CHAPTER 15

THE BABYLONISH

BRICK KILN

Let us open new streets, clean up the populous neighborhoods that lack air and daylight, and let the sun’s beneficial rays penetrate everywhere . . . like the light of truth in our hearts.

—NAPOLEON III

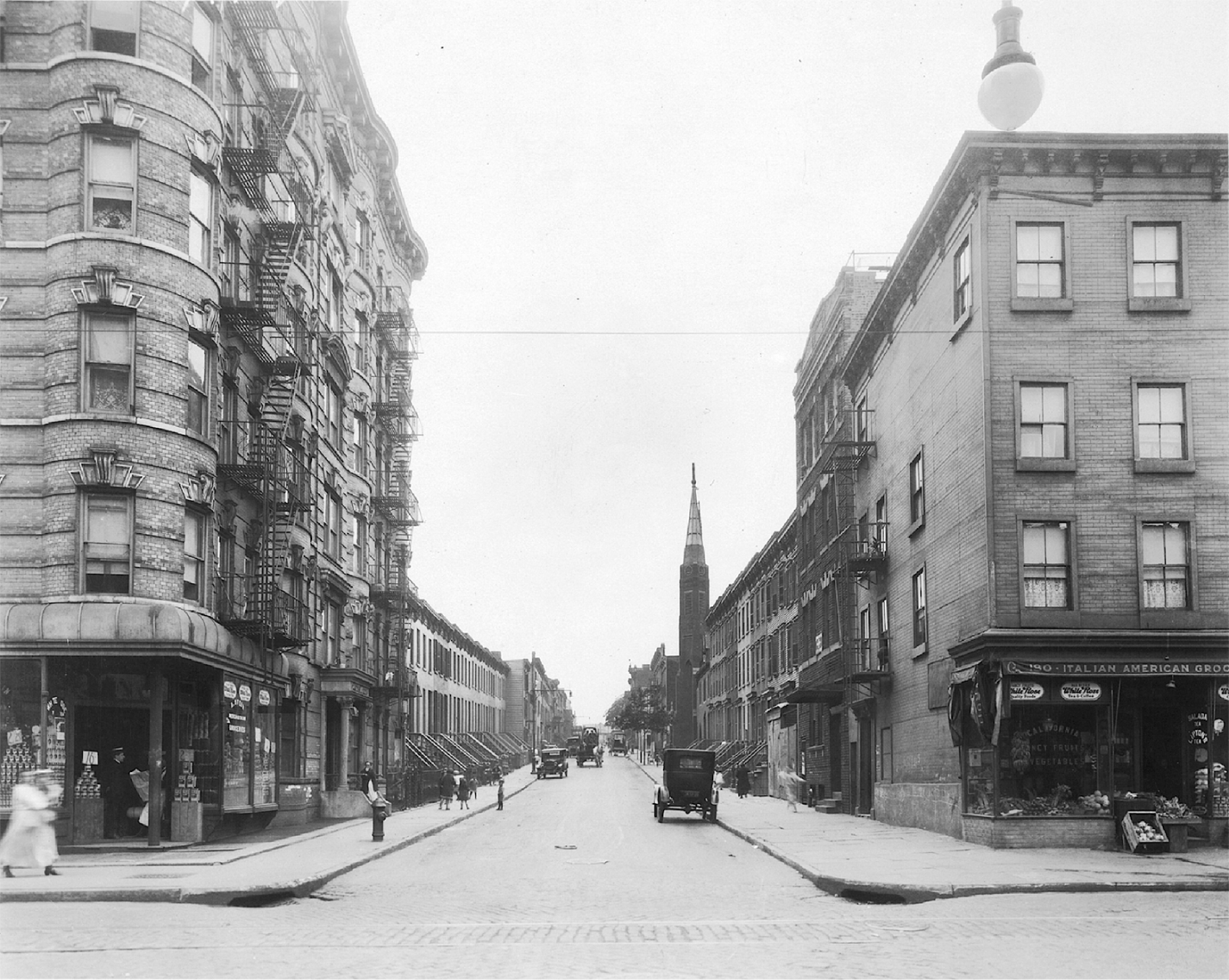

A stone’s throw from the star-crossed civic center, just south and west of the Brooklyn Navy Yard, were some of the worst slums in all of Gotham—the embattled old Fifth, Eleventh, and Twentieth wards. Life in this vast human rookery, with its tenement-packed streets and cold-water flats, was only a nick better than what Jacob Riis had documented a generation earlier on the Lower East Side. Just below the Navy Yard, from Prince Street east to Carlton Avenue, was a predominantly African American slum known as the “Jungle.” Nearly 83 percent of the residential buildings here lacked either central heat or hot water in 1940; well over a hundred had only hall toilets, and some still used century-old outhouses. The area was riven with disease, and scored the highest rates of tuberculosis and infant mortality in the entire city. Life was even harder in the nearby Fifth Ward, where residents lived cheek by jowl with heavy industry that spewed untold toxins into soil, air, and water. The 1939 Federal Writers’ Project guidebook to New York City called the Fifth Ward “a shapeless grotesque neighborhood, its grimy cobblestone thoroughfares filled with flophouses, crumbling tenements and greasy restaurants.” It was haunted, too, by war crimes and death; for in 1808 a mass grave was found on the west shore of Wallabout Bay containing the remains of some ten thousand Americans who had perished aboard British prison ships during the Revolution. The remains were interred in a crypt—a wall of which was discovered in 2003 at 91 Hudson Avenue—and later moved to the Prison Ship Martyrs’ Monument atop Fort Greene Park.1

Lost world: High Street looking west from Hudson Avenue, 1926, heart of Brooklyn’s vital, embattled Fifth Ward. Everything in this view will eventually be razed for the Farragut Houses. Brown Brothers photograph. Irma and Paul Milstein Division of United States History, Local History and Genealogy, The New York Public Library.

The building stock in the Fifth Ward was among the oldest in Brooklyn, erected between 1818 and the 1830s by speculative builders who filled the marshy western shore of Wallabout Bay to erect sturdy brick Greek revival shop houses. It became known as Vinegar Hill, after a battle site of the Irish Rebellion of 1798, though most people knew the area as “Irishtown.” The spiritual centerpiece of the community was St. Ann’s Church, at the corner of Front and Gold Streets, sadly razed in 1992 for a parking lot. A modest Gothic structure, it was designed by Patrick C. Keely, an Irish-born architect and neighborhood resident who built some seven hundred churches for working-class parishes up and down the Eastern Seaboard—from St., Joseph Church in New Orleans to Boston’s colossal Cathedral of the Holy Cross, still the largest Catholic church in New England. After the Civil War, industry began moving into the area, pushing more affluent residents south to newer neighborhoods and leaving behind the very poor. The streets in and around Hudson Avenue became crammed with a hodgepodge of shops, factories, and slaughterhouses. Storage tanks filled with explosive gas rose alongside crowded tenements. It was an urban planner’s nightmare and explains why exclusionary zoning was taken up with such zeal by Progressive Era reformers—something we often forget when we wax rhapsodic on the mixed-use urbanism of prewar America. Vinegar Hill was soon a mob-ruled slum, filled with “ricketty, tumble down houses,” noted a journalist in 1873, “and hordes of ragged, unkempt children.”2 It was especially notorious for its gin mills and distilleries. Bootleggers employed gangs of local youths to chase government inspectors off the streets. Even the police dared not enter the area.

