EPILOGUE

UNDER A

TUNGSTEN SUN

Everything changes; the light of Brooklyn remains . . . long-shadowed horizontal light, revealer of form, Dutch light, the light of Vermeer, if you will, suffused with the presence of the sea, slanted, immanent, revealing.

—PETE HAMILL

Fred Trump razed the Pavilion of Fun just months after the last of Pennsylvania Station fell to the wrecking ball. The destruction of these icons—unprecedented acts of civic vandalism—formed an axis of loss that spanned the East River and seemed to augur troubled times to come. Most of the mighty train station—Gotham’s own Baths of Caracalla—came down in the very months that Steeplechase Park struggled through its final season, its immense granite columns carted off ingloriously to the Secaucus meadows shortly after the Funny Place closed for good in September 1964. A decade later, Brooklyn and the rest of New York City struck bottom. But even then—with muggings rampant, subway cars covered in graffiti, Son of Sam on the loose, and the city teetering on the brink of bankruptcy—a revival was well under way in parts of Brooklyn. Starting in the late 1960s, a trickle of college-educated, young, and mostly white progressives began moving to the borough, lured by the threadbare glory of once-aristocratic precincts like Park Slope and Brooklyn Heights. These children of Woodstock, straining against the status quo, relished the borough’s working-class grit. Like Carson McCullers and her February House fellow travelers a generation earlier, they found in Brooklyn’s seedy squalor the flowers of authentic urban culture—one that promised respite from the conformities of suburbia and the relentless consumerism of mainstream American society. Here was a place with everything Levittown lacked—a storied past, architectural splendor, racial diversity, down-to-earth folk more or less tolerant of nontraditional lifestyles.

The “brownstoners,” as they came to be known, stripped and scraped paint to expose brick walls and original wood trim, reveling in the grandeur of mansions reclaimed from rooming-house ignominy. They developed strong bonds with one another, which in time gelled into a potent political force. Well-organized, well-informed, charged with a Davidian zest to take on Modernity’s many Goliaths—highway builders, urban renewal authorities, city planners, city hall—the brownstoners helped institutionalize participatory democracy, neighborhood preservation, and local control of the planning process in New York City.1 Their patron saints were Rachel Carson, Betty Friedan, and—above all—Jane Jacobs, whose 1961 Death and Life of Great American Cities was a shot across the bow of the urban renewal juggernaut that, led by Robert Moses, had been tearing holes in the city’s physical and social fabric for decades.2 The brownstoners changed the map of Brooklyn, coining—with the eager assistance of realtors—evocative new names for the plebian hoods they colonized. Cobble Hill and Carroll Gardens were carved from the Italo-Rican vastness of South Brooklyn; the nebulous terroir between Atlantic Avenue and the Gowanus Canal was renamed Boerum Hill, where the newcomers displaced a small community of Mohawk ironworkers from upstate New York. The long-reviled Fifth Ward, a place nobody (my mother, for example) boasted of hailing from—was cleverly rebranded Vinegar Hill, a name from the 1830s when the area was an Irish enclave (recalling a key battle site in the Irish Rebellion of 1798). By 1981, the old manufacturing district next door had caught the eye of a developer named David Walentas, who saw in its vast, largely empty industrial lofts a real estate diamond in the rough. With financial backing from an unlikely source—the Estée Lauder family—Walentas went on a buying spree, snapping up eleven buildings with two million square feet of floor space for a mere $15 million. Most of this was the old Robert Gair Company complex, or “Gairville,” birthplace of the mass-produced cardboard box and later home to scores of manufacturers great and small—among them the Heyman Glass Company, where my grandfather worked as a cutter and polisher in Gair Building No. 6 (75 Front Street). Two decades after he first set foot on Fulton Landing, Walentas had single-handedly transformed the deserted industrial zone into America’s hottest new neighborhood—Dumbo, for Down Under the Manhattan Bridge Overpass. In 2017 the iconic clock-tower apartment in Gair Building No. 7 (1 Main Street)—a single unit—sold for the same sum that bought Walentas nearly a dozen buildings in 1982.3

