TRANSPORT had taken great strides during the Edwardian boom-time, advances that would stand Britain in good stead during the First World War. In London in particular, the idea of commuting to a place of work became a familiar reality, particularly with the increasing prevalence of buses, trams and underground railways that began in the mid-nineteenth century.

Though underground railways were relatively rare outside London (Glasgow and Liverpool being exceptions), the other transport options were repeated up and down the country. In all cases, the Victorian street scene of horse-drawn transportation would be replaced by one in which electricity, and the internal combustion engine, were dominant. The first electric tramway came to the streets of Blackpool in 1885 (the first street tram in Europe having appeared in Birkenhead in 1860), and would spread to the rest of the county, its criss-crossing overhead wires and sunken rails a common sight in many city streets. The first electric tramway in London followed in July 1901. From late 1915, there was a new circumstance. Women staff started to appear on the trams, but not without resistance in some male quarters. Female tram drivers were in a minority, even as the war progressed to its conclusion, though women conductors, whose job it was to issue and check tickets, became a familiar sight across Britain from 1916. There would be some 117,000 women working in the transport industry by 1918.

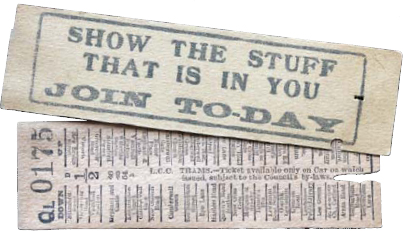

Tram tickets from south London; every opportunity was taken to persuade men to join the army.

‘Doing her bit’. Children were popular subjects for wartime postcards, particularly children mimicking the duties of adults – in this case women bus and tram conductors.

Motorised omnibuses would make an appearance in Britain in 1905 and became very popular: while in 1907 only 1,205 of the 3,762 licensed buses on the streets of London were motorised, by the outbreak of war 2,908 of the 3,284 licensed buses were motor-powered. Buses and trams would carry the majority of people from their new suburbs to their places of work in the heart of the great cities – and would provide a means of servicing Britain’s industrial heart with workers. In London, tens of thousands would travel by bus each day, and, just as with the tramways, the buses would be staffed by female conductors. Here, though, there would be no women drivers. This pattern would be replicated in other British cities.

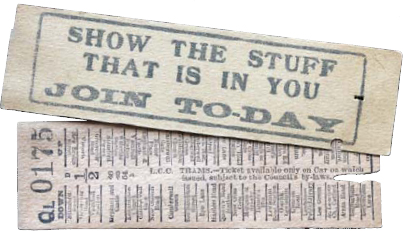

Motor-car advert, c. 1916. There was a proliferation of car manufacturers and types available to the prospective buyer.

But with crashing gears and engine noise came the crush of the private motor car. First appearing in any numbers during early Edwardian times (with the first case of manslaughter by reckless driving tried at the Old Bailey in 1906), the car would come to dominate the street scene in Britain. The Motor Car Act of 1903 raised the speed limit on Britain’s city streets from 14 mph to a staggering 20 mph, and required that every driver was issued with a licence to drive by the local authorities, with the minimum driving age being set at seventeen. What was not required, however, was a driving test, though the crime of ‘reckless driving’ was also introduced as a counter to poor roadmanship. Motor vehicles also had to be registered, and the registration number displayed clearly upon the car. A branch of the Volunteer Training Corps – a volunteer organisation in many ways akin to the Home Guard of the Second World War – would be styled the National Motor Volunteers, and would comprise men with cars who volunteered to be of service to the nation.

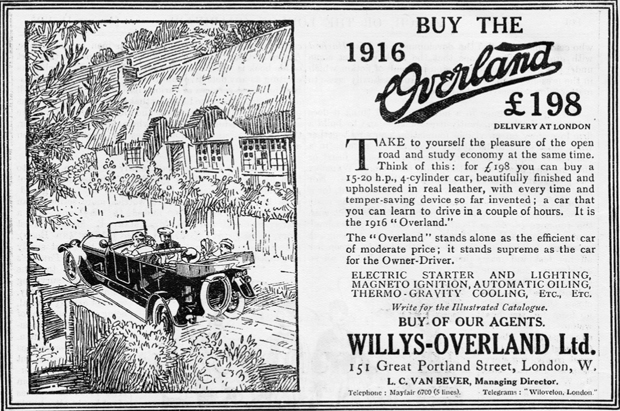

Street scene in London, 1918, as depicted by a shoe manufacturer. Motor omnibuses and cars had long since replaced horse-drawn vehicles.

With the coming of the petrol engine came the traffic jam – particularly in the years just prior to the war when there was a decided shift from the railways to the automobile. With the Model T popular on both sides of the Atlantic from 1909, a new assembly plant opened in Manchester in 1911, followed by the installation of an automated production line two years later, allowing 6,000 cars a year to be produced, each bought at a cost of £135. There were many other manufacturers. It is not surprising that, a year before the outbreak of war, it was estimated that over 90 per cent of all passenger vehicles in London were motorised. With London’s streets clogged with traffic, and commuting now common, it is little wonder that there was increased demand for the underground railways during this time.

