The Roman Empire was home to many different forms of religion, from the worship of the many gods of polytheism, to the newly important imperial cult, to the monotheism of Judaism. Almost everyone believed in the power of the divine and that it deeply affected their everyday lives, but there was a great diversity of specific religious beliefs and practices. That variety increased in the first century A.D. when Christianity began as a splinter group within Judaism in Judea, where Jews were allowed to practice their religion under Roman provincial rule. The emergence of Christianity would turn out to be the most significant long-term change for the history of the world to come from the history of ancient Rome.

Only a relatively small group of people embraced the new movement in the beginning; it was centuries before Christians became numerous. Believers in the new faith faced constant suspicion and hostility. Virtually every book of the biblical New Testament refers to the resistance that Christians encountered. Their numbers grew, if only gradually, as more people drew inspiration from stories of the charismatic career of Jesus, Christians’ belief in his role as a savior of humanity, their sense of mission, and the strong bonds of community they developed. Another source of strength was the new religion’s inclusion of women and slaves, which allowed it to draw members from the entire population.

30: Jesus is executed in Jerusalem.

64: Emperor Nero blames Christians for a huge fire in Rome.

65 (?): Paul of Tarsus is executed in Rome.

112 (?): The Roman provincial governor Pliny executes Christians in Asia Minor for refusing to sacrifice to the cult of the emperor.

Mid-second century: Roman emperors fight wars against Germanic barbarian invaders on the empire’s northern frontier in central Europe.

Late second century: The prophetesses Prisca and Maximilla preach an apocalyptic message.

193–211: Septimius Severus rules as Roman emperor and drains the imperial treasury to pay the army.

203: Perpetua is executed as a Christian martyr in Carthage.

212: Caracalla, son of Septimius Severus, extends Roman citizenship to almost everyone except slaves to try to increase government tax collections.

249 (?): Origen writes his Against Celsus to refute the philosopher Celsus’s criticisms of Christianity.

Mid-third century: The empire is in crisis from civil war, barbarian invasions, economic troubles, and epidemic disease.

260: Emperor Valerian is captured in Syria by Shapur I, the ruler of Sasanian Persia.

260–268: Emperor Gallienus stops attacks on Christians and restores church property.

The new religion was based on the life and teachings of Jesus (4 B.C.–A.D. 30). The background of Christianity lay, however, in Jewish history from long before. Harsh Roman rule in the homeland of Jesus had made the people restless and the provincial authorities anxious about rebellion. His career therefore unrolled in an unsettled environment, and his execution reflected Roman readiness to eliminate any perceived threat to peace and social order. When, after the death of Jesus, devoted followers, above all Paul of Tarsus (A.D. 5–65), preached the message that understanding the significance of Jesus was the source of salvation and spread their teachings beyond the Jewish community at the eastern end of the Mediterranean Sea to include non-Jews, Christianity took its first step into a wider, and unwelcoming, world.

For Rome’s rulers, Christianity presented a problem because it seemed to them to place individuals’ commitment to their faith above the traditional Roman value of loyalty and public service to the state. When in the third century A.D. a severe political and economic crisis struck the empire, the emperors responded in the traditional way: they looked for the people whose actions must have, the rulers believed, provoked the anger of the gods against Rome. The ones they settled on to punish for having harmed the community by angering the gods were the Christians.

The creation of Christianity had deep roots in the history of the Jews. Their harsh experiences of oppression under the rule of others raised the most difficult question about divine justice: How could a just God allow the wicked to prosper and the righteous to suffer? Nearly two hundred years before Jesus’ birth, persecution by the Seleucid king Antiochus IV (ruled 175 B.C.–164 B.C.) had provoked the Jews into a long and bloody revolt. The desperateness of this struggle pushed them to develop their version of apocalypticism (“revealing what is hidden”). According to this worldview, evil powers, divine and human, controlled the present world. This hateful regime would soon end, however, when God and his agents would reveal their plan to conquer the forces of evil by sending a deliverer, an “anointed one,” to win a great battle. A final judgment would follow, to bring eternal punishment to the wicked and eternal reward to the righteous. Apocalypticism became immensely popular, especially among the Jews living in Judea under Roman rule. Eventually, it inspired not only Jews but Christians and Muslims as well.

Apocalyptic yearnings fired the imaginations of many Jews in Judea at the time of Jesus’ birth about 4 B.C. because they were unhappy with the political situation under Roman rule and disagreed among themselves about what form Judaism should take in such troubled times. Some Jews favored subjecting themselves to their overlords, while others preached rejection of the non-Jewish world and its spiritual corruption. The Jews’ local ruler, installed by the Romans, was Herod the Great (ruled 37 B.C.–4 B.C.). His flamboyant taste for a Greek style of life, which outraged Jewish law, made him unpopular with many locals, despite his magnificent rebuilding of the holiest Jewish shrine, the great temple in Jerusalem. When a decade of unrest followed his death, Augustus punished the Jews by sending rulers directly from Rome to oversee their local leaders, and by imposing high taxes. By Jesus’ lifetime, then, his homeland had become a powder keg threatening to explode.

