INTRODUCTION

What is Brooklyn that thou art mindful of her?

—PSALM 8:4, MODIFIED

This book is about the shaping of Brooklyn’s extraordinary urban landscape. Its focus is not the celebrated sites and landmarks of the tourist map, though many of those appear, but rather the Brooklyn unknown, overlooked, and unheralded—the quotidian city taken for granted or long ago blotted out by time and tide. In the pages that follow I hope to breathe fresh life into lost and forgotten chapters of Brooklyn’s urban past, to shed light on the visions, ideals, and forces of creative destruction that have forged the city we know today. Spanning five hundred years of history, the book’s scope encompasses the built as well as unbuilt, the noble and the sham, triumphs as well as failures—dashed dreams and stillborn schemes and plans that never had a chance. The book casts new light on a place as overexposed as it is understudied. It is not a comprehensive history, nor one driven by a grand thesis, but rather a telling that plaits key strands of Brooklyn’s past into a narrative about the once and future city. It is a recovery operation of sorts, a cabinet-of-curiosities tour of the Brooklyn obscure, of the city before gentrification and global fame—that “mythical dominion,” as Truman Capote put it, “against whose shore the Coney Island sea laps a wintry lament.”

THE QUIVERING CHAIN

Brooklyn may be a brand known around the world, but it is also terra incognita—a terrain long lost in the thermonuclear glow of Manhattan, possibly the most navel-gazed city in the world outside of Rome and the subject of dozens of good books. With some exceptions—the Brooklyn Bridge, Coney Island, the gentrification of Brownstone Brooklyn, and the grassroots struggles to fight poverty and discrimination in Bedford-Stuyvesant and East New York—the story of Brooklyn’s urban landscape remains largely untold, the subject of only a handful of texts beyond the usual guidebooks and nostalgia-laden compendia of old photographs.1 Little or nothing has been written about how Gravesend was the first town planned by a woman in America; how Green-Wood Cemetery was not only a place of burial but effectively New York’s first great public park; how Ocean Parkway fused a Yankee pastoral idea to boulevard design lifted from Second Empire Paris to create America’s greatest “Elm Street”; about how the long-vanished Sheepshead Bay Racetrack became the toast of the thoroughbred world, birthplace of the “Big Apple,” and later the launching point of the first airplane flight across the United States; or about how Marine Park was nearly chosen as the site for what ultimately became the 1939 New York World’s Fair. We know equally little about the rise and fall of Floyd Bennett Field, New York’s first municipal airport and the most technically advanced airfield in the world when it opened; or about the thirty-year political tug-of-war that nearly made Jamaica Bay the world’s largest deepwater seaport (complete with the earliest known proposal for containerized shipping); or how a long-forgotten piece of 1920s tax legislation unleashed the greatest residential building boom in American history, one that churned Brooklyn’s vast southern hemisphere—much of it farmed since the 1630s—into a dominion of mock-Tudor and Dutch-colonial homes; or the vast urban renewal and expressway projects that Robert Moses unleashed on Brooklyn after World War II, the largest, most ambitious, and most devastating in the United States. All of these are among the subjects of this book.

If this work is about the “onetime futures of past generations,” to quote Reinhart Koselleck, it is also about the city today. For the past is a dark moon that tugs at our orbital plane, moving it in barely perceptible ways, exerting—as Pete Hamill has put it—an “almost tidal pull” upon the present and on our lives. The urban landscape has a long memory, an LP record with brick-and-mortar grooves. That which seems long gone is often still about our feet, hidden in plain sight. The urban past is all around us, and it conditions and qualifies the present. The modern city is replete with palimpsests and pentimenti, stubborn stains and traces of what went before, keepsakes that beckon us to unpack and explore and to understand. This book is an excavation, then, and an invitation—to see Brooklyn afresh, to discover that its remotest corners and most familiar places are all layered with memory, alive with meaning and significance. Put another way, it aims to uncover that great cable that links us to the past—what Anton Chekhov described in one of his favorite works, “The Student” (1894), as the “unbroken chain of events flowing one out of another” that leads back from the present. Chekhov’s protagonist is a clerical student named Ivan Velikopolsky who relates the story of Saint Peter’s denial to a pair of elderly widows on a cold winter’s night. Seeing them deeply moved by his telling, Velikopolsky suddenly understands the enduring power of narrative to convey passion and breathe life into the past: “And it seemed to him that he had just seen both ends of that chain; that when he touched one end the other quivered.”2

