For endurance athletes, a little bit of sprinting goes a long way. The occasional short-duration workout, performed only during high-intensity training periods, can generate exceptional improvements in endurance performance. Sprinting improves cardiovascular function, helps muscles buffer lactic acid, and extends “time to fatigue” markers at all intensity levels. Sprinting elicits a spike of adaptive hormones into the bloodstream, delivering a potent anti-aging effect. Sprinting improves resilience to physical (muscle contractions) as well as psychological fatigue, allowing you to go longer and faster during endurance efforts. Sprinting, especially high-impact sprints (running), strengthens muscles, joints, and connective tissue. Finally, sprinting can get you over the hump with difficult body composition goals by turbo-charging fat metabolism around the clock.

Deliberate and focused warmups are essential to ensuring a safe and effective sprint workout. Endurance athletes might have to adjust their mindsets to minimize the importance of suffering and enduring and instead focus on delivering high-quality explosive performances, only when they are 100 percent rested and motivated for peak performance.

Each sprint you perform should be of consistent quality—a similar measured performance and perceived exertion level. If you slow down significantly, or have to work significantly harder to maintain the same performance standard, it’s time to end the workout. A good general recommendation for endurance athletes is a sprint workout consisting of five repetitions of fifteen-second sprints. Rest intervals vary, probably from thirty seconds to one minute, with the main goal of ensuring you are rested and psyched for the next rep!

Stacking an MSP strength training with a sprint session can deliver performance benefits via the concept of postactivation potentiation. You literally “pump up” your muscles and central nervous system by challenging muscles under load prior to sprinting.

Conducting an effective sprint session entails picking the right day (rested?), the right exercise (high impact, unless injury risk or sport goals dictate otherwise), a deliberate, focused warmup, the appropriate number of work efforts, reps, and rest intervals, a deliberate cooldown, and finally recovering completely before the next sprint workout.

BELIEVE IT OR NOT, SPRINTING does have a place in the picture for endurance athletes and even ultradistance endurance athletes. By sprinting, we’re talking about all-out efforts, short in duration and performed only occasionally. When you properly integrate sprinting into your program, you enjoy an assortment of health and fitness benefits as follows:

1. Fitness Boost: Improving your all-out explosive performance stimulates profound physical changes that have a direct application to performance at lower intensities. Modern research confirms that the health and fitness benefits of sprinting in many ways surpass the benefits of cardiovascular workouts that last several times as long. Sprinting improves capillary profusion and mitochondrial biogenesis—building a bigger engine for use at all intensities. Sprinting turbocharges the oxidative enzymes that burn fat and glucose, enhances oxygen utilization and maximal oxygen uptake in the lungs, improves the ability to store and preserve glycogen, improves muscle buffering capacity (the ability to process and eliminate lactic acid and other waste products from the bloodstream), and extends the “time to fatigue” marker at all levels of intensity. After only a few sprint sessions, you’ll be lighter, faster, more explosive, and more comfortable at whatever pace you perform at.

2. Anti-Aging Effect: Occasional short bursts of maximum-effort sprints trigger a cascade of positive neuroendocrine, hormonal, and gene expression events that deliver a potent anti-aging effect. The spike of adaptive hormones like testosterone and human growth hormone that occur in response to sprinting stimulates lean muscle development or preservation, accelerated reduction of excess body fat, increased energy and alertness, enhanced insulin sensitivity, improved lipid profiles, and increased mitochondrial biogenesis. Sprinting also improves cognition and elevates mood by decreasing inflammation in, and improving oxygen delivery to, the brain. High-impact sprinting (running) helps to increase bone density and strengthen bones and connective tissue.

Sprinting stimulates an immediate and significant spike in cortisol, but this is an example of a genetically optimal activation of the fight-or-flight response to support an extreme effort of brief duration. Scientists call the positive effects of a brief natural stressor like sprinting hormesis. Our genes expect occasional short-term shocks, which we can adapt to and become stronger from. Cold-water plunges, relaxing in a sauna or hot tub, or getting some exposure to direct sunlight all deliver a hormetic effect at the proper dosage, but—like chronic exercise—can be unhealthy when excessive.

