CHAPTER 3

DEATH AND THE

PICTURESQUE

Let’s talk of graves, of worms, and epitaphs . . .

—SHAKESPEARE, RICHARD II

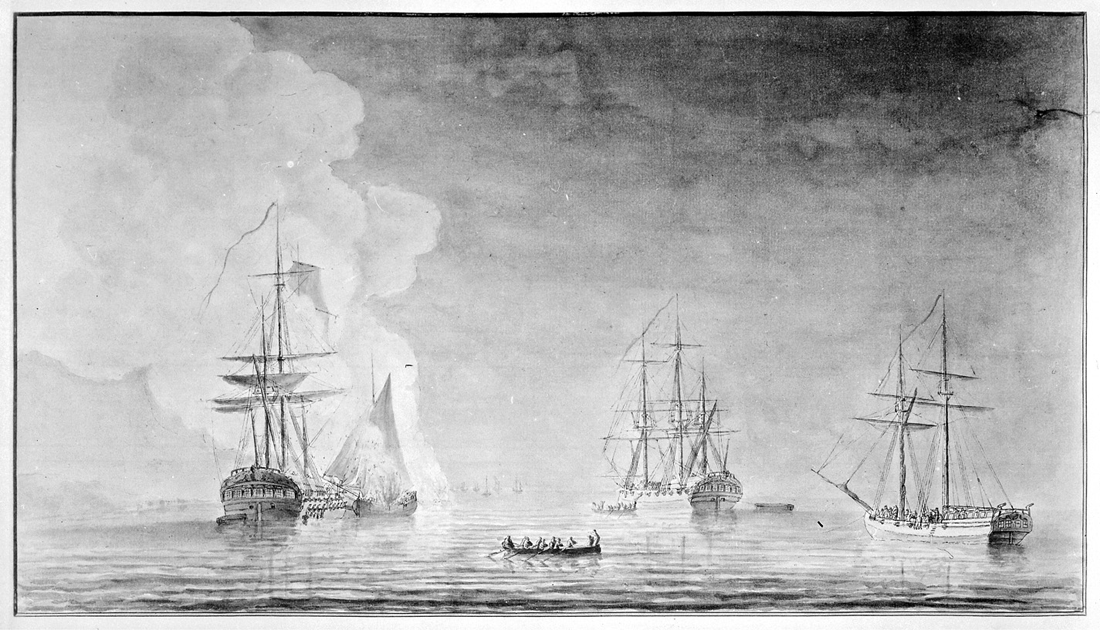

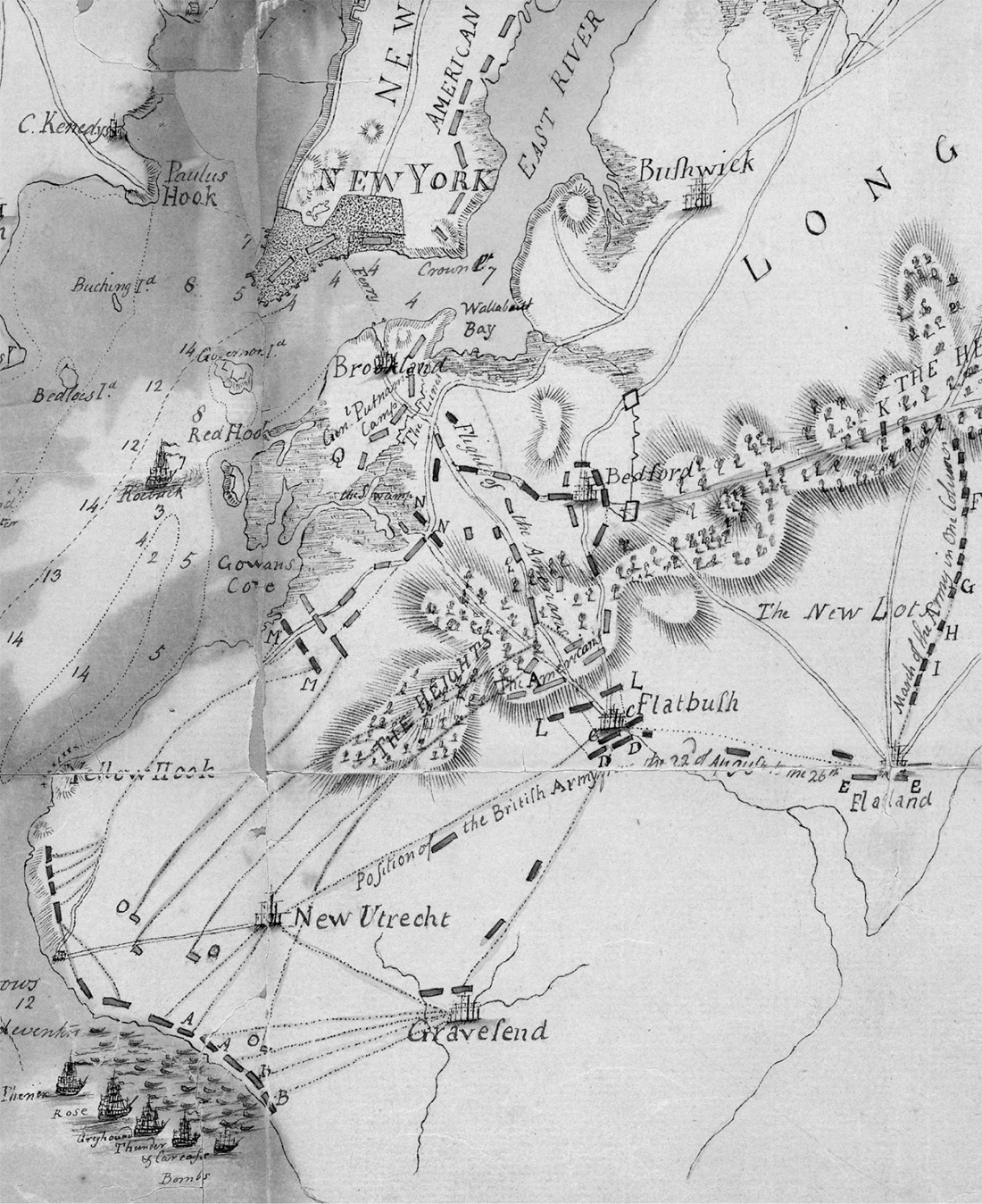

More than a century and a quarter would pass before the winds of history blew once more through Lady Deborah’s vernal town—winds that filled the sails of a much fiercer envoy from Albion: the largest and most powerful naval invading force since the Spanish Armada. It came on a balmy summer day in late June 1776—a fleet of 130 warships and nine thousand men under the command of British general William Howe. Dropping anchor off Sandy Hook, just weeks after the bloodshed of Bunker Hill, the fleet was paying no social call. “In the van were big British ships of the line,” writes David Hackett Fischer, “cleared for action with red gunports open, batteries run out, and huge white battle ensigns streaming in the breeze.” Then came transports loaded with fighting men, advancing “at a majestic pace, as if nothing in the world could stop them.” A private with the fated Maryland Line, Daniel McCurtin, watched in awe: “I thought all London was afloat,” he wrote. Howe’s ships then sailed through the Narrows to moor off Staten Island, where the troops disembarked. They were soon joined by an even larger force led by Howe’s older brother, Admiral Richard Howe. By the third week of August nearly 500 ships and 30,000 soldiers had arrived to put down the American rebels—until then “the largest projection of seaborne power,” writes Fischer, “ever attempted by a European state.”1

The gathered storm made landfall at Brooklyn. On the morning of August 22, flatboats packed with 4,000 British regulars under the command of General James Grant were launched from Staten Island, landing near Fort Hamilton—a place then known as Denyse’s Ferry. A second force led by Sir Henry Clinton rowed into Graves-end Bay, coming ashore at De Bruyn’s landing—about the present intersection of Twentieth Avenue and Twentieth Drive (where Fred Trump would one day build hundreds of homes on filled land). By noon some 15,000 troops had arrived, under the protective cover of battery fire from a phalanx of warships—the HMS Rainbow, Phoenix, Rose, Thunder, and Greyhound.2 The guns sent a wave of fear over the land. Farmers fled with their livestock, crowding country lanes ahead of the troops. Slumbering villages were awakened with a jolt. General Howe established his headquarters at New Utrecht, Lord Cornwallis at Gravesend. From there, Hessian colonel Carl von Donop was dispatched with his grenadiers to a position at Flatbush, where they skirmished with a band of colonists just south of the present Dutch Reformed Church. He was soon joined by additional Hessian and British brigades led by Wilhelm von Knyphausen and Philip de Heister. There were now 22,000 enemy troops on the ground; Kings County’s population had quadrupled in a matter of days. The infant American nation, having boldly declared its independence not two months before, was about to have its mettle tested. Major General George Washington’s ragtag army barely numbered 8,000 men—“imperfectly organized, insufficiently equipped, largely composed of unreliable militia, without adequate artillery, and without any cavalry.”3 Gathered against them was the world’s most proficient, best-equipped fighting force. The Declaration of Independence had been signed in ink in Philadelphia; it would now be signed in blood.

