Pollitos

I feel a gentle brush against my forearm. I open my eyes. Gladys is looking at me with her index finger pressed to her lips. She’s lying at my side, holding Huckleberry Finn. She opens the book, grabs the pencil folded inside, and writes in the margin of one of the pages.

Hi :)

She hands me the pencil. I write back.

Did you sleep?

We pass the pencil back and forth, filling the slender margins of many pages.

A little. No pillow. Oh, and sand and it’s a million degrees. Sorry I woke you. I don’t feel like I can talk to you when he’s awake.

She turns the book so the arrow points to Marcos. He’s sleeping.

No kidding. This is awful.

I know. Nobody is talking! I want to talk with you. I miss talking with you.

Me too.

I’m scared.

Me too.

And thirsty. I bet I know what you’re going to write…

I smile and mouth out, Me too.

I read what you wrote in here. I liked it.

I blush, trying to remember what I scribbled down while I was borderline delirious.

Thanks. I didn't mean for anybody to read it.

I figured that. But “you have to know when to break the rules.”

Ha, ha.

I want to get to know you better. I like how you think, Pato. You’re not like the others.

??

You think. Do you ever get the feeling you were born in the wrong place?

No. You do?

Yes!

Why?

My mom wanted to be a doctor when she was little. When she grew up, she sewed clothes. Dreams don’t happen there.

Is that why you want to be a doctor?

Maybe. I know that I say I want to be a doctor, but I’m not sure.

So what do you want to be?

She blushes and hesitates. I grab the pencil back.

I'm going to guess. What do I get if I'm right?

I have something for you. A gift.

An artist.

She unfolds a small scrap of fabric torn from Marcos’s jeans. Weaved into the cloth is a variety of plant stems, twisted together in an elaborate design, with varying shades of desert green and brown ducking in and out of each other amid the dark blue of the jeans. It’s beautiful.

She motions for my hand. I hold it in front of her. She wraps the band around my wrist and secures it by tying together blue strands that extend from each end.

Wow! When did you make this?

Yesterday. When you were lost.

It's amazing. Where did you find all the plants?

They’re everywhere. You just have to look. The world is amazing. This has six different plants. I needed the jeans to hold it together.

I love the blue in it.

Thanks.

I guess you proved my point. You should be an artist.

It’s a hobby. It’s not a job. Not where we’re from anyway. You work in a factory, you work in a field, you sew dresses. You work. You don’t play with colors and call it a job.

Who told you that?

How many artists do you know?

None.

Exactly.

But that doesn't mean you couldn't do it. Look what you made in a place where there's NOTHING. You're incredible. People like you go to college. They move to bigger cities. Your cousins in Puebla did that, right? You could study art.

I stop and realize that I’m writing about where we’re from as though it still exists for us. It’s hard to let go even when the loss is all I can think about. I twirl the pencil a few times and redirect the thought.

Besides, your mom's work was art.

Thanks. I think she saw it that way. It was the best she could do with what she had. And maybe you’re right. Maybe I could have left. Do you ever look at the stars and wish you could go there?

All the time.

Don’t you think it’s funny that people think that, and then they never leave the place that they’re from?

I start to write and notice that she’s wiping at tears.

What's wrong?

It’s sad to think that my whole family had to die for me to have the chance to leave. If they hadn’t, I would have stayed there. Maybe I could have left, but I don’t know that I would have. I might have stayed and sewn dresses. Not become an artist. Or a doctor. Or whatever. Now, I feel like I really need to make it. My life can’t end here. It’s got to count. For them. For my mom especially. Because she never had that chance.

I think you'll be a great artist. I think you're already a great artist.

See what I mean? I like the way you think. What about you? What do you want to do?

??

No idea?

It’s my turn to tear up, but I hold it back.

I always thought I'd work with my dad. Now I don't know what to think.

I’m sorry. Do you believe what Marcos said?

I wish I didn't.

Your dad will always be the person you want to remember him being.

