Chapter 1

1910s–1920s

The November morning was brisk, bright and promising, so I went underground.

It was not a protest against beautiful autumn days but a long-overdue, first visit to the National World War I Museum—a sleek twenty-first-century bunker beneath the 1920s-era Liberty Memorial.

Therein I saw spiked helmets, colorful tunics and hand grenades of many nations. I stood in a scale-model shell crater amid recreated sounds of battle. I read maps, timelines and charts of numbers upon numbers. I watched short films with ominous soundtracks. It was a blend of antique and high tech working hard to distill and animate years of events that snuffed an old world and birthed a new one. Even spread out over three hours, it was pretty overwhelming.

So I rode the elevator up and back, about ninety years, to the observation deck of the Liberty Memorial.

When the war ended in the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month of 1918, people here had already been talking for two days about the Kansas City Journal’s idea.

“The most practical and most happy suggestion for perpetuating the glorious achievements of the Kansas City, and Missouri and Kansas soldiers,” the newspaper called it. “Erect a Victory monument in the station plaza.”

Detail of a frieze by Edmond Amateis on the north wall of Liberty Memorial. Courtesy of the author.

Civic leaders reacted: “A splendid idea indeed.” “A glorious way for the people of Kansas City to express their appreciation of the soldier boys.” “Let’s not talk about it, but go right ahead and provide the monument.” “What a grand thing it would be to do.”

And there was another thread of thought: “It would beautify the city,” said the Journal.

“The victory arch at dawn, the victory arch at noontime, in winter, in spring, in the fall, the victory arch at sundown, at midnight—what a pleasure for Kansas City and a privilege to gaze at its ever-changing beauty.”

The architect of the city boulevard system took it another step. It was time to move beyond a preoccupation with commerce—it was time for art.

“I believe the memorial is but the beginning of further effort along the line of great civic enterprises,” said George Kessler. “We are beginning to learn that there is another phase of life besides that of accumulating.”

Funds for the monument came from private donations. The entire $2.5 million was raised in ten days.

The thing that now loops in my memory of the war museum is the audio alcove: a glassed-in cone of silence with softly colored lights and a sound system that plays snippets of old speeches, music and literature. It delivered that old world to me more immediately than any timeline or ersatz shell hole.

A keypad touch brought the voices of the kaiser and President Wilson; songs like “How ‘Ya Gonna Keep ’Em Down on the Farm (After They’ve Seen Paree?)”; and excerpts from A Farewell to Arms and The Great Gatsby. There was also “In Flanders’ Fields,” the poem written by Lieutenant Colonel John McCrae, a Canadian who never it made it home from the war; I played that one twice.

It was a poem my schoolgirl mother memorized in the 1940s, when schoolchildren did such things. November 11 was called Armistice Day and veterans of that war—some missing an arm or a leg—sold carnations on street corners. The other day on the telephone, Mom proved she hadn’t forgotten the verse that begins: “In Flanders Fields the poppies blow / Between the crosses row on row.”

The November sun was shining up on the Liberty Memorial observation deck. With its commanding view of the city, this has long been an island of peace and a quiet place to reflect about lots of things: about the ironies of a war to end all wars; the poetry in thousands of poppies at the museum entrance and the lighted “torch” atop the memorial’s two-hundred-foot tower; the fact that fewer travelers now first see this place from Union Station than from speeding cars on the section of Interstate 35 that slices through downtown; or the enduring, ever-changing beauty of the monument. As a war memorial, it is a source of civic pride and a portal to a younger city— awakening to a new phase of life.

Sixteen hundred miles west of Union Station in the Los Angeles suburb of Monrovia, just off the Foothills Freeway, past the Wal-Mart and the Home Depot, inside the leafy and spacious confines of Live Oak Cemetery lies a headstone that reads: “Fritz E. Peterson, 1892–1931, 110 Engineers 35 Div.”

It marks the final resting place for an Army veteran who returned home to Kansas City from the Great War and heard California calling him to become a chicken rancher.

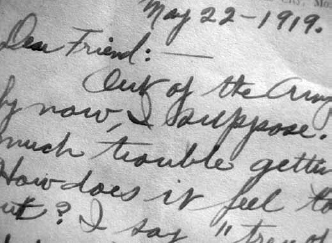

Fritz Peterson’s postcard. Courtesy of the author.

The 110th Engineers were maintenance workers. They dug trenches, built shelters, cleared battlefields and did other manual labor for the 35th Division of the American Expeditionary Forces in France during the summer and fall of 1918.

The Thirty-fifth Division saw only five days of action, in late September, in the Argonne Forest. In five days, the division advanced more than six miles, captured more than seven hundred Germans and suffered more than six thousand casualties, including more than a thousand dead. There’s a story about a group of engineers working in the field who, attacked by Germans, fought with picks and shovels until their armed comrades arrived.

The 110th seems a natural place for Fritz Peterson to have landed after being drafted in 1917. His father was a maintenance engineer for the Kansas State School for the Blind in Kansas City, Kansas.

The Great War had its own language. Tank, camouflage, dogfight, dud and no man’s land are terms that survive. Less remembered, perhaps, are to swing the lead, which means to malinger; to go west, which means to die; and some slang terms based on mispronunciations of French words, such as toot sweet from “tout de suite” and tray beans from “tres bien,” To American doughboys, a Fritz was a German soldier. That must have made life interesting for Fritz Peterson.

They came home in late April and early May 1919, those men of the Thirty-fifth Division, most from Missouri and Kansas. Full trains pulled into Union Station, sometimes with casualties and many missing arms or legs, in which case they would stop for Red Cross ladies to board with food and cigarettes, and then they would continue to convalescent hospitals somewhere. More often, the trains unloaded soldiers who would parade down Main Street to celebrate at downtown hotels, and then they would head back to the station for the last few miles to Camp Funston and a discharge.

A few weeks later, one of them wrote a message on a picture postcard of Union Station and addressed it to Chicago:

Dear Friend,

Out of the Army and home by now, I suppose. Have much trouble getting out? How does it feel to be out? I say “tray of beans.” Ha! Ha! I may go west.

Best regards,

Fritz E. Peterson

It’s one of those industrial landscapes—in this case, a concrete-and-razor-wire parking lot—that has swallowed whole blocks between the Crossroads and Historic Jazz Districts. No street signs exist here, but this used to be the intersection of Nineteenth and Tracy.

The area is so bleak that it’s difficult to imagine anyone using the corner’s bus stop, which is a vestige of the streetcars that stopped in front of the school that once stood here. On maps, it was sometimes identified as “Lincoln High School (Colored).”

Lincoln High was a predecessor of today’s Lincoln Prep Academy, which sits on the hill at Twenty-first and Woodland. Actually, the old Lincoln curriculum was preparatory, as well. Students took classes in science, history and English literature. In the vocational-training department, they learned sewing, automobile repair, carpentry and bricklaying. Lincoln was well-known for music education.

Alumni included Walter Page, who played the upright string bass, later founded the Blue Devils and eventually became part of the famed rhythm section in Count Basie’s Orchestra; and Charlie Parker, who used an alto saxophone to change the future of jazz.

Sidewalk detail at the corner Nineteenth and Tracy. Courtesy of the author.

The class of 1920 included Maceo Birch, who became a local entertainment promoter, later the road manager for the Basie Orchestra and eventually the head of the Negro band department at MCA records.

The summer before Maceo’s senior year had been especially bad for lynchings in America; more than seventy were reported. During the school year, a black man was shot to death by a mob 140 miles east of Lincoln High in a small Missouri town. Another was hanged by a mob 120 miles south in a small Kansas town.