By the early 1990s the gentrification of Brooklyn was officially under way, as creative-class professionals—eased out of Manhattan by skyrocketing rents—snapped up Brooklyn’s relatively affordable but rapidly escalating real estate. As the Heights, Park Slope, Fort Greene, and Dumbo all soon Manhattanized beyond the reach of all but the very wealthy, real estate refugees began settling in places farther afield, with progressively less architectural quality and fewer cultural amenities—cheaper, grittier, more “real” precincts far from the stroller-jogging yoga moms of overpriced Park Slope. This new generation of neo-bohemians—the aspiring actors and barista novelistas, but also worker bees of the emerging “symbolic economy”: software architects, web designers, sound engineers, bloggers and editors and other content-producing creatives—channeled (at least at first) much the same fiercely countercultural spirit that drove the brownstoners, even if they rejected their predecessors as old hippie sellouts. They appropriated (with due irony) a “white trash” aesthetic that has since become synonymous with hipsterdom: tattoos and facial hair, feed-store ball caps, flannel shirts, and truck-stop sunglasses. The coming of the hipsters, again mostly well-educated, white, and middle-class, signaled the closing of a great circle for Brooklyn—the return of a suburban bourgeoisie not, this time, to the rarefied brownstone districts of the long-vanished Anglo-Dutch elite, but to immigrant cradle neighborhoods from which some of their very grandparents had struggled to escape. “Symbolically, in their styles and attitudes,” writes Mark Grief, hipsters “seemed to announce that whiteness and capital were flowing back into the formerly impoverished city.” Their unrelenting search for the bloggably unique—handcrafted, local, organic, untainted by the filthy fingers of global capital—has, over the last twenty-five years, produced an almost comical succession of goods, services, and foods, each briefly curated by an über-cool hipster elite before diffusing to the masses as yet another must-have marker of membership, another stock item on sale at Urban Outfitters. For all their avowed animus toward mainstream culture, hipsters are aggressive shoppers. “The rebel consumer,” writes Grief, “is the person who, adopting the rhetoric but not the politics of the counterculture, convinces himself that buying the right mass products individualizes him as transgressive.” While any bohemian community has at its core “a very small number of hardworking writers, artists, or politicos,” it inevitably attracts a larger cohort of wannabes, emulators, and hangers-on. “Hipsterdom at its darkest,” writes Grief,

is something like bohemia without the revolutionary core. Among hipsters, the skills of hanging-on—trend-spotting, cool-hunting, plus handicraft skills—become the heroic practice. The most active participants sell something—customized brand-name jeans, airbrushed skateboards, the most special whiskey, the most retro sunglasses—and the more passive just buy it.4

More than anything, the hipster quest for cool has been about consuming place. First Williamsburg, then Bushwick and Greenpoint, later Bed-Stuy and Crown Heights—these once-shunned neighborhoods seemed to promise insider status for anyone moving there, entrée into a rarefied club of creative fellow travelers. In the process, Brooklyn has become both a product and a brand, one synonymous with the batch-made and the bespoke, the fixed-gear, fair-traded, and cruelty-free. That brand has now spread around the world—even to many of the very places from which immigrants once came in search of a better life.

Of course, the great irony of gentrification is that newcomers moving to an area for its character, charm, and individuality set into motion a concatenation of forces—economic, cultural, political—that ultimately destroy the very qualities that drew them to the place. Time and again, the unwitting agents of this upscaling are artists, writers, musicians, and other cash-poor creative types who colonize a place no one else seems to care or even know about and create—by their very presence alone—a “scene” that draws others with a ken for music and the arts. Before long come the galleries, cafés, and pop-up restaurants curated by visiting chefs. Next in are savvy developers like David Walentas, who buy up undervalued properties and turn them into luxury lofts for well-heeled professionals with jobs on Wall Street and Madison Avenue. By now, the penniless creatives who set the whole thing off are long gone. This unintended trend seeding is nothing new: it happened in Stockbridge in the Berkshires in the 1890s, Greenwich Village in the 1920s, and Brooklyn Heights in the 1940s. It’s what made Wellfleet and Provincetown sought-after summer spots, and what helped turn East Hampton—where Pollock, Motherwell, and de Kooning painted in shacks and Quonset huts—into the toniest place on the Atlantic Seaboard. Similar trajectories have reconfigured the Lower East Side, Tribeca, SoHo, and Chelsea, each now “a smooth, sleek replica of its former self,” writes Sharon Zukin, where chain-store banalities like Starbucks and Chipotle sit alongside wine bars with Montepulciano at $18 a glass.5