Have you been talking to Sr. Ortíz?

??

Thanks.

We’re starting over. You can be anything you want. So…

I'll get back to you on that.

Okay. Do you think we’ll make it?

Yes.

Are you lying?

I hope not.

Me too. We need to think positively. Maybe we should promise each other that we’re each going to make it through.

I promise.

Me too. There! Whew…

I smile.

And when we do, we have a small problem. I need your help.

??

Marcos thinks we should split up over there. He says that La Frontera might be looking for us on the other side and that splitting up will make it harder for them to find us.

I don't want to leave you.

:) Me neither. We need to change his mind, but don’t say anything to him about this! He’ll get mad, and everybody is already mad at everybody (except Gladys and P-P-Pato).

Pato!

:) Let’s try to talk about things that will work best when we all stick together. Like renting an apartment, maybe. It’s cheaper with four people. We need to be smart. We can convince him.

I like the way you think.

She leans over and gives me a small kiss. As she pulls away, I see Marcos. He’s looking right at me, with eyes narrowed like spears. He rolls over to face the other direction.

• • •

“What happens if we go too far north from here?” Marcos asks.

It’s nearly dusk. We have a little more than a liter of water left. Because of this, we’ve decided not to walk until the sun is down.

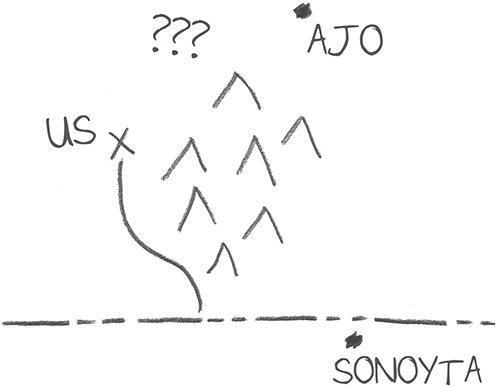

“I don’t know. We might miss Ajo,” I say. Because I spent an extra ten minutes with the letters and can find the North Star, I’ve somehow become the navigation expert. I’ve drawn the most basic of maps on a mostly empty page of the book to help lay out what little I know…or think I know.

“And if we miss Ajo?”

“More desert, I’m guessing.”

“So, you think it’s on the other side of the mountains?”

“Probably. But I don’t know. Maybe they turn. Or maybe there’s a break in them. They didn’t talk about climbing over mountains in the letters.”

“That’s because they weren’t chased out of town, so they started out to the east of them,” Marcos says.

“Maybe. We haven’t seen the lights at night, so I’m thinking they’re blocked out.”

“You and your Ajo lights,” Marcos says.

“I’m just trying to help,” I say.

“And I’m just trying to make sure we don’t walk off into the desert with one liter of water.”

“We’re not going to make it out if we don’t find water.”

“Tell us something we don’t know,” Marcos says.

“Give him a break. He’s only trying to help,” Gladys says.

“Great. Side with your boyfriend.”

“Nobody’s siding with anybody. We’re trying to figure out what to do,” she answers.

“Well, it doesn’t feel like we’re figuring much out.”

“I’m guessing we hiked about fifteen kilometers the first day, then another fifteen yesterday,” I say. “We’re about halfway there. Which means we can walk for another night along the mountains to see if there’s a better place to cross.”

“And water?”

“Your guess is as good as mine.”

“Great.”

“Hey,” Gladys says. “We’re all in the same situation.”

“Then maybe not all of us get it. We have one liter of water. That’s not even going to last until midnight. And then, we die. We need to get out soon.”

“That’s what I said,” I say.

“Well, you’re not acting like it’s a big deal.”

“What do you want me to do?”

Marcos bangs his head against the tree. “I don’t know. And it doesn’t matter. It doesn’t look like we’re getting out of this place.”

Arbo starts to laugh.

“What?” Marcos asks.

“We finally agree on something.”

“And what’s that?”

“We’re screwed.”

