CHAPTER 17

HIGHWAY OF HOPE

Of course, not even Robert Moses got everything he wanted. By the mid-1960s, opposition to urban highways was reaching a fever pitch in many American cities. San Franciscans were the first to push back, stirred into action by a map of proposed routes leaked to the press in 1956. Of the dozen-odd highways planned for the city, it was the Embarcadero Freeway that rankled most, the first section of which—a double-decked monstrosity that severed the city from its magnificent waterfront—opened in 1959. Resistance to any further expressway construction in the Bay Area mounted over the next few years. An antifreeway rally in May 1964 drew some 200,000 people to Golden Gate Park. In Louisiana, an artery Moses had himself recommended building—the Vieux Carré Riverfront Expressway—generated tremendous opposition in what came to be known as the “Second Battle of New Orleans.” Well-organized resistance in Boston ended several major highway projects, including the Southwest Expressway and the Inner Belt through Cambridge and Somerville. In New York, Lewis Mumford became a forceful antagonist of the highway lobby, urging Americans to “forget the damned motor car and build cities for lovers and friends.” With persuasive eloquence, he argued that monster expressways were not only destroying the delicate fabric of cities but making traffic congestion worse by dumping thousands of cars where there should be few or none. “In short, the American has sacrificed his life as a whole to the motorcar, like someone who, demented with passion, wrecks his home in order to lavish his income on a capricious mistress who promises delights he can only occasionally enjoy.”1

It was Jane Jacobs who took up the cudgel where Mumford left off with his pen. Though he savaged her Death and Life of Great American Cities in a New Yorker review (“Mother Jacobs’ Home Remedies”), Mumford and Jacobs were strong allies when it came to highways. Jacobs had already battled Moses over plans to extend Fifth Avenue through Washington Square Park and raze a fourteen-block area of her West Village neighborhood for urban renewal. Her most storied fight began in 1962, against an elevated expressway Moses had long planned to plow across lower Manhattan. Like so many projects he brought to fruition, the Lower Manhattan Expressway—or LOMEX, as it was hatefully known—had been recommended decades earlier by the Regional Plan Association, one of five east-west connectors it called for to span the island. The Moses version would run along Broome Street from the Williamsburg Bridge to the Holland Tunnel, conveying traffic between New Jersey and Long Island. At the same time (and contradicting this bypass function), Moses promised that the highway would bring new energy to Manhattan’s dying industrial sector. If the BQE was a defense play, LOMEX was an economic stimulus package. The ten-lane expressway, swimming in a 350-foot-wide right-of-way, would have required demolishing some 400 buildings and displaced 2,200 families and 845 shops, stores, and other commercial establishments.2 It would also have laid waste to the largest concentration of cast-iron architecture in the world, including the magnificent E. V. Haughwout Building at 490 Broadway—a former housewares emporium built with one of the first passenger elevators in the world. The landmarking of this structure by the city’s nascent Landmarks Preservation Commission effectively dropped a boulder in Moses’s path. Bigger ones were soon to come.

Jane Jacobs at a meeting of the Committee to Save the West Village, December 1961. Photograph by Phil Stanziola. New York World-Telegram and the Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

The fate of the Lower Manhattan Expressway was ultimately determined in Brooklyn. Getting across the vast borough had long challenged Moses, to whom it was little more than a congested mess between Manhattan and his beloved Long Island beaches. His maps of Brooklyn slowly filled with dashed lines—planned expressways that would shorten the schlep from city to sand, most of which would become dashed dreams. None of these was more vital to Moses than the Bushwick Expressway. It was proposed by the Regional Plan Association in 1936; Moses called for its construction as early as 1941 and made it part of his infamous 1955 report—Joint Study of Arterial Facilities—that laid out a generation’s worth of megaroads for the metropolitan area. In its original configuration, the Bushwick Expressway was to run southeast across Brooklyn from the Williamsburg Bridge via Broadway or Bushwick Avenue, bending east at Atlantic Avenue to John F. Kennedy Airport via the broad central median of Conduit Boulevard. A northern link to the Queens Midtown Tunnel was added later, ostensibly to relieve traffic on the Long Island Expressway. It would not be an easy build. Some 4,850 families stood in the way of the original alignment, twice the number impacted by LOMEX and three times the number eventually displaced by the Cross Bronx Expressway. Yet Moses forged ahead, bucking a growing local and national backlash against neighborhood-wrecking road projects. He did so because building the Bushwick Expressway would all but assure his victory in the LOMEX fight. To Moses, LOMEX and the Bushwick Expressway were two segments of the same arterial. In a 1963 report on highway construction, he even referred to the Bushwick route as “an extension of the Lower Manhattan Expressway through the northerly and heretofore neglected sector of Brooklyn.”3 Moses reasoned that if the Bushwick road were built, it would channel such a flood of traffic from Long Island onto lower Manhattan’s congested streets that the city would be forced to build LOMEX too. But by the mid-1960s, political winds were blowing strongly against Moses in both city and state. The newly elected Republican mayor, John Vliet Lindsay, had campaigned on a platform that included support for mass transit and an end to LOMEX; for “cities are for people,” he said repeatedly on the campaign trail, “not for automobiles.”4 Though he reneged on LOMEX, as we will see, Lindsay was fundamentally opposed to highways and the man who had been imposing them on the city for decades. Now, for the same reasons that Moses wanted to build the Bushwick Expressway, the young mayor sought to kill it. LOMEX without the new link across Brooklyn would feed fatal loads of traffic onto the already-overburdened Brooklyn-Queens and Long Island expressways. Killing the Bushwick Expressway, Lindsay realized, would make LOMEX a road to nowhere.

The Lower Manhattan Expressway (LOMEX). From Future Arterial Program (Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority, 1963).

The City Planning Commission, long in the Moses camp, had just that summer recommended prioritizing another Brooklyn road over the Bushwick project—the Cross-Brooklyn Expressway. Outraged, Moses demanded that the commission withdraw the substitution. Commission chairman William F. R. Ballard—a Wagner appointee and Moses adversary—refused.5 Unlike nearly every other expressway in postwar New York, the Cross-Brooklyn actually made sense. Not only would it provide commercial traffic an alternative to the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway—all of five years old but already overloaded—but it would “divert a maximum amount of through traffic,” stressed Ballard, “from the congested Manhattan core,” channeling it instead over the newly opened Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge. Equally compelling, the Cross-Brooklyn would unlock Brooklyn’s sprawling southeastern quarter to industrial development, which the city itself had been promoting for years at its Flatlands Industrial Park. Launched in January 1959, the project was a last echo of the manufacturing sector pitched as part of the Jamaica Bay port scheme—and a late, ultimately futile attempt by Mayor Richard F. Wagner, Jr., to stem the postwar outflow of industry from Brooklyn by providing modern factory space within city limits.6 It was an idea so novel at the time that press stories on the Flatlands initiative routinely placed “industrial park” in quotes (North Carolina’s Research Triangle Park had yet to open, and the fabled Stanford Industrial Park, birthplace of Silicon Valley, was just several years old). Though the projected zone already had a major tenant—the Brooklyn Terminal Market, opened in 1942 to replace Wallabout Market, razed for a wartime expansion of the Navy Yard—the project floundered for years. Paltry incentives and—especially—the lack of easy access to the regional highway system made finding tenants difficult. Project management changed; a new master plan was solicited. Tishman Realty proposed an innovative multistory live-work industrial village by shopping mall sage Victor Gruen, anchored by the East 105th Street subway station. Instead, the city went with a plodding array of single-story superblocks. The project ultimately shriveled from 680 acres to a mere 96. And even that proved too much: by 1966 not a single shovelful of dirt had been turned. A Lindsay subordinate sent to the site that spring reported finding “a glacier of mouldy mattresses, unsprung sofas and a strange gamut of debris.” The much-heralded village of industry had become instead “the most expensive garbage dump in the city.”7

The planned Bushwick Expressway as it was to connect with the Lower and Mid-Manhattan expressways. Moses described the Bushwick arterial as “an extension of the Lower Manhattan Expressway through the northerly and heretofore neglected sector of Brooklyn.” When the Lindsay administration refused to approve the Bushwick route, it effectively also killed LOMEX. From Future Arterial Program (Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority, 1963).