James Wallace, The Phoenix and the Rose engaged by the Enemy’s Fire ships and Galleys on the 16 August, 1776, engraved by Dominic Serres, 1778. National Archives at College Park, George Washington Bicentennial Commission Series (Record Group 148).

As night fell on August 26, American militiamen on the hills above Flatbush—the great glacial moraine running from the Narrows to Jamaica and beyond, a “natural breastwork” that was Washington’s first line of defense—could plainly see what lay in store for them.4 From the “impenetrable shadow of the woods which crowned the summit and slopes,” wrote Henry Stiles, “these few regiments of raw, undisciplined troops awaited the coming of their foe, whose tents and camp-fires stretched along the plain beneath them, in an unbroken line, from Gravesend to Flatlands.”5 Shortly before nine o’clock, the summer skies nearly dark, Howe and his generals—Clinton, Lord Percy, and Lord Cornwallis—made their move. De Heister was ordered to the Flatbush pass, and Grant dispatched to head north from the Narrows to engage the American right flank at Gowanus. Both were mere diversions; for Howe’s real objective—the plan was actually Clinton’s, accepted only reluctantly by his superior—was to send his main army through the unguarded easternmost pass over the morainal ridge at Jamaica. The troops, bivouacked along the Kings Highway, withdrew quietly, banking their fires and leaving tents in place. Thus were Washington’s spies tricked, for all through the night the enemy camp had “every appearance of actual occupation.” All seemed quiet on the southern front.

It was, of course, anything but. With the summer sky now finally dark, Clinton’s battalion of light infantry set out for the village of New Lots, followed closely by Percy, Cornwallis, and Howe with the main force of some 10,000 troops and fourteen pieces of field artillery. At about midnight, just beyond the Flatbush road (Church Avenue), they struck off on a northeast bearing, moving ghost-like over field and forest “so silently that their footfalls could scarcely be heard at ten rods’ distance.”6 Two miles by the crow, at a roadhouse called the Rising Sun (present junction of Broadway and Jamaica Avenue), the army swung to the left and began ascending the terminal moraine. Nowhere along the route did they encounter resistance. Clinton had anticipated at least a skirmish as the men crossed a soggy bottom by Keuter’s Hook (the head of Fresh Creek, near today’s Betsy Head Memorial Playground). “To his surprise, the place was found to be entirely unoccupied,” wrote Stiles, “and the country open to the base of the Bushwick hills.” Nor did anyone confront them on the Jamaica Pass—“a winding defile, admirably calculated for defence”—where the British expected a sharp fight. By dawn Clinton and his men were in full possession of the high ground. From there they moved swiftly on to the village of Bedford, now but a stone’s throw from the Continental units still hopelessly skirmishing with de Heister’s Hessians at the Flatbush pass. Thus was the great trap sprung: Howe had encircled the Americans from behind. General John Sullivan, Washington’s junior commander on Long Island, had suspected the British might do just this, but nonetheless was so duped by Howe’s feints at Gowanus and Flatbush that he sent no patrols to guard his left flank. “Fatal mistake!” exclaimed Stiles; “The battle was lost before it had been begun.” It was Hannibal minus the elephants. The Americans, like the Romans, were blindsided.7

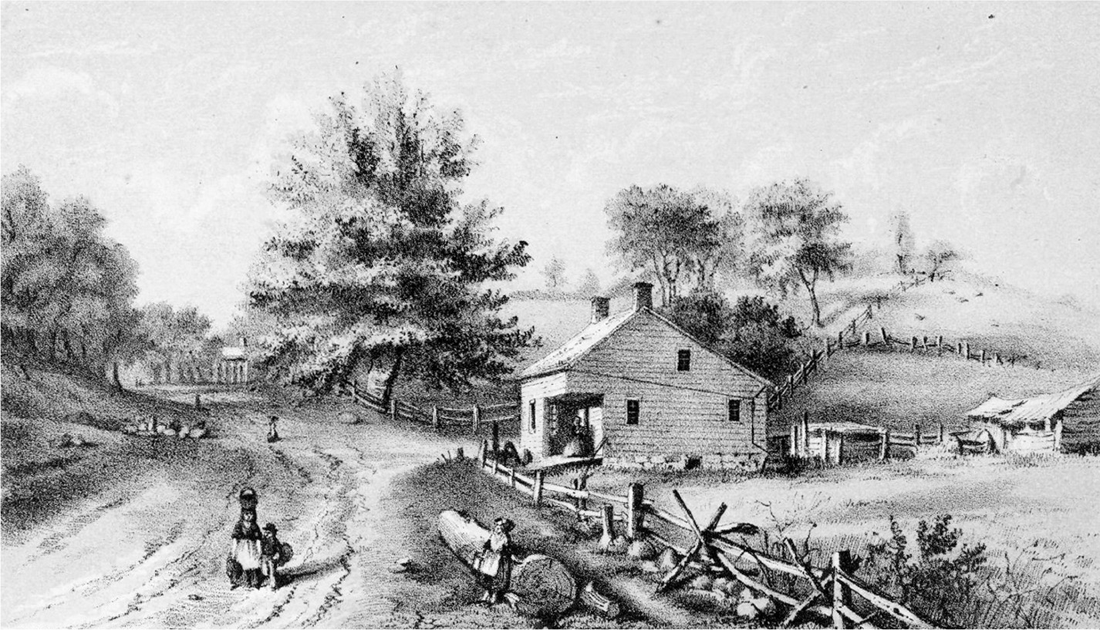

Hayward and Lepine, Battle Pass, Valley Grove, c. 1866. Brooklyn Museum, Dick S. Ramsay Fund.

If the battle was effectively over, the bloodshed had just begun. While Clinton’s army was encircling the Americans from behind, Grant marched some 5,000 men from the Narrows east to the New Utrecht Road—today’s Eighteenth Avenue—turning north onto Martense Lane for the Gowanus Heights. The diversionary maneuver was to become an all-out assault at the sound of Clinton’s signal cannon. Just before midnight, guards from a Pennsylvania regiment led by Colonel Samuel Atlee spotted British soldiers raiding a watermelon patch near a tavern known as the Red Lion Inn. The guards fired on the interlopers from the building, which of course immediately gave away the American front line. Grant then dispatched several hundred troops to attack the tavern, which stood at a sharp bend in the old Gowanus Road at Martense Lane (about where the garage and shops of Green-Wood Cemetery are located today near Fourth Avenue and Thirty-Fifth Street). Informed of this development, General Israel Putnam—Washington’s senior commander on Long Island—ordered Brigadier General Lord Stirling to check the British advance. Stirling grabbed two regiments nearest the action—one from Delaware under the command of Colonel John Hazlet and Colonel William Smallwood’s First Maryland Regiment, mustered at Baltimore and Annapolis and led that day by Major Mordecai Gist. Shortly after sunrise, Stirling’s men ran into Atlee’s retreating Pennsylvanians about a half mile north of the Red Lion; not far behind them the British were in hot pursuit. Stirling positioned his 1,500 troops in a long thin line from the marshy flats of Gowanus Bay up the crest of the hills then known as “The Heights of Guana” (running roughly from Third Avenue and Twenty-Third Street east to today’s Slope Park at Sixth Avenue and Nineteenth Street). The forces clashed all morning, yet Grant made no bold forward move.

He was waiting, of course, for the signal that Clinton and the main British army had gained the rebel rear. When it came, Grant charged forward while Cornwallis’s grenadiers—having routed the Americans fleeing the Hessian assault at Flatbush pass—swept down from the northeast. Stirling was a cornered rat. He ordered most of his troops to evacuate through the Gowanus marshes, while he and the ten Maryland companies unleashed a furious series of assaults on the British grenadiers. “It was Stirling’s hope,” writes historian James L. Nelson, “that the Marylanders could both cover the men’s retreat and fight their way to safety.”8 They accomplished the first, if barely, a delaying action that saved hundreds of fellow soldiers from certain death or capture. Again and again the Marylanders flung themselves at the British, who were fortified in an old stone farmhouse—the 1699 Vecht-Cortelyou house, reconstructed in nearby Washington Park by Robert Moses (as a restroom) and today the Old Stone House Museum. They were checked mercilessly by a volley of cannon grape. And yet they persisted, closing ranks and even briefly capturing the stronghold before being repelled again.

Detail from A plan of New York Island, part of Long Island, Staten Island & east New Jersey, with a particular description of the engagement on the woody heights of Long Island . . . on the 27th of August 1776, William Faden, 1776. Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division, The New York Public Library.

