Remarkably, the empire was to be dragged back to safety in the same way it had begun: by creating a new form of authoritarian leadership, this time to replace the Principate, which had replaced the Republic. When Diocletian became emperor (ruled A.D. 284–305), he rescued the empire from its crisis by replacing the Principate with a more openly autocratic system of rule. As Roman emperor, Diocletian used his exceptional talent for leadership to reestablish centralized political and military authority. His administrative and financial reforms changed the shape and finances of the empire, while his persecution of Christians failed to prevent the new faith from becoming the official religion of the Roman Empire in the fourth century A.D., the time in which Roman history reaches the chronological period that modern historians often refer to as the “later Empire.”

Emperor Constantine’s conversion to Christianity in the early fourth century A.D. is understandably seen as a turning point in the history of Rome. He set the empire on a gradual path to Christianization, meaning the formal recognition of the new religion both as the official religion of the state and of the majority of the population. The process of Christianizing the Roman Empire was slow and tense, as Constantine’s policy of religious toleration did not change people’s minds about how wrong—and therefore dangerous—the people were who worshiped differently from themselves. Christians thought that traditional believers were idolaters and atheists; traditional believers feared Christians threatened the goodwill of the gods of the official state cults that they saw as protecting the empire.

284–306: Diocletian rules as Roman emperor and establishes the Dominate, ending the political crisis of the third century.

285: Antony becomes a Christian monk living alone in the Egyptian desert.

301: Diocletian imposes price and wage controls in a failed attempt to control inflation.

303: Diocletian begins the Great Persecution of Christians to try to restore the “peace of the gods.”

306–337: Constantine rules as Roman emperor.

312: Constantine wins the battle of the Milvian Bridge in Rome and proclaims himself a Christian.

313: Constantine announces a policy of religious toleration.

321: Constantine makes Sunday the Lord’s Day.

324–330: Constantine builds a new capital, Constantinople (today Istanbul), on the site of ancient Byzantium.

325: Constantine holds the Council of Nicea to try to end disputes over Christian doctrine.

349: St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome is completed.

361–363: Emperor Julian tries (and fails) to reestablish traditional polytheism as the state’s leading religion.

382: The Altar of Victory is removed from the Senate House in Rome.

386: Augustine converts to Christianity.

391: Emperor Theodosius makes Christianity the official religion by successfully banning pagan sacrifices.

415: The pagan philosopher Hypatia is murdered by Christians in Alexandria.

No one could have predicted Diocletian’s spectacular imperial career: he originated as an uneducated military man from the rough region of Dalmatia in the Balkans. His courage and intelligence propelled him through the ranks until with the backing of the army he was recognized as the emperor in A.D. 284. He ended the third-century A.D. crisis by imposing the most autocratic system of rule the Roman world had yet seen.

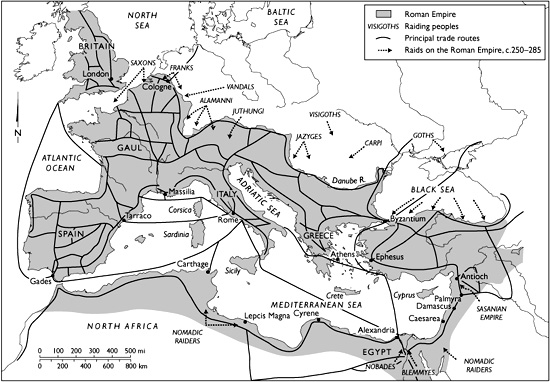

Map 11. The Roman Empire in the Third-Century A.D. Crisis

Relying on the military’s support, he had himself formally recognized as dominus (“Master”—the term slaves called their owners) instead of “First Man.” For this reason, historians refer to the system of Roman imperial government from Diocletian onward as the Dominate. The Dominate’s system of blatant autocracy—rulers openly claiming and exercising absolute power—eliminated any pretense of shared authority between the emperor and the Roman elite. Senators, consuls, and other traces of traditions of the Republic continued to exist—including the name “Republic” for the government—but these survivals from long ago were kept on only to give a façade of traditional political legitimacy to the new autocratic system. The emperors of the Dominate would increasingly choose their imperial officials from the lower ranks of society based on their competence and loyalty to the ruler, instead of automatically taking high-ranking administrators from the upper class.

As “Masters” the emperors developed new ways to display their supremacy. Abandoning the precedent set by Augustus of wearing plain, everyday clothes, the rulers in the Dominate dressed in jeweled robes, wore dazzling crowns, and surrounded themselves with courtiers and ceremony. To show the difference between the “Master” and ordinary people, a series of veils separated the palace’s waiting rooms from the inner space where the ruler held audiences. Officials marked their rank in the fiercely hierarchical imperial administration with grandiose titles such as “Most Perfect” and showed off their status with special shoes and belts. In its style and propaganda, the Dominate’s imperial court more closely resembled that of the Great King of Persia a thousand years earlier and that of the contemporary Sasanian kingdom in Persia than that of the first Roman emperor. Following ancient Persian custom, people seeking favors from the “Master” had to throw themselves at his feet like slaves and kiss the gem-encrusted hem of his golden robe. The architecture of the Dominate also reflected the image of its rulers as all-powerful autocrats. When Diocletian built a public bath in Rome, it dwarfed its rivals with soaring vaults and domes covering a space over three thousand feet long on each side.

