The violent conflict that turned Rome’s ruling elite against itself eventually destroyed the Republic. The process of destruction took a century, from the time of the Gracchus brothers’ terms as tribunes to the civil wars of the second half of the first century B.C. The process was also an outgrowth of a perversion of the ancient Roman tradition of the mutual obligations of patrons and clients. This corruption of the “way of the elders” began in the late second century B.C., when the Roman state faced dangerous new threats that demanded immediate military responses under competent commanders. For one, seventy thousand slaves escaped from large estates in Sicily and banded together to launch a revolt that lasted from 134 to 131 B.C. In 112 B.C., an overseas war broke out with Jugurtha, a rebellious client king in North Africa. Another threat closer to home arose soon thereafter, when bands of invading Gallic warriors launched raid after raid in the northern regions of Italy.

The intensity of these dangers gave an opening for the emergence of a new kind of leader—the man not born into the privileged circle of the highest nobility at Rome, but who had the abilities and military skill to propel him to election as a consul and the great status and influence that this office brought with it. Men who became consuls despite lacking a distinguished family history were called “new men.” To gain the support that they needed to overcome the social prejudice against them, as military commanders these “new men” were especially generous to their soldiers in distributing booty and looking after their needs. Ordinary Roman soldiers, many of whom were poor, became more and more willing to follow such a commander as their patron, operating as his clients and more obedient to him personally than to the Senate or Assemblies. In this way, the patron-client system became more a way for leaders to gain great individual power than a support for the interests of the community as a whole.

107: Marius becomes a “new man” by winning election as consul; he is reelected for a total of six consecutive terms.

91–87: The Romans and their allies in Italy fight each other in the Social War.

88: Sulla commands his Roman army to capture Rome.

88–85: The Romans fight the First Mithradatic War against King Mithradates VI of Pontus in Asia Minor.

63: Pompey captures Jerusalem; Catiline attempts to seize control of Roman government in a violent conspiracy.

60: Pompey, Crassus, and Julius Caesar form the First Triumvirate to dominate Roman government.

59: Julia, daughter of Julius Caesar, marries Pompey in a political alliance between the two rival leaders.

58–50: Julius Caesar fights the Gallic War to conquer Gaul (today France).

53: Political violence in Rome’s streets prevents the election of consuls for the year.

50s: Lucretius composes his epic poem On the Nature of Things, which explains atomic theory to dispel the fear of death.

49: Julius Caesar crosses the Rubicon River into Italy, and civil war begins.

45: Julius Caesar has defeated all his opponents in the Civil War and gained control of Rome; in his will he adopts Octavian (the future Augustus).

44: Julius Caesar declares himself “Dictator Always” and is murdered on the Ides of March.

This undermining of Roman tradition came at a time of national crises, with wars to fight both against Rome’s Italian allies and the charismatic and clever King Mithradates in Asia Minor. A crushing blow to the stability of the Republic came with the commander Sulla’s violent demonstration of his contempt for the ancient Roman value of placing one’s loyalty to the community above one’s own desire for power and glory. The ideal that the poet Lucilius had long ago expressed—put your own interests last, after your country’s and your family’s—had lost its power to inspire Rome’s most ambitious leaders.

“New men” departed from the traditional Roman path to leadership, by which men from famous old families expected to inherit their positions at the top of society and politics. The man who more than anyone else put this new political force into motion was Gaius Marius (157 B.C.–86B.C.). From a family of the equestrian order in the town of Arpinum in central Italy, in the earlier Republic Marius would have had little chance of cracking the ranks of Rome’s elite leadership, which had almost monopolized the office of consul. The best that a man of Marius’s origins could usually hope for in a public career was to advance to the junior ranks of the Senate, as the dutiful client of a powerful noble. Fortunately for Marius, however, Rome at the end of the second century B.C. had a pressing need for men with his ability to lead an army to victory. Marius made his reputation by serving with great distinction in the North African war. He first made his way up the political ladder of elective offices by supporting the interests of noble patrons, and he also helped his career by marrying above his social rank into a famous patrician family. Finally, capitalizing both on his outstanding military record and also on the ordinary people’s dissatisfaction with the nobles’ conduct of the war against Jugurtha, Marius stunned the upper class by winning election as one of the consuls for 107 B.C., thereby becoming a “new man.” Marius reached this pinnacle because his exceptional accomplishments as a general came at a time when Rome desperately needed military success. The African war had dragged on through the incompetence of its generals until Marius took over, but the most significant reason for Marius’s reputation and popularity with the voters were his victories over the Celtic peoples from the north called Teutones and Cimbri, who repeatedly tried to invade Italy in the last years of the second century B.C. Remembering with horror the sack of Rome by other northern “barbarians” in 387 B.C., Rome’s voters by 100 B.C. had elected Marius as consul for an unprecedented six terms. His tenure in Rome’s highest office included service in consecutive terms, a practice previously considered “unconstitutional.”

