CHAPTER 8

THE STEAMPUNK ORB

Verticality is such a risky business.

—COLSON WHITEHEAD, THE INTUITIONIST

The port metropolis once imagined for Gravesend—capital of a “blooming republic” that would stretch from the East River to Montauk Point—obviously never came to pass. But Deborah Moody’s old town was destined nonetheless to become a great city by the sea, even if the good woman and her pious votaries could hardly have approved of it. For Willem Kieft’s 1645 grant to the Massachusetts Bay émigrés included all of that seaside place later known far and wide as Conyne Eylandt—“rabbit island” in Dutch. The westernmost of a long chain of barrier islands between Long Island’s south shore and the Atlantic, it was part of the common lands of the town of Gravesend for over two hundred years. With a thick mane of brush and scored by tidal creeks, the lands were used by townsfolk for pasturing livestock, harvesting salt hay, and hunting waterfowl. Coney was then truly an island; one reached it by fording Coney Island Creek at low tide. Around 1830 a toll causeway was built over the channel—a southward extension of Gravesend’s main street, physically joining the old settlement to its future. Soon a small hotel—the Coney Island House—was erected to accommodate visitors. Within a few years a great circular tent pavilion had been built, followed by a wharf, another hotel, and several bathhouses. The trickle of visitors became a flow. On a balmy spring Sunday in 1847, some three hundred coaches and carriages passed through town on their way to the beach. The Gravesenders made a big show of condemning such “wholesale Sabbath-breaking,” but in private they rubbed their hands in glee. The world was knocking at the door.1

In short order, horsecars and a rail line—the Brooklyn, Bath and Coney Island Railroad—were ferrying carloads of passengers down from the growing city to the north. Around the terminal sprang up beer halls and bathing pavilions. Development quickly spread out from there, until “the entire beach front was thickly studded,” noted William H. Stillwell (namesake of Stillwell Avenue), “with these aspirants for public favor.” Iron piers were built to receive steamers from New York and New Jersey. Additional rail lines—the Culver and the Sea Beach—brought ever larger waves of New Yorkers to the beach. Vast bathing pavilions soon rose over the sands—Charles Feltman’s Ocean Pavilion, Bauer’s West Brighton Hotel, the Sea Beach Palace. Towering overhead was the tallest structure in the United States at the time—a three-hundred-foot observation tower recycled from the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia. By the 1880s, as many as 100,000 people would descend upon Coney Island on a summer day. Baptist or otherwise, the god of fortune had come to town. Gravesend’s common lands were now among the most valuable real estate on the Eastern Seaboard; leases brought in a rich bounty of rents and fees. The old settlement was soon “probably the wealthiest town in the State.” Long run by a peaceable gentry descended from the Moody crew, Gravesend was increasingly dominated by one of the more colorful figures in Brooklyn history—John Y. McKane. McKane was a native Gravesender of immigrant Irish stock, a carpenter and builder by trade. The man craved power. He ran successfully for town constable, and was soon made a commissioner of common lands and a Gravesend town supervisor. Before long McKane was also chief of police, commanding a force of 150 men, as well as president of the Town Board, Board of Health, Police Board, and Water Board—each “made up of the same five persons” and all nominated by McKane himself. He was the self-appointed king of Gravesend.2

Gravesend and Coney Island, 1873. From F. W. Beers Atlas of Long Island, New York. Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division, The New York Public Library.

McKane abused all this authority in full-blown Tammany fashion. He was especially adept at lining his pockets through shady deals involving the priceless common lands. Because he was town supervisor, every lease required his signature, which was forthcoming only after substantial sums passed into his hands. Though McKane deserves credit for building Coney Island’s first modern infrastructure, his administration was also responsible for turning a once-lovely place for a family outing into an unholy warren of gambling dens, whorehouses, and assorted other “cheap and shifty places where the quick-witted huckster caught the nimble dime and nickel of an ever growing clientele.” By the 1890s there were seven hundred saloons in Graves-end, half without a license and nearly all on the island proper. It was this “Sodom by the Sea” reputation that sequestered the gentry eastward in the clipped and staid Brighton Beach and Manhattan Beach hotels. Attempts to depose McKane always ended in failure and ruin. When a new law was passed mandating six election districts in Gravesend, he ingeniously used the town’s seventeenth-century pattern of radial lot lines to force a sliver of each district through the town hall, enabling him to make it a personal panopticon from which he could watch voters and intimidate them into casting ballots his way. Not until 1893 was McKane finally convicted of something that stuck—election fraud, alas—and sent up the Hudson to Sing Sing Prison. Gravesend was finally relieved of the Tammany thumb. But it had little time left itself: in 1894 the old town was annexed by the city of Brooklyn, ending 250 years of independence. The stage was now set for the rise of modern Coney Island. It would be dominated by a man every bit as ruthlessly ambitious as McKane—George C. Tilyou. Born in Manhattan but raised on Coney Island, where his parents ran the popular Surf House restaurant and bathing pavilion, Tilyou made a fortune brokering real estate when the Gravesend common lands were offered for sale in the 1880s. He caught the entertainment bug after a honeymoon trip to the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893. There at the Midway plaisance, Tilyou was enraptured by George Ferris’s colossal wheel, which he promptly tried to buy. Rebuffed, he commissioned instead a half-size replica—billing it nonetheless as the world’s largest. Bejeweled with hundreds of lightbulbs, Tilyou’s wheel quickly became the most popular attraction in Coney Island when it opened in 1894, paying for itself in a matter of months.3

But success in Coney Island required constant reinvention. Tilyou owned many rides, but they were scattered on unconnected parcels over a quarter mile of beachfront. When the renowned open-water swimmer Paul Boyton launched Sea Lion Park nearby in 1895—by some measures the first modern amusement park in the world—Tilyou realized that he had to consolidate his attractions into a single compound to which he could charge admission, thereby monopolizing custom while filtering out the riffraff. He also understood the value of a high-profile superattraction to draw people in—a kind of “killer app.” Boyton’s centerpiece was an exhilarating boat ride called Chute-the-Chutes; Tilyou’s was the Steeplechase Horses—the gravity horse race he adapted from an English prototype—that ran on six parallel tracks over an eleven-hundred-foot course, complete with buglers and attendants dressed in jockey silk. Steeplechase Park, named for this star attraction, opened in 1897, the first of Coney Island’s three great amusement parks. Steeplechase was larger than Sea Lion Park and soon eclipsed it in attendance. But Tilyou knew better than to rest on this success. Always on the prowl for new attractions, he met two entrepreneurs—Frederic Thompson and Elmer “Skip” Dundy—who struck gold with a ride called A Trip to the Moon at the 1901 Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo. Tilyou convinced the men to move this and two other rides to Steeplechase once the fair closed. But the following season was a disaster for Coney Island operators, with rain seventy out of ninety-two days. Attendance was sharply down throughout the amusement district. When it came time to renew their lease, Tilyou told Thompson and Dundy they would have to fork over more rent to keep A Trip to the Moon at Steeplechase. They refused. Boyton, meanwhile, was forced to close Sea Lion Park. The two men leaped at the chance to take over his grounds and strike out on their own.4

Tilyou’s greed truly backfired; for Steeplechase both lost a major attraction and gained a new competitor. In the spring of 1903, Thompson and Dundy opened their hauntingly beautiful Luna Park, a glittering jewel that made Steeplechase suddenly look frumpy and dull. In creating his park, Thompson realized that more than a mere “collection of individually ingenious rides” was needed to capture the imagination of the public. The challenge was to cast a magical master theme over the entire place, one that made the whole greater than the sum of its parts. Thompson had studied at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris and used an inventive, highly eclectic style of architecture to spin a richly theatrical setting. The result was a kind of orientalist Columbian Exposition, Chicago’s “White City” beheld through an opiate fog—an urbanism of ecstasy and delight rather than order, duty, and civic responsibility. Indeed, if the Columbian Exposition “preached discipline,” writes John Kasson in Amusing the Million, “Luna Park invited release.” Tens of thousands of electric lights transformed Luna’s staff-and-plaster buildings into a dazzling apparition at dusk. “Tall towers that had grown dim suddenly broke forth in electric outlines and gay rosettes of color,” wrote Albert Bigelow Paine in 1904, “as the living spark of light traveled hither and thither, until the place was transformed into an enchanted garden, of such a sort as Aladdin never dreamed.” A second spectacular amusement park, Dreamland, opened in May 1904, topped by a tower so tall and brightly lit it could be seen fifty miles out at sea. Tilyou knew he was in trouble.5