Once a brief sprint workout concludes, cortisol levels moderate, while the so-called “adaptive” hormones (testosterone, human growth hormone) circulate in the bloodstream and target specific organs to promote enhanced health and vitality and deliver assorted anti-aging effects. Adaptive hormones help preserve or increase lean muscle mass, reduce excess body fat, enhance cellular repair and regeneration, and increase bone density and libido. Testosterone is elevated for fifteen minutes to an hour after intense exercise, while growth hormone, produced in the pituitary gland, sticks around for twenty-four hours. That’s plenty of time for both agents to effect a host of positive changes.

A 2003 study in Sports Medicine lauded the hormonal benefits of intense exercise in general, while taking an indirect dig at chronic exercise: “…the impact of some of the deleterious effects of aging could be reduced if exercise focused on promoting exercise-induced growth hormone response.” A 2003 study in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism said, “…the beneficial effects of intense exercise can mimic the effects of (artificial) HGH treatment.” Indeed, a study in the 2002 Journal of Sports Sciences showed that a single thirty-second cycling sprint increased growth hormone levels by 530 percent over non-exercisers’ base levels. “The harder you work the more you produce,” is the message of a 2002 University of North Carolina-Greensboro study in the journal Sports Medicine, which found that greater intensity of both aerobic and strength training stimulates greater release of HGH.

Testosterone, produced in the testes of males, is considered the quintessential male hormone. However, it is also produced in the ovaries of females and has a similar vitality effect, even though females have only about one-seventh the amount circulating as do men. As you probably know, these vitality hormones decline with chronological aging—the effects of this decline pretty much represent the essence of aging—so you might be particularly interested in nurturing healthy circulating levels of these hormones through exercise and other lifestyle behaviors once you hit the big 3-0 and beyond.

Females might be a little taken aback reading about the importance of their testosterone (and might consider a new quip to yell out the window when victimized by aggressive drivers). Interesting research cited by authors Ashley Merryman and Po Bronson, in their outstanding book Top Dog: The Science of Winning and Losing, indicate that testosterone’s beneficial effects extend far beyond the narrow layperson view that it increases aggression. Merryman elaborates on this concept: “Testosterone is primarily a social hormone, providing the motivation for behaviors that are most valuable—under whatever particular circumstances you are facing—to bring you social status and approval. Sure, sometimes that’s aggression—especially when your social status is being threatened. Other times a testosterone spike can fuel focus, or cohesion within a team.

“For example, when paramedics and firefighters work in an emergency situation, testosterone motivates the firefighter to rush into the building, save the people, and then go back and try to save the goldfish too. For the paramedic, testosterone enables him or her to stay conscientious while treating a victim, taking meticulous notes to assist the doctors when the patient arrives in the emergency room.”

3. Resilience to Physical and Psychological Fatigue: Sprinting trains your brain to become more resilient to fatigue, lowering the rate of perceived exertion at all intensities. It’s like jumping up for the rim ten times while wearing ankle weights, then taking them off and jumping again. You feel like you can fly! This is not superficial commentary; the psychological resilience you develop while sprinting literally makes your competitive pace of five-minute, six-minute, or eight-minute miles seem easier. We’ve mentioned Dr. Noakes’s Central Governor Theory a few times, and it applies here as well. When you train to become competent at maximum output, even for a very short time, you are firing not just your hamstrings but the neurons in your brain—making them more adept at sending signals to generate explosive force and more resilient to fatigue.

But let’s not discount the hamstrings! Over a decade ago, Jens Bangsbo of the University of Copenhagen published research popularizing the idea that muscle fatigue during exercise is primarily caused by a depletion of the minerals sodium and potassium in the muscle cells. Muscles need an electrical charge across the cell membrane to contract effectively, and this requires sodium outside the cell and potassium inside the cell. Sodium-potassium pumps in the cell membranes ensure high concentrations of each mineral and efficient recycling of potassium back inside the cell after each contraction. The sodium-potassium pumps are fueled by ATP, the familiar energy source for muscles during activity.

