Augustus’s transformation of Roman government brought two centuries of relatively calm prosperity referred to as the Roman Peace (Pax Romana). Historians rank the second century A.D. as the Golden Age of the Roman Empire. As a de facto monarchy, however, the “Restored Republic” always faced the threat of a violent struggle for power among the elite. In fact, it seemed likely that a civil war might erupt after Augustus died because there was no precedent for how to pass on rule under this new system. Augustus’s fiction that the Republic still existed meant that the rulership did not automatically pass to a son as his successor, as it would in an acknowledged kingdom. At the same time, he wanted to determine who would become Rome’s next ruler and make it someone close to him. Having no son of his own, he adopted Tiberius, an adult son of his wife Livia by her previous marriage. Tiberius was famous for his brilliant military record, and Augustus informed the Senate that the army wanted this adoptive son to be in line to become the next princeps. The senators prudently confirmed Augustus’s choice in this position after the first emperor died. Members of Augustus’s family—known as the Julio-Claudians from the names of the family lineages of Augustus (the Julians) and Tiberius (the Claudians)—continued to fill the post of “First Man”—thereby becoming “emperors”—for the next half-century, always with the formal approval of the Senate.

14–37: Tiberius, the first Roman emperor of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, rules until his (probably) natural death.

23: Tiberius builds a permanent camp in Rome for the Praetorian Guard.

37–41: Gaius (Caligula) rules as Roman emperor until he is murdered.

41: The Praetorian Guard blocks the Senate from reestablishing the old Republic and makes Claudius the emperor.

41–54: Claudius rules as Roman emperor until he is murdered.

54–68: Nero rules as Roman emperor until he commits suicide; his death ends the Julio-Claudian dynasty.

69: Vespasian wins a civil war and creates the Flavian dynasty of emperors; he rules until his natural death in 79.

70: Titus, Vespasian’s son, captures Jerusalem, ending a four-year Jewish rebellion.

79–81: Titus rules as Roman emperor until his natural death.

79: The volcano Vesuvius erupts, burying Pompeii and Herculaneum in southern Italy.

80: Titus has the Colosseum finished at Rome.

81–96: Domitian, Vespasian’s son, rules until he is murdered.

96–180: The Five Good Emperors (Nerva, Trajan, Hadrian, Antoninus Pius, and Marcus Aurelius) rule during the Roman Empire’s political Golden Age.

113: Trajan erects his sculpted victory column at Rome.

125: Hadrian finishes construction on the domed Pantheon in Rome.

Late second century: The sculpted victory column of Marcus Aurelius is erected at Rome.

The goals of the Julio-Claudian dynasty (the succession of rulers related to one another) included preventing unrest, building loyalty, and financing their administrations. These emperors oversaw a vast territory of provinces populated by a mix of Roman citizens and local populations. Therefore, the emperors took special care of the army, encouraged religious rituals dedicated to the welfare of the imperial household, and promoted Roman law and culture as universal standards while allowing as much local freedom as possible. Their subjects expected the emperors to be generous patrons rewarding their faithful loyalty to the regime, but the difficulties of long-range communication and the low level of technology limited the emperors’ ability to care for the inhabitants of the empire.

The greatest challenge facing the Julio-Claudian emperors after Augustus—Tiberius, Gaius (Caligula), Claudius, and Nero—was how to keep the Principate functioning peacefully and prosperously. With nothing to guide them except Augustus’s example, they had to protect Roman territory from foreign enemies, prevent the elite from conspiring to replace them, keep the people content, and resist the personal temptations of supreme power. Some emperors governed better than others, but by the end of Nero’s reign, no Roman seriously believed that family dynasties of emperors would not continue to rule the Roman Empire. To understand how this great change took place, it is necessary to survey briefly the reigns of the Julio-Claudian emperors following Augustus.

Tiberius (42 B.C.–A.D. 37) held power for twenty-three years after Augustus’s death in A.D. 14 because he had the most important qualifications for succeeding as princeps: a family connection to Augustus and a brilliant record as a general earning him the respect of the army. He paid a steep personal price for becoming Augustus’s successor as emperor: to strengthen their family ties, his new father had forced Tiberius to divorce his beloved wife, Vipsania, to marry Augustus’s daughter, Julia. This political marriage proved disastrously unhappy. Tiberius never recovered from this sadness, and he was a reluctant ruler, so bitter at his fate that he spent the last decade of his life as a recluse in a palace at the top of a cliff on the island of Capri near Naples, never again returning to Rome.

