Chapter 2

1930s

The gravel road is now paved and lined with cars parked alongside the Internal Revenue Service building. But a dense tangle of woods still clings to the western slopes of the Liberty Memorial, and it’s not hard to imagine one chill night here in the pit of hard times.

The Union Station red cap told police he remembered a wheelchair. He had pushed it from the entrance to the women’s waiting room.

In the chair there was a young woman with her right leg in a plaster cast. On her lap lay a tiny baby in a gray blanket. The baby’s left wrist bore a hospital nametag. A middle-age man was with them. It was a Friday afternoon, May 16, 1930.

The red cap said the man asked him to look in on the woman from time to time and then wheel her to a Missouri Pacific train scheduled to depart hours later.

Some time passed. The red cap returned to the waiting room. The young woman was there, but there was no man or baby. She said she wasn’t feeling well, and that the man had taken the child to his sister’s house outside town. On the next check, the man had returned. He was alone and seemed nervous.

At midnight, said the red cap, the man and woman boarded a train.

The eastbound train steamed out of the sheds into darkness. At the same time, across Pershing Road from the station, up a gravel road and along a faint path in some woods below the Liberty Memorial, lay a rusting iron water tank. Inside the tank, wrapped in a gray blanket atop a bed of newspapers, lay a two-week-old, blue-eyed baby girl.

Liberty Memorial from the woods. Courtesy of the author.

Police found the couple at a house in Jefferson City. She was hiding in a dirt-floor garage out back, lying on a pile of rotting gunnysacks, in pain and barely conscious.

Some of their answers aligned. He was a house painter, and she was an unemployed waitress and factory worker. She had broken her leg. He was her father; she lived with him and her mother. There was a baby, born in a Kansas City hospital. There was talk of adoption, but the baby had disappeared at Union Station.

Beyond that, the stories diverged and details varied. She was married—or not. The baby’s father was an Indian from Oklahoma who had worked on the Bagnell Dam project at the Lake of the Ozarks; or the son of a Jefferson City minister; or a married grocery clerk from St. Louis.

She also had a son, four years old, dark-skinned and whose father was the Oklahoma man. Or the unknown father was the reason she never named the boy, simply calling him “Sonny.” The broken leg was from a fall down stairs at home, or she was pushed.

They were poor and couldn’t afford a baby. Or they had money, which they recently inherited. They went to Kansas City to keep his parents from knowing about the baby. The plan was to have the baby’s father take the child from Union Station and do with it as he pleased—or there was no such plan. The grandfather returned to the waiting room and found the baby gone. The mother, on painkillers, fell asleep in the waiting room. She woke and found the baby gone.

Ultimately the grandfather confessed. He led police across Pershing Road, up the gravel road, along the barely seen path within the tangle of woods below the Liberty Memorial to the empty, rusting iron tank. They couldn’t afford a baby, he said. And who would adopt a child with no father or no name?

The mother had agreed to let him leave the child in a random parked car. But the grandfather panicked, thinking someone might see him. He carried the child into the woods and discovered the old tank. A little shelter, he thought.

But when the late-night train left town, temperatures were dropping into the forties. A cold rain fell that weekend on the leaky iron tank in the woods.

A doctor at General Hospital said it would have been impossible for a newborn to survive such conditions for long.

It had been two nights and two mornings. From their nearby home, a man and his twelve-year-old son climbed the overgrown slopes toward Liberty Memorial, gathering firewood. A sound made the boy stop. It sounded like a sort of high-pitched chirping.

“Just a catbird, son,” said his father.

They carried their wood home, but the boy returned. He heard the same sound, a little fainter now. In the underbrush, he saw a rusting tank. Inside, there was a tiny baby. He ran home and fetched his mother.

The gray blanket and thin gown were wet from rain. The skin was cold and the little voice was weak, but the child was alive. Her left wrist bore a hospital nametag.

At General Hospital, where her adventure began, the blue-eyed baby girl was revived to ruddy health. People called the switchboard, wanting to adopt her. Well-dressed women came, asking to see her. A man visited, leaving ten dollars. The Journal-Post received a letter in crude handwriting:

“I want a baby sister. I want one with blue eyes and black hair. Please do it.”

The grandfather got five years for child abandonment, reduced from assault with intent to kill. Charges against the mother were dropped. The prosecutor decided her father had forced her cooperation. Mother and daughter spent two more weeks in the hospital, allowing the broken leg to mend.

For more than eighty years, General Hospital sent patients home through a stone portal etched with a quotation from Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice:

The quality of mercy is not strained.

It droppeth as the gentle rain from Heaven

Upon the place beneath. It is twice blessed.

It blesses him that gives and him that takes.

She’d gotten back her factory job, she said. She wanted to go home and take care of her children.

Seventeenth Street descends westward from Summit four blocks before dead-ending at a bluff overlooking the West Bottoms. There, four streets converge: Holly, West Pennway, Beardsley and Seventeenth.

Years ago, before the downtown freeway loop erased it, a fifth—Kersey Coates Drive—also connected here and ran more than a mile north along the bluff through West Terrace Park. The scenic drive and park had replaced several turn-of-the century wooden shacks perched on the hillside.

In the last hours of the winter of 1931, a Phillips 66 filling station sat on the bluff here at the end of Seventeenth, and just north of it an opening in the curb revealed a rocky pathway that led sixty feet down the steep bluff to a cottage. A throwback to those early wooden shacks, this was the home of the A.E. Mann family.