When you challenge muscles with maximum-intensity contractions, such as when sprinting or strength training, pumps become more effective, leading to improved endurance. Triggering the fight-or-flight response will also turbocharge the sodium-potassium pumps, bringing literal significance to the term “pumped up.” By the way, it’s believed that muscles can contract at maximum force for only around thirty seconds before fatiguing, so your sprint efforts should never exceed thirty seconds—otherwise they are not really considered sprints. This characterization is similar to the commentary about MSP workouts, where you want to “go maximum or go home.”

4. Stronger muscles, joints, and connective tissue: When you put your body under the intense load of sprinting—demands of up to 30 MET, and in the case of running fast, generating five to six hundred pounds of impact force per stride (a thousand pounds if you’re Usain Bolt!)—your body responds during the recovery period by strengthening those moving parts. If you can sprint safely, your injury risk when running at low intensity drops substantially. Obviously, this benefit is maximized when you are doing weight-bearing activity like running. However, even if you’re doing low- or no-impact sprinting (rowing, cycling, swimming, cardio machines), you are still generating much greater forces than during a typical endurance workout, and building more resilient muscles, joints, and connective tissue.

5. “Nothing cuts you up like sprinting”: This is Mark’s favorite spicy, but dead serious, reply at Q&A seminars when people ask how to overcome stalls in weight-loss progress. Even if you are fully fat-adapted through diligent primal-aligned eating, honoring your natural appetite to eat only the calories you need to feel satisfied, and putting in substantial training hours, genetic predispositions and homeostatic drives make it difficult to lose those final few or dozen stubborn pounds. Enter sprinting. Performing at 30 MET sends a strong adaptive signal to your genes to pare away any unnecessary weight—again, to prepare for future (perceived as life-or-death) maximum physical efforts.

While carrying excess pounds through a 70.3-mile triathlon or a 26.2-mile marathon is no fun, extra non-functional weight presents an exponentially greater hindrance to sprinting performance. Watch sprinters perform at a meet or on TV or YouTube and you will quickly realize there is no such thing as excess body fat in their world. It’s simply impossible to train and perform at an elite level (or even a moderate level, like quality college or high school athletes) with excess body fat jiggling along at over twenty miles per hour. Conversely, it is commonplace to see excess body fat crossing the finish line of a triathlon, marathon, or ultramarathon.

In a landmark 1994 study published in the journal Metabolism, researchers found that short, intense bursts of exercise zap considerably more fat than sustained aerobic activity. The explanation, according to Dr. Mark Hyman, the author of Ultrametabolism: The Simple Plan for Automatic Weight Loss, is that your mitochondria, the little engines in your cells that burn calories and create energy, run hotter all day after intervals. You metabolize fat at an accelerated rate for up to twenty-four hours after a sprint workout, according to a 1985 study in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition.

We’re not talking about totally revamping your program and your competitive goals and running out to buy spikes and a form-fitting body suit. The idea here is to integrate just a bit of sprinting into your game and enjoy huge fitness benefits. You conduct sprint sessions only during intensity phases, and only when you feel 100 percent rested and energized to deliver a maximum effort. The total duration of your sprint workouts, including warmup and cooldown, will be no more than twenty minutes, with the work efforts totaling up to only a handful of minutes.

Believe it or not, going out and doing four to six hundred-meter sprints is a perfectly respectable workout for an endurance athlete. That’s only a couple minutes total of hard work, and the entire session might take only fifteen to twenty minutes. A workout like this will elicit the aforementioned spike of adaptive hormones, turbo-charge fat metabolism, and condition the brain to become more comfortable with lower-intensity endurance efforts, but it won’t blow out your stress hormones for three weeks like a block of excessive volume or black hole intensity zone training will. It also won’t ruin your work productivity that afternoon like a grueling 5:30 a.m. Master’s swim session of 4,500 meters might.

Despite the extreme physical effort, you should feel pleasantly pumped after a sprint workout. You probably won’t feel like going out for a fifty-seven-mile bike ride in the hills right afterward, but you can definitely go about your daily business. You’ll likely feel some moderate to significant next-day muscle soreness, especially early into your sprinting practice, and should consequently take a day or two of recovery, where you either don’t exercise beyond walking, or are certain to keep your heart rate in the recovery zone of 65 percent of maximum heart rate or lower.