As the battle unfolded, Washington watched helplessly from a redoubt just to the north at Fort Ponkiesberg, located about where Trader Joe’s is today at 130 Court Street in Cobble Hill (a bronze tablet on the former South Brooklyn Savings Institution marks the spot). At last, with most of his men safely across the creek and en route to Brooklyn Heights, Stirling ordered the Marylanders to fall back and seek shelter as best they could behind American lines. Many never made it. Casualty estimates have been wildly exaggerated over the years, but of the 800 or so men of the First Maryland Regiment—Smallwood’s nine companies and the Seventh Independent Company led by Captain Edward Veazey—a total of about 260 men were killed, captured, or wounded, including 12 officers. New research has put the number of dead at between 25 and 142, far fewer than the traditional counts. Captain Veazey was among them, the highest-ranking officer to die in combat during the Battle of Brooklyn (though two other officers died later of wounds). Most were taken prisoner, which—for ordinary enlisted men—was itself effectively a death sentence. Though Major Gist made it to safety, General Sullivan was captured and Lord Stirling surrendered to the Hessians. Social class saved both men, who were treated “with great civility” by General Howe and even “dined with him almost every day.” The privates suffered a much worse fate. Many ended up in the pestilential holds of prison ships riding anchor in Wallabout Bay, where up to 11,000 American combatants would perish over the seven years of the Revolutionary War—more than were killed in all its land and sea battles combined. Thus did Brooklyn become the site of what Kenneth T. Jackson has called “the greatest American tragedy of the eighteenth century.”9

J. R. Smith, Guann’s near Fort Swift, 1817, a sketch of the Gowanus marshes where fighting between British grenadiers and the First Maryland Regiment occurred on August 16, 1776. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

The Battle of Brooklyn was the largest single fight of the American Revolution, the first after the nation declared its independence and the first that Washington himself commanded. It was a defeat, to be sure, but the best of sorts; for the Americans—and Washington—lived to fight another day. How and why this happened has long been debated. The British could easily have pushed on to storm the works at Brooklyn Heights, crushing the Continental Army and capturing its commander. It was only early afternoon when the Americans began retreating. For Howe, the course of action seemed clear. “Six good hours of daylight remained,” wrote Charles Francis Adams, “and, after demolishing the commands of Stirling and Sullivan, he should have followed up his success, striking at once and with all his force at Washington himself.” Had Howe done so, the war would have ended then and there, the feeble flame of American independence perhaps snuffed out for good. But Howe did not persist. He ordered his army instead to halt and make camp, so infuriating his officers that it “required repeated orders,” Howe reported, “to prevail on them to desist.” It is not clear why he did this, whether it was simple incompetence—“the dilatoriness and stupidity of the enemy,” as one of Washington’s generals put it—or because Howe wanted to prevent further bloodshed. Indeed, neither General William Howe nor his seafaring brother Richard were eager to fight a war against the American colonies; they agreed to serve only when pressed by George III. This had to do with their late elder sibling, George Augustus Howe, killed at Fort Ticonderoga during the French and Indian War. To honor the officer, the General Court of Massachusetts funded a memorial in Westminster Abbey. “The younger Howe brothers never forgot that kindness,” writes Nelson, “and it shaped their view toward the colonists, which was largely friendly and sympathetic.”10

The rebuilt c. 1699 Vecht-Cortelyou house (Old Stone House) in Washington Park, 1940. Historic American Buildings Survey photograph by Stanley P. Mixon. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

That the Americans lived to fight another day was also due to good luck—“almost miraculous good-luck,” as Adams put it—involving two providential turns in weather. The first was a change in winds. The prevailing southwest wind typical of late summer in New York would have easily carried the British ships of the line into the East River, cutting Washington’s army in half and marooning him on Long Island. But as the battle got under way, the wind began blowing from the northeast. Against this (and a stiff outgoing tide), the fleet of heavy warships could only struggle in vain. Then came the rain. On the morning after the battle the sky was “lowering and heavy,” according to Stiles, “with masses of vapor which hung like a funeral-pall over sea and land.” A drenching rain kept men on both sides in their tents and trenches. The fog persisted the following day, August 29, giving Washington the cover he needed to begin evacuating his troops. That night some 9,000 men and arms were moved across the East River in boats crewed by a regiment of sailors and fishermen from Marblehead, Massachusetts—a brilliantly executed maneuver that saved Washington and his army. Howe learned of the mass evacuation from a slave informant sent by a Tory sympathizer, but hours too late; for the emissary was mistakenly dispatched to a unit of Hessians, who couldn’t understand what he was saying—they spoke no English—and so detained him until daybreak. By then Washington was long gone. The American cause was still alive.11

The Battle of Brooklyn has long been a hushed chapter in America’s founding story—a “strange military fiasco,” as Adams called it, that never quite fit the glowing national narrative of God-sped exceptionalism. It was worse than a mere defeat, for rather than “inspiriting the defenders of freedom,” opined Nehemiah Cleaveland in 1847, “its consequences were depressing and disastrous; and the day was long thought of as a day of mistakes, if not disgrace.” That the whole mess was largely Washington’s fault also didn’t square with patriotic renderings of the sage and brilliant pater patriae. Washington’s decision to defend New York against Britannia’s mighty clenched fist was a strategic error—“hopeless from the start,” as Adams put it. What, he marveled, “could have induced Washington, with the meagre resources both in men and material at his command, to endeavor to hold New York against such an armament as he well knew the British could then bring to bear?” One of Washington’s more outspoken generals, Charles Lee (namesake of Fort Lee), had warned him that the water-bound city was indefensible against a naval power. “It is so encircled with deep navigable water, that whoever commands the sea must command the town.” Lee advised letting it all go. “I would have nothing to do with the islands to which you have been clinging so pertinaciously,” he wrote Washington; “I would give Mr. Howe a fee-simple of them.” Washington ignored the advice.12

Nor did the whole episode cast the future city of Brooklyn in very flattering light. Manhattan-bound antiquarian Peter Ross impugned the residents of “Kings and Queens” for the whole ugly episode; they, unlike their evidently more patriotic betters across the river, “remained callous to the slogan of Liberty” and cared less “whether King or Congress reigned.” Even Brooklyn stalwart Henry Stiles had to admit that “the people of Kings County seem to have viewed the approaching storm with perfect indifference,” for in them “fear of pecuniary loss and personal inconvenience quite outweighed the more generous impulses of patriotism.” The charges were not unfounded. Loyalist sympathies were strong in Kings County—not only in the old English settlement of Gravesend but all across the outwash plain. It was a trio of local Loyalists who guided the British army from Flatlands on the fateful night of August 27, after all. And unlike the patriotic lads from Maryland, Pennsylvania, and Massachusetts, most of the Kings County militia—including commanding officer Colonel Nicholas Cowenhoven—defected to the British on Staten Island or simply hid from service. Without such friends “even Howe’s army,” Ross charged, “could not have landed in triumph.”13

All this has long obscured the Battle of Brooklyn, effectively erasing it from landscape and collective memory alike. Its stain of failure has even eroded appraisals of the strategic importance of the Marylanders’ action on that fateful day. In a damning 1957 report to Congress, the National Park Service concluded that the rearguard action of the Marylanders saved only about 700 men at best, did little to restrain General Grant (“cautious by training” in any case), and only briefly sidetracked a small number of enemy troops—“perhaps 3,000 British and Hessians out of a total force of some 19,000 men.” The battle was already lost (though the soldiers had no idea of this); all the Marylanders did was snatch “brief glory from the jaws of imminent disaster.” In other words, they sacrificed their lives for nothing. Worse, the Park Service concluded that the Marylanders’ actions were “not of national significance” and thus unworthy of a monument. “Neither for its influence on the course of the battle, nor as a unique example of heroic military gallantry,” the report opined, were the events at Gowanus “comparable to the ‘matchless’ significance accorded national recognition at Saratoga and Yorktown Battlefields, and at Independence Hall.” Brooklyn’s great moment of Revolutionary glory was thus dismissed as misguided boosterism.14

It has long been assumed that the Marylanders felled in the fighting of 1776 were buried together in a mass grave, the finding of which—Brooklyn’s Holy Grail—has preoccupied history buffs for well over 150 years now. The story was propagated by an imaginative antiquarian named Thomas Warren Field, whose 549-page treatise on the Battle of Brooklyn was published in 1869. Moved perhaps by patriotic sentiment in the wake of the Civil War, Field wrote with every stop pulled on his rhetorical organ. “Artillery ploughed their fast-thinning ranks,” he dirged of the Marylanders, “with the awful bolts of war; infantry poured its volleys of musket-balls, in almost solid sheets of lead upon them; and, from the adjacent hills, the deadly Hessian yagers sent swift messengers of death into many a manly form.” And yet the brave lads were undaunted, closing ranks and turning “their stern young faces to their country’s foe.” All that’s missing from Field’s narrative is Moses on high, arms uplifted, speeding the Israelites to victory. Two hundred pages into his tale, Field turns to the fate of the Maryland dead, confiding that “on shore of Gowanus Bay sleep the remains of this noble band.” The fallen were interred on “a little island of dry ground” on the farm of Adrian Van Brunt, who “consecrated the spot for the sacred deposit” (Van Brunt actually did not buy the Staats farm for another decade, but we’ll let that pass). According to Field, this knoll was situated just east of Third Avenue between Seventh and Eighth streets. To its slopes the dead were carried and “laid beneath its sod, after the storm of battle had swept by.” Anticipating skepticism, Field hastily calls in his sole source: “Tradition says that all the dead of the Maryland and Delaware battalions who fell on and near the meadow were buried in this miniature island, which promised at that day the seclusion and sacred quiet which befit . . . the heroic dead.”15