So famous was Marius that the Senate voted him a triumph, Rome’s ultimate military honor, a rare recognition granted only to generals who had won stupendous victories. On the day of a triumph, the general rode through the streets of Rome in a military chariot. His face (or perhaps his entire body) was painted red for reasons that the Romans could no longer remember. Huge crowds cheered him on. His army traditionally shouted off-color jokes about him, perhaps to ward off the evil eye or remind him not to be overcome by a more than human pride at this moment of supreme glory. For the same reason, someone (perhaps a slave) stood behind him in the chariot and kept whispering in his ear a warning to avoid being corrupted by hubristic pride: “Look behind you, and remember that you are a mortal man” (Tertullian, Apology 33; Jerome, Letters 39.2.8). For someone with Marius’s relatively humble background to be granted a triumph was a social coup of mammoth proportions.

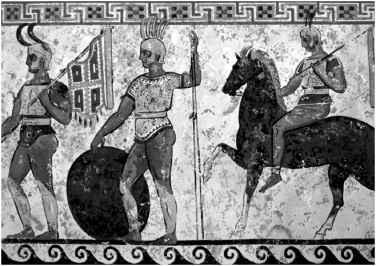

Figure 13. These Roman soldiers shown standing in a religious procession have armor of the type used in the Republic; rectangular shields later became more common. Soldiers had to train energetically to maintain the strength needed to wield their heavy weapons effectively in their ordered ranks in battle. Marie-Lan Nguyen/Wikimedia Commons.

Despite his triumph, Marius never achieved full acceptance by Rome’s highest social elite. They saw him as an upstart and a threat to their preeminence. Marius’s genuine support came from both wealthy equestrians and ordinary people. Equestrians probably supported his attempt to break into the nobility as a proof of the worth of men of their social class, but most of all they were concerned that the demonstrated incompetence of contemporary leaders from the senatorial class was having a disastrous effect on their economic interests abroad.

Marius’s reform of entrance requirements for the army was the key factor in his popularity with the poorer ranks of Roman society. Previously, only citizens who owned property could enroll as soldiers—and therefore hope to win the rewards of status and plunder that soldiers could gain in victorious military campaigns. Proletarians, who by definition had no property, had been barred from becoming soldiers. Marius, completing a process that others had started earlier, had this bar removed so that even proletarians could enroll in the army. For these people who owned virtually nothing, the opportunity to better their lot by acquiring booty under a successful general more than outweighed the risk of the danger of being injured or killed in war.

The Roman state at this time provided no regular compensation or pensions to ex-soldiers. Their livelihood depended entirely on the success and the generosity of their general. By this time, there was no more conquered land in Italy to distribute to veterans, and taking land from provincials outside Italy was generally avoided as a way to avoid provoking open hostility to Roman control. Therefore, ordinary troops depended on a share of the booty seized in battle if they were to benefit financially from war. Since, if the general wished, he was entitled to keep the lion’s share of booty for himself and his high-ranking officers, his common soldiers could end up with little. Impoverished as they were, proletarian troops naturally felt extraordinary gratitude to a commander who led them to victory and then made a generous division of the spoils with them. As a result, the legions’ loyalty came more and more to be directed at their commander, not to the state. In other words, poor Roman soldiers began to behave as an army of clients following their general as a personal patron, whose commands they obeyed regardless of what the Senate wanted.

The Roman army was most likely also reorganized to fight with new tactics and improved weapons at this time. Legions were now composed of ten units of 480 men each, called “cohorts.” Each cohort had six “centuries” of 80 men, commanded by a centurion. On the battlefield the soldiers faced the enemy in an arrangement of four cohorts in the front line, with two lines of three cohorts behind. Each cohort was separated by a gap from the others, and the two lines in the back were lined up in the gaps among the cohorts in the front line. This spacing gave the cohorts room for flexible movement in response to changing conditions during battle. For the first time, the Roman army was equipped with uniform weapons and equipment instead of whatever arms the individual soldiers brought with them. The main infantry carried heavy and light javelins, swords, and large oval—later rectangular—shields. Marius redesigned the heavy javelins so that they would bend after impact in an enemy’s shield, thereby impeding his movement and making him easier to kill. After throwing their javelins, Roman soldiers rushed the enemy to use their swords in close-in fighting.

Marius deserves credit for increasing the fighting effectiveness of the Roman army by improving both tactical cohesiveness and flexibility, but his reforms had unforeseen consequences. The kind of client army that he created became a source of political power for unscrupulous commanders that destabilized the Republic politically. Marius himself, however, was too traditional to use a client army to maintain his own career. He lost his political importance soon after 100 B.C. because he was no longer commanding armies and had alienated many supporters by deferring to the upper class. His enemies among the optimates capitalized on his missteps to block him from exercising further political influence. Nevertheless, Marius had established a precedent for a general to achieve supreme political power by treating the soldiers as personal clients. Other leaders later on would extend this precedent to its logical conclusion: the general ruling Rome by himself, not as a member of a shared government in the old tradition of the Republic.