It’s important that your Type-A, endurance-oriented brain approaches sprint sessions with the proper perspective. More is not better when it comes to sprinting—and that goes for workout frequency as well as number of repeats. The goal is to signal optimal gene expression and the profound physical and psychological adaptations that come from 30 MET efforts.

Sprinting comes with a high risk of injury, especially if you are a novice and even if you are highly experienced. The first and foremost rule is to only attempt these sessions when you feel 100 percent rested and energized to deliver a maximum effort. If you have low energy at rest, elevated stress factors in daily life, lingering soreness, or injury hot spots, don’t even consider sprinting until you are champing at the bit with a green light on all systems checks.

Besides the injury risk, central nervous system fatigue is a major factor in sprinting, as well as high-intensity strength training. It’s a major effort for the brain and the nervous system to fire those muscles at maximum capacity and produce maximum force, even for only a short time. You can definitely burn out on high-intensity training, just as you can with chronic cardio, if you aren’t extremely vigilant about not only muscular fatigue (soreness, weakness), but also central nervous system fatigue.

Sprinting in a pre-fatigued state not only risks poor performance and muscle damage, but literally slows down your central nervous system’s messaging process, according to a study by periodization guru Tudor O. Bompa, PhD, in his book Periodization Training for Sports. That means that even if you run the same speed as usual, your fatigued body can’t accurately process that effort fully, so you don’t get as much benefit from the session as you should. It’s like studying your tail off to score 100 percent on a test, but only getting credit for 90.

Technically, here’s how sprints improve you: When you sprint, you force the billions of neurons of your central nervous system (CNS) to process messages and motor responses faster and more accurately. Information signals are transferred from muscle to brain to muscle by moving from “receptor” cells to “effector” cells through the CNS. To move the body as fast as possible when sprinting, the speed of this signal itself also needs to be super-fast in order to recruit the optimal amount of fast-twitch muscle fibers for the job. Therefore, an athlete’s receptors and effectors need to be primed for action—“optimally excited and uninhibited,” explains Bompa.

Owen “O-train” Scott, an elite California high school sprinter and running back, primes his central nervous system for maximum effort with explosive hops. Thanks to his efficient warmup, he threw down an 11-flat 100 meters after the photo was snapped.

The trouble is that fatigue will slow down the ability of the receptors and effectors to get excited and uninhibited, particularly those within fast-twitch fibers, which fatigue much more rapidly than the oxidative slow-twitch fibers that power aerobic workouts. Bompa says you can identify central nervous system fatigue by the subjective sensation of “quickness.” If you feel quick and springy, this indicates you’re rested and ready. Check out sprinters as they assemble in their lanes before receiving the command to enter the blocks. Nearly all of them perform the same preparatory exercise of a series of explosive jumps in the air, where they bring their knees up high as if trying to land on a plyo box. If your feet feel too slow in leaving the ground as you run, your speed in lifts is lagging, or your ability to hit a tennis ball or other sports skill is off, you probably are fatigued.

When you feel rested and ready to go, it’s imperative to create a carefully structured, high-quality workout, featuring an optimal warmup period, preparation drills that reinforce good technique and get the central nervous system excited and uninhibited, a main set of all-out efforts with plenty of rest to ensure consistent quality of the efforts (details shortly), and finally a deliberate cooldown to smoothly transition back to a resting state. This will minimize the stress of the session and promote a speedy recovery.

Sprinting effectively requires that you switch hats and lay aside many of the principles that frame your endurance workouts. Intervals, tempo sessions, and time trials are distinct workouts with different objectives from a true sprint session. These anaerobic endurance sessions, with work efforts ranging from one to ten minutes on minimal rest intervals, are designed to get you comfortable with performing at or near your anaerobic threshold—as you would when racing for an hour or longer. You are training your brain and body to keep pace despite lactate accumulating in the bloodstream. You have to bear down, stay focused, and stay with the group despite your legs and lungs begging for respite.

