ELEVEN

GEOGRAPHY IS DESTINY

WHERE JOBS DISAPPEAR

When jobs leave a city or region, things go downhill pretty fast.

Youngstown, Ohio, immortalized in the Bruce Springsteen song, is a poster child for postindustrial cities hit by job loss. The city rose to prominence as a hub of steel manufacturing in the early to mid-twentieth century. Youngstown Sheet and Tube, US Steel, and Republic Steel each built major steel mills in the city that supported thousands of workers. The population of the city grew from 33,000 in 1890 to 170,000 in 1930 as the industry boomed. Good jobs were so abundant that Youngstown had one of the highest median incomes in the country and was fifth in the nation in its rate of home ownership—it was known as the “city of homes.” The city’s steel industry was considered pivotal to national security; when union workers threatened to strike during the Korean War in 1952, President Truman ordered the Youngstown Sheet and Tube mills in Chicago and Youngstown seized by the government to keep production high.

For most of the twentieth century, Youngstown’s culture was proud and vibrant. Two major department stores occupied downtown, as did four upscale movie theatres that showed the latest films. There was also a public library, an art museum, and two large, elaborate public auditoriums. The city organized an annual “community chest” to help the needy. Steelwork was central to the city’s identity—a local church featured an image of a mill worker with the quote “The voice of the Lord is mighty in operation.”

The steel industry began to face global competition throughout the 1960s and 1970s. Youngstown Sheet and Tube merged with Lykes Corporation, a steamship company based in New Orleans, in 1969. The mills were not reinvested in as corporate ownership left the city—the workers knew that their mills were not state-of-the-art and continuously agitated for more investment. Then, on “Black Monday,” September 19, 1977, Youngstown Sheet and Tube announced that it was closing its large local mill. Republic Steel and US Steel followed suit. Within five years, the city lost 50,000 jobs and $1.3 billion in manufacturing wages. Economists coined the term “regional depression” to describe what occurred in Youngstown and the surrounding area.

Local church and union leaders organized in response to the mill closings, forming a coalition that included national outreach, a legislative agenda, and occupying corporate headquarters in protest. They succeeded in prompting Congress to pass a law saying that plant shutdowns should have more notice. They tried to engineer a worker takeover of one of the mills. Government loan programs made it possible for some ex-steelworkers to attend Youngstown State University to retrain.

These efforts were largely futile at preserving residents’ way of life. The mills stayed closed and local unemployment surged to Depression-era levels of 24.9 percent by 1983. A record number of bankruptcies and foreclosures followed, as property values plummeted. Arson became commonplace, with an average of two houses per day lit on fire through the early 1980s, in part by homeowners trying to collect on insurance policies. The city was transformed by a psychological and cultural breakdown. Depression, child and spousal abuse, drug and alcohol abuse, divorces, and suicide all became much more prevalent; the caseload of the area’s mental health center tripled within a decade. During the 1990s, Youngstown’s murder rate was eight times the national average, six times higher than New York’s, four and a half times that of Los Angeles, and twice as high as Chicago’s.

Through the 1990s, local political and business leaders kept seeking new opportunities for economic development. First it was warehouses. Then telemarketing. Then minor league sports. Then prisons—four were built in the region, which added 1,600 jobs but brought other issues. Many residents were concerned about the perception of Youngstown as a “penal colony.” One prison run by a private corporation was so lax that six prisoners, including five convicted murderers, escaped at midday in July 1998 and the officials didn’t notice until notified by other inmates. National press descended on Youngstown, and the prison company apologized and paid the city $1 million to account for police overtime capturing the escapees. Another prison run by the county was forced to release several hundred prisoners early in 1999 because of inadequate staffing and budget shortfalls. In 1999, a 20-year investigation convicted over 70 local officials of corruption, including the chief of police, the sheriff, the county engineer, and a U.S. congressman.

In 2011, the Brookings Institution found that Youngstown had the highest percentage of its citizens living in concentrated poverty out of the top 100 metropolitan areas in the country. In 2002, the city unveiled the “Youngstown 2010” plan. The 2010 plan was an attempt at “smart shrinkage” through targeted investment and relocating people from low-occupancy areas to more viable neighborhoods. The national media touted the 2010 plan as a blueprint for postindustrial cities, and the mayor toured the country to promote it. I love the realism behind the 2010 plan. Yet, it proved to be hard to execute—the city did not succeed in meaningfully relocating citizens from low-occupancy areas and failed to complete its demolition plan.