Matters reached a breaking point in the fall of 1870, when two thousand federal troops were dispatched from the Navy Yard to administer a dose of law and order. Bedlam ensued, and “for quite a while,” reported the Times, “a lively time was made by showers of stones and brickbats flying through the air. Every chimney and window seemed to have an enraged distiller behind it, who felt it to be his duty to break the head of at least one soldier.” When the commanding officer ordered his men to load their rifles, “the belligerents became like lambs, a little swearing excepted.” Mash tubs, vats, and stills were smashed and overturned by the troops, who nonetheless made sure to set aside thirty barrels of rotgut whiskey for their troubles.3 In time the Fifth Ward Irish gave way to immigrant Italians from the Lower East Side, while a small community of African Americans, established before the Civil War, held its ground on lower Sands Street. It was no paradise of brotherhood. Irish toughs like Jimmy Maroney’s River Front Gang battled equally vicious Italian bands for control of neighborhood turf. The very future of that turf itself was tenuous. Rumors had swirled for years that a sister span to the Williamsburg Bridge would annihilate the district. The fears were not unfounded. The East River Bridge Company had indeed been granted a charter in 1892 to take Hudson Avenue over the East River to Grand Street in Manhattan. As explained in an 1893 Harper’s Weekly article, the Hudson Avenue Bridge would have a clear span of 1,470 feet, with piers between Hudson Avenue and Gold Street in Brooklyn and an entrance at the junction of Myrtle and Hudson avenues. In Manhattan, the bridge would set down in the vicinity of Jackson and Scammel streets (site of the Vladeck Houses today) and run north into Grand Street. Though the company later lost its charter, the specter of a bridge continued to loom over the ward like a sword of Damocles. As late as March 1901, bids were solicited for construction of a tower in Brooklyn to take “bridge No. 3 . . . from Pike Slip, Manhattan, to Hudson Avenue.”4 Residents of the besieged district finally breathed a sigh of relief when the crossing was sited instead at the foot of Adams Street, for what would become the Manhattan Bridge.

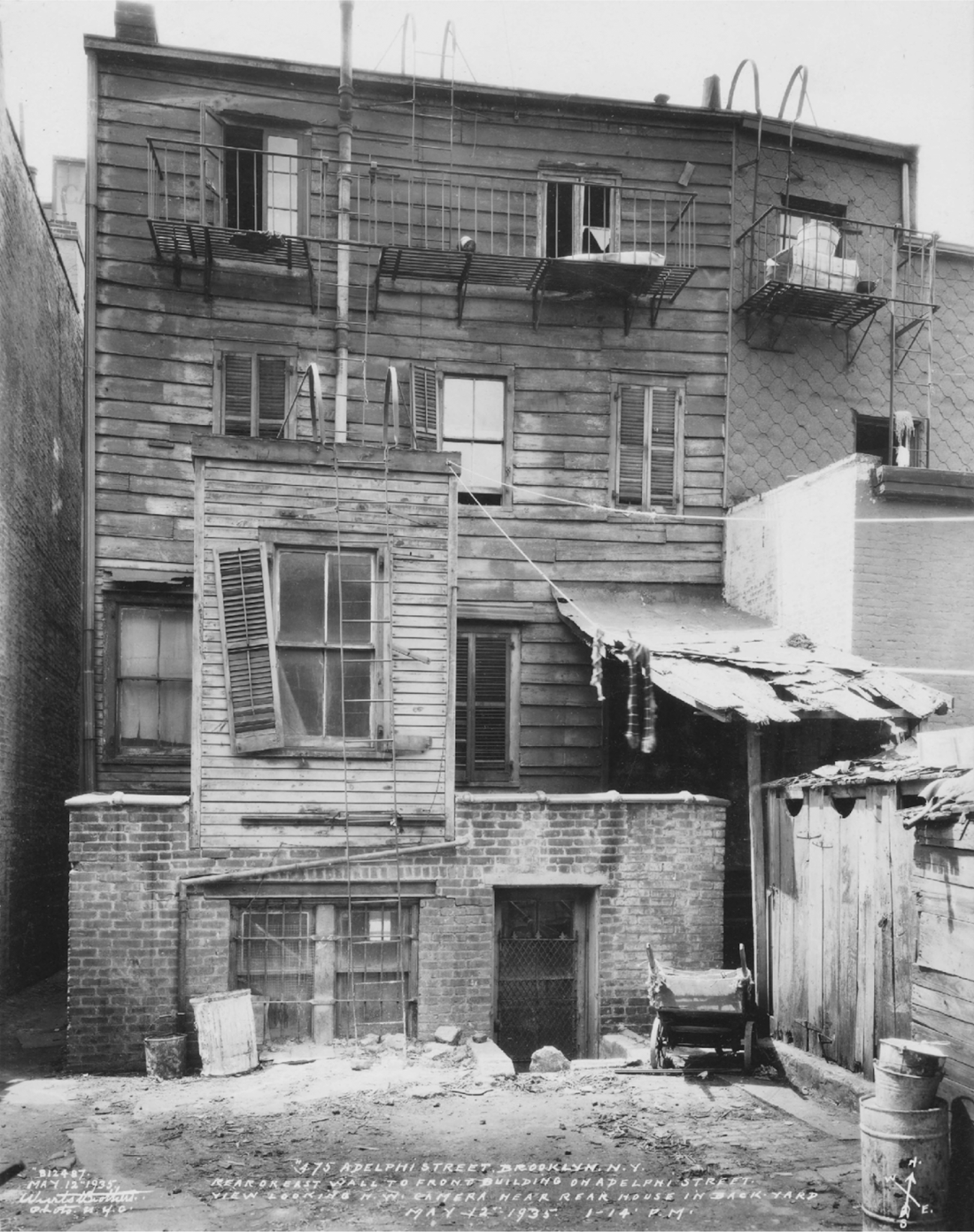

Tenement at 475 Adelphi Street. Irma and Paul Milstein Division of United States History, Local History and Genealogy, The New York Public Library.

Threats came in smaller packages, too, from the legions of rats that swarmed up from the East River at night to diseases long eradicated from the rest of the city. In February 1893, an outbreak of typhus was reported at 31 Front Street—a building “peopled by many Italians of the lower order,” grumbled the Eagle, “who do not know enough to keep themselves and their surroundings clean.” Smallpox outbreaks bedeviled the Navy Yard slums as late as 1902. A decade later, Elizabeth Venable Gaines—a progressive educator at Adelphi College (then still in Clinton Hill)—found that nineteen children had perished on a single street in the Italian ghetto west of the Navy Yard; forty-two others had been blinded, and eighty-nine crippled by disease. This was a place, it seemed, “where babies seemed to be born only to die.”5 Even for adults, life in the Fifth Ward was not easy. Livestock unloaded on the wharves each week were driven bleating and lowing up Hudson Avenue to slaughterhouses at Tillary Street, where the terror-screams of animals created many a vegetarian. Paint, soap, lead, and leather works spewed poison into soil and air. Towering over everything were the four chimneys of Brooklyn Edison’s Hudson Avenue station, the largest steam turbine generating plant in the world. Completed in 1927 with a capacity of one million horsepower, it electrified the vast tide of residential development unleashed across Brooklyn and Queens in the Jazz Age. The plant also delivered steam to hundreds of office buildings in lower Manhattan, making vapor-exhaling manhole covers a new part of the Gotham winterscape. It brought no such magic to the streets of the Fifth Ward. When workers purged the boilers, a great drift of ash would fall silently over the neighborhoods beneath its four-hundred-foot smokestacks. Mothers would shout across the backyard lots, “Pull in the wash!” while children donned folded newsprint hats and listened as the cinders tinkled down upon their paper trilbies—black snow from the titanic God of Light.

Long before Dumbo; looking west over the Fifth Ward, April 1946. The Brooklyn Navy Yard and Hudson Avenue Generating Station are at right. New York City Housing Authority, La Guardia and Wagner Archives.