“I thought we were dead once,” I say. “And we’re not. So we still have a chance.”

“Whatever,” Marcos says. “Let’s walk.”

• • •

Marcos packs his bag. Gladys sits, entranced, staring out into the sunset, as though she’s enjoying it for the last time. In front of her is something new she’s trying. It’s a sand-scaped scene, but it springs up from the ground. A small collection of twigs, shrubs, bulbs, and other bits of nature are carefully stacked onto her three-dimensional canvas.

A tiny desert flower bulges out of the middle. As the sun drops from view, I watch her cover the petals with sand.

Marcos walks over to her.

Taking advantage of our brief separation, I pull Arbo aside.

“Hey, are you okay?” I ask.

“No, Romeo. I’m not. We’re about to die.”

“I thought you said you were okay about Gladys.”

“I am. I don’t know why I said that. I’m just…”

“You’re what?”

“Done. I don’t even care if we walk,” he says.

“You want to sit here and die, like we were doing before?”

“That’s fine by me.”

“You want me to pee on your head now or later?”

I don’t even get a smirk.

“Whenever you’re ready.”

“It doesn’t change who they are, you know,” I say.

“That’s a lie. It changes everything. Do you know why everybody died? Almost forty people? My whole family? Your whole family? Our friends? Other families? Because of my dad.”

“And mine.”

“Fine. And yours. Our dads. Our narco dads.”

“They weren’t selling drugs, they—”

“I don’t give a crap. They were in business with them. It was dirty money. Everything we had…dirty. I’m glad it’s gone.”

“No you’re not,” I say.

“Maybe you’re not, but I am. I’m done with it.”

“What would Revo tell you right now, Arbo?”

“Revo’s dead.”

“What?”

“You know what Revo did?”

“No.”

“He fought bad guys.”

“Okay.”

“Well, they won. Actually, they were winning all along, and I had no idea.”

• • •

It’s eleven o’clock. We haven’t had a sip of water since we started walking three hours ago. Marcos carries our remaining bottle in his pack.

The moon, dipping behind a mountain, presses us to an unsustainable pace, as we try to make as much progress as we can while we still have some light. My body is as devoid as the dim shadow lurking beneath me.

“There’s no point in killing ourselves before we run out of water,” I say.

“We can make it a little farther,” Marcos answers.

We slog along for another minute or two.

“I can’t do it, Marcos,” Gladys says, stopping. “I need a sip.”

“You know what, fine. I’m not the jefe here. You’re all your own bosses. If you want water, bottoms up. Make it last however long you want.”

He lets his pack fall to the ground. He puts the flashlight in his mouth, pulls the bottle of water out along with three empty bottles, and carefully fills them each with the same amount.

We all take sips, except for Marcos, who turns the light on his leg to inspect it. If it’s still bothering him, he hasn’t let any of us know.

I hold a small swig in my mouth and slide my tongue around, savoring the smooth glide across my teeth. I allow a portion to drop down my throat. I can feel it start to trickle downward before it’s fully absorbed. It never makes it past my neck. I swallow the rest and exhale in delight. Then, as quickly as the relief arrived, it disappears. My mouth turns pasty again, and I eye the bottle, realizing that I could chug all that’s left and still feel as dried up as the wilted bonds that are holding us together. I take one more tiny pull and hold on to it for even longer than last time.

Marcos tugs at my shirt.

“Ven conmigo por un minuto,” he says.

I follow his instructions, walking a short distance away with him. We stop. He leans in close and speaks in a hushed voice. “If I see you kiss my sister again”—I can feel his breath, hot and putrid, punch against my face as he speaks—“I’ll pick you up and throw you into a cactus.”

He doesn’t wait for me to answer. He turns and walks back toward Arbo and Gladys.

“Hey! We’re not done,” I say in a full voice.

He stomps back toward me. “Keep your voice down, and yeah, we are done.”