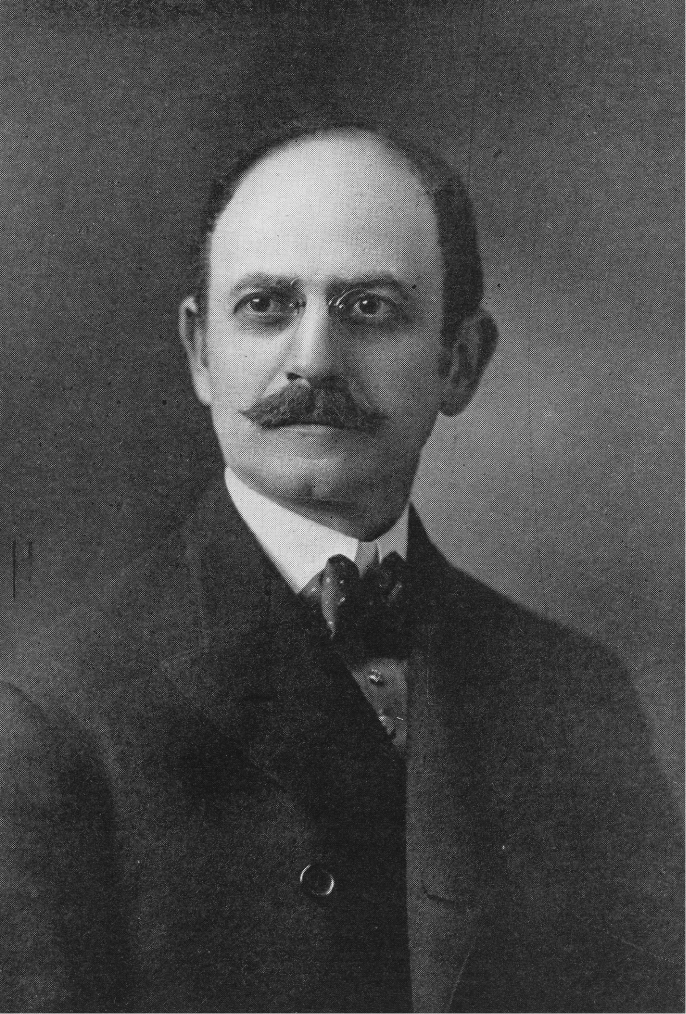

It was a desperate need to regain a competitive edge that aligned the orbits of this Brooklyn impresario with an enterprising Missouri tinkerer named Samuel Meyer Friede. Friede, born in 1861, was the youngest son of Meyer Friede, a successful German-Jewish watchmaker and silversmith with a keen interest in civic affairs. The elder Friede was the first Jew to serve in the Missouri state legislature, where he supported the Union cause and was famous for his impassioned response to an anti-Semitic screed by a fellow legislator. Meyer Friede’s older boys, Joel and Isaac, followed him into the family business. Samuel, it seems, had his eye on bigger things. Leaving school after only the eighth grade, he worked briefly as a notions and dry goods clerk, and in 1883 married an Italian woman named Christina. The couple’s only child, a daughter named Minnie, was born the next year. Marrying outside the close-knit St. Louis Jewish community evidently caused a rift with his father, who wrote Samuel out of his will (Sam filed a partition suit in response). Samuel Friede’s first passion was the machine shop. He became a serial inventor, filing in 1885 the first of many patent applications. He designed a portable fare box for streetcars, a roll-paper cutter, an automatic station indicator for passenger trains, a spring-loaded label holder for drug-store bins, a combination ratchet-and-monkey wrench, an envelope-sealing machine, and a variety of plumbing fixtures, including a “Stop and Waste Cock.” But these were mere trifles given Friede’s towering ambition. With the turn of the century, as plans took shape for a great world’s fair in St. Louis—the Louisiana Purchase Exposition of 1904—Friede saw the opportunity of a lifetime, a chance, perhaps, for this star-crossed son to prove he was a man of consequence. In March 1901 Friede unveiled plans for an iron-and-steel “Giant Aerial Globe” that would rise 555 feet above the city—equal in height to the Washington Monument. Friede promised that the colossal orb would be the fair’s biggest attraction—greater in scale and spectacle than the Ferris wheel that stole the Chicago show in 1893.6

Luna Park, c. 1905—“Electric City by the Sea.” Detroit Publishing Company Photographic Collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Friede had already been working on his globe for some eighteen months by this time, aided by Albert Borden, a prominent St. Louis engineer who built several warehouses on the industrial waterfront. As eagerly reported in the press, the orb would feature a vast aerial rotunda at the 325-foot level, enclosed in plate glass and encircled by a “movable platform twenty feet in width.” From this, the sightseer would enjoy a commanding view of the exposition grounds. At the very top would be an observatory, crowned with a pair of “gigantic searchlights, as an after-dark feature.” Borden rather wildly estimated that the structure would weight forty million pounds and cost $1.3 million to erect. Upwards of thirty thousand people could be accommodated at any given time. The globe was to rise from an elevated spot on the south side of the Forest Park fairgrounds. The remote site, far from the heart of the fair and its midway, makes little sense until seen on a map. And then it all clicks: Friede had positioned his orb on the main axis of the fairgrounds, terminating the sightline from the Plaza of St. Louis and Cass Gilbert’s Palace of Fine Arts. The great orb, in other words, would have loomed over the fair’s austere neoclassical buildings, a great Yiddish moon looming over the gathered goyim.7

Blanke’s Faust Blend Coffee to be served “In all this Colossal Structure.” Advertisement from Saturday Evening Post, October 26, 1901.

By June of 1901, Friede had convinced a prominent St. Louis businessman, Cyrus F. Blanke, to back his globe venture, forming a company capitalized with $1.5 million (more than $40 million today). Partnering with Blanke—founder of the largest coffee-roasting company in America at the time—granted immediate legitimacy to what otherwise might have been dismissed as a joke. Not coincidentally, Blanke happened to serve on both the Board of Directors of the Louisiana Purchase Exposition and its powerful Committee on Concessions—though he eventually resigned the latter post owing to conflict of interest (which the press read as a sign that the globe would win approval and might actually be built). Blanke featured the globe in advertisements, promising to serve “in all this Colossal Structure . . . Faust Blend Coffee”—an appropriate name and choice indeed, as we shall see. He even produced a promotional glass jar in the shape of the globe, a rarity that surfaces on eBay from time to time. But not everyone was pleased with the Friede-Blanke Aerial Globe, as it came to be called. To composer Emile Karst, president of the city’s Franco-American Society, the globe “seems to look dumpy, no matter what its proportions.” He feared that the great orb would “scarcely possess the surpassing artistic merits which made the Eiffel Tower world-renowned,” though he allowed that “it may be possible to remedy this inartistic defect.” Annoyed, Friede told Karst to take the matter up with Eiffel himself. Karst did just that; for as the Republic reported on June 22, Mr. Eiffel was asked “for information as to the financial and structural obstacles overcome in the construction of the Eiffel Tower.” It is not known whether the great engineer responded. Eiffel might well have been astonished to see Borden’s sketch of the globe, for it looked suspiciously like a project by one of his own students.8

Alas, the Aerial Globe was no sui generis fruit of Friede’s fertile mind but rather something he absorbed wholesale from published renderings of an 1891 project by Biscayan architect Alberto de Palacio y Elissague, who studied engineering in Paris with none other than Gustave Eiffel. Palacio went on to design scores of civic and institutional buildings in his career—including the Crystal Palace and the old Atocha train station in Madrid. He is best known for his unique Puente de Vizcaya Bridge across the Nervión River near Bilbao—the first transporter or aerial transfer bridge in the world, today a UNESCO World Heritage site (a roadbed gondola, slung beneath the structure and loaded with vehicles, is pulled across the span). In 1891 Palacio unveiled plans for a heroic monument to Christopher Columbus in the form of a mammoth globe, 1,000 feet in diameter and rising 1,400 feet from a great iron pedestal that—at 262 feet—was itself no mean structure. Palacio meant the orb for a planned Spanish exhibition marking the four hundredth anniversary of the Columbus voyage—what became instead the rather modest 1892 Exposición Histórico-Americana in Madrid. An early rendering shows the monument hovering over Palacio’s Crystal Palace in Buen Retiro Park, site of the Exposición. When it became clear that Spain lacked the resources to erect his colossus, Palacio submitted his drawings to a competition sponsored by the 1893 Chicago World’s Columbian Exposition. He walked away with first prize.

