FIFTEEN

THE SHAPE WE’RE IN/DISINTEGRATION

The progress of a few fortunate decades can too easily be swept away by a few years of trouble.

—RYAN AVENT

The challenges of job loss and technological unemployment are among the most significant faced by our society in history. They are even more daunting than any external enemy because both the enemy and the victims are hard to identify. When a few hundred workers get replaced or a plant closes, the people around them notice and the community suffers. But to the rest of us, each closing is seen as part of economic progress.

The challenges are magnified because American society is not in great shape right now. There are a number of trends that are going to make managing the transition to a new economy all the more difficult:

• We are getting older.

• We don’t have adequate retirement savings.

• We are financially insecure.

• We use a lot of drugs.

• We are not starting new businesses.

• We’re depressed.

• We owe a lot of money, public and private.

• Our education system underperforms.

• Our economy is consolidating around a few mega-powerful firms in our most important industries.

• Our media is fragmented.

• Our social capital is lower.

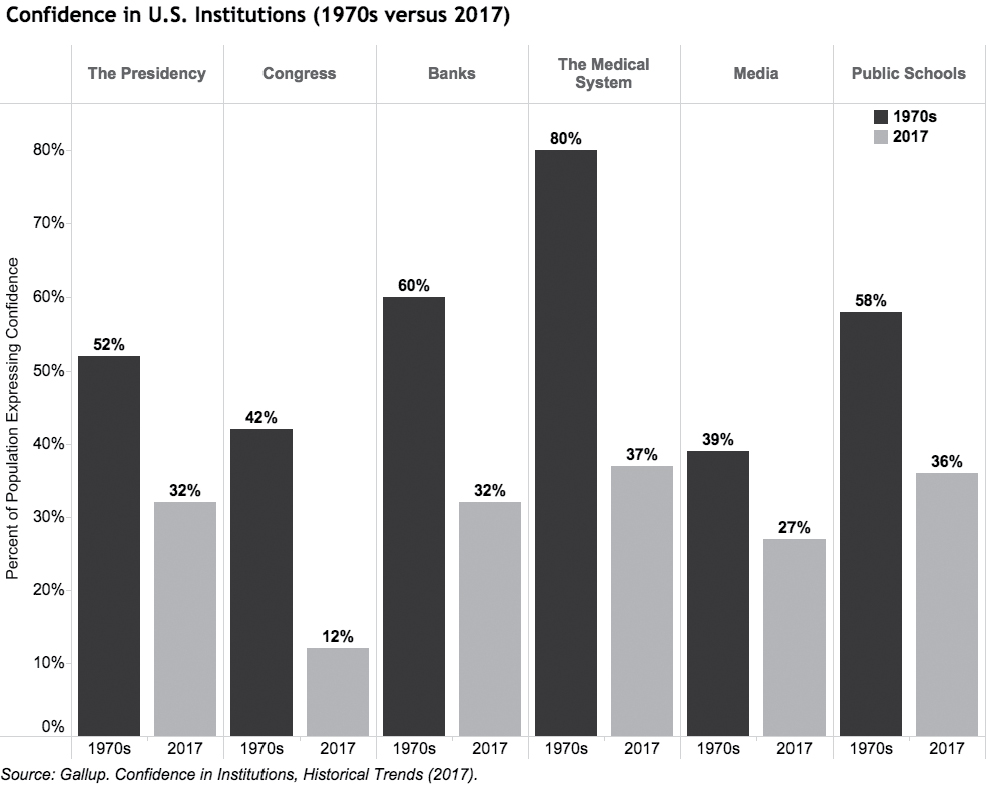

• We don’t trust institutions anymore.

This last one makes everything harder—and it reminds me of my relationship with the Knicks.

I was 15 years old when I became a huge fan of the New York Knicks. I watched the Ewing-led Knicks go up 2-0 on Michael Jordan’s Bulls only to lose the series 4–2. I felt the pain alongside my friends and craved revenge. The Knicks became a part of my life’s fabric, with their deep playoff runs in 1994 and 1999 high-water marks. I would watch every game I could and even listened to games on the radio from my college dorm room. When I moved to New York, I stood in line each year to get nosebleed $10 and $20 seats. After the Knicks became uncompetitive, I gritted my teeth through the Isiah Thomas era and tracked the potential of draftees like Frank Williams and Mike Sweetney.