The Dominate also developed a theological framework for legitimizing its rule. Religious language was used to mark the emperor’s special status above everybody else. The title et deus (“and God”), for example, could be added to “Master” as a mark of supreme honor. Diocletian also adopted the title Jovius, proclaiming himself descended from Jupiter (Jove), the chief Roman god. When two hundred years earlier the Flavian emperor Domitian had tried to call himself “Master and God,” this display of pride had helped turn opinion against him. Now, these titles became usual, expressing the sense of complete respect and awe that emperors now expected from their subjects and demonstrating that imperial government on earth replicated the hierarchy of the gods.

The Dominate’s emperors asserted their autocracy most aggressively in law and punishments for crime. Their word alone made law; the Assemblies of the Republic were no longer operating as sources of legislation. Relying on a personal staff that isolated them from the outside world, the emperors rarely sought advice from the elite, as earlier rulers had traditionally done. Moreover, their concern to maintain order convinced them to increase the severity of punishment for crimes to brutal levels. Thus Emperor Constantine in A.D. 331 ordered officials to “stop their greedy hands” or be punished by having their hands cut off by the sword (Theodosian Code 1.16.7). Serious criminals could be tied in a leather sack with snakes and drowned in a river. The guardians of a young girl who had allowed a lover to seduce her were punished by having molten lead poured into their mouths. Punishments grew especially harsh for the large segment of the population legally designated as “humbler people,” but the “better people” generally escaped harsh treatment. In this way, the Dominate’s autocracy strengthened the divisions between the poorer and the richer sections of the population.

Despite Diocletian’s success in making himself into an autocrat, he concluded that the empire was too large to administer and defend from a single center. He therefore subdivided the rule of the empire to try to hold it together. In a daring innovation, he effectively split imperial territory in two by creating one administrative region in the west and another in the east. This essentially created a Western Roman Empire and an Eastern Roman Empire, though this division was not yet formally recognized. He then subdivided these regions in two, appointing four “partners” in rule to govern cooperatively, each controlling a separate district, capital city, and military forces. To prevent disunity, the most senior partner—in this case Diocletian—served as emperor and was supposed to receive the loyalty of the other three co-emperors. This tetrarchy (“rule of four”) was meant to keep imperial government from being isolated in Rome, distant from the empire’s elongated frontiers where trouble often lurked, and to prevent civil war by identifying successors in an orderly fashion.

The creation of the four regions ended Rome’s thousand years as the Romans’ capital. Diocletian did not even visit the ancient city until nearly twenty years after becoming emperor. He chose the regions’ new capitals for their utility as military command posts: Milan in northern Italy, Sirmium near the Danube River border, Trier near the Rhine River border, and Nicomedia in Asia Minor. Italy became just another section of the empire, on an equal footing with the other provinces and subject to the same taxation system, except for Rome itself; this exemption was the last trace of the city’s traditional primacy.

Figure 25. This sculpture shows the tetrarchs whom Emperor Diocletian established to govern the empire. The similar size and style of the depictions of the co-emperors symbolize the close ties and harmony that Diocletian hoped his colleagues would display. Giovanni Dall’Orto/Wikimedia Commons.

Diocletian’s rescue of the empire called for vast revenues, which the third century’s hyperinflation had made hard to find. The biggest expense stemmed from expanding the army by 25 per cent. He used his power as sole lawmaker to dictate two reforms meant to improve the financial situation: controlling wages and prices and imposing a new taxation system.

The restrictions on wages and prices resulted from Diocletian’s blaming private businesspeople instead of government action—the massive debasement of coinage—for the unheard-of level of inflation in many regions. Inflated prices caused people to hoard whatever they could buy, which only drove up prices even higher. “Hurry, spend all my money you have; buy me any kinds of goods at whatever prices they are available,” wrote one official to his servant when he discovered another devaluation was scheduled (Roberts and Turner vol. 4, pp. 92–94, papyrus no. 607). In A.D. 301, Diocletian tried to curb inflation by imposing an elaborate system of wage and price controls in the worst hit areas; he called this preventing “injustice in commerce.” His Edict on Maximum Prices, which explicitly blamed high prices on what the emperor regarded as the unlimited greed of profiteers in supplying food, transportation, and many other things, banned hoarding and set ceilings on the amounts that could legally be charged or paid for about a thousand goods and services (Frank vol. 5, pp. 305–421). The edict soon became ineffective, however, because merchants and workers refused to cooperate, and government officials proved unable to force them to follow the new rules, despite the threat of death or exile as the penalty for violations.

Taxation had to be reformed because the government’s inability to control inflation had rendered the empire’s debased coinage and the taxes collected in it virtually worthless. Therefore, only one way remained to try to increase revenue: collect more taxes in goods as well as in money. Diocletian, followed by Constantine, increased taxation “in kind,” meaning that more citizens now had to pay taxes in goods and services rather than only pay with currency. Taxes paid in coin continued, but payments of taxes in kind became a more prominent source of government revenue until the end of the fourth century A.D., when payments were more and more commuted into uncorrupted gold and silver, to make tax collection easier for imperial officials.