Sane and an easy build, the Cross-Brooklyn Expressway gained many supporters. The New York Times contended that the expressway would “enable a huge volume of traffic to flow from Brooklyn and Long Island to New Jersey and the South,” and affirmed that “the City Planning Commission is right in arguing that future highways should not be built where they will pour more automobiles into lower Manhattan.” The city’s traffic commissioner, Henry A. Barnes—a Moses rival and public transit advocate (when asked once what to do with a car in Manhattan, he said “sell it”)—also favored the Cross-Brooklyn road over Bushwick. The matter came to a head on July 6, 1966, when Governor Nelson Rockefeller signed a bill eliminating the Bushwick Expressway “and designating the Cross-Brooklyn expressway . . . in place thereof.” The eastern extension of LOMEX was thus stricken from the state’s map of arterial projects. When, the following week, a vengeful Moses announced that $40 million in surplus authority funds would be used for highway bridge improvements—money Lindsay had hoped to use for public transit—the new mayor promptly dismissed Moses from his post as the city’s arterial coordinator. The great irony here is that the Cross-Brooklyn project was first proposed by Moses himself, and in the same 1955 Joint Study that called for the Bushwick Expressway. In that report, a dotted “Cross Brooklyn Expressway” is shown leading east from a great span across the Narrows, twelve lanes wide and nearly three miles long—the future Verrazzano-Narrows Bridge—joining the Bushwick Expressway just past the Queens line near the Belt Parkway and Idlewild Airport.8

Watermelon race at the Brooklyn Terminal Market in Flatlands, 1964. Photograph by Phyllis Twachtman. New York World-Telegram and the Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Both a Narrows crossing and a highway across Brooklyn had been recommended decades earlier by, once again, Thomas Adams and the Regional Plan Association. They were part of a “Metropolitan Loop or belt line highway” proposed in 1928 to facilitate regional freight traffic and “relieve pressure upon the street system of Manhattan”—what Peter Hall called “the first true orbital motorway in the world.”9 For the Brooklyn segment of this great loop, Adams suggested using Eighty-Sixth Street, Kings Highway, and Flatlands Avenue—an alignment that would have gutted neighborhoods from Dyker Heights to East Flatbush. Moses wisely favored instead using a quiet freight rail corridor to get the artery across Brooklyn—the Bay Ridge Branch of the Long Island Rail Road, which arcs across the borough from Brooklyn Army Terminal to East New York (joining there the New York Connecting Railroad). By using an extant transit corridor, the Cross-Brooklyn would have dislodged fewer families or businesses than any other highway in postwar New York. But fixated as he was on LOMEX, Moses put all his eggs in the Bushwick basket. In mid-December 1966, with his power waning fast, Moses begrudgingly agreed to support the Cross-Brooklyn road, but only if his rejected Bushwick Expressway was also built. He armed himself with a report by a trusted Triborough consultant, Blauvelt Engineering, which concluded that the Cross-Brooklyn Expressway was “no substitute for the Bushwick Expressway,” and that both were necessary to handle projected loads of transborough traffic. Building either road without the other, in other words, would be a waste of taxpayer money.10

The Lindsay administration fired back with a study of its own, by the Brill Engineering Corporation, whose principal, former city highways commissioner John T. Carroll, advised that the only fix for “intolerable” traffic conditions in Brooklyn—“the largest community in the country without interior access to an expressway”—was to build the Cross-Brooklyn route as soon as possible. Not only would the road patch borough commerce and manufacturing into the regional highway network, making Flatlands Industrial Park readily accessible by trucks, but it would take traffic pressure off both the BQE and the Belt Parkway while completing the long-envisioned “southern bypass of New York City’s central business areas.” Much the same had been said before, of course. But the report also recommended joining the easternmost section of the Cross-Brooklyn Expressway corridor and the New York Connecting Railroad to create “a future high-speed rapid transit link” between John, F. Kennedy Airport and Manhattan—a perennial dream of every New Yorker who’s had to endure a long, smelly cab ride home from Queens. Brill further counseled the city to acquire the air rights above the new highway for development—an idea first put into practice a decade earlier along the FDR Drive. The busy expressway-rail corridor could be transformed “from an eyesore to a pleasing architectural experience,” the report noted, “by the addition of housing, schools, vest-pocket parks, playgrounds and sitting areas along and above the right-of-way.”11

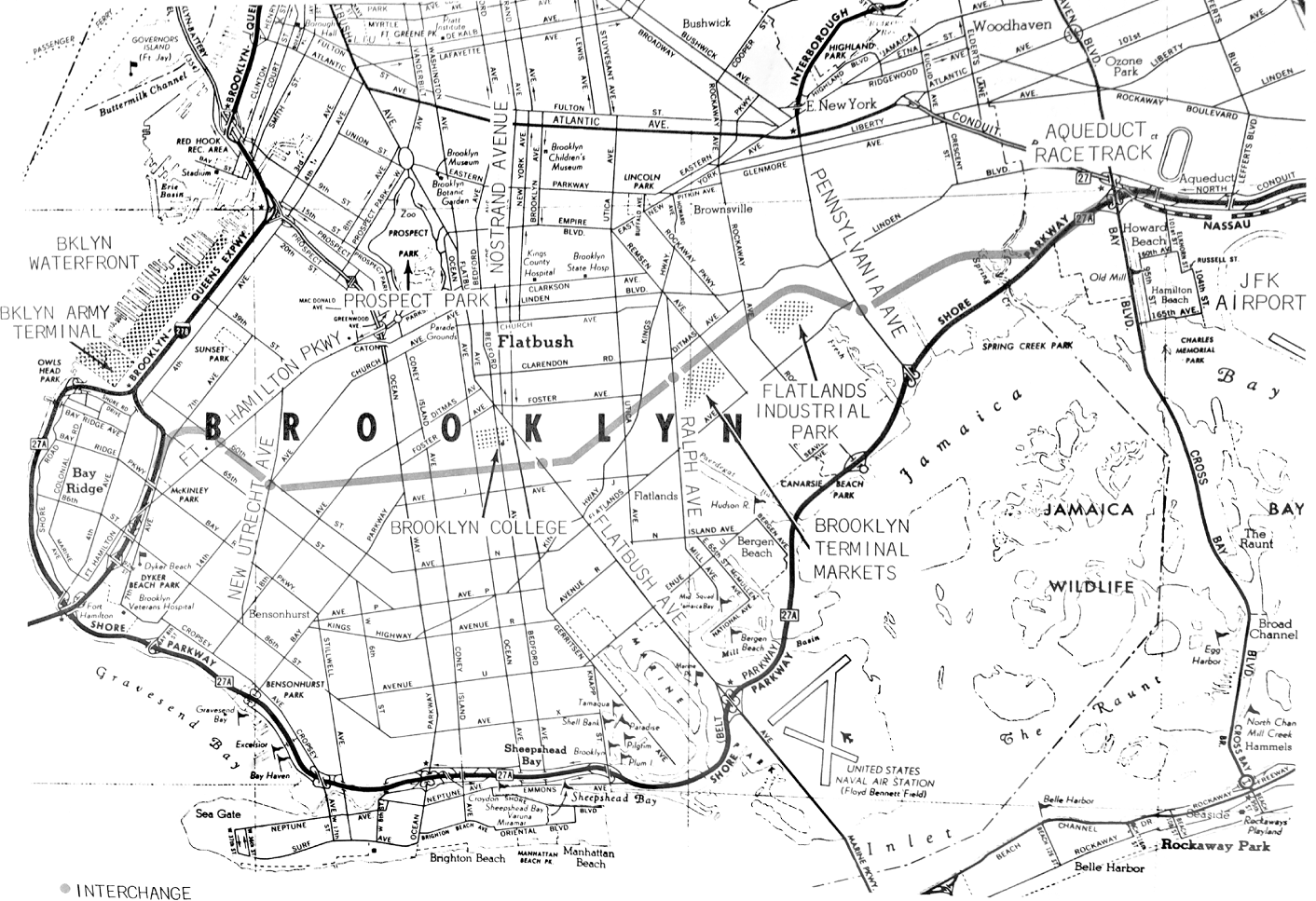

Route of proposed Cross-Brooklyn Expressway (gray line across center). From Brill Engineering Corporation, Cross Brooklyn Expressway: Benefits for Brooklyn (1967).