My love affair turned sour after successive years of turmoil. Not the losing—I totally don’t mind rooting for a team that’s developing young guys and losing competitively. But an endless series of bad behavior and bad decisions began to sour me. What started out as a wholesome sports allegiance felt more and more like an abusive relationship. I couldn’t follow the Knicks anymore. Their leadership was corrupt. Their figures were unsympathetic and incompetent. I swore off the Knicks in 2014 and never looked back.

That’s essentially how many Americans feel about most institutions nowadays. Their love and trust have been taken for granted and abused. Public faith in the medical system, the media, public schools, and government are all at record lows compared to past eras.

We have entered an age of transparency where we can see our institutions and leaders for all of their flaws. Trust is for the gullible. Everything now will be a fight. Appealing to common interests will be all the more difficult.

In the musical Hamilton, the protagonist refers to the newly formed United States as “young, scrappy, and hungry.” That hasn’t been us for quite a while. Membership in organizations like the PTA, the Red Cross, labor unions, and recreational leagues has declined by between 25 and 50 percent since the 1960s. Even time spent on informal socializing and visiting is down by a similar level. Our social capital has been declining for a long time, and there is no sign of a reversal.

All of these things make addressing technological unemployment harder. We no longer believe we’re capable of turning things around without something dramatic changing. Among the things being questioned is our capitalist system. Among young people, polls show a very high degree of sympathy for other types of economies, in part because they’ve witnessed capitalism’s failures and excesses these past years.

I love capitalism—anyone who has a smartphone in their pocket has to appreciate the power of markets to drive value and innovation. We all have capitalism to thank for most of what we enjoy. It has elevated the standard of living of billions of people and defined our society for the better.

That said, capitalism, with the assistance of technology, is about to turn on normal people. Capital and efficiency will prefer robots, software, AI, and machines to people more and more. Capitalism is like our mentor and guiding light, to whom we’ve listened for years. He helped us make great decisions for a long time. But at some point he got older, teamed up with his friend technology, and together they became more extreme. They started saying things like, “Ah, let’s automate everything” and “If the market doesn’t like it, get rid of it,” which made reasonable people increasingly nervous.

Even the most hard-nosed businessperson should recognize that the gains and losses from unprecedented technological advances will have dramatic sets of human winners and losers, and that the system needs to account for that in order to continue. Capitalism doesn’t work that well if people don’t have any money to buy things or if communities are degenerating into scarcity, anger, and despair.

The question is, what is to be done?

If we do nothing, society will become dramatically bifurcated on levels we can scarcely imagine. There will be a shrinking number of affluent people in a handful of megacities and those who cut their hair and take care of their children. There will also be enormous numbers of increasingly destitute and displaced people in decaying towns around the country that the trucks drive past without stopping. Some of my friends project a violent revolution if this picture comes to pass. History would suggest that this is exactly what will happen.

America has been getting less violent in most measurable ways—violent crimes and protests are all less common than in the past, even though it doesn’t seem like it. For example, there were approximately 2,500 leftist bombings in America between 1971 and 1972, which would seem unfathomable today. It’s possible that we may already be too defeated and opiated by the market to mount a revolution. We might just settle for making hateful comments online and watching endless YouTube videos with only the occasional flare-up of violence amid many quiet suicides.

Yet, it’s almost certain that increasing levels of desperation will lead to destabilization. One can imagine a single well-publicized kidnapping or random heinous act against a child of the privileged class leading to bodyguards, bulletproof cars, embedded safety chips in children, and other measures. The rich people I know tend to be somewhat paranoid about their own safety and that of their families. To me, without dramatic change, the best-case scenario is a hyper-stratified society like something out of The Hunger Games or Guatemala with an occasional mass shooting. The worst case is widespread despair, violence, and the utter collapse of our society and economy.

This viewpoint may strike some as extreme. Consider, though, that trucking protests were common in the final days of the Soviet Union, a large unemployed group of working-age men is a common feature in Middle Eastern countries that experience political upheaval, and there are approximately 270 to 310 million firearms in the United States, almost one per human being. We are the most heavily armed society in the history of mankind—disintegration is unlikely to be gentle. The unemployment rate at the height of the Great Depression was about 25 percent. Society experiences fractures well before all the jobs disappear.

