CHAPTER 9

PORT OF EMPIRE

I’d like to take a

Sail on Jamaica

Bay with you,

And fair Canarsie’s Lakes we’ll view . . .

—ROGERS AND HART, “MANHATTAN”

From the long-vanished footers of the great Globe Tower, it is but a short walk today to the corner of Shell Road and West Sixth Street. Framed by used car lots and a large commercial laundry, the spot is anything but picturesque—a scruffy crossroads on the way to the beach. And yet here one may glimpse, like strata exposed, multiple layers of Brooklyn’s past. Shell Road is the southernmost extension of McDonald Avenue, a major commercial artery that plunges down the map from Green-Wood Cemetery through the heart of Gravesend’s ancient grid. Beneath the asphalt here (and occasionally peeking through) are the buried rails of the Prospect Park and Coney Island Railroad, a streetcar line that began operating in 1875. Overhead roars the Belt Parkway on its way to the Narrows; above that runs the F train, clattering and screeching. And back on the ground, just beyond the cracked sidewalk and the ailanthus-tree sprouts, is water—the stagnant, bulkheaded terminus of Coney Island Creek. Litter-bobbed and reeking, it is nonetheless a storied channel; for the creek separates Coney from mainland Brooklyn, thus making it an island. It’s perhaps best known today for a half-submerged, barnacle-encrusted submarine—the Quester I—resting in shallow water just off Calvert Vaux Park. Built in 1970 by a Navy Yard shipfitter named Jerry Bianco, it was part of a mad scheme to raise the Italian ocean liner SS Andrea Doria off the Nantucket sea bottom (by injecting its hull with inflatable air bags). In the spirit of Sam Friede, the project was funded by the sale of shares of stock in a company called Deep Sea Techniques. Though the craft won coast guard and navy approval, it capsized upon launch and never got beyond its birth chamber.

Sunken vessels in Coney Island Creek, 2017. The wreck of the Quester I is at lower right. Photograph by author.

