Vietnam Veterans Against the War carry out their “Dewey Canyon III” protest, styled, following Nixon administration rhetoric, as a “limited incursion” into the land of the Congress. Here protesters unfurl their banners on the western side of the Capitol building (Stanley Commisiak).

The VVAW vets had an authoritative voice because they were authentic, not the phonies the Nixon White House sought to paint them. The medals and ribbons worn by this former Marine sergeant from the 3rd Reconnaissance Battalion indicate he had won both the Silver and Bronze Stars for combat actions, had served twice in Vietnam, held two Purple Hearts, the Meritorious Unit Award, and the Combat Action Ribbon, among others (Bernard Edelman).

At the climax of Dewey Canyon III, the veterans hurled medals over a chicken-wire fence hastily erected by Capitol police to keep them from returning their medals to Congress. In one of the iconic photographs of the antiwar movement, former Marine helicopter crewman Rusty Staub throws a gallantry medal over the barrier (Bernard Edelman).

A terrain relief model of the French entrenched camp at Dien Bien Phu that was created by Vietnam People’s Army mapmakers. Today, the model is on display at the People’s Army Museum in Hanoi (author’s collection).

President Dwight D. Eisenhower greets Ngo Dinh Diem at National Airport on May 8, 1957—the third anniversary of the fall of Dien Bien Phu. This would be Diem’s only visit to the United States as South Vietnam’s leader. Behind Eisenhower, Secretary of State John Foster Dulles greets ambassador Elbridge Durbrow (National Archives).

Journalist David Halberstam coined the phrase “the best and the brightest” to denote the standing of the officials who helped presidents make their Vietnam decisions. Here President Kennedy meets with some of his top officials in the Oval Office on January 3, 1962. From the left, Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson, Kennedy, Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara, White House special military representative General Maxwell B. Taylor, and Deputy Secretary of Defense Roswell Gilpatric (Kennedy Library).

A few weeks after February 27, 1962, when Vietnamese air force pilots bombed the Presidential Palace in an attempt to kill him, President Diem staged an elaborate event in Saigon at which the Air Force command renewed its vow of support. The white-uniformed troops presenting arms behind Diem are members of his CIA-sponsored, Filipino-trained Presidential Guard (National Archives).

Madame Nhu, née Tran Le Xuan, the wife of Diem’s brother, who increasingly played the role of South Vietnam’s First Lady and a key powerbroker, created her own nucleus of support. An important element of that base were the women cadres of the Republican Youth. Founded by Madame Nhu, by late 1962 the group was strong enough to appear in Saigon’s national day parade. Lining the street are Presidential Guards and helmeted officers of the National Police, the “White Mice” (U.S. Army).

The South Vietnamese military remained the key factor in all Saigonese political calculations; foremost among them were the paratroops, here passing in review at the October 27, 1962, National Day parade. Paratroops spearheaded Diem’s 1955 battle for Saigon, led the 1960 coup, and figured on one side or the other in every coup action except the November 1963 plot that actually toppled Diem (U.S. Army).

Christmas Day 1962. The American Friends of Vietnam were very strong in their support for Ngo Dinh Diem. A principal activist was Francis Cardinal Spellman, a key American prelate. During a tour of South Vietnam’s Mekong Delta, Cardinal Spellman toured the streets of My Tho accompanied by a retinue including American and ARVN officers, clergymen, and notables. To Spellman’s right is Vietnamese III Corps commander General Huynh Van Cao (U.S. Army).

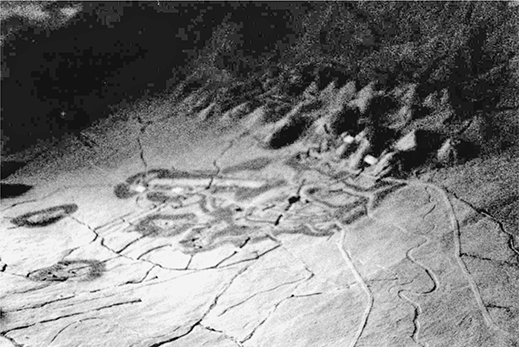

A little more than a week later, on January 2, 1963, General Cao’s troops fought a pitched battle against a much smaller National Liberation Front force at the village of Ap Bac and not only withstood them but inflicted heavy losses and then escaped. The action revealed tactical inflexibility and weak leadership in the ARVN and stunned observers. This aerial view of Ap Bac shows the marks left in the fields by the tracks of the ARVN armored vehicles showing their advances and retreats, demonstrating that they never even reached the village. Two American H-21 helicopters are visible in the center foreground. Five choppers were actually shot down in the action, the worst U.S. loss in the war to date (U.S. Army).