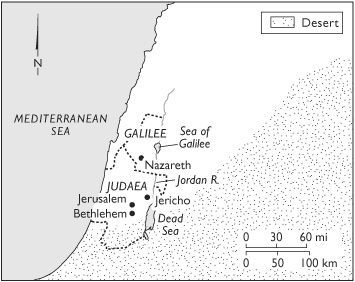

Map 9. Palestine in the Era of Jesus

Jesus began his career as a teacher and healer in his native region of Galilee during the reign of Tiberius (ruled A.D. 14–37). The New Testament Gospels, first written between about A.D. 70 and 90, offer the earliest accounts of his life. Jesus himself wrote nothing down, and others’ accounts of his words and deeds are varied and controversial. Jesus taught not by direct instruction but by telling stories and parables that challenged people to think about what he meant. Lively discussion therefore surrounded him wherever he went.

The Gospels begin the story of his public ministry with his baptism by John the Baptist, who preached a message of the need for repentance before God’s soon-to-arrive final judgment on the world. John was executed by the Jewish leader Herod Antipas, a son of Herod the Great, whom the Romans supported; Antipas feared John’s apocalyptic preaching might instigate riots.

After John’s death, Jesus continued his mission by proclaiming the imminence of God’s kingdom and the need to prepare spiritually for its coming. He accepted the designation of Messiah, but his complex apocalypticism did not preach immediate revolt against the Romans. Instead, he revealed that God’s true kingdom was not to be found on the earth but in heaven. He stressed that salvation in this kingdom was open to everyone, regardless of his or her social status or apparent sinfulness. He welcomed women and the poor, traveling around the local countryside to spread his teachings. His emphasis on God’s love for people as his children and their overriding responsibility to love one another was consistent with Jewish religious teachings, as in the interpretation of the Scriptures by the rabbi Hillel (active 30 B.C.–A.D. 9).

An educated Jew who perhaps knew Greek as well as Aramaic, the local tongue, Jesus realized that he had to reach the urban crowds to make a truly great impact. Therefore, he left the villages where he had begun his career and took his message to the region’s main towns and cities. His miraculous healings and exorcisms combined with his powerful preaching to create a sensation. His notoriety attracted the attention of the authorities, who automatically assumed that he aspired to political power. Fearing Jesus might start a Jewish revolt, the Roman regional governor Pontius Pilate (ruled A.D. 26—36) ordered his crucifixion in Jerusalem in A.D. 30, the usual punishment for threatening the peace in Roman-ruled territory.

In contrast to the fate of other suspected rebels whom the Romans executed, Jesus’s influence emphatically lived on after his punishment. His followers reported that God had miraculously raised him from the dead, and they set about convincing other Jews that he was the promised Messiah, who would soon return to judge the world and usher in God’s kingdom. At this point those who believed this had no thought of starting a new religion. They considered themselves faithful Jews and continued to follow the commandments of Jewish law.

A radical change took place with the conversion of Paul of Tarsus, a pious Jew with Roman citizenship who had formerly persecuted those who accepted Jesus as the Messiah. After a religious vision that he interpreted as a direct revelation from Jesus, Paul became a believer, or a Christian (follower of Christ), as members of the new movement came to be known. Paul made it his mission to tell as many people as possible that accepting Jesus’s death as the ultimate sacrifice for the sins of humanity was the only way to be righteous in the eyes of God. Those who accepted Jesus as divine and followed his teachings could expect to attain salvation in the world to come. Paul’s teachings and his strenuous efforts to spread his ideas among people outside Judea led to the creation of Christianity as a new religion.

Although Paul stressed the necessity of ethical behavior, especially avoiding sexual immorality and not worshiping traditional Greco-Roman gods, he also taught that there was no need to keep all the provisions of Jewish law. Seeking to bring Christianity outside the Jewish community, he directed his efforts to the non-Jews of Syria, Asia Minor, and Greece. To make conversion easier, he did not require the males who entered the movement to undergo the Jewish initiation rite of circumcision. This tenet, along with his teachings that his congregations did not have to observe Jewish dietary restrictions or festivals, led to tensions with the followers of Jesus living in Jerusalem, who still believed Christians had to follow Jewish law. Although Paul preached that Christians should follow traditional social rules in everyday life in the current world, including the distinction between free people and slaves, the controversy generated by his appearances in many cities in the eastern provinces of the empire led Roman authorities to arrest him as a criminal troublemaker and execute him about A.D. 65.