If Carroll’s report was the first to suggest building atop the Cross-Brooklyn artery, it was an exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art that revealed the full potential latent in the Brooklyn air. It was called The New City: Architecture and Urban Renewal, and Mayor Lindsay himself opened it on January 20—just days after receiving the Brill study. Featured were speculative urban design projects by student-practitioner teams from Columbia, Princeton, Cornell, and MIT. Each proposed interventions to create new housing, parks, and neighborhoods. The Columbia group was led by a quintet of young architects—Jaquelin T. Robertson, Richard Weinstein, Giovanni Pasanella, Jonathan Barnett, and Myles Weintraub. They focused on redeveloping the Penn Central railroad right-of-way along Park Avenue in Harlem. As any Metro-North rider knows, when trains leaving Grand Central emerge into daylight at Ninety-Seventh Street, first a ponderous brownstone viaduct and then a steel el structure carries them toward the Harlem River. All the grace and elegance of lower Park Avenue is obliterated by this infrastructure, which has long divided the Harlem community. The Columbia team proposed using the air rights above the tracks for a development program to stitch together Harlem’s fabric, removing the blight of the tracks while making room for housing and other community amenities.12

Ilustrative rendering of air-rights development above Cross-Brooklyn Expressway. From Brill Engineering Corporation, Cross Brooklyn Expressway: Benefits for Brooklyn (1967).

The MoMA show came at a time of resurgent interest in the future of cities, and in the transformative potential of city design. Jacobs published her searing critique of superblock modernism and the failures of urban renewal in 1961. A whole new field—urban design—was forming out of the ashes of the city-planning profession, self-immolated for having midwifed the disastrous urban renewal program. Architects around the world, weary of orthodox modernism, were exploring urban-architectural systems as heroic in scale as in social ambition. Team 10 and Archigram in Europe and the United Kingdom and the metabolists in Japan experimented with megastructural forms that combined all the functions of the traditional city in exciting new ways. Japanese architect Kenzo Tange’s students proposed a city for twenty-five thousand in Boston Harbor in 1959, and an even larger project for Tokyo Bay the following year. In the fall of 1964, Norval White’s thesis students at Cooper Union drafted a bold plan for a network of hyperdense pyramidal towers on Staten Island structured about multimodal transit lines. There was even a “Design-In” on the Central Park Mall, organized by New York University and the Department of Parks. The May 1967 event brought together citizens, architects, and planners committed to applying lessons of political action to the urban crisis. It was a kaleido-scopic affair, with hippies checking out electric cars and geodesic domes to music by the Department of Sanitation Band. Among the many speakers were then council-man Edward Koch and Thomas Hoving, pompous director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and Lindsay’s first commissioner of parks. Lindsay himself gave the closing speech.13

For all his patrician airs, Lindsay was a committed urbanist—deeply concerned about New York’s built environment and enthusiastic about the potential of architecture and urban design to make the city a better place for all. “We are fast becoming a nation of cities, indeed a world of cities,” he wrote, “and their problems and promise must occupy the forefront of national concern.” Soon after taking office in January 1966, the new mayor called upon Boston Redevelopment Authority chief Edward, J. Logue for advice on slum redevelopment, asking him to chair a Study Group on New York Housing and Neighborhood Improvement. Lindsay called the group’s report—provocatively titled Let There Be Commitment—a “brilliant, penetrating analysis” of the city’s housing problems. It concluded that New York needed some 450,000 new apartments, which should be built by a new housing and development agency with authority over all aspects of the planning, design, and construction process. A supplement by architects David A. Crane and Tunney F. Lee, Logue associates from Boston, focused specifically on urban design problems facing the city. Lindsay responded by appointing a Task Force on Urban Design charged with envisioning new ways for the city to manage increasingly complex problems of urban development. Chaired by CBS chief William S. Paley, it included I. M. Pei, Robert A. M. Stern, and philanthropist Joan K. Davidson of the J. M. Kaplan Fund. Its report, The Threatened City, described New York as blighted by “depressingly blank architecture, arid street scenes and baleful housing conditions,” and recommended, among other things, appointing “an urban design force of trained professionals of the highest competence” to advise the mayor. Lindsay concurred and in April 1967 assembled an elite advisory corps of architects within the City Planning Commission known as the Urban Design Group. “Design is not a small enterprise in New York City today,” he later explained; “In our increasingly crowded, man-shaped urban world, esthetics must now include not only the marble statue in the garden, but the house, the street, the neighborhood and the city, as a cumulative expression of its residents.”14

The original Urban Design Group, not coincidentally, consisted of the same team of young architects that produced the Park Avenue air-rights scheme for the New City exhibition—Robertson, Barnett, Weinstein, Pasanella, and Weintraub. It was Jaque Robertson who had urged Barnett and the others to seek work in the new administration. As Barnett tells it, all five headed down to City Hall one day to meet with the new chair of the City Planning Commission, Donald H. Elliott. Unbeknownst to them, Elliott’s first design advisers, including Norval White and Elliot Willensky (whose iconic AIA Guide to New York had just been published), had just that morning quit in a huff. He needed a new team and decided to take his chances with the eager band at his door.15 The Urban Design Group came to epitomize Lindsay’s penchant for stocking his administration with “bright young people of wit, zeal and imagination.” It was all white, all male, and nearly all Yale—hardly a reflection of the city’s surging diversity at the time. Nonetheless, the group brought real expertise to what had been a bloated, largely ineffectual city agency—“understaffed, underbudgeted and undertalented,” as the New York Times put it, with just one architect on payroll. “The planning task and responsibility,” Elliott explained, “must be placed in the hands of experts who are at once creative and disciplined, visionary and sure-footed when traversing bureaucratic terrain.” Thus by the summer of 1967 John Lindsay had fortified City Hall with more architecture and urban design know-how than any administration since La Guardia’s. And it was expertise urgently needed; for the city seemed to be falling apart. “To a New Yorker born and bred such as myself,” wrote Allan Temko, longtime architecture critic of the San Francisco Chronicle, “the great city at times appears to be spinning towards Mumfordian doom; overgrown, over-congested, ill-managed and ill-kempt, usually sullen, sometimes violent, and scarred by enormous ‘gray areas.’”16

Mayor John Lindsay speaking at a street rally, 1965. Photograph by Walter Albertin. New York World-Telegram and the Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Few places in New York needed help more desperately than Brooklyn’s easternmost neighborhoods of Brownsville and East New York. Never an affluent part of the city, it had been home to working-class Jews and Italians from the Lower East Side who moved there in large numbers once the Williamsburg Bridge opened in 1903. By the 1920s Brownsville was more than 75 percent Jewish, known as the “Jerusalem of America.” A progressive hotbed, it regularly elected socialists to the New York State Assembly and was the site of the first birth control clinic in the, United States—opened by Margaret Sanger at 46 Amboy Street. It produced scores of Jewish intellectuals—Norman Podhoretz, Isaac Asimov, George Gershwin, and literary critic Alfred Kazin, whose 1951 book, A Walker in the City, chronicled the Sutter Avenue world of his youth. To Kazin, Brownsville was “New York’s rawest, remotest, cheapest ghetto, enclosed on one side by the Canarsie flats and on the other by the hallowed middle class districts that showed the way to New York.” Like so many other Brooklyn neighborhoods, Brownsville and East New York changed rapidly after World War II. African Americans began moving in, driven by rising rents and overcrowding in adjacent Bedford-Stuyvesant; the influx topped twelve hundred people per month by the late 1950s. Many of the new families were desperately poor, some arriving penniless straight from North Carolina, Virginia, and other southern states. Residents blamed social service agencies for sending them the poorest of the poor, making their neighborhoods “the biggest dumping ground for welfare cases in the city.” With poverty and despair came crime. Arrests in the Seventy-Third Precinct, spanning Brownsville and Ocean Hill, more than doubled between 1956 and 1966; homicides rose by 200 percent between 1960 and 1967 alone. In December 1966 an elderly tailor named Hyman Getnick was stabbed to death by teenagers for a fistful of dollars. The crime shocked a city still reeling from the Kitty Genovese murder two years earlier. Synagogues were broken into and stripped of anything of value. Pitkin Avenue merchants cowered behind steel gates; many had already been held up or burgled several times. There were violent street fights between blacks and Italians, blacks and Jews, blacks and Puerto Ricans. The clashes peaked in the summer of 1966, leading to an exodus of dozens of families—black and white—and pleas for calm from City Hall.17

