Wood

The rainforest: a dense green mass of vegetation, difficult to be in, even harder to work in. Where to start? Surely one patch of jungle is much like any other? Everything is up close, in your face, dripping and slimy, there are no sweeping views, and the light is awful. But anyone who has spent time in rainforests knows what fascinating places they are – full of life, the lungs of the planet: I always feel privileged to be there. It’s an environment that assaults the senses; the sounds and smells of the jungle permeate my soul. And they are all different. Definitely difficult to photograph, but no one ever said this game was easy.

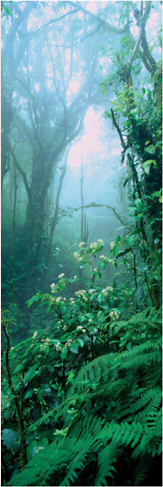

Monteverde Cloud Forest Reserve, Costa Rica

With the light levels fluctuating widely as the clouds filtered through the trees, exposing for this shot was murder. Halfway through a five-minute exposure the sun penetrated the mist, sending light levels and contrast through the roof. I aborted the exposure and started another. I shot two rolls of 220 just to get one perfect exposure.

• Fuji GX617, 90mm lens

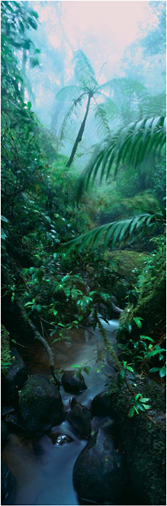

Waterfall with wild Busy Lizzies (Impatiens) near Alajuela, Central Valley, Costa Rica

It’s often difficult in the rainforest to see any colour other than green. Here by the waterfall these Busy Lizzies give a splash of pink to offset the cool blues and greens deep in a jungle valley.

• Fuji GX617, 90mm lens

Monteverde Cloud Forest Reserve, Costa Rica

The mists passing through the forest gave an ethereal mood and a lovely low-contrast light, perfect for this environment. It also meant everything was permanently moist, the vegetation, the air, the camera and me. Keeping the drips off all the gear was a major undertaking.

• Fuji GX617, 180mm lens

“Light levels are very low, think in terms of exposures of minutes, so don’t even consider going without a tripod”

As usual, location searching is the key, and that means getting the boots on. Finding a strong composition is the goal; it’s a case of tuning your photographic vision into the fine details of the rainforest. I look for visually strong features to base a composition on, such as roots, vines, streams or some graphic detail. Lighting is the other big issue, but here under the dense jungle canopy all the previously held notions of what light I like for landscape work are redundant. Strong directional sunlight is definitely what I do not need: the contrast goes through the roof, or rather canopy, resulting in burnt-out highlights and dense black shadows. Leaden grey skies giving a flat, diffuse top lighting are perfect. Light levels are very low: think in terms of exposures of minutes, so don’t even consider going without a tripod.

Giant cedar tree, Meares Island, Clayoquot Sound, Vancouver Island, British Columbia, Canada

Not all rainforests are tropical. Here on Meares Island the giant cedar trees that used to be found all over Vancouver Island are truly majestic. How can anyone contemplate cutting down one of these ancient living entities? This one would have been a sapling when the Romans ruled supreme. I can’t include the entire towering giant in the frame so I concentrate on showing its girth in relation to the new growth around it.

• Fuji GX617, 105mm lens

Buttress roots on tree, tropical rainforest, Daintree, Queensland, Australia

The roots of a tree in the tropical rainforest reminded me of the flying buttresses on Gloucester Cathedral. I suppose they’re similarly supportive in the thin soil.

• Fuji GX617, 105mm lens / Nikon F5, 16mm fisheye lens

Fill-in flash can be effective for lighting details. And take an empty film canister full of salt. It’s for the leeches you see: if you find any of these blood-suckers clinging to your anatomy just pour salt on and they shrivel and drop off. An umbrella is also useful as, funnily enough, it often rains in tropical rainforests, and I mean seriously rains. It’s far too hot to wear a jacket and under an umbrella you can continue shooting. Being a bit of a control freak I usually resist being led anywhere by the hand, but there’s no substitute for local knowledge, so a guide can provide a fascinating insight into the complex ecosystem. Above all, stop, look and listen. Let the jungle envelop you in its mystery. It’s far too easy to trudge past things of interest.

