CHAPTER 2

LADY DEBORAH’S

CITY BY THE SEA

For we are as a young tree or little sprout . . .

for the first time shooting forth to the world.

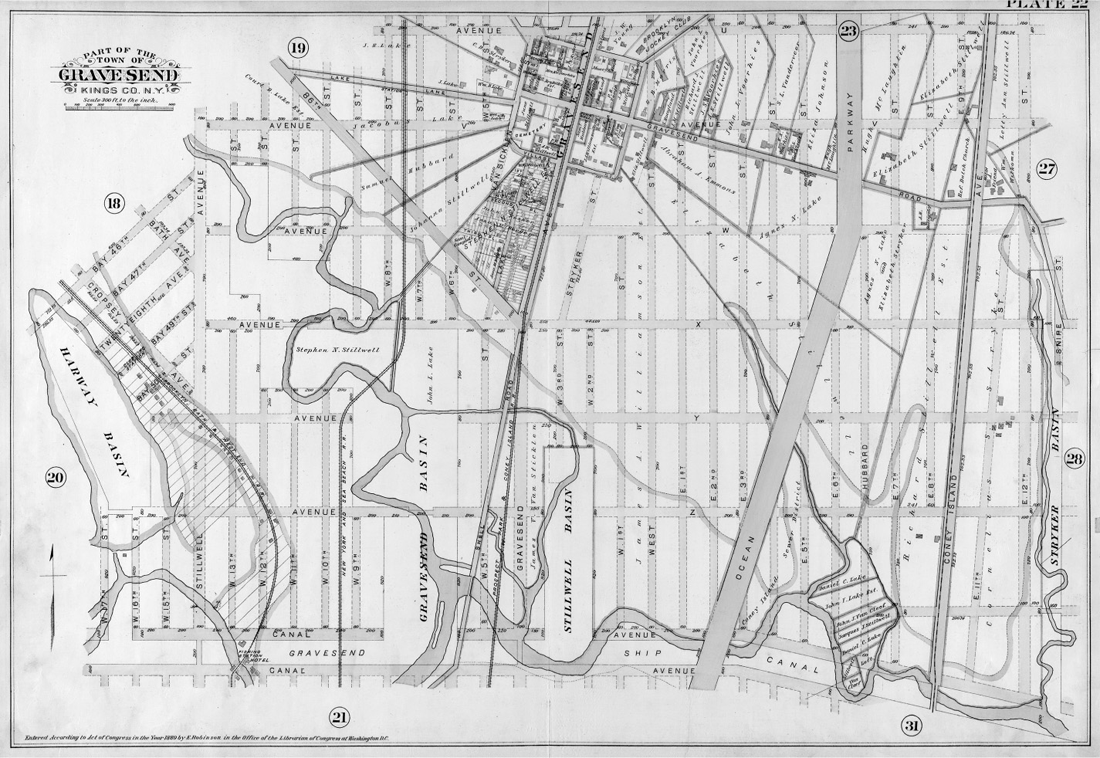

—GEORGE BAXTER ET AL., 1651

Two miles east of Gerritsen Creek is an urban fossil—the remains of one of the oldest planned towns in North America, the first founded by a woman and the first to mandate religious freedom by formal charter. Unlike the Lott house, the sublime order of Gravesend is not evident to an explorer on foot. The streets here appear jumbled and chaotic—some inexplicably short, others set at crazy angles. This is not a particularly charming part of town, not a place where one expects to find a palimpsest from Gotham’s deepest past. The F train lumbers noisily over McDonald Avenue, above the body shops and roofing suppliers. A furniture outlet sits on one corner, near a Chinese steel fabricator, a Korean Bible church and a sketchy-looking nightclub. But rise above the ground-plane chaos here and something extraordinary pulls into focus—a tiny four-square grid, cocked at an odd angle from the city grid, a Cartesian insect trapped in urban amber.

It is a monument to a mysterious soul—an enigmatic Englishwoman named Deborah Moody, whose life and ultimate fate have perplexed antiquarians for generations. She was a child of the nobility, born around 1585 to the Dunch family of Priory Manor, Little Wittenham, in the county of Berkshire. Her mother was Deborah Pilkington, daughter of the bishop of Durham; her father, Walter Dunch, had been a member of Parliament during the reign of Elizabeth I. Oliver Cromwell may have been a relative by marriage on her father’s side. In 1606 Dunch married a nobleman named Henry Moody, later granted peerage as a baronet by King James I. The couple made their home at Moody’s estate, Garsdon Manor in Wiltshire, a short walk from the ancient Avebury stone circle—less famous but arguably more significant than its sister UNESCO World Heritage site at Stonehenge. By 1608 the couple had two children, Henry and Catherine. Sir Henry died in 1629, leaving a large fortune. After being widowed, Deborah Moody moved several times and eventually took up residence in London. This transience ran her afoul of a statute limiting the length of time a person could remain away from his hereditary home. It was no trifling matter; for in April 1635 Moody was summoned by the Court of the Star Chamber, which met in secret and was known for harsh and draconian rulings. The court found “Dame Deborah Mowdie” guilty and gave her forty days to get back home to Wiltshire—“in the good example necessary to the poorer classes.” It has long been assumed that around this time Moody also began espousing dangerously radical ideas about religion, becoming a convert to Anabaptism, a heretical creed in England. As Austin P. Stockwell put it in 1884, Moody evidently “chafed under the unlawful restraints of such a civil and ecclesiastical despotism” and in 1639 left England for the presumed freedom and tolerance of America. If this was indeed her motivation for taking leave of Albion—recent scholarship suggests otherwise—she was soon to be disappointed.1

Deborah Moody’s vernal grid. In this 1924 aerial photograph, traces of Gravesend’s original radiating field boundaries can still be seen. Only one remains today, preserved in the form of Lake Place west of the town center. Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division, The New York Public Library.

Some twenty thousand Puritans emigrated to the Massachusetts Bay Colony between 1629 and 1640, many of whom settled in a chain of coastal towns north of Boston. Deborah Moody was among them. Exactly when she set foot in the New World is unclear, but by early 1640 she had made her way to Saugus, and on May 13 gained approval from the Massachusetts General Court to purchase a spread of several hundred acres known as the Swampscott farm. The transaction left her nearly bankrupt—she was “almost undone,” wrote Thomas Lechford in 1641, “by buying Master Humphries farm.” Moody joined the Puritan congregation in nearby Salem, a place whose own date with history was fast approaching. It was there that Moody became “imbued with the erroneous idea,” as chronicler Alonzo Lewis put it in 1844, “that the baptism of infants was a sinful ordinance.” The whole issue of the validity of infant baptism may strike us as ecclesiastical hairsplitting. Anabaptists argued that nowhere in scripture was such a practice sanctioned, and that for baptism to have any meaning, the individual undergoing the rite must possess some minimal understanding of its implications. In their view, to offer a whimpering infant—wholly ignorant of right and wrong—admission to the Kingdom of Heaven was blasphemous. Why not also baptize the barnyard cat? Most Protestants opposed the Anabaptist position, as did the Roman Catholic Church—hardly surprising given the high rate of infant mortality at the time. Moreover, Anabaptists had a bad reputation. In 1534, a group of them in Münster had attempted to establish a theocracy, advocating the use of force to bring about the New Jerusalem predicted in scripture. Fear that all Anabaptists were hotheaded radicals led to severe persecution of the sect in Europe; tens of thousands were martyred, often by drowning. To Winthrop and the Massachusetts Puritans, Anabaptism was right alongside Quakerism as one of the “damnable heresies” threatening their New World project. Moody, who was said to have “imbibed” her Anabaptism from Roger Williams, founder of the Rhode Island Colony, soon learned just how deep this antipathy ran.2

Neolithic henge and stone circles, Avebury, Wiltshire, close to Deborah Dunch’s childhood home, Avebury Manor (upper left). Photograph by Detmar Owen, 2017.