As African Americans poured into Brownsville and East New York, whites fled—to nearby Canarsie and Mill Basin, or the suburbs of Queens and Long Island. Prejudice and racial animosity were powerful motivating forces, but the real driver was fear—fear of crime, fear of violence, fear of realtor-led blockbusting that could vaporize the value of a family home overnight. Between 1950 and 1960, 38 percent of Brownsville’s whites moved out of the area. Its population in 1960 was 43 percent black or Puerto Rican; by mid-decade, that figure had topped 95 percent. Always distant from the centers of culture and commerce in the city, Brownsville was now a kind of quarantine zone, a place that “symbolized the economic, geographic, political and educational isolation of New York’s black community.” Linden Boulevard became a border of sorts, a “redline” separating the ghetto from still-white Canarsie to the south. “An unspoken assumption existed among Canarsie residents,” writes Jerald E. Podair, “that blacks from Ocean Hill–Brownsville would not be permitted to move across Linden Boulevard in appreciable numbers” (Canarsie’s pricier real estate effectively assured this). By the time Lindsay became mayor, Brownsville and East New York were plagued by a gamut of social ills—from a welfare rate double the city average (with 75 percent of residents on public assistance) to unemployment five times that of the rest of New York. Drug addiction, juvenile crime, rape, and out-of-wedlock birth rates were all among the highest in the city. But it was the deplorable state of the public schools in Brownsville and East New York that most troubled community leaders and city officials. At the district’s new flagship junior high school on Herkimer Street—now John M. Coleman Intermediate School 271—“reading and math scores were among the lowest in the city, with 73 percent of its pupils below grade in reading and 85 percent in math.” With discipline poor, attacks on teachers common, and acts of vandalism routine, “it was clear,” Podair writes, “that education of a very different sort was taking place in Ocean Hill–Brownsville and the white majority schools of the city.”18

It was the issue of school quality and segregation in this embattled quarter of Brooklyn that ultimately transformed the Cross-Brooklyn Expressway from a straightforward road play into one of the most promising public works of the 1960s—a Moses-style arterial project leavened with the insurgent idealism of Jane Jacobs and the civil rights movement. In the wake of Brown v. Board of Education it was taken on faith that segregated schools were bad, and that integrating classrooms would improve learning outcomes for minority children. “The racial imbalance existing in a school in which the enrollment is wholly or predominantly Negro,” argued New York State commissioner of education James E. Allen, Jr., “interferes with the achievement of equality of educational opportunity and must therefore be eliminated.”19 But unlike the South, where blacks and whites were kept separate by Jim Crow laws, school segregation in the North was largely a function of residential demographics. Schools in predominately white neighborhoods had mostly white student bodies, and vice versa. In Brownsville’s District 17, the percentage of white students had fallen from 53 to 17 percent between 1958 and 1966, making racially integrated schools there a virtual impossibility.20 Integration thus called for a lot more than declaring certain laws unconstitutional. It would require, for example, reconfiguring school-district boundaries, building new schools on community borders, or transporting students twice a day between neighborhoods. Busing, as this last option came to be known, was especially controversial. Conservatives were fundamentally opposed to it, and for progressives it contradicted core values of the local and the grassroots. As the decade wore on, more and more black parents would come to suspect the whole project of integration. After all, the idea that thinning densities of African American students would improve outcomes—that black children could do well only with whites around—was itself intrinsically racist.21

“They want action against hoodlums.” East New York mothers and kids rally against street violence at Atlantic Avenue overpass, August 1953. Photograph by Johnny Kruh. Brooklyn Public Library, Brooklyn Collection.

In the decade following Brown, the Board of Education tried but largely failed to integrate the city’s schools, many of which were declining fast in terms of academic performance. It thus fell to the Lindsay administration to reform the nation’s largest school system and make it compliant with the 1954 Supreme Court ruling. Sidestepping the integration issue, Lindsay and his advisers focused on improving schools in minority neighborhoods—a goal they believed would best be met by making the monolithic Board of Education more responsive to local community needs. Lindsay appointed an advisory panel to study the matter—chaired, ironically, by former national security advisor McGeorge Bundy, architect of America’s disastrous plunge into Vietnam. Now head of the Ford Foundation and a professor of government at Harvard, Bundy and his panel recommended replacing the city’s colossal education bureaucracy with a more nimble federation of school districts administered by boards staffed at the community level. The Bundy proposal was fiercely opposed by the Board of Education and the teachers’ union, and much diluted by the time its recommendations went off to Albany in the form of a bill. A consortium of parents and civic groups from Brownsville, meanwhile, had been battling the Board of Education over district zoning and school siting since early 1963. For its part, board officials knew well how dire the situation had become in Brownsville and East New York. With class sizes pushing sixty pupils in some schools, new facilities were desperately needed. In response, the board proposed constructing seven new schools across Canarsie, Brownsville, and East New York. The parents feared the new schools would be segregated upon opening, as all were sited well within largely white or black neighborhoods. Drawing on the work of educational sociologist Max Wolff, they called instead for a single campus-like school complex for fifteen thousand pupils at the junction of Canarsie, Brownsville, and East New York—on the very spot, in fact, where the city was trying to launch its star-crossed Flatlands Industrial Park. Wolff—then research director for the Migration Division of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico—considered southeast Brooklyn ideal for an “educational park” where a vibrant mix of white, black, and brown students would come together as one and ease “the fetters of poverty and discrimination from minority groups and the poor.”22

Industrial-scale education was not a new idea. As early as 1900, Los Angeles school superintendent Preston Search proposed a two-hundred-acre “school park” for the entire student population, with a farm-like setting to remove pupils from “smoking chimneys and congested urban conditions.” Similar plans for school complexes accommodating up to ten thousand pupils were envisioned for Detroit and Glencoe, Illinois, during the Depression, and in the postwar era by officials in New Orleans, Albuquerque, and Pittsburgh. One of the few to become reality was in Fort Lauderdale, where a 546-acre “South Florida Education Park” was proposed for a former naval air field in March 1960. Funded by the Educational Facilities Laboratories of the Ford Foundation and later renamed the Nova Educational Experiment, the facility covered all levels of learning—“from nursery school through the Ph.D.”—and was anticipated to establish a pattern for school districts nationally. New York City first began seriously considering education parks at a two-day conference in June 1964 organized by the Board of Education. Held at the Harriman estate near Bear Mountain, it brought school officials from New York and other cities together with experts from the Ford Foundation—led by a Harvard colleague of McGeorge Bundy’s, Cyril G. Sargent. In his closing remarks, Sargent noted that while education parks were worth trying “on an experimental or prototype basis” in New York, they were not “a panacea nor a cure-all” for educating urban youth or reducing racial imbalance. Board of Education acting president Lloyd K. Garrison—great-grandson of famed abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison—was amenable to the idea but called for further study. “We laid groundwork here on which we can usefully build,” he said at the end of the Harriman meeting; “This is not a matter to be decided overnight.”23

By September 1965 Garrison and the board had provisionally approved two education parks for New York City, both in the Bronx—one on the former site of Freedomland, a short-lived theme park (today the Northeast Bronx Education Park at Co-op City), and one in Marble Hill, anchored by the future—and ill-fated—John F. Kennedy High School (closed in 2014). But they vetoed the Flatlands park proposed by the Brownsville parents, explaining that it should not be built “until the first two could be appraised for their merits.” The parents were outraged, claiming that the board was wielding its construction budget “as an illegal instrument to perpetuate segregation,” and that in canceling Flatlands the board was effectively entrenching “an apartheid system in New York.” The following May, Brownsville activists led by Harlem minister Milton A. Galamison petitioned state education commissioner James Allen to stop the seven-schools scheme. Allen concurred, restraining the Board of Education from going ahead with its construction plans—temporarily, at least, pending outcome of a hearing on the parents’ appeal for a state order to compel the board to establish “a centrally-located educational park . . . that would draw pupils from an ethnically varied population.”24