Of course, the orb was not built in Chicago either. But Palacio’s Eiffelian pedigree and the sheer audacity of his Columbus monument—reminiscent of Boullée’s 1784 cenotaph for Isaac Newton—assured it great publicity. An ethereal rendering of the Chicago globe first appeared on the cover of Scientific American on October 25, 1890, and was widely reprinted over the next two years—in the Spanish periodical La Ilustración Española y Americana, the British Printer, the New York–based Manufacturer and Builder, and a popular English pictorial called the Picture Magazine. In the view, the soaring sphere is cottoned by clouds and hovers over a riverine city—presumably Chicago. Belting the equator is a great balcony, nearly half a mile long and studded with hundreds of cabanas. Its most delightful feature is a spiral cog tramway that winds upward to the polar cap, topped by a meteorological observatory in the form of the Santa Maria—“the caravel,” the Manufacturer and Builder reminded readers, “which carried Columbus to the New World.” A corresponding track ran inside the southern hemisphere, taking visitors up to the equator from the great Roman-arched base—where an auditorium, museums, and a “large Columbian library” would be located. The interior of the sphere was to be decorated with the constellations; the oceans and land masses on the exterior traced by lights and “casting over the city torrents of refulgent brilliancy.” All in all, this would be “one of the wonders of the world.”9

Cover of October 1890 issue of Scientific American with a rendering of Alberto de Palacio’s “Colossal Monument in Memory of Christopher Columbus.”

Sam Friede’s globe, first published in the St. Louis Sunday Republic on March 17, 1901, is a shameless duplicate of Palacio’s Columbus monument—from the observatory right down the spiral tramway to its Roman-arched steel-frame base. It seems incredible that the St. Louis press, in all their coverage of the Aerial Globe, never figured out that Friede had brazenly pilfered his idea from overseas. Or they may have been well aware of the orb’s Latin provenance but chose to keep the matter quiet. What would it profit St. Louis, after all, to point out that local-boy Friede’s mighty orb—a Midwestern landmark in the making, an Eiffel tower of the prairie!—was in fact a Spanish import cast aside by that mighty nemesis to the north, Chicago? But Friede was a quick study, and soon his globe bore only passing resemblance to the Palacio scheme. What next appeared in the St. Louis press is a far less literal representation of the earth, an orbital edifice that revealed “the extreme possibilities of steel structural work” and might have actually been buildable. The new globe was also more circumscribed in its cultural pretensions. Stripped of museums and library, the Friede-Blanke Aerial Globe would be instead “a collection of amusements in midair, containing provision for every form of popular diversion from grand opera to vaudeville . . . from pipe organ concerts to a three-ring circus.”10

But none of this was to be. For reasons obscure, Cyrus Blanke ended his partnership with Friede in the fall of 1901. He is conspicuously absent from a half-page advertisement that ran in the Republic in November—promising “A City in the Clouds,” with gardens, a coliseum, and music by a “gigantic orchestrion.” Listed instead as vice president and treasurer is Frank A. Ruf of the Antikamnia Chemical Company, a maker of habit-forming patent medicines. The next month, in a front-page Republic piece just before Christmas, again nary a word is mentioned of Blanke. Did Blanke begin to doubt the legitimacy of Friede’s venture, or the sketchy method he devised to finance it—by public subscription, raising capital by selling stocks to the public for a dollar a share? Whatever the reason, Blanke vanishes and—not long afterward—so, too, does the tower itself. After January 1902 the project never appears again in the local press. Friede’s St. Louis globe thus had another thing in common with Palacio’s orb—neither project ever saw the light of day. Unfazed, Friede was soon back in his shop. He set his sights a bit lower—for a time at least. Inspired by a 1903 competition for an “air yacht,” Friede submitted a patent application for an amusement park ride named the Revolving Airship Tower. The contraption featured a rotating tower, sixty-five feet square at the base, that flung four suspended cigar-shaped “airships” outward by centrifugal force. The cars were lifted up the tower by cable and fitted with mirrors, “so that, no matter which way the passenger looks, he sees nothing but a birdseye view of the country.” Friede formed a company in Chicago to build the tower and erected a prototype the following year at Chicago’s popular Sans Souci Amusement Park, whose general manager—Miles E. Fried—may have been a relative. It was certainly no Aerial Globe; but at least it was real. More importantly, it caught the eye of George C. Tilyou.11

It is not known exactly when or how Tilyou and Friede first met—Friede may have sent Tilyou material about his Airship Tower, or, more likely, the two might have crossed paths at the Louisiana Purchase Exposition. But however it happened, they hit it off immediately. For all their differences, the Brooklyn Irishman and the Missouri Jew were equally ambitious and shared a common passion for entertainment. Friede was soon in Brooklyn himself and by November 1904 had incorporated the Revolving Airship Tower Company of New York to erect a second, taller airship tower at Steeplechase Park. He also developed a second ride for Tilyou, the figurative opposite of the Airship Tower—a theatrical piece called Atlantis Under the Sea. Both attractions were in place for the 1905 season and were a great hit with the public. As Edward S. Sears put it in his Souvenir Guide to Coney Island, the Airship Tower and Atlantis Under the Sea were “the most striking novelties at Steeplechase . . . the sensations of the season.” Sears was especially impressed with the airship ride, which he called the “piece de resistance, so to speak, of Steeplechase Park.” The tower was three hundred feet tall—or so Tilyou and Friede claimed—and “with its 15,000 electric lights of alternating crimson and white serves as a fitting landmark for this great pleasure garden.” Thus, wrote Sears, despite being “eclipsed and shadowed . . . by the magnificence of its younger rivals,” the new rides made Steeplechase shine forth “with a radiance fairly equaling Luna Park and Dreamland.” Tilyou was back, and thanks largely to Samuel Meyer Friede.12

Samuel M. Friede, illustration for an “Amusement Apparatus,” 1906. United States Patent Office.

Samuel M. Friede, illustration for a “Revolving Air Ship Tower,” 1906. United States Patent Office.