Long-standing tensions between Rome and its Italian allies erupted into war in the early first century B.C. By Roman tradition, these allies shared in the rewards of military victory. Since they were not Roman citizens, however, they had no voice in decisions concerning Roman domestic or foreign policy. This political disability made them increasingly unhappy as wealth from conquest piled up in Italy in the late Republic. The allies wanted a bigger share in the growing prosperity of the upper classes. Gaius Gracchus had seen the wisdom for the state of extending Roman citizenship to its loyal allies in Italy (and would, of course, also have increased his own power when the grateful new citizens became his clients). His enemies, however, had defeated Gracchus’s proposal by convincing Roman voters that they would harm their own political and economic interests by granting citizenship to the Italian allies.

The allies’ discontent finally erupted into violence in the Social War of 91 B.C.–87 B.C. (so called because the Latin word for “ally” is socius). The Italians formed a confederacy to fight Rome, minting their own coins to finance their violent rebellion. One ancient source claims 300,000 Italians died in battle. The Romans won the war, but the allies prevailed in the end because, to secure the peace, the Romans granted the Italians the citizenship for which they had begun their revolt. From then on, the freeborn peoples of Italy south of the Po River enjoyed the privileges of Roman citizenship. Most importantly, if their men made their way to Rome, they could vote in the assemblies. The bloodshed of the Social War was the unfortunate price paid to reestablish Rome’s early principle of seeking strength by admitting outsiders to membership in its community.

Rome’s troubles as a ruler over others increased in this same period when provincials in Asia Minor rebelled. King Mithradates VI of Pontus was able to convince them to rebel above all because they so bitterly resented the notorious Roman tax collectors. The Roman state did not have officials to collect taxes. Instead, it subcontracted that task to private entrepreneurs through annual auctions. Whoever bid the largest amount for the revenue of a particular province received a contract to collect its taxes for that year. The contractor promised to deliver that amount to Rome and was then entitled to keep as profit whatever surplus could be squeezed out of the provincials. Groups of Romans from the equestrian class formed private companies to compete for these provincial tax contracts. The harder these tax collectors pressed the locals, the more money they made. And press they did. It is no wonder, then, that Mithradates found a sympathetic ear in Asia Minor for his charge that the Romans were “an affliction on the entire world” (Sallust, Histories 4 frag. 69). A superb organizer, he arranged for the rebels to launch a simultaneous surprise attack on Romans in many locations in Asia Minor on a preestablished date. They succeeded spectacularly, murdering tens of thousands in a single day. This crisis led to the First Mithradatic War (88 B.C.–85 B.C.), which Rome won only with great difficulty. It took two more wars before Mithradates’s threat to Roman domination in this part of the world was finally ended.

The Social War and the threat from Mithradates brought to power a ruthless Roman noble, Lucius Cornelius Sulla, whose career further undermined the stabilizing effect of Roman tradition in keeping the community together. Sulla came from a patrician family that had lost much of its status and wealth. Anxious to restore his line’s prestige and prosperity, Sulla first schemed to advance his career while serving under Marius against Jugurtha in North Africa. His military success against the allies in the Social War then propelled him to the prominence that he coveted: he won election as consul in 88 B.C. The Senate promptly rewarded him with the command against Mithradates in Asia Minor.

Marius, jealous of his former subordinate, plotted to have Sulla’s command transferred to himself. Sulla’s reaction to this setback showed that he understood the source of power that Marius had made possible by creating a client army. Instead of accepting the loss of the command, Sulla did the unthinkable: he marched his Roman army to attack Rome itself. All his officers except one, Lucullus, deserted him in horror at this treason. Sulla’s ordinary soldiers, by contrast, all obeyed him. Neither they nor their commander shrank from starting a civil war. Capturing Rome with his Roman citizen troops, Sulla brutally killed or exiled his opponents. His men went on a rampage in the capital city. He then led them off to campaign in Asia Minor, ignoring a summons to stand trial.

Figure 14. This painting depicts soldiers armed in the style of the Samnites, an Italian people famous for their valor in war. Distinctive armor was important to warriors not just for combat but also to demonstrate their status and honor. Wikimedia Commons.

After Sulla left Italy, Marius and his friends retook power in Rome and embarked on their own reign of terror. By employing violence to avenge violence, they bluntly demonstrated that Roman politics had become a literal war at home. Marius soon died, but his friends held undisputed power until 83 B.C., when Sulla returned to Italy after a successful campaign in Asia Minor. Another civil war followed when Sulla’s enemies joined some of the Italians, especially the Samnites from central and southern Italy, to resist him. The climactic battle of the war took place in late 82 B.C. at the Colline Gate of Rome. The Samnite general whipped his troops into a frenzy against Sulla by shouting, “The final day is at hand for the Romans! These wolves that have so ravaged the freedom of the Italian peoples will never vanish until we have cut down the forest that harbors them” (Velleius Paterculus, The Roman Histories 17.2).

Unfortunately for the Samnites, they lost this battle and the war. Sulla then proceeded to exterminate them and give their territory to his supporters. He also terrorized his opponents at Rome by using a martial law measure called “proscription.” This tactic meant posting a list of the names of people who were accused of treasonable crimes. Anyone could then hunt down and kill these people, with no trial necessary. The property of the “proscribed” was confiscated and distributed to the murderers. Sulla’s supporters therefore added to the list the names of perfectly innocent citizens whose wealth they simply wanted to seize, under the pretext that they were punishing traitors. Terrified by Sulla’s ruthlessness, the senators appointed him dictator, but without any limitation of term. This appointment was of course completely contrary to the Republic’s tradition of limiting this office to short-term national emergencies.