Here in Kansas City that year, children at an all-white elementary school put on a play, The Pied Piper of Hamelin. The play had a black character whose lines included: “But chile! Yo’ should hab seen dem rats when dat Massa Pied Piper come in dis ar town. Da’ followed dat man just like a lot o’ white trash after a hunk o’ lasses taffy.”

At an all-white high school, the play was a comedy titled Alabama. A reviewer remarked of one character: “No one would ever have thought that George Pratt could make such a good ‘nigger’ as Decatur until he saw ’Alabama.’ George’s wobbly legs and ‘nigger talk’ brought much laughter from the audience.”

At Lincoln, seniors reported their life ambitions to the school yearbook. Maceo Birch said he wanted “to own and operate a sporting goods store.” For others it was to be a nurse; a milliner; an expert typist; an athlete second to none; a great businessman; or a first-class contractor, cornetist, cook, stenographer or dentist. They also aspired to be a bantamweight champion prizefighter, chief cook for Fred Harvey, cartoonist for the New York Tribune, leading soprano in Tolson’s Jubilee Concert Company or president of Petty Business College. Others wanted to become a lawyer, oil magnate, drum major in a great band, vamp, old maid or Mrs. Miller. And some hoped to teach English at Wilberforce, travel with Bradford’s band, have a fancy art shop on Petticoat Lane, own a first-class garage on Vine Street or live as royal as a king.

Under the bus-stop sign at Nineteenth and Tracy lies an old suggestion: a remnant of sidewalk and some brick pavers, cracked and broken. In 1920, Lincoln High was a handsome brick building. It’s not known whether any member of the class of 1920, in his or her heart of hearts, ever imagined being sworn in as the president of the United States.

What is known is that the class colors were old rose and white; its flower was the sweet pea; and the class motto was Vestigia nulla retrorsum— no steps backward.

Down at the corner of Fourteenth and Main, where intensely bright lights turn night into day, the gray stone façade and celery-green dome of the new-old Mainstreet Theatre appear handsomely 1921, even as its marquee and innards are now brilliantly twenty-first century.

My favorite detail is the throwback sign—vertical lettering encircled by lights that rise like bubbles in a flute of champagne—which erases time, leaping over the shuttered years, over the Empire and RKO Missouri years to the period between the world wars.

The 1921 Mainstreet was the work of Rapp & Rapp architects of Chicago, who were responsible for theaters in more than twenty American cities, including the Paramount in New York and the Chicago in Chicago.

The Mainstreet Theater’s effervescent sign. Courtesy of the author.

Today, their Mainstreet facade is a shell for a state-of-the-art, six-screen movie complex.

The original theater was built by the Orpheum theater circuit for the live spectacle of vaudeville—comedy skits, song-and-dance teams, animal acts, acrobats and jugglers—four times a day, as well as for movies, or “photoplays.” It had 3,200 seats, an elevator, a motorized movable stage, plenty of restrooms and telephone booths, and lower levels housed an elephant cage, a seal pool and a nursery for small children. It was the largest theater in town, and it was bigger than its big brother on Baltimore, the Orpheum, which catered to a high-class, reserved-seat, subscriber-type audience.

The Mainstreet was intended for the masses, with open seating and continuous shows from noon to 11:00 p.m. It was perfect for businessmen on lunch hour, travelers killing time between trains and mothers shopping downtown with their children. Mom could drop Junior in the blue-and-white nursery while she caught the show.

Junior would find wooden blocks and stuffed animals, a rocking horse and a row of small wicker chairs, all white except for a single blue one, which he would of course choose. When he sat in it, music would play, and when he got up to investigate, the music would stop. His puzzlement provided endless amusement for the adults in attendance.

The Mainstreet’s opening day in 1921 aligned with the arrival in Kansas City of Vice President Calvin Coolidge, the World War Allied commanders and tens of thousands of war veterans assembling that week for the national American Legion convention and the dedication of the Liberty Memorial.

Hordes of them found their way to the new theater at Fourteenth and Main, seeing a show headlined by Eddie Foy and the Younger Foys. The bill included a comedienne, singers and dancers, bicycle riders, a dog-and-pony-and-monkey act and two brothers in blackface, advertised as “Impersonators of the Southern Negro.” The photoplay feature was After Midnight, starring Conway Tearle.

The end of the original Mainstreet came at 3:20 one afternoon in early 1942, when the owners gave refunds to audience members and closed up. “Circumstances beyond our control,” they said. The last live act to play under the Mainstreet signage was the Duke Ellington Orchestra.

Forty-some years later, when the theater was known as the Empire, the last movie I saw there was The Cotton Club. It was about the famous New York jazz club during the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s, when the resident band was the Duke Ellington Orchestra.

Surely at least one Junior is still alive somewhere. I’d like to bring him down to see this new Mainstreet in its sleek Power & Light District setting and put him at a table in the gracious soul-food establishment upstairs across the street, at a window overlooking the theater’s effervescent retro sign.

There, he might ponder the distance between his plate of catfish with collard greens and the old Mainstreet’s blackface Impersonators of the Southern Negro.

And he might finally free his younger self from that haunting blue chair.

People once lived where Penn Valley Community College now sprawls. In the 1920s, apartments studded the south side of Thirty-first Street near Pennsylvania; modest buildings like those still found all over town that include three floors, two flats per floor and balconies overlooking the street.

Three floors, two flats per floor and balconies. Courtesy of the author.

When a man stepped from one of those apartment buildings on the morning of December 4, 1922, reporters from the local dailies were there with questions.

“I have nothing to say,” said the man, whose name was Frank Warren. “It is nobody’s business anyway.”

Inside, the newsmen were met by the lady of the home, Mrs. Mary Warren, and her two houseguests that had just arrived from England, Miss Nancy Jordan, age twenty-three, and her two-year-old son, Francis.

“Men believe women to have a feline nature—that women are consumed with the desire to scratch and claw at other women,” said Mrs. Warren, the thirty-one-year-old former wife of Frank Warren.

“We will be much happier when everyone forgets about us.”

This is what Mary Warren and Nancy Jordan insisted was true:

Frank Warren, a U.S. Army lieutenant, had met Nancy Jordan, a bookkeeper, in post-war London in 1919. A friendship developed, and some months later, Miss Jordan gave birth to a boy. The father was an English soldier named John Smith, who disappeared.

Frank, hearing of Miss Jordan’s situation, wrote about it in a letter to Mary, his wife of nine years. Mary, moved by the story, began a correspondence with the troubled young woman.

After Frank returned home to Kansas City, he and Mary divorced. It was the upshot of longtime incompatibility. Frank, an attorney at a fledgling downtown law firm, moved in with his mother. Mary, who came from money and had her own business interests, took the apartment on Thirty-first. They remained good friends; the divorce had nothing to do with Nancy Jordan or her son, Francis.

Mrs. Warren offered to pay passage to the United States for the unwed mother and child and to give them a temporary home in her apartment. Miss Jordan, fearing her situation would bring torment to her son if they remained in England, accepted.

Nancy said: “Mrs. Warren now says she will adopt my little boy and give me a place by her hearthstone. Was ever such ennobling altruism between two women?”

Mary: “It isn’t altruism on my part. I simply want to do all I can for that little boy. I want to give him a home.”

Frank: “Miss Jordan, herself, says I am not the father. If I were to say the child is mine, I would be challenging the truth of Miss Jordan’s statement. Personally, I do not care what people say or what they think.”