The Puritan clerisy was in no mood for theological magnanimity in 1640, especially involving a woman. Only several years earlier, Anne Hutchinson had stirred up a hornet’s nest for mocking the pious “learned Scollers” and professing Antinomianism—a belief that faith alone determined one’s salvation, not obedience to some compulsory code of moral law. To Winthrop, Hutchinson posed a grave threat to his “Modell of Christian Charity.” She was arrested in 1637, convicted of heresy, and banished from the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Hutchinson—an inspiration for Hester Prynne in Nathaniel Hawthorne’s Scarlet Letter—made her way to Rhode Island and then New Netherland, where she settled at Pelham Bay in the Bronx. Hutchinson’s life among the Dutch was brief; she was murdered, along with several of her children, by a band of Siwanoy Algonquins in August 1643. Now Winthrop had another Jezebel on his hands. On December 14, 1642, after several reprimands, Moody was arrested and arraigned with two other women at the Quarterly Court in Salem, for “houldinge that the baptizing of Infants is noe ordinance of God.” Winthrop then enacted a decree calling for the immediate expulsion of Anabaptists, accusing them of subverting Puritan rule and even questioning the “lawfulness of making war.” They were, he wrote, “incendiaries of the Commonwealth, and the infectors of persons in matters of religion . . . troublers of churches in all places where they have been.” Now anyone who condemned or opposed baptizing infants risked being banished to the wilderness like the scapegoat of the Israelites. And speaking out on the matter was hardly necessary; Winthrop’s ordinance made clear that even persons who “purposely depart the congregation” during a baptism would be arrested for sedition. Thus facing expulsion from Massachusetts Bay, Moody took off on her own, striking west for New Netherland in early 1643. “My Lady Moody,” mourned the Reverend Thomas Cobbett of Saugus, “is to sitt down on Long Island, from under civil and church watch.” Nor would she go alone: a large group of fellow worshippers from Salem and neighboring congregations joined her—all of whom, Winthrop railed, Moody had “infected with Anabaptism.” And yet Winthrop admitted a begrudging admiration for this thorn among his New World roses—“My Ladye Moodye,” he called her, “a wise and anciently religious woman.”3

New Netherland—booming, profane, and lusty—was a world away from the black-frocked severity of Puritan Massachusetts. Effectively a free-trade zone established by the Dutch West India Company, its first order of business was business. The burgeoning provincial capital of New Amsterdam, at the southern tip of Manhattan, was a medley of ethnicity, race, and creed—“a polyglot community, a confusion of tongues and people drawn from all over the world.”4 It was as tolerant of difference and dissent—within reason—as the Puritan theocrats were not. An eclectic array of freemen, slaves and indentured servants, merchants, seamen, and traders gathered on the cobbled streets of embryonic Gotham, mixed with an even more motley assemblage of “losers and scalawags,” as Russell Shorto has put it, “waiting around for the winds of fate to blow them off the map.” It was here that Deborah Moody and her Anabaptist band came to build a new life. They were not only tolerated but warmly welcomed, for very practical reasons. The director of New Netherland, Willem Kieft, couldn’t care less when a baby was baptized. What he needed were permanent settlers, pious or not, who would make the desert bloom, feeding New Netherland and turning it into a lasting colony. Traders and merchants made for a thriving entrepôt, but without a stable base of agrarians New Netherland would never sustain itself or grow. And here was a whole band of farmers and artisans, a little village in the making! All they needed was some land, which Kieft had more of than he knew what to do with. In June 1643 Moody was issued a patent for a large tract of land near Coney Island, a place far removed from New Amsterdam just in case the English newcomers caused trouble. Kieft named the place Gravesend, not for the English port city, but ’s-Gravenzande, his birthplace on the Maas River delta in Holland.5

The newcomers threw themselves into the long work of settlement. But there was trouble in the land. Willem Kieft was possibly the worst chief executive ever to rule the future New York City, an impulsive tyrant whom Washington Irving satirized as “William the Testy”—a waspish tinhorn prone to “valorous broils, altercations and misadventures.” Only months before Moody’s arrival, Kieft touched off a bloody conflict with local Indians after they resisted his attempts to squeeze them for tribute. When his Council of Twelve Men—the first representative democratic body in the Dutch colonies—balked at endorsing a plan of war, he simply dissolved it and forbade the men to meet. In February 1643 Kieft sent troops to attack a refugee encampment of Weckquaesgeek and Tappan Indians near today’s Jersey City, killing eighty people. “Young children, some of them snatched from their mothers, were cut in pieces before the eyes of their parents,” wrote David de Vries, Kieft’s former council chief; “other babes were bound on planks and then cut through, stabbed and miserably massacred so that it would break a heart of stone.” De Vries was sickened by the slaughter, which he described as “a disgrace to our nation.” Kieft, on the other hand, thanked the men for this “deed of Roman valor.” In retaliation, Algonquin warriors carried out a series of equally brutal raids throughout the region in subsequent months, including the one that killed Anne Hutchinson at Pelham Bay. By the time “Kieft’s War” was over in the fall of 1645, hundreds of colonists and some sixteen hundred Indians had been killed. Trade was at a standstill and farms lay idle, immigration had all but ceased, and many settlers left the colony altogether; those remaining were on the verge of mutiny. All told, it was a very bad time to be coming on board.6

Indeed, Moody’s fragile encampment was attacked repeatedly in its first year at Gravesend, forcing her band to seek refuge at nearby Nieuw Amersfoort. Eventually the settlers erected stout enough dwellings and a defensive stockade that enabled them to repel marauders. Yet survival seemed precarious, so much so that Moody contemplated returning to Massachusetts. In the aftermath of Hutchinson’s murder in the fall of 1643, she wrote John Winthrop to ask his advice. It is not known whether he responded, but upon learning of her query, John Endicott—deputy governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony—penned a missive to Winthrop himself in which he advised against allowing Moody back, unless she signal repentance and “leave her opinions behinde her”—for “shee is a dangerous woeman,” he warned, and “it is verie doubtefull whither she will be reclaymed.” Endicott then added—one imagines with a sudden shudder of dread—“The Lord rebuke Satan the adversarie of our Soules” (author’s italics). Hostilities between the Dutch and the Indians eventually cooled, and on December, 19, 1645, Governor Kieft issued the Gravesenders a new and more robust patent to the land that had been their tenuous home for more than two years now. In it, Kieft granted “ye Honoured lady Deborah Moody” and her associates “a certaine quantitie or p’cel of Land, together with all ye havens, harbours, rivers, creeks, woodland, marshes. . . . uppon & about ye Westernmost parte of Longe Island.” The settlers were to “injoye & pocesse” this land with full authority “to build a towne or townes with such necesarie fortifications as to them seem expedient.” But the most remarkable passage came next, for in it Kieft stipulated that the Gravesenders were to both govern themselves—to “erect a bodye pollitique” and make “such civill ordinances as the Major part of ye Inhabitants . . . shall thinke fitting for theyr quiett & peaceable subsisting”—and enjoy “free libertie of conscience . . . without molestation or disturbance from any Madgistrate or Madgistrates or any other Ecclesiasticall Minister that may p’tend jurisdiction over them.” Deborah Moody’s Gravesend settlement thus became only the second in America founded on principles of religious freedom, established nine years after Roger Williams founded Providence Plantation as a haven from religious persecution. But Gravesend was the very first to legislate religious freedom in its founding charter. In this, Moody’s town was five years ahead of the Toleration Act that mandated religious tolerance in Lord Baltimore’s Maryland colony, and twelve years ahead of the seminal Flushing Remonstrance.7