Paul’s mission was only one part of the turmoil afflicting the Jewish community in this period. Hatred of Roman rule finally provoked the Jews to revolt in 66, with disastrous results. After defeating the rebels in A.D. 70 in a bloody siege that saw the Jewish Temple destroyed by fire, Titus sold most of the city’s population into slavery. Without a temple to serve as the center of their ancestral rituals, Jews had to reinvent the practices of their religion. In the aftermath of this catastrophe, the distancing of Christianity from Judaism that Paul had begun gained momentum, giving birth to a separate religion. His impact on the movement can be gauged by the number of his letters—thirteen—that were included in the collection of twenty-seven Christian writings that became the New Testament. Followers of Jesus came to regard these writings as having equal authority with the Jewish Bible, which they now called the Old Testament. Since teachers like Paul preached mainly in the cities, where the crowds were, congregations of Christians began to spring up among non-Jewish, urban, middle-class men and women, with a few richer and poorer members. Women as well as men could hold offices in these congregations. Indeed, the first head of a congregation attested in the New Testament was a woman.

Christianity had to overcome serious challenges to become a new religion separate from Judaism. The emperors found Christians baffling and irritating. Since, unlike Jews, Christians followed a novel faith rather than a traditional religion handed down from their ancestors, they enjoyed no special treatment under Roman law. The Romans traditionally respected different customs and beliefs if they were ancient, but they were deeply suspicious of any new creed. Romans also looked down on Christians because Jesus, their divine savior, had been crucified as a criminal by the government. Christians’ worship rituals also aroused hostility because they led to accusations of cannibalism and sexual promiscuity arising from Christians’ ritual of eating the body and drinking the blood of Jesus during their central rite, which they called the Love Feast. In short, they seemed a dangerous threat to traditional social order. Roman officials, suspecting Christians of being politically subversive, could prosecute them for treason, especially for refusing to participate in the imperial cult.

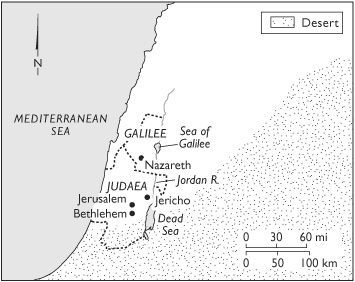

Figure 22. A mosaic portrays Christ riding in a chariot through the sky with light rays extending from his head, in the style of traditional depictions of the sun god. Early Christian art frequently took its models from the image traditions of Greek and Roman religion. Scala/Art Resource, NY.

It made sense to Roman officials, therefore, to blame Christians for public disasters. When a large part of Rome burned in A.D. 64, Nero punished them for arson. As Tacitus reports (Annals 15.44), Nero had Christians “covered with the skins of wild animals and mauled to death by dogs, or fastened to crosses and set on fire to provide light at night.” The harshness of this punishment ironically earned the Christians some sympathy from Rome’s population. After this persecution, the government acted against Christians only intermittently. No law specifically forbade their religion, but they made easy prey for officials, who could punish them in the name of maintaining public order. The action of Pliny as a provincial governor in Asia Minor illustrated their predicament. About A.D. 112 he asked some people accused of practicing this new religion if they were indeed Christians, urging those who admitted it to reconsider. Those who denied it, as well as those who stated they no longer believed, he freed after they sacrificed to the imperial cult and cursed Christ. He executed those who persisted in their faith.

From the official point of view, Christians had no right to retain their religion if it created disturbances. As a letter from Emperor Trajan to Pliny made clear, however, the emperors had no policy of tracking them down. Christians concerned the government only when authorities noticed their refusal to participate in official sacrifices or non-Christians complained about them. Ordinary Romans felt hostile toward Christians mostly because they feared that tolerating them would bring down upon everyone the wrath of the gods of traditional Roman religion. Christians’ refusal to participate in the imperial cult caused the most concern. Because they denied the existence of the old gods and the divine associations of the emperor, they seemed sure to provoke the gods to punish the world with natural catastrophes. Tertullian (A.D. 160–220), a Christian scholar from North Africa, described this thinking (Apology 40): “If the Tiber River overflows, or if the Nile fails to flood; if a drought or an earthquake or a famine or a plague hits, then everyone immediately shouts, ‘To the lions with the Christians!’”

In response to official hostility, intellectuals such as Tertullian and Justin (A.D. 100–165) defended their cause by arguing that Romans had nothing to fear from Christians. Far from spreading immorality and subversion, these writers insisted, the Christian religion taught an elevated moral code and respect for authority. It was not a foreign superstition, but rather the true philosophy that combined the best features of Judaism and Greek thought and was thus a fitting religion for their diverse world. As Tertullian pointed out (Apology 30), though Christians could not worship the emperors, they did “pray to the true God for their safety. We pray for a fortunate life for them, a secure rule, safety for their families, a courageous army, a loyal Senate, a virtuous people, a world of peace.”