Upon arrival in New York, mother and son were detained at Ellis Island. Without a sponsor to assure they would not become public charges, they would be deported. Mary traveled to New York, paid a five-hundred-dollar- bond each and brought them home to Kansas City. Frank met them at Union Station.

Up here on Thirty-first Street, the 1922 view has changed. Instead of high-rise luxury condos, Mary Warren looked out on the St. Joseph’s Orphan Home for girls. In place of the Firefighters Fountain, Nancy Jordan saw only the woodsy sweep of Penn Valley Park.

“It is so beautiful here—so very beautiful,” Nancy said that December morning, which was her first in Kansas City.

One wonders what was said after reporters left, what expectations existed. There was Mary: dark haired, tall and slender in her rose-colored morning robe. And there was Nancy: small and pretty and fair-haired in a white housedress. Young Francis played with a new Teddy bear. His wide-set blue eyes matched those of his mother. His brown hair did not.

By the end of the next summer, Nancy Jordan was ready to return to London. Altruism had ended after the first week, and Mary Warren had remarried and moved away.

“I found there was no place for me,” Nancy told reporters. “I felt that I could not afford to let myself and my child become a burden upon anyone.”

She said she left the Thirty-first Street apartment, got a job and placed Francis in a foster home. Then she talked about the boy’s father.

“Anyone can see the resemblance of Francis to Mr. Warren,” she said. “I have letters at home in England in which Mr. Warren assured me we would be married in this country. If for no other reason than to give my child his name.”

The father’s support payments had dwindled over time, she said. And he had been urging her to give up Francis for adoption.

Frank said: “I have nothing to say. I don’t care to reopen this case again, for anything I might say would not matter now.”

Then a message for Nancy arrived at the Kansas City Journal from an Englishman in Chicago who had met her on the voyage to New York and followed her story in the papers: “Will you marry me and stay in America? Where can I see you? Wire answer.”

Three days later, Nancy Jordan agreed to become Mrs. Claude Heatherington Clarke.

The groom said: “This has been the greatest day of my life. Kansas City is a great town.”

Francis: “I’m going to have a new daddy!”

Nancy: “I thought all my love was wrapped up in my boy, Francis, but I was wrong. I’m sure now my heart is big enough for them both.”

The northeast corner of Tenth and Grand is a chilly place. The old Federal Reserve Bank building—awaiting a new high-end, residential life—looms there, empty and imposing. Bulky planters and other security obstacles crowd the sidewalk needlessly now, since the bank has moved to new headquarters near the Liberty Memorial.

Still, it retains an oversize beauty and the elegance of a 1920s institutional structure. Six two-story pillars at the entrance are flanked by two allegorical bas-relief panels by Henry Hering: Spirit of Industry, with its sheaf of wheat and distaff, and Spirit of Commerce, with its torch of progress and caduceus of Mercury. Hering was known for his institutional sculptures in other cities, including Cleveland and Chicago.

Detail of Henry Hering’s Spirit of Commerce on the old Federal Reserve Bank at Tenth and Grand. Courtesy of the author.

You might imagine a visiting Chicagoan could feel almost at home on this corner.

One October Saturday in 1923, a middle-aged lawyer named George W. Pennington left his Dearborn Street office in Chicago, bound for a meeting at the Title and Trust Building around the corner on Washington Street. It was normally a two-minute walk. The day was fair in the Windy City, but somewhere on his walk, George W. Pennington entered a tunnel of fog and vanished.

At dawn four days later, a ground-hugging cloud slid into downtown Kansas City and snaked southward, eventually stretching from the Missouri River to Twenty-eighth Street, swirling and blending with smoke from factories and coal-burning locomotives.

From morning sunshine, commuters plunged into a dark soup of auto horns, streetcar bells and sightless pedestrians. Traffic crept along streets, arriving trains stopped short of the Union Station sheds because of switching delays. Gradually, the pale disc of the sun warmed and dissolved the cloud, revealing abandoned autos and a streetscape familiar to most Kansas Citians.

On one downtown street, a well-dressed, middle-aged man blinked as if awakening from sleep. He saw things he’d never seen before.

That was not the Title and Trust Building he knew.

A block uphill—(hills?)—he asked a policeman about that large, pillared building on the corner.

It’s the Federal Reserve Bank, said the cop, who wore a strange badge.

And this street corner?

Tenth and Grand.

No. That can’t be right. There’s no Tenth and Grand in Chicago.

Overhead, Spirit of Commerce smiled knowingly. She had stone-faced cousins in Chicago.

The bewildered man sat in the matron’s room of the Nineteenth Street Police Station. Papers in his pocket identified him as George W. Pennington of the Chicago law firm of LeBosky and Pennington. Associates and relatives were en route to Kansas City to retrieve him.

He said this was his third memory lapse in several months since that taxicab accident. He recalled leaving the office to go to a meeting at the Title and Trust.

“I don’t remember riding a train,” he said. “In ten minutes, it seemed, Chicago had turned into hills and valleys and strange buildings.

“Nice town here, but too many hills and strange buildings.”

I’m driving east on Independence Avenue, the ethnically diverse business thoroughfare in the Northeast neighborhood. Just past Benton Boulevard, traffic bottlenecks around a small pack of police cruisers huddled at the intersection of Indiana Street. At least one man is handcuffed and sitting on the sidewalk there.

As I squeeze past the Super Pollo Restaurante on the corner, I can see the 600 block of Indiana, a rather forlorn street of two-story residences in various stages of neglect. It’s not clear that aesthetics and property values are neighborhood concerns.

At least, not by 1924 standards.

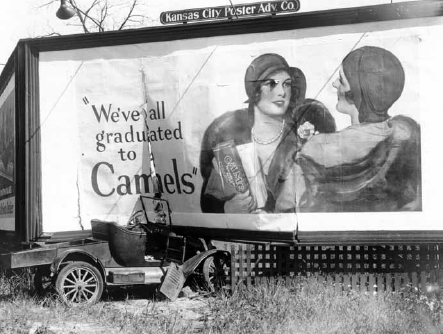

Billboards had long been an issue. Courtesy of Missouri Valley Special Collections, Kansas City Public Library, Kansas City, Missouri.

The Super Pollo occupies the former site of a vacant lot. In the spring of 1924, the lot was a sort of guerilla garden, an improvised neighborhood park in which several new flowerbeds in various shapes—squares, triangles and hearts—had been spaded and seeded by one man. T.H. Moore, who ran a small grocery next door on Independence Avenue, also planned benches for his garden. Neighbors called him “the park board.”

People expected eventual construction on the vacant lot, and one day that April some men appeared with lumber. Stomping through T.H. Moore’s flowerbeds, they dug holes and sank wooden posts. Surely this was the beginning of a new shop to join the cobblers, barbers, plumbers and others along Independence Avenue. Such was the common wisdom.

That is until one Friday when men returned with more lumber and began framing the posts. And then neighbors realized this was the start of a three-panel advertising billboard.

Billboards—and their perceived blight—had long been an issue in Kansas City. The city’s official policy was to try to control them by refusing to issue permits, but hundreds had gone up around town anyway. Many had gone up in recent weeks, perhaps in anticipation of the new mayoral administration.

Someone telephoned downtown and talked to the city’s building superintendent. No permit had been issued for a billboard, and the lot’s owner, who lived in Florida, had no knowledge of any construction.