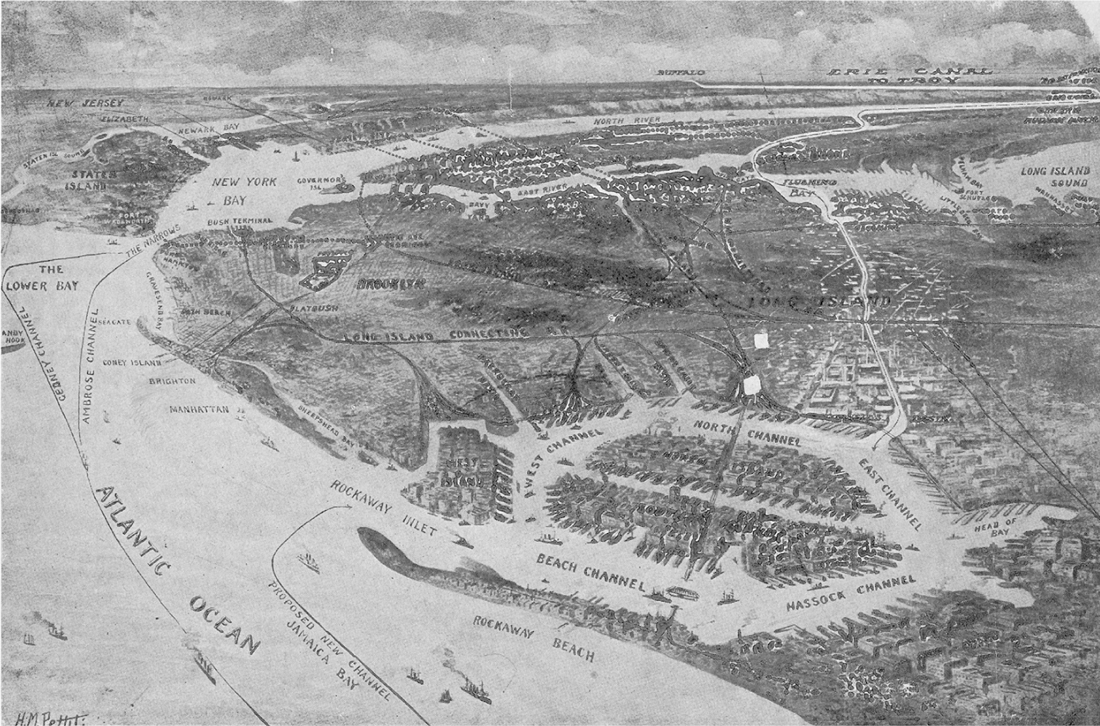

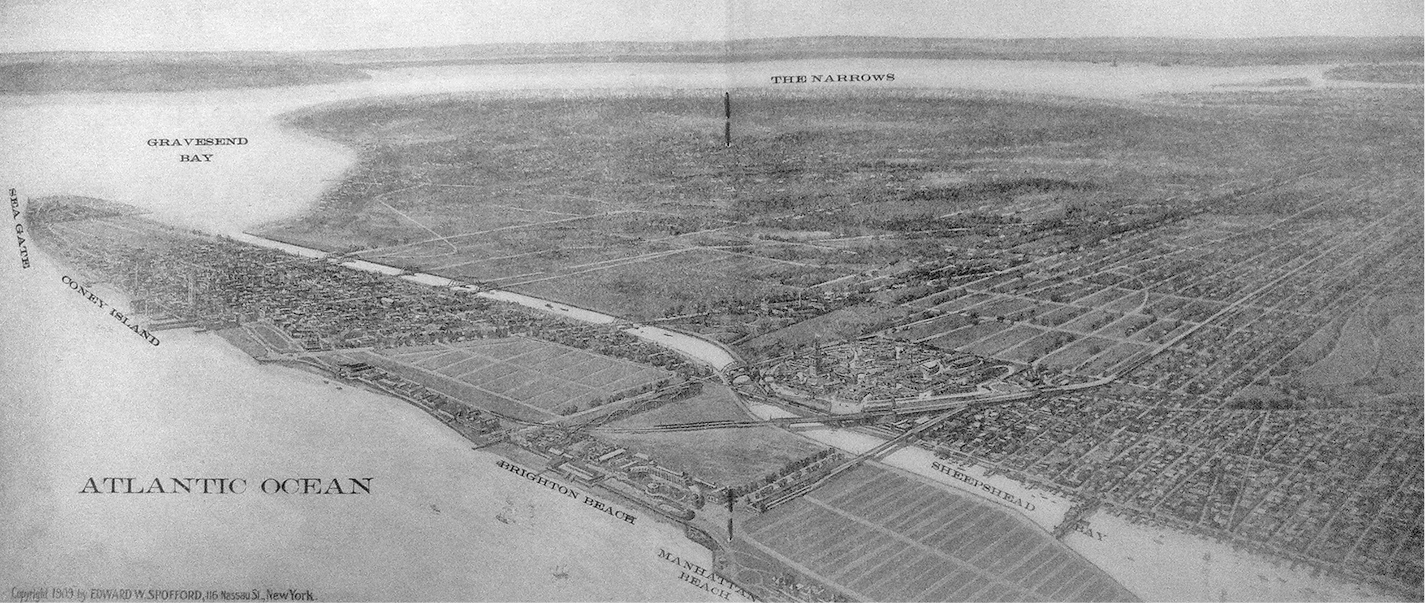

Coney Island Creek once plied a meandering course between Gravesend Bay and Sheepshead Bay and was navigable by small craft as late as 1915. Even then it was no enchanting rivulet; the Brooklyn Standard Union described it as “a nuisance and eye-sore, winding its noxious way . . . serving no useful purpose whatever.” Nonetheless, the creek once hovered on the verge of fame; for its waters were to serve one of the most heroically misguided infrastructure projects ever proposed for New York City—the “Great World Harbor” that would turn Jamaica Bay into the largest port on the seven seas. A stone’s throw from Ambrose Channel and the “four-fathom curve”—the isobath or contour indicating the depth at which most coasting vessels will not run aground—Jamaica Bay was touted as America’s front door to the Atlantic. As Harry Chase Brearley observed in his 1914 treatise The Problem of Greater New York and Its Solution, the forty-five square miles of Jamaica Bay made it large enough to absorb “the principal portions of the harbors of Liverpool, Antwerp, Hamburg, and Rotterdam . . . without undue crowding.” In his view the bay was a godsend for Gotham—“a physical fact of compelling proportions,” he wrote, and “one of the dominating geographical features of Greater New York.” New Yorkers got a first glimpse of what that geography might become on March 13, 1910. That morning, the New York Times ran an article headlined, “JAMAICA BAY TO BE A GREAT WORLD HARBOR,” accompanied by a breathtaking aerial view of the port-to-be by the celebrated artist and illustrator Vernon Howe Bailey. In a literal flight of the imagination, Bailey depicted Gotham not from the usual Manhattan vantage, but from seagullian heights far above the rolling surf of Rockaway Beach. In the center of Jamaica Bay a pair of islands sidle up to one another like whale pups in a great amniotic sac. Fringed with cilia-like wharves, the islands resemble mini-Manhattans, progeny of the great city slumbering on the horizon. The projected seaport was as breathtaking as it was visionary. Here the world’s merchant fleet would find hundreds of miles of harborage on the edge of America’s greatest manufacturing city. On its western edge at Barren Island a series of great piers would be built, each 850 feet wide and 8,000 feet long—bigger than anything in North America at the time. As many as fifty vessels could berth at any one time. The port would be developed in stages; until more room was needed, why not turn the bay’s marshy hummocks into a great water park? John Charles Olmsted, stepson of the designer of Prospect and Central parks, suggested just that: a low-slung realm of “lagoons and wooded archipelagos.” Harold Caparn, who later helped design the Brooklyn Botanic Garden, envisioned an expansive playground: “Not a conventional park, with lawns and exotic trees and shrubs,” he explained, “but a water-park with many and intricate channels intersecting the great level areas of reclaimed marsh, on which all the sports of smooth water . . . may find ample space.”1

All this struck a chord with New Yorkers worried about Gotham’s future as America’s leading port city. By the end of the nineteenth century, the city’s aging port infrastructure—much of it built before the Civil War—could hardly keep up with the flood of goods pouring into town. New York was the entrepôt through which nearly half of the total foreign commerce of the United States passed annually. The value of goods entering and clearing its port jumped from $620 million in 1875 to $1.2 billion in 1905, while tonnage in foreign trade more than doubled—from 8.73 to 18.9 million tons—in that same period. These concerns gained urgency once the United States began work on the Panama Canal in 1904, for it was widely assumed that seaborne custom would surge once the isthmus was crossed. New port facilities were needed beyond Manhattan, and Jamaica Bay seemed an ideal place to build a seaport equal to the ambitions of the newly consolidated city. Long overshadowed by worldly Manhattan, Brooklyn might well now hold the keys to Gotham’s future. As John E. Ruston of the Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce put it, Jamaica Bay was “the potential savior of the commercial pre-eminence of the port of New York.” At first flush, it seemed to offer much indeed, with twice the water frontage of Manhattan from Hell Gate to the Battery and up the Hudson to 135th Street. The Coney Island Canal—and an even more ambitious ditch from Jamaica Bay north across Queens to Flushing Bay on Long Island Sound—were deemed essential to this vision; for they would make the World Harbor part of a weather-safe inland passage from the Hudson River to the sea. Because the New York State Barge Canal—the modernized, much-expanded successor to the famed Erie Canal—meets the Hudson just below Albany, these canals would effectively tie the new seaport into a mighty system of inland navigation that, with Lake Erie, would reach some eight hundred miles into the American heartland. Shipments of grain, ore, coal, or lumber could be barged from as far away as Detroit or Cleveland without ever touching land or hazarding open coastal waters. Jamaica Bay would be not only Gotham’s portal to the world, but America’s.2

The Great Port of Jamaica Bay on cover of a commemorative dinner program, 1912. Buttolph Collection of Menus, Rare Books Division, The New York Public Library.

From above, Long Island resembles a great split-tailed fish, with Prospect Park for an eye and Jamaica Bay a gaping mouth. As we’ve seen, it was shaped by that great sculptor of New York State—the Laurentide ice sheet that made its last sortie out of the Canadian arctic some twenty thousand years ago. The glacier crept down the map, withdrew, and advanced again, leaving behind Long Island—a sea-swamped moraine pushed forward by the ice and left behind after its last retreat. As the glacier began melting, sand and silt were carried seaward, creating the broad outwash plain of Long Island’s south shore. Jamaica Bay was a delta at the mouth of a river of glacial meltwater that subsequently flooded as sea levels rose at the end of the Ice Age. Ocean currents, tidal action, and storms further shape-shifted the sands, eventually extending Rockaway Peninsula—the westernmost end of the sandy archi-pelago that parallels Long Island’s south shore—to create a long, sheltered entrance to Rockaway Inlet. Thus shielded from the fury of the Atlantic, Jamaica Bay developed an extraordinary diversity of plant, animal, and marine life. Upland areas were dominated by sumac, blueberry, holly, and cedars; salt marshes supported a myriad of native grasses and were laced and drained by an array of tidal creeks. The abundance of marine and animal life in and around Jamaica Bay provided sustenance for native peoples long before Hudson’s Half Moon appeared on the horizon. The name Jamaica has nothing to do with the Caribbean island nation (despite Brooklyn’s large West Indian population), but—like so many place-names in metropolitan New York—derives from the Lenape word yemacah—“place of the beaver.”3