Official hostility to Christians had the opposite effect to its intention of suppressing the new religion; as Tertullian remarked (Apology 50), “the blood of the martyrs is the seed of the Church.” Some Christians regarded public trials and executions as an opportunity to become witnesses (“martyrs” in Greek) to their faith. Their firm conviction that their deaths would take them directly to paradise allowed them to face excruciating tortures with courage; some even tried for martyrdom. Ignatius (A.D. 35–107), bishop of Antioch, begged the Rome congregation, which was becoming the most prominent one, not to ask the emperor to show him mercy after his arrest (Epistle to the Romans 4): “Let me be food for the wild animals (in the arena) through whom I can reach God,” he pleaded. “I am God’s wheat, to be ground up by the teeth of beasts so that I may be found pure bread of Christ.”

Women as well as men could show their determination as martyrs. In A.D. 203, Vibia Perpetua, wealthy and twenty-two years old, nursed her infant in a Carthage jail while awaiting execution; she had received the death sentence for refusing to sacrifice an animal to the gods for the emperor’s health and safety. One morning the jailer dragged her off to the city’s main square, where a crowd had gathered. Perpetua described in her diary what happened when the local governor made a last, public attempt to get her to save her life:

My father came carrying my son, crying “Perform the sacrifice; take pity on your baby!” Then the governor said, “Think of your old father; show pity for your little child! Offer the sacrifice for the welfare of the imperial family.” “I refuse,” I answered. “Are you a Christian?” asked the governor. “Yes.” When my father would not stop trying to change my mind, the governor ordered him flung to the earth and whipped with a rod. I felt sorry for my father; it seemed they were beating me. I pitied his pathetic old age (The Passion of Saints Perpetua and Felicity 6).

Perpetua’s punishment was then carried out: gored by a wild bull and stabbed by a gladiator, she died professing her faith. She was later recognized as a saint. Stories such as Perpetua’s proclaimed the martyrs’ courage to inspire other Christians to stand up to hostility from non-Christians. They also helped to attract new members and to shape the identity of this new religion as a faith that gave its believers the spiritual power to endure great suffering.

Christians in the first century A.D. expected Jesus to return to pass final judgment on the world during their lifetimes. When this hope was not met, by the second century they began transforming their religion from an apocalyptic Jewish sect expecting the immediate end of the world into one that could survive over the long term. To do this, they had to create organizations with leaders tasked to build connections between congregations, work for order and unity among often-fractious groups, and reconcile diverse beliefs about their new faith, including disagreements about the role of women in the congregations.

Order and unity were hard for Christians to achieve because they constantly and fiercely disagreed about what they should believe and how they should live. The bitterest arguments came over how they should follow God’s command to imitate his love for them by loving each other with tenderness and compassion. Some insisted that it was necessary to withdraw from the everyday world to escape its evil. Others believed they could strive to live by Christ’s teachings while retaining their jobs and ordinary lives. Many Christians questioned whether they could serve as soldiers without betraying their religious beliefs because the army regularly participated in its patron’s cult. This dilemma raised the further issue of whether Christians could remain loyal subjects of the emperor. Controversy over such issues raged in the many congregations that had arisen by the second century around the Mediterranean, from Gaul to Africa to Mesopotamia.

The appointment of bishops as a hierarchy of leaders with authority to define doctrine and conduct was the most important institutional development to deal with this disunity. This hierarchy was intended to combat the splintering effect of the differing and competing versions of the new religion and to promote “communion” among congregations, an important value of early Christianity. Bishops had the power to define what was orthodoxy (true doctrine as determined by councils of themselves) and what was heresy (from the Greek word meaning “private choice”). Most importantly, they decided who could participate in worship, especially the Eucharist, or Lord’s Supper, which many Christians regarded as necessary for achieving eternal life. Exclusion meant losing salvation. For all practical purposes, the meetings of the bishops of different cities constituted the final authority in the church’s organization. This loose organization became the early Catholic Church.

Christians could not agree on the role women should play in the church and its hierarchy. In the earliest congregations, women held leadership positions, an innovation that contributed to Roman officials’ suspicion of Christianity. When bishops began to be chosen, however, women were usually relegated to inferior positions. This demotion reflected Paul’s view that in Christianity women should be subordinate to men; he also reaffirmed the view of his times that slaves should be subordinate to their masters.

