MEN’S CLOTHING OF THE PERIOD was conservative, and with Edwardian times being predominantly class structured, the clothing worn reflected social class. Gradually, civilian clothes would give way to military and naval uniforms. However, photographs showing the recruitment crazes of 1914 at the recruiting offices reveal a mingling of all social classes, with everyone clad typically in three-piece suits, and topped off with a hat of some kind. Waistcoats were common to all, and jacket lapels were fastened quite high, rather than displaying much of the shirt and waistcoat. Hardwearing and well-cleated boots were worn by most.

In general terms, men of working-class background were more likely to be clad in rather more shapeless suits than those from middle-class backgrounds. Suits were worn on all occasions, from the workplace to the pub. Large flat caps were usually worn, sometimes of incredible dimensions; it was rare for a man to be seen without a hat. Middle-class suits were better cut, with slimmer lines, and closer-fitting trousers tapering to turn-ups, usually worn with well-polished shoes. This is the classic image of the well-to-do young ‘knut’ – a gadabout, a person often accused of being a shirker. The term ‘knut’ was personified in the 1914 hit song: ‘I’m Gilbert the Filbert, the knut with a k. The pride of Piccadilly, the blasé roué’. Such men would wear shirts with high, detachable collars with rounded edges and ties. Waistcoats would be worn with Albert chains and pocket watches, often adorned by fobs. Wristwatches were less common in prewar times, and were considered effeminate; yet during the war they became a phenomenon, with ‘wristlets’ being worn by officers and men alike. Hats worn by the middle classes varied from a better-quality flat cap through to a boater, with bowler hats and other varieties being worn to the workplace. For those with more disposable income there would be more variety: formal suits and wing collars, waistcoats with white edging, cravats and cravat pins, and, for country wear, tweed Norfolk jackets worn with plus-fours. Dressing for dinner, in formal dinner suits, was also common in upper-class households.

A typical ‘knut’, the man about town, with cane, gloves and boater. Such men would be the target of women distributing white feathers.

On War Service badges were introduced for civilian workers in 1914. As the war progressed, there was increasing pressure by the government to ‘comb out’ skilled civilians for the armed services, by the process of ‘debadging’.

From 1914 onwards, men employed at home on war service were issued with official badges that were worn with civilian dress, intended to protect them from the Order of the White Feather. Cloth armlets bearing official designations were also common; from 1915 the khaki serge armlet with red crown signified that the wearer had attested under the short-lived Derby Scheme. As the war dragged on, the number of silver war badges seen on suit lapels grew. Worn by wounded, honourably discharged soldiers and sailors, this badge was again intended to defend the wearer from the white feather. Uniforms became more commonly seen on the streets; men would return home from the front bearing the mud of Flanders on their clothing; officers would wear their service-dress uniforms patched and reinforced like comfortable jackets.

Silver war badge (SWB), issued to all men wounded and discharged. As with the ‘On War Service’ badges, the SWB was intended to protect its wearer from the white feather.

Uniforms became de rigeur, so much so that wives and sweethearts of those serving would be photographed ‘larking about’ in the uniforms of their men. When the men in question returned to the front, the women – mothers, sisters, sweethearts, wives – would wear a remembrance of their men, often a simple regimental brooch, commercially produced in their thousands, or even, commonly, a badge created by the soldier from his regimental insignia. The richest examples were gold with jewels; the simplest, perhaps a button with brooch fitting.

Women’s clothing, like that for men, was restricted according to class – a function of spending power and the exigencies of the working-class lifestyle. In the upper echelons, women’s clothing, then as now, was directly influenced by the fashionable elite. For those with disposable income, the most desirable styles created a silhouette with a high waistline, just under the bust, echoing the ‘Empire’ styles of the early nineteenth century. Tunics were commonly worn over long, ankle-length skirts, worn over an underskirt of similar length. Shoes were slim in style and had a high heel, often worn with a short gaiter. Large hats were very much in evidence, with a broad brim in the early stages of the war, though shrinking to a much more manageable style by its end, matching the fashion for short, bobbed hairstyles that would continue into the post-war era.

A young woman poses for the camera in summer clothes with fashionably long skirt, c. 1914. The length of women’s skirts would shorten as the war progressed.