Matters reached a head on July 19, 1966, opening day of the long-awaited Flatlands Industrial Park. A large and noisy throng of protesters had gathered, shouting, “Jim Crow Must Go,” and denouncing the city for choosing industry over schoolchildren and failing to build the Flatlands education park. Befuddled dignitaries sat before a stage full of worried officials, all anxiously waiting for Mayor Lindsay to arrive. When his black sedan slowly pulled up, they were shocked to see Lindsay get out and walk unescorted into the crowd of demonstrators. “There was a moment of startled silence,” reported the Times; “Then the chants of anger turned to cheers as a half-dozen burly Negro youths lifted the Mayor to their shoulders and carried him through the throng.” The moment was not without effect; for several weeks later the Board of Education reversed itself, announcing that it was now considering an education park in the Brownsville–East New York area. It ultimately proposed a pair of parks, one in East Flatbush and one on the eastern edge of East New York. Both were far from the core of Brownsville–East New York, and purposely so. As Walter Thabit recounted in How East New York Became a Ghetto, Board of Education planners “felt that if the parks were in or near white areas, they would have a better chance of being integrated”—a point the Brownsville activists, too, had themselves argued for years. With the board and the parents now at loggerheads, the city that fall commissioned a Connecticut consulting firm, Community Research and Development (CORDE), to decide which of the proposals—the parents’ or the Board of Education’s—had greater merit.25

CORDE pulled together a team of experts for this Solomonic task, led by Cy Sargent and a junior colleague named Allan R. Talbot. Scion of the famed Boston family, Sargent was Bundy’s collaborator at the Ford Foundation and a professor at the Harvard Graduate School of Education. He was best known—even notorious—for authoring a controversial 1953 study of the Boston public school system that recommended closing sixty-eight obsolete facilities across the city. A decade later Sargent was asked by Ed Logue, newly appointed head of the Boston Redevelopment Authority, to update the so-called Sargent Report. In his second study (1962), Sargent urged tapping federal urban renewal funds to build scores of new inner-city schools—including a thirty-acre centralized “Campus High School” to which students would come “from every part of the City, of every background, of every intellectual level and every talent.” The idea of centralized megaschools had become a hot one by now, especially at Harvard, where the Ford Foundation was funding research on their potential to reduce racial segregation. Logue knew Sargent from his days as redevelopment chief of New Haven, where the latter helped create a school for Logue’s lauded Wooster Square renewal project. Sargent intended the facility—now the Harry A. Conte West Hills Magnet School—to serve as a hub of communal life in Wooster Square. The complex was eventually designed by Gordon Bunshaft and Natalie de Blois of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, and included a senior center, library, auditorium, recreation room, gymnasium, hockey rink, pool, and playground. Allan Talbot had worked closely with both Sargent and Logue at the New Haven Redevelopment Agency and had just published a book on Mayor Richard Lee’s efforts to transform New Haven into a “slumless city”—The Mayor’s Game (1967). The Queens native was already back in town, for Logue had tapped him to serve on his Study Group on New York Housing and Neighborhood Improvement.26

Parachuting in, as it were, Talbot and Sargent could see from above what the embattled partisans in the schools fight could not. They immediately realized that both the parents and the Board of Education had overlooked critical demographic and land use data in their respective proposals, both of which “seemed to have been developed in a planning vacuum.” Most glaring was a failure to account for the Cross-Brooklyn Expressway, which—extending across the entire district—effectively rendered both plans untenable. As Talbot and Sargent put it, the arterial would “cut through part of one of the sites proposed by the school staff and partially isolate the Flatlands site proposed by the parents.” Worse, it would drive a divisive wedge between East Flatbush and Canarsie, Brownsville and East New York. In short, “the huge public investments represented by the expressway and the schools were in direct conflict with each other.” To Talbot and Sargent, the situation had all the ingredients for a municipal planning disaster—“a lack of precise demographic data, massive housing construction unrelated to total community planning, unchecked blight . . . and the clash of a highway alignment with school sites.” The solution Talbot and Sargent came up with was a stroke of liability-to-asset genius. To them, the old Long Island Rail Road cut seemed to be the one thing that united the disparate neighborhoods from Midwood to East New York. “The line is a landmark,” they wrote, “a strong physical symbol shared by each of the five communities . . . the line unites the entire area.” What nearly everyone saw as an immutable barrier—not unlike Harlem’s Park Avenue viaduct—Talbot and Sargent recognized as a key to renewing East Central Brooklyn. How? By building over it an array of public amenities that would create a shared center of gravity for all the communities along the Cross-Brooklyn Expressway—Midwood, East Flatbush, Canarsie, Brownsville, and East New York. They called it “A Linear City for New York.”27

Of course, Jack Carroll had already recommended building above the corridor in the Brill report, but only at selected nodes and not as a contiguous megastructure. Moreover, he projected doing so only at the western end of the expressway, through Borough Park, Kensington, and West Midwood—stable, relatively affluent neighborhoods where the city could expect to “reap . . . maximum benefit” from infill development. For Talbot and Sargent, building at the eastern end of the expressway had nothing to do with municipal return on investment; it was an act of intensive care, suturing an urban wound. For decades, expressways had torn apart urban neighborhoods; here, perhaps, was a highway of hope, a road that might heal Gotham’s most embattled quarter. Over the rail-and-road core would be six thousand units of housing, shops, and stores, a cultural center, fine arts museum, parks, playgrounds, and recreation facilities—all served by a local “rail bus.” First and foremost, however, Linear City was learning infrastructure—a great extruded education park anchored at one end by Brooklyn College and at the other by a new community college. In between would be an array of classroom and performance spaces and specialized facilities for the study of science, technology, and the arts. “In effect, children would be in school once they arrived at stops along the transportation line closest to their homes,” the consultants wrote, enabling students to “spend part of or a full day—or perhaps a month—at a humanities, sciences or social sciences center”—all according to individual need or preference. The same facilities could be used in the evening for adult education. Thus—in a complete reversal of what had gone before—this major piece of arterial infrastructure would not lay waste communities but rather “result in a revitalized city within a city . . . stable, environmentally pleasing, and capable of offering the urban dweller conditions for the attainment of his personal aspirations.”28