Remains of Kersey Coates Drive. Courtesy of the author.

Probably better than anyone, forty-nine-year-old Arthur Mann, an Arkansas native who worked as a lubricator at an oil company off Southwest Boulevard, knew the pros and cons of this neighborhood aerie.

Writers and artists had compared the terraced park and Kersey Coates Drive to something in the Italian countryside. One visiting author considered the views one of the best among the world’s cities. “A long sweep of the Missouri, winding its course between the sandy shores which it so loves to inundate,” he wrote. “Beyond, the whole world seems to be spread out— farms and woodland, reaching off into infinity.” Then he described the foreground scene: “warehouses and packing houses, and the appalling web of railroad tracks, crammed with freight cars, which form the Kansas City industrial district.”

At times, this was a place for criminal activity. Two years earlier, a cashier had been robbed of payroll money on Kersey Coates Drive. The next year, a local bootlegger was shot dead in his car on the same road.

And there had been near-disasters with vehicles. The man running the filling station had seen more than one driver misread the curb opening above the Mann cottage as a continuation of the street, stopping with front wheels hanging over the precipice.

So possibly Arthur Mann and family—forty-nine-year-old wife, eleven-year-old daughter, seventy-year-old mother-in-law—were not unprepared for the early morning of March 21, 1931.

It had been raining in Kansas City, and temperatures after midnight hovered just above freezing. At 1:15 a.m., the Manns were shaken from sleep by a loud crash.

Outside, Arthur Mann found a 1930 Ford coupe leaning on two wheels against the splintered remains of his porch. Two young men lay bleeding on the rocky ground nearby. A third was up, trying to move one of the others. Seeing Mann, he asked to go inside and wash his hands.

“Please don’t call the police,” he said. “Don’t tell our folks; they’ll be scared to death. Just call an ambulance, quick.”

Police learned the three were students at the University of Kansas, all from small Kansas towns. Out for a drive, they’d stopped for barbecue and were on their way back to Lawrence. Instead of turning into Beardsley from Seventeenth Street and traveling north to the Intercity viaduct, they drove straight ahead at thirty-five miles an hour, through the opening in the curb, bouncing then rolling over and over, down the cliff into the Mann house.

Two hours later at General Hospital, one of the three—an honor-roll student and fraternity president—died of his injuries.

Back at the Mann house, police searched the car and grounds for evidence of alcohol, finding only a blanket, a small radio, some tools, a deck of cards and a raincoat. And up on the roof of the house, a man’s hat. The label was from a Lawrence store. The headband was bloodstained.

Today, the cliff is a jungle of weeds and trees. The Phillips station and the Mann house are long gone, replaced by a tattered billboard and a sign warning trespassers. Nearby, the only surviving witnesses to a fatal morning in 1931—a stone wall, rusting handrail and grassy roadbed, all remnants of Kersey Coates Drive—still gaze toward the river and the world spread out, reaching off into infinity.

The rains come and the Missouri River rises, tickling the trunks of slender green trees along the shorelines between the downtown bridges. Its current runs strong and silent, and the slate-colored waters are often full of logs and branches and the flimsy, man-made debris that any good spring storm will launch on a bon voyage toward the Gulf of Mexico.

The pedestrian walkway known as the Town of Kansas Bridge, above the remnants of the old Municipal Wharf at the foot of Main Street, is a good place to watch.

It looks almost as if the river has remembered something of its wild youth, when it did as it pleased. Serpentine and studded with sand bars, it was slow and small in wintertime. Come spring, it would gorge on rains and spread itself over the land and then recede, sometimes into new channels, reinventing itself.

Eventually, progress demanded that wildness be tamed.

I’m down by the river, listening to a soundtrack provided by young frogs, angry blue jays and a freight train on the ASB Bridge, and I’m contemplating a partial list of those who have passed this way before me: Indians of various tribes, African slaves and Frenchmen in wooden canoes; a dead man, ten days afloat from St. Joseph; kayakers, steamboat captains and ferry operators; Creoles onshore, hauling keelboats with long ropes; gold rushers, bargemen and thugs disposing of unwanted weapons; eight Boy Scouts bound for St. Louis in yellow Navy surplus rafts; gypsies on shanty houseboats, catfish noodlers and Lewis and Clark; and army engineers.

Remnants of the working waterfront on the Missouri River. Courtesy of the author.

I’m wondering if there might be two types of people historically associated with this river—those who fight the current and those who don’t. The former group would be ably represented by the army engineers.

The riverfront is slowly returning to a green, seminatural state of grasses, brush and cottonwoods, and people are enjoying amenities like the pedestrian bridge, a park and a landscaped shoreline trail. It’s a far cry from the industrial scene of years ago. But despite its historical importance, the Missouri sometimes seems like an afterthought in Kansas City.

There was a time when it could draw a crowd. As in 1932, to celebrate the opening of a new six-foot navigation channel from Kansas City to the Mississippi River; it was a channel that ensured yearlong passage with no snags or sandbars to prevent a barge from carrying the fruits of heartland labor to the world. It was a celebration of engineering, the use of steel, stone and woven willow branches to force the river to scour its own new channel.