Sulla used his unprecedented dictatorship to legitimize his reorganization of Roman government. He claimed that he was returning the Republic to the heart of its tradition by giving control to the “best people.” He therefore made the Senate into the supreme power in the state. He also changed the composition of juries so that equestrians no longer judged senators. He severely weakened the office of plebeian tribune by prohibiting the tribunes from offering legislation without the prior approval of the Senate and barring any man who became a tribune from holding any other office thereafter. Minimum age limits were imposed for holding the various posts in the ladder of offices.

Convinced by an old prophecy that he had only a short time to live, Sulla retired to private life in 79 B.C. He in fact died the next year. His violent career had starkly revealed the changes in Roman social and political traditions by the time of the late Republic. First, success in war had come to mean profits for commanders and ordinary soldiers alike, primarily from selling prisoners of war into slavery and seizing booty. This profit incentive for waging war made it much harder to resolve problems peacefully. Many Romans were so poor that they preferred war to a life without prospects. Sulla’s troops in 88 B.C. did not want to disband when the governing elite ordered them to do so because they had their eyes on the riches they hoped to win in a war against Mithradates. Second, the extension of the patron-client system to the military meant that poor soldiers felt stronger ties of obligation to their general, who acted as their patron, than to their country. Sulla’s men obeyed his order to march on their own capital because they owed obedience to him as their patron and could expect benefits in return. Sulla benefited them by permitting the plundering of Rome and of the vast riches of Asia Minor.

Finally, the overwhelming desire on the part of the upper class to achieve public status worked both for and against the stability of the Republic. When this attitude motivated important men to seek office to promote the welfare of the population as a whole—the traditional ideal of a public career—it was a powerful force for social peace and general prosperity. But pushed to its logical extreme, as in the case of Sulla, an ambitious Roman’s concern with personal standing based on individual prestige and wealth could overshadow all considerations of public service. Sulla in 88 B.C. simply could not bear to lose the glory and status that a victory over Mithradates would bring. He therefore chose to initiate a civil war rather than to see his cherished status diminished. For all these reasons, the Republic was doomed once its leaders and their followers abandoned the “way of the elders” that valued respect for the common peace and prosperity and for shared government above personal gain and individual political power. For all these reasons, Sulla’s career reveals how the Republic’s social and political traditions contained the seeds of its own destruction, as the balance of values between individual success and communal well-being that was supposed to guarantee Rome’s safety and prosperity dissolved into violent conflict among Romans.

The famous generals whose ambitions sparked the war among Romans that destroyed the Republic took Sulla’s career as their model: while proclaiming they were working to preserve the state, they sought power for themselves above all else. Gnaeus Pompey (106 B.C.–48 B.C.) was the first of these leaders. Pompey forced his way into the ranks of Roman leaders in 83 B.C. when Sulla was first returning to Italy. Only twenty-three years old, far too young for leadership according to Roman tradition, Pompey gathered a private army from his father’s clients in Italy to join Sulla in his campaign to return to power in the capital. When Pompey defeated Sulla’s remaining enemies, who had fled to Sicily and North Africa, Sulla in 81 B.C. reluctantly allowed Pompey the extraordinary honor of celebrating a triumph. The celebration of a triumph by such a young man, who had never held even a single public office, shattered the Republic’s ancient tradition that men had to climb the ladder of offices before achieving such prominence. Pompey did not have to wait his turn for honor or earn his reward only after years of service. Because he was so powerful, he could demand his glory from Sulla on the spot. As Pompey brashly said to the older Sulla, “More people worship the rising than the setting sun” (Plutarch, Life of Pompey 14). The completely irregular nature of Pompey’s career betrayed the flimsiness of Sulla’s vision of the Roman state. Sulla had proclaimed a return to the rule of the “best people” and, according to him, Rome’s finest political traditions. Instead, he had fashioned a regime controlled by violence and power politics.

The history of the rest of Pompey’s career shows how the traditional checks and balances of politics in the Republic failed. After helping suppress a rebellion in Spain and a massive slave revolt in Italy led by the escaped gladiator Spartacus, Pompey demanded and received election as a consul for 70 B.C., well before he had reached the legal age of forty-two. Three years later, he was voted a command with unprecedented powers to fight the pirates currently infesting the shipping lanes of the Mediterranean Sea. He smashed them in a matter of months. This success made him wildly popular with the urban poor at Rome, who depended on a steady flow of grain imported by sea and subsidized by the state; with the wealthy merchants, who depended on safe sea transport for their goods; and with coastal communities everywhere, which suffered from the pirates’ raids. The next year the command against Mithradates, who was still causing trouble in Asia Minor, was taken away from the general Lucullus so it could be given to Pompey. Lucullus had made himself unpopular with his troops by curbing their looting of the province and with the tax collectors by regulating their extortion of the defenseless provincials. Pompey proceeded to conquer Asia Minor and other eastern lands in a series of bold campaigns. He marched as far south as Jerusalem, the capital and religious center of the Jews, which he captured in 63 B.C. When Pompey then annexed Syria as a province, he initiated Rome’s formal control of that part of southwestern Asia.