Despite Tiberius’s infamously bitter frame of mind and his deep unpopularity with the Roman populace, his long reign provided the stable transition period that the Empire needed to become established as a compromise in governing between the emperor and the elite. Despite ruling essentially as a monarch, the emperor still needed the cooperation of the upper class as officials in the imperial administration, commanders in the army, and leaders and financial contributors in local communities in the provinces. So long as this compromise endured, the Empire could thrive and both sides could enjoy status and respect. On the one hand, the elite could continue to bask in the prestige of their traditional roles as consuls, praetors, senators, and high-ranking priests. On the other, the emperors could make their superior status clear by deciding who would fill these positions, assuming the power formerly held by the Assemblies. These meetings soon became rubberstamps for the emperors’ wishes and eventually withered away. In sum, the government of the Empire was a negotiated settlement between members of the upper class. In A.D. 23 Tiberius also built a permanent camp in the city for the Praetorian Guard, making it easier to use them in supporting him with force if necessary. He died in his bed of natural causes, it seems, although there was a rumor that he was smothered. He was so unpopular that the news of his death caused rejoicing in the streets.

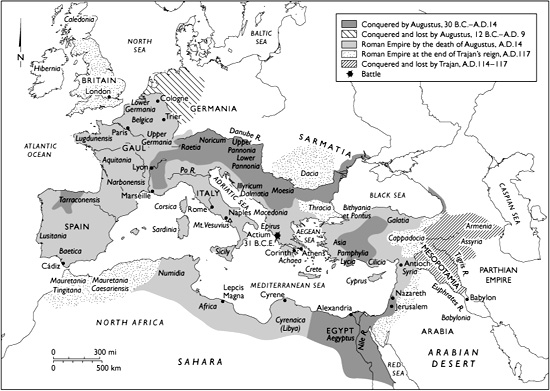

Map 7. Roman Expansion During the Early Empire

The next Julio-Claudian emperor, Gaius, known as Caligula (A.D. 12–41), had a fatal shortcoming: he enjoyed his power too much and never made a career as a military leader. Tiberius had chosen him as his successor because he was the great-grandson of Augustus’s sister. Gaius could have been successful because he was wildly popular at first and also knew about soldiering: Caligula means “Baby Boots,” the nickname the troops gave him as a child because he wore little leather shoes imitating theirs while he lived in military camps where his father was a commander. Unfortunately, he soon showed that he lacked the personality for leadership when given unbridled power; what he did possess were extravagant desires for personal dissipation. Ruling through cruelty and violence, he overspent from the treasury to humor his cravings and, to raise money, imposed new sales taxes on everything from the fast food sold in Rome’s many take-out shops to each sex act performed by a prostitute. Caligula outraged the value of dignified conduct expected of a member of the social elite by appearing on stage as a singer and actor, fighting mock gladiatorial combats, appearing in public in women’s clothing or costumes imitating gods, and, it seems likely, having sexual affairs with his sisters. His abuses finally went too far: two soldiers in the Praetorian Guard murdered him in A.D. 41 to avenge his insults to them.

The murder of Caligula threatened to end the Julio-Claudian dynasty because Gaius had no son and his violent behavior had frightened everyone around him. When his murder was announced, some senators proclaimed that it was time to bring back the original Republic and true liberty. The Praetorian Guard overthrew this plan, however, because they wanted emperors to continue so as to be their patrons. The soldiers in the city therefore literally dragged Augustus’s relative Claudius (10 B.C.– A.D. 54), now fifty years old and never considered to be capable of rule, to their camp and forced the Senate to acknowledge him as the new ruler. The threat to use force to get what they wanted made it clear that the soldiers, whether praetorians in Rome or troops in the legions, would always insist on having an emperor. It also revealed that any senatorial yearnings for the return of a true Republic had no chance of being ever fulfilled.