“No. We’re not even close. I’m not going to wait until your back is turned to talk to her, I’m not going to act like nothing is going on, and if I want to kiss her, I’ll try to do it while you’re not looking, but I’m going to plant one on her. You know why? Because we’re dying, and this is all we’ve got. A few hours. A day maybe. And I’m done pretending.” My voice has gotten louder by the word. By now, there’s no doubt that Gladys and Arbo can hear everything. “So if you need to throw me into a cactus to speed up the dying and prove what a tough guy you are, then go for it. Pick one. They’re everywhere.”

He takes another step toward me. His nose nearly touches mine. The whites of his eyes hover like two rings, encircling the darkness inside.

“Don’t. Push. Me,” he says, making each word stand on its own, fully pronounced in a thick, slow, low voice. “I’m her brother, and I’ll do what I have to do to protect her.”

“I know,” I say. “And I would too if I were you. But what I’m saying is you’re not protecting her. You’re hurting her. Can I ask you a question?”

“Go for it.”

“How many boyfriends has she ever had?”

“None.”

“And have you ever had a girlfriend?”

“Yeah.”

“How many?”

“A few.”

“I’m sure it’s more than a few. How good does it feel?”

“What do you mean?”

“I mean, how great does it feel to have another person who wants you like that? Who loves you without you being family. Who tells you how great you are.”

He doesn’t answer.

“She’s never had that. Neither have I, for what it’s worth. Not like this. And I think she deserves it. Before she dies. Before I die. Before we all die.”

Again, he doesn’t answer. He stares, long, like he’s waiting for me to look away at some point. I don’t.

He turns and walks back to the others.

I follow.

A soft hand reaches out from the darkness and squeezes my palm.

• • •

I don’t know what time it is. It doesn’t matter. It’s the middle of the night. The moon is gone. So is my water. I suck the air out of the bottle, trying to breathe in the moisture. Others do the same.

Marcos whispers something and passes his bottle to Gladys. She pushes it away. He shoves it back toward her. Neither will take the final sip.

We rest for a few minutes, then stand on shaky legs and press on.

• • •

Arbo is the first to drop.

“I can’t keep going. My legs are cramping.”

None of us complain. We collapse alongside him.

“Maybe we’ll be able to see something when the sun comes up…” Marcos says. His voice fades in a way I’ve never heard it do. I don’t know what he’s hoping to see.

I reach into the darkness and grab Gladys’s hand. She clutches back, and I close my eyes. If we’re being watched, I don’t want to know.

I let go of everything and drift into the night. I dream of a thunderstorm. A magnificent, pounding, rage of nature with gusting walls of water that slap against me, seeping into every pore of my body. As relief gushes in, a bolt of lightning explodes into the middle of us.

“Did you hear that?” Marcos whispers.

I wake in the windless night air. The first thing I feel is my thirst returning. It’s not a longing. It’s a pain. Then I hear the footsteps. Not right next to us, but not far away.

“What is it?” Gladys asks.

“I don’t know,” I say. “People.”

“Shh,” Marcos says.

We raise our heads and peer into the darkness. Shadows move. Many shadows. There’s a flicker of light. Only for a moment, followed by a soft whistle. The footsteps stop.

“Shh,” Marcos repeats, though so softly that I can barely tell he’s doing it.

Did they spot us? Who are they?

My own quickening pulse fills my ears, blocking out their murmurs.

We lie low for an anxious stretch of minutes. Then one clear voice rises from the group.

“To the right. A la derecha.”

The footsteps resume—and become louder. We press our bodies low to the ground.

They pass within five meters and continue onward, oblivious to us. They march toward the mountains.

“Who are they?” Arbo asks as soon as the last of their group goes by.

“I don’t know, but they seem to know where they’re going,” Marcos says. He starts gathering things.

“Do we follow them?” Gladys asks.

“It’s that or lie here and die,” Marcos answers.

I turn to Arbo for his reaction. He slowly pushes himself to his feet. The rest of us do the same, as quietly as possible.

“Who do you think they are?” Gladys whispers to me.