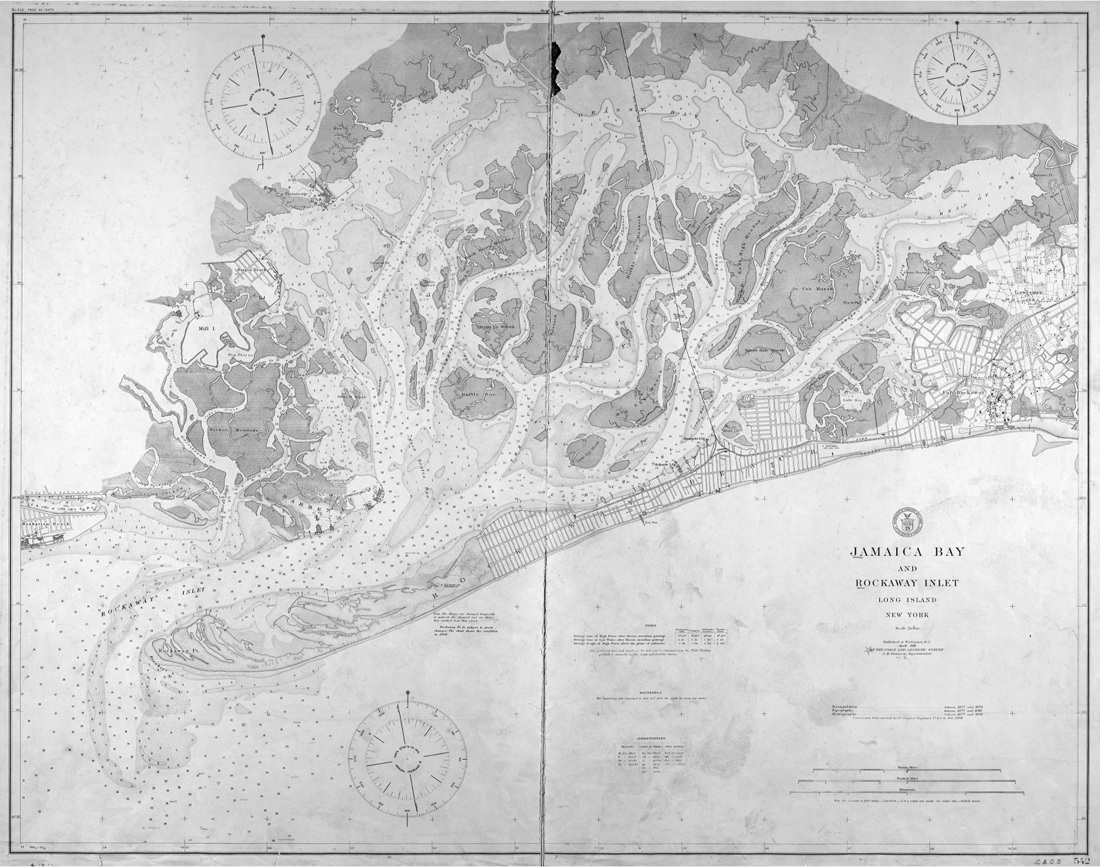

Tucked behind the sheltering arm of the Rockaways (from the Lenape Rechqua Akie) Jamaica Bay fairly leaped off the map as a would-be seaport. Brearley described the bay as “not only shore-enclosed, but vestibuled as well,” a harbor whose waters were protected “so thoroughly from the ocean that while a heavy surf may be thundering at the beach, the surface of the bay is scarcely rippled.”4 The frailest craft would find safe shelter within. Exactly who first advocated making Jamaica Bay a great world port is unclear, but it may well have been that Zelig-like Gotham visionary Andrew Haswell Green—the autocrat who helped create Central Park, even as he drove its designers mad. Though nothing of Green’s writings on Jamaica Bay survive, we know of his dreams for a port there from a 1909 speech by Joseph Caccavajo—a prominent civil engineer with an interest in city planning. In a lecture to the Brooklyn Allied Boards of Trade and Taxpayers’ Associations, Caccavajo related an encounter with an elderly man on a train some eight or nine years earlier (circa 1900). “This old gentleman,” he told his audience, “was Andrew H. Green, the father of Greater New York, and I shall never forget the earnest manner in which he told me that I would probably live to see New York City extend north to Dutchess County and east to absorb all of Nassau and a good portion of Suffolk County.” Caccavajo was particularly spellbound by Green’s prediction that within a generation “Jamaica Bay would be the greatest shipping center in the world . . . connected with the East River and Long Island Sound by a great ship canal across Queens Borough to Flushing Bay” and another “back of Coney Island connecting Jamaica Bay with Gravesend Bay.” The octogenarian seemed so certain about the future of the bay and “spoke so enthusiastically of its possibilities,” Caccavajo recalled, “that a few days after our meeting I visited Jamaica Bay, and later . . . prepared some preliminary plans for its improvement.” Caccavajo’s work has since been lost but was likely the earliest scheme for a seaport at Jamaica Bay.5

“Not only shore-enclosed, but vestibuled as well.” Jamaica Bay and Rockaway Inlet, 1911, United States Coast and Geodetic Survey. Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division, The New York Public Library.

Caccavajo eventually moved on to other things, planning routes for the city’s first rapid transit lines. But the seaport scheme soon found an even more passionate promoter in the person of Edward Marshall Grout. Dubbed the “Longheaded Politician” for his shrewdness and scholarly mien, Grout was a New Yorker of old Yankee stock and the prosecutor who put Gravesend autocrat John Y. McKane behind bars. He later became Brooklyn’s first borough president and ran successfully for comptroller of the city of New York in 1901 on an anti-Tammany fusion ticket with Seth Low. It was as comptroller that Grout submitted a proposal to the Sinking Fund in 1905 for the development of Jamaica Bay, which awaited only the hand of man, he believed, to become “a commercial and manufacturing Venice, or a Venice of homes, or both.” Transforming this vast expanse of “waste land and water” into a great seaport was an idea Grout had been mulling over for years. “My proposition,” he wrote, “is that the City should at once take up, formulate and execute a comprehensive scheme for the full development of this property . . . by reclaiming the salt marshes, filling in the shallow parts and hummocks of the bay, bulkheading the islands and shores throughout the entire extent, and opening up such channels between the filled-in lands as may best develop the locality.” Creating new land could be done cheaply enough, for filling and bulkheading could be “easily accomplished from the waste products collected by the Department of Street Cleaning . . . and perhaps by the use of the excavated material from future rapid transit subways.” By developing Jamaica Bay, Grout concluded, the city would help “furnish here a centering point for great manufacturing interests.” Grout could well be suspected of Brooklyn boosterism (he had been the borough’s first president, after all). But his real interest was the continued supremacy of New York as a center for shipping, trade, and commerce, particularly the “absolute need of increased water front and dockage facilities in the port of New York at cheap rates.”6

By the time Grout made his proposal, Jamaica Bay was alive with craft—garbage scows, barges, trollers, fishing skiffs, ferries carrying passengers to and from the Rockaways. But except for ships hauling fertilizer to Europe, it only rarely saw an oceangoing vessel, or even those plying coastal waters. Most goods shipped from Flatlands, Canarsie, and other towns typically went overland to Brooklyn and thence by ferry to Manhattan. The shores of Jamaica Bay were still largely in a wild state, with little more than ferry docks and stilted shacks. Of course, Brooklyn had elsewhere developed an impressive array of port facilities by this time, mostly clustered on the borough’s northwest shore along New York Harbor. Many dated to the earliest years of colonization. Merchant vessels were being built in Wallabout Bay in the 1780s, later the site of the Brooklyn Navy Yard. Warehouses, piers, and a ferry terminal were built at the foot of Brooklyn Heights, across from lower Manhattan. Farther south, Erie Basin in Red Hook was developed in the 1850s by William Beard. One of the largest artificial harbors on the Eastern Seaboard, it served as a terminal for grain and other products shipped via the Erie Canal. On the south side of Gowanus Bay was Brooklyn Basin, where Edwin Clark Litchfield’s Brooklyn Improvement Company dredged Gowanus Creek into a mile-long canal that received—among many other things—the barge-loads of brownstone used to build Brooklyn’s iconic row houses. The canal was lined with lumber, brick, and coal yards. Farther north, on Brooklyn’s border with Queens, Newtown Creek Canal stimulated industrial development in Greenpoint and Williamsburg, and was originally meant to be extended south across Bushwick and Brownsville to join Jamaica Bay at Canarsie (both Gowanus and Newtown creeks are Superfund sites and among the most polluted waterways in the United States). By the 1890s these improvements helped make Brooklyn one of America’s leading port cities. As Henry R. Stiles enthused, they “attract hither the commerce of the world,” granting Brooklyn “supremacy over all other cities on this continent.” On the eve of Consolidation, the city’s portfolio of port and manufacturing facilities gained one last diamond—Bush Terminal, America’s first multitenant, intermodal industrial complex. Construction on the vast project began in 1895 and eventually spread over two hundred acres of Brooklyn’s waterfront, just below Sunset Park. Some twenty-five thousand workers were employed in Bush Terminal’s shipping, warehouse, and manufacturing plants. In developing his namesake complex, Irving T. Bush exploited the Achilles heel of port operations in Manhattan. For despite its splendid piers and wharves, getting goods into and out of the port had become a time-consuming and costly affair.7

But even with Bush Terminal, the Port of New York was at capacity, and the specter of losing trade to competitors made Grout’s Jamaica Bay proposal compelling indeed. Historically the hub of shipping activity in the city, Manhattan Island is blessed with deepwater portage on both the Hudson and East rivers, allowing oceangoing vessels to tie up a stone’s throw from the center of commerce. But what served well in a slower age of sail proved inadequate as ships grew longer and the pace of commerce increased. The city faced a dilemma of abundance. On the eve of the First World War, New York was America’s busiest port, handling half of all the foreign commerce of the United States. In 1914 alone, 120 million tons of freight passed through the port by ship and rail. But the very geography that made Manhattan so accessible to the world isolated it from the rest of the country, with serious implications for commerce. The nation’s mighty rail network ended in a great ganglion of tracks in Bayonne and Hoboken. “Eight of the twelve railroads on which Manhattan, Brooklyn, Queens and the Bronx depend,” wrote William R. Wilcox in a 1920 report that presaged formation of the Port Authority, “are on the New Jersey side of the Hudson.” All goods arriving in port had to undergo a grueling transfer process to make it to the railheads, save only those to be consumed in Manhattan or shipped upstate via the New York Central Railroad—the only line with a direct freight connection to Manhattan. The others were forced to lift their goods-filled boxcars by gantry crane onto barges (known as “float bridges” or “car floats”) to be tugged—a handful at a time by the venerable New York Dock Railway—to the railheads across the river. Transferring freight between truck, ship, and train created choke points that slowed the movement of freight, drove shipping costs through the roof, and bred all sorts of crime and racketeering. Longshoring—loading and unloading ships—soon accounted for 50 percent of a ship’s total expense in moving cargo. This made a large labor force vital to the transshipment process, one that organized into one of the most powerful unions in the city—the International Longshoremen’s Association. The rough, racket-ridden world of the longshoremen—memorably depicted in the Marlon Brando film On the Waterfront (actually shot in New Jersey)—was itself largely a function of Manhattan’s isolation from the mainland and inadequacy as a modern seaport. “There has never been a loading racket in San Francisco, in New Orleans, in Baltimore or Philadelphia,” wrote Daniel Bell in The End of Ideology, for “the spatial arrangements of these other ports is such that loading never had a ‘functional’ significance.” Each enjoyed a direct connection to trunk-line railroads, enabling easy transfer of cargo to the nation’s rail grid, while none had to struggle with the “congested and choking narrow-street patterns” that made Manhattan’s piers so difficult to access. As William R. Wilcox cogently summarized it in a 1920 report, “Our port problem is primarily a railroad problem.”8