Like any good fable, Field’s narrative rests partly on a foundation of truth. It is correct that much of the fighting on the morning of August 27 took place in and around the Gowanus tidal marshes—not an ideal place to bury bodies. It stands to reason that any interments afterward would have occurred on higher dry ground. And Revolutionary-era maps do show one or two small hummocks rising above the marsh in precisely the area delineated by Field (roughly a quarter mile southwest of the Vecht-Cortelyou house, where many of the casualties took place). Moreover, this elevated ground had long been used as a burial place. John Van Brunt, whose father purchased the Staats farm in 1786, recalled seeing graves there as a youth, some marked with headstones and others evident only by mounded earth. The knoll and its old cemetery were left intact by the Van Brunt family, as some of their number were buried there. Ultimately, however, the hummock fell before the “remorseless surveyor’s lines” of urban growth. No matter how altered, it would always be hallowed ground. “The very dust of those streets is sacred,” exclaimed Field. “And our busy hum of commerce, our grading of city lots, our speculations in houses reared on the scenes of such noble valor, and over the mouldering forms of these young heroes, seem almost a sacrilege.”16

Field’s account was effectively cast in stone when Henry R. Stiles retold it almost verbatim in his monumental, two-volume History of the City of Brooklyn, still the most expansive—if frequently inaccurate—opus ever written about the place. In less than a generation, the mass-grave story had firmly become part of the canon of New York City history. Few doubted its veracity, though the persistent lack of evidence should have given pause. When a tradition is compelling enough, “evidence” of its truth is often willed into being. As Gowanus urbanized in the 1890s, the occasional grave or human bones unearthed by grading and excavation were invariably hailed as proof that the Marylanders were in the ’hood. A 1906 New York Herald piece claimed, without a shred of evidence, that the grave site of the Marylanders was destroyed when Third Avenue was cut through the old Van Brunt farm around 1854—a time when “burial trenches . . . still showed plainly” on the east side of the new thoroughfare. Foundation work for the apartment buildings at 423–427 Third Avenue revealed an array of bone sets “laid out in regular, or military, order.” More human remains were discovered across Third Avenue some years later during construction of the Collyer Printing plant.17