And fourteen years later, when people turned out for a ceremonial groundbreaking for a new flood wall from the Kansas line to the ASB Bridge. It was the tiny beginning of the massive, $1.2 billion federal Pick-Sloan project, which extended the navigation channel to Iowa, but it also provided flood control, electricity production, irrigation and recreation opportunities via a series of upstream dams and reservoirs.

“It will stop the ravages of floodwaters and provide billions of gallons of water for irrigation and untold amounts of cheap electric power for industry,” proclaimed General Lewis A. Pick of the army engineers, spading a chunk of West Bottoms clay at the foot of Mulberry Street. “Think what it will mean to the businessmen of the Middle West.”

The general answered himself by proclaiming “a new and greater era, an era of security, progress and better living in the valley of the Missouri.”

It’s possible to sit on the banks of the Missouri and not think about some unintended consequences of the general’s new and greater era, such as the anger of Native Americans, upset over tribal acreage lost to the chain of reservoirs; the upriver–downriver dispute over water for recreation interests versus shipping interests; or the concerns of environmentalists about loss of habitat and wildlife dependent on the river’s natural flood cycles. It’s possible—especially in a Kansas City spring, when the river looks youthful and spirited.

So now I’m sitting here on some old concrete steps that lead down to the water’s edge, daydreaming about going with the flow, living as a gypsy on my shanty houseboat, watching fields and towns slide past and drifting with the brown current toward the sea.

The fried-egg sandwich in the diner off the Union Station lobby was food for thought. One morning before the place went out of business, I was sitting at the counter, enjoying that breakfast and thinking about a story my grandmother often told.

It was a story from the early 1930s about some neighbors she once had. My mother’s family then lived in an Armour Hills bungalow on Edgevale Road. These neighbors—a man, woman and a young girl—had recently moved into a rented house across the street.

The east entrance at Union Station. Courtesy of the author.

The house attracted mysterious activity: cars with out-of-state tags and people coming and going at all hours, often carrying odd luggage. The renters kept to themselves, and no one was sure about their line of work. My grandmother would not let my mother and aunt play with the little girl, so the three children would stand in their respective yards, staring at each other across the street.

The upshot of her story was that one morning, some men walked out of the house with their odd luggage, got in a car and presumably went to work. But they didn’t come home that night or ever again.

I was thinking that events elsewhere that morning must have inspired other stories, told and retold countless times.

It was the morning of June 17, 1933—a Saturday.

My own story, had I been in Union Station that morning, might begin early at the Harvey House counter with a plate of eggs and a newspaper, reading about a couple of outlaws. Pretty Boy Floyd and Adam Richetti were running from the law somewhere just south of Kansas City after having kidnapped a rural sheriff. The U.S. attorney general was planning a war on crime. “It is warfare, pure and simple,” he was quoted as saying. “Gangsters must go.” And federal officers had captured an escaped convict named Frank Nash in Arkansas. They were returning him to Leavenworth on a train. The weather was going to be hot, near ninety. But it was still comfortable, maybe seventy, just after 7:00 a.m.

He was a retired country editor. His story would begin when he arrived on the 7:15 from Moberly. He climbed the stairs from the train shed to the lobby and headed toward the taxi stand outside the station’s east entrance. What if he hadn’t stopped first to buy that cigar at the cigar stand?

He was a clerk in the station bookstore. He noticed a group of several men walking in close formation across the marble floor of the lobby, toward the east entrance. One of the men was wearing handcuffs. Other people in the lobby were following the men out the door. He followed, too.

He was an attendant at the taxi baggage stand. He saw three men in the group carrying rifles or shotguns. He remarked about how well the prisoner was guarded.

He was the taxi starter, hailing cabs from the wide front sidewalk. He saw the group pass him and cross the lot to a parked car. He saw the prisoner get in the car first.

He was a station red cap. He had just helped put a passenger into a waiting cab. He turned around and saw a man with a short gun.

He was a truck driver from St. Louis, unloading tires down the street at the Goodrich Company. He heard what sounded like a firecracker. “Starting their Fourth of July celebrations early,” he said to a co-worker.

He was a cab driver, waiting in line outside the station for a fare. He heard one shot, turned and saw a man firing a machine gun at a parked car, swinging it from one side to the other.

She was a mother meeting her son’s train, standing near the lobby doors to the train sheds. She heard shooting, saw flashes of red near the entrance and people running toward her.

She was the Harvey House cashier. She heard glass shattering at the front of the station, saw shards spray across the lobby and people running. Must be a holdup, she thought. She grabbed money from the register, stashed it under the counter and phoned in a riot call.

She worked the Travelers Aid desk in the lobby. She saw six Catholic nuns among dozens of pedestrians on the sidewalk. She ran out and called to them. Four ran; two stood frozen. Someone grabbed their arms and pulled them inside.

He was a cab driver. He saw four gunmen escape in a dark, late-model Chevrolet sedan, heading west on Pershing at high speed.

He was a streetcar operator. At 7:23 a.m., while unloading passengers at Thirty-first and Main, he saw a dark sedan, maybe a Chevrolet, make a wide, screeching turn from Thirty-first into Main and then race south.

He was a railroad man, up from the sheds, having heard shooting. Looking outside, he saw someone pointing at a car and ran to take a look. There were three bleeding men on the ground and three more in the car; one of them was handcuffed. A shell casing lay on the ground. He picked it up and put it in his pocket.

