officials, despite the great status they derived from their positions, were supposed to act in the interests of all Romans, not just themselves or their supporters. The consuls’ duties were to provide leadership on civil and political policy and command the army in times of war. The competition to reach this office was intense not only because it gave a man enormous individual status but also because it elevated his family’s prestige forever. Families with even a single consul among their ancestors called themselves “the nobles.” Upper-class Roman men without a consul in their family history strongly wanted to win election as a consul, to elevate themselves and their descendants into this self-identified status group.

The Senate was the most prestigious institution of the “Roman constitution” and lasted throughout all the centuries of Roman history. Its origins lay in the time of the Monarchy because the kings of Rome did not make important decisions by themselves, in accordance with the Roman tradition of always asking for advice from one’s friends and elders. The kings therefore had assembled a select group of elite men to be their royal council; these senior advisers were called senators (from the Latin word for “old men”). The tradition that the leaders of Roman government should always seek advice from the Senate continued under the Republic even after the expulsion of the monarchy. For most of the Senate’s history, it had 300 members. The general and politician Sulla increased the membership to 600 as part of his violent reforms of Roman government in 81 B.C., Julius Caesar raised it to 900 to gain supporters during the civil war of the 40s B.C., and finally Augustus brought it back to 600 by 13 B.C. So far as we can tell, the Senate had always included both patricians and elite plebeians. Eventually, men had to own a set (and high) amount of property to be eligible to serve as senators.

During the Republic, senators were at first selected by the consuls from the pool of men who had previously been elected as lesser magistrates. Later, the choice was made from that same population pool by two special magistrates of high prestige called censors. In time, the Senate achieved a tremendous influence over Republican domestic and foreign policy, state finances, official religion, and all types of legislation. Senatorial influence was especially prominent in decisions about declaring and conducting wars. Because Rome in this period fought wars almost continually, this function of the Senate was critically important. The Senate endured as a high-prestige institution throughout Roman history, even under the emperors, when the political influence that it had possessed in the government of the Republic was reduced to cooperating with the emperor as a much inferior partner in governing. The Senate House that today stands in the Roman Forum was built in the late Empire, showing that the position of senator still enjoyed great status even more than a thousand years after the foundation of Rome.

The basis of the Senate’s power provides one of the most revealing clues to the nature of Roman society, in which social status brought influence and authority that could equal or even exceed the power of statute law. The power of the Senate legally consisted only in the right to give advice to the leading officers of the state, by voting to express its approval or disapproval of policies or courses of action. It did not have the right to pass laws. Moreover, the Senate had no official power to force officials to carry out its wishes. In other words, the senators’ ability to affect, even to direct, Roman law and society came not from any official right to impose policy or legislation, but solely from their status as Rome’s most respected male citizens. Therefore, the Senate’s power depended entirely on the influence over officials and citizens that it derived from the social importance of its members. To understand the inner workings of Roman society and politics, it is necessary to recognize that it was simply the high status that senators enjoyed that endowed their opinions with the force—although not the form—of law. For this reason, no government official could afford to ignore the advice of the Senate. Any official who defied its wishes knew that he would likely face serious opposition from many of his peers. The extraordinary status of the senators was made visible for all to see, as usual in Roman society. To broadcast their identity, Senators wore black, high-top shoes and a broad purple stripe embroidered on the outer edge of their togas.

The Senate used an apparently democratic procedure, majority vote of its members, to decide what advice to offer the officials of government. In reality, however, considerations of relative status among the senators themselves had a major impact on decisions. The most distinguished senator had the right to express his opinion first when a vote was taken. The other senators then spoke and voted in descending order of prestige. The opinions of the most distinguished, usually older senators carried by far the most weight. Only foolish junior senators with no eye on their political futures would dare give an opinion or cast a vote different from those already expressed by their elders.

As in ancient Greece, at Rome the only honorable and desirable career for a man of high social standing was holding public office, or, as we might label it, a career in government. The office of consul, of course, was the most prestigious of the annually elective public offices under the Roman Republic. The other elective civil offices were ranked in order of prestige below consul in what is often called the “ladder (or course) of offices” (cursus honorum). There were also elective priesthoods laddered according to the status that they brought to their holders. At the beginning of the Republic, the patricians dominated election to the highest positions in the ladders of offices, especially that of consul, even passing laws that restricted a certain number of these coveted posts to members of their own order.