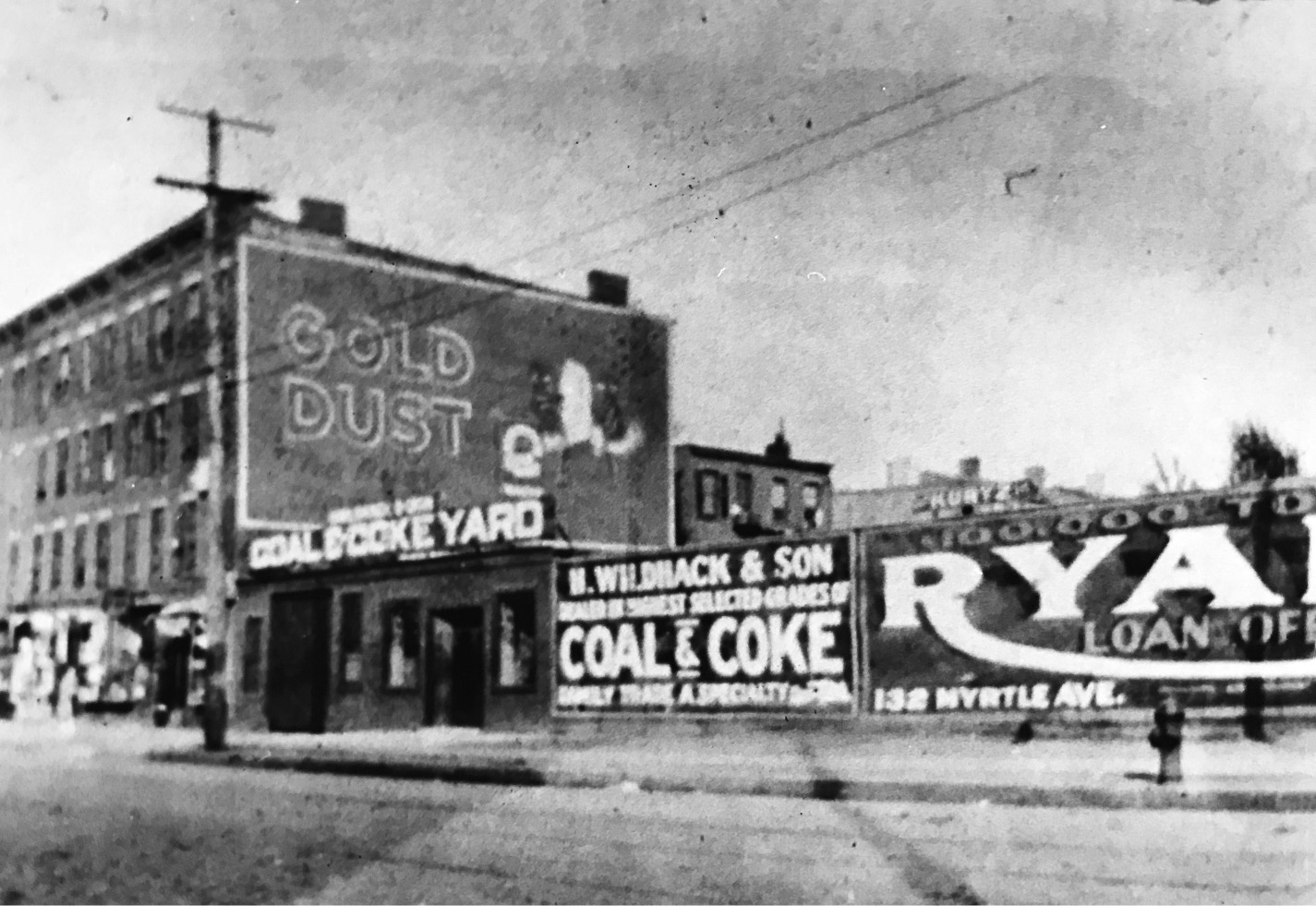

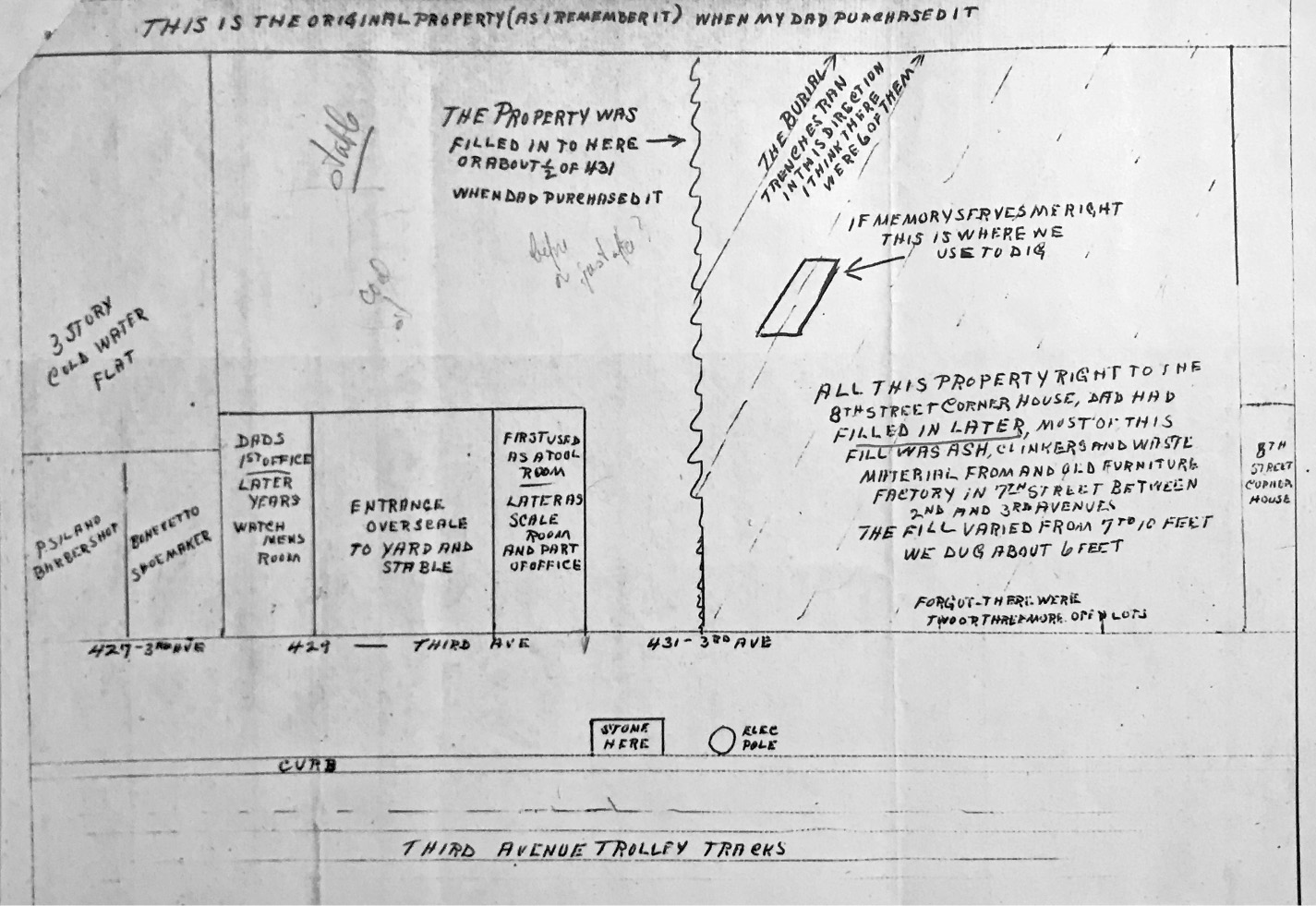

These discoveries helped launch an effort to commemorate the fallen troops. In early 1897 a stone tablet with inlaid bronze lettering was commissioned from the Yale and Towne Company and set in the sidewalk at 429 Third Avenue (paid for with leftover funds raised for the Maryland Monument in Prospect Park). Ironically, the slab was itself later buried—possibly when Third Avenue was widened or repaved in 1915—and thus lost underground just like the men it recalled. By then, the adjacent lots were in the hands of a coal dealer memorably named Henry Wildhack. A German immigrant, Wildhack purchased 429 Third Avenue in 1905 and the adjacent parcel (431) several years later. Both were vacant, the latter still at its original grade seven or eight feet below the street. Wildhack was a history buff and breathed new life into the Marylander story. As he related to the Brooklyn Eagle in 1910, a series of graves were “plainly visible” when he first bought the property. “The soldiers had been buried in about fifteen trenches,” he recalled, “each about a hundred feet long and extending diagonally from Third avenue to 8th street, in a southeasterly direction.” Wildhack tried to persuade city officials to buy the lots for a memorial, but failed and ultimately filled both to street grade. If the hapless Marylanders were ever under this land, they were now buried again, this time beneath an inglorious blanket of clinkers and ash. Wildhack’s son confirmed much of this account in an interview forty-five years later. He recalled “playing about the burial trenches . . . as a boy of ten or twelve, and digging through the crest of one of the mounds in the back part of the lot at 431.” There, “bones and miscellaneous material” were found. Wildhack, Jr., recalled the grave mounds being “three or four feet wide,” each “six or seven feet from the other.” He even drew a sketch map of the site and array of mounds.18

Henry Wildhack, Jr., with the long-vanished Maryland Regiment tablet at 429 Third Avenue, c. 1910. James A. Kelly Local History Collection, Brooklyn College Library Archives and Special Collections.

This was, for many, proof positive of the mass-grave theory. After Wildhack’s company closed in 1931, a victim of the Great Depression, the property was acquired by a manufacturer of Red Devil paints—the Technical Color and Chemical Works. The former coal yard was excavated to accommodate several concrete-lined tanks for pigments, lacquers, and thinners. But the tanks extended only seven or eight feet below grade, so it is unlikely that they would have disturbed anything from the Revolutionary era. Indeed, the excavating contractor reported finding no bones or artifacts; he was probably only removing Wildhack’s old fill. It wasn’t until January 1957 that the first serious archaeological study of the presumed burial ground was made—directed by Columbia University anthropologist Richard B. Woodbury and his graduate student Robert C. Suggs. Supervising the work was Frank Barnes, author of the aforementioned National Park Service report, and James A. Kelly, a schoolteacher and former vaudeville actor whom Mayor Fiorello La Guardia appointed Brooklyn’s first borough historian in 1944. Three days into the work, the team had excavated several large pits in the cellar of the former paint factory. They found nothing of value. The search was expanded to include backyards along Third Avenue, which were excavated to a depth of fifteen feet. Still no Marylanders. This was especially exasperating to Kelly, a Gowanus kid who grew up on stories of the lost soldiers. “I can’t understand it,” he reportedly said; “they should have been here.”19

Wildhack coal and coke yard, c. 1910. James A. Kelly Local History Collection, Brooklyn College Library Archives and Special Collections.

That frustrated conviction was because Kelly, like Wildhack and many others before and after, took the mass-grave account as gospel truth, when in fact it was based largely on hearsay and folklore. Field, architect of the tale, had conflated John Van Brunt’s confused memories of the Staats family cemetery on the meadow island with his recollection that, according to family tradition, “it had been the burial place of American soldiers who fell in the battle of L. I.” Field leaped to the conclusion that not only must a mass grave of Marylanders exist, but it must have been on the little knoll depicted on battle maps as part of the old Staats farm. To complicate matters further, there were several old graveyards in this area—including the Van Brunt family’s own plot at about Eighth Street and Third Avenue and a slave burial ground close by. Though family members in the Van Brunt cemetery were later exhumed, those buried in the other plots were likely not—especially not if they were “the servile sons of Africa,” as Field put it. These graves may explain the bones found now and then as streets were graded and foundations excavated. Some may even have been the remains of fallen colonial fighters. They were not, however, evidence of a mass grave of battlefield dead.

There are several reasons why the mass-burial story is almost certainly false. First, we know from multiple accounts that the fighting in Gowanus on August 27 ranged over a very large area—from the watermelon patch at the Red Lion Inn all the way north to the Vecht-Cortelyou house, a distance of nearly two miles. That ten companies of 800 Marylanders spent the entire chaotic morning glued together as a single unit over this span of ground is preposterous. This was guerrilla warfare, at least on the part of the Americans. Smallwood’s Maryland companies split up and converged and ultimately “broke up into separate groups near the close of the battle.” The combat dead would therefore have been scattered all about, not clustered in a group. Of course, bodies could have been moved later to a single burial site. But this does not square with either reason or British battlefield practice at the time. Would soldiers in the thick of a hot fight be taken from the front to haul corpses through field and swamp so that men who had just tried to kill them could repose in a neat array? Not likely. As Hunter College anthropologist William J. Parry explained in a 2017 research paper, “The British were distracted both by the construction of siege works, and by heavy rain.” The rain, as we have seen, fell for two full days after the battle, after which “both sides withdrew from the battlefield.” There was neither the time nor the weather for a coordinated mass interment.20

Henry Wildhack, Jr.’s 1957 sketch map of his father’s coal and coke yard as it was fifty years earlier. James A. Kelly Local History Collection, Brooklyn College Library Archives and Special Collections.

Nor was there the will. Until the Civil War, battlefield dead were rarely “gathered in formal cemeteries, or marked or recorded,” notes Parry, especially enemy dead. They may not have even been buried at all—at least at first. Corpses were often deliberately left where they fell to rot, and could remain there for weeks or months. Ambrose Serle, General William Howe’s private secretary, noted on September 3 that “the Woods near Brookland are so noisome with the Stench of the dead Bodies of the Rebels . . . that they are quite inaccessible.” Decomposing corpses were reported in the field as late as June 1777, a full ten months after the Battle of Brooklyn. And if the bodies of the dead were committed to the ground, it was usually done with great haste and minimal decorum. Graves were typically shallow and unmarked, and thus easily disturbed by groundwater, frost heaving, or animals. In the aftermath of the Battle of White Plains in October 1776, bodies of the dead had been “so slightly buried,” observed Connecticut private Joseph Plumb Martin, “that the dogs or hogs, or both, had dug them out of the ground . . . sculls and other bones and hair were scattered about the place.” Given the heat and rain of late August 1776, the corpses would have putrefied rapidly, making it all but certain that the fallen Marylanders “would have been buried as close as possible to where they fell,” writes Parry, “with the least possible handling.” The likelihood that the rotting remains would have been carried from afar for burial in an orderly array is virtually nil. If—and wherever—they were buried, who might have carried out the grim work? Locals pressed into service by the British, most likely, or labor battalions of former slaves who joined the British side in exchange for the freedom promised by Virginia governor Lord Dunmore’s “Emancipation Proclamation” of November 1775. What about the mounds and trenches that Henry Wildhack, Jr., played amidst as a boy? Parry suggests that these may have been the traces of a short-lived road, Hammond Avenue, one of four new thoroughfares proposed in 1839 by a committee on streets and squares. Named after Brooklyn street commissioner A. G. Hammond, the road began at Atlantic Avenue and Smith Street and ran south to Twenty-Third Street at Green-Wood Cemetery—a trajectory that took it across the Wildhack lots in precisely the same location and orientation of the presumed burial trenches. Though it’s unclear how much of Hammond Avenue was actually built, some of it was probably staked and graded before being closed and struck from maps—in March 1846—by the Brooklyn Common Council.21

In the end, the tale of the Marylanders’ mass burial was a largely manufactured one—an example of what historian Eric Hobsbawm has called an “invented tradition.”22 Typically formed about a kernel of historical truth, invented traditions enlarge or distort the past to meet specific political needs. They almost always appear in times of rapid social change, especially when a dominant group feels threatened by forces beyond its control. The mass-grave story was simply not part of Brooklyn history until Stiles popularized Field’s account in 1867, at a time of unprecedented national trauma and mourning in the United States. No chronicler beforehand mentions a word of the collective burial—an astonishing omission in light of the story’s eventual grip on the public imagination. By the end of the nineteenth century, interest in the Marylanders had soared. Keyword analysis of the Brooklyn Eagle newspaper archives shows a surge of articles on the topic between 1890 and 1915. This was, not coincidentally, a period of convulsive transformation in both New York City and America at large. In those years some twenty million immigrants entered the United States, mostly from the impoverished countries of southern, central, and eastern Europe. The vastly different religious, linguistic, and cultural backgrounds of these people—Russians, Slavs, shtetlekh Jews from the Pale of Settlement, Italian peasants from the Mezzogiorno (including some of my own ancestors)—caused tremendous anxiety among native-born Americans, and the Anglo-Dutch “Old Brooklynites” were no exception: the charter culture of the United States, they feared, would soon be smothered. The antidote? Recover all traces of the hallowed past to recharge and renew it as a means of inoculating one’s heritage against the alien Other. If this required the embroidery or embellishment of traditions—or even their outright fabrication—so be it.