What kind of place was Gravesend circa 1645? It was wild, to be sure, much of it heavily wooded and home to wolves, bear, and possibly the long-extinct Eastern elk. It was flushed by seaborne winds, scored with tidal creeks, on the edge of a bay teeming with fish and crabs. But it was not a howling wilderness. In a letter to John Winthrop’s son, George Baxter described the land Kieft allotted his group as “a place not yet settled on Long Island, and so commodious that I have not seene or knowne a better.” In fact it had long been inhabited by Native Americans, and though the exact spot chosen for the new town had never been settled, it was a junction of two old Indian paths—one, today’s McDonald Avenue, ran south to the sea from the Mechawanienk trail (Kings Highway); the other, Gravesend Neck Road, led east to the Strome Kill and Shanscomacoke. There were also at least two other Europeans in the immediate area; for Kieft had granted, in 1639, a two-hundred-acre plantation in the vicinity to a Moor named Anthony Jansen van Salee. Van Salee, known as “the Turk,” was a character every bit as memorable as Deborah Moody, whom he came to know well. His father had been a notorious privateer on the Barbary Coast, a convert to Islam, and ruler of a short-lived city-state called Salé in what is now Morocco. Van Salee was born in Cartagena, Spain, in 1607 and spent time in North Africa and Amsterdam before coming to New Netherland around 1630. He and his salty German-born wife, Grietje Reiniers, were renegades of a different sort, and exiles too: the pair was ordered to leave New Amsterdam after repeated legal disputes, financial trouble, and quarrels with clergy over their libertine ways. The original litigious New Yorker, van Salee was in court more than he was home, hauled in for—among other things—aiming a loaded pistol at slave overseers of the Dutch West India Company and passing off a dead goat as payment for a debt. The angry Moor was derided as a drunk and denounced as a rogue and “horned beast.” At Gravesend, the unrepentant couple evidently got along well enough with Deborah Moody, though the boorish van Salee fought constantly with her Oxford-educated poet son. In the first of several legal actions, Henry Moody dragged van Salee into court after the latter stormed his house, calling him names and abusing his servant with “evil language.” Aside from their shared traits of grit and gumption, it’s unlikely that the pious Lady Moody and Grietje Reiniers would have had much to bond over. Reiniers had been an Amsterdam barmaid before turning to prostitution, a line of work she evidently kept up after marrying van Salee. She regularly provoked moral outrage in New Amsterdam with her licentious behavior, no easy thing in the raffish colony. When some sailors called her a “two pound’s butter whore,” she hiked up her skirt, slapped her rump and shouted “Blaes my daer achterin”—“Kiss my ass,” roughly translated.8