“Un guía con pollos,” I answer.

“What?”

“People like us, but they have someone showing them the way.”

Following them is not as easy as we might have thought. We need to stay back far enough that we are neither seen nor heard, but close enough that we don’t lose them in the darkness. And we can’t use any light to guide us, not even Arbo’s watch. We’re back to Marcos waving a stick out in front of him, stopping and turning suddenly each time he strikes a target.

It’s a sluggish pace, but fortunately the group is moving slowly as well.

My body still feels shriveled and empty, but the belief that we’re now moving in the right direction lifts my spirits enough to lighten my feet. We don’t talk, but I can sense that the rest of the group is feeling the same.

Soon the mountain begins its steep slope, and we all slow to a crawl.

“Vámonos. Un poco más. Then we’ll go back down.” The occasional voice echoes off the rocks, giving us clues as to what lies ahead.

Eventually.

Un poco más is like mañana. It’s an intention, not a reality. An hour later, we’re still climbing.

• • •

Dawn breaks, and with it, we lose our cover. We watch the group ascend in the distance until the guía finally delivers on his promise. The group drops over a ridge and out of sight.

We hustle up the steepening rise, winded but propelled forward by the fear of losing them. As we approach the ridge, each cautious step reveals a little more of what lies ahead. It’s not what I expected. We are at the top of a hill, with more mountains beyond.

On the other side of our hill, we see the group snaking down toward an empty riverbed that forges a winding trail through the peaks ahead. I stare at the bed, wondering when, if ever, it brings water.

We rest until the group reaches the riverbed, turns around a bend, and moves out of view. Again, we follow their path.

All around us is evidence that we are going the right way—trash. It’s clear that the group in front of us is not the first to pass along this ravine. Plastic and foil dot the landscape just as the prickly plants do. Empty soda cans taunt us. Shreds of other debris peek out of the sand in tattered strands. All of it looks dull and bleached, as if it were left here a hundred years ago. It’s a cruel reminder of how quickly the desert destroys everything.

• • •

Walking in the riverbed feels both freeing and vulnerable. For the first time since we started our trip, we can move forward without fear of being jabbed or scratched, and we can take more than ten steps in one direction without having to turn. If we had any water left and weren’t quickly withering away, I might even call the hiking easy. But it comes at a price. We are openly exposed to anyone in the area above, and to the group ahead of us if we’re not careful. Even more than being spotted, we fear that the group will turn away from the riverbed and quickly disappear in the mountains. It’s unlikely, but so was our finding them. Probability doesn’t mean anything out here. You get one chance and you hope you get lucky. This is our opportunity to be led out of this death trap.

• • •

The fire returns as it does every day, with an explosion of light and heat as the cloudless sky slings the sun over the mountains. The group stops, and we do the same. We’re three or four hundred meters away from them, peering around the thick cacti and sprawling shrubs that line the edge of the riverbed. I try to count them. I think there are seventeen people total.

The cleverness I felt when I created our tree shelter disappears as we watch them unfold several small, tan tarps and drape them across a pair of cholla cacti, a towering mass of sprawling thorns that looks like what might happen if a cactus and a tree were to have a baby. They use its thick spines to anchor the tarps in place, giving them a broad swath of shade. Then, as we did, they huddle beneath it, too close for comfort, too hot to care. They pass jugs of water around and take long pulls on them. It’s tormenting.

We backtrack until they’re out of view and set up our own shelter.

“We need to make sure they don’t leave without us,” Marcos says.

“I don’t think that’s our biggest problem,” I say.

He doesn’t respond. Nor does anyone else. They don’t need to. I look at Arbo. He’s collapsed on his side, resting for now.

For now.

Gladys does the same. I feel the tickle of a headache in the back of my skull.

We won’t last the rest of the day.

“We need water,” I say.

“Okay. You have any ideas?” Marcos asks.

I turn and nod my head in the direction of the group.

“You think they’re just going to give it to us.”