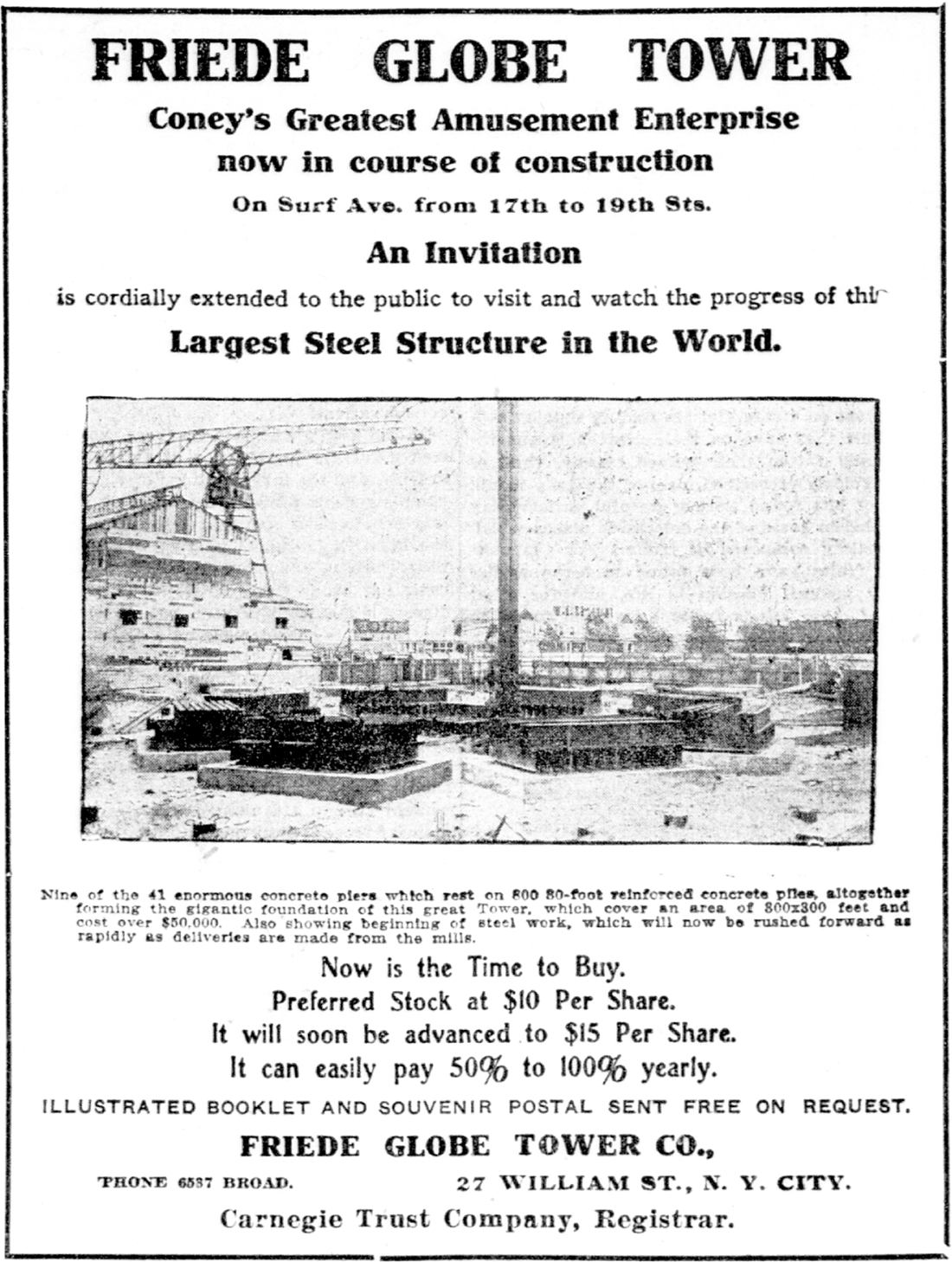

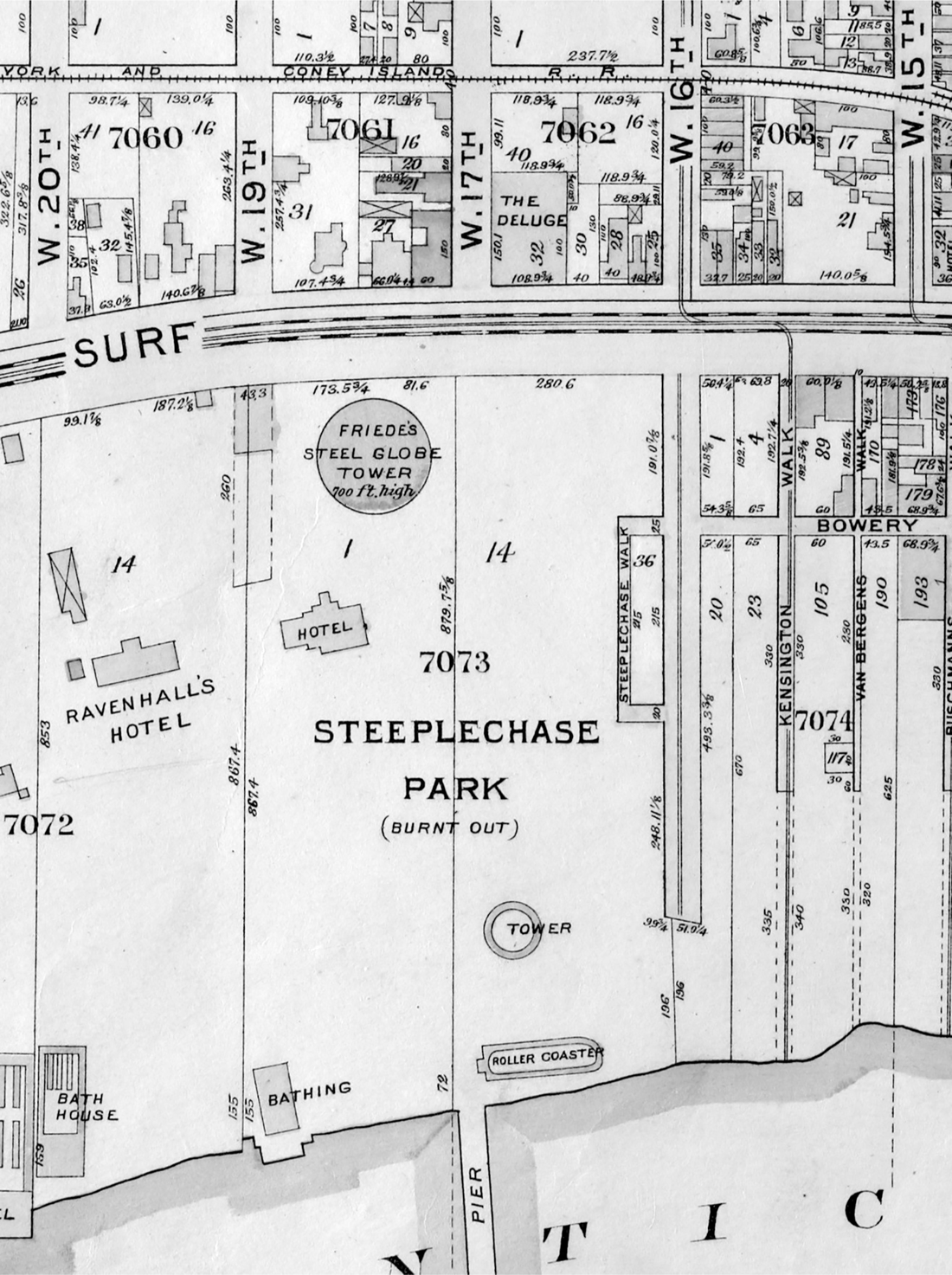

This success convinced the Missourian that his mighty mothballed orb might take more readily to the sands of seaside Brooklyn than it did to prairie loam. He soon convinced the Steeplechase showman that his globe tower was the “killer app” that would bury Dreamland and Luna Park once and for all. On October 1, 1905, Tilyou offered Friede a twenty-five-year lease for a two-acre parcel within Steeplechase Park, on Surf Avenue between West Seventeenth and West Nineteenth streets. Rent would be $25,000 a year, due quarterly. That January, Friede announced the formation of the Friede Globe Tower Company. With offices at Steeplechase and 27 William Street in Manhattan, the concern was nonetheless registered—nefariously, as will soon become clear—in the state of Arizona. Friede flooded city newspapers with advertisements and published a plush “Red Book” prospectus that was available on request (along with a free six-month subscription to Industrial Amusement Record, a perk of rather dubious appeal). A broadside in a January 1906 Sunday edition of the Sun offered to the public $250,000 of preferred stock at $10 a share. As an incentive, he would toss in a free share of common stock for every one of preferred stock purchased. A week later, Friede reported that “we have been working night and day making out stock certificates and indorsing [sic] checks, and over $50,000 of the stock is already sold and subscribed for to date.” Promising stock performance of “100 per cent interest annually,” Friede cleverly pitched his capitalization scheme as democracy itself: “We prefer to have 100,000 stockholders with $10.00 each than one stockholder with One Million Dollars”—for the raising of this great building, he claimed, was “an enterprise to be owned by the people, for the people.” (This would also, a cynic might point out, spread deception so widely as to make a coordinated legal challenge unlikely.) To reward its common builders, Friede promised an exalted “Hall of Names” in the globe itself. “This marvelous room,” he avowed, “will contain the names of every man, woman and child purchasing one or more shares of stock . . . inscribed in alphabetical order on metal plates, to remain for all time to come.”13

Certificate of four shares of common stock in the name of Louise B. Carsledge, Friede Globe Tower Company, 1906. At $10 a share, Carsledge had invested the 2018 equivalent of about $1,100 in Friede’s scheme. Courtesy of David M. Beach, cigarboxlabels. com.