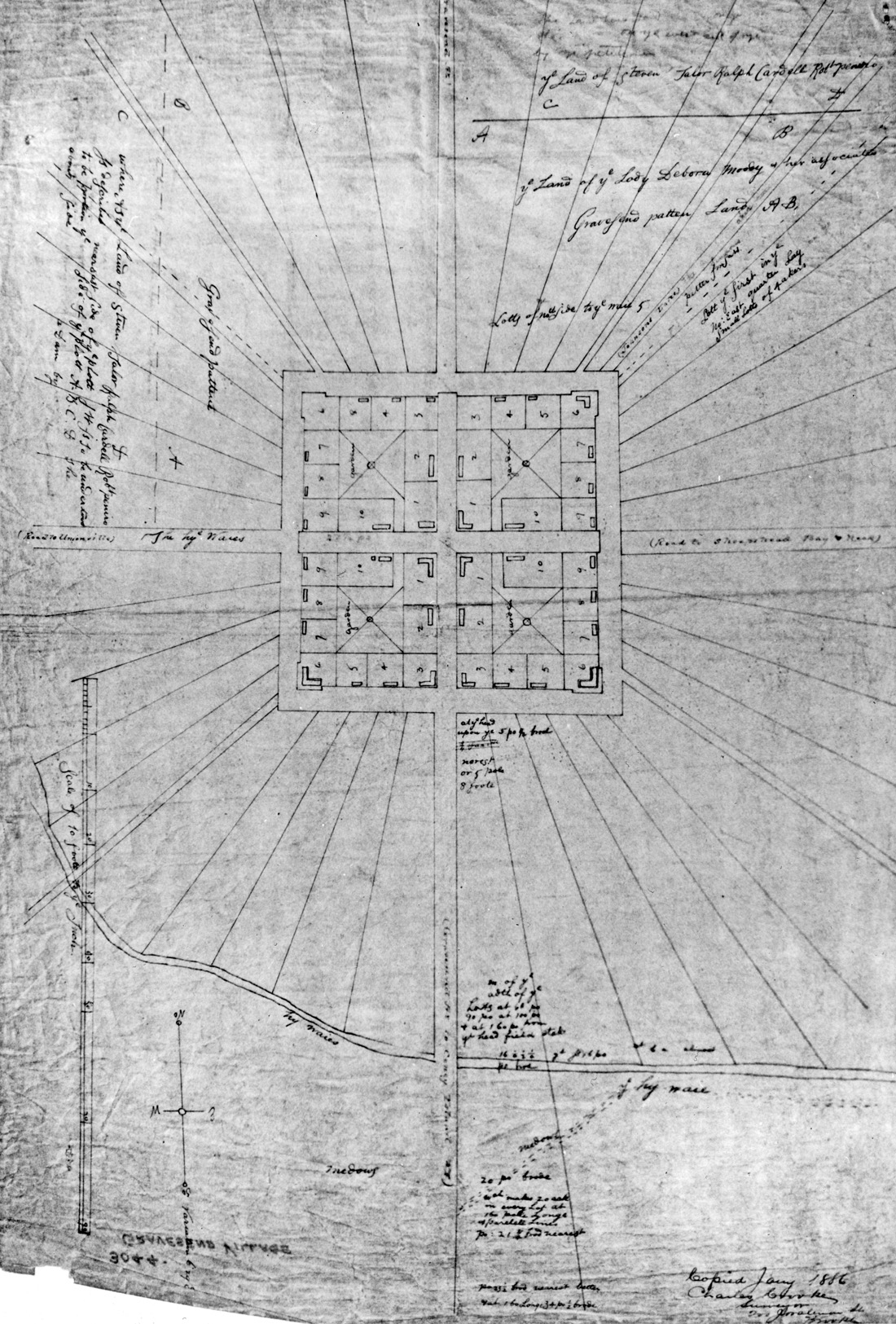

Deborah Moody was America’s first woman town planner; for in this primeval place she etched an exquisite diagram for spatial order: four squares of four acres each, aligned to the cardinal points of the compass and scored by streets running north-south and east-west—the ancient Roman cardo and decumanus on New World soil. It was only the second town in Anglo-Dutch America planned as a precisely surveyed grid, “laid out,” as nineteenth-century chronicler Nathaniel S. Prime opined, “with a great deal of taste.” From its center an array of lot lines were plotted, like spokes of a wheel, to create “triangled” home lots for each of the settler families. Communal pasture land and woodlots lay beyond. As a diagram, the Gravesend plan is one of the most striking in American history—an essential mark of human will on the land, reaching outward across space as if to tap the very life force itself.9 But this was no dreamy Utopia. Given the political situation of New Netherland at the time, the first order of business here was sanctuary and safety. The tight four-square layout made Gravesend easy to defend, aided by a stockade of sharpened timber stakes—a “fence of pallisadowes of six footes.” Close scrutiny of the plan reveals—at each of the four corners—guard posts in the form of tiny vestigial bastions. The radial bloom of planting fields, too, so evocative of a flower in the sun, was itself the result of expedience and pragmatism. Not only could such an array be quickly surveyed from a single station point, but the triangular fields enabled settlers to work their own holdings as close in or as far from the secure town center as the threat of attack necessitated—in time of conflict huddling close to the nest; in time of peace moving outward into a progressively expanding realm. Gravesend may have been founded by a devout noblewoman seeking religious freedom, but it began in a time of war, even surveyed by a military officer—James Hubbard, one of Moody’s original patentees and the town’s first constable or “schout.” Like most English surveyors at the time, Hubbard was trained in the martial arts; and rectilinear town plans—easy to lay out and easy to defend—had been a mainstay of military science since the gridded castra of ancient Rome.10

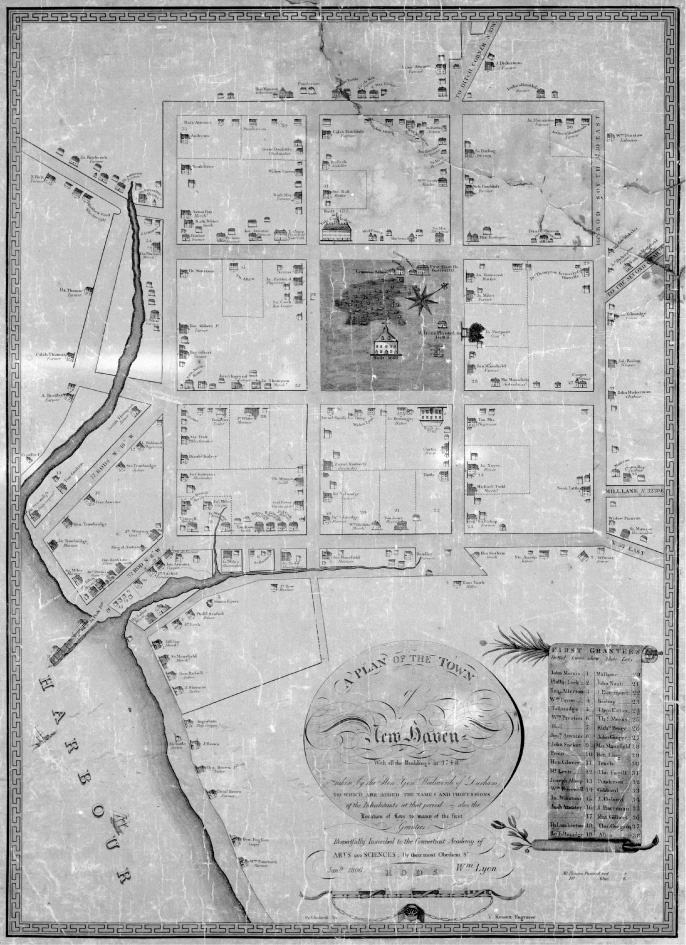

But the Gravesend plan may have drawn upon a yet more lofty source of inspiration. Deciphering its hidden code requires tracing Moody’s journey from Massachusetts to New Netherland. We do not know her exact itinerary, but can be fairly certain the voyage was made by ship and took the group around Cape Cod, past Nantucket and Martha’s Vineyard into the protected waters of Long Island Sound, where they dropped anchor at New Haven. That this place would be of special interest to Moody is clear, for it had been founded only five years earlier by another Massachusetts émigré, John Davenport. As a settlement of religious exiles in a wild landscape, New Haven appears to have been the template for Moody’s own encampment in the wilderness. Like Moody, the “Moses of New Haven,” as Cotton Mather called Davenport, had clashed with the Puritan clerisy over infant baptism, taking an even stricter line than Moody—that the sacrament should be administered only to the infant children of full church members. Davenport yearned to establish a more orthodox Puritan colony than Massachusetts Bay, and eventually struck out with a large following to found a holy city on the Connecticut shore. His orthodoxy extended to the landscape itself; for in Davenport’s hands the Bible became a kind of planning manual used to guide the very design of his holy city. In the summer of 1638, Davenport and surveyor John Brockett began laying out at New Haven one of the most extraordinary town plans in colonial America—a great nine-square grid based on descriptions of the New Jerusalem in the Old Testament. John Winthrop might have been a pious man, but the layout of his “City upon a Hill” at Boston was anything but inspired; Davenport’s “Bible Commonwealth,” on the other hand, carried the word of God out of the meetinghouse and into the streets—literally.11