Invented or not, romantic tales are hard to kill—especially those about the dead. By 2010, with the Wildhack lots newly capped by a five-story condominium, the search for the Marylanders shifted to a nearby site—a vacant block-wide parcel between Eighth and Ninth streets just off Third Avenue. That this site might at last be the fabled mass burial ground was a view aggressively championed by two neighborhood activists—Robert Furman of the Brooklyn Preservation Council and Eymund Diegel, a South African–born urban planner with experience in remote sensing and digital cartography. They had a strong ally right next door, literally: the Michael A. Rawley, Jr. American Legion Post at 193 Ninth Street, whose members were understandably thrilled at the prospect of a major Revolutionary War landmark at their doorstep. Furman and Diegel proposed setting aside the parcel as open space, an effort that received extensive press coverage. In August 2012 the New York Times ran a feature article on this latest quest for the lost Marylanders, describing the mass grave as “the archeological equivalent of the Golden City of El Dorado.” Not only would a park preserve the site for archaeological work, the pair argued, but it might help slow the snowballing gentrification of Gowanus—already a wild mix of collision shops, Pilates studios, and artisanal bakeries. “In their eyes,” wrote the Times, the parcel’s fate “will determine whether the neighborhood remains a low-rise middle ground that acts as a bridge between Carroll Gardens and Park Slope, or becomes an architectural island, full of the glossy towers . . . that have transformed the Williamsburg waterfront in recent years.”23

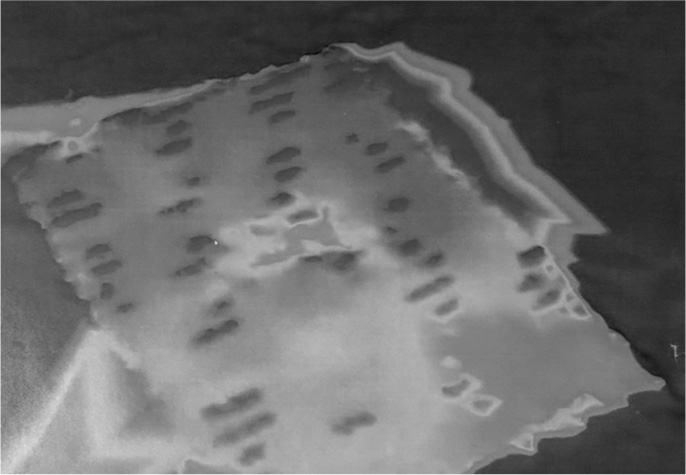

As often happens when passion runs ahead of reason (especially when an agenda of ulterior motives is involved), Furman and Diegel and their supporters began seeing the Marylanders everywhere. Diegel had been mapping lost streams around Gowanus using balloon-borne camera technology shared by a citizen science initiative, Public Lab, which he helped found after the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill. In July 2012 he and several volunteers lofted a camera—a “Canon SD 880 Hello Kitty camera strapped into a recycled organic carrot juice bottle,” as Diegel put it—above the Ninth Street parcel. One of his volunteers lay down on the concrete to provide comparative scale. Studying the photographs, Diegel detected a strange repetitive pattern of cracks in the concrete, aligned to a north-south axis and seeming to match the burial trenches described long ago by Henry Wildhack. As the Times put it, the cracks suggested to Diegel “that the ground underneath had been disturbed in a way that might be consistent with a grave site.”24 Far more convincing was a digital elevation model he subsequently produced with Jarlath O’Neil-Dunne of the University of Vermont, using a sophisticated remote-sensing technology known as LIDAR (Light Detecting and Ranging). By sending and receiving back a pulsed beam of laser light, this technology permits distances across a surface to be measured or “ranged” with extreme accuracy. Variations as small as a quarter of an inch can be detected, enabling cartographers to create highly detailed models of terrain or surface features. Diegel and O’Neil-Dunne used public-source LIDAR data to generate a color-coded elevation model that revealed what they described as “an intriguing pattern of human shaped bumps.” Of all the many sketches, maps, and drawings put forth over the decades in quest of the Marylanders, this is easily the most powerful and the most haunting, and it’s not clear why Diegel and Furman backgrounded it in favor of the somewhat clownish balloon-cam work.

Eymund Diegel (right) with his “Over My Dead Body” balloon-mapping team at the Ninth Street lot. Photograph by Sara Dabbs, 2012.

Propelled by such convincing imagery, the story of the search for the Marylanders spread far beyond Brooklyn. In June 2014 Diegel and his team were invited to present their study—cleverly titled “Over My Dead Body”—to President Barack Obama at Public Lab’s inaugural White House Maker Faire. They even sent a balloon camera aloft over the Rose Garden. By then, he and Furman had begun describing the Marylander site as “America’s First Veteran’s Cemetery” and even planned an international design competition for a commemorative park—the Marylander Green—which would be linked to the Old Stone House at Washington Park and other area sites via a Gowanus Canal Revolutionary Trail and Greenway. It was an admirable initiative, but one built on a shaky foundation. Nonetheless, Diegel and Furman drew many to their cause, including—of all people—the erstwhile captain of the Starship Enterprise, Patrick Stewart. The knighted actor’s enormous prestige and personal gravitas served as a public relations godsend. In February 2017, the actor led GQ reporter Caity Weaver to the vacant lot while regaling her with the tale of the ill-fated regiment (“sounding like a narrator,” she noted, “the History Channel could not afford”). “It’s worth making, I think, a bit of a fuss of,” he said.25

LIDAR model by Jarlath O’Neil-Dunne and Eymund Diegel of the Ninth Street lot, showing terrain microanomalies. Courtesy of Eymund Diegel.

And then it all came to an end. In May 2017 the New York City School Construction Authority bought the site for a proposed kindergarten at 168 Eighth Street. Within weeks, the State Historic Preservation Office formally requested an archaeological survey—a requirement for almost all city construction projects. A consulting firm was contracted, AKRF Associates of New York. Digging began at once. Eight trenches, evenly spaced across the site, were excavated to depths of seven to ten feet. At the eastern end of trench five several potentially significant features were uncovered—a brick cistern, a stone well, and a privy—along with evidence of a buried ground surface. These deserved greater study, and so that September the central portion of the site was further excavated—this time to as much as fourteen feet below the surface. The results were disappointing. The privy, well, and cistern, along with a plethora of other artifacts—filled post holes, old ash pits, iron pipe, broken liquor bottles, and burned animal bone (waste from an old ink factory on the site)—dated back only to the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Undisturbed subsoil was encountered close to the surface, meaning the site was never extensively filled. More to the point, “no evidence of human remains or grave shafts was observed anywhere within the Phase 2 work area,” according to the study’s lead archaeologist, Elizabeth D. Meade, making it “exceedingly unlikely that intact 18th century archeological sites or human remains are located on the project site.” Against cold, hard evidence like this even the most compelling tales must fall. Diegel’s LIDAR imagery, it turns out, revealed nothing more than pavement anomalies, while the pattern of cracks detected with the balloon-cam rig were likely just caused by rusted, swollen reinforcement bar in the concrete. And yet Diegel remains committed to the idea of a mass Marylander grave of some sort, even if not on the Ninth Street site. “I feel the jury is still out,” he told me recently; for even if a single mass burial site is unlikely, “there would still have been some piling up of bodies,” he says, “meaning probably several mass graves in soft marshy soil areas.”26