She and her mother had driven down early that morning to meet a train and parked in the first row. She wanted to wait in the car. Her mother said no; she needed her because there were two arrival doors to watch. When they returned, they found a crowd near their car, bodies and blood on the ground and in the car parked beside theirs. Their car was laced with bullet holes.

Whenever I heard my grandmother’s story, I had two reactions. One, that it was cautionary: If you’re engaged in mysterious all-hours activities involving odd luggage, one day you might not come home from work. And two, that she had a good imagination.

But it turns out she was partly right. Although controversy exists about the identity of some of the gunmen—Was it Floyd and Richetti? Local thugs?— when prisoner Frank Nash and four law enforcement officers died in the Union Station Massacre, one name is certain: Verne Miller.

After the killings, police learned that Miller, along with his girlfriend and her daughter, had lived under an assumed name in the rented bungalow across Edgevale Road from my grandparents. And there was evidence that other notorious figures of the day had spent time there.

But my grandmother was wrong about one thing. Miller and his cohorts apparently did return home for at least one more night in the rented bungalow, even as she sat across the street in her living room reading a story in an evening newspaper about their day at work.

It was a customer’s receipt from Woolf Brothers clothing store, issued to a doctor who lived on Wyoming Street, for the amount of seven dollars. Dated January 10, 1934, it got me wondering what else happened in town that day.

A man died at home on Sixty-eighth Street; a woman died at home on Jefferson Street; a man died outside a filling station with a burglar’s jimmy and a spark plug in his pocket and two police bullets in his head. A woman put on a blue dress and shot herself twice with her husband’s .35-caliber pistol, killing their unborn son.

The Woolf Brothers receipt. Courtesy of the author..

It was a Wednesday, cloudy and cold in Kansas City, and there was snow on the ground. Someone bought peppermint candy ice cream, which was the special at the Linwood Ice Cream Company. Someone ordered a ton of semianthracite, the special at Neil Barron Coal. Someone bought a tin of Shinola at Katz Drug. Someone ordered two loaves of salt-rising bread from Wolferman’s grocery. Someone dreamed of wintering in Havana.

Twenty-five hundred people received licenses to drive. Ten couples got licenses to marry. One woman sued for divorce after forty-six years, while another couple celebrated sixty years together. Someone bought tickets to a polio benefit at the Pla-Mor Ballroom, celebrating President Roosevelt’s fifty-second birthday. Someone boarded an airplane at Municipal Airport, leaving for New York. Someone booked a sleeper on a westbound train.

She paid thirty-five cents for lunch and a tea-leaf reading at the Egyptian Tea Room. He hoped someone would find his dog, a wire-haired terrier named Punch—white with a brown face. She answered an ad in the newspaper: “Girl—white, 20 to 30 years old; housework and cooking, care of 2 children; stay nights; city references; $5 a week.”

He received his badge at a meeting of Boy Scout Troop 24. They robbed a bank of $2,500 and escaped in a 1933 Dodge sedan with Kansas tags, 19-6110. They played cards and danced with their wives at a party thrown by Meat Cutters Association Local 576. He sank the last-minute winning basket in the church league at Van Brunt Presbyterian.

Someone paid a quarter to see Duck Soup and a Betty Boop cartoon at the Plaza Theater. Someone paid a quarter to hear the George E. Lee and Bennie Moten Combination Orchestra at the Harlem Nite Club. Someone paid fifty cents to take Brazilian Carioca lessons from Professor Wolfe. Someone stayed home to listen to Amos ’n’ Andy on the radio. Someone lingered over a four-letter word for “alcohol radical” in a crossword puzzle.

A doctor spent seven dollars at a clothing store near his downtown office. He was a thirty-nine-year-old chest physician with a wife and no children. The day was no. 14,327 in his earthly allotment of days.

If on his final day—no. 31,783—the doctor could have been shown the receipt, perhaps he might have recalled something specific: a favorite tie, shirt or pair of shoes; a night out with his wife; a visit from a patient; maybe his single best day, or his worst. He might have stared at the date and wondered where all the days had gone.

Like me, the guy was out enjoying the warm February weather. We were on a block of Campbell Street that is lined with well-worn but still-handsome houses of a familiar type in Kansas City: multiple stories, front porches and postage-stamp yards. It was an historic neighborhood, the street signs say, and it’s not hard to imagine grander days when nearby Armour Boulevard was a more fashionable address.

We stopped to chat. It was a good old neighborhood, we agreed. He just moved in recently, he said, and lived in that house there; he was fixing it up. I was just out for a stroll, I said, killing time before a haircut appointment. That was partly true. I didn’t say I was here because of what I knew about his property; that a lifetime ago—Valentine’s Day 1934—two lovers died, violently and mysteriously, on his patch of sidewalk.

As do all mysterious crimes, this one had a set of givens.

There were two bodies—a man and a woman—sprawled across the sidewalk. They were discovered at 11:15 p.m. by two neighborhood teenagers who heard two gunshots. The woman had been shot once in the right temple, and the man was shot once in the mouth. The man had ninety-five cents in his pocket and a .38-caliber revolver in his right hand.

Beyond that, police learned she was a nineteen-year-old stenographer for a Kansas City mail-order company. He was a twenty-three-year-old student at William Jewell College in Liberty. They had been on a date to the movies. He had picked her up at her home, a door away from the crime scene, at about 8:00 p.m. that evening. She had been renting a room there for about three weeks. They had left the house in good spirits. They were planning to marry after his graduation in June. He had a job prospect in Chicago.