Youngstown has been the fastest-shrinking city in the U.S. on a percentage basis since 1980. The population was down to 82,000 in 2000. Today it’s about 64,000. Its largest employer now is the local university. “Youngstown’s story is America’s story, because it shows that when jobs go away, the cultural cohesion of a place is destroyed. The cultural breakdown matters even more than the economic breakdown,” said John Russo, professor of labor studies at Youngstown State University. Echoed journalist Chris Hedges in 2010, “Youngstown, like many postindustrial pockets in America, is a deserted wreck plagued by crime and the attendant psychological and criminal problems that come when communities physically break down.”

Many young people left Youngstown to look for better opportunities elsewhere. One of those who stayed around, Dawn Griffin, single mother of three, struggles to find employment. Although attached to her hometown, she is also planning on moving away in the next couple of years, because there are no opportunities for her and her children in the area. Nostalgic, she remembers the better years of her childhood when her father was working at the steel mills: “I thought we were rich.” She still wonders what is going to happen to her hometown: “There is nothing but concrete left here.”

The patterns one sees in Youngstown with the decimation of jobs—increased social disintegration, criminality, public corruption, desperate attempts at economic development, human capital flight—are not unique. They apply in other cities that have seen similar loss of industry.

Gary, Indiana, is another steel town that lost jobs when the mills closed. It was the hometown of Michael Jackson and Janet Jackson back in the 1960s and many locals describe growing up there as ideal. After its decline, it became known as a murder capital, reaching number one in per capita homicide rate in the United States in 1993. In 1992, 20 local police officers were indicted on federal charges of racketeering and drug distribution. In 1996, in a bid for new jobs, the city welcomed two casino boats and legalized gambling on the shore of Lake Michigan. In 2003, the city invested $45 million in a minor league baseball stadium meant to revitalize the economy, to disappointing results. In 2014, a serial killer confessed to killing at least seven people in Gary and depositing bodies in abandoned houses. Today almost 40 percent of residents live in poverty, and more than 25 percent of the city’s 40,000 homes are abandoned. The city lacks the money to demolish derelict properties and is considering cutting off services to many neighborhoods. Its population peaked at 173,320 in 1960 and is down to about 77,000 as of 2016.

Ruben Roy, an 85-year-old former steelworker, recalled how beautiful Gary used to be and how easy it was to get a job when he started. “I started off working with a shovel and pick, shoveling and picking at things, but those jobs are gone. They got machines to shovel and pick now. The world has changed. Back in my day you needed a strong back and a weak mind to get a job. Now you need a weak back and a strong mind. I would tell the kids to leave. Go get an education and go to where the jobs and opportunities are. They are not here in Gary any more.”

Said Imani Powell, a 23-year-old server at the local Buffalo Wild Wings who returned to Gary after one year in college in Arizona to be close to her mom and sister, “I really would like to move someplace more beautiful, where you don’t have to worry about abandoned buildings. There are just so many here. It scares me to walk by them; I don’t want to end up a body lost in one of them. It is complicated for people who live in Gary. They don’t want to move because this is what they are used to. Do you want to go and do your own thing, or be with your family? They say places are what you make of them, but it’s hard to make something beautiful when it is shit.”

The city of Camden, New Jersey, is another example of what happens when industry declines. Camden companies employed thousands of manufacturing workers in shipbuilding and manufacturing in the 1950s. Camden is also the home of Campbell Soup, which was founded in 1869. After reaching a peak of 43,267 manufacturing jobs in 1950, Camden’s employment base declined to only 10,200 manufacturing jobs by 1982. To respond, Camden opened a prison in 1985 and a massive trash-to-steam incinerator in 1989. Three Camden mayors were jailed for corruption between 1981 and 2000. As of 2006, 52 percent of the city’s residents lived in poverty and the city had a median household income of only $18,007, making it America’s poorest city. In 2011, Camden’s unemployment rate was 19.6 percent. Camden had the highest crime rate in the United States in 2012, with 2,566 violent crimes for every 100,000 people, 6.6 times the national average. The population declined from 102,551 in 1970 to 74,420 in 2016. “Between 1950 and 1980… patterns of social pathology emerged [in Camden] as real elements of everyday life,” wrote Howard Gillette Jr., a history professor at Rutgers. “Camden and the great majority of its citizens remain, after the fall, strivers for that illusive urban renewal that invests as much in human lives as it does in monetary return.”