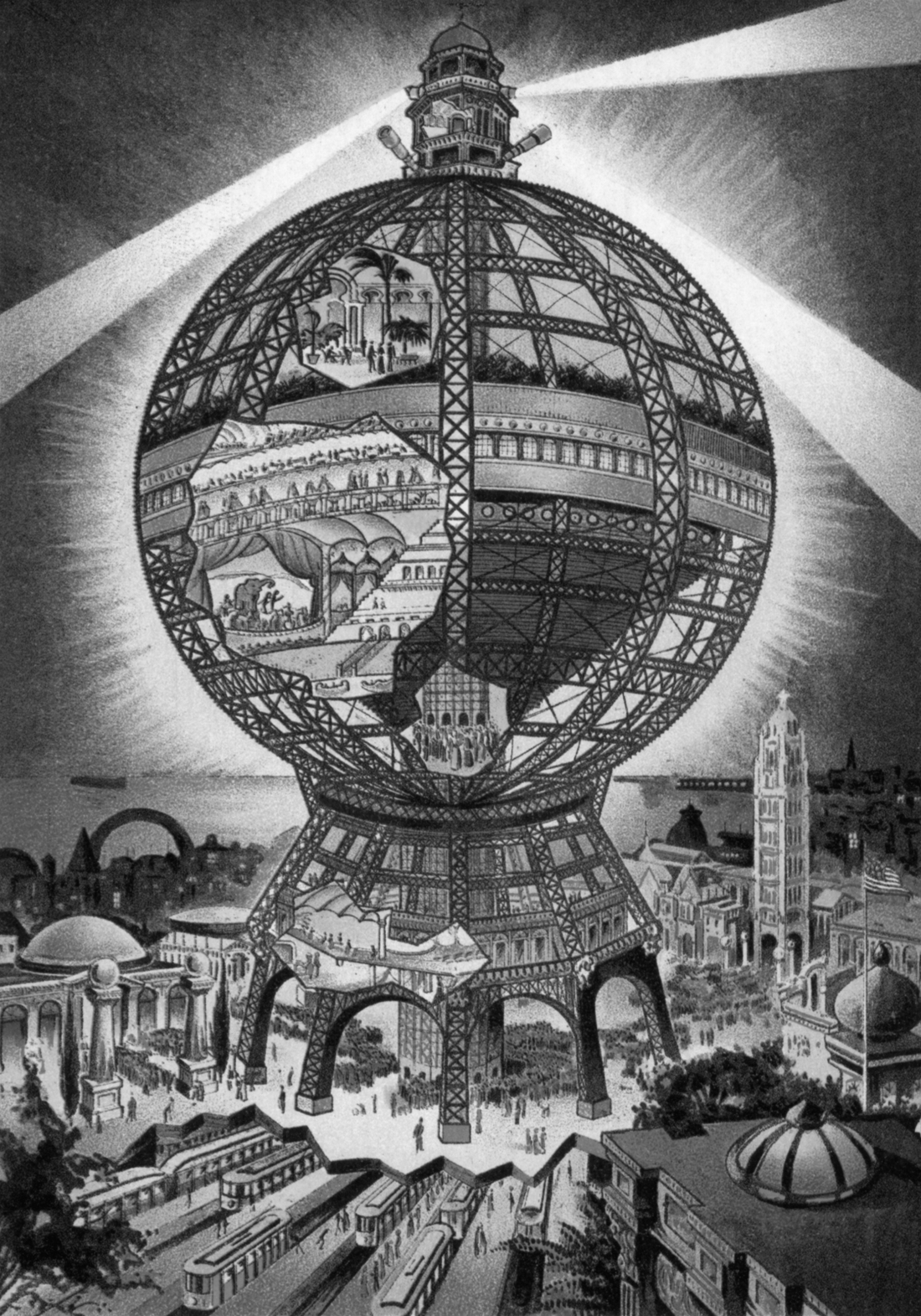

And what, beyond a polished nameplate, would the people’s hard-earned pennies buy? All the wonders of the world, it would seem. As Friede’s “Red Book” gushed, the new Globe Tower—designed with the prominent New York firm of Cleverdon & Putzel, architects of the Astor Building—was to be quite simply “the most gigantic, unique and permanent amusement structure in the world . . . the greatest building in existence” and “more to America than the Eiffel Tower is to France.” From its base just off Surf Avenue (at about where the entrance stairs to MCU Field are today), the titanic gourd would swell to nine hundred feet in girth and loom seven hundred feet above the sand and racket of Coney Island. Some eight thousand tons of steel would go into the globe—“more steel than was used for the construction of the Williamsburg Bridge.” The Flatiron and Singer buildings, the Metropolitan Life Tower, would all be “mere pygmies, architecturally speaking, in comparison.” A constellation of electric lights would make it “a gigantic tower of fire by night.” Inside, visitors would discover a “Department Store of Amusements” filling the orb’s 500,000 square feet of floor space—the equivalent of six city blocks. Those arriving by automobile would park beneath the great pedestal base, under which—according to some illustrations—would be a subway station (never mind that ocean water would immediately fill anything more than a few feet below the sand). Riding one of the ten huge elevators (“largest ever built”), visitors would pass an “Aerial Hippodrome” with slot machines and a “Continuous four-ring Circus”; an immense ballroom belted by a mechanical café that crawled the belly of the tower was “equipped with comfortable chairs and tables where a table d’hôte meal is served.” Above this would be an “Aerial Palm Garden,” with pools, cascades, and statuary and—soaring overhead—“beautifully curved steel arches, 150 feet high” that rose to the Observatory, five hundred feet above the street. From the catwalk promenade there, it would be impossible to see anything of the structure beneath, a sensation “most novel and exhilarating,” testified the prospectus, and “suggestive of being suspended, or floating, as it were, in mid-air.” At last came the vaunted “Hall of Names” and, above that, a US weather observatory and wireless telegraph station topped by a great flagpole and the world’s largest, brightest revolving searchlight. All told, fifty thousand people could fill the mighty colossus at any one time.14

Friede called on the public to witness the launch of the Globe Tower on May 30, 1906, promising that “everything possible will be done by the company to make the cornerstone laying a notable event.” A crowd of several thousand spectators gathered to hear speeches by Friede and a number of company officers, and hear “celebrated orators” including a retired third-tier judge, E. Y. Bell of New Jersey, who “spoke of the Friede Tower as the eighth wonder of the age and compared it with the Collossus [sic] of Rhodes.” At five o’clock sharp, a former assemblyman laid the cornerstone on behalf of Brooklyn borough president Bird S. Coler, accompanied by fireworks and music performed by the uniformed Friede Tower Band (led by an Italian of minor fame named Filipo Govarale, of whom we shall hear more in a moment). The cornerstone was evidently equipped with a chamber that held “a facsimile of the company’s charter, a menu of the dinner given to the newspapermen . . . and a set of coins.” Afterward, Friede led a large group of his stockholders to Stauch’s Casino for a banquet. The guests were likely not informed that their host didn’t even have a building permit for the great globe they had just christened. It was not until August 8, 1906—more than two months after groundbreaking—that the Globe Tower finally received the critical permit—“the largest ever issued of its kind,” as Friede predictably spun it. A month later he awarded a construction contract to the Alfred E. Norton Company of New York. On Sunday, February 17, 1907, investors saw the first tangible evidence of Friede’s promise to build. That afternoon some two thousand New Yorkers—a huge crowd for Coney Island in winter—braved a fierce wind to witness the “setting above ground of the first steel” for the mammoth Globe Tower (“the cold weather,” noted the Brooklyn Eagle, “did not seem to prevent many women from attending”). Conductor Govarale led the Tower Band, and then “President Friede” addressed the crowd, telling of the work already done—that “600 of the 800 concrete piles needed for the foundation have already been sunk.” Each was driven thirty feet deep, and together they would create a bed for the forty-one concrete piers that formed the socles, or pedestals, from which the great steel structure would rise.15

But even as the globe began to take shape, Friede’s relationship with Tilyou faltered. The project was already far behind schedule—construction was supposed to start in October 1906. Work had been delayed nearly a year, allegedly because of Tilyou’s refusal to remove several small buildings that Friede claimed were on his leased parcel. Now, emboldened by the groundbreaking and with many tons of steel stockpiled on-site, Friede directed his workers to raze the Steeplechase structures on the disputed boundary. Tilyou responded swiftly. As the New York Times reported, once the “tower people” started to tear down the buildings, a Tilyou lieutenant rushed out to stop them, backed by a dozen Steeplechase men—“a force of carpenters, bricklayers, and plumbers.” The Coney Island police were called; Friede’s construction superintendent was arrested, not once but twice. Tilyou was a powerful man in Coney Island; by virtue of ethnicity alone he could count on the Coney Island reserves as a private security force (Brooklyn’s police ranks were nearly all Irish then). Not so the supreme court of Brooklyn, which came down on Friede’s side, granting him an injunction to prevent “any further interference on the part of the Steeplechase people.” Tilyou had met his match. Indeed, it would later be revealed that Friede had a secret weapon in Borough Hall that made even the mighty George C. Tilyou quake—an ally with power enough to shut down every ride in Steeplechase Park. Tilyou’s hand thus stayed, Friede retracted his threat to “shut off the park’s view of Surf Avenue” by erecting a tall fence around his site. Friede was rolling now. He placed another big order for Pittsburgh steel on March 31—four thousand tons’ worth—enough, reported the Times, to “bring the tower up to a height of 350 feet.” Friede paid cash in advance, and arranged for a second load of steel—another four thousand tons—to be sent once the first order was received. Work on the concrete foundations was fast nearing completion; things appeared to be quite literally looking up. By now, some two thousand men and women had purchased shares of Friede Globe Tower Company stock. With such concrete proof now on the ground, hundreds more contributors rushed forward with cash in hand. And then it all began to unravel.16

“The Steel Globe Tower, 700 Feet High.” Lithograph postcard, Samuel Langsdorf and Company, 1906. Collection of the author.