One of the most lucid assessments of New York’s looming port crisis was made in 1908 by George Ethelbert Walsh, a writer better known for romances and children’s books. In a piece for Cassier’s Magazine, Walsh pointed out what every longshoreman knew well: “The Island of Manhattan is too full”—not only of people, but “too full of freight traffic. Its streets are arteries through which the life-blood of the nation often stagnates instead of flowing steadily in a limpid stream. From terminal to terminal, and from pier to pier, the great freight stream pours, crossing and re-crossing, and often making wide detours to reach its destination.” East side and west, the call from the wharves was for ‘room, and more room’!” Studies at the time revealed that all available wharfage in New York would be exhausted in ten or fifteen years. Manhattan was also increasingly fettered in its ability to handle large passenger ships—a situation that came to a head in early 1911 when the War Department refused the city permission to extend its Hudson River steamship piers by two hundred feet. The request was made when the Dock Department learned that two ships of the White Star Line—the Olympic and the Titanic, each over nine hundred feet in length—would be making maiden voyages to the city within months (the Olympic would arrive in June; the Titanic sank, of course, en route the following April). The War Department ruled that extending the piers would narrow the channel, impeding navigation on the river and possibly increasing the river’s rate of flow—a kind of hydraulic Venturi effect. The permit denial brought joy to Brooklyn, for it already boasted the city’s longest piers—at Thirty-First and Thirty-Third streets in Bush Terminal, where the Dock Department planned to build several more ranging in length from twelve hundred to seventeen hundred feet. The thousand-foot steamship crisis underscored the need for a modern port; for the “real need,” opined the Sun in December 1912, “is not merely to meet the emergency of the moment affecting one class of shipping—but to devise and adopt a system of port development that shall preclude forever . . . the possibility of other emergencies.”9

Brooklyn’s working waterfront, 1918, site of Brooklyn Bridge Park today. William D. Hassler Photograph Collection, New-York Historical Society.

Grout’s proposal for an alternative port at Jamaica Bay gathered little dust. Within months of publication, the Board of Estimate and Mayor George B. McClellan, Jr., formed a Jamaica Bay Improvement Commission. Its exhaustive Report, released in the summer of 1907, surveyed a gamut of issues related to Gotham’s economic growth—manufacturing output, import and export activity, shipping tonnage, population growth—and the “probable demands” these would place upon the city’s port facilities. The commissioners found the port operating at a mere quarter of the efficiency of Antwerp’s. Not only was Manhattan difficult to reach; it offered few warehouses close to piers and wharves. This “spatial mismatch” between berth and warehouse caused endless, costly schlepping across town. The Manhattan merchant was “obliged to proceed to some pier or several,” reported the commissioners, “secure his consignment of material, truck it over miles of city streets to the warehouse or factory, unpack it, sort it, make it up, repack and again truck it back to the wharves for shipment.” They, like Walsh and other analysts, concluded that Manhattan simply could not sustain an upsurge of port activity. Efforts to increase its efficiency—by building, for example, the Chelsea Piers, embellished by the architects of Grand Central Terminal—would only delay the inevitable. Manhattan was maxed out. Indeed, “the City has arrived at that point,” they concluded, “where it is necessary for her to reach out and take advantage of the vast amount of water frontage which she possesses in her other boroughs”—such as Jamaica Bay. The Brooklyn press heartily concurred. “If New York continues its great stride,” editorialized the Standard Union, “much of the growing shipping must go either to Newark Bay or Jamaica Bay and naturally this city wants the latter to have it.” Or, as George Walsh put it, “The development of Jamaica Bay into a great basin for the docking of ocean steamers, where deep-sea freight can be transferred directly to cars, would undoubtedly eliminate many of the evils which congest the City and river fronts of to-day.”10

Adding further weight to arguments in favor of a Jamaica Bay seaport was the upsurge in shipping widely—and hopefully—expected to come with completion of the Panama Canal. It is no coincidence that Grout’s proposal was written in 1905, the first full year of American work on the big ditch. The Panama Canal was the moonshot of its age, the most ambitious civilian works project in US history until the Apollo space program. Crossing the Panamanian isthmus had been a dream of seafarers and imperialists since the sixteenth century. It was especially seductive to American merchants, for it would eliminate the treacherous journey around Cape Horn that made traveling by ship between the East and West coasts of the United States a long and costly affair. Cutting across the isthmus halved the distance between New York and Los Angeles. “Canal fever” began spreading as the United States took over control of the project from the French, sped by the Pan-American Union’s “Get Ready for the Panama Canal” campaign. Cities up and down both coasts upgraded their ports for the expected flotilla of canal-borne traffic, even building canals of their own in emulation of the federal effort. New Orleans dug the Industrial Canal between the Mississippi and Lake Pontchartrain; Texas deepened its Houston Ship Channel. New York upgraded the old Erie Canal, an infrastructure that profoundly altered the regional economies of the Northeast in the mid-nineteenth century but by 1900 was as obsolete as a dirt airstrip in an age of jets. The New York State Barge Canal—approved by voters two weeks before the United States and Panama signed the treaty creating the Canal Zone—was meant to modernize and expand the Erie system, deepening and rerouting the original channel and adding three new ones: the Champlain, Oswego, and Cayuga-Seneca canals. Together, the upgraded system formed “a continuous highway for interstate and foreign commerce” spanning eight hundred miles.11

The author’s grandfather, Giovanni Tambasco (below boom, farthest to the right in pit), on steam-shovel crew excavating the New York State Barge Canal in Madison or Oneida County, New York, 1908. Collection of the author.