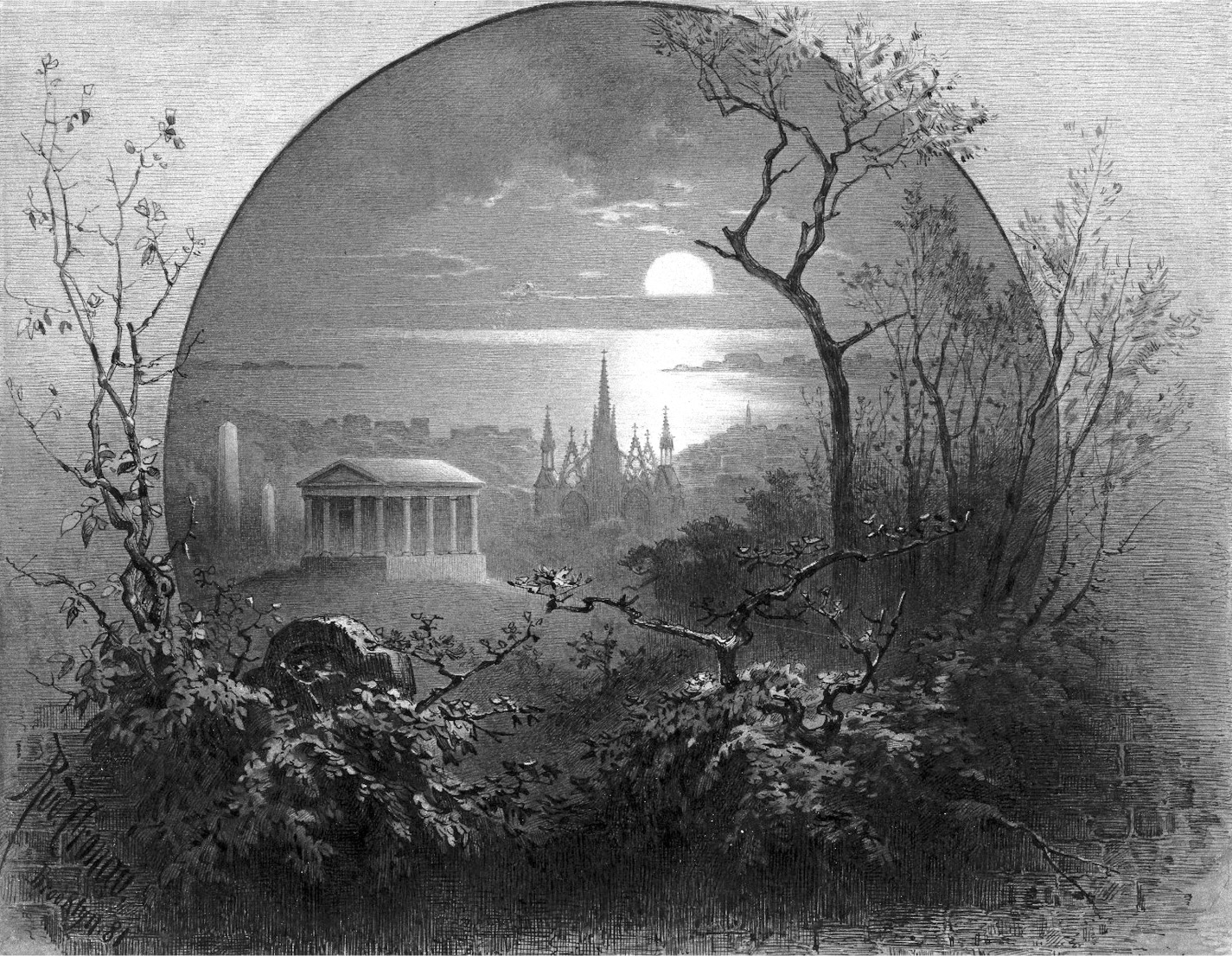

If the Maryland dead never found peace together in consecrated ground, consecrated ground ultimately came to them. For by the mid-nineteenth century much of the battlescape of August 1776 had been transformed into a vast burial ground. This “silent city of the dead,” christened Green-Wood Cemetery, was the third and greatest example of a Franco-American invention of the romantic era—the “rural” cemetery. Created a generation before the arrival of Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, it drew upon the same design tradition that would be used for Central and Prospect parks—the so-called English school of “landscape gardening” that formed in the early eighteenth century in reaction to the French neoclassical tradition. Theorists and practitioners like Lancelot “Capability” Brown (who waxed lyrical about the “capabilities” of an estate to potential clients) and his disciple Humphry Repton set about composing landscapes evocative of the romantic landscape paintings then in vogue—scenes of classical antiquity, idyllic ruins, and the Italian campagna by Claude Lorraine, Nicholas Poussin, and Salvatore Rosa. Garden design was turned on its head; the spatial discipline of the French baroque—rigid geometries, unyielding symmetry, anchored sightlines—fell in favor of a studied informality, a great tousling of form and space that emulated the seeming “chaos” of nature. The straight was made crooked, the smooth made rough. Terraces became hillocks; walls were replaced by the “ha-ha,” a trenched barrier tucked behind a berm from manor-house view. Trees, once planted in bosques and allées, were now set in scruffy clumps—“like dumplings,” snarked Norman T. Newton, “floating in a sea of sauce.” This was nature perfected for the enlightenment of man, or so its admirers thought.27

If such a curated rustic landscape so pleased the living, perhaps it could also comfort the dead—or at least those who mourned them. It was in France—at Père Lachaise Cemetery on the eastern outskirts of Paris—that this idea of eternity-in-a-garden first took form. Named after the father confessor of Louis XIV, Père Lachaise opened in 1804 as a secular alternative to the hideously overcrowded church burial grounds in the center of Paris. Far from the city and not consecrated by the Catholic Church, Père Lachaise languished at first. It was a clever marketing move—“seeding” the cemetery with the exhumed remains of two exalted Frenchmen, Molière and Jean de la Fontaine—that stoked interest in the place among the Paris elite. Within a generation, Père Lachaise had become the place to go when you went. Its grave roll is a catalog of French history—Balzac, Callas, Chopin, Proust, and Edith Piaf are all buried there (so are Oscar Wilde and American rocker Jim Morrison). It also became a popular pleasure ground, where families could picnic and promenade on Sundays among the illustrious dead. It was on the rural outskirts of Boston, about a mile west of Harvard Yard, that this French idea first took hold in America. Mount Auburn Cemetery was the brainchild of a Boston physician and botanist named Jacob Bigelow, who became a vocal advocate of modern “sepulture” after an 1820s revival of ad sanctos or churchyard burials in Boston. Prevailing medical theory at the time blamed a variety of dread diseases on the poisonous exhalations or “miasmas” thought to emanate from congested city graveyards. A rural cemetery not only offered a solution to a public health menace, but indulged Bigelow’s long-standing interest in trees and plants. It also reflected changing perceptions of death, less burdened now by Calvinist notions of worms and damnation—of “gloomy vaults and silent aisles,” as Washington Irving wrote of Westminster Abbey—and charged instead with a redemptive yearning to celebrate the lives and deeds of the deceased. Why, Irving asked in The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, “should we thus seek to clothe death with unnecessary terrors, and to spread horrors round the tomb of those we love? The grave should be surrounded by every thing that might inspire tenderness and veneration for the dead; or that might win the living to virtue.”28

Backed by the newly established Massachusetts Horticulture Society, Bigelow arranged the purchase of a seventy-two-acre woodland tract above the Charles River known as “Sweet Auburn.” There an “ornamented rural cemetery” was consecrated in September 1831, laid out by Bigelow himself and engineer Alexander Wadsworth. With its hills and dales and century-old trees, “Sweet Auburn” needed little to become a paragon of the picturesque. Here “the beauties of nature should, as far as possible, relieve from their repulsive features the tenements of the deceased,” Bigelow wrote, and, “at the same time, some consolation to survivors might be sought in gratifying . . . the last social and kindred instincts of our nature.” Of course, it would not do for Boston’s Brahmins to have such an exquisite place to spend eternity and not New Yorkers, whose city—even in the 1830s—had three times the population and tenfold the ambition of Boston. It was Henry E. Pierrepont, scion of Brooklyn’s most prominent family, who took up the cause on behalf of Gotham. Son of Hezekiah Pierrepont—creator of Brooklyn Heights—the younger Pierrepont visited Mount Auburn in 1832, returning “with the desire awakened that New York and Brooklyn should have a similar establishment . . . not unworthy of their greatness.” He spent the following year in Europe visiting the historic cemeteries and campi santi of France and Italy. While away, Pierrepont was appointed chair of the Board of Commissioners charged with laying out streets for the new city of Brooklyn. It was in this role, ironically, as Brooklyn’s master of the urban grid, that Pierrepont gained the authority to set aside land for a cemetery. He initially tried to buy the same Van Brunt farm later said to hold the fallen Marylanders. When the Van Brunts refused to sell, Pierrepont looked instead to a sprawling tract of high ground just to the south, on the Heights of Guana that saw so much fighting in 1776. The land—“beautifully diversified by hill and valley” and encompassing “a variety and beauty of picturesque scenery . . . seldom to be met with in so small a compass”—included Kings County’s highest point, Mount Washington. Rising some 220 feet above sea level and affording spectacular views of the harbor and New York beyond, it would eventually be renamed Battle Hill.29

Rudolph Cronau, View from Greenwood Cemetery, Brooklyn, 1881. Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Gerold Wunderlich.