When the best-laid schemes of men and mice go awry, it’s usually due to misplaced trust. Unbeknownst to Friede, the man he put in charge of all Globe Tower financial matters, Henry Clay Russell Wade, had a very dodgy past. A Canadian dry goods clerk who came to the United States in the 1880s, Wade had been charged with petty theft and “passing queer checks”; later convicted of “running a bucket shop on lower Broadway,” he was sentenced to three months in jail. As president of a shady outfit known as Empire Bond and Securities, Wade had conned a Canadian landowner into floating a timber company with bonds backed by his very own Imperial Trustee Company—“a fictitious concern,” reported the New York Sun, “connected with the bogus ‘Hanover Bank of Boston.’” Wade was arrested again, this time for grand larceny, in June 1905, only months before Friede launched his Brooklyn venture. The Missourian blundered into a contract with Empire Bond and Securities to sell Globe Tower stock, making Wade company treasurer in the process. He even encouraged Wade to rent an adjacent office at 27 William Street. Thus Friede not only let the fox into the henhouse; he gave it a knife and fork. Soon enough, Wade began embezzling funds. Friede found out, and in early August 1906 he fired Wade and reported him to the district attorney’s office. Indicted, Wade promptly disappeared, only to return the following spring to stun Friede with a countersuit—claiming he was owed $36,000 in unpaid commissions. Incredibly, because the Globe Tower Company was registered in Arizona and thus considered a “foreign corporation,” Wade was able to take legal action against it despite being a fugitive himself. On April 8, 1907, sheriff’s deputies marched into Friede’s William Street office to attach the furniture. The company’s bank account was frozen, while officers swept down on Steeplechase to seize Friede’s stockpiled lumber and steel.17

Portait of Samuel M. Friede in his Red Book prospectus for the globular “Department Store of Amusements,” 1906. The Huntington Library, Rare Books Department.

Friede posted bond easily enough, and the attachments were lifted the next day—“SHERIFF RELEASES EIFFEL OF CONEY,” shouted the New York Herald. But the Missourian was outraged. He attacked the district attorney’s office for failing to arrest Wade, and as soon as the sheriff’s deputy left his office, Friede “put up notices over the place,” the Herald reported, “calling Wade by various impolite titles. He pasted epithets above him on the blue prints of the plans of the tower,” and called police headquarters demanding to know why Wade—rumored now to be hiding out in Philadelphia—had not been arrested. Friede offered a reward for his capture, and within days Wade was hauled into custody by Pinkerton men and handed over to the police. The arrest made the front page of the New York Times. This time Friede accused Wade of having absconded with $15,000—several times the previous sum. Tilyou chimed in, too, charging that Wade had pocketed a check he was meant to deposit. It took real moxie to cheat world-wise men like Tilyou or Friede. The Brooklyn Eagle offered a portrait—describing Wade as a “well built, well dressed young man,” with “keen, steel blue eyes. His manner is suave, his tongue glib, and those who have had dealings with him say that he is one of the shrewdest promoters it was ever their fortune—or misfortune—to meet.” Wade pleaded not guilty, but was convicted of embezzlement and sent to Sing Sing for a lengthy prison term. But he would have his revenge, as we shall see.18

The thieving Canadian was hardly the only scoundrel Samuel Friede had on board. A few weeks before the Wade affair exploded, the Brooklyn Eagle revealed that a prominent city official, Edward A. Langan, had been appointed vice president of the Friede Globe Tower Company. Langan was chief inspector of elevators for the Brooklyn Bureau of Buildings. Without elevators, the Globe Tower was just a giant steel-framed gourd. Elevators circa 1906 were still a primitive technology, an Achilles heel of the building industry; those in the tower would be the largest and most mechanically complex ever built. It mightily behooved Friede to befriend this man responsible for approving elevators in Brooklyn. But Langan was no pushover; it would take more than a title to “fix” this corrupt and seasoned operator. Soon enough, inspector Langan was making a tidy commission selling shares of Globe Tower Company stock. When pressed by a reporter about this astonishing convergence of duties in a single man, Friede was matter-of-fact, describing Langan as “an energetic, hustling underwriter”—a man “deeply concerned with getting others to invest their funds in the company’s securities.” Friede further explained—needlessly—that Langan was “an invaluable man to us,” who “from his official position . . . knows how to cut a lot of red tape and get straight to the goal, without loss of time, when it comes to our obtaining permits.” Moreover, he proved to be an especially effective salesman, “turning in subscriptions by the cartload almost every day.” When the reporter asked how “a friend” might go about purchasing Globe Tower stock, Friede replied, “Send him right over to Mr. Langan . . . at the Borough Hall.”19

Advertisement for Friede Globe Tower stock with photograph of socle piers under construction. From New-York Tribune, June 9, 1907.

For a brief time, work on the tower continued despite the gathering scandal. In early summer 1907 Friede ran an advertisement in the New-York Tribune that included one of only three known photographs of the Globe Tower structure. In the foreground are nine massive concrete piers, each built over a cluster of concrete piles driven beneath the sand. The nine piers form the foundation for just one of the great socles upon which the mammoth steel-frame pedestal would rest. In the advertisement, Friede explained that there were to be forty-one such piers in all, built atop a grid of eight hundred piles. The foundation photograph appeared in the June 9 issue of the Tribune. Eight weeks later disaster struck. In the early morning hours of July 28, a fire broke out in Tilyou’s Cave of the Winds. It spread rapidly, burning out of control the whole day and well into evening. By the time it was quelled, Steeplechase Park was a smoldering ruin. The irrepressible Tilyou was quick to market the disaster—famously charging admission to the still-burning wreckage and promising to build a bigger and better Steeplechase atop the ruins. The fire put a decisive end to the poisonous relationship between Tilyou and Friede. In an “Open Letter” in the New-York Daily Tribune that fall, Friede bewailed “the many obstacles which have . . . caused considerable delay in the construction of our Gigantic Enterprise,” and he sued Tilyou for $245,000 in damages. The men also quarreled over the charred remains of the Revolving Airship Tower, totaled by the fire. In his rush to rebuild, Tilyou had unceremoniously sold off the wreckage to a salvage firm. Furious, Friede sued. Tilyou was served an injunction, but the charges were later dismissed.20