Some congregations took a long time to accept this demotion of female believers; women still commanded positions of authority in some groups in the second and third centuries A.D. The late second-century prophetesses Prisca and Maximilla, for example, proclaimed the apocalyptic message of Montanus that the Heavenly Jerusalem would soon descend in Asia Minor. Second-century Christians could also find inspiration for women as leaders in written accounts of devout believers such as Thecla. As a young woman, she canceled her engagement to a prominent noble in order to join Paul in preaching and founding churches. Thecla’s courage overruled her mother’s sadness at her refusal to marry: “My daughter, like a spider bound at the window by that man’s words, is controlled by a new desire and a terrible passion” (The Acts of Paul and Thecla 9). Even when leadership posts were closed off to them, many women still chose a life of celibacy to serve the church. Their commitment to chastity as proof of their devotion to Christ gave these women the power to control their own bodies by removing their sexuality from the control of men. It also bestowed social status upon them, as women with a special closeness to God. By rejecting the traditional roles of wife and mother in favor of spiritual celebrity, celibate Christian women achieved a measure of independence and authority generally denied to them in the outside world.

Diverse ideas and rituals also characterized the old polytheism of Greco-Roman religion, just as in the new faith of Christianity. Even two centuries after Jesus’s death the overwhelming majority of religious people were still polytheists, worshiping numerous different gods and goddesses. What polytheists did agree on was that the empire’s success and prosperity demonstrated that the old gods favored and protected their community and that the imperial cult added to their safety.

The religious beliefs and rituals of traditional religion in ancient Rome were meant to offer worship to all the divinities that could affect human life and thereby win divine favor for the worshipers and their community. The deities ranged from the central gods of the state cults, such as Jupiter and Minerva, to local spirits thought to inhabit forests, rivers, and springs. In the third century A.D., the emperors imitated the ancient pharaohs of Egypt by officially introducing worship of the sun as the supreme deity of the empire. Several popular new religious cults also emerged as the empire’s diverse regions mingled their traditions. The Iranian god Mithras developed a large following among merchants and soldiers as the god of the morning light, a superhuman hero requiring ethical conduct and truthful dealings from his followers. Since Mithraism excluded women, this restriction put it at a disadvantage in expanding its membership.

The cult of the Egyptian goddess Isis best reveals how traditional religion could provide believers with a religious experience that aroused strong personal emotions and demanded a moral way of life. The worship of Isis had already attracted Romans by the time of Augustus. He tried to suppress it because it was Cleopatra’s religion, but Isis’s widely known reputation as a kind and compassionate goddess who cared for the suffering of each of her followers made her cult too popular to crush. Her image was that of a loving mother, and in art she was often shown nursing her son. The Egyptians even said that it was her tears for her starving people that caused the Nile to flood every year and bring good harvests to the land. A central doctrine of the cult of Isis concerned the death and resurrection of her husband, Osiris. Isis promised her followers a similar hope for life after death for themselves. Her cult was open to both men and women. A preserved wall painting found at Pompeii in Italy shows people of both dark- and light-skinned races officiating at her rituals, reflecting the diversity of the population of Egypt where her worship originated.

Isis required her believers to behave morally. Inscriptions put up for all to read expressed her high standards by referring to her own civilizing accomplishments: “I put down the rule of tyrants; I put an end to murders; I forced women to be loved by men; I caused what is right to be mightier than gold and silver” (Burstein, no. 112). The hero of Apuleius’s novel, whom Isis rescued from a life of pain, humiliation, and immorality, expressed his intense joy after having been spiritually reborn by the goddess (The Golden Ass 11.25): “O holy and eternal guardian of the human race, who always cherishes mortals and blesses them, you care for the troubles of miserable humans with a sweet mother’s love. Neither day nor night, nor any moment of time, ever passes by without your blessings.” Other traditional cults also required their worshipers to lead morally upright lives. Inscriptions from villages in Asia Minor record ordinary people’s confessions to sins, such as sexual transgressions, for which their local god had imposed harsh penance on them. In this way, their polytheist religion guided their moral lives.

Religion was not the exclusive guide to life in the Roman Empire. Many people believed that philosophic principles also helped them to understand the nature of human existence and how best to live. Stoicism, derived from the teachings of the Greek philosopher Zeno (335 B.C.–263 B.C.), was the most popular philosophy among Romans. Stoic values emphasized self-discipline above all else, and their code of personal ethics left no room for out-of-control conduct. As the first-century A.D. author Seneca put it in a moral essay on controlling one’s rage, “It is easier to prevent harmful emotions from entering the soul than it is to control them once they have entered” (On Anger 1.7.2). Stoicism taught that a single creative force incorporating reason, nature, and divinity guided the universe. Humans shared in the essence of this universal force and found happiness and patience by living in accordance with it. The emperor Marcus Aurelius in his Meditations, written while he was on military campaign on the cold northern frontier of the empire, bluntly expressed the Stoic belief that people exist for each other: “Either make others better, or just put up with them,” he insisted (Meditations 8.59). Furthermore, he repeatedly stressed, people owed obligations to society as part of the natural order; the conduct of every moral person needed to reflect this truth. The Stoic philosopher Musonius Rufus insisted that this principle was just as true for women as for men, and he supported philosophic education for both genders.