With sprinting, it’s time to don your Usain Bolt cap and think about performing instead of suffering. Here’s a guy who will travel across the globe and pack a stadium full for a single glorious effort lasting less than ten seconds. Not a bad way to earn a few hundred grand, eh? With your sprint workouts, take your time with careful warmup and drill preparations, and adequate rest between work efforts—just like MSP sessions in the gym. Have some fun stretching in the sun, chatting with your workout mates, and generally operating at a relaxed pace instead of worrying about workout duration on the stopwatch, mileage on the GPS, heart rate zones, and how much raw work you can squeeze into whatever time you have allocated for a workout. Leave the toys and the OCD noise at home and go to the track or chosen venue focused on opening up the throttle and having some fun!

Brad hanging out with—okay, photobombing—some Olympic gold medal sprinters during their track workout at UCLA. These elite athletes spend two or more hours at the track most every day. They’ll deliver only a handful of total minutes of serious hard work, while the rest of the time is devoted to jogging, stretching, mobility exercises, preparatory drills, chatting with Brad, and generally moving at a leisurely pace, except when the coach blows the whistle for another repeat!

Along those lines, if you feel a twinge in your hamstring or other signs of suboptimal function, pull the plug on the session like a true Olympian. Yep, sprinters pull out of their races all the time, even as late as when they settle in the blocks, take a couple practice starts, and feel a small disturbance in their motor patterns. Just like a jet airplane or a rocket ship, these finely tuned explosive performance machines will not operate unless every single check light comes up green.

Since the focus with sprinting is on developing explosive power, the duration of the recovery interval (how long you wait to start your next effort) should be sufficient enough for respiration to return to near normal, and for you to feel mentally refreshed enough to tackle another effort. It is common for athletes even at the elite level to experience mental fatigue along with physical fatigue during a difficult all-out sprint session, due to the incredible demand that all-out efforts place on the central nervous system. Consequently, in addition to physical markers such as respiration rate and muscle fatigue, you should be vigilant about mental fatigue. If you have difficulty focusing, concentrating, or even keeping your balance during a walk recovery interval, this is an indication that the nervous system is fried and that further sprint efforts are unwarranted.

Each sprint should be similar in both measured performance (e.g., time over a certain distance) and perceived effort level. Consider the example of a sprinter deciding to conduct a workout of five times hundred-meter sprints at consistent quality of performance and effort. On her first effort, she covers the length of a football field in twenty seconds. Full recovery should be taken by walking and light jogging (perhaps back to the original starting point at the opposite end of the field) until respiration returns to near normal. Each subsequent effort should be delivered at a similar effort and also be around twenty seconds.

As the workout proceeds, a slight attrition in performance (slower time) is allowable and expected. In this example, the measured performance is the time it takes to run the length of the field; perhaps this athlete will clock twenty-one seconds on her third and fourth efforts. Measured performance can also include running or cycling uphill for twenty seconds and trying to make it to the blue house on the right each time, or performing on calibrated fitness equipment in the gym (e.g., cycling for twenty seconds at 25 mph or at a certain wattage output).

As physical and mental fatigue accumulate, it will be difficult to deliver a consistent quality effort on subsequent sprints. In the runner’s example, a couple of scenarios might unfold after working hard on four efforts: First, delivering another twenty-one-second clocking will require significantly more effort—blowing out their engine with an “eleven” effort on a scale of one to ten, just to try and hit twenty-one again. This is not advised because it can result in exhaustion, extended recovery time, overstimulation of stress hormones, and increased risk of injury.

The ideal sprinting strategy is to deliver a controlled maximum effort—preserving your form, rhythm, and focus for the duration of each effort—not face-planting at the finish line. The second scenario is that another run at consistent effort will result in a substantially slower time than twenty-one seconds. When effort level is maintained but performance drops off markedly, it’s a sure sign that it’s time to end the workout and thereby preserve its quality and intended training effect.

Sprint workouts are not meant to be a steady march to exhaustion. The romanticized image of an athlete puking trackside after pushing through an extreme sprint workout is not aligned with optimal gene expression or sensible fitness progress. Consistent quality should be the foremost goal of your sprint sessions. Even if you don’t measure your time or performance carefully, it can be very effective to regulate your perceived exertion on each effort so that your last effort isn’t vastly more strenuous than your first, and to be aware of any attrition in performance (slowing down from fatigue).