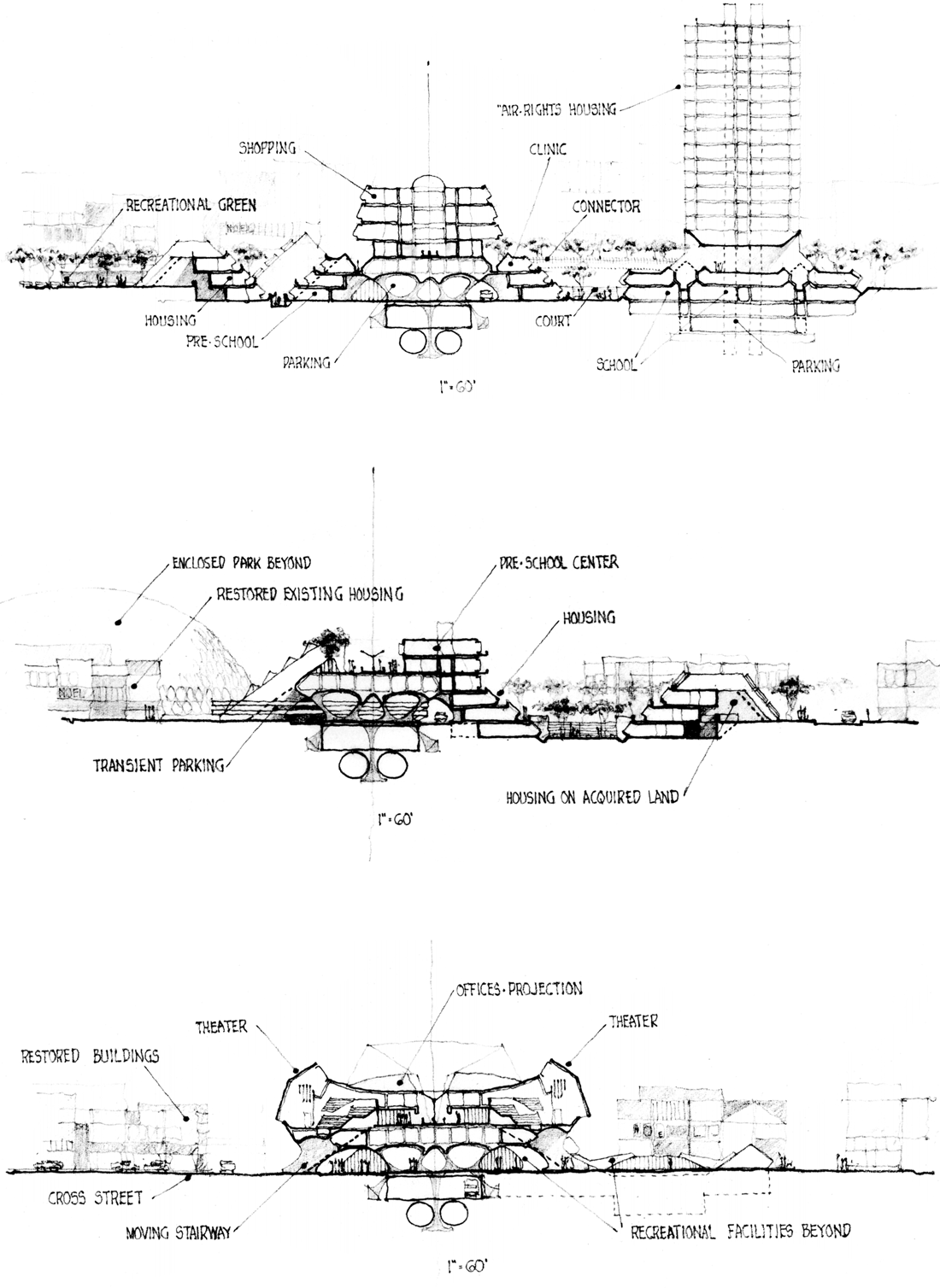

Architectural sections through communal spine of Cross-Brooklyn Expressway, showing housing, recreation facilities, and other civic amenities. From McMillan Griffis Mileto, Linear City, Brooklyn, New York: Feasibility Study and Planning (1967).

Lindsay loved it and immediately directed his staff to procure a feasibility study. The firm they commissioned—McMillan Griffis Mileto (MGM)—was itself recommended by Sargent and possessed a wealth of experience in educational facility design. Its principal, Robert S. McMillan, had been a founding partner, with Walter Gropius, of The Architects Collaborative (TAC) and played a lead role on the Pan Am Building, Harvard Graduate Center, and the US Embassy in Athens. He had worked with Sargent on a spectacular plan for the University of Baghdad, complete with dormitories, a shopping center, teaching hospital, and mosque. John, H. Griffis, another former Gropius associate, led projects for the Libyan Health Ministry and for the Aga Khan in Sardinia, Kenya, and Ethiopia. The firm’s youngest partner, William P. Mileto, was an Italian émigré who had studied at the University of Rome and taught design at Pratt Institute. He, too, had a connection to Cy Sargent, having worked with him, Logue, and Talbot in New Haven. There, Mileto designed an award-winning ensemble of townhouses within the Wooster Square Redevelopment, the Neighborhood Music School on Audubon Street, and the innovative North Quinnipiac Elementary School, with its array of sunken spaces for small-group teaching. An eclectic builder, Mileto spearheaded projects including everything from suburban Connecticut supermarkets to parliamentary buildings in Africa; he even supervised the marble contracts in Italy for the Kennedy Center for Performing Arts. Among them, the MGM principals had designed dozens of school and university buildings in New England, Europe, Africa, and the Middle East, and prepared master plans for the University of Lagos and Pahlavi (now Shiraz) University in Iran. If anyone could build an extended superschool in Brooklyn, it was McMillan, Griffis, and Mileto.29

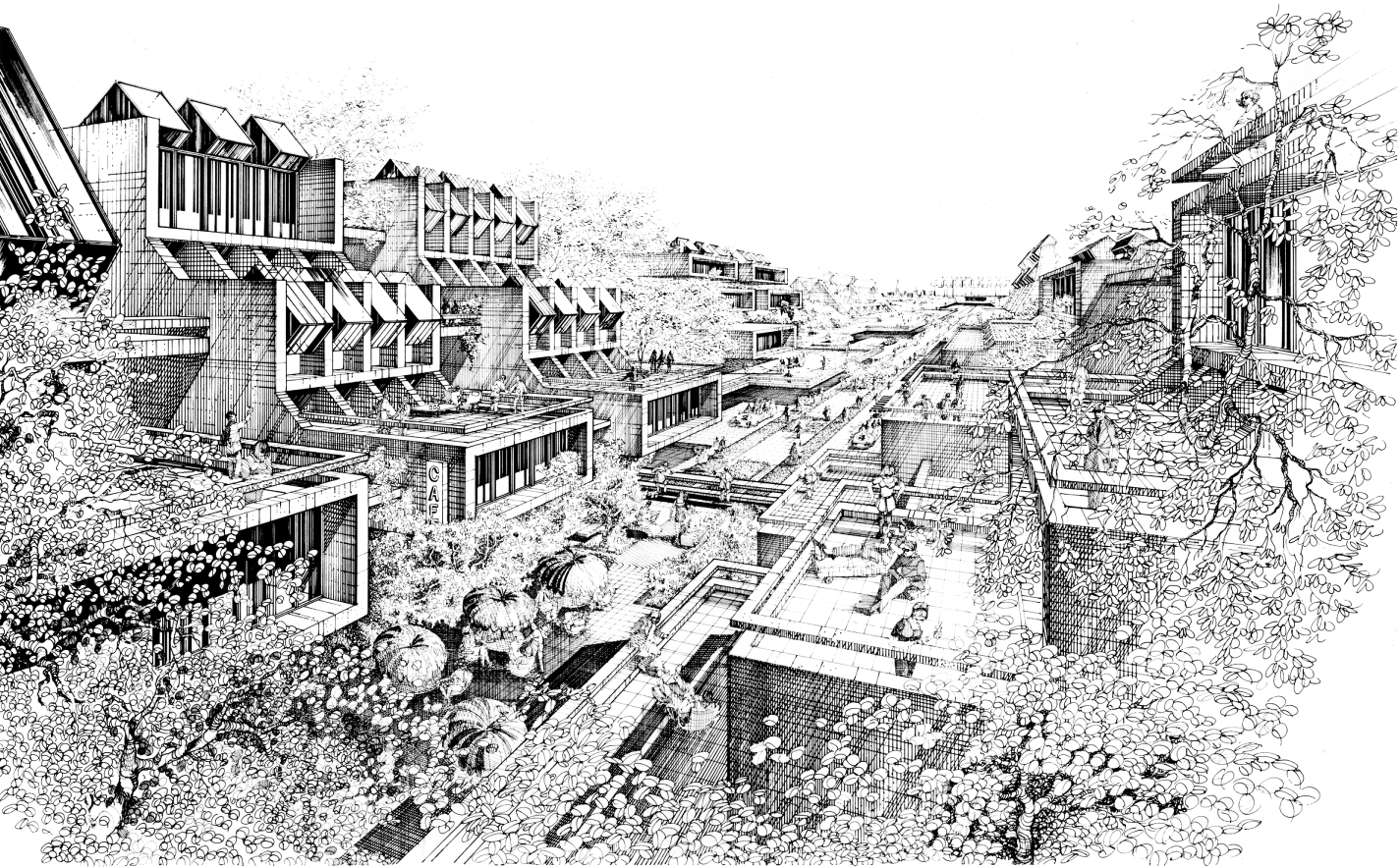

Jane Jacobs meets Robert Moses: perspective rendering showing residential neighborhood along spine of Cross-Brooklyn Expressway. From McMillan Griffis Mileto, Linear City, Brooklyn, New York: Feasibility Study and Planning (1967).