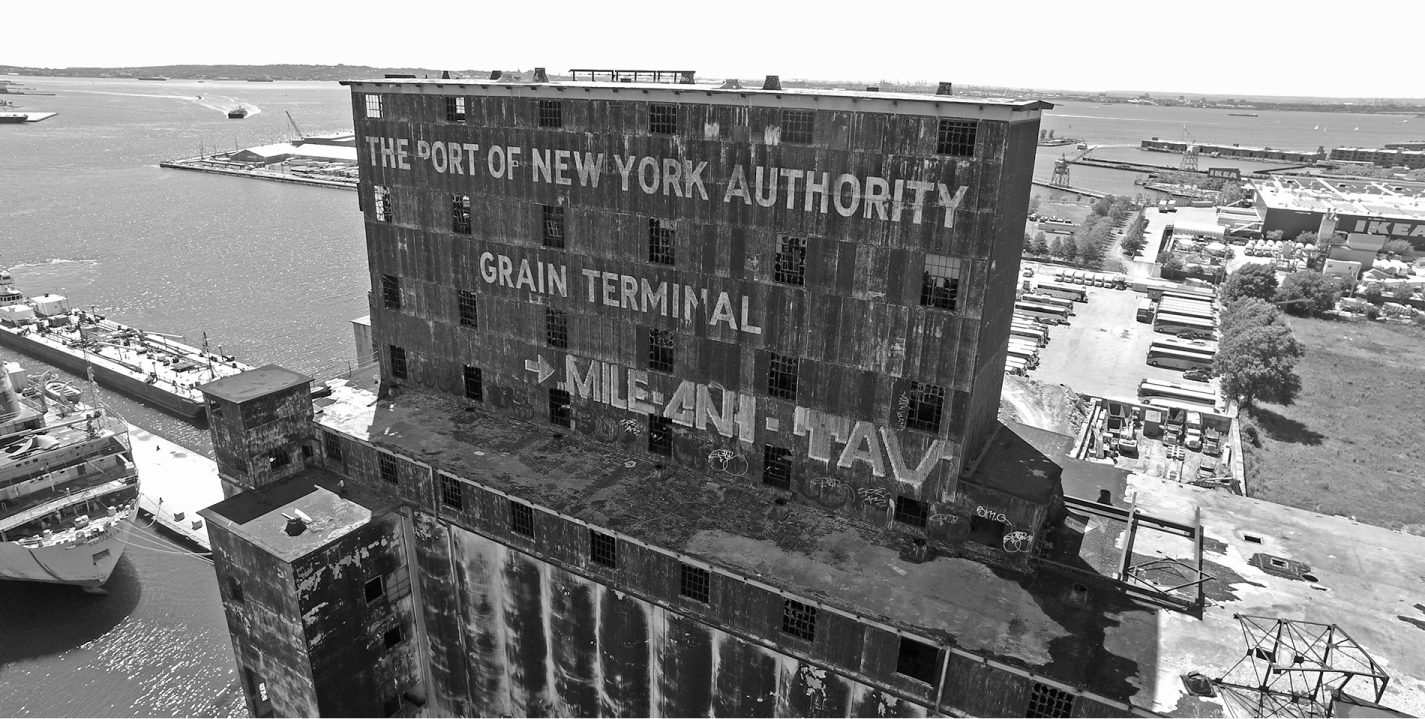

However extensive its inland reach, the State Barge Canal would be only as good as its terminal in New York City, its gateway to the world. Gotham was admonished to help ready the Empire State, and not allow complacency and “its colossal egotism” to impede implementing necessary improvements to its port. John Barrett, director general of the Pan-American Union, worried in 1912 that the great metropolis, “overconfident in its magnificent power and position,” had not stirred “to make the same effort to get ready for the [Panama] canal or to develop its commerce with Latin America as are Boston, Philadelphia, Baltimore, New Orleans, Los Angeles, and San Francisco.” But enhancements were made, however few and slowly. Erie Basin, terminus of the Erie Canal, was upgraded as one of several official Barge Canal stations in the city. The improved basin and adjacent Gowanus Canal could handle, among other craft, the twenty-five-hundred-ton ships of the Pacific Coast Lumber Company, which hauled timber from Oregon and Washington through the Panama Canal and onward to Chicago via the Barge Canal. Soon new canal terminals were under construction on Newtown Creek, Flushing Bay, at Rogers Street in Long Island City, Hallet’s Cove in Astoria, Mott Haven in the Bronx, and in Manhattan at West Fifty-Third Street and Pier 6 on the East River. This last facility, at the foot of Coenties Slip (today’s Downtown Manhattan Heliport) was the first completed. Described as “immaculate in white paint and with electric lights gleaming along the sides,” the facility was opened by Governor Al Smith in October 1919. An even more substantial improvement was made in Brooklyn—a huge grain elevator at the foot of Columbia Street on Gowanus Canal. Previously, the only grain storage facilities in the city were owned by the railroads, mortal enemies of canals. Grain arriving in New York by canal boat was thus forced to sit for days on barges, to the joy of the local vermin population. Industry and city leaders feared that New York was ill prepared to handle the expected surge in Midwest grain shipments once the Barge Canal was completed—that the city would lose the grain trade just as it had earlier lost the cotton and tobacco trades. Gotham’s biggest competitor in this was Montreal, which had plenty of grain elevators at its disposal. Montreal built its first storage facility in the 1850s and erected five modern grain elevators between 1900 and 1930. By then its elevator capacity was a staggering eighteen million bushels—enough wheat to make 756 million pounds of pasta (twelve servings of spaghetti for every person in America today). Gotham had fallen hopelessly behind its northern neighbor, prompting frantic action by officialdom and industry. “The crying need,” wrote the state’s chief engineer, Frank M. Williams, in 1919, “is for an elevator in New York.” The New York State Barge Canal Grain Elevator, completed in 1922 with capacity for two million bushels, was the somewhat meager and belated answer to this call. The derelict structure still dominates the Red Hook skyline.12

But these terminals in New York City were small and designed to handle primarily domestic trade. For the Barge Canal to really shine—to become infrastructure of global consequence—required a great deepwater seaport, a “general terminal for the accommodation of export trade” that could handle a fleet of oceangoing vessels. As Nelson B. Killmer of the Harbor Protective and Development Association stressed, “success of the export business over the canal” required a separate terminal for seaborne trade in New York City, one segregated from “local and coastwise business” and with “plenty of room where transshipment can be made quickly and cheaply.” The Jamaica Bay seaport would give the Barge Canal access to the world, while itself drawing sustenance from the canal’s eight-hundred-mile taproot into the American heartland. Consummating this union, however, required not only vast internal improvements to Jamaica Bay (dredging channels, filling marshes, building bulkheads, piers, and wharves), but construction of two crucial last segments of the Barge Canal itself—the Coney Island Canal, from Gravesend Bay to Jamaica Bay, and a considerably longer channel north from Jamaica Bay across Queens to Flushing Bay. These canals would provide convenient weatherproof connections to the bay from New York Harbor and Long Island Sound. While Jamaica Bay could be accessed by sailing around Coney Island, this open-water route was reliably safe only in summer. Winter months exposed barges and canal boats—craft designed for placid waters, vulnerable to swamping when heavily laden—to the constant menace of storms. The Flushing Canal would similarly make access to Jamaica Bay easier for craft plying the coast from New England, which were forced to either navigate the treacherous Hell Gate or steam all the way around Long Island on open seas. As Noble E. Whitford explained in 1921, Jamaica Bay could never develop into a port of consequence without these links, for “safe water communication was . . . essential, even indispensable to the success of the project.” Together, the channels would give canal men “a continuous waterway,” noted the New York Times, “from the northern part of the State to the principal landing place of the ocean steamers.”13

The derelict New York State Barge Canal grain elevator on the Red Hook waterfront, 2018. Photograph by author.

Proposed Coney Island Canal linking Gravesend Bay to the Great World Harbor via Sheepshead Bay. From E. W. Spofford, Views of Picturesque Sheepshead Bay (1909).

The Coney Island and Flushing canals would be the only segments of the Barge Canal not directly linked to the rest of the system, and the only saltwater canals in New York State aside from a short passage between Shinnecock and Peconic bays built in 1892. Saltwater canals present unique hydrographic challenges owing to the effect of tides, which can vary considerably at opposite ends of the channel. This was only a minor issue with the Coney Island project, which simply improved a natural waterway. It also required no locks to negotiate terrain, and because the Gravesend and Sheepshead Bay sections of Brooklyn were still only thinly settled at the time, land acquisition would be easy. Compared to the Flushing project, making Coney Island Creek a canal was a cakewalk. Indeed, just such an improvement had been floated long before the Jamaica Bay seaport project. In 1864 the Kings County Land Commission proposed a two hundred-foot-wide ship canal to Sheepshead Bay, flanked on both sides by grand avenues a hundred feet wide. But there was one serious problem at Coney Island—the tremendous amount of traffic that would have to be carried across the canal daily to and from America’s most popular seaside resort. Tens of thousands of New Yorkers flocked to Coney Island’s amusement parks and beaches on a summer day, most via public transit. “If enlarged and made a highway for small craft,” complained the Brooklyn Standard Union in 1918, “the delays which passenger traffic would suffer . . . would be irritating beyond measure.” Costly bridges would be needed all along the channel. Regardless, the canal was authorized by the New York State Legislature in 1919, with an appropriation of $883,000 recommended the following year by the Gravesend–Jamaica Bay Waterways Board to purchase the necessary 400-foot-wide right-of-way. This would enable construction of a channel 250 feet wide and 15 feet deep. As predicted, getting all that beach traffic over the new channel would cost a king’s ransom: the bascule bridges recommended by the Waterways Board were estimated at more than $9 million.14

Canal Avenue, Coney Island. Photograph by author, 2018.