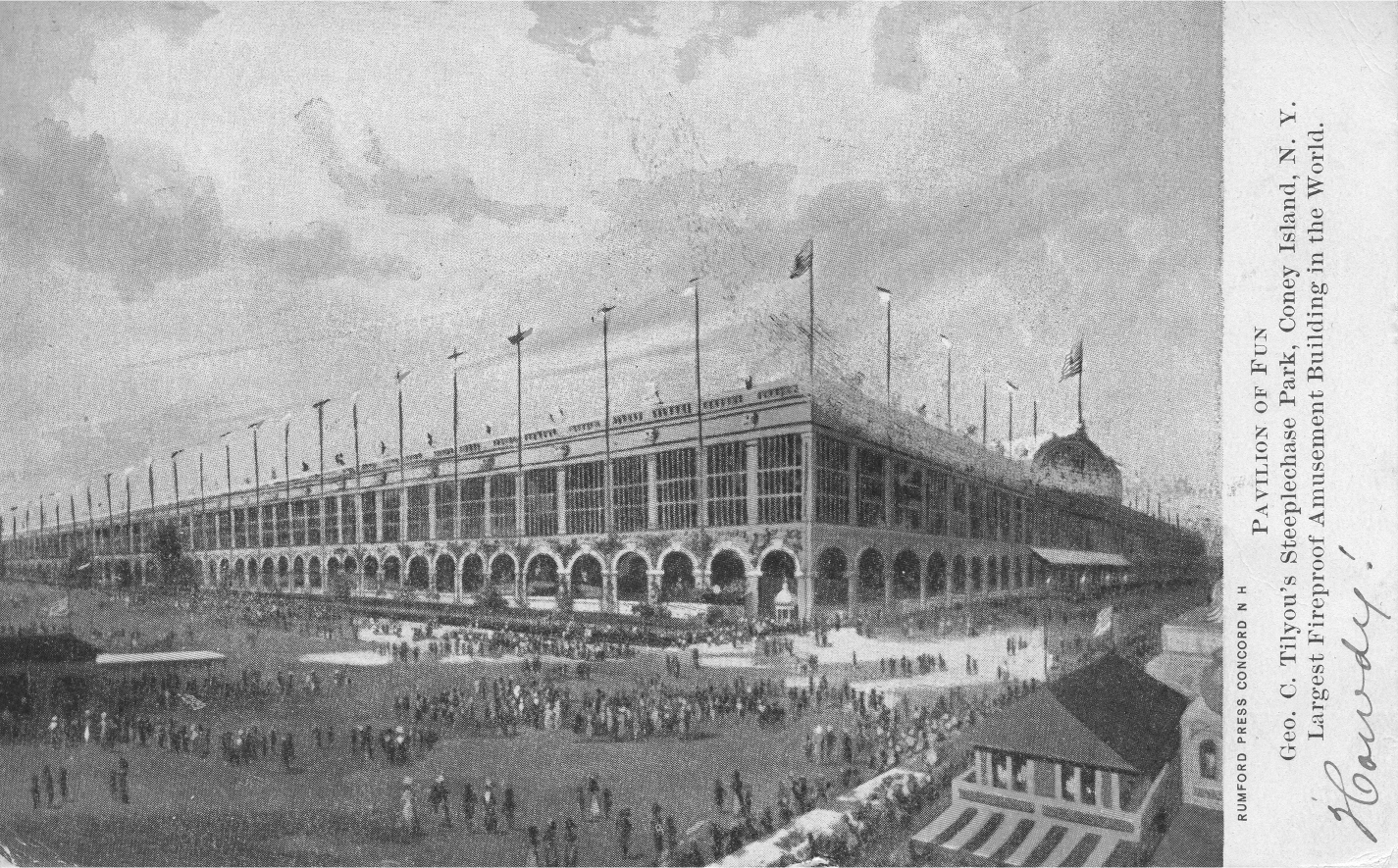

With Langan exposed and demand for Globe Tower stock incinerated by the fire, Friede was having serious financial problems—or so he claimed. In January 1908, after two years of punctual payments, Friede failed to make the quarterly rent. Tilyou hauled him into court, and this time the Globe Tower Company was evicted from Steeplechase. By now, Tilyou was working around the clock to get his mammoth 120,000-square-foot Pavilion of Fun finished for the 1908 season; the last thing he wanted on opening day was charred relics of failure. The Globe Tower signs were pulled down easily enough; but the great concrete piers were a lot more difficult to get rid of. They would sit abandoned for more than a year, gathering birdlime and soot. Finally, in February 1909, Tilyou commissioned H. J. Linder and Company to have Friede’s foundation literally blasted out of the ground. “EVICTION BY DYNAMITE,” the Eagle shouted. The steampunk orb, barely yet born, was now no more. And vanished too, it seems, was its erstwhile maker; for Samuel Friede had taken leave of both Brooklyn and America by the time Tilyou blew away the remains of his steampunk orb. The Missourian had never been out of the country before; now he hastily applied for a passport (occupation: “architect”) and by the fall of 1908 was off to Europe with his wife and daughter.21

Friede was fleeing not only the tower scandal but a second fiasco in its wake. In an attempt to shelter the fugitive stock of the Globe Tower Company, he launched yet another venture—the Coney Island Hippodrome Circus, a swindle built atop a scam (or, as the Eagle put it, “the dying gasp of the Friede Globe Tower Company”). The centerpiece this time was a mammoth tent, largest in the world, erected about the steel supports of the aborted orb. Enclosing an area of 77,400 square feet—nearly two acres—it had seats on all sides “in true circus fashion,” and could accommodate an audience of sixty-five hundred, more than Madison Square Garden at the time. The big top was set aglow at night by 250 arc lamps and fifteen thousand lightbulbs. Under it were three rings and two stages, upon which “for three solid hours,” anticipated the New-York Tribune, “there will not be a minute in which something is not happening.” Friede announced that the first hundred unmarried couples at the gate—“sweethearts who are engaged or hope to be”—would be admitted free on its Memorial Day opening, May 30, 1908. On the bill were acts from the American West and England, France, Italy, Russia, and Turkey—the famous Nelson family of aerialists from London, a “death-defying automobile act” by the Devillos, Captain French’s Wild West Rough Riders (with “genuine Sioux Indians”). Among the animal acts were Professor Bristol’s Troupe of Performing Ponies, John G. Robinson’s elephant show from Ohio, and a lion act with Captain Jack Bonavita, a dashing trainer who had lost an arm to a Coney Island cat four years earlier but found subsequent fame commanding—single-handedly—a troupe of twenty-seven lions. Billed as America’s first “permanent circus,” the Hippodrome lasted all of two days. Expecting to be paid, the two hundred-odd circus employees were treated instead to dinner at a nearby hotel. “When the acrobats and performers returned to the circus lot,” reported the Tribune, “everything had been sold, and it was explained that the show had been discontinued.” In fact, nearly all the equipment—including the great tent, horses, stage props, dozens of wagon cars—was owned by Friede’s major partner in the venture—the Bode Wagon Works of Cincinnati, renowned makers of the ornate wagons used by the Ringling Brothers and other circus companies. When the ill-fated circus defaulted on a required payment—on opening day, no less—Albert Bode moved fast to take possession of his property. Much of it had already been carted off to Jersey City, “out of the jurisdiction of the Kings County Sheriff.” The slippery Friede had himself exited the picture, having “sold his interest when it became known that the project would fail.”22

Detail from plate 29 of G. W. Bromley and Company, Atlas of the Borough of Brooklyn (1907), showing Friede Globe Tower site amidst burned ruins of Steeplechase Park. Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division, The New York Public Library.

With his family in tow and ill-gotten gain in his pockets (a yearlong sojourn in Europe could not have come cheaply), Friede stayed well away from New York until September 1909. He was thus conveniently out of reach when the nine-lived Henry Wade was released from Sing Sing, singing a tune himself. In late summer 1909 Wade made a series of revelations that kept the city desk hopping despite the August heat. Friede, it turned out, had first run into Langan when he was building the Revolving Airship Tower, and had to “fix” the good inspector with twenty-five thousand shares of stock and $3,000 in cash to get the plans for the Globe Tower through the Brooklyn Bureau of Buildings. Langan was, moreover, the secret weapon Friede used to keep Tilyou in line. Among his responsibilities was assuring the safety of rides at Coney Island. Whenever Friede had trouble with Tilyou, he would call Langan to send an inspector down to Steeplechase; and invariably a grave violation would result. A shuttered ride on a summer weekend was very costly, and not even Tilyou’s beloved horse coaster—namesake of Steeplechase—was safe from the Bureau of Buildings’ newfound passion for public safety. And just as Tilyou suspected, it was Langan who had had the disputed Steeplechase shacks torn down. “They came to me, the Friede people,” Langan recounted under oath; “I advised them to go ahead and tear down the buildings.” When Tilyou complained to borough president Coler, matters got even worse. Inspectors swept down on Tilyou like avenging angels, subjecting him to a “systematic pounding” and placing violations “on almost every amusement device in Steeplechase Park with the possible exception of the ocean.”23

The truth also came out about Langan’s uncanny knack for selling Globe Tower stock. He simply forced applicants for building bureau permits or approvals to buy a cartload of Globe Tower stock before he would sign off on anything. “These people,” Langan smugly said of his victims, “cannot refuse to buy.” According to Wade, the inspector spent at least twenty-five hours a week for six months in his Borough Hall office serving not the people of Brooklyn, but the Globe Tower Company, selling its dubious stock on a 15 percent commission. Langan had also assigned several Bureau of Highways engineers to survey the tower site and stake out the foundation, using the city’s rod, transit, and other equipment. Just as damning was Wade’s allegation that, as it began to look less and less likely that the globe would ever be built, Friede and three of his officers—including Langan and engineer William J. Burdette—conspired to divide up the cash from sales of Globe Tower Company stock. All told they harvested $345,000, of which $146,000 was paid in sales commissions and engineering expenses; thus some $200,000 was divvied up among the four—making them all rich overnight. And that mighty bank of elevators, largest in the world, the very mechanism by which this titanic “Department Store of Amusements” would function? They hadn’t even been designed yet at the time Langan’s office approved them. “There were no plans for elevators,” engineer Burdette admitted; “If there were, I would have drawn them.” Langan’s powerful, thoroughly crooked Bureau of Buildings turned out to be the tail that wagged the administration dog. If Friede expressed concern about Coler, Langan would respond, “Leave it to me . . . What I say with Coler goes.” The Globe Tower investigation became a central part of a lengthy and often sensational probe into the hopelessly corrupt Coler administration, led by a tenacious young Tammany-slayer named John Purroy Mitchel, then New York City commissioner of accounts, who would later become New York City’s youngest mayor.24

Brownie camera photograph of the Globe Tower socles under construction, 1907. Courtesy of Paul Brigandi.