Brooklyn, long-settled western rump of that glacial pile known as Long Island, has been many things to many peoples over the last five hundred years. It was home to the Leni Lenape Nation of Algonquian peoples for at least a millennium by the time Giovanni da Verrazzano cruised its shores in 1524. To European eyes it was virgin terrain, “a fresh green breast of the new world,” as Nick Carraway marveled in The Great Gatsby—a tabula rasa upon which a whole new script for civilization could be written. It became a rural province of New Netherland until the English named it the West Riding of Yorkshire and, in 1683, Kings County. For the next 150 years this plantation realm fed the rising city across the river, engaging in cultural practices—including chattel slavery—that rendered it closer in spirit to the American South than to New England or the rest of New York. Its quarter closest to Manhattan—the town of Brooklyn proper—became America’s first commuter suburb, a ferry ride and a world away from the rush and bustle of “the city.” Brooklyn evolved into a tranquil realm of churches and homes where affluent New Yorkers—“gentlemen of taste and fortune”—could raise their families safely away from the chaos of urban life. Others came for eternity, tucked beneath the trees and turf in Green-Wood Cemetery, premier resting place for the silk-stocking set from Brooklyn and New York alike.3 The teeming masses also came, decanted from the rookeries of the Lower East Side and Harlem to make Brooklyn home and to labor in the factories of Williamsburg and the Fifth Ward—the busiest industrial quarter in North America for nearly a century. Among them were my own immigrant forebears, who left Little Italy for the relative spaciousness and opportunity across the East River.

By the 1880s, the city of Brooklyn was a strapping, self-assured junior rival of New York, with dreams, schemes, and ambitions all its own. This was the Brooklyn that created America’s greatest rural cemetery; whose shipyards and factories armed the Union during the Civil War; that commissioned Olmsted and Vaux to create their career masterpiece at Prospect Park; that spanned the East River with the longest suspension bridge in the world; that was Gotham’s playground for a generation, where rich and poor alike gathered—at racetracks and turreted seaside hotels, and on the beaches of Coney Island. By the time Roebling’s great bridge opened in May 1883, Brooklyn was all of fifty years old. Founded in 1834, it grew like a weed in manure over the next half century, zipping past Baltimore, Boston, New Orleans, and Cincinnati to become the third largest city in America by the Civil War. It swelled from annexation as well as immigration, absorbing Bushwick and the upstart city of Williamsburg in 1855, New Lots in 1886, and the far-flung country towns of Flatbush, Flatlands, Gravesend, and New Utrecht by 1896. Brooklyn thus reached the apogee of its arc, its moment of maximum power and influence. And then, as we will see, everything changed.

THE ALCHEMY OF IDENTITY

How did Brooklyn become itself? What forces have shaped its singular character and identity? Limning the soul of any city—its genius loci, to quote Christian Norberg-Schulz, the slippery stuff that gives a place timbre, pitch, and intensity—is no easy feat. It is multivalent, runs deep, and is in a constant state of flux. Brooklyn’s place-spirit formed over several centuries and around two principal fulcrums. The first was the land itself. Brooklyn’s distinctive topography—of terminal moraine and outwash plain—is a legacy of the last Ice Age, an era that ended some ten thousand years ago. The miles-deep Laurentide ice sheet was a bulldozer of the gods, gouging out the Finger Lakes, grinding down the Adirondacks, and carving the Hudson Valley only to lose its mojo in the vicinity of present-day Gotham. Here it advanced and retreated twice, as if suddenly unsure of its mission, and left in its wake a great pile of scree known today as Long Island. The backbone of this heap—the conjoined Harbor Hill and Ronkonkoma moraines—is Whitman’s “Brooklyn of ample hills,” a line of elevated ground well charted by place-names: Bay Ridge, Brooklyn Heights, Park Slope, Prospect Park, Crown Heights, Ocean Hill. Below and south of this is the outwash plain, a vast low-slung territory that formed as glacial meltwater and thousands of years of rain flushed much of the high ground toward the sea. The terminal moraine is thus Brooklyn’s continental divide, cleaving the borough into two distinct halves: a hilly Manhattan-oriented northern hemisphere, and a broad, low-slung southern hemisphere closer in spirit to Long Island’s south shore—a landscape “as flat and huge as Kansas,” wrote James Agee, “horizon beyond horizon forever unfolded.”4