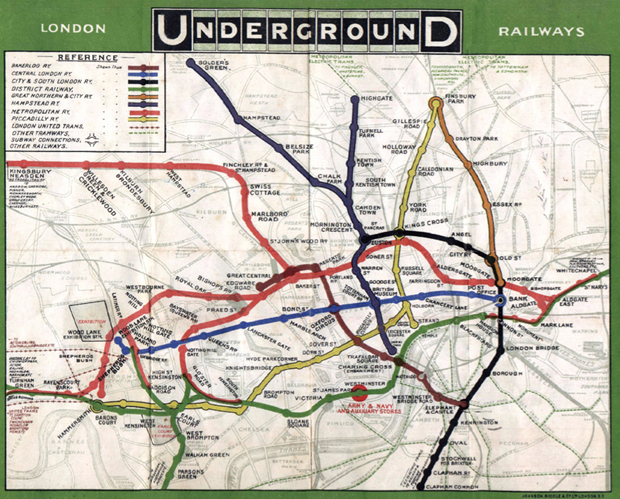

London had operated an electric underground railway since 1890 (the ‘subway’ in Glasgow was operated from 1896), with the opening of the City and South London Railway, and by 1900 the number of railway companies offering underground services to the capital had multiplied. The Central London Railway was opened in this year, and with its cylindrical tunnel system had become known as the ‘two-penny tube’, a name that would be adopted by all ‘tube’ lines later. In all there would be eight independent ‘tube’ operators. In an effort to promote their services, the companies used the name ‘Underground’ from 1908, and introduced the now-familiar ‘roundel and bar’ logo in 1913 as the standard symbol of the combined system. In the prelude to the war, and during the war itself, the combined underground system continued to grow, electrifying lines and expanding out to the suburbs, with ever more demand for its services as the wartime population of London swelled, during the day at least.

The London Underground in 1908, when the independent lines were brought together in an attempt to promote the service. The distinctive ‘roundel and bar’ would be adopted in 1913.

The underground also served another purpose for the people of London; with no air-raid shelters as such, and no real coordination of ‘air-raid precautions,’ the arrival of the Zeppelins in 1915 and Gotha bombers in 1917 saw underground stations used for shelter, with at least 300,000 people in the city taking to the underground. This experience would be repeated in 1940 – with less approval. Elsewhere, railway viaducts, tunnels and caves would serve the same purpose.

National railways passed into state control on 4 August 1914, on the eve of war. The government had held the power to do this since 1871, and had enacted it in order to ensure the efficient transfer of men and materiel throughout Britain in the time of war. The effect of the act was ‘to coordinate the demands of the railways of the civil community with those necessary to meet the special requirements of the naval and military authorities’. With 120 rail-operating companies across Britain, this was very necessary. The movement of rail freight and passengers passed to the War Railway Council, staffed by military representatives and members of the Board of Trade. There were a large number of ‘special’ trains – mostly carrying troops. The longest was soon nicknamed ‘The Misery’. Carrying naval personnel from London to Thurso (in order to man the Grand Fleet at Scapa Flow), the journey was some 728 miles and took over twenty-two hours.

Rail stations were scenes of great activity and heartbreak. Troop trains from the south coast into the London termini would be packed with soldiers returning on leave, their uniforms begrimed with mud from the trenches, their weapons and equipment stowed in luggage racks. Trains would arrive bearing severely wounded soldiers en route to hospitals, their off-loading a flurry of activity with nurses and medical staff. Departing trains would be bearing men back to France, their loved ones suffering the agony of parting. In the midst of all this, private passengers could travel, but the opportunity for them to do so was severely curtailed – particularly as cheap tickets were withdrawn in spring 1915. Rail companies now no longer ‘touted for business’; the railways were on a war footing.

With the rail system dominated by the transport of men and materiel throughout the country, it was perhaps inevitable that the system – and its operators – would be pushed to breaking point. Perhaps because of these circumstances, the worst rail disaster in British history was to occur on 22 May 1915 near Gretna Green in Scotland. This crash took place at a busy junction with sidings at Qunitinshill, and involved five trains. A signalman had shunted a local train onto the ‘up’ line in order to let two express trains pass on the ‘down’ line; a troop train ran into the waiting local train and one of the express trains also ran into the wreckage. The wooden-framed and -panelled gas-lit carriages of the troop train were engulfed by fire. The crash caused the deaths of 226 people – most of them soldiers of the 7th Battalion Royal Scots on their way to the Dardanelles – with some 246 others injured. Of the 500-strong battalion, just fifty-seven men were present at roll call that afternoon.

Engine from the London and North Western Railway in the pre-war period. The LNWR considered itself to be the most important of all railway lines during the period, and served all the major industrial cities of late Edwardian Britain. It would fall under War Office control during the war.

‘Tommy’, a song from the musical revue, The Better ’Ole, which opened at the Oxford Theatre in London in 1917.