Pierrepont and a group of wellborn Brooklynites chartered their cemetery as a joint-stock corporation on April 11, 1838, and spent most of the next ten months wresting a 175-acre site from multiple, often avaricious, landowners. The grounds were very nearly called Necropolis. But the name was deemed too classical for a romantic landscape, and much too urban. After all, this was a rus to counter the fevered urbs. “Necropolis,” it was decided, “savours of art and classic refinement, rather than of feeling, and herein is our objection. A Necropolis should be an architectural establishment, not a shady forest. Besides, a Necropolis is a mere depository for dead bodies—ours is a Cemetery . . . a place of repose.” And so it was named Green-Wood instead, a landscape whose “visible associations,” wrote trustee David B. Douglas, “are intended to be exactly what its name implies—verdure, shade, ruralness, natural beauty; every thing, in short, in contrast with the glare, set form, fixed rule and fashion of the city.”30 A civil engineer who had cut his teeth on the Croton Aqueduct and the Brooklyn-Jamaica railroad, it was Douglas who oversaw the long work of coaxing a landscape garden from the wild Gowanus heights. It was the first expression in New York of an English landscape aesthetic—the picturesque—that would reach a zenith with the urban parks of the Olmsted era. Adumbrated by the English aesthetic theorists William Gilpin and Uvedale Price, the picturesque differed from the sublime or the beautiful by its emphasis on “roughness.” As Gilpin explained in a 1792 essay, picturesque design—on canvas or on the ground—required snapping the line of beauty, interrupting the “smoothness of the whole”:

Turn the lawn into a piece of broken ground: plant rugged oaks instead of flowering shrubs: break the edges of the walk: give it the rudeness of a road: mark it with wheel-tracks; and scatter around a few stones, and brush-wood; in a word, instead of making the whole smooth, make it rough; and you also make it picturesque.31

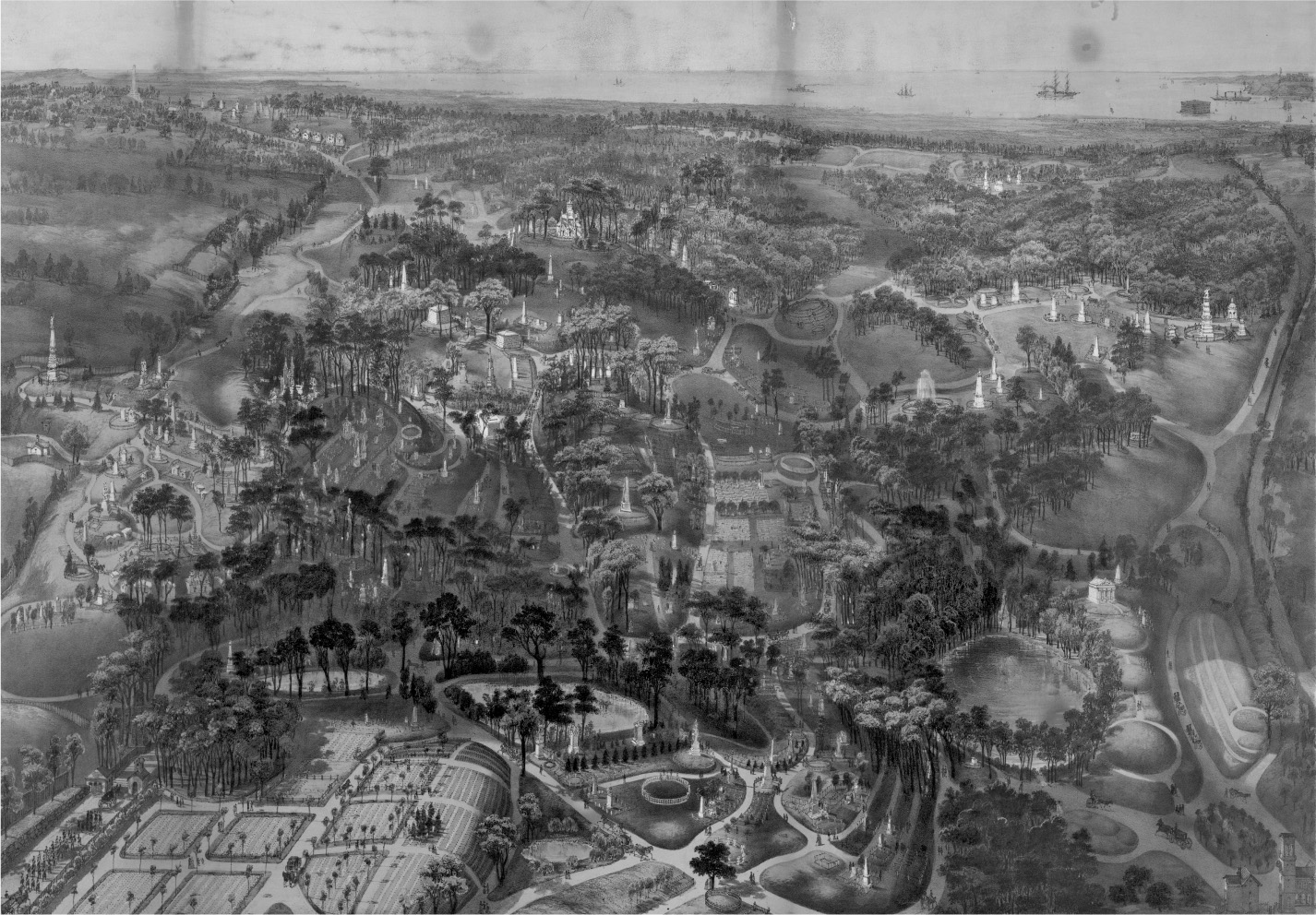

The first improvements at Green-Wood—a simple rail fence around the cemetery’s perimeter and a road “passing through its most interesting portions”—were made the summer of 1839. The first interment, of a man named John Hanna, came the following September. By then the cemetery’s metamorphosis was well under way. Writing in 1841, the pioneering plantsman and landscape designer Andrew Jackson Downing—America’s first authority on spatial improvement—predicted that Green-Wood would inevitably eclipse Mount Auburn as the greatest garden cemetery in the United States. “In size it is much larger,” he noted in the Gardener’s Magazine, “and if possible exceeds it in the diversity of surface, and especially in the grandeur of the views. Every advantage has been taken of the undulation of surface, and the fine groups, masses, and thickets of trees, in arranging the walks; and there can be no doubt, when this cemetery is completed, it will be one of the most unique in the world.” All told, Downing conjectured, America’s new rural cemeteries were “the first really elegant public gardens or promenades formed in this country” and “the only places . . . that can give an untravelled American any idea of the beauty of many of the public parks and gardens abroad.”32

As odd as it may sound to us, the rural cemeteries of Boston, Philadelphia, and New York were thronged from the start—not by the dead or their mourners but by the living, ordinary people yearning for trees and fresh air, an afternoon’s relief from the pressures and congestion of urban life. Once Green-Wood’s main road opened, on July 4, 1839, word got out fast that a place of great beauty “had been added to the scanty privileges of New York and Brooklyn,” related Cleaveland; “and Green-Wood soon became a place of considerable resort.” By the 1860s, only Niagara Falls was drawing more visitors annually than Green-Wood. Twenty years before Central Park, the cemetery was effectively New York’s first great urban playground. “Judging from the crowds of people in carriages, and on foot, which I find constantly thronging Green-wood and Mount Auburn,” Downing reported in the Horticulturalist, “I think it is plain enough how much our citizens, of all classes, would enjoy public parks on a similar scale.” Indeed, the immense popularity of Green-Wood and its predecessors—Mount Auburn and Philadelphia’s Laurel Hill Cemetery—would spark an urban parks revolution that, by the end of the century, profoundly transformed the form and structure of the American metropolis.33

If Brooklyn provided Manhattan a model for its greatest park, it received—in caskets and coffins—the isle’s illustrious dead. Many a Knickerbocker recoiled at the thought of spending eternity in the provinces, much as Mayor Ed Koch would cantankerously do a century later. When Trinity Church contemplated purchasing a large plot at Green-Wood, it nearly caused a riot among the congregation—native Manhattanites who were “shocked at the idea of being taken over the water, or of being buried anywhere except on that same rock-ribbed isle.” Instead, the church acquired a small burial ground on the Upper West Side (where Koch was buried in 2013). That changed soon enough; as Green-Wood’s fame spread, it became the location of choice for Gotham’s aristocracy to spend eternity. By 1842, lonely John Hanna had been joined by 133 other dead men and women. A decade later there were some 26,000 souls interred at Green-Wood, a peaceful population nearly equal to that of the Bronx and Queens at the time. This included fresh burials as well as “removals from other grounds,” among them members of the Van Brunt family interred atop their salt marsh knoll. If any men from the First Maryland were buried with the Van Brunts, they may well now also rest at Green-Wood—“Beneath the verdant and flowery sod,” Cleaveland rhapsodized in full Victorian mode; “beneath green and waving foliage—amid tranquil shades, where Nature weeps in all her dews, and sighs in every breeze, and chants a requiem by each warbling bird.”34

John Bachmann, Bird’s Eye View of Greenwood Cemetery, 1852. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.