As we will see throughout the book, this ancient glacial binary—terminal moraine and outwash plain—has played a vital role in Brooklyn’s growth and development, and remains a key to understanding the borough today. Map the creative class in Brooklyn and you’ll see a ghost of glacial history appear before your eyes. North of the moraine, a stone’s throw from Manhattan, is the city of rapid gentrification, where elders and the poor are dislodged by implacable market forces—where even a tiny apartment now costs a king’s ransom, and nothing, it seems, is not artisanal, batch-made, or cruelty-free. Outwash Brooklyn—basically everything south of a line from Owl’s Head Park in Bay Ridge to Broadway Junction at the Queens border—remains a dominion of immigrant strivers and working-class stiffs, of quiet middle-class bedroom communities and the occasional pocket of both wealth (Midwood and Manhattan Beach) and deep poverty (Brownsville and East New York). It is a world scored still by old lines of race, class, and religion, where you can walk for hours without passing a hipster, a Starbucks, or a bar with retro-Edison lightbulbs; where there are entire communities with ties closer to Tel Aviv, Fuzhou, Kingston, or Kiev than to the rest of the United States.

The second fulcrum vital to Brooklyn’s singularity among cities is its fateful adjacency to Manhattan Island. The relationship between Brooklyn and New York (composed of Manhattan alone until 1874, when it annexed part of the Bronx) has long been a dynamic and complicated one. To the colonial rulers of New Amsterdam and New York—and to the subsequent American city—Brooklyn was the ideal hinterland: close at hand and yet literally and symbolically a separate place, insulated from the center by a natural moat—the treacherous, fast-moving East River. Conditional proximity, for lack of a better term, made Brooklyn a displacement zone of sorts, a site for peoples and practices untenable in the heart of town—suspect religions, racial outcasts, citizen nonconformists, and, later, dirty industrial operations and morally polluting amusements. In this borderland beyond the gates, new freedoms and liberties were abided because they posed little threat to the sanctum sanctorum.5 And so it was across the East River, away from New Amsterdam, that an unorthodox religious group—Deborah Moody’s Anabaptists (and the Quakers who later joined them)—was permitted to establish a settlement in which religious freedom was guaranteed by law. It was across the river, too, that corrupt Dutch West India Company officials were able to make huge illegal landgrabs, and that slavery was far more deeply embedded than in the progressive core. And yet it was also there that freedmen and slaves escaping north on the Underground Railroad—and blacks fleeing the terror of the Draft Riots—found sanctuary, in the African American settlement of Weeksville and among sympathizers on the very farms in Flatlands that once held men in bondage.

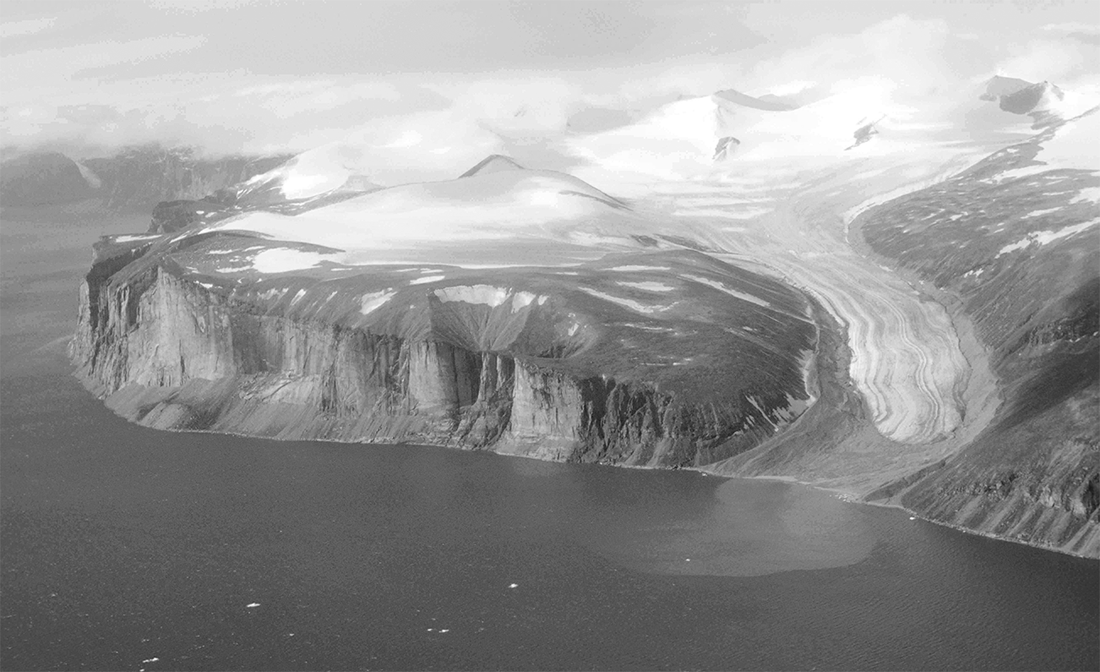

Northeast coast of Baffin Island, looking toward the Barnes Ice Cap, rapidly vanishing last vestige of the Laurentide ice sheet. Photograph by Ansgar Walk, 1997.