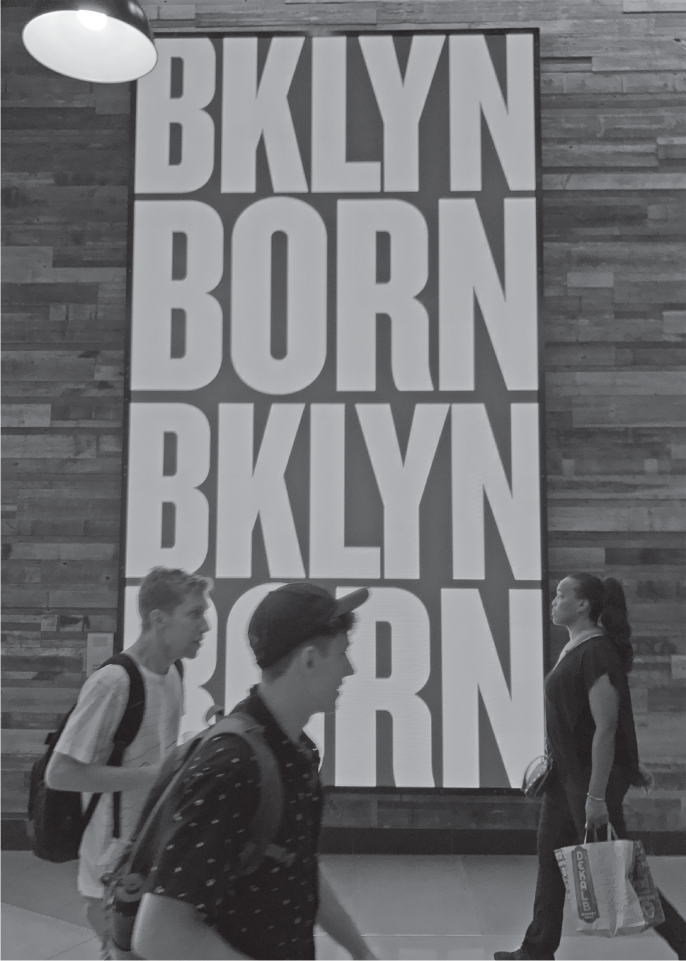

Once a badge of shame, now a point of pride: Brooklyn nativity gentrified at City Point, “largest food, shopping and entertainment destination in the borough.” Photograph by author, 2017.

The real motor of gentrification is contemporary society’s fevered quest for authenticity, a function of an unsettled, increasingly homogenized world in which all the old bulwarks—neighborhood, tribe, family, faith, nationality—have progressively weakened. “Claiming authenticity,” writes Zukin, “becomes prevalent at a time when identities are unstable and people are judged by their performance rather than by their history or innate character.” With everything in flux in a globalizing world, authenticity “differentiates a person, a product, or a group from its competitors,” conferring “an aura of moral superiority, a strategic advantage that each can use to its own benefit.” Today, people of privilege hunger for authenticity the way their class forebears yearned for status and luxury. Because most consumers are content with a simulacrum of the real thing (so long as the stage props are right), authenticity can easily be manufactured—“made up,” says Zukin, “of bits and pieces of cultural references: artfully painted graffiti on a shop window, sawdust on the floor of a music bar, an address in a gritty but not too thoroughly crime-ridden part of town.” However ersatz, these “fictional qualities of authenticity” have a genuine impact on our urban imaginary, and “a real effect as well on the new cafés, stores, and gentrified places where we like to live and shop.” In this sense, authenticity is hardly a neutral aesthetic but a political and economic weapon—a means of controlling “not just the look but the use of real urban places” like shopping streets, neighborhoods, parks, and community gardens. “Authenticity,” Zukin concludes, “is a cultural form of power over space that puts pressure on the city’s old working class and lower middle class, who can no longer afford to live or work there.” Gentrification kills the real McCoy to venerate its taxidermal remains.6