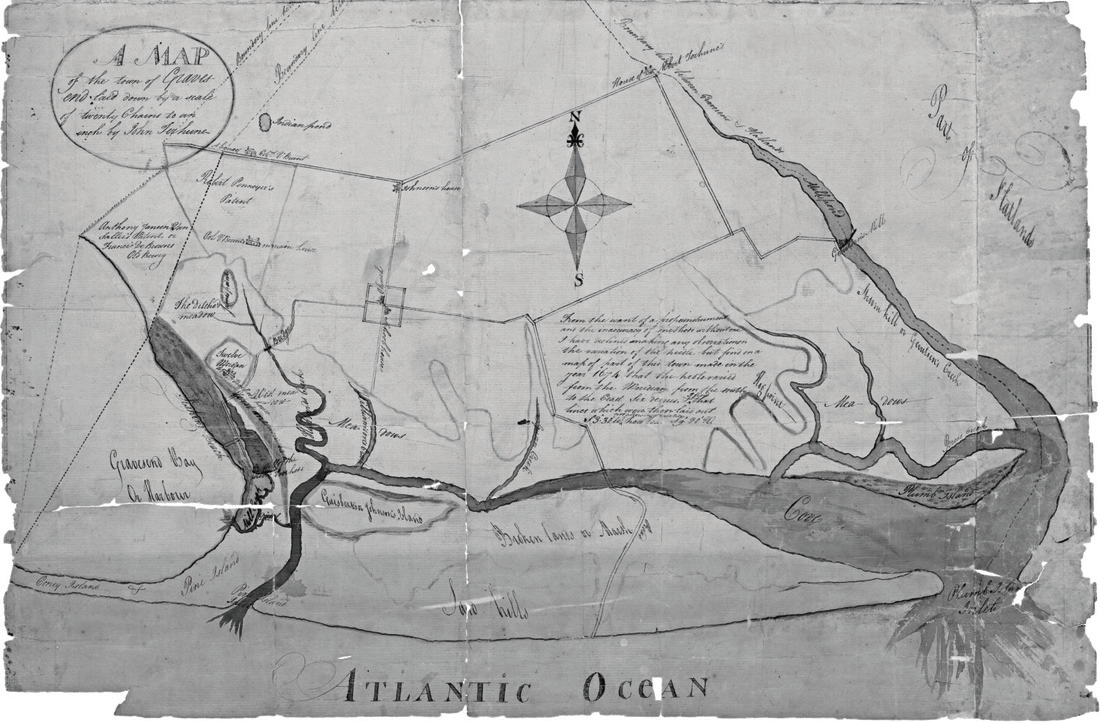

John Terhune map of Gravesend, c. 1674. The town center is just left of center; Gerritsen Creek and tide mill to right of compass rose. New York State Archives—Survey maps of lands in New York State, 1711–1913 (Series A0273–78, Map #429).

Ideal cities—all square with a temple sanctuary in the center—are described in several places in the Bible, but the most detailed are in the book of Ezekiel; there, Davenport observed, “Christ hath given his People a perfect pattern.”12 Chapter 40, for example, provides an exhaustive description of the Holy Temple of the Israelites, stipulating a temple 500 cubits on a side (approximately 750 feet) and giving precise measurements for even alcoves, courtyards, and door jambs. By the early seventeenth century, many of these passages had become the subject of biblical “commentaries,” often illustrated with reconstructions of the plans described within. One of the earliest, by French theologian Sébastien Castellión in 1551, illustrated the Temple of Jerusalem described in Ezekiel 40 as a nine-square grid; another, by Jesuit scholar Juan Bautista Villalpandus, published in 1604 and widely reproduced, included drawings of a nine-square encampment of the Israelites with a temple in the center. It is virtually certain that Davenport—a learned theologian who had studied at Oxford—would have known of these illuminated commentaries. Though he took some liberties in transcribing Ezekiel to Yankee soil—each of Davenport’s nine New Haven squares, for example, is roughly 500 cubits on a side, as if each itself worthy of temple status—New Haven could well have been laid out by the Hebrew prophet himself. Barely five years old, the town would have been very much a work in progress in the summer of 1643 when Moody came ashore, its essential design clear to see.

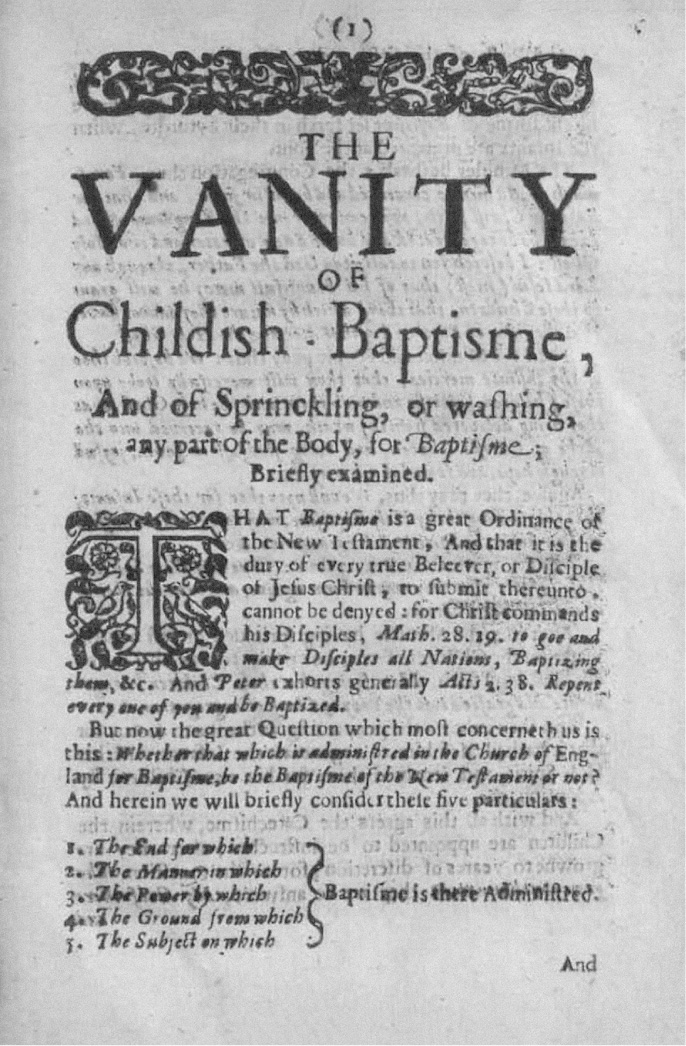

She was not there very long. Despite their shared status as Massachusetts émigrés, Moody and Davenport hardly saw eye to eye on matters religious. An orthodox Puritan, Davenport had played a key role in prosecuting Anne Hutchison only several years before in Boston, and may well have considered Moody a radical heretic too. Indeed, the good woman appears to have stirred up a hornet’s nest in the short time she was at New Haven. The controversy involved her friend Anne Lloyd Eaton, the wellborn widow of Thomas Yale (grandmother of Elihu, future namesake of Yale College), whose second husband was Davenport’s close friend and Oxford classmate Theophilus Eaton, first governor of Connecticut. How Eaton and Moody first met is unknown, but they evidently knew each other from London, and it is probable that Moody stopped at New Haven specifically to see her. There they discussed the issue of baptism, and Eaton asked Moody to lend her a recently published book—Andrew Ritor’s 1642 Treatise of the Vanity of Childish-Baptisme. Eaton read the book in secret, concealing it from her husband and minister Davenport, but shared it with several other women in the community. At worship one Sunday not long after, Eaton suddenly arose from her front-row pew and walked out of the meetinghouse. In the weeks that followed she began absenting herself from baptisms and services generally. When several congregants demanded an explanation for such reprehensible behavior by the governor’s wife, Eaton told them that she had come to doubt the validity of baptizing infants. This prompted Davenport to borrow the borrowed book in order to prepare a series of sermons disproving Ritor, demonstrating that baptism had indeed “come in the place of circumcision, and is to be administered unto infants.” Unmoved by months of lectures and admonition and refusing to repent, Eaton was censured and excommunicated. The episode rocked New Haven and wrecked Eaton’s marriage (poor Theophilus was evidently “denyed conjugall fellowship” for not defending his wife). Moody was long gone by the time all this unfolded, but it is likely that Davenport or Theophilus Eaton had indeed learned she was proselytizing in New Haven and hastened her on her way. For as antiquarian Nathaniel Prime put it in 1845, Moody came into “new difficulties” in Connecticut, “having made some converts to her new opinions.”13

Gravesend town plan, c. 1645, copied from the original by Charles Crooke in 1886. Brooklyn Historical Society.