An ambitious Roman man with the resources to win over voters with financial favors and entertainments would climb this ladder of success by winning election to one post after another in ascending order. He would begin his career at perhaps twenty years old by serving on military campaigns for as much as ten years, usually as an assistant officer appointed to the staff of an older relative or friend. He would next begin his climb up the ladder of offices by seeking election to the lowest of the important annual positions, that of quaestor. Candidates to be elected quaestor would usually be in their late twenties or early thirties. During their year in office, quaestors performed a variety of duties in financial administration, usually concerning the oversight of state revenues and payments, whether for the treasury in the capital, for commanders on campaign, or for the governing staffs of the overseas provinces that Rome established beginning in the third century B.C. Eventually, minimum age requirements for the various positions in the ladder of offices were set by law. After Sulla in 81 B.C. prescribed strict regulations for progress up the ladder, a man who had served as a quaestor was automatically eligible to be chosen as a senator when a place in that body opened up. After quaestor, the next rung up the ladder was the office of aedile. Aediles had the difficult duty of maintaining Rome’s streets, sewers, temples, markets, and other public works.

Figure 8. This diagram plots the highly competitive career path—the ladder of offices—in government and politics that upper-class Roman men aimed to climb. The competition became more heated the higher a man climbed, and comparatively few made it to the small number of offices at the top. Diagram created by Barbara F. McManus, used courtesy of the VRoma Project, www.vroma.org.

The next step up the hierarchy of offices was to win election to the annual office of praetor, a prestigious magistracy second only to being a consul. Praetors had a variety of civil and military duties, including the administration of justice and commanding troops in war. Since there were fewer praetors elected than quaestors (the number of both changed over time), competition for this high office was fierce.

The great prestige of praetors sprang primarily from their role as commanders of military forces, because success as military leader earned a man the highest status in Roman society. Only those who succeeded as praetors and had strong support from a broad section of the voting population could hope to become consuls. Consuls were supposed to be older men with long experience in politics; according to the regulations established by Sulla in the early first century B.C., candidates for election as consuls had to be at least forty-two years old. The two consuls had influence on every important matter of state and commanded the most important detachments of the Roman army in the field. Like praetors, consuls could have their military command extended beyond their one-year terms of office if they were needed as commanders abroad or as the governors of provinces (on which see p. 73). When serving on these special tours of duty outside Rome after their year in office, they were designated propraetors and proconsuls. These “promagistrates,” as they are called, had great power in the regions to which the Senate assigned them, and there was strong competition among Roman leaders to get the best assignments. Promagistrates lost their special power to command or to govern after they returned to Rome.

Consuls and praetors could exercise military command because by law their offices gave them a special power called imperium (the root of the word “empire”). Imperium guaranteed an official the right to demand obedience from Roman citizens to any and all of his orders. It also carried the authority to perform the crucial religious rites of divination called auspices (auspicia). Roman tradition required officials with this power to take the auspices to discern the will of the gods before conducting significant public events, such as elections, inaugurations into offices, officials’ entrance into provinces, and, especially, military operations. The power and the prestige of these positions made them the center of the dispute between patricians and plebeians over political offices. The conflict over these valued capstones to a man’s career finally came to an end in 337 B.C., when pressure from the plebeians forced the passage of a law that opened all offices equally to both orders.

The “Roman constitution” also included two special, nonannual posts that were not part of the regular ladder of offices. These were the offices of censor and dictator. Every five years, two censors were elected to serve for eighteen months. They had to be ex-consuls, elder statesmen believed to possess the exceptional prestige and wisdom necessary to carry out the office’s most crucial duty: conducting a census listing all male Roman citizens and the amount of their property, so that taxes could be levied fairly and male citizens could be classified for military service in war. The censors also controlled the membership of the Senate, filling any empty seats with worthy candidates and removing from its rolls any man they decided had behaved improperly. Censors also supervised state contracts and oversaw the renewal of official prayers for the goodwill of the gods toward the Roman People.

The office of dictator was the only kind of one-man rule allowed under the “Roman constitution.” It was filled only in dire national emergencies when quick decisions needed to be made to save the state. This usually meant that Rome had suffered a military catastrophe and needed swift action to prevent further disaster. The Senate chose the dictator, who had absolute power to make decisions that could not be questioned. This extraordinary office was meant to be strictly temporary, and dictators were allowed to stay in office for a maximum of six months. The most famous dictator under the Republic was Cincinnatus, who because of his selfless conduct in this office in 458 B.C.—he refused to remain in office even though many wanted him to continue as sole ruler—summed up the Roman ideal of community-minded public service being more important than individual success.