That evening, after the workmen had left, people gathered in T.H. Moore’s little park. Some brought hammers; others wielded loose boards. As they worked and the crowd applauded, a representative of the Thomas Cusack Company arrived and demanded they stop tearing down the company’s sign. The neighbors drove him away.

“It is a detriment to our property, lowers its value and is a menace to the welfare of the community,” said one.

On Saturday, the workers returned and rebuilt the framing. They added one new feature: notice of a fifty-dollar reward for helping convict anyone destroying the sign. And that night, four company men stood watch.

On Sunday, ten miles away near the southern city limits, another crowd gathered in the name of neighborhood pride. This was suburbia—the new Armour Hills development—and the occasion was the dedication of a new fountain in a grassy island near Sixty-ninth Street and Wornall Road.

It was to be the focal point of the planned Armour Center: a cluster of shops, a movie theater, a filling station and a church situated near the new station along the Country Club streetcar line. There were new trees, honeysuckle, and ivy-covered stone walls, which were all part of the developer’s commitment to the protection of property values.

The fountain, a piece of white Venetian marble commissioned by the developer, J.C. Nichols, depicted an American eagle and two children. The sculpture, said the Nichols Company, symbolized the American home, as Armour Hills “typifies true patriotism and home life.”

It was “not only for the residents of Armour Hills but for all Kansas Citians who love the beautiful.”

Hundreds of Kansas Citians who loved the beautiful gathered that night at the corner of Independence and Indiana. About a dozen carried axes and saws and attacked the rebuilt billboard with renewed vigor. The sign company’s guards were nowhere to be seen.

Piece by piece, the sign became a pile lumber; cans of oil and kerosene appeared. Just before the match was struck, a final piece was flung to the top of the pile: the fifty-dollar reward notice.

A neighbor said, with certainty, “If they put that structure back up we’re going to burn it down again.”

Wheeling south, I drive the ten miles from Independence Avenue to Sixty-ninth and Wornall and pull over near a small grassy neighborhood park and its marble fountain.

People walk and jog where streetcars once ran; houses sit where the Armour Center would have been had not early residents voiced concern about what shops would do to their property values; and the Venetian-marble eagle and children have been replaced by a different, aquatic-themed sculpture, something not obviously symbolic of anything more than neighborhood splendor. The only sound is a single lawnmower—the droning harbinger of summer.

It makes me think of a long-forgotten vacant lot across town and what might have been: a bench, a heart-shaped flowerbed, maybe some hollyhocks.

It was a ticket stub, about one inch by an inch and a half, a remnant of some New Year’s Eve in the orchestra section at the Orpheum. December 31 fell on a Thursday, but what year? An Orpheum Theater operated in the 1200 block of Baltimore from 1914 until it was torn down in 1962, so I took a stroll through some of the possible Thursdays.

Tonight at the Orpheum, celebrate with a Vaudeville revue starring long-legged Charlotte Greenwood, the sensational comedy hit of the season.

Elsewhere, hotels and clubs have reservations for six thousand at $6 to $15 per couple for dinner and dancing to Tike Kearney’s Arcadians or the Shadowland Serenaders. Horns and funny hats are included, not to mention a detective, a government man and a tabletop sign reading: “The reservations made for New Year’s Eve in this room were with the strict understanding that there would be no violation of the liquor laws.” Although the local bootleg is said to be hair tonic and perfume with some of the blindness boiled out, a quart of gin will cost $4 and a case of whiskey will run you $175.

Streets will fill with ladies in evening gowns and orchid corsages, and men in tuxedos and silk mufflers and black derbies. Just before midnight, steam locomotives and factories will open their whistles in the wintry cold, joining claxons and sirens across town. In the Pompeian Room, Father Time will shuffle out—a large clock will open to reveal a dancing 1926. In the traffic crawl at Twelfth and Main, taxi drivers will backfire their motors. Revelers will cling to the tops of buses, tooting paper horns. One car will carry a full orchestra. Two young men in dinner jackets will hand out keys to the city. A gray-haired man will speak to a young woman in a green dress with a drunken escort: “Lady I don’t know you and your friend but I gotta car and it’s going your way.”

A remnant of some New Year’s Eve. Courtesy of the author.

Tonight at the Orpheum, celebrate with the Woodward Players in As Husbands Go, a comedy about two women from Dubuque who travel to Europe and contemplate divorce.

Elsewhere, Jack Collins and his Eleven Rhythm Aces will play “Snappy Music” at the Aladdin Hotel Roof Garden, and there’ll be “Beautiful Girls, Plenty of Favors and Plenty of Surprises.” The White House Tavern will offer Walter Page and his Thirteen Blue Devils, and a “Delicious Breakfast” after 5:00 a.m. Dance 9:00 p.m. to 5:00 a.m. at El Torreon, with “Two Bands For this Big Whoopee Occasion!” At Nichols, expect a “Hotsy Totsy Time, a Good Floor and a Red-Hot Orchestra.” And Chic’s Fourteen Pla-Mors will play the Pla-Mor Ballroom from 10:00 p.m. until 4:00 a.m. The Pla-Mor promises “Thousands Will Greet 1932 Prosperity!”

Partygoers will pay a five-dollar cover. A woman will lose her diamond-and-sapphire wristwatch. Police will raid a man’s home, arrest him and confiscate three and a half pints of liquor. Just before midnight, revelers and autos will choke the junction of Twelfth and Main with autos backfiring, drivers hollering and doorway merchants hawking paper hats and noisemakers at reduced prices. Cops will blow whistles; someone will fire shots in the cold night air; boozy rumble-seat riders will wave and shout at the sidewalks: “Happy near you! ’Pressions shover!”

Tonight at the Orpheum, celebrate with “The Show You’ll Talk About Long After You’ve Stopped Laughing!” Cary Grant and Ginger Rogers star in Once Upon a Honeymoon. “Extra Special! Walt Disney’s Donald Duck in Der Fuehrer’s Face.”

Elsewhere, thousands will flock to parties at Municipal Auditorium, the Hotel President, the Phillips, the Muehlebach and the Continental or to Milton’s Tap Room, where Julia Lee is at the piano. There’s also the Folly Burlesque for the Silk Stocking Revue; and the Tower Theater for Billy Rose’s Diamond Horseshoe Revue, with Gilda Gray, “the Queen of the Shimmy,” and “America’s Most Beautiful Girls.” Special streetcar and bus service will run until 3:00 a.m.

Police will block traffic along Twelfth Street. Thousands will be wearing the olive drab or navy blue of the armed services. They’ll be dancing at the Canteen, streaming in and out of the Officer’s Club, nibbling doughnuts at the USO, standing three deep at the Cabana Room bar and cajoling civilians for a bottle when MPs shut off their alcohol at 9 o’clock. Just before midnight in the Terrace Grill, an old man will drag a scythe out of the way of a bouncing baby dressed as 1943. A soldier and a sailor will stand up and the crowd will sing “Auld Lang Syne” and “Praise the Lord and Pass the Ammunition” and the national anthem.

Outside, the mild night air will fill with confetti, whistles, horns and firecrackers. Celebrants in Hawaiian leis and paper hats will stop to pet a pair of white puppies for sale and toot horns at them. Five soldiers will surround a girl in a blue coat, pass her from one to the next and steal kisses. A young civilian will grab a passing servicewoman and strong-arm her and shout at the night: “Whooee! I always wanted to kiss a WAC!”

Tonight at the Orpheum, celebrate with “The First Sweeping Adventure Entertainment In Cinemascope” with King of the Khyber Rifles, starring Tyrone Power.