For Linear City, the trio envisioned “an integrated complex of buildings and public spaces” arranged along the road-rail spine like notes on a musical staff—with social services facilities, public housing, playgrounds, shopping centers, an industrial park, schools, and an array of suspended pedestrian platforms. All this would be carefully stitched into the surrounding urban fabric, “kept in sympathic harmony with relation to the existing communities” and minimizing “indiscriminate use of high-rise architecture.” The linear complex, more than five miles long from end to end, would be “interrupted at key points, touching the ground and laterally expanding in the form of nodular configurations” and in response to the availability of city-owned or derelict land on either side. This was the first American attempt to realize a form of urbanism that had fascinated architects and planners for almost a century. Its earliest iteration came from a Spanish town planner named Arturo Soria y Mata, whose 1882 “Ciudad Lineal” anticipated Ebenezer Howard’s more famous Garden City proposal by a decade. Rather than merely “throwing off a planetary system of satellite communities,” Soria y Mata’s Ciudad was meant to ruralize the urban and urbanize the rural by linking congested city centers to their hinterlands, decanting the former while conveying “the hygenic conditions of country life to the great capital cities.” Resembling a giant fishbone, his extruded city was structured about “a single street of 500 metres’ width,” in and about which would be “trains and trams, conduits for water, gas and electricity, reservoirs, gardens and, at intervals, buildings for different municipal services.” The Ciudad could be extended ad infinitum, to “Cadiz and St. Petersburg, or Peking and Brussels,” and would resolve “almost all the complex problems that are produced by the massive populations of our urban life.” In the 1890s Soria y Mata launched a series of ventures to turn his vision into reality, among them a publication, La Ciudad Lineal, that soon evolved into the world’s first city-planning journal. A short segment of linear city was eventually built in the suburbs northeast of Madrid, along a boulevard now named Calle de Arturo Soria.30

The great prophet of the linear city in America was an Alabama-born inventor named Edgar Chambless. Employed as a patent investigator in New York and reflecting on the flotsam of bad ideas he was forced to sift through, Chambless began “to dream of new conditions”—specifically, of a metropolis that might work a lot better if it were extruded outward into the countryside. “The idea occurred to me,” he wrote in 1910, “to lay the modern skyscraper on its side and run the elevators and the pipes and the wires horizontally instead of vertically . . . I had invented Roadtown.”

I would build my city out into the country. I would take the apartment house and all its conveniences and comforts out among the farms by the aid of wires, pipes and of rapid and noiseless transportation. I would extend the blotch of human habitations called cities out in radiating lines. I would surround the city worker with the trees and grass and woods and meadows and the farmer with all the advantages of city life.

Chambless spent the rest of his life searching for a place and a patron to build this “earthscaper.” He was a forceful missionary, converting skeptics by the score and even convincing Thomas Edison to donate his patent for cast-in-place concrete houses (admittedly not one of his better ideas). Chambless self-published a treatise in 1910, Roadtown, a cult classic today among infrastructure junkies (its shortest chapter, “The Servant Problem in Roadtown,” is but a single sentence: “There will be no servant problem in Roadtown, as there will be no need for servants”). Julian Hawthorne, in the book’s foreword, predicted that—like the biblical Moses—Chambless would “lead us out of our long Egyptian bondage” to urban congestion. The New York Times gave the book two glowing reviews, noting that Roadtown would not only be “fire, cyclone, and earthquake proof,” but likely do away with “most of the inconveniences of city life, including noise, dust, smoke, streets, horses, trusts, graft, and city employees.” Shoppers that fall found generous renderings of “the queer, snakelike metropolis” in store windows all over Manhattan.31

Illustration from the cover of Edgar Chambless, Roadtown, 1910.

Chambless found his ablest evangelist in Milo Hastings, a polymath social reformer and inventor who patented, among other things, a forced-air egg incubator and a health-food snack for children called Weeniwinks. Close friends and onetime roommates, Chambless and Hastings collaborated on several ventures. In December 1916, the latter penned a lengthy tract in the Sun proposing Roadtown as the solution to the “blight” caused by the textile industry’s incursion into the Fifth Avenue shopping district. He envisioned a great linear Garment City along Newtown Creek, joined to Manhattan via the IRT line (today’s 7 train) and extending from Hunters Point Avenue across two hundred acres of vacant “factory flat land . . . where the dead sunflowers now protrude through the untrodden snow.” To this production-line metropolis “the makers of clothes may move,” wrote Hastings, “and by moving may save both New York and themselves.” It could be made high or low, adorned with parks or plazas, configured in a hundred ways—giving “city planners . . . real creative work and not merely a chance to bewail the mistakes of the fathers and to patch expensively that which has been wrongly made by a petty and individualistic generation.” It was during the Depression that Chambless came closest to realizing his linear city dream. In March 1933, the Times and other news outlets reported that federal officials were seriously considering a roadtown between Baltimore and Washington, and even assigned staff from the Emergency Work Bureau to draw up plans. But Rexford Tugwell’s Resettlement Administration chose instead a more conservative alternative for the satellite town of Greenbelt, Maryland. Chambless also nearly convinced the World’s Fair Corporation to adopt a linear layout for the fair’s Flushing site. The back-to-back rejections broke Chambless, now widowed, ill, and living in a rooming house on West Forty-Ninth Street (across, ironically, from that icon of nonlinearity, Rockefeller Center). On a Sunday morning in May 1936 he came home from church, stuck a tube in his mouth, and turned on the gas; “the Roadtown Man” was dead.32

Around the same time federal planners were weighing a Baltimore and Washington linear city, Franco-Swiss architect Le Corbusier published a speculative scheme for the North African port city of Algiers that placed lineal urbanism squarely in the pantheon of the avant-garde. Conceived in protest of the French colonial government’s official plan, Corb’s Plan Obus was a radical departure from the beaux arts style favored by the regime (though it was just as tone-deaf to Algerian culture, customs, and local climate). It consisted of a monumental business district and civic center on the waterfront, a series of curving residential towers on the heights above the ancient Casbah, and—most memorably—a long serpentine expressway along the coast from which housing units for 180,000 workers were suspended in vast tiers. Corb had first toyed with linear city planning in a speculative scheme for Rio de Janeiro in 1929 and remained fascinated with its possibilities for the rest of his life. During World War II he developed plans for a “Cité Linéaire Industrielle” to solve the inefficiencies of scattered factory development by looking to imperatives of the assembly line—of “alignment, not dispersion”—as a model for modern industrial urbanism. Essentially a chic French edition of the homely Chambless-Hastings Garment City, it nonetheless kept the linear city flame alive long enough to make it back to New York City. At an evening convocation at Columbia University on April 28, 1961—part of a series of events honoring the founders of modern architecture—an aging Le Corbusier gave a speech “devoted exclusively to a presentation of his linear regional plan.” It is very likely that in the audience that night were at least some of the young dreamers who gathered about the court of John Lindsay’s Camelot.33

“Roadtown” as imagined by Popular Mechanics, December 1933, including school complex at lower right.

Plans for Linear City were trotted out in a swirl of publicity on February 25, 1967. Lindsay called it “a dramatic new concept for community development . . . a breakthrough of sweeping significance.” Planning commissioner Donald Elliott was confident that the Cross-Brooklyn Expressway would be substantially complete by 1973, while work on the project’s schools would begin within two years. The all-important air rights over the tracks would have to be negotiated from the Pennsylvania Railroad, but no one anticipated resistance from the faltering, cash-strapped company. Ten days later, Washington dumped cold water on all this vision making, doubtless to the great pleasure of Robert Moses. The Bushwick Expressway, though canceled by city and state, had never been officially removed from federal interstate highway system maps. Lindsay and his team assumed the Cross-Brooklyn Expressway could simply be substituted for the Bushwick. Officials at the Bureau of Public Roads promptly put the kibosh on such a swap; “the Cross-Brooklyn route,” spokesman Warner Siems informed Gotham, “was not an acceptable alternative.” Inclusion in the interstate highway network was vital, for then 90 percent of construction costs would be covered by Uncle Sam. The city, on the edge of fiscal disaster, couldn’t afford to build a goat path without a massive federal subsidy, let alone America’s first linear city. The bureau wanted a whole new proposal if it was to consider the Cross-Brooklyn Expressway at all. Nor were locals all that happy about the futuristic conurbation in their backyard. Lindsay had promised that Linear City would not be built without “continuing consultation” with residents in the affected area. But before the first meeting could be scheduled, howls of protest rose from all sides. Leading the charge was Bertram L. Podell—a Democratic assemblyman later charged with conspiracy (his trial put a young assistant US attorney named Rudolph W. Giuliani, an East Flatbush boy himself, on the front pages for the first time). Podell claimed that 1,042 residents would be displaced by the project (the Bushwick alignment would have dislodged nearly 4,000). “The people of Flatbush,” he vowed, “will not permit the Cross-Brooklyn Expressway to go through their homes.” And as for the proposed development atop the road, Podell suggested it be called “Carbon Monoxide City.” The Reverend Galamison, on the other hand, hitched his hopes to the scheme; “If linear city fails,” he said, “all hope for integration is lost.” Many in the local black community nonetheless feared that the huge project would be forced upon them without their input or consent.34