Taxes in kind went mostly to support the expanded number of soldiers. Payments of barley, wheat, meat, salt, wine, vegetable oil, horses, camels, mules, and so on provided food and transport animals for the army. The major sources of the payments, whose amounts varied in different regions, were a tax on land, assessed according to its productivity, and a head tax on individuals. There was no regularity to this reformed taxation system because the empire was too large and the administration too small to overcome traditional local variations. In some areas, both men and women from the age of about twelve to sixty-five paid the full tax, while in other places women paid only half the tax assessment, or none at all. Workers in cities perhaps paid taxes only on their property and not themselves, but they also periodically had to labor without pay on public works projects. Their tasks ranged from cleaning the municipal drains to repairing dilapidated buildings. Owners of urban businesses, from shopkeepers to prostitutes, still paid taxes in money. Members of the senatorial class were exempt from ordinary taxes but had to pay special levies.

Diocletian’s financial reforms provoked harmful social consequences by restricting freedom and corroding communal values among both poorer and richer citizens. Merchants had to break the law to make a profit to stay in business, while the government increasingly imposed oppressive restrictions to promote tax collection. The emperors could squeeze greater revenues from the population only if agricultural production remained stable, workers remained at their jobs, and the urban elites continued to perform public service. Therefore, imperial law now forced working people to remain where they were and to pass on their occupations to their children. Tenant farmers (coloni) completely lost the freedom to move from one landlord’s farm to another. Male tenants, as well as their wives in those areas in which women paid taxes, were now legally confined to working a particular plot. Their children were required to continue farming their family’s allotted land forever. Over time, many other occupations deemed essential were also made compulsory and hereditary, from transporting grain and baking to serving in the military. The emperors’ attempts to increase revenues also produced destabilizing social discontent among poorer citizens. When the tax rate on agricultural land eventually reached one-third of its gross yield, this intolerable burden provoked the rural farming population to open revolt in some areas, especially Spain in the fifth century A.D.

The emperors also decreed burdensome regulations for the propertied classes in the cities and towns. The men and some women from this elite socio-economic level had traditionally served as curiales (unsalaried city council members) and spent their own money to support the community. Their financial responsibilities ranged from maintaining the water supply to feeding troops, but their most expensive responsibility was paying for shortfalls in tax collection. The emperors’ demands for more and more revenue now made this a crushing duty, compounding the damage to the financial well-being of curiales that the third-century crisis had set in motion.

For centuries, the empire’s welfare had of course depended on a steady supply of public-spirited members of the social elite enthusiastically filling these crucial local posts in the towns of Italy and the provinces to win the admiration of their neighbors. As the financial pressure increased, this tradition broke down as wealthier people avoided public service to escape being bled dry. So distorted was the situation that compulsory service on a municipal council became one of the punishments for a minor crime. Eventually, to prevent curiales from escaping their obligations, imperial policy banned them from moving away from the towns where they had been born. They even had to ask official permission to travel. These laws made members of the elite eager to win exemptions from public service by exploiting their social connections to petition the emperor, by bribing higher officials, or by taking up one of the occupations that freed them from such obligations (the military, imperial administration, or the church). The most desperate curiales simply ran away, abandoning home and property when they could no longer fulfill their traditional duties. The restrictions on individual freedom caused by the vise-like pressure for higher taxes thus eroded the communal values that had motivated wealthy Romans for so long.

Following the Roman tradition of finding religious explanations for disasters, Diocletian concluded that the gods’ anger had caused the great crisis in the empire. To regain the divine goodwill on which Romans believed their safety and prosperity depended, Diocletian called upon citizens to follow the religion that had guided Rome to power and virtue in the past. As he said in an official announcement, “Through the providence of the immortal gods, eminent, wise, and upright men have in their wisdom established good and true principles. It is wrong to oppose these principles or to abandon the ancient religion for some new one” (Hyamson 15.3, pp. 131–133).

This edict specifically concerned believers in a sect formed by the third-century A.D. Iranian prophet Mani, but Christianity as a new religion received the full and violent effect of Diocletian’s belief about the cause of the empire’s troubles. Blaming Christians’ hostility to traditional Roman religion, Diocletian in A.D. 303 launched a massive attack on them known as the Great Persecution. He seized Christians’ property, expelled them from his administration, tore down churches, ordered their scriptures burned, and executed them for refusing to participate in official religious rituals. As usual, policy was applied differently in different regions because there was no effective way to police the action or inaction of local officials enforcing orders from the emperor. In the western empire, the violence stopped after about a year. In the eastern empire, it continued for a decade. The public executions of martyrs were so gruesome that they aroused the sympathy of some of their polytheist neighbors. The Great Persecution therefore had an effect contrary to Diocletian’s purpose: it undermined the peace and order of society that he intended his reforms to restore.