Elsewhere, dance till 5:00 a.m. to the Red Hot Scamps at the Mayfair Club. Enjoy the “Keyboard Varieties of David Chody” at the Zephyr Room; Scotty Lynn on organ in the Zanzibar Room; Dusty Williams and his Boys at the Tick-Tock Lounge; Cliff Sheperd and his Ozark Crest Riders at the Rainbow Club; and Gus DeWeerdt, “Famous TV Entertainer,” at Sans Souci. “No Reservations Necessary. No Cover Charge, No Tax, No Minimum.”

Just before midnight, thousands will pour from hotel lobbies and clubs and cars, bound for Twelfth and Main, a blend of light jackets and military uniforms and black ties and gardenia corsages. The mild night air will carry the bleat of toy horns, the rattle of cowbells and the pop of balloons and fireworks. Confetti will be tossed; women will be kissed; and teenage boys will scuffle. A gray-haired man will ask four cops to dance with him in the street. Shortly after midnight, the crowd will melt away. Down at Union Station, people in cone hats amid a forest of balloons will hear loudspeakers crackle: “Attention please: the Kansas City Terminal Railway Company wishes you a happy new year for 1954.”

The mezzanine of downtown’s Hotel President is not exactly as it was when the hotel opened in early February 1926—the recent total renovation did not bring back the shops and beauty parlor; the library with its stock of the latest fiction by Sinclair Lewis, F. Scott Fitzgerald and Edgar Rice Burroughs; or the WDAF radio studio that piped popular tunes to all 453 guest rooms.

Still, the ornate chandelier and fluted columns say 1926, and from the mezzanine railing it’s not hard to see a tall, slender Irishman in a dark blue suit, gray tie, plaid silk socks, brown oxfords and gray homburg striding across the marble floor of the lobby one morning in late March of that year, heading for the elevators.

“That’s him,” says an excited bellboy. “That’s Big Tim!”

Timothy D. “Big Tim” Murphy has arrived, fresh from three years in the Leavenworth slammer.

At that point, Big Tim’s resume included newsboy in Chicago’s stockyards district, gang leader, Illinois legislator, union boss, racketeer and convicted felon. This last distinction stemmed from a $360,000 mail robbery at Chicago’s Dearborn Station in 1921. As mastermind, he was sentenced by Judge Kennesaw Mountain Landis to six years in Leavenworth. With an appeal and time off for good behavior, he served only three, adding to his resume the duties of pipe fitter in the prison power plant.

The Hotel President. Courtesy of the author.

Kansas City hadn’t figured much in Big Tim’s original plans. His wife, Flo, had been visiting him from Chicago every two weeks during his prison time. But she disliked the bathtubs in a Leavenworth hotel so she’d been staying in Kansas City and hiring a taxi to drive the sixty-mile round trip so she could see Big Tim.

Flo and a traveling companion were waiting in the taxi parked outside the penitentiary gate at 6 o’clock that morning of his release, having already delivered new clothes to her husband the day before. He refused the suit the prison provided all freed prisoners, as well as breakfast and the free ride.

“Get on away,” said Big Tim, in his new duds, to the guard at the gate. “You stink. Damn that hell-hole and everyone in it.”

Then he turned to reporters. “I’ll be in Kansas City until tonight,” he said. “Look me up there if you’ve got anything to say or ask, but I don’t want to waste a lot of time ‘cause the missus and I have some visiting to do.”

In those pre-Drum Room days of Prohibition, the President had a drug store at its corner of Fourteenth and Baltimore and a separate lobby entrance on Fourteenth. That’s the one the Murphy entourage used that Friday morning, and they immediately went up to Mrs. Murphy’s suite of rooms on the ninth floor and ordered breakfast.

The plan was to board an overnight train for Chicago later in the day. But Big Tim learned authorities planned to greet him upon arrival with an arrest warrant. It was something about a $10,000 fine levied with his conviction that he had yet to pay. Since there was to be a band, banners and a bunch of Big Tim’s pals there to welcome him home, an arrest would be humiliating. He decided to extend his stay in Kansas City.

So Friday and Saturday, Big Tim held court in suite 941 to 943, talking with reporters, receiving friends and talking on the telephone. He said he wanted to get back to Chicago and see his mother and his nieces and nephews, go horseback riding and travel to Europe with his wife.

“I want to get back to my old job of fighting for the men and women who do the work of the world,” he said. “I’ve been doing that for twenty years, and I expect to keep at it until I die.”

On Sunday morning, he sent his wife home on the train to run interference on the arrest business. Then that night, he boarded a Santa Fe train for Chicago, saying he had decided to “go ahead and get it over with.”

I like to imagine Big Tim up in his suite on the ninth floor, late on a Kansas City Saturday night, stretched out on the sofa under the portrait of President Calvin Coolidge, listening to the radio broadcast from down in the mezzanine studio. WDAF’s Nighthawk Frolic, tunes of the day drifting out of a tinny speaker—maybe Ben Bernie’s “Sweet Georgia Brown” or Vernon Dalhart’s “The Prisoner’s Song.”

Now if I had wings like an an-gel

O-ver these pri-son walls I would fly

And I’d fly to the arms of my poor dar-lin’

And there I’d be wil-ling to die

When he arrived in Chicago, Big Tim Murphy was not arrested.

Two years later on a warm night in late June, he answered the doorbell of his bungalow on Chicago’s far north side. No one was there, but a car with curtained windows pulled up and a machine gun put an end to Big Tim. His murder was never solved.

The tracks under the Main Street viaduct near Union Station carry heavy traffic, primarily freight. Two passenger trains run back and forth daily to St. Louis, and another stops once in each direction traveling between Chicago and Los Angeles.

It’s a long way from the years when a person standing on the viaduct could watch hundreds of passenger trains pull under the sheds every day, and from the September morning when hundreds of people lined the railing, waiting for one particular train from the east.

On the day he died, in the summer of 1926, the thirty-one-year-old man born Rudolph Guglielmi was on horseback with a beautiful woman, riding into a desert sunset in downtown Kansas City.

Patrons of the Royal Theater sat that afternoon in the flickering light of The Son of the Sheik, dabbing eyes with handkerchiefs. “Doesn’t it almost frighten you to think that he is dead and we see him moving before us on the screen?” said one.

Tracks under the Main Street viaduct. Courtesy of the author.

Outside on Main Street newsboys sang out their early editions: “All about the death of Rudolph Valentino!”

In those days before antibiotics, Valentino succumbed to infection after surgery for appendicitis and a gastric ulcer. In New York to promote The Son of the Sheik, he was stricken in a hotel room and spent his last week in a hospital room, surrounded by flowers.

Police struggled to control tens of thousands who assaulted the Manhattan funeral parlor in the rain to get a two-second glimpse of him in an open casket. Plate glass windows shattered; shoes littered the streets; and women fainted.

Those who knew him characterized him as a great artist; a flame of genius; an excellent actor and a fine fellow; a very dear friend and a man of charm and kindliness; one of the screen’s greatest lovers, but one of Hollywood’s most perfect gentlemen; honest and sincere; a real man.

“I felt somehow that such a brave, intense living spirit could not die,” said one actress.

A Hindu mystic declared that anyone on the proper spiritual plane knew only the body was gone. “If he was beautiful, it was his soul,” said the mystic. “And it lives, so why all the mourning?”

Like most movie stars, Rudolph Valentino had spent time in Kansas City, if for no other reason than that the transcontinental train he was riding had an hour-or-so layover at Union Station.