Westland National Park, South Island, New Zealand

At the foot of Fox Glacier in New Zealand’s Westland National Park lie tracts of dense temperate rainforest. It seems a bizarre mix: ice and dense greenery. Temperate rainforests have a very different feel to their tropical counterparts – they’re much more mossy. In fact the more time you spend in the woods the more you realize all forests are different.

• Fuji GX617, 90mm lens

Santa Elena Cloud Forest Reserve, Costa Rica

The mud gets everywhere. I’m wearing a plastic poncho, but it’s hopeless; nothing stays dry in here. It’s an ethereal place, everything is draped in moss, the cloud hangs amongst the trees, it’s dark, damp and muddy, and we love it. After a few days of this everything we own is covered in a thin layer of rainforest slime. The damp mists are swirling all around us, the leaves are constantly dripping, and as we brush through the undergrowth they shed more soggy delights on us just for good measure. The trail is a slippery quagmire that we slosh and slide along like inebriated ice skaters. Welcome to the cloud forests of Costa Rica.

The spine of mountains that to the north constitute the Rockies, and to the south the Andes, crosses the narrow isthmus of Central America as a 6,500ft jungle-clad ridge. The warm air from the Caribbean streams over this ridge en route to the Pacific, cooling as it does and forming dense damp clouds filtering through the woods; this is a cloud forest and it’s a first for me. We’re spending four days here tramping the forest trails in search of the definitive images of this unique ecosystem, and despite the grime it’s great fun.

Photographing the cloud forest presents some serious challenges. The damp and the mud is an inconvenience to us but if it gets into my kit all sorts of bad things will happen. Every day we trudge thorough the forest in search of strong compositions among the seemingly impenetrable mass of vegetation. As it turns out there’s a wealth of potential once you get your eye tuned in.

The mud squelches beneath our feet, I stop and look. There’s a shot here. Wendy releases the plastic sheet from the back of my Lowepro and lays it in the mud for the bag to rest on. I erect the tripod; Wendy then holds an umbrella over the bag as I rummage inside. Drips run down my neck but the

“Every day we trudge thorough the forest in search of strong compositions amongst the seemingly impenetrable mass of vegetation. As it turns out there’s a wealth of potential once you get your eye tuned in”

kit is protected. We’re working as a welloiled machine now after days of this. I transfer the camera to the tripod under the brolly; I’m using the panoramic camera vertically. I spot meter off a leaf in the foreground, open the shutter and start the long wait. With a polarizer on to saturate the colours in the vegetation, at f/45 the exposure time is eight minutes. As the feeble light does its work on the silver halide crystals we watch the mists swirling through the lush canopy above – it’s incredibly atmospheric. The sounds of the forest envelope us, we are not alone, that’s for sure. A jaguar could be within spitting distance and we’d never know it.

After four minutes I take another reading. The light levels are fluctuating as the cloud blows through the trees; it’s half a stop brighter now. I end up giving it six minutes and start another exposure, and so on. I get off just eight frames in an hour. I don’t feel it’s enough, allowing for bracketed exposures and the varying amounts of mist. I reload and start on another exposure. Occasionally the sun briefly penetrates the mists in the upper canopy, sending the contrast sky high and forcing me to abort the exposure. Generally though, the flat low-contrast light predominates.

Trudging back, bag heavy on my back, muddy, soggy, exhausted. Images have been made though, and that always engenders a deep-seated feeling of satisfaction. We descend into the bright tropical sunshine of late afternoon. Below and to the west lies the Bay of Nicoya and the Pacific coast, our next destination: palm trees, beaches and sunshine.