The Flushing Bay canal presented far more serious engineering and logistical challenges. To begin with, it was four times longer than the Coney Island Canal. Three alignments were studied, each leading north from the vicinity of today’s John F. Kennedy International Airport. Two were dropped because of engineering complexity and cost. The route eventually chosen followed Cornell Creek from Jamaica Bay inland toward Baisley Pond (which the long-buried waterway still drains today in a culvert). Prior to airport development, Cornell Creek meandered lazily through the salt marshes toward the bay, making a last slow bend where Concourse C of Terminal 8 stands today (the Swatch Store by Gate 38 sits roughly above the creek’s old west bank).15 From Cornell Creek the canal was to pass near the junction of 109th and Lakewood avenues, and from there run just east and parallel to today’s Van Wyck Expressway. It would join the channelized Flushing River—the “small foul river” coursing F. Scott Fitzgerald’s valley of ashes in The Great Gatsby—about where Willow and Meadow lakes are today in Flushing Meadows Park. The canal was to enter Flushing Bay after crossing the central axis of the 1964 World’s Fair, just opposite that stainless icon of Queens, the Unisphere. But even this route meant an uphill battle with Long Island—literally. It does not take much topography to make canal building a challenging and costly exercise. Though the landscape north of Jamaica Bay rises gently for the first few miles, the sandy plain soon lifts to meet the great terminal moraine. At its highest point in Forest Park, the moraine rises more than one hundred feet above sea level—hardly a mountain, but serious elevation nonetheless for a boat road. There was no getting around this geological impediment; any north-south canal would have to go over, through, or under the broad rump of till.16

Three build alternatives were investigated. The first—a high-level canal—would rise and fall with the topography and thus require relatively little excavation. But multiple locks would be needed to negotiate the terrain, each requiring costly, temperamental pumps. And because much of the cut would not reach bedrock, the canal bottom would have to be sealed with concrete or “puddle” (a mixture of wet clay), adding further cost. The second option—a sea-level or “open-cut” canal—required only two locks, one at each end, and could rest on bedrock throughout.17 It was the cheapest of the alternatives, and the one favored by the state engineer. But it was hardly an easy build either; for cutting across Long Island at sea level would necessitate a colossal amount of earthmoving, resulting in a very deep (and thus very wide) cut that meant more land takings and larger bridges to carry streets across it. The third option—a tunnel canal—was estimated at nearly twice the cost of the sea-level route ($21 million, or about $500 million today), though it involved far less disruption of private property or the city’s street grid. The tunnel would consist of two parallel conduits, each fifty feet wide and made of steel and reinforced concrete. It would extend from Liberty to Union avenues, constructed with the “cut and cover” method employed on much of the New York City subway system. Added to these terrestrial challenges came one by sea—the dramatic tidal variation between Jamaica Bay and Long Island Sound. Low tide in Flushing Bay occurs some three hours before high tide in Jamaica Bay, with as much as six feet differential in tidal elevation at certain times of the year. This obviously made an unregulated sea-level canal impossible, for it would become a swift-flowing river several hours a day. But even a high-level canal would be subject to powerful diurnal currents. Canals and currents do not mix well, for fast water not only plays havoc with barges, but scours the canal bottom and transports sand that forms hazardous bars. Any of the canal types considered would require tidal locks with double-acting gates at both ends.18

Engineers could do little about a tide of another sort—of red brick and mortar—that threatened to quash plans for canals and seaport alike. South Brooklyn and much of Queens were still largely rural in the early years of the twentieth century, but not for long. World War I stoked a roaring national economy that helped unleash the greatest building boom in New York history. Vast sections of rural land were subdivided into streetcar and subway suburbs for the city’s prospering middle class. Every brick laid on mortar further diminished the chances that a canal would ever transit the neighborhood, for the immense cost and legal complexities of condemning such land made such a retrofit virtually impossible. And as homes sold, they filled with voters who could bring electoral doom upon any politician who supported unpopular land uses. Aerial photographs of Coney Island show nearly the entire projected canal alignment built up into shops, homes, and apartments by 1924. Though much of Queens was still being farmed at the time, it too was on the verge of development. Pockets of the borough, such as Forest Hills Gardens, had already become sought-after neighborhoods. As early as 1908, residents of Morris Park and Richmond Hill—upscale bedroom communities full of attractive homes—voiced opposition to the projected waterway, fearful “that a freight canal would cause many factories to spring up and injure the districts as home places.”19

But if canal promoters were in a race against the homebuilders, they also welcomed the anticipated surge of construction, touting it as a major reason itself for building the channel. As the New York Times concurred in 1912, “the great importance of the canal lies in the fact that it would provide for the transportation of lumber, cement, coal, and other material into the heart of Queens County and East New York and South Brooklyn, at a cost far below that over present routes of transportation.” Indeed, the very first cargo shipped to Jamaica Bay via the New York State Barge Canal was a boatload of 110,000 bricks delivered to the Howard Beach Building Company of Queens. The vanguard barge set out from the Aetna Brick Company in Crescent, New York, a hamlet on the Mohawk River, making its way through Barge Canal Lock No. 6 to enter the Hudson River at Waterford. It passed through New York Harbor some 175 miles later, was towed by the Narrows and Coney Island, and moored at Hawtree Basin on November 6, 1915. You would think the Lusitania itself had been resurrected and towed into port; for news of the lowly craft’s arrival made every paper in the city. Frederick W. Kavanaugh, president of Howard Beach, reported that shipping via canal was not only faster but cheaper—saving his company more than one dollar per thousand bricks over rail transport.20

By the time the brick barge made its sortie, both the Coney Island and Flushing canals were still dreams on paper. The New York State Barge Canal, too, was far from completion, delayed for years by administrative changes, engineering battles, and inept management. By 1914, some $100 million had been expended, with little to show and plenty to explain. “Has State or city benefitted by so much as a dollar?” asked the Evening World in an editorial that October. “On the contrary, Erie Canal traffic has been so hindered and hampered that east-bound tonnage to this city has fallen off more than two hundred thousand tons.” Even the mighty Panama Canal, launched the same year and one of the greatest engineering feats of all time, was completed before the New York project. Seas were joined in Panama, under budget and ahead of schedule, “while work on New York’s waterway has dragged along with scandalous slowness.” This was a particular embarrassment since the Panama Canal was one of the original motivations for both the canal upgrade and the Jamaica Bay seaport itself. Now the long-anticipated surge of trade was about to begin, and New York was still literally in the trenches. The opening of the Panama Canal meant that cargo could be shipped from California to New York and onward to Albany, Buffalo, Chicago, or Cleveland for less than what the railroads would charge to ship direct to final destination. But as Frank S. Gardner of the New York Board of Trade and Transportation admonished, the Barge Canal would have to be finished fast for all this to work in New York’s favor. Any further delay could lock the city out of newly forming flows of trade. “If by our own unpreparedness it is diverted into other ports like Baltimore, Norfolk, New Orleans and Galveston,” he warned, “it will tend to fix itself in those routes. We can never regain it, and our loss will be very great.”21

The New York State Barge Canal was finally inaugurated on May 15, 1918, some $70 million over budget and already out of date. In its first full year, the canal operated at a mere 10 percent of capacity, carrying just a million bushels of grain when the much more primitive Erie Canal had hauled thirty million bushels annually decades earlier. Within a generation the Barge Canal was effectively put out of business by the St. Lawrence Seaway, which gave cities on the Great Lakes an easy route to the Atlantic.22 If all this boded ill for the great seaport plan, its promoters faced even greater challenges of their own. First there was the bay itself. What appeared on maps to be a seaport-in-waiting was in reality full of shoals, shallows, and shifting sand—as Henry Hudson and his crew of the Half Moon may have learned that September day in 1609. This was, after all, the glacier’s outwash plain, not the deeply scoured troughs it left alongside Manhattan. Jamaica Bay’s fatal lack of depth was well known to colonial officials, and their successors would have done well to heed the total absence of positive commentary on the bay in early reports on provincial waters. Like the Dutch before them, the seafaring English knew a good harbor when they saw one, and they saw nothing of the sort in Jamaica Bay. One English writer even described such impassability as protection from marauders. In the first detailed account of New York by an Englishman, Daniel Denton remarked in 1670 that there were several navigable bays on Long Island’s north shore, “but upon the South-Side which joyns to the Sea, it is so fortified with bars of sands & sholes that it is a sufficient defence against any enemy.” In his 1678 study of navigable waters in the region, Governor Edmund Andros made no mention of Jamaica Bay. A decade later, Governor Thomas Dongan penned an extensive trade report on New York, affirming that in its waters “a thousand ships may ride here safe from winds and weather.” On the north side of Long Island, he pointed out, there were “very good harbors . . . but on the south side none at all.” William Tryon, provincial governor in the 1770s, was similarly mute on Jamaica Bay when queried about “Principal Harbours, how situated and of what extent.” Revolutionary-era charts with soundings for all New York Harbor and the Hudson and East rivers give none for Jamaica Bay—damning evidence indeed of its lack of suitability for maritime use.23