“I don’t know what other option we have.”

Silence.

“We could steal it,” Marcos says.

“There are seventeen of them,” I say.

“They need to sleep. We could go in a couple of hours.”

“They won’t all be sleeping.”

“They’ll be trying to. Just one of us will go. I’ll do it.”

“Güey, they’ll catch you, and then we’re really in trouble,” I answer.

“At least my way, they might not catch us.”

“We can’t steal their water. What would you do if someone stole our water?”

“And what would you do if someone walked up to us and asked for it?”

“I’d say I’d be glad they didn’t steal it.”

I don’t say this. A coarse voice that comes from beyond our group does. We all sit up straight as two men emerge from behind a pair of thick shrubs that shield us.

“Settle down, and don’t move,” one of them says. He wears a sleeveless flannel shirt that’s partially tucked into his pants, revealing the upper half of a pistol.

“Anybody got any water we can have?” the other one asks, smiling through crooked teeth. He has a tattoo of three parallel bars that run up the side of his neck.

None of us speak.

“So, I’ll take that as a no, huh? You want to tell us why you’ve been following us?” Flannel Shirt asks.

“We’re lost,” Marcos says. “We followed you because you look like you know the way out.”

“We do. That’s why you pay a guía to take you across. Anybody here a guía?”

We shake our heads.

“Every pollo pays the price… It’s just a question of when and how much it costs you.”

“I have money,” Marcos says.

“Then why didn’t you get someone from the start?”

“I don’t have that much money.”

“So, you don’t cross. You wait until you do. There’s a system, güey. You cross, you go through us. We’re the ticket to the other side.”

“Like I said, I have some money. Do you want to talk?” Marcos asks.

“Okay, güey. Let’s deal. What do you have?”

Marcos stretches for his bag. Both men reach for their waistlines.

“Give me the bag. I’ll open it.”

“It’s my bag.”

“If we wanted to steal your bag, you’d be dead by now.”

Marcos tosses his bag to them, a touch firmer than is necessary.

“It’s in the pocket on the inside,” Marcos says.

Flannel Shirt fishes out a small roll of money, counts it, then starts to laugh and shows it to Neck Tattoo.

“You want to cross for this? We can take you to the other side of the riverbed,” he says, pointing about fifty meters away. More laughter.

“That’s all we have,” Gladys says.

“Do you see all those people over there?” Flannel Shirt asks.

They are blocked from view, but that’s not the point. We nod.

“Each of them paid a thousand dollars. That’s more than twenty thousand pesos.”

“Can we just buy water?” I ask.

“And what happens when you try to follow us. All sloppy-like, and la migra finds you…then us. What happens then?”

“We won’t follow you.”

“There’s only one way to go from here, güey.”

I don’t know whether it would help us, but I’ll admit to wishing we had Marcos’s mota right now. I wonder if Arbo feels the same.

They back away and talk quietly to each other.

“Stay here,” Flannel Shirt says. He walks back to the group. Neck Tattoo stays with us. He squats in the thin shade of a low bush a few paces away.

“How old are you guys?” he asks.

“Nineteen,” Marcos says.

“All of you?”

We nod.

“You don’t look nineteen. You look younger,” he says.

“So do you,” Marcos says.

He doesn’t look much older than us, but the bars on his neck add a few years. Maybe that’s the idea. I wonder what they mean, if anything.

“You. What happened to your eye?” he asks Arbo.

“He punched me,” Arbo says, pointing to Marcos.

“Mr. Tough Guy, huh?”

“You want to find out?” Marcos asks.

He shoots Marcos an annoyed expression and quits asking questions. Several minutes pass in silence, then we hear footsteps. A different man appears. I recognize him from tracking the group—he’s the one I thought was in charge.

He’s probably twenty-five. He’s wearing a beige T-shirt with some faded words in English. The stretched neckline of his shirt reveals a thin gold chain with a cross flopped over his neck. He looks us over from underneath a baseball hat pulled down nearly to his eyebrows.