Pompey’s conquests in the eastern Mediterranean were spectacular. People compared him to Alexander the Great, and he was awarded the name Magnus, making him “Pompey the Great.” He boasted that he had caused Rome’s revenues from its provinces to skyrocket, and distributed money equal to twelve and a half years’ pay to his soldiers as their share of the booty. During his time in the east he operated largely on his own initiative. He never consulted the Senate when he made new political arrangements for the territory that he had conquered. For all practical purposes, he behaved like an independent king and not an official of the Roman Republic. Early in his career, he expressed the attitude that he relied on throughout his life: when some foreigners objected to his treatment as unjust, he replied, “Stop quoting the laws to us. We carry swords” (Plutarch, Life of Pompey 10).

The great military successes that Pompey won made his upper-class rivals at Rome both resent and fear him. Principal among them were two highly ambitious men, the fabulously wealthy Marcus Licinius Crassus, who had defeated the rebel slave leader Spartacus, and the young Julius Caesar (100–44 B.C.). To gain support against Pompey, they promoted themselves as populares, leaders dedicated to improving the lives of ordinary people. There was much to improve. The population of the city of Rome had soared to perhaps a million persons. Hundreds of thousands of its residents lived crowded together in shabby apartment buildings no better than slums. Work was hard to find. Many people subsisted on the grain distributed by the government. The streets of the city were dangerous, and Rome had no police force. To make matters worse, economic conditions by the 60s B.C. had become especially precarious, probably as the result of a bust following a boom in the value of property. Sulla’s confiscations of land and buildings by proscription had evidently created a much more speculative real estate market. Now, the market was flooded with mortgaged properties for sale, and prices were crashing. Credit seems to have been in short supply at this very time when those in financial difficulties over their property were trying to borrow their way back to respectability. Whatever their exact cause, these financial problems made life difficult and stressful even for many members of the equestrian and senatorial classes.

The conspiracy of Lucius Sergius Catilina in 63 B.C. reveals to what lengths the problems of debt and poverty could drive desperate members of the upper class. Catiline, as he is known, was a debt-ridden noble who rallied around himself a band of fellow upper-class debtors and victims of Sulla’s confiscations. Frustrated in his attempts to win election as a consul, he planned to use violence to achieve political power, with the announced goal of then redistributing wealth and property to his supporters after achieving victory. Cicero, one of the two consuls in 63 B.C., thwarted the plotters before they could murder him and the other consul. Catiline and his co-conspirators probably never had a realistic chance of redressing their grievances, even if they had seized the state, because the only way to redistribute property would have been to kill currently solvent property owners. Nevertheless, their futile effort demonstrates the level of violence that became typical of Roman politics in the mid-first century B.C.

When Pompey returned to Rome from the eastern Mediterranean in 62 B.C., the “best people” among the political leaders refused, out of jealousy of his fame, to support his territorial arrangements or authorize the distribution of land as a reward to the veterans of his army. This setback forced Pompey to make a political alliance with Crassus and Caesar. These three in 60 B.C. formed an informal troika, commonly called the First Triumvirate (“Association of Three Men”) to advance their own interests. They succeeded. Pompey got laws to confirm his eastern arrangements and give land to his veterans. Caesar was made consul for 59 B.C., receiving a special extended command in Gaul. Crassus got financial breaks for the Roman tax collectors in Asia Minor, whose support helped guarantee his political prominence and in whose profitable business he had a stake. This coalition of former political opponents provided each triumvir (member of the triumvirate) a means to achieve his own ambitions: Pompey wanted status from fulfilling his role as patron to his troops and to the territories that he had conquered, Caesar had an enormous ambition to gain the highest political office and the chance to win glory and booty from foreigners, and Crassus wanted to help his clients and himself financially so that he could remain politically competitive with the other two, whose reputations as generals far exceeded his. The First Triumvirate was a political creation that ignored the “Roman constitution.” It was formed only for the advantage of its members. Because they shared no common philosophy of governing, however, the triumvirs’ cooperation was destined to last only as long as they continued to profit personally from this tradition-shattering arrangement.

Recognizing the instability of their coalition, the triumvirs used a time-tested tactic to try to give it permanence: they contracted politically motivated marriages among one another. Women were the pawns traded back and forth in these alliances. In 59 B.C., Caesar married his daughter Julia to Pompey. She had been engaged to another man, but her father made this marriage take precedence over her previous commitment in order to create a bond between himself and Pompey. Pompey simultaneously soothed Julia’s jilted fiancé by having the man marry Pompey’s daughter, who had been engaged to yet somebody else. Through these marital machinations, the two powerful antagonists now had a common interest: the fate of Julia, Caesar’s only daughter and Pompey’s new wife. (He had divorced his second wife after Caesar allegedly had seduced her.) Despite their arranged marriage, Pompey and Julia by all reports fell deeply in love. So long as Julia lived, Pompey’s affection for her helped to restrain him from an outright break with her father, Caesar. But when she died in childbirth in 54 B.C. (and her baby soon after), the bond linking Pompey and Caesar ruptured beyond repair.