It is important to stress how much the holding of an elective position or a special office in Roman government meant to patricians and upper-class plebeians from the status that such posts brought them. Since status by definition was meaningless unless others recognized it, the prestige attached to top-ranking offices was expressed in highly visible ways. Each consul, for example, was preceded wherever he went by twelve attendants. These attendants, called lictors, carried the fasces. The fasces were the symbol of the consul’s imperium. Inside the city limits, the fasces consisted of a bundle of sticks to symbolize the consul’s right to beat citizens who disobeyed his orders; outside the city, an axe was added to the sticks to symbolize his right to execute disobedient soldiers in the field without a trial. Lictors also accompanied praetors because they, too, were magistrates with imperium, but praetors had only six lictors apiece to show that their status was less than that of the consuls.

Figure 9. The Via Appia was the main route from Rome to south Italy, named after Appius Claudius Caecus, the upper-class man who paid for its first 132 miles of paving. These hard-surfaced highways allowed travel in all weather, making the deployment of military forces and the transportation of passengers and goods more reliable. MM/Wikimedia Commons.

The value of a public career had nothing to do with earning a salary, which Roman officials did not receive, or with gaining money by exploiting the power of one’s official position, at least not in the earlier centuries of the Republic. On the contrary, officials were expected to spend their own money on their careers and public service. Therefore, the only men who could afford to serve in government were those with income from family property or friends who would support them financially. The expenses required to win an electoral campaign and secure a reputation for community-minded service in office could be crushing. To win the support of voters, candidates often had to go deeply into debt to finance hugely expensive public festivals featuring fights among gladiators and staged killings of exotic wild animals imported from Africa. Once he was elected, an official was expected to pay personally for public works such as roads, aqueducts, and temples that benefited the whole populace. In this way, successful candidates were expected to serve the common good by spending their own money—or money they borrowed from their friends and clients.

Roman officials originally found personal rewards for their service only in the status that their positions brought while in office and in the high esteem that they could enjoy afterwards if they were seen as having been morally upright and generous public servants. But as the Romans later in the Republic came to dominate more and more overseas territory won as the spoils of war, the opportunity to make money from conquering and governing foreigners became an increasingly important component of a man’s successful public career. Officials could legally enrich themselves by winning booty while serving as commanders in successful wars of conquest against foreigners. Corrupt officials could also profit by taking gifts and bribes from local people while administering the provinces created from Rome’s conquered territories. In this way, Rome’s former enemies financed their conquerors’ public careers and private riches.

Romans voted in assemblies to decide elections, set national policy, and pass laws. The complexity of the Republic’s voting assemblies almost defies description. Rome’s free, adult male citizens met regularly in these open-air gatherings to vote on legislation, hold certain trials, and elect officials. Roman tradition specified that an assembly had to be summoned by an official, held only on days seen as proper under religious law, and sanctioned by favorable auspices. Assemblies were for voting, not for discussing candidates for office or possible policies for the government to adopt. Discussion and debate took place before the assemblies, in a large public meeting that anyone, including women and noncitizens, could attend but at which only male citizens could speak. Since a presiding official decided which men could speak, he could control the course of the debate, but nevertheless there was a considerable opportunity for expressing different opinions and proposals. Everyone listening to the speakers could express their views at least indirectly by cheering or booing what was said. An unpopular proposal could expect to be greeted with loud jeers and shouts of ridicule at these meetings. Once the assembly itself began, votes could be taken only on matters proposed by the officials, and amendments to the official proposals were not permitted at that point.

Rome had three main voting assemblies: the Centuriate Assembly, the Tribal Assembly of the Plebeians, and the Tribal Assembly of the People. It is crucial to recognize that there was no “one man, one vote” rule. Instead, the men in the assemblies were divided into a large number of groups according to specific rules that were different for each type of assembly. The groups were not equal in size. The members of each group would first cast their individual votes to determine what the single vote of their group would be in the assembly. Each group’s single vote, regardless of the number of members of that group, then counted the same in determining the decision of the assembly by majority vote of the groups.

This procedure of voting by groups placed severe limits on the apparent democracy of the assemblies. The Centuriate Assembly offers us the clearest example of the effects of the Roman principle of group voting. This important assembly elected censors, consuls, and praetors; enacted laws; declared war and peace; and could inflict the death penalty in trials. The groups in this assembly, called centuries (hence the assembly’s name), were organized to correspond to the divisions of the male citizens when they were drawn up as an army. Since early Rome relied not on a standing army financed by taxes but on a citizen militia, every citizen had to arm himself at his own expense as best he could. The richer he was, the more a man contributed by spending more on his weapons and armor. This principle of national defense through individual contributions meant that the richer citizens had more and better military equipment than did the poorer, much more numerous citizens.