Claudius surprised everyone by ruling competently overall. He set a crucial precedent for imperial rule by enrolling men from a province (Transalpine Gaul, meaning southeastern France) in the Senate for the first time. This change opened the way for the growing importance of provincials as the emperors’ clients, whose role was to help keep the empire peaceful and prosperous. Claudius also changed imperial government by employing freed slaves as powerful administrators; since they owed their great advancement to the emperor, they could be expected to be loyal.

Claudius’s wife Agrippina poisoned him in A.D. 54 because she wanted Nero (A.D. 37–68), her teenaged son by a previous husband, to become emperor instead of Claudius’s own son. Nero, like Caligula, succumbed to the glorious temptations of absolute power. Having received no military training or preparation for governing, Nero had a passion for music and acting, not for administering an empire. The spectacular public festivals he put on and the cash he distributed to the masses in Rome kept him popular with the poor, although a giant fire in the city in A.D. 64 aroused suspicions that he might have ordered the conflagration to clear the way for new building projects. Nero spent outrageous sums on his pleasures. To raise more money, he trumped up charges of treason against wealthy men and women to seize their property. Alarmed and outraged, commanders in the provinces turned against him and supported rebellion, as did many senators. When one of the praetorians’ commanders bribed them to desert the emperor, Nero had no defense left. Fearing arrest and execution, Nero shouted in dismay, “To die! And such a great artist!” Not long after he had a servant help him cut his own throat (Suetonius, Life of Nero 49).

With no successor to the childless Nero in the palace, a civil war began in A.D. 68 between different rivals to the throne. The winner of the conflict among four rivals for the throne in the following “Year of the Four Emperors” (A.D. 69) was the general Vespasian (A.D. 9–79). He installed his family, the Flavians, as the new imperial dynasty to succeed the Julio-Claudians. To create political legitimacy for this new regime, Vespasian had the Senate recognize him as ruler with a detailed statement of the powers that he held, which were made into a law and explicitly said to come down to him from the precedents of the powers of his worthy predecessors as “First Men” (a list that excluded Caligula and Nero). To encourage loyalty in the provinces, he encouraged the elites there to take part in the so-called “imperial cult” (rituals that focused on sacrificing animals to the traditional gods for the welfare of the emperor and his family and, in some cases, actual worship of the emperor).

Figure 19. This street at Herculaneum, preserved by the eruption of Vesuvius in A.D. 79, is lined by multistoried and balconied houses typical of Roman towns. Windows and porches in the upper stories provided light, ventilation, and space to combat the crowding and smells of the streets below. Alinari/Art Resource, NY.

Vespasian built on local traditions in the eastern provinces in promoting the imperial cult. The deification of the current ruler seemed normal to the provincials there because they had been honoring local kings as divinities for centuries, going back to the time of Alexander the Great in the late fourth century B.C. The imperial cult communicated the same image of the emperor to the people of the provinces as the city’s architecture and sculpture did to the people of Rome: he was larger than life, worthy of loyal respect, and the source of benefactions as their patron. Because emperor worship had already become better established in the eastern part of the empire under Augustus, Vespasian concentrated on strengthening it in the provinces of Spain, southern France, and North Africa. Italy, however, still had no temples to the living emperor, and traditional Romans there scorned the imperial cult as a provincial peculiarity. Vespasian, known for his wit, even skeptically muttered as he lay dying in A.D. 79, “Poor me! I’m afraid I’m becoming a god” (Suetonius, Life of Vespasian 23).

Vespasian’s sons Titus (A.D. 39–81) and Domitian (A.D. 51–96) continued the dynasty, dealing with two problems that would increasingly occupy future emperors: improving life for people throughout the empire to prevent disorder, and defending against invasions from peoples on the frontiers. Titus had become famous in A.D. 70 for defeating a four-year rebellion by Jews in what is today Israel and capturing Jerusalem, where the Jewish Temple, the ritual center of Judaism, was burned down in the attack, never to be rebuilt. In his brief time as emperor (A.D. 79–81), Titus sent relief to the communities damaged by the volcanic eruption of Mount Vesuvius in A.D. 79; the gigantic quantity of ash and volcanic mud spewed out by the exploding mountain preserved large parts of the neighboring towns of Pompeii and Herculaneum. This disaster that killed and displaced so many people made those sites into uniquely rich sources for us because it froze in time so many specimens of the architecture, painting, and mosaics of the era.