To many reformers, the foulest toxin in these parts came not from industry but from the merchants of pleasure and flesh on Sands Street, a gritty gauntlet that ran from the main gate of the Navy Yard to Washington Street. It bore the name of the brothers who first platted this part of Brooklyn for development, Comfort and Joshua Sands. Natives of Cow Neck, Long Island (Sands Point today), the pair made a dubious fortune selling overpriced provisions to the Continental Army during the Revolution. After the war, Comfort founded the Bank of New York with Alexander Hamilton, becoming its first director in 1784. That year he and Joshua acquired part of the old Rapelje spread west of Wallabout Bay, where they launched a speculative venture named City of Olympia. They hoped to make its hilly prospect a retreat for harried New Yorkers. Instead, Connecticut Yankees from New London came, seeking to establish a shipworks on the bay. The Sands brothers themselves erected warehouses, wharves, and ropewalks to manufacture rigging, laying the groundwork for what would eventually become the largest military shipyard in North America. In the years before the Brooklyn Bridge, Sands Street was a fashionable address—many of Brooklyn’s “first families” made it home, worshipping at the Sands Street Methodist Episcopal Church, among the city’s oldest and most prestigious houses of worship. The street turned to commerce with the advent of horsecar service between Fulton Ferry and the Navy Yard gate—then on York Street—a transition accelerated by the opening of the Brooklyn Bridge in 1883. Now Sands Street was the most direct route between the Navy Yard and Manhattan. What sealed its commercial fate was the July 1896 opening of a Sands Street entrance to the Navy Yard, a move prompted by completion of the elevated rail depot at Washington Street. Overnight, Sands Street became a passageway to the city for thousands of sailors on shore leave from the Navy Yard, a street they had to traverse the length of on their way to and from downtown and the trains to Manhattan or Coney Island. Merchants responded nimbly to this new source of steady custom. Naval outfitters opened there, as did luncheonettes and shops that cleaned and tailored uniforms or rented civilian clothes to “jackies” who wished to roam the city less conspicuously. Pawnbrokers lent hard up sailors cash; souvenir shops and photographic galleries provided keepsakes for loved ones back home. When the fleet was in, Sands Street was transformed; “all you could see,” one merchant recalled, “was a sea of white hats.”6

Brooklyn Edison’s Hudson Avenue Generating Station, June 1932. Photograph by Fairchild Aerial Surveys, Inc. Collection of the author.

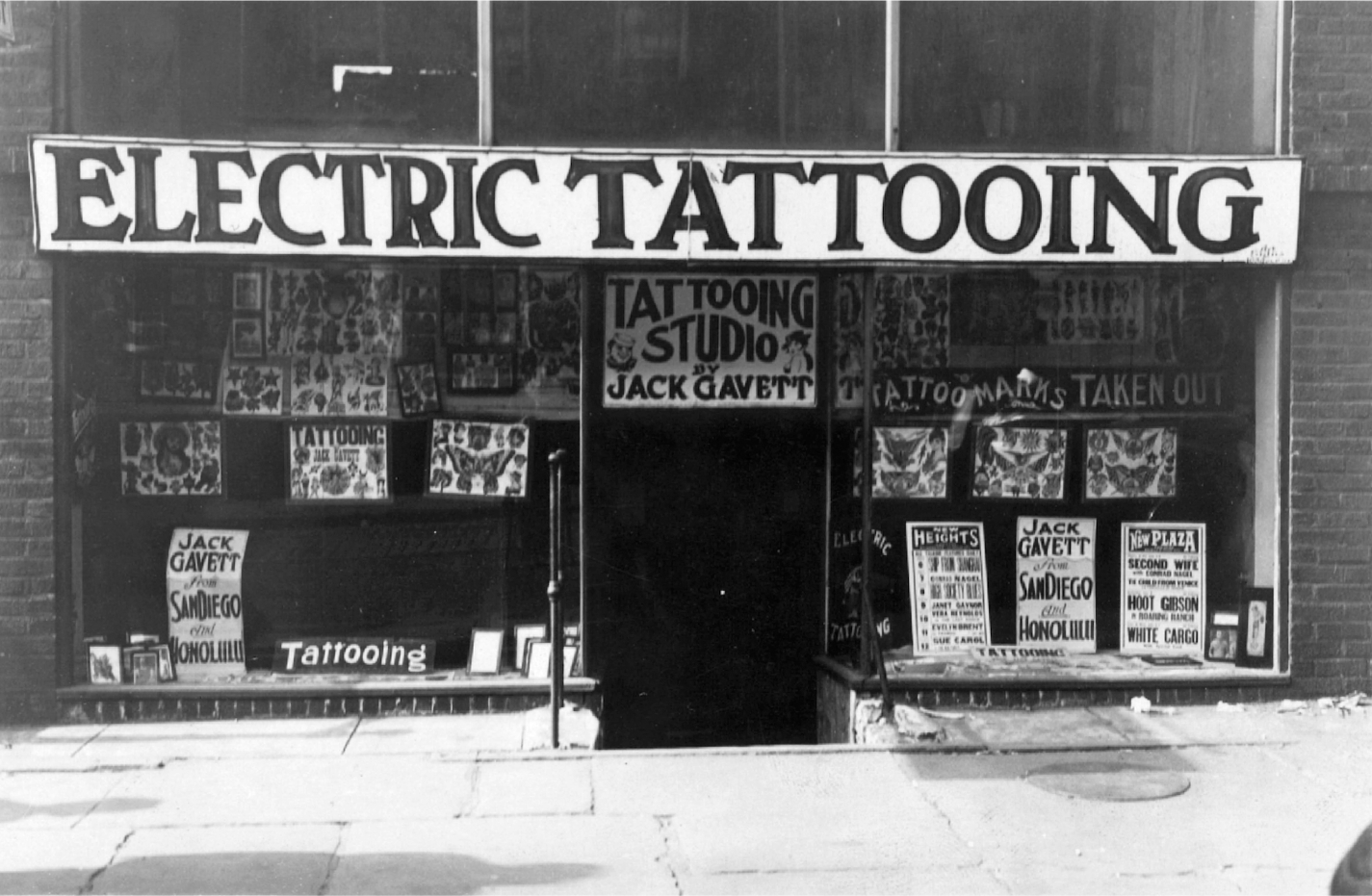

Shore-leave sailors supplied only part of the trade that sustained Sands Street a century ago—at least by day. It was also a vital shopping street for residents of the increasingly polyglot neighborhoods around the Navy Yard. A 1908 survey found four Italian doctors and an equal number of Italian barbers on Sands Street. There were German butchers and Jewish tailors, shops catering to the area’s large Polish and Lithuanian populations, and an Irish-owned bar on almost every street corner. Immigrants had long flocked to the area for cheap housing and industrial jobs; others came by way of the military installation at its doorstep. The rise of America’s blue-water navy at the end of the nineteenth century made the Navy Yard an unintended agent of diversity. A tiny Chinese community—mostly waiters and their families—was centered on the Chinese Association on nearby Bridge Street. A substantial Filipino community flourished closer to Washington Street, seeded by a discriminatory section in the immigration law that barred citizenship to any Filipino except those honorably discharged from the US Navy. Sands Street was soon the main drag of Filipino Brooklyn, “dotted with little restaurants whose walls are painted with gay parrots and scenes from the islands.” Small but tenacious, the community held on in the face of urban renewal until its spiritual center—a Roman Catholic church at 209 Concord Street—was demolished for the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway. A small Japanese settlement was established even earlier in and around Sands Street by cooks, valets, and servants of Pacific fleet officers. The community doubled almost overnight when the navy forcibly discharged all Japanese enlisted men as “yellow peril” fears erupted after Japan’s victory in the Russo-Japanese War—the first time an Asian nation had defeated a Western power. By 1910 there were several Japanese boardinghouses on Sands Street, two restaurants, and bakeries where “dainty rice and tea cakes” were manufactured, delighted an Eagle reporter, “in full view of the street.” There was also a Japanese soda shop and candy store, a curio shop, and a purveyor of artificial flowers. A Japanese physician had offices on High Street, and a tattoo artist “of no mean ability” plied his trade nearby.7

Hudson Avenue looking north toward the Boorum and Pease factory (extant), c. 1946. The older buildings here, which included the grocery store and home of the author’s grandparents at 96 Hudson Avenue, were demolished in the early 1960s for P.S. 307. Photograph by John Tambasco.