Figure 23. This Roman statue depicts Isis, the Egyptian goddess whose cult became extremely popular in the empire; she is holding objects used in her worship. Worshipers prized her as a source of salvation and protection—a kind and caring mother with divine powers. Marie-Lan Nguyen/Wikimedia Commons.

Other systems of philosophy, especially those rooted in the thought of Plato (429 B.C.–347 B.C.), challenged Christian intellectuals to defend their new faith. About A.D. 176, for example, Celsus published a wide-ranging attack on Christianity reflecting his ideas as a follower of Plato. His essay On the True Doctrine revealed what educated non-Christians knew about the new faith and their varied reasons for rejecting it. As his arguments show, they had difficulty understanding the basic ideas of Christian belief in this period, to say nothing of the diversity of competing “orthodox” and “heretical” versions. In his criticism of Christianity, Celsus paid no attention to accusations of evil and immoral conduct by Christians, although this type of slander had become common. Instead, he concentrated on philosophical arguments, such as the Platonic insistence on the immateriality of the soul as contrasted to the Christian belief in bodily resurrection on the Day of Judgment. In short, Celsus accused Christians of intellectual deficiency rather than immorality.

Celsus’s work achieved great notoriety as a formidable challenge to Christianity on intellectual and philosophical grounds. So strong and enduring was its influence that even seventy years later a well-known teacher and philosopher, Origen (A.D. 185–255), composed a work entitled Against Celsus (Contra Celsum) to refute Celsus’s arguments. Origen insisted that Christianity was both true and superior to traditional philosophy as a guide to correct living.

At about the same time, however, traditional religious belief achieved its most intellectual formulation in the works of Plotinus (A.D. 205–270). Plotinus’s spiritual philosophy, called Neoplatonism because it developed new doctrines based on Plato’s philosophy, influenced many educated Christians as well as traditional believers. The religious doctrines of Neo-platonism focused on the human longing to return to the abstract universal Good from which human existence was derived. By turning away from the life of the body through the intellectual pursuit of philosophy, individual souls could ascend to the level of the universal soul. In this way, individuals could become unified with the whole that expressed the true meaning of existence. This mystical union with what the Christians would call God could be achieved only through strenuous self-discipline in personal morality as well as in intellectual life. Neoplatonism’s stress on spiritual purity gave it a powerful appeal.

Stoicism, the worship of Isis, Neoplatonism—all these manifestations of traditional philosophy and religion paralleled Christianity in providing guidance, comfort, and hope to people through good times or bad. By the third century A.D., then, thoughtful people had various options of what to believe in to help them survive the harshness of ancient life. The seriousness of the competition for adherents among these different belief systems is reflected in the growing emphasis on the complex history of religion, especially Christianity, found in the sources that have survived until today.

Life became much harsher for many Romans across the empire in the third century A.D. Some regions suffered less than others, but multiple disasters combined to create a crisis for government and society. The invasions that outsiders had long been conducting on the northern and eastern frontiers had forced the emperors to expand the army, but the increased need for military pay and supplies strained imperial finances because, with no more successful conquests, the army had become a source of negative instead of positive cash flow to the treasury. The nonmilitary economy did not expand sufficiently to provide revenues to make up the difference. In short, the emperors’ need for revenue had grown faster than the empire’s tax base. This discrepancy fueled a crisis in national defense because the emperors’ desperate schemes to raise money to pay and equip the troops damaged the economy and eroded public confidence in the empire’s security. The unrest that resulted encouraged ambitious generals to repeat the crimes that had destroyed the Republic, leading personal armies to seize power. Civil war once again ravaged Rome, lasting for decades in the middle of the century and destabilizing the Principate system of government.

Emperors concerned with national defense had been leading campaigns to repel invaders since the reign of Domitian in the first century A.D. The most aggressive attackers were the loosely organized Germanic bands that often crossed the Danube and Rhine rivers from the north to raid the provinces there. These invaders had begun to mount damaging attacks during the reign of Antoninus Pius (A.D. 138–161) and then greatly escalated the pressure in the rule of Marcus Aurelius (A.D. 161–180). Constant fighting against the Roman army allowed these originally disorganized warrior bands to develop greater military cohesiveness. This change made them much more effective and laid the basis for the enormous military challenges that they would later present to the Roman Empire in the fourth and fifth centuries.

Respecting the great fighting spirit of Germanic warriors, the emperors began hiring them as auxiliary soldiers for the Roman army and settling them on the frontiers as buffers against other invaders. This recruitment of foreign soldiers became a key resource in national defense; it had the unintended consequence of allowing the Germans to experience the comparative comfort and prosperity of Roman life on a daily basis. This development over time increased the tendency for these “barbarians” to want to stay in the empire’s territory permanently. This tendency in turn put in motion a long-term pattern of change that was eventually going to alter the shape and structure of the empire forever, even foreshadowing the territorial outlines of the nation states of modern Europe.