A Plan of the Town of New Haven With all the Buildings in 1748, James Wadsworth. Engraving by T. Kensett, 1806. Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division.

Andrew Ritor’s Treatise of the Vanity of Childish Baptisme, 1642. British Library.

But Lady Moody appears to have carried off to New Netherland a token of this Yankee New Jerusalem. On a bold venture of settlement herself, she would have been keenly aware of the town-making groundwork so evident at New Haven at the time, the still-fresh lot lines and newly surveyed streets. A measure of Gravesend itself provides the most compelling evidence of a Connecticut connection; for Moody’s four-square Gravesend grid is precisely the size of each of New Haven’s nine constituent squares; if superimposed, Gravesend would snap perfectly into the center of Davenport’s holy matrix, originally the marketplace or public square and long known as the Green. If you walk beneath the “el” on McDonald Avenue from Village Road South to David’s Bread at the corner of Village Road North (“World Famous Rye Bread”) you’ll have gone just over five hundred Babylonian cubits—almost precisely the length of Ezekiel’s Temple. It was as if Moody had carried off a cutting of New Haven to plant on Long Island (ironically, Gravesend and several other coastal English towns were all briefly annexed to Connecticut in 1662, shortly before the English took over faltering, credit-starved New Netherland). The distinctive pattern of planting fields at Gravesend—arrayed about a quadrangular nucleus—may have also been inspired by New Haven. There, a number of roads radiated outward from the nine-square grid, the most direct means of moving between village and hinterland. There is no evidence suggesting the planting fields were themselves arrayed spoke-like about the center; that the town was bounded east and west by creeks would alone have made such a pattern unworkable. Instead, planting lots were laid out between the radiating roads, creating the distinctive “cobweb” form of streets that surrounds New Haven today, to the annoyance of many drivers.14

If New Haven did indeed provide Moody and Hubbard a germ of inspiration for the Gravesend plan, the latter improved on a number of its elements. New Haven’s radiating avenues and streets—Broadway, Prospect, Whitney, State, and Grand to the north and east; Chapel, Legion, Davenport, and Washington to the west and south—converge only roughly upon the town center, whereas the field boundaries at Gravesend, many of which later became roads, did so with mathematical precision. Superior execution is also evident in the town center. The house lots within each of New Haven’s squares were laid out in a seemingly haphazard pattern, while those at Gravesend were fastidiously placed about the perimeter, each with its own garden plot. More telling still is how open space was provided in each plan. At New Haven the central square was set aside as the Green, while at Gravesend shared open space was provided at the center of each quarter. These were initially used for the safekeeping of livestock, but over time they took on a variety of communal uses—one for the town hall, others for the school and a meetinghouse, and the fourth for the burial ground, which still exists today. Finally, it appears that Davenport’s sixteen-acre units proved to be impractically large; for as early as 1802, most of the nine New Haven squares had been further subdivided, into four-acre squares just like those at Gravesend.15

As a town founded by a woman seeking freedom of worship, with a codified guarantee of “free libertie of conscience,” Gravesend not surprisingly would become a haven for other religious dissenters fleeing persecution. In the 1650s it had begun to attract a number of Quakers, who found that the Gravesenders’ own experience with religious intolerance “fitted them to take kindly,” wrote chronicler A. P. Stockwell, “to the peculiar principles of that society.” Certainly there were strong commonalities between Quakerism and Anabaptism. Both claimed an individual relationship to God, rather than one mediated or brokered by an organized church. They were a community of “fellow believers or brothers” in faith. This is codified in the town plan. As Nathaniel Prime noted in his History of Long Island, the original plan for Gravesend contained “no designated site for a house of worship,” nor is any mention made of such a structure in early town records. A 1657 report on the status of New Netherland’s churches claimed that, rather than holding traditional services, the Gravesenders would read to one another, often in each other’s homes. The Religious Society of Friends had been founded in England around 1647 by George Fox, the eldest son of a Leicestershire weaver who sought a more essential relationship with Christ, unmediated by ordained clergy or exacting interpretations of scripture. A powerful speaker, Fox was imprisoned numerous times for blasphemy and at one point was nearly condemned to death (it was in mockery of Fox’s exhortation that one should “tremble at the world of the Lord” that the term Quaker came about).16

In June 1657 a party of English Friends, led by a magnetic young preacher named Robert Hodgson, crossed the Atlantic and visited Gravesend en route to Rhode Island. It was there—reputedly at Lady Moody’s own house—that the first Quaker meeting in America took place. Hodgson also visited Hempstead on Long Island, where he discovered that the magnanimity of Gravesend was the exception rather than the rule. There, while meditating in an orchard, Hodgson was arrested by a Dutch magistrate and sent to prison in New Amsterdam. Willem Kieft might have been a troublemaker, but religious freedom flourished under his administration. His replacement, Peter Stuyvesant, was mean and illiberal on matters of faith, a partisan of the Dutch Reformed Church who barred Lutherans from worshipping, called Jews a “deceitful race,” and reserved special hate for “the abominable sect of the Quakers.” He decided to make an example of the twenty-three-year-old Hodgson, sentencing him to pay a hefty fine or “work two years at a wheelbarrow with a negro.” When he refused to pay, he was chained to a wheelbarrow and sent off to repair a section of the city wall with a slave, who was later forced to whip Hodgson when he refused to work. Stuyvesant then had the young man hung by his hands and beaten within an inch of his life. He was eventually released, but not before Stuyvesant passed an ordinance, in July 1657, that made it illegal for anyone in the colony to host a Quaker in his home.17

Not even Gravesend was safe now. Indeed, the first man hauled to New Amsterdam for violating the ordinance was Gravesend town clerk John Tilton, who “dared to provide a Quaker woman with lodging.”18 It was Stuyvesant’s growing intolerance of religious diversity that led the citizens of Flushing to draft their Remonstrance that October, precursor to the provision of religious freedom in the US Bill of Rights. Not long after, in the winter of 1660, the doomed Mary Dyer preached at Gravesend on a last hopeful mission before returning—against all warnings—to Boston, where she had been condemned to death some months earlier but given a last-minute reprieve at the gallows. This time the ruthless John Endicott had Dyer hanged on Boston Common—killed, incredibly, by a sect of religious fanatics that had crossed the Atlantic to escape persecution. By this time, Gravesend had developed a reputation as an American “Mecca of Quakerism”; poet Gertrude Ryder Bennett called it “one of the most important Quaker colonies in the New World.” Even the revered Quaker prophet George Fox spent time there. Fox sailed to America in 1671 (ironically, his ship was chased one night by a man-of-war from Salé, the Barbary outpost once ruled by Anthony Jansen van Salee’s father). After stopping briefly in Barbados and Jamaica, he sailed north to Maryland in early 1672, and traveled thence on horseback up the coast to Middletown, New Jersey. From there Fox and his party were taken by boat across the Lower Bay, landing at Coney Island and making it to Gravesend by nightfall. Fox “tarried that night” in town before moving on—accompanied by a number of Gravesend Quakers—to Flushing and Oyster Bay, where a four-day “Half Year’s Meeting” was held. Fox again passed through Gravesend in July 1672, attending there “three precious meetings.”19