As New York grew, so did Brooklyn. It hatched at the river’s edge, eyes fixed on the lodestar city across the way. And just as Manhattan grew north from the Battery, giving the world that enduring binary of uptown and downtown, Brooklyn began in the north and spread south. Put another way, Brooklyn reversed Manhattan’s polarity. Brooklyn north of the terminal moraine hardened into cityscape by about 1915; nearly everything to its south, with the exception of the old rural towns, the amusement district in Coney Island, and a handful of early subdivisions along major axes like Ocean and Fort Hamilton parkways and Flatbush Avenue—Kensington, Ditmas Park, Blythebourne in New Utrecht, Bensonhurst-by-the-Sea, Dean Alvord’s Prospect Park South subdivision in Flatbush (with Albemarle Road modeled on Boston’s Commonwealth Avenue)—remained in rural slumber for another generation. Not until the great building boom of the 1920s did the metropolitan tide wash across the “broad and beautiful plain,” as Henry Stiles called it, of Brooklyn’s southern hemisphere. Incredibly, not until the mid-2000s were the last vacant blocks in Brooklyn’s deepest south—along Avenue N in Georgetown—finally built up.6

From the start, the relationship between Brooklyn and New York was one of reluctant symbiosis. Brooklyn suckled at Gotham’s teat, gaining in size and strength by tapping the great city’s flows of people, goods, and capital. The radiant glow of New York—flagship American metropolis—fueled Brooklyn’s fierce drive and ambition. Like a self-possessed kid who refuses to be bullied by a star older sibling, Brooklyn’s civic leaders were driven to match New York drink for drink. It was a competitive relationship of the best sort, with Brooklyn punching above its weight in round after round for most of the nineteenth century. After New York built Central Park, Brooklyn hired the same designers to create an even finer work of landscape art across the river. Land-starved Manhattan could never have a rural cemetery like Brooklyn’s Green-Wood, de rigueur for any city worth its salt in the middle years of the nineteenth century. So self-confident was this rising city, so suffused with youthful energy, that it had the moxie to cast a steel-cable net across the East River to catch hold of mighty Manahatta itself. For Brooklyn understood that if it owed its existence to the great city across the way, the reverse was also true. Without Brooklyn, New York would never have become a great metropolis. Land-poor and girdled by water, the island city was “in the condition of a walled town,” wrote Frederick Law Olmsted, and would have choked on itself without a vast hinterland across the river.7 And as Gotham grew, Brooklyn became ever more vital to its existence. Brooklyn fed New York, took its trash, decanted its masses, housed its workforce, manufactured its goods, and buried its dead. At Brighton Beach and Coney Island—that “clitoral appendage at the entrance to New York harbor,” as Rem Koolhaas memorably put it—the moral corsets of New York society were loosened.8 There, all manner of conduct unbecoming—drinking, gambling, whoring—was not only tolerated but well served. Coney Island enabled and sustained Manhattan’s hyperdensity by bleeding off the pressures and energy of the metropolitan core, playing id to its massive ego.

WATERSHED 1898

Of course, proximity to Manhattan had its risks. Like an acorn that sprouts too near the great oak from which it fell, it was inevitable that Brooklyn would eventually be eclipsed by the Goliath next door. That moment came on the cold and rainy night of December 31, 1897. As the clock struck twelve, the city of Brooklyn passed into history—extinguished for the greater glory of Greater New York City, what the New-York Tribune called “the greatest experiment in municipal government that the world has ever known.” While rockets burst over jubilant revelers in Manhattan, Brooklyn’s social and cultural elite mourned the demise of their proud independent city—“the moral center of New York,” as the Daily Eagle ruefully put it. Never had so large and influential a metropolis been so subsumed by a neighboring rival. Consolidation overnight made New York the largest city on earth after London, fulfilling Gotham’s “imperial destiny,” as Abram S. Hewitt put it in 1887, “as the greatest city in the world.”9