But there was a darker side to this corridor of noonday commerce. Shopkeepers were squeezed by organized crime and lived in fear of holdups.8 As twilight descended, the busy thoroughfare became “a dark and almost sinister street”—a rogue’s gallery of establishments aimed at the wallets and loins of seamen. There were basement gambling dens, porn shops, brothels male and female, and bars galore—Leo’s, Richard’s, Tony’s Square, Terry Mitchell’s. Bar brawls, scuffles, and stabbings were a nightly ritual on Sands Street. Drugs were a problem as early as 1906, when it was revealed that Sands Street pharmacists were selling cocaine even to youths. Coke may have been addictive, but the “whiskey” sold to sailors—especially during Prohibition—was often pure poison. In a single week in December 1921, scores of men were sickened by toxic hooch they bought from local bootleggers. Many awakened hours later, only to find they had been relieved of all their valuables. One man—a fireman on the USS Pueblo—died from acute alcohol poisoning, prompting the navy to join police, federal agents, and staff from the Sands Street YMCA to crack down on the lawbreakers. More than anything, however, Sands Street was about sex, in all its forms and variations. Prostitution was right behind keel laying and booze as a force in the local economy, though many women dismissed as whores were probably no more than maritime groupies—“silly girls who follow the navy from port to port” (mostly “from Pennsylvania,” offered the Eagle, without evidence), who rented rooms in and around Sands Street and would “stay until the sailors depart and then head for the next stop of the fleet.”9

Campaigns by church and state to combat strumpetry were checked only by the fear that, absent whores to slake their lust, horny sailors would simply start humping each other—as they most surely did. Cruising was as much a part of Sands Street life as the all-night coffee pot. An antivice society investigator in 1917 found Sands Street on a summer night filled with “sex mad” sailors, many of whom “were with other men walking arm in arm,” and even kissing. Poet Hart Crane was among the many young men from all classes and quarters of the city who came to Sands Street in search of sexual pleasure, a place he could find lovers far from his circle of Gotham literati—“among men that his friends would never meet.” It was a dangerous sport for Crane, and “more than once,” writes Evan Hughes, “he came home beaten and bloodied.”10 Gay men were not the only ones who came to savor Sands Street’s forbidden fruits. As early as the 1930s, the street had begun to attract tourists, some comparing the “picturesque Brooklyn thoroughfare” to bohemian Greenwich Village. Well-dressed men and women, university cads down from New Haven or Ithaca would “roll down Sands St. in luxurious automobiles,” seeking adventure and titillation. By this time, the street was a mere shadow of its truly wild days during Prohibition or World War I; one writer even went so far as to call it “as tame as Flatbush.” The 1939 publication of a Federal Writers’ Project guide to New York City further increased the number of young people coming to Sands Street in search of authenticity and ashcan grit.11

One of these slum tourists was Carson McCullers. In 1940, the Georgia-born writer moved into a townhouse at 7 Middagh Street that Harper’s Bazaar editor George Davis had bought to fill with an ersatz family. Between 1940 and 1942 an extraordinary group of artistic and literary souls gathered under its roof—Benjamin Britten, Gypsy Rose Lee, poets W. H. Auden and Chester Kallman, Paul and Jane Bowles, set designer Oliver Smith, even Thomas Mann’s son, Klaus. This “rambling society of creative eccentrics,” as Caroline Seebohm called them, seemed ordered just the way “the populace once liked to think of artists,” observed British poet and playwright Louis MacNeice, then a lecturer at Cornell, “ever so bohemian, raiding the icebox at midnight and eating the cat food by mistake.”12 Anaïs Nin called it February House. Anticipating today’s authenticity-seeking hipsters by half a century, McCullers and her housemates would often head to Sands Street after a late, long meal—“a little area as vivacious as a country fair” where the liquor was cheap and “sunburned sailors swagger up and down the sidewalks with their girls.” She, of all the Middagh Street crowd, was especially moved by this boulevard of the id and its flamboyant characters. “Some of the women you find there are vivid old dowagers,” she wrote in The Mortgaged Heart (1955), “who have such names as The Duchess or Submarine Mary.”

Jack Gavett’s tattoo parlor, 59 Sands Street, July 1930. Photograph by Percy Loomis Sperr. Irma and Paul Milstein Division of United States History, Local History and Genealogy, The New York Public Library.

Every tooth in Submarine Mary’s head is made of solid gold—and her smile is rich-looking and satisfied. She and the rest of these old habitués are greatly respected. They have a stable list of sailor pals and are known from Buenos Aires to Zanzibar. They are conscious of their fame and don’t bother to dance or flirt like the younger girls, but sit comfortably in the centre of the room with their knitting, keeping a sharp eye on all that goes on.

In one bar McCullers was mesmerized by “a little hunchback who struts in proudly every evening, and is petted by everyone,” a character who appears in slightly altered form as Cousin Lymon in McCullers’s 1951 masterpiece, The Ballad of the Sad Café. Sands Street and its tumbledown quarter of cobblestoned blocks running to the East River may have even been the inspiration for West Side Story, at least according to Middagh Street denizen and Broadway producer Oliver Smith. Smith often cruised Sands Street and took late-night walks in the quarter with choreographer Jerome Robbins, and his set design for the original production of the theatrical, he once confessed, “was more Brooklyn than Manhattan.”13

Just five years after Carson McCullers moved to Brooklyn, the whole brave, sad, beautiful urban world west and south of Sands Street and the Navy Yard was—for better or worse—swept into oblivion. The wheels of annihilation were officially set into motion on Thursday, June 27, 1940, a day before city schools closed for the summer. That morning, Mayor La Guardia and Brooklyn borough president John Cashmore met in the Park Avenue apartment of Governor Herbert, H. Lehman to see him sign a $20 million state loan to the city for a vast public housing complex, one that would replace “the man-made jungle of the Navy Yard slums . . . one of the worst blighted sections in the entire city” with an austere array of high-rise towers set amidst a field of landscaped lawns. Contracts were let to level the thirty-nine-acre site. All that summer and fall the city worked feverishly to move some sixteen hundred families out of the condemned tenements, shacks, and boardinghouses. Most were rehoused within a four-mile radius of the site—temporarily, at least; they, along with defense workers and navy personnel, would have priority access to a new apartment on the site. The handful of families resisting eviction eventually yielded to “a touch of diplomacy here and a bit of sympathy there,” obviating the need for ugly forced removals. Many residents had lived in their homes for decades, and—slum or not—were heartbroken to leave. An elderly barber named Frank Scania had cut hair at 44 Ashland Place for forty-five years, paying the same $13 rent he was charged in 1895; dazed by his impending ouster, Scania lingered until the end, the last holdout in a building erected when Andrew Jackson was president.14