Titus also provided the public with a state-of-the-art site for lavish public entertainments by finishing Rome’s Colosseum (or Coliseum) in A.D. 80, outfitting it with giant awnings to shade the crowd. Following his brother’s death from natural causes, Domitian as emperor (A.D. 81–96) led the army north to the Rhine and Danube River areas to fight off Germanic invaders, the beginning of a danger that was going to plague the empire for centuries. His arrogance made him disliked at home. For example, in communicating his wishes in writing and in conversation he customarily said, “Our Master and God, myself, orders you to do this” (Suetonius, Life of Domitian 13). He also emphasized his superiority over everyone else by expanding the imperial palace on the Palatine Hill to more than 350,000 square feet. Fearing Domitian was going to eliminate them, a group of conspirators from his court murdered him after fifteen years of rule.

By now, the murder of an emperor meant only that a new one needed to be found who satisfied the army, not that the system of government might change. As the historian Tacitus (A.D. 56–118) wrote, emperors had become like the weather; their extravagance and greed for domination had to be endured just as drought or floods did (Histories 4.74). A better political climate prevailed in the empire under the next five emperors—Nerva (ruled A.D. 96–98), Trajan (ruled 98–117), Hadrian (ruled 117–138), Antoninus Pius (ruled 138–161), and Marcus Aurelius (ruled 161–180). Historians have designated their reigns as the empire’s political Golden Age because these rulers provided peace and quiet for nearly a century. Of course, “peace” is a relative term in Roman history: Trajan fought fierce campaigns that expanded Roman power northward across the Danube River into Dacia (today Romania) and eastward into Mesopotamia (Iraq), Hadrian punished a second Jewish revolt by turning Jerusalem into a military colony, and Aurelius spent many miserable years protecting the Danube region from outside attacks.

Figure 20. Soldiers on a victory column erected by Emperor Marcus Aurelius in Rome have equipment typical of the Roman army in the early Empire. The continuous sculpted bands winding around this and similar monuments provide a wide array of scenes of the imperial army in battle, in camp, and on parade. Barosaurus Lentus/Wikimedia Commons.

Still, the idea of a Golden Age under the “Five Good Emperors” makes sense, at least compared to the violence of the late Republic and the murderous history of the Julio-Claudians. These five rulers succeeded each other without assassination or conspiracy—indeed, the first four, having no sons, used the Roman tradition of adopting adults to find the best possible successor. Moreover, adequate revenue was coming in through taxes, the army remained obedient, and overseas trade reached its greatest heights. Chinese records even show that a group of Roman merchants apparently claiming to bring the greetings of the Roman emperor reached the court of the Han emperor during the reign of Marcus Aurelius (Schoff, pp. 276–277). These reigns marked the longest stretch in Roman history without a civil war since the second century B.C.

The peace and the prosperity of the second century A.D. depended on defense by a loyal and efficient military, public-spiritedness among provincial elites in local administration and tax collection, the spread of common laws and culture to promote unity throughout huge and diverse territories, and a healthy population reproducing itself. The great size of the Roman Empire, combined with the enduring conditions of ancient life, meant that emperors had less control over these factors than they would have liked.

In theory, Rome’s military goal remained infinite expansion. Vergil in the Aeneid (2.179) had expressed this notion by portraying Jupiter, the king of the gods, as promising the Romans “rule without limit.” In reality, the empire’s territory never expanded much beyond what Augustus had established, encircling the Mediterranean Sea; Trajan’s conquest of Mesopotamia had to be given up by Hadrian as too difficult to defend. Most emperors had to concentrate on defense and maintaining internal order, only dreaming of further conquest.

Most provinces were stable and peaceful in this period and had no need for garrisons of troops. Roman soldiers were therefore a rare sight in many places. Even Gaul, which in Julius Caesar’s time had resisted Roman control with a suicidal frenzy, was, according to a contemporary witness, “kept in order by 1,200 troops—hardly more soldiers than it has towns” (Josephus, The Jewish War 2.373). Most Roman troops were concentrated on the northern and eastern fringes of the empire, where powerful and sometimes hostile neighbors lived just beyond the boundaries and the distance from the center weakened the local residents’ loyalty to the imperial government.