On one such stop not long before his death, a local reporter had found Valentino sullen and withdrawn as he wandered the cavernous lobby of the station, hands in pockets, hat pulled down low, ignoring women who recognized and approached him. Finding refuge outside in the parking lot, he complained.

“I hate to be seen in public. They’ve made me rich, but they’ve made me miserable,” he said. “I’d lick anybody, or let them lick me to prove that I’m a man. I’m tired of being the sheik. I’m tired of the whole business.”

The reporter decided the source of irritation was an editorial in a Chicago newspaper. The editorial had blamed Valentino for subverting American masculinity, calling him a “pink powder puff.”

At 10:30 a.m. on September 4, twelve days after Valentino died, the Rock Island Railroad’s Golden State Limited chuffed slowly toward the Union Station train sheds on track 14, its steam locomotive stopping just under the Main Street viaduct. Maybe fifty onlookers peered down from the railing on Main. The public had been banned from track level, but several people ran along the platform anyway.

Between the dark engine and its regular consist were two special cars. The first bore Valentino’s body in its solid bronze casket with sterling-silver overlay and a fresh array of lilies, delphiniums, gladioli, palms and pink and yellow roses. The second carried an entourage of intimates, including his brother, his manager, and his lover, screen actress Pola Negri.

Messengers carried a few telegrams to the train. A bystander offered five dollars for the chance to deliver them to Pola. Inside her drawing room, the black-haired Pola sent a telegram to her chauffeur in Los Angeles, ordering a blanket of pink roses for the casket, seven feet by three. She looked as if she had been crying for twelve days. She wore a black robe over peach silk pajamas and black-satin slippers and held a large photograph of Valentino. Her chin trembled; her voice was weak.

“My grief does not permit me to speak at any length,” she said. “There was never a formal engagement. There was no date set. It was just an understanding arising from a beautiful friendship.”

The brother announced he was changing his name to Alberto Guglielmi Valentino. The manager said final funeral arrangements were pending. Up in the station lobby, some young flappers were asked whether they were trying to see the Valentino train.

“Heck no,” said one. “My sweetie’s coming in on the 11:10.”

It was said that Valentino had intended to stop awhile in Kansas City on his return from New York to Hollywood. Apparently he believed he had done a disservice on some previous visit.

“I made a mistake, and the best way to rectify a mistake is to ask to be forgiven,” he was quoted as saying. “I want to stop there long enough to meet the people and try to make them like me.”

At 11:20 that morning, the Golden State Limited inched out of Union Station and headed west. Up on the Main Street viaduct, the crowd of fifty had become three hundred—plus the lingering soul of a man hoping to be forgiven.

Perhaps he was recognized by anyone on the proper spiritual plane.

The corner of Twenty-second and Grand lies wedged between the contemporary glass and steel of Crown Center and the rejuvenated brick of the Crossroads District. Years ago, you could stand on this corner and see Union Station and the rows of train sheds that sheltered arriving and departing passenger trains. The train sheds are long gone, and a large office building now blocks the view of the station.

Across the street, along the edge of Washington Square Park, a sidewalk running west toward Liberty Memorial and the train station hugs a concrete balustrade above the rail yards. Surely it’s the same path walked by that woman and her six children on the first day of 1927.

There was a streetcar stop here on Grand for the Rockhill–Northeast line. The woman and her kids, all under the age of twelve, waited here. When a maroon streetcar rattled along, the seven of them climbed aboard. It was a fair New Years Day, with temperatures in the forties.

She told the conductor she had no money; she said they’d spent the night on benches in Union Station after riding a train to Kansas City, which was as far as her funds would take them. Someone at the Travelers Aid booth told her to take this streetcar to the Jefferson Home for Women and Children, on Garfield Street, and wait there for money to be wired.

A sidewalk runs west toward Liberty Memorial. Courtesy of the author.

She was trying to get to her parents’ home in Kansas. A week before, at Christmas, her husband had abandoned them.

A headline on a small story in the next day’s Journal-Post made the conductor a hero. The story told of him paying the family’s fares and then passing a hat among the streetcar’s thirty passengers. At a time when a loaf of bread cost a dime and a pound of beef cost forty cents, the passengers put six dollars in the hat.

Later that day, money arrived from the woman’s parents, and the family continued the journey home.

Standing here now at Twenty-second and Grand, I’m thinking of a particular passenger on that streetcar, “an elderly woman,” in the newspaper account. I see her listening to the conductor explain the situation. She looks at the faces of the children and then at the mother. Maybe she stares out the window and down this sidewalk that leads to the train station. Maybe she’s imagining herself in a tough situation like this—or remembering one.

The story said she put $1.50 in the conductor’s hat. It was all she had in her purse.

A springtime Kansas City thunderstorm can be simultaneously frightening and fascinating. Downtown offers its rooftops and hilltops as ideal places to watch a distant thunderhead build, blacken and blow into town, flashing its lights and dragging curtains of wind and rain across the city.

Typically, it arrives from the southwest in the afternoon, with the warming of the sun. But weather here can be ornery.

And so, with rain streaking my windows and Randy Newman’s “Louisiana 1927” in my head, I’m thinking of the day a cloud, maybe four miles high, billowed out of the northeast just after dawn.

The spring of 1927 had been a wet one in Kansas City, maybe five inches beyond average. But the rivers were normal and it was nothing like what they were getting down south and east, where rain had been falling since the previous summer.

Weather here can be ornery. Courtesy of the author.

It seemed every morning the papers told of some new break in the levees along the lower Mississippi, more people lost, thousands more homeless in refugee camps or, worse, clinging to treetops or the roofs of house–islands in a raging brown sea. There was rain and more rain, wind and hailstorms breaking windows of every house in some little Arkansas town or flattening a wheat field and drifting two feet deep in Oklahoma. Kansas City got nothing like that.

And there was nothing surprising about waking up here under a cloud on May 7, a Saturday—just another workday morning for most. About a quarter to 8:00, the sky darkened. Lights came on in houses and apartments; motorists switched on headlights. People at breakfast glanced down at the newspaper’s forecast: “Unsettled weather…a possibility of light showers.”

The air was perfectly still. The cloud opened. The water fell heavily.

On the ground, it gathered itself, rushed to the nearest gutters, swelled into widening streams and climbed curbs onto sidewalks. Businessmen waded ashore from streetcars, carrying stenographers to the higher ground of corner drugstores.

It spilled into basements, knocking out electric power and shutting down elevators. Carts in the City Market toppled; radishes trailed in the wakes of tomatoes.

It scoured the streets, lifting old wooden paving bricks from their sand beds, sending them bobbing along Main and onto the running boards of cars parked in the Union Station plaza, which had become a lake that greeted arriving passengers.

It raged down Walnut, choking storm drains, eddying in muscular circles and halting traffic. It overtook the intersection of Thirteenth and Jackson with ten feet of water, creating a two-block logjam of streetcars with anxious faces at the windows.

In ten minutes—from 8:20 to 8:30 a.m.—one inch of rain; another inch and a half fell by just after noon. As it lessened, storm drains caught up, and the water slowly receded. An underground torrent headed for the river.

Out east near the Sheffield Steel plant, three construction laborers hurried to remove two pumps from a new sewer project on the Blue River. The river was rising and they could hear a roar building in the huge sewer, but they felt protected by a temporary dam.

When the wall of water hit, the dam broke. The three men were swept into the river. Two grabbed floating lumber and struggled to shore. The third, a twenty-nine-year-old newlywed named Albert Stewart, was hit in the head by a collapsing scaffold and disappeared under the surface.