The mastermind of this forced marriage was Andrew Haswell Green, an extraordinary administrative polymath and political reformer who built many public works, broke the Tweed ring, helped create Central Park, and founded a succession of major institutions—among them the New York Public Library, American Museum of Natural History, and New York Zoological Park (Bronx Zoo). It was in an 1868 memo to the Central Park Commission that Green first sketched out his vision of a future city “under one common municipal government.” Consolidation was never a popular movement in Brooklyn, but it had the backing of merchants, bankers, and the power-ful real estate industry. It was also supported by that dean of Brooklyn civic life, James S. T. Stranahan, a Green-like spirit who—as we will see—played a formative role in creating Prospect Park and the Brooklyn Bridge. Consolidation was Stranahan’s last great campaign (he died just months after its consummation). As the issue came to a head, the Brooklyn Consolidation League and other groups canvassed the city to convince voters that being part of Greater New York would halve Brooklyn taxes, clear its mounting debt, raise property values, and bring about a profusion of public works—including access to Croton water and a much-needed second bridge across the East River. The Consolidation League was checked by the fiercely anticonsolidationist editorial board of the Eagle, and by a well-funded group known as the League of Loyal Citizens. Though it included some of Brooklyn’s most respected church and civic leaders, the league used scare tactics that alienated many potential supporters. Much of this fearmongering involved race, ethnicity, and religion. The league depicted Manhattan as a whoring Mammon that would contaminate the pure and pious City of Churches. Its vision of Brooklyn was a city of native-born citizens “trained from childhood in American traditions,” a white, Protestant mother-land with deep Yankee roots that risked being overrun by the swarthy immigrant hordes of the Lower East Side—“the political sewage of Europe,” as the Reverend Richard S. Storrs of Brooklyn Heights put it. The Consolidation Referendum was approved by nearly 37,000 votes in New York; in Brooklyn it passed by a mere 277.10

“Consolidation Number,” an 1897 special edition of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle celebrating the coming formation of Greater New York City, with the five boroughs rather improbably represented as virginal maidens. Brooklyn Public Library, Brooklyn Collection.

FIELD OF DREAMS

Consolidation profoundly altered the genetic code of Brooklyn, as if its DNA had been exposed to a potent source of radiation. But the effects were delayed, like an illness that lay dormant for years before showing signs or symptoms. For most of a generation, Brooklyn’s old-guard Protestant elite stayed put and continued to campaign for the improvement of their beloved city—even if it was now a mere borough of Greater New York. To Manhattanite expansionists like Andrew Green, meanwhile, Brooklyn was a vast field of dreams—a tabula rasa onto which all sorts of metropolitan fantasies could be projected. The colonizing gaze hardly troubled Brooklyn’s elite; for Greater New York’s expansionist plans—its embrace of Brooklyn as a kind of test bed and laboratory for urban experimentation—elided seamlessly with Brooklyn’s own ambitions for growth, development, and greatness. This created, from about 1900 to the mid-1930s, a synergy that fueled an extraordinary range of projects and proposals promoted by Brooklyn boosters and metropolitan expansionists alike—two more bridges across the East River, subway lines, a great waterfront park that included the world’s biggest sports stadium, a deepwater port larger than anything in Europe, the best airport in North America.

It was also to Brooklyn in this period that, much as its Protestant old guard feared, countless immigrants from across the East River came to find their American Dream. The Manhattan and Williamsburg bridges decanted the overcrowded tenements of the Lower East Side, channeling tens of thousands of working-class Germans, Scandinavians, Jews, Italians, Poles, and Irish into Williamsburg, Bushwick, Greenpoint, Red Hook, Sunset Park, and the industrial district west of the Navy Yard. By the mid-1920s a residential building boom unprecedented in US history had created a vast tapestry of middle-class streetcar suburbs across Brooklyn’s outwash plain, where young families could find “room to swing a cat,” as P. G. Wodehouse and Jerome Kern versed it in “Nesting Time in Flatbush.” The coming of so many Catholic and Jewish southern and eastern Europeans in this era was a last straw of sorts for Brooklyn’s Anglo-Dutch elite. By the late 1920s they were fleeing in droves for the upscale suburbs of Westchester, Long Island, and New Jersey. My mother used to recall how, on walks with her father in the 1930s, she would marvel at the aged Anglo-Dutch widows sweeping the stoops of their glorious brownstones on South Oxford Street; last of their breed, they were relics of a lost world whose families had long ago fled to Scarsdale, Bronxville, or the North Shore.