The lovers and their Campbell Street sidewalk. Courtesy of the author.

In time came a secondary layer of information. He grew up in a small southwest Missouri town as the tenth of eleven children. Friends said he was always short of money, but they knew him as carefree and pleasant. Others called him “excitable.” He held a job cleaning a campus building, and he liked to whistle as he worked. Friends called him the “whistling janitor.” He was a divinity student.

She and four sisters grew up in an orphanage in Liberty. She graduated second in her high school class. She sometimes suffered brief spells or attacks when she became confused and irrational for several minutes; she then recovered with no apparent effects. She was under treatment. Friends said she always appeared happy and often sang or hummed while she worked.

And, finally, there was a third layer. It was a letter from him that was discovered in her room:

“Darling, you are sure of me, aren’t you? You know I love you more than life itself. If I weren’t sure of you I’d be miserable most of the time. When we get out of this mess, we’re going to keep our noses clean. Life is too short. We don’t want anything to come between us. I’ll do my part and am sure you will do yours.”

The landlady remembered her saying she would not marry him, that “it would be silly for us to marry when he has no job nor any prospects of one.” A friend remembered him saying it “was a lovely thing for lovers to die together.” The autopsies revealed no disease or pregnancy. Police called it a murder–suicide, with no clear motive.

So we’re left to speculate and to connect whatever dots we can find. Did she intend to marry him? Was there really a job prospect? What was the nature of the “mess?” Did she suffer one of her spells during their date? Did he talk of the beauty of dying together? And what movie did they see? Was it the comedy, musical, western, hospital drama or jungle thriller playing in one of many neighborhood theaters? Did he take her downtown, treating his valentine to something more pointed and grand? Perhaps it was the hard-times, love-and-loss story at the Mainstreet. Or the storybook love-and-loss story at the Midland.

It’s the music—his whistling and her humming—that lingers in my mind.

In the movie I would make, the final scene is serene and almost beatific. On the drive home, he’s been whistling a haunting tune he can’t get out of his head. She says something like, “Oh, I love that song. What’s it called?” and begins to hum softly along. He pulls the car to the curb, gets out and opens her door. They walk toward her house. The day has been unseasonably warm and the night cool but not uncomfortable. He slips an arm around her shoulder, his hand into his coat pocket and feels the smooth weight of the gun. “Wait a minute,” he says to her. “Close your eyes.” And the tune loops again and again.

Standing on this corner, where the new downtown meets the old, I’m trying to picture an earlier 1300 block of Main, before its Power & Light District makeover.

Except for a brave tuxedo-rental store, it wasn’t much. There was a cocktail lounge, a place that sold newspapers and porn magazines, a haunted house, a massage parlor and several asphalt car pastures. One of those parking lots was right here in the shadows of the Mainstreet Theater and the Hotel President. It’s now a new storefront that stands vacant in these hard times.

Now imagine a different storefront during even harder times; and two policemen with riot guns, answering a burglar alarm on a cold Friday morning the week before Thanksgiving 1935.

Each man received a coat that fit and was out the door. Courtesy of http://criticalpast.com.

It was the morning after opening night of the Kansas City Philharmonic’s third season, its last at the old Convention Hall at Thirteenth and Central.

The concert ended at 10:00 p.m., and the city’s black-tie finest—in top hats, furs and imported topcoats—milled about in the chilly night air, admiring the lights on the new Municipal Auditorium that was nearing completion across the street. The arena’s three marquees were switched on just for the concertgoers.

No doubt the brilliant lights and the music of Sibelius, Strauss and Brahms helped soothe any disdain for President Roosevelt’s extravagant spending: $4 billion to put millions of unemployed to work. Some of that money was in this new arena.

As the crowd drifted home, a lone figure just beyond the glow of lights made his way toward the corner of Fourteenth and Main, then another and then a third. Thinly dressed, they huddled outside a locked storefront. At 11:00 p.m., the temperature was thirty-four degrees.

At 3:00 a.m. it was thirty-two degrees. Fifty men waited outside the store. By 8:00 a.m., the line stretched up Main to Thirteenth, west a block to Baltimore and back south toward the Hotel President. It was twenty-six degrees. Those in line wore light jackets or overalls and several shirts. They were old men and young boys. Some carried a classified ad torn from a newspaper: “OVERCOATS—700 free to men unemployed. Apply 8 a.m. Friday. Gateway Loan and Sporting Goods. 1330 Main.”

What had started years earlier as a way for proprietor Louis Cumonow to get rid of fifty extra second-hand coats had become an annual event. He bought coats from a man in Philadelphia, who got them from military recruits who had no further use for them. Then he published an ad, and he gave them away—first come, first served.

That morning, because of the cold, he and his clerks fitted the hundreds of men inside the store, four at a time, and quickly, under a minute each. Each man received a coat that fit and was out the door, and another came right behind him. Then the cops arrived with their riot guns and demanded to know what was going on.

No burglary, said Louis Cumonow. He was just giving away coats. Someone must have dropped one on the alarm button.

The seven hundred coats were gone by 10:00 a.m. But customers remained, and Louis Cumonow kept giving away coats, no questions asked.

“I picked out about thirty old men, cripples and little boys and gave them coats out of my regular stock,” he said later.