“How old are you guys?”

“Nineteen,” Neck Tattoo says.

“I didn’t ask you,” he says. He turns back to us.

“Nineteen,” Marcos says.

Again, he looks us over.

“Why didn’t you hire someone to take you across?”

“We didn’t have any money.”

“Lots of people don’t. That’s not how it works. You think those people over there have thousands of pesos lying around?” His tone is rhetorical. “They pick beans. They sell tortillas. They borrow the money.”

“So, can we borrow it?” Marcos asks.

He chuckles.

“No tienes ni idea, güey. Did you just ride your bikes to the border and start walking?”

“No.”

“Where are you trying to go?”

“Ajo,” I say.

“Ajo. Ajo. So you do know something,” he says. “Who told you to go to Ajo?”

“We read about it in a letter from a friend who crossed.”

“Did your friend go through a coyote?”

“Yeah.”

“Then why didn’t you, güey?”

“Like he said, we didn’t have the money,” I say.

“But you did have some money, right?” He holds up Marcos’s small roll of bills. “Which one of you had it?”

“I did,” Marcos said.

“Can I talk with you for a moment, in private?”

Even Marcos looks concerned at this request.

“I’m not going to do anything. I swear. One minute and then we come back over here to your friends.”

“What do you want to ask?”

“You’re the money man. I have a couple of questions.”

Marcos stands and they walk aside together. They never leave our sight, but they go far enough away that we can’t hear them.

True to his word, they are back in under a minute. Marcos takes a seat with the rest of us.

“Okay. Let me explain how this works, since you apparently have no idea,” he says. “There are two ways you can get a guía. If you have the money, you pay, and it’s all good. But if you don’t have the money, you ask Sr. Coyote to loan it to you. And he does, because he knows you’re going to repay it. Do you know how he knows? Because he does his homework, and he knows where your family lives. That’s trust.”

He makes a point to look at each of us in turn.

“Can I trust you?”

We all nod.

“I’m tempted to. You look very nice. But to be sure, why don’t we play a game called Confianza. It’s an easy game. It’s one question. Here’s how it works. Everybody, point to your friend, the money man.”

We all raise unsure fingers.

“Now, on three, everybody say his name.”

Crap.

Marcos looks down. I know him well enough to recognize that look. He’s been had. And so have we. At this point, we don’t have much choice. Either we make up three names which won’t match, or we all give the same name and hope that three out of four is a good enough answer. I hope Arbo and Gladys are thinking the same.

“One, two…”

“Marcos,” Arbo and I say. Gladys says nothing.

He looks at Gladys with a stern eye.

“Marcos,” she says in a low voice.

“Ah, Marcos. Everybody says Marcos…except for Luis.”

“It’s not Luis. It’s Marcos,” Marcos says.

“Why would you lie to me?”

“I don’t know you.”

“And yet, you ask me to help you.”

Marcos gives a pride-swallowing nod.

“Let’s play the game again,” he says. “Now everybody point to him.” He points to Arbo and we have no choice but to say his name.

Soon, we’re all named.

“And on three, where are you from?”

This could get very ugly, very fast.

“Now, let’s point again and tell me how old you are…”

Very, very fast.

“And where are your parents? On three…one, two…”

None of us answer this one.

“I said, ‘Where—’”

“They don’t know we came,” I interrupt.

He stares at me and I stare back at him. As I do, Flannel Shirt returns. He’s carrying a jug of brownish water.

“That’s enough trust for now. You need water.”

“Why is it brown?” Arbo asks.

“We hit an old well yesterday. It’s not the best, but be thankful it had water. If it hadn’t, you wouldn’t be getting anything.”

“So, you’ll guide us out?” Marcos asks.

He nods back to us.

“How much?”

“We’ve got a couple of days. We’ll figure it out,” he says.

He turns and walks away. As he does, he says, “Come on over. There’s a tree you can put your stuff on. But be quiet, our other pollitos are sleeping.”