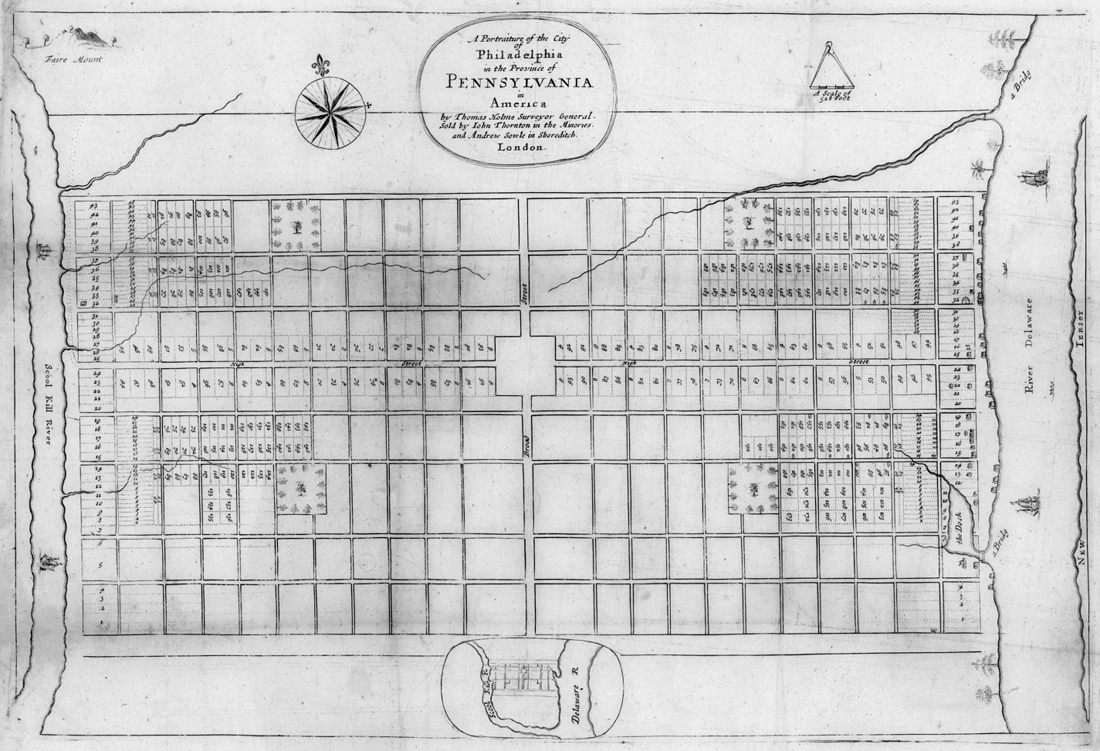

Of course, the American city best known for its Quaker heritage is Philadelphia, founded by William Penn in 1682. It was the third and largest settlement in the Anglo-Dutch colonies laid out in precision form—as a great four-quarter gridiron stretched between the Delaware and Schuylkill rivers. Could it be that Lady Moody’s little grid, each quarter endowed with a square of its own, was the germ of this landmark plan? Even a casual glance at the Penn scheme reveals a layout that fuses elements of both New Haven and Gravesend, with a dominant central space (later filled by City Hall) surrounded by smaller squares in each of the four quadrants. Was Philadelphia the grand culmination of a westward transit of a spatial design idea, from New Haven to Gravesend to the City of Brotherly Love? We know that many Gravesend Quakers migrated west as Dutch intolerance grew, and even after the English took over the colony in 1664. Some settled in Monmouth County, New Jersey; others in Burlington and neighboring towns in West Jersey, the vast province—about half the present Garden State—acquired by a group of Quaker investors, including Penn, in 1677. We also know that Fox, who had been to Gravesend twice, was a friend of Penn’s and visited William and his wife Gulielma at their Rickmansworth home upon returning from the American colonies in 1673. Penn therefore would surely have known of Lady Moody’s sanctuary from religious persecution. Perhaps Penn thus also learned from Fox of Gravesend’s unique plan and its New Haven roots—and that he and his surveyor general, Thomas Holme, had Lady Moody’s vernal scheme in mind when they drafted plans for Philadelphia.20

Unfortunately for Brooklyn partisans, evidence suggests otherwise. It turns out that Penn and Holme were not on the same page, so to speak, when it came to laying out the Quaker city. It was Holme, not Penn, who authored the signature grid, for the latter had in mind a very different, more pastoral arrangement for Philadelphia. Penn was hardly an urbanist—and for good reason: he had lived through two horrific back-to-back events in London that would have driven even Jane Jacobs to the suburbs—the Great Plague of 1665 and the Great Fire of 1666. In both cases, extreme urban density, crowding, and congestion hastened the spread of death and destruction. The very last things William Penn wanted in his New World colony were Old World urban hazards. As he famously put it in a letter, he meant Philadelphia to be not a city but a “greene country towne which will never be burnt, and always be wholesome.” It would occupy a series of parallel hundred-acre “strip lots,” each 825 feet wide and a mile deep, extending down to the Delaware River. Rather than a tight, nucleated settlement between the rivers, Penn’s Philadelphia would have been little more than “an extension of the countryside,” a rustic realm laid out along a sixteen-mile stretch of riverfront. Houses for the colonists would have been placed squarely in the center of each immense lot, not arrayed about urban squares. Indeed, in such a nonurban scheme “residential squares would have been a superfluity,” writes historian Sylvia D. Fries. Penn had dreamed up a subdivision of McMansions, not a city. And the centerpiece of his river-strip scheme? Not a great central space, teeming with markets and life, but a house—Penn’s very own “scituation,” his grand manor, set on a three-hundred-acre estate.21

Thomas Holme, A Portraiture of the City of Philadelphia, 1683. Collection of Historic Urban Plans, Ithaca, New York.