In all, some two thousand investors—large and small, rich and poor, even schoolchildren—bought shares of Globe Tower stock. “Professional men were just as gullible as the day laborers,” wrote the Eagle; and it was “as easy to get business men who should have known better to bite at the tempting bait as it was to rope in those who were richer in artistic temperament than in common sense.” Some Langan had forced to pony up in exchange for building permits; others—like William Stead, a former manufacturer—were lured by promises of titles and other rewards. Stead was made a director in exchange for dropping a cool $10,000 on the venture ($250,000 today). Edwin J. Quinn, Friede’s superintendent of construction, called them all “suckers” but was good enough to include himself in that number. Some of those fleeced by Friede and company lost their life savings to the scam; none would ever get a penny back. One such victim was Maestro Govarale of the Globe Tower Band. Govarale enjoyed modest fame as a conductor at the time—the Brooklyn Eagle described him as “the famous Italian director.” Seduced by Friede’s offer to make him a company officer and musical director of the entire enterprise, Govarale invested $5,000 in the tower scheme. But he grew suspicious when Friede would “come around with his wife in automobiles and diamonds,” while at every board meeting he would be asked to invest more and more money. He was soon convinced that the tower was a scam and had been from the start. “In my opinion that company was organized to rob people.” On the witness stand, he cried that Friede and his henchmen “took my money all . . . all I had saved in twelve years.” Govarale was ruined and wished to see Friede “hanging.” “Poor Fillipo’s dreams were shattered,” the Eagle lamented; “He is now eking out a commonplace existence by playing music in an uptown restaurant in Manhattan.”25

Was Samuel Friede’s venture a swindle from the start, or did the Missouri tinkerer truly mean to build his titanic orb? It’s a question that will likely never be answered. There was probably more than a little good intention at the outset, but it was corrupted by the lure of a quick and easy fortune. Or perhaps Wade and Langan bullied Friede into turning his tower dream into a scam. It’s impossible to know when the Rubicon was crossed—perhaps as it became increasingly clear that stock sales would never cover the full cost of erecting the colossus, or that even its very construction might be impossible. In any case, breaking ground for the massive footers and stockpiling tons of steel on-site for all to see—even “fixing” officials like Langan to secure a valid building permit—all became part of an elaborate, very effective ploy to convince skeptics that the project was real. Indeed, “the most active stock-selling period,” recounted the Eagle, “was while the foundations were being laid, and for some time afterward”; for now even the cautious and skeptical “began to take an interest when they saw the foundations actually going down.” George Tilyou had begun openly questioning Friede’s good faith in the summer of 1906, when borough president Coler arrived one morning with a crew of workers. They were to inspect the foundation to make sure it complied with the plans filed with the Bureau of Buildings. Those called for pilings to extend at least thirty feet below grade; tests that day revealed they were sunk no more than eighteen feet. The short pilings only fortified Tilyou’s conviction that Friede never intended to erect the tower—a charge that was vociferously denied. Tilyou then presented Friede a little challenge: if he would “guarantee the completion of the tower and would get some reliable surety company to go on their bond . . . he would cancel the lease for $25,000 a year and give them a new lease for only $1 a year.” In other words, Tilyou offered Friede a fourteen-year lease on a priceless patch of Coney Island for all of $14. No one took him up on the offer.26

But even with its mortal remains blown out of the ground, the ill-fated orb lived on in spirit. Years later, a letter to the Eagle—“An Iridescent Dream”—lamented the collapse of Friede’s “grand enterprise.” “I was anticipating its completion with much pleasure,” related the correspondent, presumably unstung by the stock swindle, to “enjoy the sensation of being seated on one of its moving platforms, eating a good dinner, smoking a good cigar . . . while being carried slowly around the horizontal equator of this great steel globe.” Why not try it again? “It seems to me that it ought to be a good and safe investment,” offered this amnesiac, “to build a tremendous steel and concrete building right out in the ocean . . . where they would not have to buy the site or pay rent.” But the most enduring legacy of the Globe Tower was Steeplechase Park, version 2.0. George C. Tilyou might have rued the day he ever met Samuel Friede, but he owed the Missourian a debt of gratitude for planting in his head an idea that would make Steeplechase the foremost amusement park in the world. Instead of simply rebuilding his complex after the 1907 fire, Tilyou hired architect Reynold H. Hinsdale to design a monumental steel-and-glass “Pavilion of Fun” in which to house all his rides. The structure, 450 feet long and covering nearly three acres, gave him an immediate competitive advantage over all Coney operators simply by allowing him to open in inclement weather.27

Architecturally, the pavilion belonged to another age. Artist Reginald Marsh, who sketched and painted scenes at Steeplechase Park all through the 1930s, regarded it as the “last and greatest example of Victorian architecture in the United States.”28 Similar shed-like structures, framed with cast iron and sheathed in glass, had been erected as early as the 1820s. The Crystal Palace, built for the Great Exhibition of 1851, was the wonder of Victorian London. Victor Baltard’s vast Halles de Paris, part of Haussmann’s modernization campaign and the setting for Emile Zola’s Le Ventre de Paris—was the largest market complex of nineteenth-century Europe. It was dwarfed a generation later by the Galerie des machines at the 1889 Exposition Universelle in Paris, the largest vaulted building ever constructed. In the United States, such structures were built in New York in 1853, in Philadelphia for the 1876 Centennial Exposition, and in Jersey City a decade later—the vast terminal shed of the Central Railroad of New Jersey, today a ruin in Liberty State Park.29 Hinsdale’s first proposal for Tilyou—a “Palace of Pleasure”—was a lavish confection straight out of Second Empire Paris. The Pavilion of Fun was sheet cake in comparison, reminiscent in its massing of one of the earliest iron-and-glass shed structures—Gabriel Veugny’s 1824 Marché de la Madeleine in Paris. If it broke no new ground as a type, Tilyou’s Pavilion of Fun was unprecedented in that it made Steeplechase the first amusement park in the world to bring under a single roof a vast range of amusement rides and attractions. It remained the largest such structure anywhere during its life, surpassed only by the ill-fated Old Chicago mega-mall and indoor amusement complex that opened in the Chicago suburb of Bolingbrook in 1975 (and closed five years later).

George C. Tilyou’s Pavilion of Fun, its scale wildly exaggerated in this 1908 postcard, brings Sam Friede’s “collection of amusements in midair” down to earth. Collection of the author.

Tilyou would be loath to admit that Friede’s orb was floating across his sagittal plane as he contemplated the Pavilion of Fun. But even a cursory comparison reveals striking parallels. For all its absurdities, Friede’s sphere was probably the first self-contained, self-enclosed theme park ever proposed—certainly it was the first to gain widespread publicity. The Steeplechase shed was a kind of pancaked, economy version of Friede’s soaring “Department Store of Amusements.” Indeed, Tilyou himself described his Pavilion of Fun as an “Amusement Emporium.” And like the star-crossed orb, it was outfitted with a grand ballroom, probably the largest in the city when it opened. It, too, had a palm garden and an observatory, just like the Globe Tower. Tilyou may well have even adopted Friede’s business model to help pay for the great building—by incorporating and selling shares of stock. Tilyou had never done this before. Yet now, in February of 1908, he incorporated Steeplechase Park, capitalizing it at $2 million and authorizing the issue of 400,000 shares of stock. A quarter of these he proposed to sell to the public. He was scrupulously transparent and democratic about it, the specter of Friedean fraud no doubt in mind. As the Billboard reported, “Many of Mr. Tilyou’s friends have urged him to let them into this money-making investment through the organization of a stock company, but Mr. Tilyou has taken the position that he can show no partiality. His friends, he says, are the public, and if he lets any in on such a deal it will be the public or nobody; and if the public it would be through a system of small shares of one or five dollars or so that would enable the poorest of his old patrons to realize well on their investment.” He was also swift to share the wealth, declaring an 8 percent dividend in October and sending out “a barrel of checks” to his big and little backers. The master showman also sweetened his stock with something Friede could never offer: each dollar certificate was also an admission ticket to Steeplechase.30

In the end, for all the outrage and indignation the Friede Globe Tower hoax provoked, its context must never be forgotten. This was Coney Island! The counterfeit palace, an island fantasy built out of smoke, mirrors, and windblown sand, a place where nothing was what it seemed and artful sleights of hand were the coin of the realm. Coney Island had been relieving honest folk of cash and morals since almost the day the Dutch first spied its namesake rabbits. Here was an empire of illusion and altered reality—the “apotheosis of the ridiculous,” as Reginald Wright Kauffman put it the very year Tilyou dynamited Friede’s footers. The seductions of Coney Island required a temporary suspension of one’s faith in fact and veracity. And it was above Coney Island’s bewitching mix of reality and the absurd that Samuel Friede floated his marvelous steampunk orb, an apparition that vanished at first light—“a beautiful bubble,” eulogized the Eagle, “burst before the eyes of a long list of optimistic Brooklyn investors.” The Globe Tower was no crime against New Yorkers, no black mark on the good name of Coney Island; it was the undiluted essence of the place, a trick played on the tricksters, the biggest joke of all.31