Matt Taibbi in Rolling Stone described Camden as “a major metropolitan area run by armed teenagers with no access to jobs or healthy food” in 2013, noting that 30 percent of the population was 18 or younger. Between 2010 and 2013, the state of New Jersey cut back on subsidies that supported many of the services in Camden, resulting in a surge in violent crime. The crime rate “put us somewhere between Honduras and Somalia,” said Police Chief J. Scott Thomson.

The county took over policing later in 2013 and installed a $4.5 million security center as well as 121 security cameras and 35 microphones to detect gunshots and other incidents, which has brought some degree of stability and a decline in violence.

These brief descriptions are by no means full histories of these communities. For example, they gloss over the racial dynamics that each city experienced, as each underwent “white flight” during their declines. They also pay short shrift to the many heroic efforts to improve matters on the ground on a daily basis—I naturally root for the people who stuck around.

The central point is this: In places where jobs disappear, society falls apart. The public sector and civic institutions are poorly equipped to do much about it. When a community truly disintegrates, knitting it back together becomes a herculean, perhaps impossible task. Virtue, trust, and cohesion—the stuff of civilization—are difficult to restore. If anything, it’s striking how public corruption seems to often arrive hand-in-hand with economic hardship.

Many entrepreneurs have experienced the difference between being part of a growing company and being part of one that is shrinking and failing. In a growing organization, people are more optimistic, imaginative, courageous, and generous. In a contracting environment, people can become negative, political, self-serving, and corrupt. You see the lesser side of human nature in most startups that fail. The same is true for communities, only amplified.

One of the great myths in American life is that everything self-corrects. If it goes down, it will come back up. If it gets too high, it will come back down to earth. Sometimes things just go up or down and stay that way, particularly if many people leave a place. It’s understandable—no parent wants to stick around the murder capital if they can simply move.

Youngstown, Gary, and Camden are all extreme cases. It’s unlikely that their situations will be replicated in cities around the country. But they are useful as glimpses into what a future without jobs can do to a community without something dramatic filling the void.

CHANGE CAN BE A FOUR-LETTER WORD

One of the first times I visited Ohio, a friendly woman commented to me, “You know, change is a four-letter word around here. The only change we’ve seen the last 20 years has been bad.” I didn’t really understand what she meant. I couldn’t fathom how someone could have such a negative outlook.

Months later, I was chatting with a venture capitalist in San Francisco, Jared Hyatt, about helping the Midwest. He said, “I was raised in Ohio. No one from my family is still there—all of us left.” We mentioned another friend from Cleveland whom I went to Exeter with. He went to Yale and now works at Facebook in Silicon Valley.

There’s a truism in startup world: When things start going very badly for a company, the strongest people generally leave first. They have the highest standards for their own opportunities and the most confidence that they can thrive in a new environment. Their skills are in demand, and they feel little need to stick around.

The people who are left behind tend to be less confident and adaptable. It’s one reason why companies go into death spirals—the best people leave when they see the writing on the wall and the company’s decline accelerates.

The same is often true for a community.

When jobs and prosperity start deserting a town, the first people to leave are the folks who have the best opportunities elsewhere. Relocating is a significant life change—moving away from friends and family requires significant courage, adaptability, and optimism.

Imagine living somewhere where your best people always leave, where the purpose of excelling seems to be to head off to greener pastures. Over time it would be easy to develop a negative outlook. You might double down on pride and insularity. The economist Tyler Cowen observed that since 1970 the difference between the most and least educated U.S. cities has doubled in terms of average level of education—that is, more and more educated people are congregating in the same cities and leaving others.