That May, tornadoes and straight winds killed dozens and blew down houses and barns in Missouri, Kansas, Arkansas, Texas, Indiana, and Michigan. An earthquake on the New Madrid fault rattled towns in several states. Heavy snows blocked roads on the high plains. In June, a comet passed close to the earth.

In August, a member of the Adventists declared, “Recent cyclones, bad storms, volcanoes, eruptions, falling meteors and political turmoil indicated the approaching end of the world.”

The bloated lower Mississippi and its tributaries pulled back from Arkansas, Mississippi and Louisiana. Then, in late September, the rains returned to Kansas City. In one weekend, nearly six inches fell and the Blue River ran over its banks. Thousands of people rode out to Swope Park to watch trains—engines snorting steam—plow through standing water.

Downstream, the Missouri surrendered the remains of Albert Stewart, still clad in his leather jacket and raincoat.

Now, listening to “Louisiana 1927” or some delta blues like “High Water Everywhere,” I might imagine Albert Stewart is returning to town, as if his spirit had continued down the Missouri into the swollen Mississippi and south, maybe a week’s journey to the delta, some more days to Louisiana and on to the gulf, mingling and melding along the way with spirits— officially 250 dead, but there were surely more buried in the mud—of all those washed away.

The dog and I were walking along a stretch of brick storefronts on Seventeenth Street. A white truck, double-parked, delivered crisp linens to a vegetarian cafe with bud-vase flowers in the window. At the corner of Summit, an athletic blonde in lime-green shorts jogged slowly past more boutique food, past modest Victorian houses and a sleek new home of concrete-and-glass design, past weeds and rosebushes and past a scruffy guy draining water from a fishing boat on a trailer.

A breeze carried the sound of metal on metal: battered hubcaps and other silvery junk hanging from a chain-link fence along with animal bones and smiling ceramic heads. Next door was a deserted, yellow-brick school— West Junior High—its stately windows sealed with plywood; it is not a place that inspires celebration now. But one summer evening in 1928, when this neighborhood was known as the “Mexican colony,” the school auditorium hummed with life and the celebration of Mexican independence.

It was September 16, the 118th anniversary of the cry of Don Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla of Dolores, who rang his church bell and urged his followers to revolt against the Spanish colonists: “My children, a new dispensation comes to us today. Will you receive it? Will you free yourselves?”

This day, they gathered on the hill at Twentieth and Holly Streets in Observation Park. There was a parade with floats decorated in red and white and green, with a king and queen cheered by revelers in shawls, brightly colored skirts, embroidered vests and straw sombreros. They sang the Mexican and American national anthems. A stringed orchestra played. There were footraces and boxing matches and speeches, tamales and enchiladas and ice cream cones. And there was the revered host, Dr. Nicholas Jaime, the community’s mentor, greeting celebrants with a cheerful “Buenos dias!”

West Junior High School. Courtesy of the author.

The Mexican colony had existed since at least 1911, after the start of the Mexican revolution, when the first extended family arrived. Dr. Jaime came three years later, in time for the influx of immigrants after the world war when the number grew to thousands. He had attended the University of Michigan and the University of Illinois medical school, and then he headed a Mexico City hospital. He landed here when visiting a friend who asked him to treat a sick person.

“Then I stayed on a few more days, looked over the Mexican situation here,” he remembered later. “And seeing the need of medical attention in the colony, I decided here was my life’s work.”

At the time, many immigrants were living in poor, unsanitary conditions in overcrowded shacks or damp basements. They worked in packing plants or rail yards, had unskilled jobs or no jobs at all. Most were illiterate and spoke no English. No clinics or churches would accept them.

With others, Dr. Jaime had worked over the years to improve their quality of life. Now there were churches and health clinics, Boy Scouts and Camp Fire groups and a community center with classes in homemaking and in reading and writing English.

“If we can make good Mexican citizens, we can make good American citizens,” said the doctor.

From Observation Park, the celebration moved to the auditorium of West Junior High at Twentieth and Summit Streets. A stringed orchestra played; people danced; and more speeches were made. Then, Dr. Nicholas Jaime got up; he looked around at the people in their colorful costumes, and he must have felt satisfaction at how far they had come.

He knew there was work ahead—and difficulty—but he could not have foreseen the stock-market crash a year later or the long, hard times that followed. The great loss of jobs and the political turmoil that would lead to hundreds of thousands of Mexicans—including many U.S. citizens—being shipped back to Mexico.

Whatever lay ahead, he knew what he wanted to tell these people that night. Speaking in his native language, he urged parents to put their children in public school and for the adults to attend night school. The only way to a better life was through education and hard work, he said.

It was Independence Day, and the spirit of Don Hidalgo filled the auditorium of West Junior High. My children, will you receive it? Will you free yourselves?

Things are mostly quiet these days down at the former City Police Station no. 4 in the Crossroads District, once better known as the Nineteenth Street Station, which was a stop on the beat of a young Kansas City Star reporter named Ernest Hemingway.

The two-story, triangle-shaped building, built in 1915, got a partial makeover a while back in anticipation of becoming a Cuban-themed nightclub. The club never opened, but the ornate exterior—stucco with Craftsman-style woodwork—still wears the yellow and scarlet paint. Columns frame the old entrance, which is now home of the Hemingway Gallery, and in the early years they surely welcomed a variety of characters—usually the two-legged variety.

So the cops were probably as unprepared as anyone in town on July 24, 1928, as they were booking a man for drunkenness at the second-floor desk and a bellowing Hereford steer charged up the stairs from the street and plunged into the room. It was after midnight in Kansas City.

The former City Police Station no. 4. Courtesy of the author.

Five miles south, near Sixtieth and Oak in Brookside, a man awoke, looked out a window and saw a large animal standing in his flowerbed. It appeared to be a cow.

At dawn a man left his east-side home to begin his newspaper delivery route. If not for the fox terrier chasing two white-faced steers down Cleveland Avenue, it might have been the start of a forgettable summer Tuesday.

The Kansas City Stockyards once sprawled over more than two hundred acres between Twelfth and Twenty-third Streets, straddling the state line in the West Bottoms. The temporary home to thousands of mostly doomed animals, at one time they comprised a mud-and-wood labyrinth of 4,200 cattle pens, 700 hog pens, 400 sheep pens and chutes connecting the pens to railroad platforms and to big packinghouses with chimneys that belched foul-smelling smoke into the wind and across town. Fifteen large barns held mules and horses for buyers to examine. And for the buyers and the cowboys who worked the pens, there were hotels, offices, cafes, harness shops and banks. It was almost a city within a city, second in size only to Chicago’s stockyards.

Thousands of animals arrived daily from farms and ranches throughout the Plains and Southwest, sometimes as many as 30,000 to 40,000 cattle in a single day. One day, during World War II, brought 57,642 head of cattle to the stockyards for sale to buyers from around the country. Often there were several varieties: slender, shorthaired cattle from near the Gulf of Mexico; large, red, longhaired cattle from Montana; and white-faced Herefords from Kansas and Missouri.

In 1928, more than 8,000,000 animals funneled through the Kansas City Stockyards. Nearly 2,000,000 of those were cattle. Of those, some 150 Hereford steers and heifers were selected one July day by a buyer from Ohio and loaded onto four cars of an eighty-two-car Santa Fe freight train. Around midnight, the train pulled out and crept slowly east through town.

Just past the McGee Street Viaduct, a faulty switch derailed the locomotive. A second engine at the rear of the train shoved nine of the cars into a pileup, including three cattle cars. The cars broke apart and eighteen animals were killed. The terrified, wailing others blinked into the darkness and lit out in all directions.