Remember, sprint workouts are always supposed to be challenging, high-quality efforts—there is no such thing as a “moderate” or “light” sprint workout! If you notice on your first couple of sprint efforts that your body isn’t responding in the expected manner due to fatigue, you should end the session and attempt another sprint session when your energy and motivation levels are optimal. If you learn from experience that times drop off after the fourth or fifth repetition as in the aforementioned example, you can design future workouts with appropriate target times and number of reps.

As your fitness progresses, you should aspire to increase speed rather than add more repetitions. The sprinter doing five times a hundred yards in twenty seconds may one day improve to seventeen seconds for five efforts, but there is no need to ever escalate to ten repetitions. Going for quantity instead of quality will increase the risk of entering a chronic pattern and compromise the intended purpose of these types of workouts. As mentioned in the MSP discussion, you don’t want to get into a “blended” workout situation where elements of endurance start entering the equation—too many reps, not enough rest, and so forth.

Recall that an anaerobic period must never last more than four weeks, and that Dr. Phil Maffetone suggests that best results come from anaerobic blocks of only two to three weeks. Inside that anaerobic period you may aspire to deliver some killer gym sessions as well as race-preparatory anaerobic endurance sessions like tempo sessions, intervals, and time trials. Recall that the Primal Blueprint recommends sprinting only once every seven to ten days, and only when feeling 100 percent rested and motivated. That means you are not going to be doing a whole ton of sprinting over the course of a year, which is fine. A little sprinting goes a very long way, while a little too much can be dangerous and destructive.

If you are like most endurance athletes and have paid little mind to sprinting to date, let’s start with a simple protocol to complete a safe, fun, and highly effective workout:

Pick the Right Day: Like the rocket or jet airplane analogy, make sure all systems are go before you even head out the door. First, this means high scores on the energy, motivation, and health tracker mentioned in Chapter 2. Second, this means you are respecting the periodization approach, have successfully built an aerobic base, and are in a brief high-intensity training period—a period characterized by significantly reduced training volume and with a focus on peak performance and extensive recovery.

Pick the Right Exercise: Running is the most beneficial type of sprinting because its weight-bearing nature enhances the cutting up effect and the bone density effect. If you have an insufficient general fitness base or significant injury concerns that preclude you from fast running, or have sport-specific competitive goals (e.g., cyclist, winter sport, or water sport athlete), you can certainly benefit from low- or no-impact sprinting. If you fall in the middle of the descriptions listed, you can choose uphill running sprints or sprinting in sand to lessen impact trauma but still develop your fast running abilities.

Here’s an important caveat to mention if your sport is indeed low or no impact: you can sprint much more frequently than mentioned previously throughout the book, as these comments and guidelines are framed from the perspective of sprint running, with the high-impact trauma and consequent extended recovery time. All competitive swimmers sprint at virtually every workout. Competitive cyclists—even lower-level amateurs—include sprinting in their workouts several days a week, and obviously can race day after day in the grand Tours. Whatever your sport, it’s critical to respect the periodization principles, but when you have an intensity period, you can proceed in accordance with the best practices in your sport.