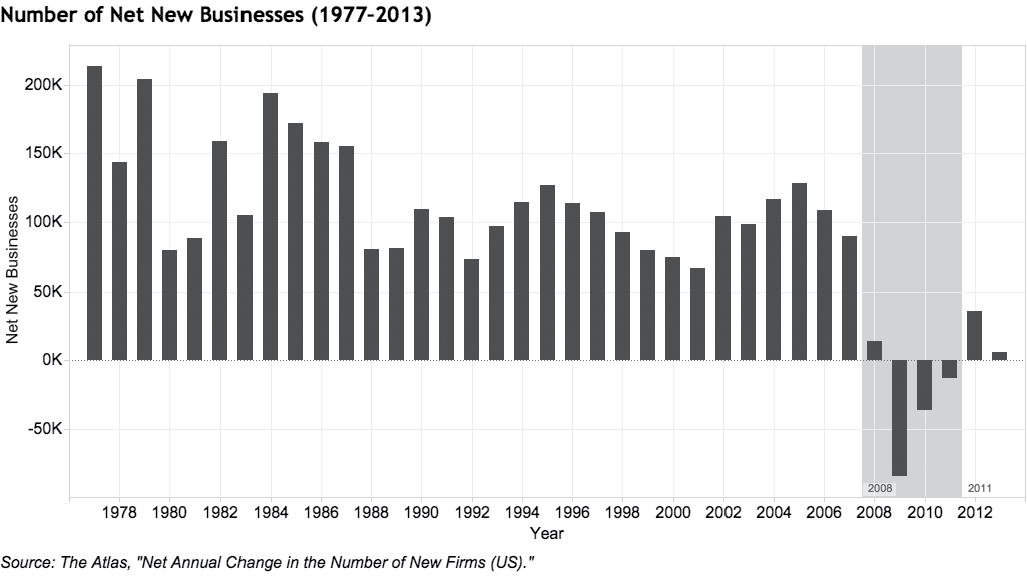

Business dynamism is now vastly unevenly distributed. Fifty-nine percent of American counties saw more businesses close than open between 2010 and 2014. During the same period, only five metro areas—New York, Los Angeles, Miami, Houston, and Dallas—accounted for as many new businesses as the rest of the nation combined. California, New York, and Massachusetts accounted for 75 percent of venture capital in 2016, leaving 47 states to compete for the remaining 25 percent. Historically, virtually all American cities had more businesses open than close in a given year, even during recessions. After 2008, that basic measurement of dynamism collapsed. A majority of cities had more businesses close than open, and this has continued to be the case for seven years after the financial crisis. The tide of businesses is no longer coming in, but going out in the majority of metro areas.

In part because regions have been diverging so sharply, the U.S. economy has become dramatically less dynamic the last 40 years. The rate of new business formation has declined precipitously during this period.

Compounding the problem is that Americans now move across state lines and change jobs at lower rates than at any point in the last several decades. The annual rate of interstate relocation dropped from about 3.5 percent of the population in 1970 to about 1.6 percent in 2015. The surge in regional inequality has coincided with a surge not in people moving, but of people staying put.

A series of studies by the economists Raj Chetty and Nathaniel Hendren showed how important where you grow up is to your future prospects. Low-income children who grew up in certain counties—Mecklenburg County, North Carolina; Hillsborough County, Florida; Baltimore City County, Maryland; Cook County, Illinois—grew up to earn 25 to 35 percent less than other low-income children who grew up in better areas. The best areas for income mobility—San Francisco; San Diego; Salt Lake City; Las Vegas; Providence, Rhode Island—have elementary schools with higher test scores; a higher share of two-parent families; greater levels of involvement in civic and religious groups; and more residential integration of affluent, middle-class, and poor families. If a child from a low-mobility area moved to a better-performing area, each year produced positive effects on his or her future earnings. They were also more likely to attend college, less likely to become single parents, and more likely to earn more with each year spent in the better environment.

It may come as a surprise that Americans are now less likely to start a business, move to another region of the country, or even switch jobs now than at any time in modern history. The most apt description of our economy is the opposite of dynamic—it’s stagnant and declining.

MANY DIFFERENT ECONOMIES

During my travels, I’ve been blown away by the disparities between America’s regions and their economic prospects. At the high end, you have the major hubs and coastal cities that are vibrant, competitive, expensive, and dominated by a shifting host of name-brand firms. Here, you see continuous construction, incoming college graduates, and a sense of cultural vitality. People of color and immigrants are abundant. Growth rates are high and new businesses commonplace.

You also see high prices. In Manhattan, apartments sell for more than $1,500 per square foot, so a 2,000-square-foot apartment might cost about $3 million. The median value of a home in the United States is $200,000, and the average list price of homes currently for sale is about $250,000. So a 2,000-square-foot apartment in Manhattan might cost 12 to 15 times what a home would cost someplace else. The premium prices extend to the grocery store, where a single-serving yogurt might run you $2. It costs $15 in tolls just to drive into the city. Movie tickets are $16.50. Parking the family Subaru in the local garage costs $500 a month, which is what many people elsewhere might pay in rent. You see lots of people wearing sweatpants and sweatshirts with the names of where they went to school: Yale, University of Pennsylvania, Middlebury.