“Of course some don’t deserve them. But most do. Today three men came back with their new coats and wanted to do some work. That pleases me enough.”

Elsewhere in town that day, men were buying overcoats at Jack Henry, Rothschild’s and Woolf Brothers. “Imported from England—Soft, luxurious, wrinkle proof—Alpaca and Angora yarns—Generous lines that are slightly fitted, giving that smart English Drape—$28.50 to $65.”

And the next morning, Louis Cumonow ran a new classified ad: “TOPCOATS, overcoats, jackets; left in pawn; $3 up. Gateway Loan, 1330 Main.”

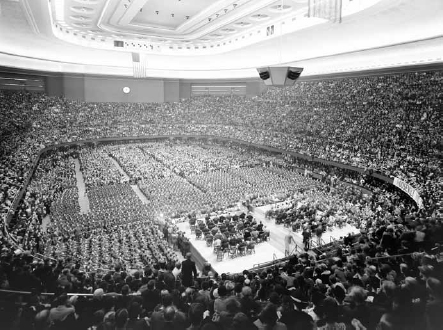

I’m standing in the southwest corner of the upper tier of the new Municipal Auditorium. With me are twenty thousand other folks, outnumbering the seats, with many standing in the aisles. We’re watching and listening to the president of the United States, Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

“America has lost a good many things during the depression,” President Franklin Delano Roosevelt said during a visit to Kansas City on October 13, 1936. Courtesy of Missouri Valley Special Collections, Kansas City Public Library, Kansas City, Missouri.

FDR is standing behind a rostrum built especially for this day: aluminum with reading lights, electrical hookups for the house speakers and the radio broadcasts, handrails and side panels that conceal his legs, which have been withered by polio.

Officially, this is the auditorium’s dedication, though it’s been open since last December. But it’s an election year, and we’re a stop on the president’s ten-day, twelve-state campaign tour by train. He’s just arrived from Wichita, in the home state of his opponent, Alf Landon, where he cited a “gospel of fear” spread by Republicans about his administration.

Here, a large contingent of ROTC boys is sitting down front, as are members of the Young Democratic Clubs of several states; the president has mentioned the Civilian Conservation Corps, a work program for youth his administration founded. He said:

America has lost a good many things during the depression. We have lost, for example, that false sense of values that puts financial success above every other kind of achievement. We have lost something of that feeling that ours is an “every-man-for-himself” kind of society, in which the law of the jungle is law enough…But many things we have saved—things worth saving. We have saved our morale. We have preserved our belief in American institutions. We have saved above all our faith in the future—a faith under which America has only begun to march.

Afterward, the ovation will be loud and long, and FDR will walk with assistance from the stage down a wooden ramp to a waiting open car. He’ll leave the auditorium for the warm Tuesday afternoon sunlight by way of downtown streets lined with thousands more people waving flags and handkerchiefs and holding balloons all the way to Union Station.

Later today, in Detroit, Governor Landon will warn his audience that Roosevelt is building a strong central government and possibly a dictatorship. Just before the election, Literary Digest will publish its poll assuring a Landon landslide. And then, in November, the president will win sixty percent of the popular vote, carrying forty-six of forty-eight states, including Kansas.

Tonight in Kansas City, after the president’s special train eases out of town toward St. Louis, after the streets are cleared of snarled traffic, a taxi driver will pull over at Twelfth and Baltimore.

“I don’t know what the New Deal has done for business,” he’ll say. “But all Roosevelt has to do to get me out of a depression is to come to town.”

Gazing down the long sweep of Gillham Park—the grassy finger of lowland playground tucked between the Hyde Park and Rockhill neighborhoods alongside Gillham Road, south of Thirty-ninth—I’m not seeing an ideal spot for a city-sanctioned, toxic bonfire.

I don’t know whether such an event is something George Kessler imagined when he designed the parks-and-boulevard system a century ago. I’m pretty sure of what the neighbors would say now.

But late one January in the hard times of 1937, it seemed a perfectly logical idea. It was just one of several heard around town that week.

It was Sunday of the week after President Roosevelt’s second inauguration. News was dominated by the flooding Ohio River and a sit-down strike at General Motors. Sunday was opening day of the Used Car Show, during which Kansas City auto dealers would be trying to clear lots to make way for the new models. That evening, just up the hill from Gillham Park in a house on Holmes Street, a visitor was speaking to a small group of friends. A Jewish man, editor of the Palestine Daily Mail in Jerusalem, said “the Jews have re-inherited Palestine; we have not conquered it,” attributing recent trouble there to German-made weaponry provided to Arabs by the Nazis.

Detail of the parks department’s maintenance building at Gillham Park. Courtesy of the author.

“A permanent solution of the recurrent Jewish–Arab riotings will be reached within about five years,” he said. “By that time the two groups will have reached an approximate parity in population.”

Two days later, the Advertising Club welcomed French visitors to a luncheon at the Hotel Baltimore downtown; they were promoters of a Paris exposition to open in May. One, an economic writer for Le Petit Parisien, dismissed concerns about events in Europe. Rearmament, he said, presaged peace, not war.

“As a Frenchman,” he said, “I believe that as long as France and England stand together there will be no European war.”

The next day, four thousand people filed into Municipal Auditorium for a program sponsored by a group called the World Peace Council of Kansas City. Two years earlier, Congress had passed the Neutrality Act, which prohibited the sale of arms to any country at war with another. In a Gallup Poll, seventy-five percent of Americans had said any declaration of war should be subject to a vote of the people.