Julius Caesar was born to one of Rome’s most distinguished families; it claimed the goddess Venus as an ancestor. The intensity of Caesar’s ambitions matched the luster of his origins. He borrowed and spent huge sums of money to promote his political career and compete with Pompey to be Rome’s premier leader. As triumvir he left Rome to take up a command in Gaul in 58 B.C. For the next nine years he attacked people after people throughout what is now France, the western part of Germany, and even the southern end of Britain. The value of the slaves and booty that his army won was so huge that he was able not only to pay off his enormous debts but also enrich his soldiers. For this reason, his troops loved him, but also for his easy manner when talking with them and his willingness to undergo all the hardships and deprivations that they experienced on military campaign. His political rivals at Rome feared him even more as his military successes in Gaul mounted, while his supporters tried to prepare the ground for a safe and triumphant return to Rome.

The rivalry between Caesar’s friends and enemies at Rome culminated in bloodshed. By the mid-fifties B.C., politically motivated gangs of young men roamed the city’s streets, prowling for opponents to beat or murder. The street fighting reached such a pitch in 53 B.C. that it was impossible to hold elections, and no consuls were chosen for the year. The triumvirate fell apart that same year with the death of Crassus. In an attempt to win the military glory his career lacked, Crassus had led a Roman army across the Euphrates River to fight the Parthians, an Iranian people whose military aristocracy headed by a king ruled a vast territory stretching from the Euphrates to the Indus River. When Crassus died in battle at Carrhae in northern Mesopotamia, the alliance between Pompey and Caesar also came to an end. In 52 B.C., Caesar’s enemies succeeded in having Pompey appointed as sole consul for the year, an outrage against the traditions and values of the “Roman constitution.” When Caesar prepared to return to Rome in 49 B.C., he too wanted a special arrangement to protect himself: to be made consul for 48 B.C.

The response of the Senate to Caesar’s demand was to order him to surrender his command. Instead, Caesar, like Sulla before him, led his army against Rome. As he crossed the Rubicon River in northern Italy in early 49 B.C., he uttered (in Greek) the words that signaled the start of a civil war: “Let’s roll the dice!” (Plutarch, Life of Julius Caesar 39, Life of Pompey 60; Appian, Civil War 2.35; Suetonius, Life of Julius Caesar 32 has “The die is cast!”). His troops followed him without hesitation, and most of the people of the towns and countryside of Italy cheered him on enthusiastically. He had many backers in Rome, too, especially those to whom he had lent money or given political support. Some of those who were glad to hear of his coming were ruined nobles, who hoped to recoup their once-great fortunes by backing Caesar against the rich. These were in fact the people whom Caesar had always refused to help politically or financially, saying to them, “What you need is a civil war!” (Suetonius, Life of Julius Caesar 27).

The enthusiastic response of the masses to Caesar’s advance surprised Pompey and the rest of Caesar’s enemies in the Senate. In a panic, they transported the soldiers loyal to them to Greece for training before facing Caesar’s more experienced troops. Caesar entered Rome peacefully, but soon departed to defeat the army that his enemies had in Spain. In 48 B.C. he then sailed across the Adriatic Sea to Greece to force a decisive battle with Pompey. There he nearly lost the war when Pompey cut off his supplies with a blockade. But Caesar’s loyal soldiers stuck with him even when they were reduced to eating awful bread made from forest grasses and roots mixed with milk. When Caesar’s men ran up to Pompey’s outposts and threw some of their primitive food over the wall while shouting out that they would never stop fighting so long as the earth produced roots for them to gnaw, Pompey said in horror, “I am fighting wild animals!” (Suetonius, Life of Julius Caesar 68). He prevented the food from being shown to his troops, fearing that his men would lose their courage if they found how out how tough Caesar’s soldiers were.

The high morale of Caesar’s army and Pompey’s surprisingly weak generalship eventually combined to bring Caesar a crushing victory at the battle of Pharsalus in central Greece in 48 B.C. Pompey fled to Egypt, where he was treacherously murdered by the ministers of the boy-king Ptolemy XIII, who had earlier exiled his sister and wife, Queen Cleopatra VII, and had supported Pompey in the war. Caesar won a difficult campaign in Egypt that ended with the drowning of the pharaoh in the Nile and the return to the Egyptian throne of Cleopatra, who had begun a love affair with the Roman conqueror. He next had to spend three years in hard fighting against enemies in Asia Minor, North Africa, and Spain. In writing to a friend about one of his victories in this period of frequent battles, he penned his famous three words: Veni, vidi, vici (“I came, I saw, I conquered!” Suetonius, Life of Julius Caesar 37). By 45 B.C. there was no one left to face him on the battlefield.