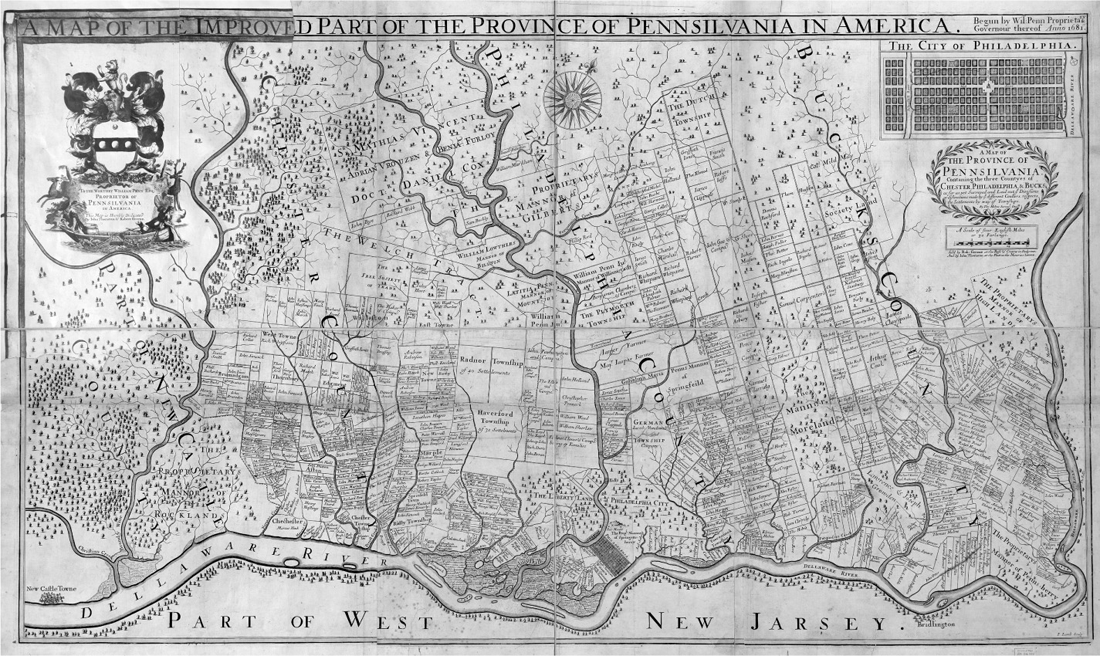

It was the reality of the vast Pennsylvania site—its topography and the fact that much of it was already in private hands—that eventually put the kibosh on Penn’s plan, leading Holme toward a more compact, urban scheme for the highest, driest available land. As for sources, it appears Holme’s looked not to Gravesend or New Haven, but to the Old World—London’s residential squares or possibly Richard Newcourt’s post-1666-fire proposal for rebuilding London, a gridiron with a nearly identical array of internal squares. He may even have had in mind Sir Thomas Phillips’s 1611 plan for the crown settlement of Londonderry, the first planned town in Ireland, where Holme spent some years. But Lady Moody may have had some westward influence yet. As part of his grand plan, Penn envisioned an array of agricultural villages in the hinterlands around Philadelphia—nucleated settlements where “virtuous industry and righteous tranquility” might take root. He described two different methods of land division for these rural towns, the second of which—a central square surrounded by a radial bloom of planting fields—bears a striking resemblance to Gravesend. There, a taut union of field and hearth would assure, Penn wrote, “that the Conveniency of Neighbourhood is made agreeable with that of the land.” Though his regional vision for Philadelphia was only partially realized, two townships northeast of the city proper—Newtown and Wrightstown—were laid out in such starburst form. On the 1720 “Mapp of ye Improved Part of Pensilvania in America,” they appear like embroidered stars winking in a patchwork quilt. Though few traces of colonial Wrightstown survive, several routes around Newtown today—Swamp, Durham, Eagle, Washington Crossing, and Twining roads—clearly originated with the old pattern of radial field boundaries.22

Thomas Holme, A Map of the Improved Part of the Province of Pennsilvania in America, 1695. Note the hub-and-spoke layout of Wrightstown and Newtown, center-right side of map. Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division.

And what of Gravesend and the “American Dido” who founded it? After Willem Kieft’s War ended in late 1645, peace settled over the land and Gravesend prospered for decades. The town appeared to have a bright future ahead of it. The land, after all, was blessed with fertile soil and plentiful timber and game; the seas adjoining abounded with fish, its bays and creeks thick with waterfowl, crabs, and shellfish. It was a commodious place indeed, as George Baxter had so enthusiastically related to Winthrop the Younger in 1644—so hospitable that Gravesend’s founders and Dutch officials alike were confident that the embryonic settlement would soon be a boomtown. In a report to the Dutch West India Company in 1651, Gravesend officials Baxter, James Hubbard, Nicholas Stillwell, and several other signatories envisioned a grand urban future. “We are as a young tree or little sprout now, for the first time shooting forth to the world,” they wrote, but “which if watered and nursed . . . may hereafter grow up a blooming Republic.” Geography, too, seemed in Gravesend’s favor, at first flush at least. The town was on a bay, close to the head of the Narrows and a short haul to both the docks of New Amsterdam and the open sea. But in fact Gravesend Bay was fatally flawed—too shallow to accommodate large seagoing vessels. As merchant ships grew in size and draft, they could no longer drop anchor at Gravesend, dimming its prospects of future port-city fame. “And so,” wrote Peter Ross in his 1902 History of Long Island, “the idea of building a ‘city by the sea,’ which in extent, wealth, and business enterprise, should at least rival New Amsterdam, was reluctantly abandoned.”23

Nonetheless, Gravesend was eventually designated one of three official ports of entry on Long Island by the English—perhaps because it was there that Richard Nicolls anchored his men-of-war on August 18, 1664, to land the forces that would demand Peter Stuyvesant surrender the Dutch colony. By then, Gravesend’s loyalties had been divided for years, its fortunes rising and falling with the affairs of state between England and Holland, the world’s two major, oft-clashing colonial powers at the time. In 1654, with the start of the first Anglo-Dutch War, Stuyvesant’s council decided to stop calling on the Gravesenders to defend or even help repair the fort at New Amsterdam, “so as not to ‘drag the Trojan horse’ within the city’s walls.”24 Later that year some fifty Englishmen attended a clandestine meeting in Gravesend, fueling rumors that there was mischief afoot against the Dutch. The prime suspect was George Baxter, one of Moody’s original Yankee band and Stuyvesant’s English secretary. That year Baxter presented a “Humble Remonstrance” to the director general, complaining of the many officers and magistrates he had appointed “without the consent or nomination of the people.”25 Baxter along with James Hubbard had been elected officers of Gravesend town, in open defiance of Stuyvesant’s order that all such appointments be reviewed by him. Baxter was summarily dismissed and later arrested for hoisting the English flag above Gravesend, pledging loyalty to Lord Protector Cromwell, and “reading seditious papers to the people.” For this he languished in a brig for months until Henry Moody pleaded for his release, after which he returned to England and began lobbying for an all-out invasion of the Dutch colony. As Martha Lamb put it in an 1877 history, Long Island—and especially Gravesend—was “one continual source of anxiety to the men in power at New Amsterdam.”26

Plate 22 of Robinson’s Atlas of Kings County, 1890, showing Gravesend overrun by Gotham’s hungry grid. Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division, The New York Public Library.

Once the English took over, of course, special favor fell upon the erstwhile Trojans of Gravesend. New Netherland became the Province of Yorkshire, split into three ridings. Gravesend was made the seat of the “West Ryding of Yorkshire upon Long Island,” which included all of Brooklyn, Staten Island, and part of Queens. Its tenure as an administrative capital lasted until 1683, when Kings County was formed. Remarkably, Gravesend would remain an independent town until 1894, when it was annexed by the city of Brooklyn, thus ending 250 years of independence. As for the fate and final resting place of Deborah Moody, it remains an enduring mystery. She appears to have died in 1658 or 1659. By some accounts she had become a Quaker herself and led a contingent of settlers to Monmouth County, New Jersey. Others claim she passed on peacefully, an elder matriarch in the town of her founding. It may well be that Moody rests—fitfully perhaps, what with the F train rumbling noisily overhead—in an unmarked grave in the cemetery that still occupies the southwest quadrant of her four-square grid, across the street from a construction company, Mama’s Restaurant Supply, and a place called Russian Shoppe. If this “dangerous woeman” ever had a headstone there, it has long been lost, stolen, or eroded to illegibility. Her four-square monument endures, however, defiant in a sea of change, a 350-year-old relic of a long-vanished world.27