Linked fates: looking east toward Brooklyn from the Woolworth Building, 1916. Photograph by Irving Underhill. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

IN A VASSAL STATE

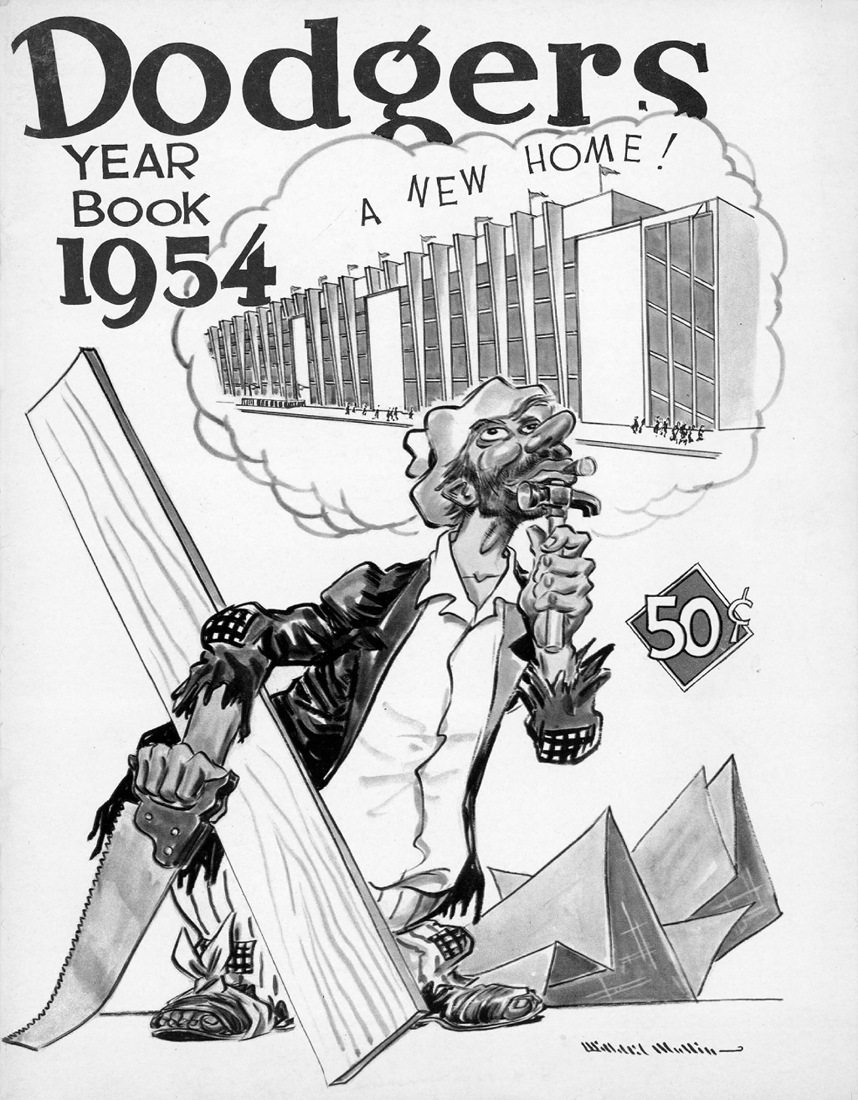

The Great Depression brought about another inflection point in Brooklyn’s evolution. By the mid-1930s, the old order of Anglo-Dutch Brooklyn had largely been supplanted by the borough’s surging white-ethnic population. The newcomers were fiercely ambitious in their own right, but also keenly aware of their provisional status in a society still dominated by its white, Anglo-Saxon charter culture. One did not have to travel far to find evidence of just how hated one was as a Jew or Catholic in America: when Al Smith campaigned for the presidency in 1928, there were Klan rallies and cross burnings all over Long Island. Internalizing outsider status can fuel deep anxiety about one’s place in the world and breed a sense of self-loathing. In Brooklyn, these immigrant insecurities were validated and confirmed by the borough’s own subaltern, “outer” rank vis-à-vis mighty Manhattan. By now, the keen competitive stance Brooklyn once had with its East River rival—its eagerness to beat Manhattan at its own game—had greatly diminished. Consolidation robbed Brooklyn of not only its independence, but much of its moxie and optimism. After World War II, the once-proud city had developed a gnawing inferiority complex. Brooklyn began to see itself as colonized terrain, a vassal state forever in Manhattan’s shadow. It was the eternal underdog—feisty and bombastic and yet consumed by a chronic sense of inadequacy, a Fredo Corleone of cities. The enduring symbol of this subaltern realm was, of course, the Brooklyn Dodgers—a club defeated in six out of seven World Series matchups with the New York Yankees, and that finally triumphed in 1955 only to double-cross their fans by departing for sunny California two years later. The “Dodger betrayal” became a bitter trope for all the crushed hopes and failures of postwar Brooklyn and its white-ethnic social order.