The field of politics proved to be more dangerous for Julius Caesar than the battlefield. After his victory in the civil war, Caesar faced the dilemma of how to govern a politically fractured Rome. The problem confronting him had deep roots. Recent experience seemed to show that only a sole ruler could put an end to the chaotic violence of the divided politics of first-century B.C. Rome. The oldest upper-class tradition of the Republic, however, was hatred for monarchy. Cato the Elder had expressed this feeling best: “A king,” he quipped, “is a beast that feeds on human flesh” (Plutarch, Life of Cato the Elder 8).

Caesar’s solution to the dilemma was to rule as a king in everything but name. He began by having himself appointed dictator in 48 B.C. By 44 B.C., he had removed any limitation on his term in this traditionally temporary office, becoming, as his coins expressed it, “Dictator Always” (dictator perpetuo; see Crawford nos. 480/6ff.). He insisted that “I am called Caesar, not King” (Plutarch, Life of Julius Caesar 60), but the distinction was truly meaningless. As dictator without any limit of time to his term in the office, he personally controlled the government despite the appearance of normal procedures. It is unclear what kind of government Caesar expected to exist in the long term. With no son of his own, in September 45 B.C. he had made a new will designating his grandnephew Gaius Octavius (63 B.C.-A.D. 14) his heir and adopted son. As was customary upon adoption, the young man changed the ending of his name Octavius to Octavian, the name by which he is known today in the period before he eventually became Rome’s first emperor as Augustus. Whether Caesar himself somehow expected Octavius in time to take over as ruler of Rome is not recorded.

In the meantime, elections for offices continued, but Caesar determined the results by recommending candidates to the assemblies, which his supporters dominated. Naturally his recommendations were followed. His policies as Rome’s sole ruler were ambitious and broad. He reduced debt moderately, limited the number of people eligible for subsidized grain, initiated a large program of public works including the construction of public libraries, established colonies for his veterans in Italy and abroad, rebuilt and repopulated Corinth and Carthage to become commercial centers, proclaimed standard constitutions for Italian towns, and extended citizenship to non-Romans, such as the Gauls in northern Italy. He also admitted non-Italians to the Senate when he expanded its membership from six hundred to nine hundred. Unlike Sulla, he did not proscribe his enemies. Instead, he prided himself on his clemency, whose recipients were, by Roman tradition, obliged to become his grateful clients. In return, Caesar received unprecedented honors, such as a special golden seat in the Senate House and the renaming of the seventh month of the year after him (Julius, hence its name, July). He also regularized the Roman calendar by initiating a year of 365 days, which was based on an ancient Egyptian calendar and forms the basis for the modern calendar.

Julius Caesar’s dictatorship and his honors pleased most ordinary people but outraged the “best people.” This upper-class group saw themselves as largely excluded from power and dominated by one of their own, who, they believed, had deserted to the other side in the perpetual conflict between the Republic’s rich and poor. A band of nobles conspired to stab Caesar to death in 44 B.C. on 15 March (the Ides of March, as that day was called in the Roman calendar). The “Liberators,” as the conspirators against Caesar called themselves, had no specific plans for governing Rome following the murder. They apparently believed that the traditional political system of the Republic would somehow resume without any further action on their part and without more violence. This faith can only be called simple-minded, to say the least. These self-styled champions of traditional Roman liberty were ignoring the disruptive effect of the turbulent history of the previous forty years from the time of Sulla. In fact, rioting broke out at the funeral of Caesar when the masses vented their anger against the upper class that had robbed them of their hero. Far from presenting a united front, the nobles resumed their struggles with one another to secure political power. Another civil war of great ferocity began following Caesar’s death. The Republic, plainly, had been damaged beyond repair by this date. From the ashes of this struggle gradually emerged the disguised monarchy—that we call the Roman Empire but the Romans still called the Republic—under which the rest of Rome’s history would unroll in the centuries to come.

Figure 15. A coin shows Brutus, one of the conspirators who murdered Julius Caesar, and symbols of the “liberation” they claimed to perform on the Ides of March 44 B.C. The daggers implied that violence was justified to remove a tyrant, while the cap symbolized the freedom from tyranny that the conspirators believed they restored through their deed. Photo courtesy of Classical Numismatic Group, Inc./www.cngcoins.com.

It seems fitting to close with a glance at the stark realism of literature and of sculptural portraiture in this violent period because it can hardly be an accident that they appear to reflect the strain and the sadness of social and political life in a Republic that was committing suicide. Historians must necessarily be cautious about postulating overly specific connections between authors’ and artists’ works and the events of their times because the sources of creativity are so diverse. There is no doubt, however, that contemporary literature directly reflected on the catastrophe of the late Republic. In the work of other creative artists, such as sculptors of portraits, we can suspect a connection to the tumultuous and depressing conditions of the times.