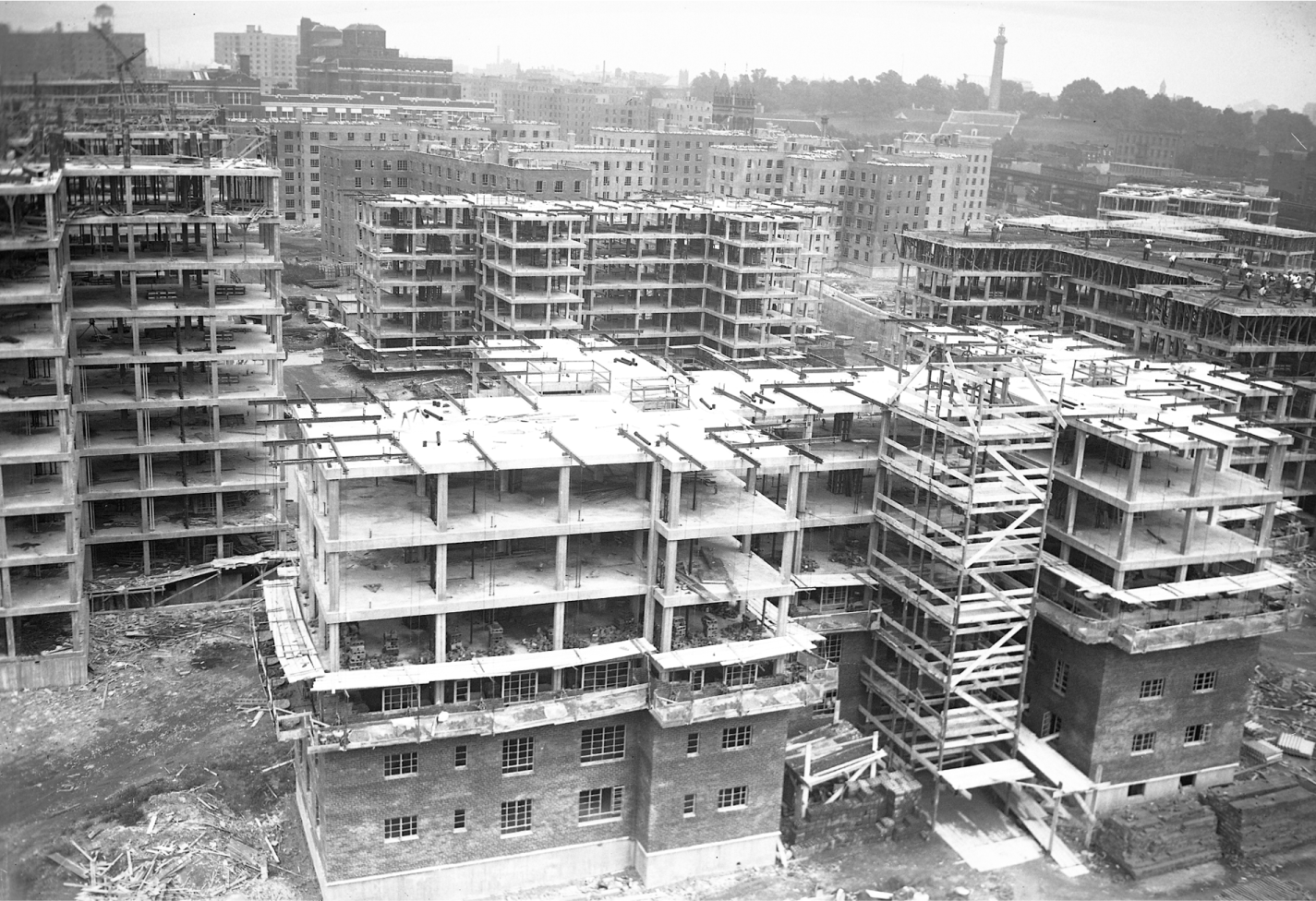

As the people moved out, squads of Pied Pipers moved in to deal with residents of a different sort. Razing nearly forty acres of tumbledown shacks and tenements would unleash a biblical plague of vermin. Crack exterminators were called on to kill the legions of rats before they could infest neighboring areas. “As fast as a house is vacated,” related the Eagle, “the drab angels of death move in.” Tasty morsels of meat and fish were left behind, loaded with a toxin made from the ground bulbs of sea onion. How many rats were dispatched is unknown, but extermination work for the smaller Baxter Terrace housing project in Newark killed 500,000 rodents. Demolition began in December, and by early March 1941 more than half of the site’s seven hundred-odd structures were gone. Ground was broken on May 6 for the project’s pilot phase at Park and North Portland avenues. With customary bluster, Mayor La Guardia hailed the start of the largest low-rent housing project “ever attempted in this or any other country.” Invoking the Navy Yard next door, Governor Lehman spoke of good housing as vital to American security; for “housing projects to protect us from the enemy from within,” he remarked, “were as essential as battle-ships to protect us from the enemy from without.” Brooklyn borough president John Cashmore likened the project to “the kind of war we like to fight, a war against filth, crime and disease.” With a crowd of two thousand looking on, Lehman climbed into the cab of a steam shovel, shifted a lever, and dug its bucket into the terra firma. Aided by “quick-setting cement and floodlights for night work,” the thirteen-story building went up fast—too fast, as we will see. The first apartments were ready for occupancy by November, months ahead of schedule.15

Men drinking in rear of tenement house at 293 Hudson Avenue, April 1940, one of hundreds of substandard buildings that would soon be cleared for the Fort Greene Houses. New York City Housing Authority, La Guardia and Wagner Archives.

By this time the rest of the huge project was well under way. Commissions for the thirty-five towers, divided into three “units,” went to some of the city’s most prominent architects. Wallace K. Harrison and J. André Fouilhoux were lead architects for the first set of buildings. The men had been part of the Rockefeller Center design team and collaborated on the Trylon and Perisphere, centerpiece of the 1939 New York World’s Fair; Harrison would go on to play a formative role in the creation of the United Nations Headquarters. Their associates on the Fort Greene job were Rosario Candela, master craftsman of the Park Avenue apartment, and Albert Mayer, an architect-engineer who helped found the Housing Study Guild and whose service in India during the war would lead to a plum commission: planning a new capital city for the Punjab at Chandigarh. It was only after Mayer backed out of this project—his partner, Matthew Nowicki, had been killed in a plane crash—that the Chandigarh job was handed to Le Corbusier, who retained much of Mayer’s street grid. Ely Jacques Kahn, designer of some of Manhattan’s most prestigious department stores, led the team for the second unit of the Fort Greene Houses, while housing reformer and regional planner Clarence S. Stein headed the third. Stein, the most progressive of the group, had been part of a brilliant gathering of New York intellectuals in the 1920s that sought to realize in America the ideals of English town planners and social visionaries Ebenezer Howard and Patrick Geddes. In 1923 he helped found, with Lewis Mumford and Benton MacKaye, the Regional Planning Association of America, and went on to design several landmark communities: Sunnyside Gardens and the Phipps Garden Apartments in Queens, and the celebrated “town for the motor age” at Radburn, New Jersey, meant to be America’s first true Garden City.

By almost every measure, the scale of the Fort Greene Houses was vast. This was public housing on the order of the Manhattan Project, the single largest such development ever attempted in the United States. Some six thousand tons of steel went into framing its buildings, nearly the amount used to erect the Eiffel Tower. There were fifty thousand windows and twenty thousand doors in the complex, and its ninety-three elevators boasted a combined lift of nearly a mile. Orders for masonry emptied brickyards from Newburgh to Albany. More than sixteen million bricks were devoured by the project—set end to end, they would form a line from Brooklyn to Mexico City. The surface area of the exterior brick walls alone covered almost two million square feet—more acreage than the site itself. With a projected resident population of over thirteen thousand people, Fort Greene was an instant town, roughly the size of Saratoga Springs, Beacon, or Oneonta at the time. Formal dedication took place in September 1942, with Governor Lehman, Mayor La Guardia, navy admiral E. J. Marquat, and other officials on hand. The ceremonies were broadcast on WNYC.16 It was a historic moment indeed, for the project’s completion marked the arrival of urban design ideology that had been lapping American shores for several years—the tower-in-the-park model that Franco-Swiss modernist Le Corbusier first proposed in the early 1920s. Le Corbusier recoiled at the same conditions of overcrowding and congestion that reformers sought to eliminate in the Fifth Ward. Like many of his generation, he was spellbound by the promise of technology—“the joyous and productive impulse of the new machine-civilisation.” It was that most exhilarating of machine-age innovations—the airplane, and the aerial perspective it enabled—that convinced him of the urgent need to sweep away the calcified urban past. For Le Corbusier, flying over Paris was no joyride but a revelation of human failure; spread out below he saw “a spectacle of collapse” that laid bare a damning fact: “that men have built cities for men, not in order to give them pleasure, to content them, to make them happy, but to make money!” “L’avion accuse,” he declared: “The airplane is an indictment. It indicts the city. It indicts those who control the city.” Here, Corb resolved, was “proof . . . of the rightness of our desire to alter methods of architecture and town-planning.” His mandate rang clear: “Cities, with their misery, must be torn down. They must be largely destroyed and fresh cities built.”17

Fort Greene Houses under construction, August 1942. New York City Housing Authority, La Guardia and Wagner Archives.