In San Francisco and Silicon Valley, they don’t advertise where they went to school but the prices are just as exorbitant. Very normal-looking houses go for $2 million plus in Palo Alto and Atherton. The corporate headquarters of Google, Facebook, Airbnb, and Apple are insider tourist attractions. For the average tech worker, you wake up and drive from a leafy suburb to a grounded spaceship and stay there to eat the subsidized gourmet dinner. Or maybe you bike to your downtown office or take the dark-windowed company bus from San Francisco and tap out emails with headphones on. You think about money and housing a lot but don’t talk about it. Most people are transplants.

The atmosphere is quite different in mid-sized cities like Cincinnati or Baltimore, which are typically anchored by a handful of national institutions—Procter and Gamble, Macy’s, and Kroger in Cincinnati; or Johns Hopkins, T. Rowe Price, and Under Armour in Baltimore. These regions are generally in a state of equilibrium, with the anchor institutions investing in community growth while organizations rise and fall around them. Costs are average. When new construction appears, everyone knows what it is because there have been tons of news stories about it. Occasionally one of the major companies in the region starts to stumble, and the locals start to freak out. People move to these cities to work at one of the big companies, but a high proportion of residents and workers were born in the region. If you grew up in Cincinnati or Baltimore and go to college, you’ll likely think long and hard about leaving. The vibe in these cities is pleasantly gritty—a blend of normalcy, functionality, and affordability.

Then there are the former industrial towns that have hit hard times. Detroit, St. Louis, Buffalo, Cleveland, Hartford, Syracuse, and many other cities fall into this category. They often feel frozen in time, as they were built up during the middle of the 20th century and then turned to managing various challenges. There are large buildings and parts of town that have been abandoned as their populations have diminished progressively. Detroit, the most famous example, today has 680,000 people in a city that once housed 1.7 million.

The postindustrial cities have a world of potential, but the mood in many is quite tough. There’s a lot of negativity and a lack of confidence. Many people apologize for their own city and mock it, often because they’re comparing it to other places or its own past. A friend of mine moved to Missouri from California, and he said that people asked him over and over again, “Why would you ever do that?” A Cleveland transplant from DC made the same observation and said, “People here need to stop apologizing or making jokes.”

The positive manifestation is to develop a chip on their shoulder, like “Detroit Hustles Harder.” I tend to like places that adopt an attitude.

One thing that has surprised me is that many of these places—Baltimore, St. Louis, New Orleans, Detroit, Cleveland—have a casino smack dab in the middle of their downtown. I’ve visited some of them on a weeknight and they are not encouraging places. Most of the people there do not seem like they should be gambling.

Once when I was on the road in the Midwest I ate lunch in a Chinese restaurant that had seen better days. In the bathroom, one of the urinals was broken and covered with duct tape. I thought to myself, “They should really fix that.” Then I reflected on the owners’ thought process. They probably have razor-thin margins. If they spent a couple hundred dollars on fixing the urinal, it may not make any difference to their flow of customers. I imagined for a second that they became really optimistic and spent a couple thousand dollars sprucing up the place. The local area was clearly losing population and there was no guarantee a revamp would generate new business. I realized that, if you’re managing in a contracting environment, it’s possible that leaving the urinal duct-taped might be a perfectly reasonable way to go. Optimism could be stupid. When you’re used to losing people and resources, you make different choices.

Finally, there are the small towns on the periphery, places that feel like they have truly been left behind. The ambient economic activity is low. There’s a rawness to them, where you sense that human beings are closer to a state of nature. They have their heads down and are just doing whatever it takes to get by.

David Brooks described such towns vividly in a New York Times op-ed:

Today these places are no longer frontier towns, but many of them still exist on the same knife’s edge between traditionalist order and extreme dissolution… Many people in these places tend to see their communities… as an unvarnished struggle for resources—as a tough world, a no-illusions world, a world where conflict is built into the fabric of reality… The sins that can cause the most trouble are not the social sins—injustice, incivility, etc. They are the personal sins—laziness, self-indulgence, drinking, sleeping around. Then as now, chaos is always washing up against the door… the forces of social disruption are visible on every street: the slackers taking advantage of the disability programs, the people popping out babies, the drug users, the spouse abusers.

The folks in New York and San Francisco and Washington, DC, are people who have had layers and layers of extra socialization and institutional training. We are the financiers and technologists and policy professionals who traffic in abstraction. We argue about ideas. Our rents are high and our eyes are set on the next hurdle to climb. We have the luxury of focusing on injustice and incivility.

In small towns and postindustrial communities around the country, they experience humanity in its purer form. Their very family lives have been transformed by automation and the lack of opportunity. Their future will soon be ours.