Now that Rome was no longer fighting wars of conquest, it became difficult to pay the costs of the military. In the past, successful foreign wars had been an engine of prosperity because they brought in huge amounts of capital through booty, indemnities, and prisoners of war sold into slavery. Conquered territory converted into provinces also provided additional tax revenues. Now, there were no longer any such opportunities to increase the government’s income, but the standing army still had to be paid regularly to maintain its loyalty. To fulfill their obligations as patrons of the army, emperors supplemented soldiers’ regular pay with substantial bonuses on special occasions. The financial rewards made a military career desirable, and enlistment counted as a privilege restricted to free male citizens. The army also included many auxiliary units of non-citizens fighting as cavalry, archers, and slingers. Serving under Roman commanders, the auxiliaries learned the Latin language and Roman customs. Upon discharge, they received Roman citizenship. In this way, the army served as an instrument for spreading a common way of life.

A tax on agricultural land in the provinces (Italy was exempt) provided the principal source of revenue for imperial government and defense. The provincial administration cost relatively little because the number of officials was small compared to the size of the empire being governed: no more than several hundred government officials governed a population of around 50 million. As under the Republic, governors with small personal staffs ran the provinces, which eventually numbered about forty. In Rome, the emperor employed a substantial palace staff, while officials called prefects managed the city itself.

The tax system required public service by the provincial elites in order to work; the empire’s revenues absolutely depended on these members of the upper class. They collected taxes as a required duty as unsalaried officials (curiales) on their city’s council (curia). In this decentralized system, these wealthy people were personally responsible for sending each year’s amount of tax to the central administration. If there was any shortfall, the officials had to make up the difference from their own pockets. Most emperors under the early Empire attempted to keep taxes from rising. As Tiberius put it once when refusing a request for tax increases from provincial governors, “I want you to shear my sheep, not skin them alive” (Suetonius, Life of Tiberius 32). Over time, however, the government’s need for more revenue grew more insistent, and the provincial elites found themselves hard-pressed to deliver.

The elites’ responsibility for tax collection could make civic office expensive, but the prestige and influence with the emperor that the positions carried made many provincials willing to shoulder the cost. Some received priesthoods in the imperial cult as a reward, an honor open to both men and women. Curiales could hope that the emperors would respond to their requests for special help for their areas, for example after an earthquake or a flood.

This system of financing the empire worked because it was rooted in the tradition of the patron-client system: the local social elites were the patrons of their communities but the clients of the emperors. As long as there were enough rich and public-spirited provincials responding to this value system that offered status as its reward, the empire could function by fostering the ancient Roman ideal of privileging communal values over individual comfort. The system was increasingly coming under pressure, however, because the costs of national defense kept rising, reflecting the need to defend against the growing threats from external enemies along the frontiers.

The Roman Empire changed the Mediterranean world profoundly but unevenly in a process that historians label “Romanization,” meaning the adoption of Roman culture by non-Romans. The empire’s provinces contained a wide diversity of peoples speaking different languages, observing different customs, dressing in distinctive styles, and worshiping various divinities. In the remote countryside, stability in life and customs prevailed because Roman conquest had little effect on local people. In the many places where new cities sprang up, however, change stemming from Roman influence was easy to see. These communities grew from the settlements of army veterans the emperors had sprinkled throughout the provinces, or they sprouted spontaneously around Roman forts. These settlements became particularly influential in Western Europe, permanently rooting Latin (and the languages that would emerge from it) and Roman law and customs there. Prominent modern cities such as Trier and Cologne near Germany’s western border started as Roman towns. Over time, the social and cultural distinctions weakened between the provinces and Italy, the Roman heartland. Eventually, emperors came from the provinces. Trajan, whose family had settled in Spain, was the first.

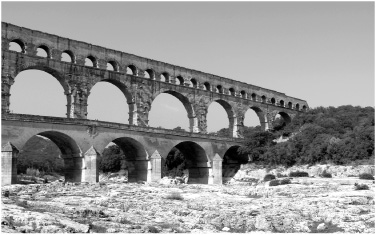

Romanization raised the standard of living for many provincials as transportation improved with the building of more roads and bridges and long aqueducts supplied fresh water to cities. Trade increased, including direct commercial interaction with markets as far away as India and China, where Roman merchants began to sail to find goods to import to Europe. Taxes on this international trade became a major source of revenue for the imperial government. Agriculture in the provinces flourished under the peaceful conditions secured by the army. Where troops were stationed in the provinces, their need for supplies meant new business for farmers and merchants. That the provincials for the most part lived more prosperously under Roman rule than they ever had before made it easier for them to accept Romanization. In addition, Romanization was not a one-way street culturally. In western provinces as diverse as Gaul, Britain, and North Africa, interaction between provincials and Romans produced new, mixed cultural traditions, especially in religion and art. This process led to a gradual merging of Roman and local culture, not the unilateral imposition of the conquerors’ way of life on provincials.