Constantine (ruled 306–337), Diocletian’s successor, changed the empire’s religious history forever by converting to Christianity. For the first time ever, a Roman ruler overtly proclaimed his allegiance to the religion that would eventually garner the largest number of adherents of all the world’s religions. A century earlier, Abgar VIII, ruler of the small client kingdom of Osrhoëne in northern Mesopotamia, had converted to Christianity, but now the head of the entire Roman world had aligned himself with the new faith. Constantine adopted Christianity for the same reason that Diocletian had persecuted it: in the belief that he was gaining divine protection for the empire and for himself. During the civil war that he had to fight to become emperor after Diocletian, Constantine experienced a dream vision promising him the support of the Christian God. His biographer, Eusebius, reported (Life of Constantine 1.28) that Constantine had also seen a vision of Jesus’s cross in the sky surrounded by the words, “With this sign you shall win the victory!” When Constantine finally triumphed over his rivals by winning the battle of the Milvian Bridge in Rome in A.D. 312, he proclaimed that the miraculous power of the Christians’ God had won him this victory. He therefore declared himself a Christian emperor. Several years later, to celebrate his victory, Constantine erected the famous arch that still stands today near the Colosseum. To provide decoration for it, the emperor ordered sculpted sections to be attached to it that displayed his supreme status, towering over everyone else. Constantine’s assertion that divine power lay behind his superiority was traditional for Roman emperors; his linking of that power to the Christian God was new.

Following his conversion to Christianity, Constantine did not outlaw traditional Roman religion or make his personal faith the official religion. Instead, he decreed religious toleration. The best statement of this policy survives in the so-called Edict of Milan of A.D. 313 (Lactantius, On the Death of the Persecutors 48). Building on the ideas proclaimed by Emperor Gallienus half a century earlier, this proclamation specified free choice of religion for everyone and referred to the empire’s protection by “the highest divinity”—an imprecise term meant to satisfy both Christians and traditional believers. For Constantine, religious toleration was the correct choice both to regain divine goodwill for the empire and also to prevent social unrest.

Figure 26. This coin has a profile of Emperor Constantine and a picture of his battle standard carrying the monogram for Christ (the combined Greek letters chi and rho). This sign, the Christogram, has endured as a symbol of Christianity until the present day. Photo courtesy of Classical Numismatic Group, Inc./www.cngcoins.com.

Constantine wanted to avoid angering traditional believers if at all possible because they still greatly outnumbered Christians, but he nevertheless did much to promote his newly chosen faith. For example, he began construction on the Basilica of St. John Lateran to be the home church of the bishop of Rome, as well as on an enormous basilica dedicated to St. Peter (finished in A.D. 349 after decades of construction and a center of worship for more than a thousand years until it was torn down in the sixteenth century to make way for the present building). Constantine also returned to Christians all their property that had been seized during Diocletian’s persecution, but, to pacify those non-Christians who had bought the confiscated property at auction, the emperor had the treasury compensate them financially for their loss. When in A.D. 321 Constantine made the Lord’s Day a holy occasion on which no official business or manufacturing work could be performed, he shrewdly made sure that it corresponded with “Sunday.” This name allowed polytheists to believe that a particular day of the week also continued to honor their ancient deity: the sun. Constantine’s arch acknowledged the role of divine aid in his victory, but it did not specifically mention the Christian God. And when Constantine in A.D. 324–330 built a new capital, Constantinople, on the site of ancient Byzantium (today Istanbul in Turkey) at the mouth of the Black Sea, he erected many statues of the traditional gods in the city. Most conspicuously of all, he respected Roman tradition by continuing to hold the ancient office of pontifex maximus (“highest priest”), which emperors had filled ever since Augustus. Constantine as emperor was engaged in a careful balancing act when it came to the political implications of his publicly chosen new faith because he knew full well that polytheists still outnumbered Christians in the empire’s population.

By this period, the evidence for Roman history that survives has become much more concerned than before with Christianity. It shows that the Christianization of the empire provoked strong emotional responses because ordinary people cared fervently about religion, which provided their best hope for private and public salvation in a dangerous world over which they had little control. On this point, believers in traditional religion and Christians shared some similar beliefs. Both, for instance, assigned a potent role to spirits and demons as ever-present influences on life. For some people, it seemed safest to reject neither faith. A silver spoon used in the worship of the pagan forest spirit Faunus has been found engraved with a fish; the letters spelling “fish” in Greek (ICHTHYS) were an acronym for “Jesus Christ the Son of God, the Savior” (Johns and Potter no. 67, pp. 119–121).

The overlap between some traditional religious beliefs and Christianity did not, however, mask the even greater differences between polytheists’ and Christians’ beliefs. They debated passionately about whether there was one God or many, and about what kind of interest the divinity (or divinities) took in the world of humans. Polytheists still participated in frequent festivals and sacrifices to many different gods. Why, they wondered, did these joyous occasions of worship not satisfy everyone’s yearnings for personal contact with the power of divinity?