Of course, self-loathing is generally returned with gleeful interest by the world. Brooklyn became the punching bag of cities, the butt of jokes, an object of ridicule that the rest of America could look down its long WASP nose at. Brooklyn’s husky patois—dawg for “dog,” pitchuh for “picture,” and of course cawfee—was mocked from stage and screen. Rapidly vanishing now, it was something to wrap one’s ears about. I remember an aunt telling a story at my grandmother’s Borough Park dinner table when I was a child—something involving an “earl.” Confused—I thought she was referring to English royalty—I tugged my father’s sleeve and whispered, “Dad, who is this earl?” Rarely heard today, earl was how working-class Brooklynites of a certain age pronounced “oil.” Conversely, the word “earl” itself would have been pronounced oil, which recalls the great Rogers and Hart song “Manhattan,” made famous by Ella Fitzgerald, in which a love-struck boy and goil marvel at the city’s romantic allure. But the ridicule could be brutal, and always the most withering came from the high cultural elite—the same class that now stumbles over itself for a Park Slope brownstone, whose trust-funded children have colonized the industrial wastes of Red Hook and Bushwick. Exeter-and-Harvard-educated James Agee, on a failed 1939 assignment for Fortune magazine, ventured bravely across the East River to discover in Brooklyn “a curious quality in the eyes and at the corners of the mouths, relative to what is seen on Manhattan Island: a kind of drugged softness or narcotic relaxation,” much the same look “seen in monasteries and in the lawns of sanitariums.” And though possessing something of a center (“and hands, and eyes, and feet”), Brooklyn was in Agee’s view mostly “an exorbitant pulsing mass of scarcely discriminable cellular jellies and tissues; a place where people merely ‘live.’”11

To Truman Capote, Brooklyn was a benighted realm filled with “sad, sweet, violent children,” homeland of the Philistine mediocrity, the man who “guards averageness with morbid intensity.” He called Brooklyn a “veritable veldt of tawdriness where even the noms des quartiers aggravate: Flatbush and Flushing Avenue, Bushwick, Brownsville, Red Hook.” Any mention of it brought forth “compulsory guffaws,” he mused, for Brooklyn was the nation’s laughingstock. “As a group, Brooklynites form a persecuted minority,” he wrote in 1946; “their dialect, appearance and manners have become . . . synonymous with the crudest, most vulgar aspects of contemporary life.” Capote heaped plenty of highbrow scorn on Brooklyn, but even he recoiled at just how cruel all this mirth making at the borough’s expense could be. The teasing, which “perhaps began good-naturedly enough, has turned the razory road toward malice,” he observed; “an address in Brooklyn is now not altogether respectable.” He also understood the borough’s vast complexity better than most. To Capote, Brooklyn was “terribly funny,” but also “sad brutal provincial lonesome human silent sprawling raucous lost passionate subtle bitter immature perverse tender mysterious.” Capote moved to Brooklyn not long after penning those lines, renting an apartment in the Willow Street home of his friend—set designer and former February House denizen Oliver Smith. “I live in Brooklyn,” Capote wrote in perhaps the greatest backhanded compliment ever paid a city—“By choice.”12