The cattle scattered from Merriam to east Kansas City, from the river to Brookside. Human reaction varied.

Men in a parking garage at Twelfth and Oak stood well back and tried to coax a steer before he broke through a glass door, gored several automobiles and crashed through a plate-glass window. A crowd chased an animal into a bookstore at Eighth and Grand, where he knocked over bookshelves before running back into the street. A streetcar operator stopped his machine and examined a twisted bumper after hitting a steer at Thirteenth and Main. The steer got to his feet and trotted down Thirteenth.

The drunk at the Nineteenth Street Station fell to the floor as the charging animal ran past him, scattering furniture and policemen, and out another door. Out at Sixtieth and Oak, the Brookside man hopped into his Ford, revving the engine and honking the horn at the beast in his flowerbed.

A man, newly arrived from Alabama, saw another steer chasing people through Parade Park at Fifteenth and the Paseo. He grabbed for its horns, twisted its thick neck and rode it to the ground. A policeman helped tie the animal to a tree.

A pair of stockyards cowboys on horseback lassoed several auto bumpers before finally roping two animals near Twenty-ninth and Benton Boulevard. More cowboys corralled a small herd near the sphinxes at Liberty Memorial. Crowds surrounded exhausted animals tied to sidewalk poles at Sixth and Delaware and at Twelfth and Baltimore outside the Hotel Muehlebach.

Amid screams, the night agent at Union Station followed one creature into the women’s waiting room. Chasing it back into the lobby, he took hold of the horns, twisted and let the slippery, polished marble floors do the rest.

“I’ve been out West,” he told a red cap.

The roundup took a couple days, as did the cleanup down on the railroad tracks. The freight train also had been carrying butchered beef, eggs and fruit. Onlookers stood on the McGee Viaduct and watched a derrick lift the damaged locomotive and boxcars. Even then, the onlookers must have represented both viewpoints:

Those who in coming years would look at the stockyards and know what developer J.C. Nichols meant when he said there wouldn’t have been a Country Club Plaza if not for the livestock industry.

And those who would only wish the mud, the stink and that image would go away. The image that would cause, for instance, a New York reporter to wonder in print, “Why would anyone voluntarily visit a place once called ’the capital of cowtowns?’”

They’re the ones who would one day stand on the downtown bluffs and look out over the wide-open, odorless spaces of the West Bottoms and feel no loss.

I was standing at a Crown Center bus stop in the latest of several early winter snowfalls, wondering whether this was something like life in, say, Saskatoon (known to Canadians as Paris of the Prairies). Conversations around town had been variations on a theme: Someone had been in Kansas City for X number of years and had never seen winter like this. Forecasters had the mercury plunging toward zero and beyond, with a howling wind.

There were no complaints at the bus stop. The snow hushed the rush-hour traffic. White lights shimmered in bare branches. A Zamboni machine refreshed the nearby ice rink for skaters. A few stylish pedestrians were dressed for October, while most others wore layers of foul-weather gear. The electronic sign announced a delay for the MAX bus.

“Another will come along eventually,” said one cheerful, bulky woman in the shelter.

I waited outside, gathering snowflakes like a statue, drifting past Saskatoon to a January in Kansas City before wind-chill factors, road salt or four-wheel drive.

It’s a week past your New Year’s Eve celebration, when you were perhaps warmly toasting 1929 with a glass of bootleg hooch while outside it was snowing four inches.

Henry Merwin Shrady’s Valley Forge at Washington Square Park. Courtesy of the author.

Now the forecaster says there’s a bigger storm, blasting across the Plains out of the mountains. There will be rain first and then freezing temperatures, heavy snow—much colder; perhaps negative five with a sharp wind. And sure enough, it’s snowing plenty, maybe seven inches atop a layer of ice and old snow, and it’s blowing and drifting.

If you’re a homeowner, make sure you’ve got coal for the furnace. Maybe some of that Farmer’s Red Label, Cherokee Lump or Missouri Nut, which all cost $5.25 to $7.50 a ton.

If you’re walking, ladies, snap on your galoshes. Men, your old Army leggings from the world war will keep snow off your trousers.

If you’re driving, chop the ice from your driveway so those hinged garage doors will swing open; tighten those chains, or they’ll wrap themselves around your axle or flap and knock out your taillights; and good luck with those snowdrifts in the street.

If you’re taking public transportation, hope for the best. Streetcars with plows are clearing some tracks; eight hundred men are shoveling others, just in time for passing autos to repack them. Streetcars are backed up all over town, stalled on the ASB Bridge and the Intercity Viaduct, holding up interurban trains from St. Joseph and Lawrence. Buses, rerouted around slippery hills, fare better.

If you’re a long-distance traveler, your bus is blocked by snowbound highways, or your train, already delayed by the ten-state storm, now idles in the yards while hundreds of shovelers uncover the switches.

If you’re out for fun—no school because it’s Saturday—take your sled to any of several hilly streets barricaded for “coasting.” Beware of angry truckers; some drive through the barriers. If you’re a young woman in the Polar Bear Club, put on your swimsuit and play leapfrog in the snow. Still own one of those old horse-drawn sleighs? Jingle its bells out along the boulevards. Got a toboggan? Tow the neighbors around town behind your Ford.

If you’re a Boy Scout, put out crumbs or suet for the birds. “A few crumbs may save a song for next spring,” says executive scoutmaster H. Roe Bartle.

If you’re homeless, get to the hotel at Sixth and Main. It has a storeroom where you can escape the cold, get a sandwich and stand up all night with four hundred others. The Helping Hand Institute offers shelter and a job shoveling snow downtown. If you’re shoveling downtown snow, you’re one of five hundred men filling dump trucks and horse-drawn carts.

If you’re a nurse or doctor, you’re treating a broken wrist from a young motorist’s fight with a steering wheel and a snowdrift; a compound arm fracture from a man’s fall while chasing his hat, blown off after his car slid into a ditch; or a crushed hand, a lacerated head, a damaged eye—all from collisions of trucks with sleds.

If you’re a policeman, you’re getting calls from women who would like you to come start a car or shovel snow and bring in the newspaper. You think the weather is keeping crime in check.

You don’t believe it if you work in a filling station at Twenty-fifth and Paseo, where a man clomps in and says, “Cold night, isn’t it?” And when you agree, he says, “I hate to go out in it again” and flashes a gun and makes off with $87.64.

If you’re the Kansas City Public Service Company, take out a newspaper ad to apologize for the streetcar disruptions. Call it “the most severe snowstorm Kansas City has seen for years.”

If you’re just wandering, notice how snow changes park statues—a pillow of white for the baby in the arms of the Pioneer Mother or a look of wintry authenticity for George Washington on horseback at Valley Forge.

If you’re a dog, find a warm place to sleep inside the west entrance to Union Station, next to the radiators. People coming and going will stop to scratch your ears.

A MAX bus did finally arrive, followed closely by another. I boarded the one tinseled and draped with colored Christmas lights, full of bundled-up passengers and a driver in a leopard-print hat. We headed down Grand in the snowfall, passing city plows, a burly guy with a large umbrella and two Latino men shoveling downtown sidewalks.

Someone sitting behind me sounded resigned to the storm, but he was looking forward to a tropical thirty-degree forecast.

“We’ll be all right by Sunday,” he said.

Back in 1929, the forecaster is not so sure. He says, “A storm can be hatched up mighty suddenly this time of year.”