Consequently, the rich were seen as deserving more power in the assembly to correspond to their greater personal expenses in military service defending the community. In line with this principle, the cavalrymen, who had the highest military expenses because they had to maintain a warhorse year round, made up the first eighteen groups of the total of 193 voting groups in the Centuriate Assembly. The next 170 groups in this assembly consisted of foot soldiers ranked according to how much property they owned, from highest to lowest. The next four groups consisted of noncombatants providing services to the army, including carpenters and musicians. The final group, the proletarians, was made up of those who were too poor to afford military weapons and armor and therefore did not serve in the army. All they contributed to the state were their children (their proles, hence the term proletarian).

The grouping of voters in the Centuriate Assembly therefore corresponded to the distribution of wealth in Roman society. Far more men belonged to the groups at the bottom of the social hierarchy than to those at the top, and the proletarians formed the most numerous group of all. But these larger groups still had only one vote each. Moreover, the groups voted in order from richest to poorest. As a result, the rich could vote as a bloc in the assembly and reach a majority of the group votes well before the voting even reached the groups of the poor. When the elite groups voted the same way, then, the Centuriate Assembly could make a decision in an election or on legislation without the wishes of the lower classes ever being expressed at all through their votes.

The voting groups in the Tribal Assembly of the Plebeians were determined on a geographical basis, according to where the voters lived. The assembly got its name from the Roman institution of tribes, which were not kinship associations or ethnic groups but rather a set of area subdivisions of the population for administrative purposes. By the later Republic, the number of tribes had been fixed at thirty-five, four in regions of the capital city and thirty-one in the Italian countryside. The tribes were structured geographically so as to give an advantage to wealthy landowners from the countryside. This Tribal Assembly excluded patricians. Consisting therefore only of plebeian voters, it conducted nearly every form of public business imaginable, including holding trials.

In the first centuries of the Republic, the proposals passed by the plebeians in this assembly, called plebiscites, were regarded only as recommendations, not laws, and the aristocrats who dominated Roman government at the time often ignored the plebiscites. Plebeians became angrier and angrier at the elite’s arrogant disregard for their wishes as the majority of the population. By repeatedly employing their tactic of secession from the state, the plebeians eventually forced the patricians to give in. The plebeians’ final withdrawal in 287 B.C. led to an official agreement to make plebiscites the source of official laws. This reform transformed the results of votes taken in the Tribal Assembly of the Plebeians from mere recommendations into a principal source of legislation binding on all Roman citizens, including patricians. The recognition of plebiscites as official law finally ended the Struggle of the Orders between plebeians and patricians because it formalized the electoral, legislative, and judicial power of the majority of the population.

The Tribal Assembly of the Plebeians elected the plebeian aediles and, most importantly, the ten tribunes, special and powerful officials devoted to protecting the interests of the plebeians. As plebeians themselves, tribunes derived their power not from official statutes or rules but rather from the sworn oath of the plebeians to protect them against all attacks. This sacred inviolability of the tribunes, called sacrosanctity, allowed them to exercise the right of veto (a Latin word meaning “I forbid”) to block the action of any official, even a consul, and to prevent the passage of laws, to suspend elections, and to reject the advice of the Senate. Tribunes’ power to obstruct the actions of officials and assemblies gave them an extraordinary potential to influence Roman government. Tribunes who exercised their full powers in controversial situations could become the catalysts for bitter political disputes, and the office of tribune itself became one hated by many of the most elite Romans, who resented its ability to obstruct their wishes.

In a later development, the Tribal Assembly also met in an expanded form that included patricians as well as plebeians. When meeting in this form, it became Rome’s third type of political assembly. Called the Tribal Assembly of the People, it elected the quaestors; the two curule aediles (whose higher status was indicated by their special portable chairs, the sella curulis also used by consuls and praetors; originally, only patricians could hold these positions); and the six senior officers (military tribunes) of the largest units in the army. The Tribal Assembly of the People also enacted laws and held minor trials.

In sum, then, the “Roman constitution” included a network of government offices and voting assemblies whose powers often overlapped and conflicted. Very little was clear or unambiguous about the distribution of power in the government of the Republic, which opened the door to frequent political conflicts. Perhaps the most serious source of conflict was the fact that multiple political institutions could make laws or their equivalent (meaning the advice given by the Senate), but Rome had no central authority or judicial body, such as the United States Supreme Court, to resolve disputes about the validity of overlapping or conflicting laws. Rather than depend on institutions of government with clearly defined and limited competencies, the Romans entrusted the political health and stability of their Republic to a generalized respect for tradition, the famous “way of the elders.” This characteristic in turn ensured that the socially most prominent and richest Romans dominated government because their status enabled them to control what that “way” should be in the context of politics.