Truth may be greater than fiction, but in New York City today manufactured authenticity has rubbed out much of the thing itself. The search for character, color, and uniqueness has cost many a city neighborhood those very things—their essence, their identity, their soul. And the juggernaut shows no sign of slowing. As Manhattan morphs into an isle of the superrich, Brooklyn has become ground zero of gentrification in New York. Like an oil stain on a sheet of newsprint, its upscaled terrain has spread steadily over the last twenty-five years—down into Red Hook and Latino Sunset Park, now even Bay Ridge; south into Kensington and Ditmas Park; east across Crown Heights and even edging into the embattled neighborhoods of Brownsville and East New York. The leading edge of this gentrificant tide is difficult to pin down and requires an almost block-by-block analysis. On a summer evening in 2017, I attempted to do just this—took a break from working on this book to walk Flatbush Avenue from Fulton Street to my deep-south Brooklyn neighborhood of Marine Park. I was hoping to see the light, literally: the warm tungsten light of vintage Edison lightbulbs. I’ll confess a deep affection for these retro-style bulbs myself; nearly every room in our home is illuminated by their soft carbon glow, which seems particularly “period appropriate” for a house built in the 1920s. And I’m hardly alone in this. Many people have a penchant for these bulbs, or at least for bars and restaurants basked in their light. Walk around any upscaled part of New York City, and at least half the eating and drinking establishments will be sporting vintage lights in their pendants and chandeliers. My evening walk was meant to test a little hypothesis: that the spread of Edison bulbs across town was effectively a map of gentrification.

It’s hardly a coincidence that the Edison phenomenon has closely tracked the revival of urban living—especially the loft culture that blossomed in postindustrial districts like SoHo and Tribeca. After all, vintage tungsten-filament lamps (and their more recent, more sustainable LED equivalents) show best in spare industrial fixtures, not hidden behind a fussy lampshade. It was entrepreneur Bob Rosenzweig who helped ignite this lighting revolution in the 1980s, manufacturing reproduction vintage lightbulbs for collectors and museums. Sales were thin for years, until compact fluorescent (CFL) lamps began replacing incandescents on store shelves. By the mid-aughts, Rosenzweig’s bulbs had become all the rage with New York restaurant designers. Then came the 2007 Energy Independence and Security Act, which set new standards for energy consumption that effectively banned most incandescent bulbs. But there were exceptions—among them yellow bug lights, black lights, and “decoratives” such as Edison bulbs. Sales were also helped by the harsh blue-white light of the early CFLs, which could make the coziest home look like a morgue. The appearance or quality of a light source is a function of its color temperature. Measured in Kelvin—a thermodynamic temperature scale with a null point of absolute zero—color temperature is counterintuitive: the lower the temperature, the “warmer” a light appears, and vice versa. Natural daylight—a mixture of sunlight and skylight—runs from about 2,000K at sunrise or sunset to as high as 5,500K when the sun is directly overhead. The temperature of an ordinary incandescent bulb is about 2,700K, while that of a halogen lamp is around 3,000K and a cool-white compact florescent approximately 4,000K.

Tungsten and twee in Prospect-Lefferts Gardens. Photograph by Alyssa Loorya, 2017.