It was a seductive call to arms, heeded on both sides of the Atlantic by architects, planners, and developers alike. Traditional forms of urbanism were scrapped almost overnight for a sleek vision of soaring towers in an expansive landscape of parks and motorways. The Fort Greene Houses were a marvel of modernity in the midst of hardscrabble Brooklyn. From atop Fort Greene Park, ramparts aglow in the raking light of a late November afternoon, the Corbusian towers “take on the appearance of a veritable city,” rhapsodized an Eagle reporter. “But it is a city strangely altered from our usual concepts,” he confessed, more like “some strange projection of the future” than anything else in Gotham.18 More perceptive critics saw the folly of imposing a supranational, one-size-fits-all solution on highly specialized urban problems, willfully ignoring the exigencies of local culture, politics, climate, and site. Corb’s machinic urbanism proved antithetical to everything people loved about cities—it was “a frigid megalomaniacally scaled negation,” writes Norma Evenson, “of the familiar urban ambient.”19 The most penetrating critique of this utopianist urbanism on Brooklyn soil came, not surprisingly, from the pen of Lewis Mumford. As skeptical of the machine as Le Corbusier was exhilarated by it, Mumford feared that modernity would release “a Pandora’s box of mechanical marvels that eventually threatened to absorb all human purposes.”20 The title of a 1950 New Yorker essay on the subject—“The Red-Brick Beehives”—says it all. By the time Mumford wrote the piece, a decade after the Fort Greene project broke ground, identical housing estates had popped up all over Gotham. Mumford was troubled by the relentless uniformity of these complexes, as if “arranged by a tidy but too methodical child.” He found this extraordinary given that the projects were designed and built by a diversity of actors—the city housing authority, life insurance companies, private developers. “Strange to say,” he remarked, “dozens of architectural firms, in free rivalry, produced those masterpieces of regimentation,” all seemingly struck from the “same forbidding institutional pattern . . . as if they had all been designed by one mind, carried out by one organization, intended for one class of people, bred like bees to fit into these honeycombs.” Though the projects created housing far superior to the slums they replaced, their sterility and “inhuman scale . . . their barrackslike air” troubled him. These were places formed, he feared, not around family or neighborhood but the elevator shaft. “If this new pattern of building becomes more widely imitated,” he predicted with great prescience, “it will create urban disabilities that will be more difficult to remove than the old slums.”21

With the slums of old long gone from New York City, it is easy to forget just how pernicious an evil unregulated urban density once was to planners and city officials. Today, uncoupled from its toxic former associations, density is cheered as a palliative to ills of a different sort—those born of the placeless sprawl of postwar suburbia and the sterilities of single-use zoning. Open space was desperately needed in the heavily congested neighborhoods around the Navy Yard. But so was housing robust enough to rehouse the thousands of families displaced by slum clearance. Superblock modernism offered a solution to a seemingly unresolvable conundrum: accommodating huge numbers of people while also providing an abundance of open space. The Fort Greene project housed some thirty-five hundred families, more than double the former population on the thirty-nine-acre site. And it did so using a fraction of the land for buildings. Building coverage was over 90 percent in the “Jungle”; the total footprint of the new towers was less than 25 percent. Open space shot from practically zero to nearly thirty acres. It was a victory for all, or so it seemed. For all his qualms about the dehumanizing architecture of the new housing, Mumford—champion of the Garden City—cheered the superblock, calling it “the most important contribution these projects have made to the concept of a new city.” Not only was the superblock economical—eliminating “long stretches of street and with unnecessary duplications of water, sewer, and gas mains”—but it kept vehicular traffic away from the living environment, creating “pools of quiet” that enabled residents to “probably sleep better than the inhabitants of most other parts of the city.” For Mumford, the Corbusian park saved its towers; for without “generous planting of trees, bushes, and flower beds . . . walks and grass plots and outdoor shelters,” buildings like those at Fort Greene justified indeed “Herman Melville’s epithet for New York: a Babylonish brick kiln.”22

Fort Greene Houses nearing completion, 1942. New York City Municipal Archives.

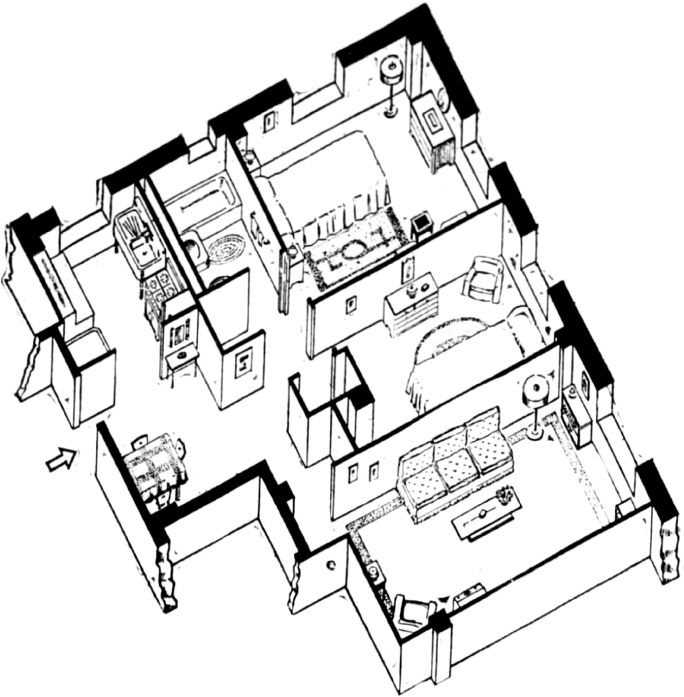

Axonometric rendering of a two-bedroom apartment in the Fort Greene Houses. From Brooklyn Eagle, August 16, 1942.

The opening of the Fort Greene Houses was greeted with a groundswell of enthusiasm by officials, the downtown business community, and the press. To make sure all went well, the city hired an experienced facilities director—an architect named Frank Dorman—to manage the huge estate. Dorman had previously run the Williamsburg Houses and the Vladeck Houses on the Lower East Side. At his side was a large corps of “trained housing assistants,” all women, who would call on tenants “not just to collect the rent, but to discuss with them their problems.” Dorman was confident that he and his handpicked staff of sixty could run the Fort Greene Houses “with efficiency and economy,” making the complex a model for both city and nation. “We won’t have too many problems.” Everyone wanted the project to be a resounding success, a showpiece. “Brooklyn will be proud of this splendid civic achievement,” foretold the Eagle in a sixteen-page Sunday supplement a day before opening on August 17, 1942. It was a Cinderellic metamorphosis indeed: “straggling, sagging rookeries” had been expunged, and in their place was now “comfortable housing for workmen . . . streamlined for happy homemaking.” Few could imagine these gleaming towers as anything but a great boon to Brooklyn. “Borough real estate men,” the paper reported, “are convinced, they say, that property values in the vicinity of the Fort Greene Houses . . . will be favorably affected by the vast residential development.” The well-appointed model unit only confirmed this. Cheerfully didactic, it exuded cleaning-day freshness, vitality, and middle-American values. “In the living room is a divan, two comfortable easy chairs and a chest of drawers,” noted the Eagle, “which serves as both a console table and a place to store household extras. A scatter rug makes a bright spot against the dark gray asphalt tiling of the floor,” while the bed was made up with a “candlewick spread.” The baby’s nursery was airy and sun splashed, with a crib in one corner, “a gay play rug on the floor and a rocking chair for mother.” The apartments all had bathtubs “similar to those in high-rent Forest Hills.” Fulton Street retailers salivated at the throngs of new customers needful of housewares and provisions of every sort. Every major Brooklyn department store ran an advertisement in the Eagle supplement, many featuring handsome white people strolling through the modernist utopia or poring over plans for homemaking. “We salute the exciting development brought by men of vision!” gushed Oppenheim Collins; “We salute our new neighbors who have brought it life and richness!” “We’re anxious to meet you,” chirped Martins, “eager to welcome you as the old friends we hope you soon will be.” “We’re practically next door, you know,” coaxed Abraham and Straus, “just a few minutes away on your bicycle!” Within a decade, no one would be boasting of such proximities.23

Advertisement for Horn and Hardart Automat aimed at residents of the newly opened Fort Greene Houses. From Brooklyn Eagle, August 16, 1942.