Speakers that day included two Englishmen—a young college student and an old preacher.

“We must be firm and resolute and not be deceived by idealistic war slogans,” said the student. “We realize the tremendous ‘ideals’ people die for are mostly tremendous farces.”

“If you can keep peace in your hemisphere it will light a ray of hope in the Old World,” said the preacher. “Don’t waste your genius and resources to devise ways to destroy, but use them to drive fear and poverty from the world.”

While the auditorium crowd listened to pleas for peace, workmen with tow trucks were piling junked cars just south of the old maintenance building in Gillham Park, About a hundred such heaps, deemed unsafe for city streets, had been donated by dealers all over town for a publicity stunt to promote the Used Car Show and to help sell old Fords, Chevrolets, Studebakers, Hudsons, Packards and Terraplanes.

Temperatures had been in the forties all day, but patches of snow clung to hillsides flanking the park. Spectators—perhaps thousands—formed a ring from Locust to Kenwood and Thirty-ninth to Forty-third Streets, watching a tanker truck spritz four hundred gallons of gasoline and kerosene on the stack of cars. Firefighters, police and a hundred Boy Scouts stood by.

At 8:00 p.m., some men representing the fire department, the Safety Council and the car dealers lowered torches to four fifty-foot “fuses” of gasoline-soaked straw.

The next morning, a Times reporter described “a dozen pillars of fire” shooting thirty feet skyward, and the “brightly lighted” surrounding hillsides. Spectators cheering as tires “burst loudly, some burst shrilly and one exploded with a bang.” The burning carcasses were “red in the heavy smoke and flames.” A southern breeze “carried the fumes of burning rubber into the crowd north of the pyre, and hundreds of watchers fled.”

“FIRE MAKES ROADS SAFER,” the headline declared. The bonfire was reported to be part of a “campaign to remove dangerous antiquated machines from the streets.” The article closed with promoters announcing intentions to “make this an annual affair. It’s a lot of fun and it serves a good purpose.”

Here in the twenty-first century, I see that this idea—and its “good purpose”— existed only in the Kansas City Star and its partner, the Times, where Used Car Show advertising appeared, and not in the competing Journal-Post.

I’m thinking the value of any idea depends on where you’re standing and which way the wind is blowing.

I’m standing at a window on the original mezzanine of the Hotel Muehlebach, looking at the old hotel’s wavy reflection in the modern glass tower across Baltimore Street. A dreamlike image, it creates the appropriate state of mind for imagining a legendary Hollywood director at work here.

Cecil B. DeMille stepped off the train from Chicago at 11 o’clock the morning of January 21, 1938. He had written a tight script for a single day here: lunching with local dignitaries, including the mayor, in the Muehlebach’s Tea Room; speaking at a preview of his latest movie, The Buccaneer, at the Newman Theater; and giving his daughter in marriage in the Muehlebach’s penthouse. Kansas City, centrally located, provided the ideal set for killing several birds with a single stone.

The storyline had DeMille meeting his wife, daughter Cecilia, and her intended, Joseph Harper, all who had arrived earlier by train from Los Angeles. With him from Chicago he had brought two actors from The Buccaneer, Margot Grahame and Akim Tamiroff, who would appear at the preview and then play supporting roles as bridesmaid and best man.

But as the DeMille entourage hurried across the lobby of Union Station, a young girl from Texas approached and reached for the director’s hand. She was Minnie Jean Lamb, age twelve, and she recited a line she must have rehearsed many times over the five hundred miles from Texarkana.

“I want to go to Hollywood,” she said.

The Hotel Muehlebach, reflected across Baltimore Street. Courtesy of the author.

Later at the hotel, the DeMille family sat on a sofa and chatted with reporters.

“The wedding tonight will be simple,” said the director. “Yes, 11 o’clock. That is, if I get back here from the theater by that time.” Photographers asked for a few pictures.

“Here, now, we shouldn’t sit that way,” DeMille said. “I should be over here and Cecilia next and you move over there by Joe. Now get your mind off that camera. How’s that light coming from the left window?”

That night, a full house at the Newman applauded as the house lights came up and the director strode across the stage and spoke briefly about the heroism of Jean Lafitte, the pirate protagonist of The Buccaneer, and then introduced the two actors, who gave brief thanks and accepted flowers. Then they went back to the Muehlebach.

It was well past 11:00 p.m. before the photographers had finished with the wedding party and the ceremony could begin. The director marched confidently past the snapdragons, roses and fifteen guests to deliver the bride to her groom. The couple recited the vows, each for a second time in their lives. As DeMille had announced to the Newman audience as he was leaving for the hotel, this was his “greatest production.”

Across town in the darkness of her aunt’s bungalow on Jefferson Street, a twelve-year-old girl from Texas must have been replaying her scene, now on the cutting room floor.

“I want to go to Hollywood,” she had said.

“So does almost everyone else in the country. You’re a little young for my pictures.”

“But look at Shirley Temple. She’s young and she’s working.” “Yes, but she’s not working for me. You go back to school.” And so ended the dialogue, allowing Minnie Jean Lamb to return to Texarkana and tell a story of how Cecil B. DeMille directed her life story.