Equally incomprehensible to traditional believers was a creed centered on a savior who had not only failed to overthrow Roman rule, but had even been executed as a common criminal. The traditional gods, by contrast, had bestowed a world empire on their worshipers. Moreover, they pointed out, cults such as that of the goddess Isis and philosophies such as Stoicism insisted that only the pure of heart and mind could be admitted to their fellowship. Christians, by contrast, sought out the impure. Why, wondered perplexed polytheists, would anyone willingly want to associate with acknowledged sinners? In any case, polytheists insisted that Christians had no right to claim they possessed the sole version of religious truth, for no doctrine that provided “a universal path to the liberation of the soul” had ever been found, as the philosopher Porphyry (A.D. 234–305) argued (Augustine, City of God 10.32).

The slow pace of religious transformation revealed how strong traditional religion remained in this period, especially at the highest social levels. In fact, Emperor Julian (ruled A.D. 361–363) rebelled against his family’s Christianity and tried to restore polytheism as the leading religion. A deeply pious person, Julian believed in a supreme deity corresponding to Greek philosophical ideas: “This divine and completely beautiful universe, from heaven’s highest arch to earth’s lowest limit, is tied together by the continuous providence of god, has existed ungenerated eternally, and is imperishable forever” (Oration 4.132C). Julian’s policy failed, however, because his religious vision struck most people as too abstract and his public image as too pedantic. When he lectured to a large audience in Antioch, the crowd made fun of his philosopher’s beard instead of listening to his message. Still, this “apostate” emperor had his admirers, such as the upper-class army officer and historian Ammianus Marcellinus of Antioch. He documented Julian’s strife-filled reign in his detailed work of the history of his own times, drawing on his personal experience at court and on the battlefield to give a vivid description of this turbulent era.

The Christian emperors chipped away at traditional religion by slowly removing polytheism’s official privileges and financial support. In A.D. 382 came the highly symbolic gesture of removing the altar and statue of the ancient deity Victory, which had stood in the Senate House in Rome for centuries. Ending government payment for animal sacrifices to the gods was even more damaging. Symmachus (A.D. 340–402), a pagan senator who held the prestigious post of prefect (“mayor”) of Rome, objected to what he saw as an outrage to Rome’s tradition of religious diversity. Speaking in a last public protest against the new religious order, he argued: “We all have our own way of life and our own way of worship.… So vast a mystery cannot be approached by only one path” (Relatio 3.10).

Christianity’s growing support from the imperial government combined with its religious and social values to help it to gain more and more believers. They were attracted by Christians’ strong sense of community in this world, as well as by the promise of salvation in the world to come after death. Wherever Christians traveled or migrated in this period, they could find a warm welcome in the local congregation. The faith also won converts by emphasizing charitable works, such as caring for the poor, widows, and orphans. By the mid-third century A.D., for example, Rome’s congregation was supporting fifteen hundred widows and other impoverished persons. Christians’ hospitality, fellowship, and philanthropy to one another were enormously important because people at that time had to depend mostly on friends and relatives for advice and practical help. State-sponsored social services were rare and limited. Soldiers also now found it comfortable to convert and continue to serve in the army. Previously, Christian soldiers had sometimes created disciplinary problems by renouncing their military oath. As an infantry officer named Marcellus had said at his court martial in A.D. 298 for refusing to continue his duties, “A Christian fighting for Christ the Lord should not fight in the armies of this world” (Acts of Marcellus 4). Once the emperors had become Christians, however, soldiers could justify military duty to themselves as serving the affairs of Christ.

Christianity officially replaced traditional polytheism as the state religion in A.D. 391, when Emperor Theodosius (ruled A.D. 379–395) succeeded where his predecessors had failed: he enforced a ban on animal sacrifices, even if private individuals paid for them. Also rejecting the title of pontifex maximus, he made divination by the inspection of the entrails of animals punishable as high treason and closed and confiscated all temples. Many shrines, among them the famous Parthenon in Athens, subsequently became Christian churches. Theodosius did not, however, require anyone to convert to Christianity, and he did not forbid non-Christian schools. The Academy teaching Plato’s philosophy in Athens, for instance, continued for another 140 years. Capable non-Christians such as Symmachus continued to find government careers under the Christian emperors. But traditional believers were now the outsiders in an Empire that had officially been transformed into a monarchy devoted to the Christian God. Polytheist adherents continued to exist for a long time and to practice their religion as best they could privately. This was easier to do in remote locations in the countryside than in cities filled with inquisitive neighbors. For this reason, Christians came to refer to traditional believers as “pagans” (pagani, the Latin for “country bumpkins”).

Tensions between Christians and pagans could generate violence, especially when conflict over political influence was involved. In A.D. 415 in Alexandria in Egypt, for example, Hypatia, the most famous woman scholar of the time and a pagan, was torn to pieces in a church by a Christian mob. Her lectures had gained her a great reputation as a mathematician and expert in the philosophy of Plato. Her fame gave her influence with the Roman official in charge of Alexandria (himself a pagan) and aroused the jealousy of Cyril, the bishop of Alexandria. Rumor had it that Cyril secretly instructed an underling to stir up the crowd that murdered Hypatia (Socrates, Church History 7.15).