Most people find light of lower color temperature to be warm and intimate—the light of home and snug bistros on Old World streets. Much of this is hardwired in our brains, a function of deep ancestral memories of camp and cooking fires and the cycle of day and night. The high light of noon stimulates us; the autumnal glow of sunset eases us like a glass of wine. Culture, too, plays a role. In China, a brightly lit home was long associated with wealth and luck (demons lurked in dark corners, flushed out with fireworks at Lunar New Year). That illumination was both a status symbol and a ward against evil helps explains why brightly lighted shops and restaurants are still common in China. Most Westerners (and younger Chinese) favor low dim light in a restaurant—light that evokes the ambience of a candlelit dinner. It is no coincidence that the gossamer tungsten glow of an Edison lightbulb delivers a color temperature almost identical to the romantic light of a candle flame. The retro lights are today accurate markers of the upmarket consumerscape, signaling the presence of creative-class tribal space. They offer seeming respite from the buzzing glow of our digital screens, retreat to a curated version of an earlier, simpler, more earnest age. And with our streets increasingly amped up with intense LED light—Brooklyn was the first New York City borough to have its amber sodium-vapor streetlights replaced by LED units—it’s hardly surprising that we expect our bars and cafés to provide shelter from the light storm outside.

Brooklyn’s original Main Street, Flatbush Avenue, makes a ten-mile plunge from downtown Brooklyn to Floyd Bennett Field. The route has long formed an unspoken boundary between Brooklyn’s majority black neighborhoods of Bedford-Stuyvesant, Crown Heights, and East Flatbush, which lie to its east, and the mostly white enclaves of Park Slope, Ditmas Park, and Midwood to its west. My summer evening stroll revealed two dense concentrations of Edison-lit establishments on the avenue. The first, not surprisingly, lay between Grand Army Plaza and Atlantic Avenue, where Flatbush runs past affluent Park Slope. There was a second burst of incandescence from Empire Boulevard to Caton Avenue—in the more recently upscaled neighborhood of Prospect-Lefferts Gardens (where Greenlight Bookstore is the only non-religious bookstore on Flatbush Avenue south of Prospect Park. My observed density of Edison bulbs, it turns out, aligned precisely with data compiled on real estate heat maps of residential property valuation and listing prices. Areas with the highest concentrations of tungsten were reliably deep within or on the edges of neighborhoods with very expensive housing. In fact, they mapped closely to market valuations of a million dollars or more. Once listing prices dropped below seven digits, at about Beverley Road, the lights disappeared. The last tungsten-bulbed establishment was close by, Forever Ink Bar, at the corner of Duryea Place near the recently restored Kings Theater. This is effectively the outermost line of gentrification in Brooklyn: the lights go out, so to speak, just as white people with plugged earlobes and yoga pants also vanish. From here Flatbush then becomes a teeming bazaar with an island patois, Main Street of one of the largest West Indian communities in the world outside the Caribbean. From Forever Ink to Avenue U (a three-mile run, or nearly half my walk), I found not a single Edison bulb—none in the hundreds of West Indian shops and eateries; none by Brooklyn College; none in the busy blocks through Orthodox Midwood; none as the avenue glides expansively across the quiet residential terrain of Flatlands and Marine Park. It was as if I had tripped an invisible cultural switch.7

Fluorescent authenticity, Island Buffet, Flatbush Avenue. Photograph by Alyssa Loorya, 2017.

Here lies one of the great truths of urban life today, not only in Brooklyn but in gentrifying cities around the world: the truly authentic lies far from the places that claim it most insistently—far from the historic districts with their pious, exclusionary rules about architectural minutiae; from boutiques with all things fair-traded and bespoke; from restaurants with curated chervil and house-made catsup where only the rich can eat. If you seek the real New York, flee the twee and you will have found the city in all its brassy bravado, its loud messy magical heartfelt glory. Look, in other words, beyond the warm light of vintage tungsten (or sustainable LED equivalents) to the cold white glare of coiled CFLs and ceiling-mounted fluorescent tubes—in the Guyanese grills and Dominican bodegas, the Hasidic shuls and African American storefront churches that rock with gospel on Sunday; in the Bangladeshi newsstand or the Chinese take-out with its kitchen-god temple—the harsh unflinching light of reality in our town, where life is still lived unposed and uncurated and close to the bone.