Hallowed ground in Kansas City sports history is not named Kauffman or Arrowhead, but Monarch Manor—a development of new Craftsman-style houses where the curve of East Twenty-first Terrace mimics the sweep of a grandstand and the sidewalk echoes a right-field foul line.

The curve of the street mimics the sweep of a grandstand. Courtesy of the author.

As true Kansas City sports fans know, there used to be a ballpark here. It had a succession of names—Muehlebach Field, Ruppert Stadium, Blues Stadium and Municipal Stadium—and it was home turf for more than fifty seasons of Blues, Monarchs, Athletics, Royals and Chiefs.

By my estimates, first base was right about here, between Garfield and Euclid Streets, several feet under the infill soil of what is now Lot 35, Monarch Manor. John “Buck” O’Neil worked this ground for the first time as a Monarch in the second game of the 1938 season-opening double-header, but I’m thinking of another obscure milestone that came a year later: Lou Gehrig’s final game.

It was baseball’s centennial season, and it was the first time the New York Yankees had played in Kansas City.

The Yanks arrived early Monday morning, June 12, 1939, rolling into Union Station aboard three Pullman sleepers. They had just come from beating up the lowly St. Louis Browns to play an exhibition against the Blues, their American Association minor-league affiliate.

New York had won the 1938 World Series and had a current record of thirty-seven wins and nine losses. The Blues were Little World Series champs and would win 107 games in 1939. (Years later, they would be named one of the all-time great minor-league teams.)

The Blues were led by a young infield of future major leaguers: Johnny Sturm at first, Jerry Priddy at second, Phil Rizzuto at short and Billy Hitchcock at third. Their slugging center fielder, Vince DiMaggio, would be playing against his little brother, Joe, who was the Yankees’s slugging center fielder.

Gehrig, who was about to turn thirty-six, would be in uniform but not expected to play. Six weeks earlier, the longtime Yankee captain had taken himself out of a game in Detroit, ending a streak of consecutive games played after fourteen years and 2,130 games.

“There’s something wrong with me,” he had told a friend. “It started over the winter. I lost weight and I felt like I was getting weak. This spring it just seems like I’m weaker and weaker and weaker…I don’t know what it is.”

Today, most fans believe the Detroit game was his last. But there was one more.

Although the Yankees would be in town just for the day, they checked into the Hotel President to shower, eat and rest before heading to the ballpark for 1:00 p.m. batting practice.

Besides Gehrig and DiMaggio, these were the Yankees of Crosetti, Gordon, Henrich, Dickey, Keller and Gomez. They were heroes, previously seen by Kansas City fans only in newspaper photos or grainy newsreels at the movies. People filled streets in front of the President and clogged traffic.

All twelve thousand box and reserved seats at Ruppert Stadium had been sold out for days. Gates opened at 11:00 a.m.—an hour ahead of schedule— for walk-ups to buy five thousand general admission seats. By a little past noon, only standing-room tickets remained.

They overflowed the seats and spilled onto grassy slopes behind third base and right field. They stood on ramps or six deep behind the last row of the grandstand. They climbed the pitched roofs of concession stands. They perched atop the outfield wall. All 23,864 of them. The temperature was in the seventies, and it was muggy when the first pitch was thrown at 2:30.

“This is quite a crowd,” said a New York reporter in the press box. “We played to eight thousand in Sunday’s doubleheader in St. Louis.”

The Yankees scored a run in the first and then took the field. One of them walked slowly across the diamond and took his position at first base. It was not Babe Dahlgren, who had replaced Gehrig in the regular starting lineup, but Gehrig himself.

After the game, the Yankees returned to the hotel. They had a game Wednesday in New York, and they’d be riding their Pullmans behind an eastbound night train—all of them except one.

Lou Gehrig would be spending the night at the Hotel President. There was an early flight to Minnesota the next morning. He had an appointment for a checkup at the Mayo Clinic.

“I guess everybody wonders why I’m going, but I can’t help believing there’s something wrong with me,” he told a Kansas City reporter. “I’d like to play some more and I want somebody to tell me what’s wrong. Usually a fellow slows up gradually.”

Gehrig’s biographers have suggested he played that day because the huge crowd wanted to see him. Or perhaps he wanted to give it one more try before his Mayo examination.

The box score shows the Yankees beat the Blues 4–1, and Gehrig played three innings. He grounded to second in his only at-bat and recorded four putouts at first. The only suggestion of anything wrong was a reporter’s description of a Blues player pushing “a hit past the slow-moving Gehrig.”

Years later, others who played that day had darker memories. Blues catcher Clyde McCullough recalled a line drive that knocked Gehrig on his back. Two of Gehrig’s fielding chances were said to have been errors that weren’t scored as such. Phil Rizzuto, who had idolized Gehrig as a youth, remembered a once-powerful body that seemed shrunken and hobbled.

“Oh, it was a sad day,” Rizzuto said.

The Mayo Clinic diagnosis was amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

In two weeks, Gehrig was back in New York, giving his retirement speech in front of a clutch of microphones on the Yankee Stadium infield, calling himself “the luckiest man on the face of the earth.” In two years, he was dead.

Surely those final two years were overcrowded with bittersweet memories: teammates and opponents; home runs and strikeouts; pennants and disappointments; and the beginning, and the end, of the streak.

And maybe even that last sliver of time at first base, the smooth leather of an old mitt, the green Kansas City grass, the start of the windup, the white ball, waiting.