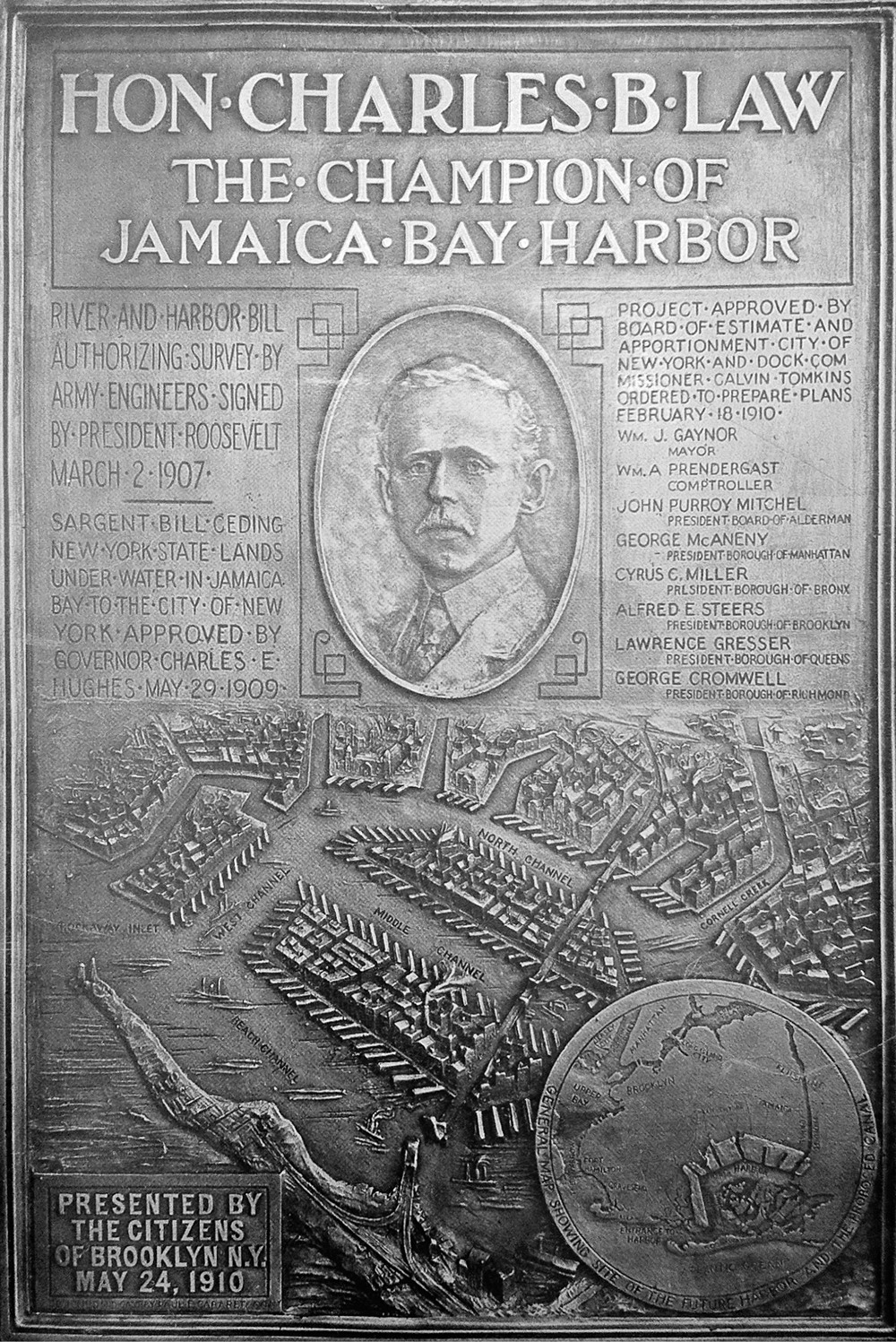

Making Jamaica Bay a deepwater port would require a Herculean dredging effort—so much so that General William L. Marshall of the Corps of Engineers, famed canal builder and dredger of Ambrose Channel, remarked that the project “practically amounts to the construction of an artificial harbor.” The federal government agreed to dredge the entrance through Rockaway Inlet, along with a thirty-foot channel around the perimeter of the bay—largely owing to the lobbying efforts of Brooklyn congressman Charles B. Law, who later drowned in mysterious circumstances (though not in Jamaica Bay, however shallow). But keeping these lanes open was itself a Sisyphean task, labor quickly undone by powerful currents. Rockaway Inlet, the very gateway to the future seaport, was described in 1910 as “a shallow strait with a sandy bottom, which under the suction of the tides and the pounding of the surf shifts about in a most treacherous manner.” The motive power of these waters is well illustrated by the absence of present-day Breezy Point on early maps. Between 1866 and 1911, the western tip of Rockaway Peninsula grew by more than a mile; nearly all of today’s Breezy Point community, so devastated by Hurricane Sandy, was ocean before the Civil War. And even if the hydraulics of Jamaica Bay could be made to work, there was the matter of access. Despite the rapid expansion of the city toward its shores after 1900, the bay was still a long haul from the center of life and commerce in New York. More so than Manhattan, this part of Brooklyn was long hampered by problems of transportation that the Coney Island and Flushing canals would do little to remedy. In focusing so much on canals, seaport advocates cast their lot with a technology rapidly approaching obsolescence by the 1920s. The Erie Canal might have been the carotid artery of antebellum America, but it could never match the speed and flexibility of trains or the vast extent of the North American rail network. A seamless connection to the nation’s rail grid was increasingly essential to the port’s success, and this put Brooklyn at an even greater disadvantage than water-girdled Manhattan. The great trunk railroads might lie like bundled nerve endings beyond Gotham’s grasp across the Hudson, but what was far from Manhattan was doubly so from southern Brooklyn. Of course, Brooklyn was not without railroads of its own, but they were internal lines or routes out to Long Island. It was not until 1917 that the New York Connecting Railroad hooked Brooklyn up to the nation beyond, albeit by a long, circuitous route over Hell Gate Bridge and Spuyten Duyvil.24