Today’s hero, tomorrow’s traitor, Colonel Tran Ngoc Chau was regarded as an early star of Saigon’s pacification program. Chau led Saigon government efforts in two different provinces, headed a cadre training program closely associated with the CIA, and remained close to several Americans, including the CIA’s William Colby and RAND’s Daniel Ellsberg. Chau later fell afoul of former colleague Nguyen Van Thieu and was abandoned by the Americans during the last days of Saigon. Here, on February 13, 1963, as chief of Ben Tre province, Chau and his staff brief Vietnamese air force pilots on hotspots in their area. His American advisers sit next to him (U.S. Army).

A strategic hamlet in Long An province in the spring of 1963. The defenses of this typical village position, clearly insufficient to resist any serious attack, were built around one of the old French guard towers that dotted the countryside, considered death traps in the French war. Hanoi’s fears of the hamlets were real but exaggerated. The most dynamic U.S. pacification program at the time, the strategic hamlets were controlled by Diem’s brother Ngo Dinh Nhu. The American solution for the military deficiencies of the hamlets was to equip them with radios to call for help. The U.S. 34th Signal Battalion installed the radios in Long An (U.S. Army).

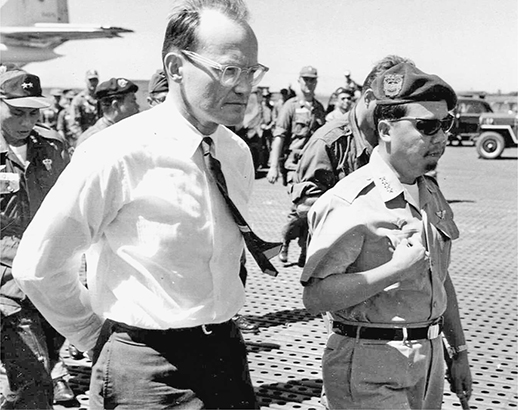

A fateful day, February 7, 1965, when NLF local troops shelled the airbase at Pleiku. Here McGeorge Bundy, flanked by Saigon military strongman General Nguyen Khanh, visit the stricken base. Khanh, who wielded his officer’s stick like a baton, was hardly ever without it. Bundy was sickened by the attack. Thinking Hanoi directly responsible, Bundy recommended—and President Lyndon Johnson approved—bombing North Vietnam (U.S. Army).

The American ground war followed swiftly upon the bombing, with U.S. troops flooding into South Vietnam starting from the summer of 1965. Taken from a helicopter lined up to land on the tarmac just visible at the bottom, this picture of An Khe taken in August 1965 shows the beginnings of what became the huge rear base of the 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile). The division’s units began staging through An Khe about two months subsequent to this photograph (U.S. Army).

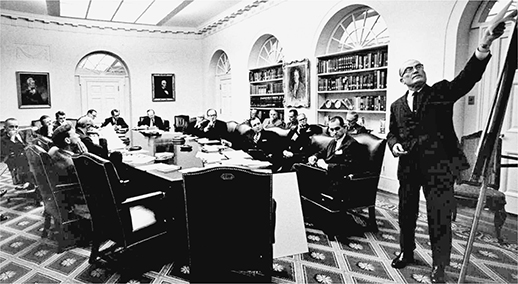

Planning the Vietnam War became a constant concern for President Johnson and his National Security Council. Here, on January 29, 1966, LBJ reviews peace feelers plus data on North Vietnamese infiltration during the Christmas bombing halt and considers fresh military actions. Army chief of staff General Harold Johnson proposes—and he uses the word explicitly—a “surge” of additional troops. NSC staffer Chester Cooper changes the easel display as the president looks on. Johnson is flanked by Dean Rusk and Robert McNamara. McGeorge Bundy sits at the far end of the table, and Vice President Hubert Humphrey is across from LBJ. CIA director Richard Helms is in the end chair left of Cooper (LBJ Library).