Contemporary references to events and leading personalities in Rome appear in the poems of Catullus (c. 84 B.C.–54 B.C.). He moved to Rome from his home in the province of Cisalpine Gaul in northern Italy, where his family had been prominent enough to host Julius Caesar when he had been governor there. That connection did not prevent Catullus from including Caesar among the politicians of the era whose sexual behavior he made fun of with his witty and explicit poetry. Catullus also wrote poems on more timeless themes, love above all. He employed a literary style popular among a circle of poets who modeled their Latin poems on the elegant Greek poetry of Hellenistic-era authors such as Callimachus. Catullus’s most famous series of love poems concerned his passion for a married woman named Lesbia, whom he begged to think only of the pleasures of the present: “Let us live, my Lesbia, and love, and value at one penny all the talk of stern old men. Suns can set and rise again: we, when once our brief light has set, must sleep one never-ending night. Give me a thousand kisses, then a hundred, then a thousand more…” (Poem 5). Catullus’s call to live for the moment, paying no attention to conventional moral standards, suited this period when the turmoil at Rome could make the concerns of ordinary life seem irrelevant.

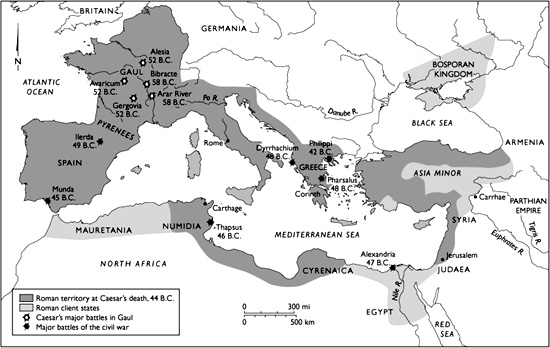

Map 6. The Roman World at the End of the Republic

The many prose works of Cicero, the master of rhetoric, also often directly concerned events of his time. Fifty-eight of his speeches survive in the revised versions he published, and their eloquence and clarity established the style that later European prose authors tried to match when writing polished Latin—the common language of government, theology, literature, and science throughout Europe for the next thousand years and more. Cicero also wrote many letters to his family and friends in which he commented frankly on political infighting and his motives in pursuing his own self-interest. The nine hundred surviving letters offer a vivid portrait of Cicero’s political ideas, joys, sorrows, worries, pride, and love for his daughter. For no other figure from the ancient world do we have such copious and revealing personal material.

During periods when Cicero had to withdraw temporarily from public affairs because his political opponents threatened his safety, he wrote numerous works on political science, philosophy, ethics, and theology. Taking his inspiration mainly from Greek philosophers, Cicero adapted their ideas to Roman life and infused his writings on these topics with a deep understanding of the need to appreciate the uniqueness of each human personality. His doctrine of humanitas (“humanness, the quality of humanity”) combined various strands of Greek philosophy, especially Stoicism, to express an ideal for human life based on generous and honest treatment of others and an abiding commitment to morality derived from natural law (the rights that exist for all people by nature, independent of the differing laws and customs of different societies). This ideal exercised a powerful and enduring influence on later Western ethical philosophy. Cicero’s philosophical thought and the style of his Latin prose, not his political career, made him a central figure in the transmission to later ages of perhaps the most attractive ideal to come from ancient Greece and Rome.

The poet Lucretius (c. 94 B.C.–55 B.C.) provides an example of an author indirectly reflecting the uncertainty and violence of his times. By explaining the nature of matter as composed of tiny, invisible particles called atoms, his long poem On the Nature of Things sought to end people’s fear of death, which, in his words, served only to feed “the running sores of life.” Death, his poem taught, simply meant the dissolving of the union of atoms, which had come together temporarily to make up a person’s body. There could be no eternal punishment or pain after death, indeed no existence at all, because a person’s soul, itself made up of atoms, perished along with the body. Lucretius took this so-called atomic theory of the nature of existence from the work of the Greek philosopher Epicurus (341 B.C.–270 B.C.), whose views on the atomic character of matter were in turn derived from the work of the fifth-century B.C. thinkers Leucippus and Democritus. Although we do not know when he began to compose his poem, Lucretius was still working on it at Rome during the 50s B.C., when politically motivated violence added a powerful new threat to life in Rome. Romans in Lucretius’s time had good reason to need reassurance that death had no sting.

We can also speculate that the starkly realistic style of Roman portraiture of men in the first century B.C. expressed the recognition of life’s harshness in this violence-plagued period. The many Roman portraits of individual men that survive from this era did not try to hide unflattering facial features and expressions. Long noses, receding chins, deep wrinkles, bald heads, tired and worn faces—all these appeared in sculpted portraits. The Roman upper-class tradition of making death masks of ancestors and displaying them in their homes presumably contributed to this style of portraiture. Portraits of women from the period, by contrast, were generally more idealized, and children were not portrayed until the early Empire. Since either the men depicted by the portraits or their families paid for these portraits in stone, they must have wanted their hard experience of life to show in their faces. It is hard not to imagine that this insistence on realism mirrored the toll exacted on men who participated in the brutal arena of politics in the late Republic. These men had lived in the period that saw the final corruption of the finest values and ideals of the Republic. In their time a new ideal had emerged: that a Roman leader could never have too much glory or too much money, goals that trumped the tradition of public service to the commonwealth. The strain on their faces reflected the stress and sadness that the destruction of the Republic inflicted on so many Romans.