Lindsay and his team pressed on, quietly winning from federal authorities in April a pledge of partial support for the Cross-Brooklyn Expressway—50 percent of costs—if the route was officially added to the city’s arterial system. In a pyramid of Faustian bargains, Lindsay planned to take that pledge to the Tri-State Transportation Commission to beg inclusion of the route in the general highway plan for the metropolitan region. With that in hand he could go back to the Bureau of Public Roads to request reconsideration of the Cross-Brooklyn Expressway as part of the interstate network, thus making it eligible for federal funding. In August he secured a commitment from the state commissioner of education that the new schools planned for Flatlands, Brownsville, and East New York would be made part of Linear City, to include up to twenty thousand students. Excitement mounted for what could be the most progressive few miles of highway in the Western Hemisphere, if not the world. Ada Louise Huxtable, the city’s most admired architecture critic, admitted that while the dense urban core must be saved from ill-conceived renewal and expressway plans, it was also “a chamber of horrors for many” that called for bold action on the part of planners. “We need the roads,” she wrote; “We need the housing. We need the schools, the industry and the office buildings. But we do not need them in the conventional, city-destroying form that has forced so many thinking and feeling citizens to the barricades.” And the seeds of salvation, she pressed, might even be in the very things we fight. “In the superroad, the city-as-a-building, even in the gigantism that we have learned to dread and deplore, may be answers to our problems and challenging solutions to the modern urban dilemma.” Huxtable was unconvinced, however, that it could be pulled off. Money was not the issue, she reasoned, nor design or engineering know-how or construction technology. “The real problem is simple, and appalling,” she wrote; “In government everything is solidly stacked against getting anything done.” A project as vast in scale and scope as Linear City “must cut across all city departments and agencies. A design breakthrough is not enough. An administrative breakthrough is equally necessary.” And that, alas, would never come.35

By now, Lindsay had fully reversed his prior opposition to the Lower Manhattan Expressway—succumbing to pressure from the construction trade unions and presumably satisfied that, without the Bushwick Expressway, LOMEX would not be overwhelmed with traffic. In January 1967 he remarked that there was “no question that a high-speed multilane highway across lower Manhattan is necessary,” flatly contradicting a statement from his office only months before, that the project “never would be built in any form.” Fears had been eased in Little Italy by vague promises that the road would be fully underground. But tunneling under Manhattan proved too costly, and in early 1967 city engineers were directed to come up with an alternative plan using a combination of tunnels, open cuts, and surface roads. On March 7, 1968, the Board of Estimate approved the LOMEX project in a 16-to-6 vote. Lindsay called for the immediate construction of both LOMEX and the Cross-Brooklyn Expressway, hailing them both “key and indispensable” to the city’s future. A public hearing on LOMEX was then scheduled for April 10 at Seward Park High School on Grand Street. Purely pro forma, it had been hastily planned to evade pending legislation that would require a more rigorous community input process. State and city officials did not expect many attendees, nor did they count on the presence of one Jane Jacobs among them. In a turn of events now part of Gotham lore, a huge crowd packed the auditorium and grew restless as testifying speakers were summarily cut off for going over the time limit. The protesters began chanting, “We want Jane! We want Jane!” Jacobs rose from her seat, took the microphone, and warned that anarchy would be unleashed if construction of LOMEX went ahead. She then mounted the stage and called upon the crowd to join her. In the ensuing ruckus, the stenographer’s tapes spilled to the floor and were gleefully trampled and tossed about by the protesters. “Without the stenographic notes,” writes Anthony Flint in Wrestling with Moses, “the officials couldn’t prove they had satisfied the requirement to gather public input.” Grabbing the microphone again, Jacobs shouted, “Listen to this! There is no record! There is no hearing! We’re through with this phony, fink hearing!” She was promptly charged with disorderly conduct. “I couldn’t have been arrested for a better cause,” she later told a reporter.36

Paul Rudolph, linear city proposal for Lower Manhattan Expressway, 1970. Paul Rudolph Archive, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

But the torpedo had found its mark. Opposition to urban expressways of any sort was peaking in the city, an outcry that did not go unheard in Albany. By late April, the New York State Senate had passed legislation nixing the Cross-Brooklyn Expressway from state highway plans. With the bill making its way to the state assembly, Lindsay and Rockefeller made an end run around the legislators, convincing the state Department of Transportation to request inclusion of the Cross-Brooklyn road in the interstate highway system. When news of this broke, Representative Edna F. Kelly was outraged; a vocal opponent of the project, she accused state and city officials of brokering a clandestine deal that made a mockery of the democratic process. When asked about this, the mayor’s office simply responded, “We don’t know of any secret agreement.” The move paid off; for on June 28, 1968, three federal agencies—Transportation, Housing and Urban Development, and Health, Education, and Welfare—joined in an unprecedented multiparty endorsement of Linear City. Together they pooled several million dollars for studies of the necessary community and educational infrastructure, while the Cross-Brooklyn Expressway was at last made a formal part of the interstate highway system. The Ford Foundation chipped in, too, offering a $100,000 grant for further planning reports. To manage the increasingly complex project, a Linear City Development Corporation would be formed, with representatives from the City Planning Commission, Board of Education, Human Resources Administration, Housing and Development Administration, and both city and state transportation agencies—a herd of cats if ever there was one. Long a neglected backwater of Gotham, the southeastern corner of Brooklyn was poised to become the most prodded, poked, and overplanned place in the city. Linear City was so complex an enterprise, with so many moving parts, that a “Plan for Planning” was deemed necessary just to start. Produced by a youthful Baltimore firm later known as RTKL and featuring an elaborate system of hieroglyphs, three-dimensional “molecular” models abstracting the project anatomy, and piano-roll charts of dizzying complexity, it described Linear City as “an urban laboratory, radical in concept, massive in scale,” an experiment validated in its boldness and innovation by the “failure of existing social and physical institutions to adjust thus far to the volcanic forces that are shaking our society.” Even a “project historian” was called for, to record the evolution of Linear City from seed to completion, anticipated—incredibly—for 1975.37

Linear City would, in fact, never see the light of day. It died on a balmy Saturday afternoon in May 1969, as news of a fatal vote in Albany reached City Hall. State attorney general Lewis J. Lefkowitz had previously ruled that legislative approval was necessary for New York State to accept a federal offer to pay virtually the entire cost of the schools, community centers, libraries, parks, and playgrounds vital to Linear City. By now, Lindsay himself was having serious doubts about the project; just two months earlier he had quietly asked the Board of Education to build the planned Linear City schools elsewhere. The bill seeking approval for the federal funds passed in the state senate; legislators in the assembly, however, hadn’t forgotten Lindsay’s end run around them the year before. In a rush to vote just before adjournment on Friday, May 2, they voted down the reimbursement bill. Without Washington’s help, neither city nor state could ever afford to build all the infrastructure for Linear City, stripped of which the Cross-Brooklyn Expressway would be just another conduit out of town. Convinced its impacts would be “disastrous” to a part of town already severely stressed, Lindsay ordered an immediate halt to the entire project. The tea leaves were easy to read; the age of big urban highways was over. Desperate now for the support of liberal Democrats since losing the Republican primary in June, Lindsay scuttled the two big balls of asphalt chained to his political feet. On July 16, 1969, the mayor announced that both LOMEX and the Cross-Brooklyn Expressway were officially terminated—dead “for all time.” Thus a project once promised to unite the embattled, warring communities of southeastern Brooklyn did just that—it joined them in opposition. “I will not,” he vowed, “permit a swath of concrete to divide Brooklyn.” The summer of 1969 put Americans on the moon, the most complex and costly venture in human history. But it was also the summer of Stonewall and Woodstock, and a season of victory for the partisans of walkability and social justice and human-scaled cities. Just one week before Lindsay’s announcement, secretary of transportation John A. Volpe ended plans for the Vieux Carré Expressway that would have gutted the French Quarter, a project Moses had himself proposed twenty years earlier. America’s long day of urban highway building was over, and with it went Brooklyn’s star-crossed road of hope.38