However roundabout, the Connecting Railroad watered many a garden of dreams. John B. Creighton of the Brooklyn League, well aware of the borough’s “insular position,” was convinced the new line would make Brooklyn “one of the greatest, if not the greatest, manufacturing centre in the United States.”25 A decade later, John Henry Ward proposed a great Union Railroad Terminal at Jamaica Bay served by the Connecting Railroad. Described as “an inland station of huge dimensions,” it would bring together “all the great trunk lines of the Metropolis” via a short spur of the Long Island Rail Road that ran from the Connecting Railroad in East New York to Canarsie Pier—the old Brooklyn and Rockaway Beach line. Ward’s scheme, published in September 1919, was the most sophisticated treatise yet on the actual infrastructure needed to make the deepwater port work. Ward was a waterfront development specialist with an office in the old New York Times Building on Park Row and a founding member of the Citizen’s Budget Committee. His rail terminal, though promised to be “second to none in the universe,” was but a small part of a sprawling complex for ships, trains, and motor trucks he proposed called the Trinity Freight Terminal. This would be the great ganged switchbox powering the Jamaica Bay port, located at the foot of Pennsylvania Avenue, about where the Spring Creek Towers housing estate stands today (formerly Starrett City). Ward was especially interested in the efficient delivery of fresh food and thought it defied logic to serve the city’s millions from so crowded a “kitchen” as lower Manhattan. “How absurd it is,” he wrote, “to so largely feed more than 8,000,000 people of the Metropolitan area from a section that is so inaccessible and remote, and otherwise so cramped and busy . . . as the section below Canal Street.” Indeed, to Ward, this “inadequacy of the present central wholesale foodstuffs market” was not just contributing to the high cost of city living; it was “the great eruptive volcano of causes thereof.” Ward’s plan called for a dozen “mammoth piers”—450 feet wide and 1,600 feet long—to receive the world’s cargo. It would also feature grain elevators, a Central Wholesale Market, abattoirs, an ice plant, coal storage facilities, a dry dock, and ship repair yards. But Ward’s most innovative idea, decades ahead of its time, was the “Store-Door Service” he proposed using a fleet of “specially designed and standardized” motor trucks to distribute fresh meats and produce to local markets throughout the city. What made Ward’s proposal truly remarkable was the “demountable body” his trucks would be equipped with. Once the truck was fully loaded at the wharf, it would be driven to a rail siding in the terminal, where

a traveling crane takes the full body off the chassis and puts it onto the flat car destined for the railroad divisional freight station within the freight zone in which the foodstuffs are to be delivered. At the Divisional Railroad Freight Station another traveling crane takes the Motor Truck body . . . off the flat car and puts it on another chassis, and it is at once driven to the store of delivery by only a short haul.26

Bronze plaque cast by Paul E. Cabaret and Company for presentation to Congressman Charles B. Law, 1910. The erstwhile “Champion of Jamaica Bay Harbor” drowned in Lake George. Henry Meyer Collection, Othmar Library, Brooklyn Historical Society.

This may sound familiar, for it’s the first proposal for modern intermodal containerized shipping, an idea that would revolutionize world commerce by replacing the costly and inefficient “break-bulk” method of schlepping goods between sea and land. Had this one idea of his been adopted, John Henry Ward would have become a very wealthy man. But he buried his “demountable body” stratagem within an otherwise grandiose and unrealistic scheme that was doomed to fail—the puny Connecting Railroad could never have served a world-class seaport; it would have been like using a dime-store extension cord to power a sawmill. The global economy would have to wait some forty more years for containerization to finally make its debut, this time at the hands of a North Carolina entrepreneur named Malcolm Purcell McLean, founder of the mighty Sea-Land shipping line.

In the end, a plan is only as good as the assumptions it is built upon; and those on which the Jamaica Bay dream were based began to vaporize like mist on the morning water. New York in the 1920s might have had the industrial output of Chicago, Cleveland, St. Louis, and Philadelphia combined, but it was not the city’s destiny to remain a mighty manufacturing center. Gotham’s age of grease and muscle and working waterfronts faded in the decades after World War II, as the city gradually reinvented itself as a global city dominated by a range of service-sector industries—information technology, banking and finance, education, media, marketing, and publishing—whose raw materials were knowledge and information instead of lumber, coal, or steel. Few indeed in the Roaring Twenties could have anticipated a day when the West Side’s swarming wharves would lie idle and rotting, as many were by the 1970s. Today, with the city bustling with creative-class strivers and globe-trotting elites, New York’s once-neglected waterfront—from the Chelsea Piers to Brooklyn Bridge Park—has been revived and renewed. Waterfront real estate is now so dear it seems almost inconceivable that it was once used for anything other than upscale condominiums and high-style parks.

There is, of course, still commercial port activity in New York City today—at Red Hook and Sunset Park, and on Staten Island at the Howland Hook Marine Terminal—but the vast majority of port functions long ago migrated to New Jersey, whose mainland perch gave it a tremendous competitive edge over New York. It was far easier to dredge the Newark meadowlands into a deepwater port, after all, than to extend the nation’s trunk railroads across two rivers and all of Brooklyn. That New Jersey would one day muscle in on Gotham’s trade was something New Yorkers had fretted over since colonial days. In his 1687 report to London, Governor Thomas Dongan complained that reprobate ship captains were running goods to the Jersey shore to avoid paying customs in New York. “Wee are like to bee deserted,” he warned, “by a great many of our merchants whoe intend to settle there.” His delightful solution? Make “East and West Jersey” part of New York! “To bee short, there is an absolute necessity those provinces and that of Connecticut be annexed.” Two centuries later, shippers began migrating across the Hudson to avoid the booming, overcrowded port. In 1908 John Creighton reported that some thirty firms had recently decamped to Newark, “where they can have direct connections with the great trunk line railroads.” Harold A. Caparn, in a park proposal for Jamaica Bay’s islands, acknowledged that a harbor there would succeed only in the absence of competition from New Jersey. Jamaica Bay might be “eight or ten miles nearer Europe,” he noted, but the Newark marshes “could be dredged and filled in the same way and for the same purpose.” And unlike isolated Jamaica Bay, a port at Newark would be “on the mainland and in direct communication with all the lines of railroad.”27

It was on April 30, 1921, that fate threw its weight toward the Garden State. On that day, a compact was signed establishing the Port of New York Authority, the self-supporting public agency known today as the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. The Port Authority formally sanctioned a long-standing fact—that competition for shipping between New York and New Jersey was wasteful and inefficient, and that the entire region would be better served if its shared waters were managed as a single port. Port Newark, first excavated in 1910, was modernized by the Port Authority after World War II and eventually expanded into today’s Port Newark–Elizabeth Marine Terminal. It was here that the first shipment of standardized containers was made in 1956, and—two years later—the world’s first container terminal opened by Sea-Land. Port Newark–Elizabeth is today the largest port complex on the Eastern Seaboard and was for a time in the 1980s the busiest container port in the world (the spectacular rise of China has since moved Hong Kong to the head of the pack). But big plans generate tremendous momentum and, like a loaded freight train, tend to roll on long after the brakes are applied. Despite the great shift of port activity to New Jersey, dreams lingered on for years at Jamaica Bay. Only weeks before the Port Authority was formed, the Long Island Daily Press reported that the channel dredging had advanced enough to allow a fleet of ten freighters—“the first in 300 years, it is said”—to enter the bay, “irrefutable proof that ocean going craft can negotiate the present entrance channel in safety.” And later that spring, June 6, 1921, came the long-overdue and now futile symbolic launch of the Jamaica Bay port project. The occasion tapped for this largely political show was the start of dredging in Mill Basin—the first of seven great industrial basins planned for the bay’s perimeter. A crowd of several hundred people gathered at Flatbush Avenue and Avenue U to hear speeches by dignitaries including Mayor John F. Hylan, Brooklyn borough president Edward J. Riegelmann, and the youthful president of the New York City Board of Aldermen, Fiorello H. La Guardia. As Mayor Hylan approached the podium, the forty-man Department of Street Cleaning Band—resplendent in starched white—struck up “Yankee Doodle.” “The work started today,” he proclaimed, “will progress rapidly and will stop only when the Jamaica Bay project is completed.” La Guardia praised Jamaica Bay as a “natural harbor” and predicted that its metamorphosis would endow New York with “the greatest port in the world,” lamenting only that “it was too long in reaching this day, far too long.” When the speeches were over, the fourteen-year-old daughter of the city’s commissioner of docks, Murray Hulbert, pressed a button that set off a ship’s cannon. As the great boom echoed across the water, “an ungainly dredge boat moved from the shore out into the narrow channel,” reported the Brooklyn Daily Eagle; “Its chains began to rattle and the long-planned, long-discussed, long-delayed Jamaica Bay project was actually under way.”28

Construction of Mill Basin at Avenue U, 1922, the only part of the Jamaica Bay World Harbor to be built. Photograph by Eugene L. Armbruster. Irma and Paul Milstein Division of United States History, Local History and Genealogy, The New York Public Library.

The author and his brother Richard at construction site of Kings Plaza Mall, Flatbush Avenue and Avenue U, 1971. The site is still zoned for heavy industry, a legacy of the failed port project. Photograph by Rose Campanella, Collection of the author.