Even before the war ended, there were signs that all was not well in this redbrick paradise. The needle barely registered these at first. A beat reporter visiting the Fort Greene Houses just after Thanksgiving 1944 saw that walkways were littered “and windows here and there are broken,” but concluded nonetheless that “time has not dealt too unkindly with the greatest thing of its kind in the city.” But just that summer there had been clashes between black and white youths on the edges of the vast complex. The fighting started, predictably enough, after the sister of one of the ringleaders was catcalled by a group of black teens. A crowd of more than a hundred white youths from the larger neighborhood gathered that night at the Prison Ship Monument before descending on the housing project to exact random retribution. Armed with clubs and baseball bats, the mob “fanned out in all directions, pushing and shoving Negroes in apparent efforts to instigate fights.” Nearly two hundred officers from three precincts responded to the melee. The police were not evenhanded in deploying their nightsticks. The following week, a white Fort Greene resident and community organizer named Belle Sundeen, the office manager of the radical Daily Worker, led a twelve-member, biracial “Anti-Discrimination Committee of Tenants of the Fort Greene Houses” to the Brooklyn district attorney’s office, pressing for an investigation into reports “that police action had been biased and that Negroes had been unfairly treated.”24

Despite this, race relations among residents of the Fort Greene Houses were largely positive—at least at first. Whites dominated the complex when it opened and were still a strong majority in 1945, when only 539 of about 3,500 resident families were African American. This is why all those Fulton Street retailers clamored to advertise in the 1942 Eagle supplement on the Fort Greene Houses: the folks moving in were mostly middle-class families with steady incomes—not welfare recipients, former sharecroppers from the South, or even displaced residents of the impoverished “Jungle” promised new homes. The outbreak of World War II effectively turned the just-launched Fort Greene project into a military housing facility. Priority for units was given to personnel in the Third Naval District and the army’s Second Service Command, headquartered on Governors Island, to women serving with the US Naval Reserve (WAVES), and to workers employed at the Navy Yard and in war-related industry. The change was slow at first, encouraging a too-brief period of seeming harmony and tolerance—a “pleasant neighborliness of races,” as the Eagle put it. “Here Negro and white toddlers eat and play games together and go through all the pre-school and kindergarten learning routines,” a reporter observed of Fort Greene’s on-site nursery school. “When asked to come along to the play corner, a small white girl seized a tiny Negro girl by the hand, in an apparently familiar gesture, and they ran in side by side.” A variety of tenant organizations had turned the forbidding complex into a real community. There was scouting for boys and girls, a group called “Teen Town,” a meeting of men interested in crafts, and support groups for the elderly. At least two outside organizations—the National Negro Congress and American Youth for Democracy—attempted to hold meetings in the project’s recreation room but were stopped by the housing authority because of their links to the Communist Party. Residents even published a monthly newsletter—the Tenant’s Voice.25

But as Fort Greene’s demographics shifted, the fragile ecology of tolerance and goodwill began to fray. The Eagle gamely tried to downplay reports of racial discord, chalking them off as wash-day squabbles common to every American neighborhood. In a painfully forced 1946 piece, columnist Jane Corby insisted that there were “no racial distinctions when it comes to a good, neighborly free-for-all. No racial name-calling. Just clean American fight lingo . . . give and take between racial equals, to be heard up and down any dumbwaiter shaft.” By this time, the navy had moved out nearly all of its three hundred-odd families from the Fort Greene Houses. They were replaced in the main by African American families arriving from North Carolina, Virginia, and other Southern states. As the black population rose, white residents began leaving at a faster clip. Some moved elsewhere in Brooklyn; others headed for the suburbs of Queens, Long Island, or New Jersey. Then came an ill-considered policy directive that virtually assured the end of Fort Greene’s fragile balance of race and class. In January 1947 the housing authority began serving eviction notices to families earning over $3,000 a year. The rule was well-meant—space was needed for the many poor families arriving daily from the South and, increasingly, Puerto Rico and the West Indies. But Fort Greene’s more prosperous families, black and white, were a stabilizing force in the housing complex; purging them was like pulling the keystone out of an arch. By the 1960s, more than fifty families a year were being evicted for exceeding the income cap. “Those are the families we need to keep,” pleaded resident activist Olivette Thompson, “the kind we can’t afford to lose.”26

And so what had been a thriving mixed-race, mixed-income community was transformed almost overnight into a near monoculture of race and class. Housing authority records show that, exclusive of navy personnel, the racial composition of the Fort Greene Houses was 83 percent white and 17 percent black in July 1945. A decade later, the white population was less than 27 percent, while more than 73 percent of residents were either black or Puerto Rican—and many very poor.27 The income cap had another, even more pernicious effect: it punished success. Residents could keep a unit at Fort Greene only if their household income remained below a certain level. To struggle up the economic ladder was to hazard being thrown to a merciless housing market. “The able, rising families are constantly driven out as their incomes cross the ceiling,” noted Harrison E. Salisbury in a 1958 New York Times exposé on the complex drawn from his best-selling book, The Shook-Up Generation. By excluding high achievers and role-model families, the community was deprived of “the normal quota of human talents needed for self-organization, self-discipline and self-improvement.” The rule incentivized inertia, and bent ambition and enterprise toward crime. The result, Salisbury concluded, was “a human catchpool that breeds social ills and requires endless outside assistance.” Equally ill-considered were “senseless man-in-the-house welfare regulations,” as activist Walter Thabit called them—rules that discouraged women from having in their homes an employed, breadwinning male partner. This took a wrecking ball to traditional family structure, laying the groundwork for the single-parent epidemic that would create a generation of black men raised without a male role model. All this worked against the formation of social capital at the Fort Greene Houses, fostering a climate lethal to a sense of community or love of place. It is no wonder, then, that this showpiece of progressive housing policy was soon beset by a shattering gamut of social problems.28

It was during the summer of 1949, with the city besieged for weeks by a terrible heat wave, that crime at the Fort Greene Houses first began making news. On July 11, a delegation of frightened residents led by Fannie Weinstein Bakal, president of the Fort Greene District Civic Association, marched into the Eighty-Eighth Precinct station to beg the police to do something about the escalating number of assaults and burglaries in the complex. Just recently six women had nearly been raped on the grounds, including a grandmother on her way back from the Navy Yard. Bakal led a second delegation to housing authority offices in Manhattan, this time accompanied by five victimized women. A special unit of security guards, she was reminded, had already been deployed at the housing project. But the men were older and poorly trained, and they carried no guns; overwhelmed, they took to patrolling in groups of three. Not a week later two more attempted rapes were reported, including one involving a ten-year-old girl. “Terror stalks the Fort Greene Housing Project these hot, humid nights,” hyperbolized the Eagle, “when fog rolls through the brick canyons from the East River nearby.” Combat veterans from the local post of the American Legion threatened to organize a vigilante committee to fight the crime wave. “I’d just as soon pack a gun myself and guard the place, like we did overseas,” exclaimed the post commander; “It’s come to that.” Faced with a public relations disaster, the Eighty-Eighth Precinct amended its patrol routine to take in the complex; police posts and call boxes were installed at strategic locations. But all this was restricted to the perimeter of the vast housing complex, thanks to the celebrated Corbusian superblock. The police were not permitted to enter housing authority grounds or buildings unless they were responding to a call, or were actively pursuing a suspect. The lack of interior streets kept patrolmen and “prowl cars” on the edges of the vast complex, where their presence had little deterrent effect. The housing authority eventually established an armed force of its own, trained at the city’s police academy, but it took until 1958 for it to open a police precinct within a housing project. They put it, not surprisingly, at Fort Greene.29