Judaism posed a special problem for the emperors in an officially Christian empire. Like pagans, Jews rejected the new state religion. On the other hand, Jews seemed entitled to special treatment because Jesus had been a Jew and because previous emperors had allowed Jews to practice their religion, even after Hadrian’s refounding of Jerusalem as a Roman colony. Therefore, the Christian emperors compromised by allowing Judaism to continue, while imposing increasing legal restrictions on its adherents. For instance, imperial decrees eventually banned Jews from holding government posts but required them to assume the financial burdens of curiales without receiving the honorable status of that rank. In addition, each Jew had to pay a special tax to the imperial treasury every year. By the late sixth century A.D., the law barred Jews from making wills, receiving inheritances, or testifying in court.

Although these developments began the long process that made Jews into second-class citizens in later European history, they did not disable their religion. Magnificent synagogues continued to exist in Palestine, where a few Jews still lived; most of the population had been dispersed throughout the cities of the empire and the lands to the east. The scholarly study of Jewish law and tradition flourished in this period, culminating in the production of the learned texts known as the Palestinian and the Babylonian Talmuds and the scriptural commentaries of the Midrash. These works of religious scholarship laid the foundation for later Jewish life and practice.

The contributions of women continued to be a crucial factor in Christianity’s growing strength as the official religion of the Roman state. Women’s exclusion from public careers—other than the burdens of curial office—motivated them to become active church participants. The famous Christian theologian Augustine eloquently recognized the value of women in strengthening Christianity in a letter he wrote to the un-baptized husband of a baptized woman: “O you men, who fear all the burdens imposed by baptism! Your women easily surpass you. Chaste and devoted to the faith, it is their presence in large numbers that causes the church to grow” (Letters 2*). Some women earned exceptional fame and status by giving their property to their congregation, or by renouncing marriage to dedicate themselves to Christ. Consecrated virgins and widows who chose not to remarry thus joined large donors as especially respected women.

Christianity also grew stronger from its continued success in consolidating a formal leadership hierarchy. By now, a rigid organization based on the authority of bishops—all male—had fully replaced early Christianity’s relatively looser, more democratic structure, in which women were also leaders. In the new state-supported church, the extent of the bishops’ power grew so much greater that it came to resemble, on a smaller scale of course, that of the emperors. Bishops in the late Empire ruled their flocks almost as monarchs, determining their membership and controlling their finances.

The bishops in the largest cities—Rome, Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch, Carthage—became the most powerful leaders among their colleagues. The main bishop of Carthage, for example, oversaw at least a hundred local bishops in the surrounding area. Regional councils of bishops exercised supreme authority in appointing new bishops and deciding the doctrinal disputes that increasingly arose.

The bishop of Rome eventually emerged as the church’s supreme leader in the western empire. This bishop eventually claimed the title of “Pope” (from pappas, a Greek word for “father”), which still designates the head of the Roman Catholic Church. The popes based their claim to preeminence on the passage in the New Testament in which Jesus speaks to the apostle Peter: “You are Peter, and upon this rock I will build my church.… I will entrust to you the keys of the kingdom of heaven. Whatever you bind on earth shall be bound in heaven. Whatever you loose on earth shall be loosed in heaven” (Matthew 16: 18–19). Because Peter’s name in Greek and Aramaic means “rock” and because he was seen as the first bishop of Rome, later popes claimed that this passage authorized their superior position.

Christianity’s official status did not bring unity in belief and practice. Disputes centered on what constituted orthodoxy as opposed to heresy. The emperors became the final authority for enforcing orthodox creeds (summaries of beliefs) and could use force to compel agreement when disputes became so heated that disorder or violence resulted.

Subtle theological questions about the nature of the Trinity of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit caused the bitterest disagreements. Arianism, named after Arius of Alexandria (A.D. 260–336), generated tremendous conflict by insisting that God the Father had created Jesus his son from nothing and granted him his special status. Thus, Jesus was not co-eternal with the Father, having been created by him, and divine not on his own, but because God had made him so as his son. Arianism appealed to ordinary people because its subordination of son to father corresponded to the norms of family life. Arius used popular songs to make his views known, and people everywhere became engrossed in the controversy. “When you ask for your change from a shopkeeper,” one observer remarked in describing Constantinople, “he lectures you about the Begotten and the Un-begotten. If you ask how much bread costs, the reply is that ‘the Father is superior and the Son inferior’; if in a public bath you ask ‘Is the water ready for my bath?’ the attendant answers that ‘the Son is of nothing’” (Gregory of Nyssa, On the Deity of the Son and the Holy Spirit in J.-P. Migne, Patrologia Graeca vol. 46, col. 557b).

Many Christians became so incensed over this apparent demotion of Jesus that Constantine had to intervene to try to restore order. In A.D. 325 he convened 220 bishops to hold the Council of Nicea to settle the dispute over Arianism. The bishops declared that the Father and the Son were indeed “of one substance” and co-eternal. So fluid were Christian beliefs in this period, however, that Constantine later changed his mind on the doctrine twice, and the heresy lived on; many of the Germanic peoples who later came to live in the empire converted to Arian Christianity.