Often the most bitter vitriol came from the borough’s own, to whom success was a measure of distance gained from their native place. My mother could be scornful of family and friends who stayed put in her old neighborhood by the Brooklyn Navy Yard. Indeed, the mark of arrival was to leave. “The idea,” wrote Pete Hamill, “was to get out.”13 Henry Miller reviled the Bushwick and Williamsburg of his youth, describing Myrtle Avenue as “a street not of sorrow, for sorrow would be human and recognizable, but of sheer emptiness: it is emptier than the most extinct volcano . . . than the word God in the mouth of an unbeliever.” Down this grim way “no miracle ever passed, nor any poet, nor any species of human genius, nor did any flower ever grow there, nor did the sun strike it squarely, nor did the rain ever wash it.” See Myrtle Avenue before you die, he implored, “if only to realize how far into the future Dante saw.” Age did nothing to diminish Miller’s odium. In a 1975 documentary, the octogenarian author recalled his birthplace as a “shithole . . . a place where I knew nothing but starvation, humiliation, despair, frustration, every god damn thing—nothing but misery.”14 Such deep loathing for one’s birthplace and cradle created a population that, as we will see, tolerated some of the most egregious acts of urban vandalism in postwar America. Place-hatred does not breed a culture of civic activism or preservation, especially when it’s fused with poverty. This is one of the reasons why city officials were able to raze unopposed most of the blocks south of the Navy Yard for the largest single housing project in American history; and why Robert Moses was able to bulldoze the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway across Red Hook and Williamsburg with nary a whimper from the locals, when a similar project in the Bronx—the Cross Bronx Expressway—raised howls of opposition from the people of East Tremont, who loved their neighborhood and fought bitterly to save it.

It may well be that Brooklyn’s strange alchemy of ambition and self-loathing is precisely why it has churned out more raw talent than any other city in America. The sons and daughters of Brooklyn were hungry, straining at the harness, eager to prove themselves to a cynical, mocking world—or at least to that exalted realm across the East River, the very incarnation of worldly power, wealth, and splendor. And they did just that. There is no quarter of modern life in America that Brooklyn’s gifted offspring have not touched or transformed. And there were plenty of offspring to go around: it is often said that a quarter of all Americans can trace their family ancestry through Brooklyn. Even a partial list of luminaries born or raised in this crossroads of the world is dazzling: Aaliyah, Woody Allen, Darren Aronofsky, Isaac Asimov, zoning pioneer Edward Murray Bassett, Pat Benatar, Mel Brooks, William M. Calder (father of daylight saving time), Al Capone, Shirley Chisholm, Aaron Copland, Milton Friedman, George and Ira Gershwin, Rudy Giuliani, Doris Kearns Goodwin, Arlo Guthrie, Lena Horne, the Horwitz brothers of Three Stooges fame, Jay Z, Jennie Jerome (Winston Churchill’s mother), Michael Jordan, Alfred Kazin, Harvey Keitel, Carole King, C. Everett Koop, Spike Lee, Jonathan Lethem, housing pioneer William Levitt, Vince Lombardi, Norman Mailer, Arthur Miller and Henry Miller, Zero Mostel, Eddie Murphy, The Notorious B.I.G., Rosie Perez, Norman Podhoretz, Nobel physicist Isidor I. Rabi, Lou Reed, Buddy Rich, Joan Rivers, Chris Rock, Carl Sagan, US senators Bernie Sanders and Chuck Schumer, Jerry Seinfeld, Beverly Sills, Nobel economist Robert Solow, Barbara Stanwyck and Barbra Streisand, George C. Tilyou, John Turturro, Mike Tyson, Wendy Wasserstein, Walt Whitman, the Beastie Boys’ Adam Yauch.

Cover of the 1954 Dodger’s Yearbook, envisioning a dream that would never happen—not in Brooklyn, at least. Collection of the author.

High view of downtown Brooklyn, 1962. Photograph by Thomas Airviews. Collection of the author.

Brooklyn reached its peak of population in the immediate wake of World War II—a conflict it played no small part in winning (seventy thousand workers at the Navy Yard churned out seventeen warships between 1940 and 1945, including some of the most powerful ever built). But the winds of fortune changed fast. As we will see, a confluence of internal and external forces—the collapse of industry and loss of factory jobs, the lure of the suburbs, surging street crime, a breakdown of social order—began pulling Brooklyn apart. By the mid-1970s, when I was a child growing up in Marine Park, Brooklyn had been brought to its knees. Wracked by a cacophony of social ills, Brooklyn—indeed, most of New York—was a city under siege. More than half a million residents had fled the borough by then, panicked by its changing demographics, spooked by the boogeyman of race, paralyzed by legitimate fears of violent crime. The serial loss of anchor institutions—the Brooklyn Eagle (1955), the Dodgers (1957), Ebbets Field (1960), Steeplechase Park (1964), the Navy Yard (1966)—convinced them that the borough’s best years were behind it. And so they left, abandoning some of most glorious residential urbanism in North America for car-dependent suburbs, trading townhouses and Tudor-castle apartments for stick-built ranch homes in subdivisions shorn of street life and far from the centers of culture—pawning, in effect, the family jewels for a car and a cardboard box. It would remain for their children and grandchildren to find a path back and rediscover the extraordinary place they had left behind.