The emperors tried to meet the increasing threat of invasion by expanding the number of regular and auxiliary soldiers. By around A.D. 200, the army had 100,000 more troops than under Augustus, enrolling perhaps as many as 350,000 to 400,000 men. It was crucial to guarantee regular pay to keep these men content because their career was rugged. Training constantly, soldiers had to be fit enough to carry forty-pound packs up to twenty miles in five hours, swimming rivers in their way. Since on the march they built a fortified camp every night, they carried all the makings of a wooden-walled city with them everywhere they went. As one writer reported after seeing Roman soldiers in action, “infantrymen were little different from loaded pack mules” (Josephus, The Jewish War 3.95). Huge quantities of supplies were required to support the army. At one temporary fort in a frontier area, archaeologists found a supply of a million iron nails—ten tons’ worth. The same encampment required seventeen miles of planks and logs for its buildings and fortifications. To outfit a single legion of five to six thousand men with tents required fifty-four thousand calves’ hides.

To make matters worse, inflation had driven up prices. A principal cause of inflation under the early Empire may have been, ironically, the long period of “Roman Peace” that had promoted increased demand for the economy’s relatively static production of goods and services. Over time, some emperors responded to inflated prices by debasing the most important form of official currency—the silver coins issued under the ruler’s name. Debasement of the coinage involved putting less silver in each coin without reducing its face value to reflect the lower quantity of precious metal and therefore the lower intrinsic value of the money. With this technique, emperors hoped to create more cash from the same amount of precious metal. This attempt to cut government costs for purchasing goods and services soon became a dismal failure. Merchants, who were not fooled, simply raised prices to make up for the loss in value from the debased currency, leading to hyperinflation of prices. By the end of the second century A.D., these pressures had imposed a permanent shortfall in the imperial balance sheet. Still, the soldiers demanded that their patrons, the emperors, pay them well. The stage was set for a full-blown financial crisis in the imperial government.

Emperor Septimius Severus (A.D. 145–211) and his sons Caracalla and Geta set the catastrophe into final motion. These emperors from the Severan family fatally drained the treasury to satisfy the army. In addition, the sons’ murderous rivalry with each other and reckless spending further destabilized the empire. An experienced military man who came from Punic ancestors in the large North African city of Lepcis Magna (in what is today Libya), Severus seized imperial power in A.D. 193 as a result of a crisis in Rome following the murder of Marcus Aurelius’s son Commodus, and defeated rival claimants for power in several years of civil war. To try to win money for his army and glory for his family, Severus vigorously pursued the traditional imperial dream of foreign conquest by launching campaigns beyond the eastern and western ends of the empire in Mesopotamia and Scotland respectively. Unfortunately, these expeditions failed to bring in enough profits to fix the imperial budget deficit.

The soldiers were desperate because inflation had diminished the value of their wages to virtually nothing after the costs of basic supplies and clothing were deducted from their pay, according to long-standing army regulations. The troops therefore routinely expected the emperors as their patrons to provide them with regular bonuses. Severus spent large sums to provide this money, and he also decided to improve their condition over the long term by raising their regular rate of pay by a third. The expanded size of the army made this raise more expensive than the treasury could handle and further increased inflation. The dire financial consequences of his military policy concerned Severus not at all. His deathbed advice to his sons in A.D. 211 was to “stay on good terms with each other, make the soldiers rich, and pay no attention to everyone else” (Cassius Dio, Roman History 77.15).

Severus’s sons followed this advice only on the last two points. Caracalla (A.D. 188–217) secured sole rule for himself by murdering his brother Geta. Caracalla’s violent and profligate reign definitively ended the peace and prosperity of the empire’s Golden Age. He increased the soldiers’ pay by another 40 to 50 percent and also spent gigantic sums on grandiose building projects, including the largest public baths Rome had ever seen, covering blocks and blocks of the city. Caracalla’s extravagant spending put unbearable pressure on the local provincial officials responsible for collecting taxes and on the citizens whom they pressed to pay ever-greater amounts. In short, he wrecked the imperial budget and paved the way for ruinous inflation in the coming decades.

In A.D. 212 Caracalla took his most famous step to try to resolve the budget crisis: he granted Roman citizenship to almost every man and woman in the empire except slaves. Because only citizens paid inheritance taxes and fees for freeing slaves, an increase in citizens meant an increase in revenues, most of which was earmarked for the army. But too much was never enough for Caracalla. Those close to him whispered that he was insane. Once when his mother upbraided him for his excesses he replied, “Never mind,” as he drew his sword, “we shall not run out of money as long as I have this” (Cassius Dio, Roman History 78.10). In 217 the commander of Caracalla’s bodyguards murdered him to make himself emperor.