Figure 21. This gigantic stone bridge carried an aqueduct bringing fresh water from sources in the hills miles away to a large town in Gaul (today France). Engineers carefully calculated the proper slope for the channel so that water flowed continuously downhill to the urban center at a steady but manageable rate. Ad Meskens/Wikimedia Commons.

Romanization had less effect on the eastern provinces, which largely retained their Greek and western Asian character. When Romans had gradually taken over the region during the second and first centuries B.C., they found stable urban cultures there that had been flourishing for thousands of years. Huge cities such as Alexandria in Egypt and Antioch in Syria rivaled Rome in size and splendor. In fact, they boasted more individual houses for the well-to-do, fewer blocks of high-rise tenements, and equally magnificent temples. While retaining their local languages and customs, the eastern social elites easily accepted the “emperor as patron, themselves as clients” nature of provincial governance: they had long ago become accustomed to such a system through the comparable paternalistic relationships that had characterized the kingdoms under whose governments they had lived before the arrival of the Romans. The willing cooperation of these local, non-Roman elites in the task of governing the empire was crucial for its stability and prosperity.

In much of the eastern empire, then, daily life continued to follow traditional local models. The emperors lacked any notion of themselves as missionaries who had to impose Roman civilization on foreigners. Rather, they saw themselves primarily as preservers of law and social order. Therefore, they were happy for long-standing forms of eastern civic life and government to continue largely unchanged, so long as they promoted social stability and therefore internal peace.

The continuing vitality of Greek culture and language in bustling eastern cities contributed to a flourishing in literature in that language. New trends were especially notable in Greek prose. Second-century A.D. authors such as Chariton and Achilles Tatius wrote romantic adventure novels that began the enduring popularity of that kind of story as entertainment. Lucian (A.D. 117–180) composed satires and fantasies that fiercely mocked stuffy people, frauds, and old-fashioned gods. The essayist and philosopher Plutarch (A.D. 50–120) wrote biographies that matched Greek and Roman leaders in comparative studies of their characters. His keen moral sense and lively taste for anecdotes made him favorite reading for centuries. Shakespeare based several plays on Plutarch’s biographies.

Latin literature thrived as well. In fact, scholars rank the late first and early second centuries A.D. as its “Silver Age,” second in its production of masterpieces only to the literature of the Augustan literary Golden Age. The most famous Latin authors of this later time wrote with acid wit, verve, and imagination. The historian Tacitus (A.D. 56–120) composed a biting narrative of the Julio-Claudians, laying bare the ruthlessness of Augustus and the personal weaknesses of his successors. The satiric poet Juvenal (A.D. 65–130) skewered pretentious Romans and grasping provincials, while hilariously bemoaning the indignities of living broke in the city. Apuleius (A.D. 125–170) scandalized readers with his Golden Ass, a lusty novel about a man turned into a donkey, who then miraculously regains his body and his soul through salvation by the kindly Egyptian goddess Isis.

Large-scale architecture flourished in Rome during the first centuries of the Empire because the emperors saw large-scale building projects as a way to win public goodwill and broadcast their image as successful and caring rulers. For instance, the emperor Domitian in the first century A.D. built a stadium with a running track for athletic events to provide another large venue for public entertainment. Even more popular than these contests were the many theatrical performances, from drama to mime, that filled the Roman calendar of events.