The disagreements could be complicated. Nestorius, for example, a Syrian who became bishop of Constantinople in A.D. 428, insisted that Christ paradoxically incarnated two separate beings, one divine and one human. Orthodox doctrine regarded Christ as a single being with a double nature, simultaneously God and man. Expelled by the church hierarchy, Nestorian Christians moved to Persia, where they generally enjoyed the support of its non-Christian rulers. They established communities that still endure in Arabia, India, and China. Similarly, Monophysites—believers in a single divine nature for Christ—founded independent churches in Egypt, Ethiopia, Syria, and Armenia beginning in the sixth century A.D.

No heresy better illustrates the ferocity of Christian disputes than Donatism. Followers of the fourth-century North African priest Donatus insisted that they could not readmit to their congregations any members who had cooperated with imperial authorities to avoid martyrdom during the Great Persecution of Diocletian. Feelings reached such a fever pitch that they violently split families, as in one son’s threat against his mother: “I will join Donatus’s followers, and I will drink your blood” (Augustine, Letters 34.3).

Augustine (A.D. 354–430) became the most important thinker in establishing the western church’s orthodoxy as religious truth. The pagan son of a Christian mother and a pagan father in North Africa, he began his career by teaching rhetoric. In A.D. 386, he converted to Christianity under the influence of his mother and Ambrose, the powerful bishop of Milan. In A.D. 395 Augustine became a bishop in his homeland, but his reputation rests not on his church career but on his writings. For the next thousand years Augustine’s works would be the most influential doctrinal texts in western Christianity next to the Bible. He wrote so much about religion and philosophy that a later scholar declared: “The man lies who says he has read all your works” (Isidore of Seville, Carmina in J.-P. Migne, Patrologia Latina vol. 83, col. 1109a).

Augustine in his book City of God explained that people were misguided to look for true value in their everyday lives because only life in God’s heavenly city had meaning. The imperfect nature of earthly existence demanded secular law and government to prevent anarchy. The doctrine of original sin—a subject of theological debate since at least the second century A.D.—meant that people suffered from a hereditary moral disease turning their will into a disruptive force. This inborn corruption, Augustine argued, required governments to use coercion to suppress evil. Civil government was necessary to impose moral order on the chaos of human life after humanity’s fall from grace in the Garden of Eden. The state therefore had a right to compel people to remain united to the church, by force if necessary.

Order in society was so valuable, Augustine insisted, that it could even make the inherently evil practice of slavery into a source of good. Corporal punishment and enslavement were lesser evils than the violent troubles that disorder created. Christians therefore had a duty to obey the emperor and participate in political life. Soldiers, too, had to follow their orders. Torture and the death penalty, on the other hand, had no place in a morally upright government.

Augustine also insisted that sex automatically plunged human beings into sin and that the only pure life was asceticism (a life of denial of all bodily pleasures). Augustine knew from personal experience how difficult this was: he revealed in his autobiographical work Confessions that he felt a deep conflict between his sexual desire and his religious philosophy. For years he followed his natural urges and had sex frequently outside marriage, including fathering a son by a mistress. Only long reflection, he explained, gave him the inner strength to pledge his future chastity as a Christian.

Augustine advocated sexual abstinence as the highest course for Christians because he believed Adam and Eve’s disobedience in the Garden of Eden had forever ruined the original, perfect harmony God created between the human will and human passions. God punished his disobedient children by making sexual desire a disruptive force that they could never completely control through their will. Although Augustine reaffirmed the value of marriage in God’s plan, he added that sexual intercourse even between loving spouses carried the melancholy reminder of humanity’s fall from grace. A married couple should “descend with regret” to the duty of procreation, the only acceptable reason for sex (Sermon on the New Testament 1.25). Married couples should not take pleasure in intercourse, even when fulfilling their social responsibility to produce children.

This doctrine elevated chastity to the highest level of moral virtue. In the words of the biblical scholar Jerome (A.D. 348–420), living this spotless life counted as “daily martyrdom” (Letters 108.32). Sexual renunciation became a badge of honor, as illustrated by the inscription on the tombstone of a thirty-nine-year-old Christian woman in Rome named Simplicia: “She paid no heed to producing children, treading beneath her feet the snares of the body” (L’Année épigraphique 1980, no. 138, p. 40). This self-chosen holiness gave women the status to demand more privileges, such as education in Hebrew and Greek to be able to read the Bible for themselves. By the end of the fourth century A.D., the importance of virginity as a Christian virtue had grown so large that congregations began to call for virgin priests and bishops. This demand represented a dramatic change because traditionally virginity had been a state of chastity that Roman society required only of women, before marriage.

Christian asceticism reached its peak in monasticism. Monks (from the Greek monos, originally meaning “single, solitary”) and nuns (from the Latin nonna, originally meaning an older unmarried woman) were men and women who withdrew from society to live a life of extreme self-denial demonstrating their devotion to God. Both polytheism and Judaism had long traditions of a few people living as ascetics, but what made Christian monasticism distinctive was the number of people choosing it and the heroic status that they earned. Christian monks’ and nuns’ high reputations came from their abandoning ordinary pleasures and comforts. They left behind their families and congregations, renounced sex, worshiped constantly, wore the roughest, often unisex form of clothing, and—most difficult of all, they reported—ate only enough to prevent starvation. Monastic life was a constant spiritual struggle—these religious ascetics frequently dreamed of plentiful, tasty food, more often even than of sex.