A combination of human and natural disasters following the rule of the Severan emperors brought on the climax of the third-century crisis in the Roman Empire. First, political instability accompanied the imperial government’s accelerating financial weakness. For almost seventy years in the mid-third century A.D., a parade of emperors and pretenders fought over power. Nearly thirty men held or claimed the throne, often several at a time, during these decades of near-anarchy. Their only qualification was their ability to command troops and to reward them for loyalty to themselves instead of the state.

The nearly constant civil wars of the mid-third century exacted a tremendous toll on the population and the economy. Insecurity combined with hyperinflation to make life miserable in much of the empire. Agriculture withered as farmers found it impossible to keep up normal production in wartime, when battling armies damaged their crops searching for food. City council members faced constantly escalating demands for tax revenues from the swiftly changing emperors. The constant financial pressure destroyed local elites’ willingness to support their communities.

Foreign enemies took advantage of this period of crisis to attack, especially from the east and the north. Roman fortunes hit bottom when Shapur I, king of the Sasanian Empire of Persia, captured the emperor Valerian (ruled A.D. 253–260) in Syria in A.D. 260. Even the tough and experienced emperor Aurelian (ruled A.D. 270–275) could manage only defensive operations, such as recovering Egypt and Asia Minor from Zenobia, the warrior queen of Palmyra in Syria. Aurelian also encircled Rome with a massive wall more than eleven miles long to ward off surprise attacks from Germanic tribes, who were already smashing their way into Italy from the north. The Aurelian Wall snaked its way among Rome’s hills, at one point incorporating one of Rome’s most idiosyncratic monuments, the marble-faced pyramid that the wealthy Roman official C. Cestius built to be his tomb at the end of the first century B.C. Sections of the Aurelianic wall and its towers and gates can still be seen looming high above the streets at various places in modern Rome, such as at the Porta San Sebastiano opening onto the Appian Way.

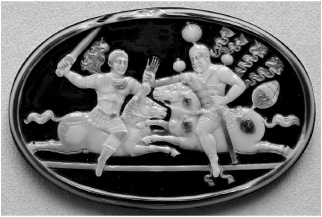

Figure 24. A Persian cameo shows Shapur I, a Sasanian king, accepting the surrender of the Roman emperor Valerian in A.D. 260. The Sasanian Empire rivaled those of Rome and of China as the world’s most powerful of that era. Marie-Lan Nguyen/Wikimedia Commons.

Natural disasters compounded the crisis when devastating earthquakes and virulent epidemics struck the Mediterranean region in the middle of the century. The population declined significantly as food supplies became less dependable, civil war killed soldiers and civilians alike, and infection flared over large regions. The loss of population meant fewer soldiers for the army, whose efficiency as a defense force and internal provincial security corps had already deteriorated seriously from political and financial chaos. More frontier areas of the empire therefore became vulnerable to raids, while roving bands of robbers also became more and more common inside the borders as economic conditions worsened. This deadly mix of troubles brought the empire to the brink of collapse. By this time, Romans once again desperately needed to refocus their values and transform their political system to keep their government and society from disintegrating.

Map 10. Significant Populations of Christians, Late Third Century A.D.

Believers in traditional Roman religion explained these horrible times in the traditional way: the state gods were angry. But why? One obvious possibility seemed to be the growing presence of Christians, who denied the existence of Rome’s gods and refused to participate in their worship. Therefore, the emperor Decius (ruled A.D. 249–251) conducted violent and, for the first time, systematically organized persecutions to eliminate this contaminated group and restore the goodwill of the gods. Decius ordered all inhabitants of the empire to prove their loyalty to the welfare of the state by participating in a sacrifice to its gods. Christians who refused were executed. Supporting the new emperor’s claim to be the defender of Rome’s protective cults and the freedom that polytheists believed that their ancestral rituals secured for Rome, the citizens of an Italian town in a public inscription praised Decius as “the Restorer of the Sacred Rites and of Liberty” (Babcock 1962). On the other side of the persecution, Cyprian, a convert from paganism who had become bishop of Carthage, urged Christians to be ready for martyrdom at the hands of the Antichrist (Letters 55).

These widespread persecutions did not stop the civil war, economic failure, and diseases that had precipitated the empire’s protracted crisis. The emperor Gallienus (ruled A.D. 260–268) acted to restore religious peace to the empire by stopping the attacks on Christians and allowing bishops to recover church property that had been confiscated. This policy reduced overt tensions between Christians and the imperial government for the rest of the century. By the 280s A.D., however, no one could deny that the empire was tottering on the edge of the abyss financially and politically.