The most impressive surviving example of these imperial monuments comes from the Golden Age of the second century A.D. This is the giant domed building called the Pantheon (meaning “All the Gods”; the building’s precise function remains unclear). Like Domitian’s stadium, the Pantheon was located just outside Rome’s center in the area known as the Field of Mars (Campus Martius). The emperor Hadrian had the Pantheon constructed from A.D. 118 to 125, on the site of earlier buildings that had burned down. The diameter of its rotunda is the same (nearly 150 feet) as the height of its dome, making its interior space a perfect half-sphere. It has stood for nearly two thousand years largely intact because Roman engineers made its outer brick structure so thick and interlocking. Hadrian also built himself a dazzling estate on the outskirts of Rome (today near the town of Tivoli), whose countless rooms, many statues, and architectural design were meant to recall the most famous monuments of the Greek and Roman world that he had seen on his many trips around the empire. We can be sure that it contained many paintings as well because that form of art remained immensely popular, but as elsewhere the passage of time has destroyed artistic creations such as paintings that were made from organic materials.

In financing such massive construction, Hadrian was following in the steps of his predecessor in the early second century A.D., the emperor Trajan. A successful general, Trajan in A.D. 113 erected a tall, sculpted column near the Roman Forum to tell the story of his war against the Dacians (“barbarians,” as the Romans called them, from the northern frontier of the empire along the Danube River). The column reached nearly 130 feet high, with an interior spiral staircase carved out from its solid stone and, at the top, a statue of the emperor (later replaced by the statue of St. Peter that stands there today). A band of sculpted scenes illustrating preparations for the war, its battles, and much other detail spirals upward around the column, presenting a filmstrip in stone, as it were, to portray the emperor’s success. Its images provide our best evidence for what Roman soldiers and their equipment looked like. This column, the best-preserved such monument in Rome, stood at one end of the large forum that Trajan also built. This vast public space had a complex architecture, including the largest basilica (a meeting hall, especially for court cases) yet erected in Rome. The basilica’s multistoried design had an interior ceiling some 80 feet high. Rising along the hillside next to Trajan’s forum was the set of buildings known as Trajan’s Market, a labyrinth of commercial spaces built on three different street levels.

Map 8. Spoken Languages Around the Roman World

The aqueducts built to bring an endless supply of fresh water to the capital city constituted a category of architecture that greatly benefited the people of Rome. Rome’s earliest aqueduct had been built in the second century B.C., but the emperors vastly increased the public water supply by constructing channels carried atop ranks of arches that stretched for miles and miles to bring water from the surrounding hills to pour out through countless and constantly-flowing fountains scattered around the city (many still functioning today). Gravity-fed for their entire length, the aqueducts produced a steady stream of moving water. This resource provided everyone in Rome, poor as well as rich, with water safe to drink, and a flow sufficient to fill the pools of the public baths and rinse out the public toilets. The emperors also improved the supply of food for the city by continuing development of its port, located west of Rome on the coast in the town of Ostia. With some buildings preserved to more than one story, the impressive remains of ancient Ostia testify to the thriving commercial activity associated with the import-export business conducted in the port of ancient Rome.

Unlike Augustus in his outrage at the sexy poems of Ovid, his successors did not worry that scandalous literature posed a threat to the social order they worked constantly to maintain. They did, however, believe that law was crucial. Indeed, Romans prided themselves on their ability to order their society through law. As Vergil had expressed it, their mission was “to establish law and order within a framework of peace” (Aeneid 6.851–853). The principles and practices that characterized Roman law influenced most systems of law in modern Europe. Roman law’s most distinctive characteristic was the recognition of the principle of equity, which meant accomplishing what was “good and fair,” even if the letter of the law had to be ignored to do so. This principle led legal thinkers to insist, for example, that the intent of parties in a mutually agreeable deal outweighed the words of their contract, and that the burden of proof lay with the accuser rather than the accused. The emperor Trajan ruled that no one should be convicted on the grounds of suspicion alone because it was better for a guilty person to go unpunished than for an innocent person to be condemned.

The Roman desire for social order led their system of law to specify formal distinctions among people and divide them into classes defined by wealth and status. As always, the elites constituted a tiny portion of the population under the Empire. Only about one in every fifty thousand had enough money to qualify for the senatorial class, the highest status in Roman society, while about one in a thousand belonged to the equestrian class, the next rank in the social hierarchy. Different purple stripes on clothing advertised these statuses. The third-highest order consisted of local officials in provincial towns.