In his book Ages of Discord, the scholar Peter Turchin proposes a structural-demographic theory of political instability based on societies throughout history. He suggests that there are three main preconditions to revolution: (1) elite oversupply and disunity, (2) popular misery based on falling living standards, and (3) a state in fiscal crisis. He uses a host of variables to measure these conditions, including real wages, marital trends, proportion of children in two-parent households, minimum wage, wealth distribution, college tuition, average height, oversupply of lawyers, political polarization, income tax on the wealthy, visits to national monuments, trust in government, and other factors. Turchin points out that societies generally experience extended periods of integration and prosperity followed by periods of inequity, increasing misery and political instability that lead to disintegration, and that we’re in the midst of the latter. Most of the variables that he measures began trending negatively between 1965 and 1980 and are now reaching near-crisis levels. By his analysis, “the US right now has much in common with the Antebellum 1850s [before the Civil War] and, more surprisingly, with… France on the eve of the French Revolution.” He projects increased turmoil through 2020 and warns that “we are rapidly approaching a historical cusp at which American society will be particularly vulnerable to violent upheaval.”

If there is a revolution, it is likely to be born of race and identity with automation-driven economics as the underlying force. A highly disproportionate number of the people at the top will be educated whites, Jews, and Asians. America is projected to become majority minority by 2045. African Americans and Latinos will almost certainly make up a disproportionate number of the less privileged in the wake of automation, as they currently enjoy lower levels of wealth and education. Racial inequality will become all the more jarring as the new majority remains on the outside. Gender inequality, too, will become more stark, with women comprising the clear majority of college graduates yet still underrepresented in many environments. Less privileged whites may be more likely to blame people of color, immigrants, or shifting cultural norms for their diminishing stature and shattered communities than they will automation and the capitalist system. Culture wars will be proxy wars for the economic backdrop.

This is already happening. Alec Ross, an author and Baltimore resident, described the Freddie Gray riots in 2015 as partially a product of economic despair. The protests injured 20 police officers, resulted in 250 arrests, damaged 300 businesses, caused 150 vehicle fires and 60 structure fires, and led to the looting of 27 drugstores. “While the triggering event [of the riots] was the death of a 25-year-old man in police custody, the protesters themselves consistently rooted their cause and rallying cry… in more than police brutality. It was about the hopelessness that came from growing up poor and black in a community that had been laid to waste with the loss of Baltimore’s industrial and manufacturing base and then gone ignored. Black working-class families had effectively been globalized and automated out of jobs.” The Charlottesville violence in 2017 over the removal of Confederate symbols can also be seen as engendered in part by economic dislocation. The driver of the car that plowed into the crowd, killing a young woman, was from an economically depressed part of Ohio and had washed out of the military. James Hodgkinson, the liberal activist who shot four people and critically wounded a congressman at a softball game in 2017, was a 66-year-old unemployed house inspector from Illinois whose marriage and finances were failing.

The group I worry about most is poor whites. Even now, people of color report higher levels of optimism than poor whites, despite worse economic circumstances. It’s difficult to go from feeling like the pillar of one’s society to feeling like an afterthought or failure. There is a strong heritage of military service in many white communities that will be subverted into antigovernment militias, white nationalist gangs, and bunkers in the woods. There will be more random mass shootings in the months ahead as middle-aged white men self-destruct and feel that life has no meaning. As the mindset of scarcity spreads and deepens, people’s executive functioning will erode. It takes self-control to resist base impulses. Racism and misogyny will become more and more pervasive even as it is policed in certain sectors.

Contributing to the discord will be a climate that equates opposing ideas or speech to violence and hate. Righteousness can fuel abhorrent behavior, and many react with a shocking level of vitriol and contempt for conflicting viewpoints and the people who hold them. Hatred is easy, as is condemnation. Addressing the conditions that breed hatred is very hard. As more communities experience the same phenomena the catalysts will be varied and the reactions intense. Attacking other people will be a lot easier than attacking the system.

Could extreme behavior in some places even precede a political breakup of the country? One can imagine California, the most racially diverse, progressive, and wealthy state, holding a referendum to secede in response to events elsewhere in the country that are perceived as atavistic and regressive. There is already a nascent movement among technologists, libertarians, and others in California to secede on economic grounds, including the recent “Yes California” movement pushing “Calexit” and the California National Party—about one-third of Californians supported secession in a recent poll, up considerably from earlier levels. California would be the sixth-largest economy in the world as a separate country. If there were a successful vote, two-thirds of Congress and three-quarters of states would be required to approve it under the Constitution, which today seems impossible. However, California’s departure would permanently tilt the country’s political balance, which could be appealing to the party in power. Such a vote could also prompt a reprisal or punishment. Texas likewise has a long history of secessionist movements.