The earliest Christian monks emerged in Egypt; among the earliest to make this radical choice in lifestyle was a prosperous farmer named Antony (A.D. 251–356). One day around A.D. 285 he abruptly abandoned all his property after hearing a sermon based on Jesus’s admonition to a rich young man to sell his possessions and give the proceeds to the poor (Matthew 19:21). Placing his sister in a community of virgins, Antony spent almost all the rest of his time in a barren existence in the desert as a hermit to demonstrate his heroism for God, leading others to emulate him in choosing this demanding life of deprivation; he was later recognized as a saint.

Monasticism appealed for many reasons, but above all because it gave ordinary people a way to become heroes in the traditional ancient Greek religious sense (human beings with extraordinary achievements, who after their deaths retained the power to help the living). Becoming a Christian ascetic served as a substitute for the glory of martyrdom, which Constantine’s conversion had made irrelevant. “Holy women” and “holy men” attracted great attention with feats of pious endurance. Symeon (A.D. 390–459) lived atop a tall pillar for thirty years, preaching to the people gathered at the foot of his perch. Egyptian Christians came to believe that the monks’ and nuns’ supreme piety as living heroes ensured the annual flooding of the Nile, the duty once associated with the magical power of the ancient pharaohs. Christian ascetics with reputations for exceptional holiness exercised influence even after death. Their relics—body parts or clothing—became treasured sources of protection and healing for worshipers.

The earliest monks and nuns lived alone or in isolated tiny groups, but by A.D. 320 larger single-sex communities had sprung up along the Nile River so that Christian ascetics living together in greater numbers could encourage one another along the harsh road to heroic holiness. Some monastic communities imposed military-style discipline, but they differed in allowing contact with the outside world. Some aimed for complete self-sufficiency to avoid interaction with the outside world. Basil (“the Great”) of Caesarea (A.D. 330–379), however, started the competing tradition that monks should do good in society. For example, he required his monks to perform charitable service in the outside world, such as ministering to the sick. This practice led to the foundation of the first nonmilitary hospitals, attached to monasteries.

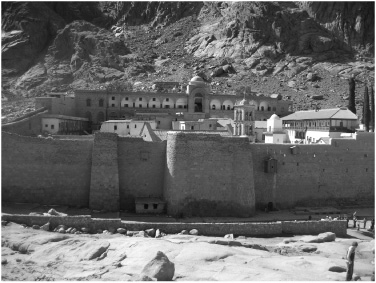

Figure 27. St. Catherine’s Monastery on Mount Sinai was established at the site where Moses was believed to have seen the burning bush; built in the sixth century A.D., it is still operating. ccarlstead/Wikimedia Commons.

The level of asceticism enforced in monastic communities also varied significantly. The followers of Martin of Tours (A.D. 316–397), an ex-soldier famed for his pious deeds, organized groups famed for their harshness. A milder code of monastic conduct, however, exerted more influence on later worship traditions. Called the Benedictine Rule after its creator, Benedict of Nursia in central Italy (A.D. 480–553), it prescribed a daily routine of prayer, scriptural readings, and manual labor. The Rule divided the day into seven parts, each with a compulsory service of prayers and lessons, but no Mass. The required worship for each part of the day was called the liturgy (literally, “public work” and, by extension, the services of the church). This arrangement became standard practice. Unlike the harsh regulations of Egyptian and Syrian monasticism, Benedict’s code did not isolate his monks from the outside world or deprive them of sleep, adequate food, or warm clothing. Although it gave the abbot (the head monk) full authority, it instructed him to listen to what every member of the community, even the youngest monk, had to say before deciding important matters. He was not allowed to beat them for lapses in discipline except when they refused to respond to correction. Nevertheless, monasticism was always a demanding, harsh existence. Jerome, himself a monk in a monastery for men that was located next to one for women, once gave this advice to a mother who decided to send her young daughter to a monastic community: “Let her be brought up in a monastery, let her live among virgins, let her learn to avoid swearing, let her regard lying as an offense against God, let her be ignorant of the world, let her live the angelic life, while in the flesh let her be without the flesh, and let her suppose that all human beings are like herself” (Letters 107.13). When the girl reached adulthood as a virgin, he added, she should avoid the baths so she would not be seen naked or give her body pleasure by dipping in the warm pools. Jerome promised that God would reward the mother with the birth of sons in compensation for the dedication of her daughter.

By the early fifth century A.D., many adults were also joining monastic communities to flee obligations and social restrictions. Parents also gave children to monastic communities to raise as offerings (“oblations”) to God and, sometimes, to escape the practical burdens and expenses of child rearing. Adult men would flee military service. Women could sidestep the outside world’s restrictions on their ambitions and freedom. Jerome well explained this latter attraction: “[As monks] we evaluate people’s virtue not by their gender but by their character, and deem those to be worthy of the greatest glory who have renounced both status and riches” (Letters 127.5). This open-minded attitude helped monasticism attract a steady stream of adult adherents eager to serve God in this world of troubles and achieve salvation in the world of bliss to come.