By this time, crime was soaring both in and around the huge complex—muggings, burglaries, gang scuffles, sexual assaults all became commonplace. To be out after dark was to hazard life and limb. In October 1953, police just barely headed off “a bloody gang fight” when some thirty youths gathered at the Carleton Avenue entrance of the Fort Greene Houses “armed with knives, clubs, zip-guns and other makeshift weapons.” Early the next year, a twenty-two-year-old mother of four and wife of an army private serving overseas was slashed to death in her bed as her children slept in the next room. By 1958 there were at least two more killings on the project’s doorstep—a sailor knifed by a group of teens and the stomping death of a youth by rival gang members. Elevators, the weakest link in a high-rise public housing complex, were a particular problem at Fort Greene. The small-cab lifts, unstaffed and claustrophobic, were traps in which muggers and rapists caught many a woman coming home from a late shift. Typical was a case involving nineteen-year-old Adele Rocco, who was returning to her apartment when a man followed her into the lift, brandished a knife, grabbed her purse, and escaped down the staircase. Sluggish and prone to malfunctions, the lifts could barely manage ordinary use and became total choke points with any surge in traffic. When school let out in the afternoon, for example, dozens of restless teens would gather in the lobby for an interminable wait, inevitably leading to trouble. And then there was the piss and filth. “Most visitors to the Fort Greene Houses in Brooklyn prefer to walk up three or four flights instead of taking the elevator,” explained the Times; “They choose the steep, cold staircases rather than face the stench of stale urine that pervades the elevators.”30

Jackie Robinson speaking at the dedication of a playground at the Fort Greene Houses, October 1959. New York City Housing Authority, La Guardia and Wagner Archives.

Vandalism, too, plagued Fort Greene—mailboxes kicked in, lightbulbs smashed or stolen, fire hoses slashed with knives, hall lights ripped out, tree limbs broken, shrubs and flowers trampled, sitting bench slats cracked, split, and burned. The housing authority and its on-site managers were “seemingly helpless,” complained one tenant, “in the face of the constant destruction of project property.” Though there’s no excusing bad-apple tenants for this behavior, much of the vandalism could have been prevented had Fort Greene’s builders made more judicious decisions about design, materials, and construction. The project architects understood the need for toughness and durability, but they also wanted to avoid creating a place so coldly institutional that it resembled a prison or psychiatric hospital. Nor did anybody in 1940 anticipate just how much abuse the model complex would be subjected to. So steel doors were rejected in favor of homey wooden ones, which were quickly carved up. Glass was used in the stair halls and entranceways to foster a sense of transparency and openness, but shattering the costly panes became “one of the forms of amusement for the children in the area,” complained housing authority chief Philip J. Cruise; “we have two gangs of men assigned solely to the task of replacing glass.” Maintenance staff had their hands full even without the vandalism. War-induced shortages had forced the use of inferior materials and equipment throughout the complex. Walls crumbled, elevator mechanisms rusted to the point of failure, and corroded pipes sprang leaks. Barely fifteen years after Fort Greene opened, all of its plumbing had to be replaced and all the walls plastered afresh. The original cut-rate kitchen appliances were swapped out, elevators were upgraded, wooden doors were replaced with steel, and every last piece of glass was pulled out of stairways and entrances. The Times called the $1.3 million upgrade “the biggest home fix-it job” ever undertaken by the housing authority.31

To some critics, however, none of this would remedy the real problem at Fort Greene and nearly every other public housing project in the city at the time—the “bureaucratically produced rootlessness,” as Michael Harrington put it; the fact that at every turn, life in these places was made to feel provisional and impermanent. One of the fiercest was renowned housing advocate Charles Abrams. Son of a Williamsburg pickle-and-herring merchant, Abrams enjoyed a long career in public service—as a lawyer, urban-planning educator, and United Nations consultant. If anyone could call out the New York City Housing Authority, it was Abrams; he had drafted the legislation to create the agency in 1934 and was its first counsel. For all his faith in the welfare state, Abrams concluded that the trouble with public housing was the lack of any sense of proprietorship on the part of residents. The transitionality and impermanence of such housing fostered a pernicious “squatter attitude” that worked against the formation of communal bonds—breeding vandalism and a host of social ills. The solution, Abrams proposed in 1952, was to sell apartment units to tenants as they achieved financial stability. Ownership would counter the “economic ghetto aspects of public housing,” he argued, giving residents “pride and a sense of belonging” and thus helping to eradicate “the slipshod living which is already wrecking new projects like the Fort Greene Houses.” Aware of the political storm such a plan would kick up, Abrams offered an alternative: rather than forcing residents out as their incomes rose, simply raise their rents. This would both stabilize the community and raise desperately needed funds for more housing.32

But Abrams’s advice was not heeded, and the Fort Greene project slowly spiraled into chaos. Born of good intentions but ruined by ill-considered policy, a failed model of urban design, and “blind enforcement of bureaucratic rules,” the celebrated city-in-a-city became more feared than the infamous “Jungle” it had replaced. “Nowhere this side of Moscow,” wrote Salisbury, “are you likely to find public housing so closely duplicating the squalor it was designed to supplant.”33 The dreary Corbusian housing estates he had toured in the Soviet Union had been replicated in Brooklyn, with “the same shoddy shiftlessness, the broken windows, the missing light bulbs, the plaster cracking from the walls . . . the playgrounds that are seas of muddy clay, the bruised and battered trees, the ragged clumps of grass, the planned absence of art, beauty or taste, the gigantic masses of brick, of concrete, of asphalt, the inhuman genius with which our know-how has been perverted to create human cesspools worse than those of yesterday.” Salisbury did not mince his words. He branded New York’s postwar housing projects “fiendishly contrived institutions for the debasing of family and community life to the lowest common mean. They are worse than anything George Orwell ever conceived.”34

In the end it was that most celebrated aspect of the Fort Greene project—its immense, unprecedented scale—that helped turn America’s most progressive housing experiment into a modern ghetto. The Fort Greene Houses concentrated far too many desperately poor families in one place, and a relatively isolated place at that. Abrams understood this well, arguing that public housing must be small and scattered, eased rather than forced into the social and physical fabric of the city. Bigness built the battleships and bombs that won the war, but it was no way to create a lasting, resilient urban community. Thirty years before architects and urban planners embraced a small-scale infill approach to public housing, Abrams urged developing vacant lots throughout the city as a wiser alternative to massive—and massively disruptive—slum-clearance projects. Today, the Fort Greene Houses no longer exists, at least administratively. In a desperate effort to ease the scale of the increasingly unmanageable complex, the housing authority divided it down the middle in 1958. The western half was named after former Brooklyn borough president Raymond V. Ingersoll; the eastern half for Walt Whitman. The largest public housing project in American history was split into history.

Aerial view of the Fort Greene Houses looking east, 1958, showing the long-vanished BMT Myrtle Avenue elevated. America’s largest public housing complex, it was later split administratively into the Walt Whitman and Raymond V. Ingersoll Houses. New York City Housing Authority, La Guardia and Wagner Archives.