Fashions worn by the elite were not always practical; at the outbreak of war the rich developed a penchant for the so-called ‘hobble’ skirt, widest at the hips and reducing to a very narrow width at the ankle. Walking any great distance in these garments was impossible; this style would not last into the more practical times of the war. Other elements of high fashion included the adoption of ‘orientalism’, with flowing ‘harem’ pantaloons and turbans. By the middle years of the war, however, dressing in high fashion was considered not to be ‘the done thing’, unpatriotic at a time of national emergency (and the subject of a poster campaign by the War Savings Committee). Suits of matching jacket and skirt also became common during the war, and were worn by all who could afford them, usually set off by a hat that varied in grandeur depending on the spending power of the purchaser. For working-class women the staple of the long skirt and tunic top mirrored that of the more extravagant classes. Large hats were also in vogue, but plainer in style.

As the war developed, so did the well-to-do women’s silhouette. The high waistline of the pre-war years now slipped down to a more natural position at the actual waist, and tunics lengthened to match the change. By contrast, skirts shortened, raised off the ankle to the calf, creating a much more practical daywear, and cumbersome underskirts were largely lost. Hats became much less extravagant, and colours were toned down, monochromes being more in keeping with the mood of the nation, particularly when families were mourning the loss of loved ones. Costume jewellery was also introduced at this time, an indication of the need to dress in line with wartime expectations.

With women entering the workplace in large numbers during the war, clothing became practical and utilitarian. The ‘munitionettes’ wore a simple wrap-around overall and a hat designed to keep their hair well out of their eyes – and well away from machinery. Distinctive triangular ‘On War Service’ badges were worn with this clothing. Shoes were necessarily utilitarian, laced and low-heeled. For some occupations there was a uniform – usually with a long skirt commonly worn with a long coat, jacket and hat. Such styles were adopted for roles as diverse as bus conductresses and women police officers. Perhaps the most dramatic change was the adoption of breeches by women in some roles, in the Women’s Land Army, for example.

A wartime family, c. 1916. The two women wear simple skirts and blouses. Military badges of friends and relatives are worn, with the crossed machine guns of the Machine Gun Corps. The boy wears the uniform of a cadet of the King’s Royal Rifle Corps.

Munitions worker from a national projectile factory, showing the simple but effective uniform.

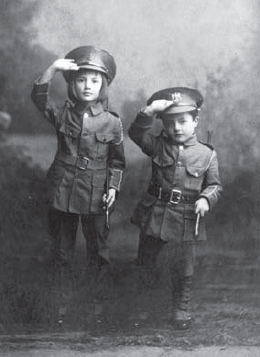

Children as adults – dressed up as soldiers.

For children, clothes more or less mirrored that of the parents, particularly for working-class children. Boys were dressed in suits, though with short trousers, and often with stiff collars and boots. Girls’ dresses were more child-friendly, but again echoed those of their mothers, and were also worn with boots. Sailor suits for both sexes were common – and miniature military costumes made their way into the household. Postcards of children wearing these outfits are common, and in some ways a poignant reminder that the war was to touch the lives of absolutely everyone. For poorer households, choice was limited – and children wore whatever clothes were available.

By 1918, shortages of raw materials – from both the U-boat campaign and the ever-increasing demand for wool for military uniforms – meant that the supply of clothing was severely curtailed. Austerity was patriotic, and, for the rich or well off, unnecessary frills and flourishes were no longer seen on new clothes. For poorer folk, the cost of clothing had risen far beyond their means, even given the increase in disposable income enjoyed by some households; this led to the introduction of a system of standard clothing in June 1918 (the precedent for similar ‘austerity’ schemes re-introduced to Britain in the Second World War), whereby the textile industries were to produce materials that could be sold to produce fixed-price clothing. For men, standard suits cost between 84s and 57s 6d, overcoats were set at 63s; the children’s equivalents were 45s and 35s respectively. Ever present, the War Savings Committee was to sponsor an attitude of austerity as the war came to its conclusion, which would stagger on into the peacetime world.

Soldiers in full uniform and kit – and often covered with Flanders mud – were common on the nation’s rail system. Donald McGill postcard.