Those outside the social elite faced greater disadvantages than just snobbery. An old distinction that had originated in the Republic between “worthier people” and “humbler people” hardened under the Principate; by the third century A.D. it was recognized throughout the system of Roman law. The law institutionalized such distinctions because an orderly existence for everyone was thought to depend on maintaining these differences. The “better people” included senators, equestrians, curiales, and retired army veterans. Everybody else (except for slaves, who counted as property, not people) made up the vastly larger group of “humbler people.” This second group, the majority of the population, faced the gravest disadvantage of their inferior status in trials: the law imposed harsher penalties on them for the same crimes. “Humbler people” convicted of capital crimes were regularly executed by being crucified or torn apart by wild animals before a crowd of spectators. “Better people” rarely suffered the death penalty. If they were condemned, they received a quicker and more dignified execution by the sword. “Humbler people” could also be tortured in criminal investigations, even if they were citizens. Romans regarded these differences as fair on the grounds that a person’s higher status reflected a higher level of genuine merit. As the upper-class provincial governor Pliny the Younger expressed it, “nothing is less equitable than equality itself” (Letters 9.5).

Nothing mattered more to the empire’s stability and prosperity than the population continuing to reproduce itself steadily and healthily. Concern over children therefore characterized marriage. Pliny the Younger once sent the following report to the grandfather of his third wife, Calpurnia: “You will be very sad to learn that your granddaughter has suffered a miscarriage. She is a young girl and did not realize she was pregnant. As a result she was more active than she should have been and paid a high price for her lack of knowledge by falling seriously ill” (Letters 8.10). Romans saw a loss of a pregnancy not only as a family tragedy but also a loss to society.

Without antibiotics or antiseptic surgery techniques, ancient medicine could do little to promote healthy childbirth. Complications during and after delivery could easily lead to the mother’s death because doctors could not cure infections or stop internal bleeding. They did possess carefully crafted instruments for surgery and for physical examinations, but they did not know about the transmission of disease by microorganisms, and they were badly mistaken about the process of reproduction. Gynecologists erroneously recommended the days just before and after menstruation as the best time to become pregnant. As in Greek medicine, treatments were mainly limited to potions based on plants and other organic materials; some of these natural remedies were effective, but others were at best placebos, such as the drink of wild boar’s manure boiled in vinegar customarily given to chariot drivers who had been injured in crashes. Many doctors were freedmen from Greece and other provinces, usually with only informal training. People considered medical occupations to have low status, unless the practitioner served the emperor or other members of the upper class.

As in earlier times, girls often married in their early teens, giving them a longer time to bear children. Because so many children died young, families had to produce numerous offspring to keep from disappearing. The tombstone of Veturia, a soldier’s wife married at eleven, tells a typical story, here in the form of a poem singing her praises: “Here I lie, having lived for twenty-seven years. I was married to the same man for sixteen years and bore six children, five of whom died before I did” (Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum 3.3572 = Carmina Epigraphica Latina 558). Although marriages were usually arranged between spouses who hardly knew each other, husbands and wives could grow to admire and love each other in a partnership devoted to family. The butcher Lucius Aurelius Hermia erected a gravestone to his wife inscribed with this poem that she is imagined as speaking after death: “Alive, I was named Aurelia Philematium. I was chaste, modest, knowing nothing about the crowd, faithful to my husband. My husband, also a freedman, like me, I have left, alas! He was more than a parent to me. He took me to his bosom when I was seven. At forty years old I am in the power of death. He thrived through my carefully doing my duty in everything” (Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum 1.2.1221 = Inscriptiones Latinae Selectae 7472).

The emphasis on childbearing in marriage brought many health hazards to women, but to remain single and childless represented social failure for a Roman girl. Once children were born, both their mothers and servants took care of them. Women who could afford childcare routinely had their babies attended to and breast-fed by wet-nurses. Following ancient tradition, Romans continued to practice exposure (abandoning imperfect and unwanted babies), more so for infant girls than boys.

Both public and private sources did their best to support reproduction. The emperors donated financial support for children whose families were too poor to keep them. Wealthy people sometimes adopted children in their communities. One North African man gave enough money to support three hundred boys and three hundred girls each year until they grew up. The differing values placed on male and female children were evident in these welfare programs: boys often received more aid than girls. In the end, however, human intervention could barely affect this most essential process of life, leaving the empire vulnerable to devastation by epidemics. It is no wonder, then, that Romans believed their fates ultimately lay in the lap of the gods.