Earlier I wrote about truck drivers, who will soon start to lose their jobs or have their wages reduced as automated trucks enter the market. Let’s imagine that one of them, Mike, owns a small trucking company with 10 trucks and 30 drivers. He sees his life savings about to go down the tubes because he owes the banks hundreds of thousands of dollars in loans he took out to buy his vehicles. Mike says to his guys, “Fuck this. We can’t be replaced by robot trucks. Let’s go to Springfield and demand our jobs back.” He leads a protest in Illinois and hundreds of truckers join in, some of them bringing their vehicles and blocking roads. The police respond but they are reluctant to use force. The crowds multiply as more drivers and rioters arrive.

Inspired by what they see on social media, truckers begin to protest in other state capitals in the tens of thousands. The National Guard is activated and the president calls for calm, but disorder grows. Various antigovernment militias and white nationalist groups say, “This is our chance,” and arrive in each state to support the truckers. Some of them bring various weapons, and violence breaks out. The protests and violence spread to the capitals of Alabama, Arkansas, Idaho, Indiana, Kentucky, Mississippi, Michigan, Ohio, and Nebraska. Locals take advantage of police preoccupation in these areas and begin looting drugstores nearby.

The president calls for a return to order and says that he will meet with the truckers. However, the protests morph into many distinct conflicts with unclear demands and fragmented leadership. Mike is held up as a symbol of the working man but has no control. The riots rage for several weeks. In the aftermath, there are dozens dead, hundreds injured and arrested, and billions of dollars’ worth of property damage and economic harm. Images of the violence spread on the Internet and are seen by millions in real time.

After the riots, things continue to deteriorate. Hundreds of thousands stop paying taxes because they refuse to support a government that “killed the working man.” A man in a bunker surrounded by dozens of guns releases a video saying, “Come and get your taxes, IRS man!” that goes viral. Anti-Semitic violence breaks out targeting those who “own the robots.” A white nationalist party arises that openly advocates “returning America to its roots” and “traditional gender roles” and wins several state races in the South. Graffiti and literature for the new party appear on college campuses, which leads to protests and sit-ins. A shooter arrives in the lobby of a technology company in San Francisco and wounds several people. Technology companies hire security forces, but 30 percent of employees request to work remotely due to a sense of fear. Several tech companies move to Vancouver, citing a desire for employee safety. The California secession movement surges as state officials move to protect the border and implement checkpoints.

Maybe the scenario I sketched above seems unlikely. To me, it seems depressingly plausible. But this vision assumes that we keep the system as it is right now, where we prioritize capital efficiency above all and see people primarily as economic inputs. The market will continue to drive us in specific directions that will lead to extremes even as opportunities diminish at every turn.

Forestalling automation and retaining jobs might help. Some would argue we should require that a human is in every truck, only let doctors look at radiology films, and maintain employment levels in fast food restaurants and call centers. However, it would be nearly impossible to curb automation for any prolonged period of time effectively across all industries. The result would be that certain workers and industries would be protected while others in an industry that is less core—like retail—would be quickly displaced.

This reminds me of a story the economist Milton Friedman told about visiting a Chinese worksite. He notices that there are no big tractors or pieces of equipment, only men with shovels. He asks his guide, “Where are all of the machines to dig the holes and move the earth?”

His guide responds, “You don’t understand. This is a program designed to create jobs.”

Milton thinks for a second, then asks: “So why give them shovels?”

Time only flows in one direction, and progress is a good thing as long as its benefits are shared.

Doing nothing leads to almost certain ruin. Trying to forestall progress is likely a doomed strategy over time.

What’s left?

When you’re left with no other options, the unthinkable becomes necessary. We must change and reformat the economy and society to progress through a massive historical shift. Much of this book has likely come across as quite negative. This transition will indeed be very difficult. But the opportunities ahead are vast.

Robert Kennedy famously said that GDP “does not allow for the health of our children, the quality of their education, or the joy of their play… it measures everything, in short, except that which makes life worthwhile.” We have to start thinking more about what makes life worthwhile.