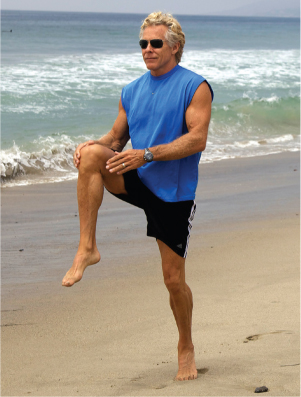

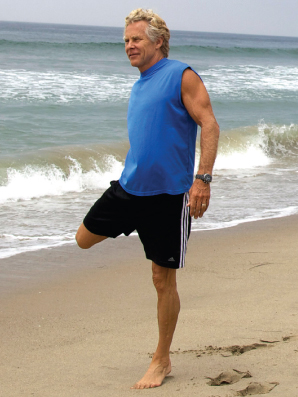

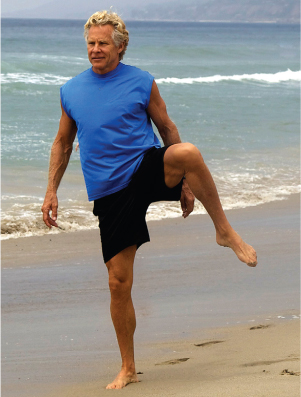

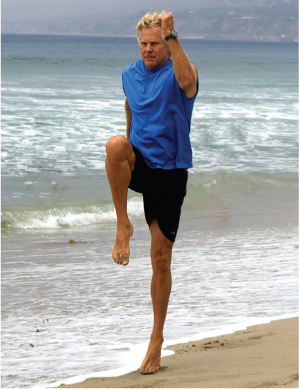

Warmup: As described previously, get your mind and body ready for the main event with a deliberate, focused warmup. For running, this includes an assortment of technique drills that help ingrain good form and further prepare your muscles, joints, and connective tissue for the forthcoming maximum efforts. Following are some images of good dynamic stretch warmup drills for sprinting.

Knee-to-chest: Gently pull knees up to chest and release.

Pull quads: Grab foot and pull gently to butt, release with forward step.

Open hips: Face forward, rotate knee up and along body line. Great for hip flexors.

Mini-lunge: Take exaggerated-length steps, front thigh nearing parallel. Don’t overdo this one; it’s just a warmup!

Hopping drill: Get the heart going now! Drive knee to chest while jumping up and forward, arms pumping. Land on same foot, repeat hop with other knee.

High knees: Toughest one last, almost ready to open the throttle and sprint! Exaggerate knee lift by slapping hands. Preserve tall, straight body, drive knees high, quick stride turnover. Remember these identical tips for actual sprinting!

Choose Appropriate Work Efforts: Sprints can last anywhere from ten to thirty seconds. This is little rationale for endurance athletes to attack sprints of less than ten seconds. Metabolically, these efforts burn pure ATP and are more applicable to athletes training for explosive sports like football, or the jumps, weight throws, and sprints in track and field. Max efforts from around eight seconds up to thirty seconds burn lactate for fuel, while going over thirty seconds kicks you into glucose burning. As stated previously, “sprinting” for over thirty seconds is not really sprinting; workouts with longer work efforts are categorized as intervals, tempo runs, time trials, or whatever. Here, we’re gonna go max or go home. Consequently, try starting with efforts lasting around fifteen seconds. Perhaps this equates with a fixed distance, like a half, two-thirds, or full length of a football field. Having a finish line to reach every time will help with your efforts to deliver consistent quality sprints—same duration, same distance covered, same effort scale.

Choose Appropriate Rest Intervals: With the aforementioned goal of delivering a consistent quality of sprint efforts, the main variable for your rest intervals is to ensure you are sufficiently refreshed and energized to deliver a consistent quality effort with each successive sprint. Your rest period should be sufficient enough for respiration to return to near normal, and for you to feel mentally refreshed enough to tackle another effort. Forget about stimulating any training effect from shortening your rest period and jumping into another sprint—save this type of training stimulus for interval workouts.

Mark likes to perform a novel session on the packed sand as follows: 10 strides cruising, 10 strides fast, 10 strides all out. Each sequence takes around 30 seconds—repeated six times. If you are concerned about impact, hard or soft sand is a great option!

Besides getting your respiration under control and muscles refreshed, you should also be vigilant about recovering from mental fatigue during your rest periods. Sprinting places an incredible demand on the central nervous system; you might benefit from just walking around and staring off into space before even thinking about your next sprint.

If you have difficulty focusing, concentrating, or even keeping your balance during a walk recovery interval, this is an indication that the nervous system is fried and that further sprint efforts are not necessary. All told, you will likely find yourself resting between thirty seconds to one minute between sprints fifteen seconds long.

Choose Appropriate Number of Reps: How many sprints to do? How about starting with five and seeing what happens? If you can only deliver a consistent quality effort for three, then that’s where you are right now. You can deliver a couple or a few quality sprint sessions and add additional reps over time. No matter who you are, all you ever need to do is six sprints of fifteen seconds, or perhaps four sprints of twenty seconds, or some similar combination of the two different sprinting times. The rest of your workout progression and application of increased fitness will be directed at going faster, not doing more, and not resting less.

Conduct Appropriate Cooldown: Pretty simple instructions here. You simply want to gradually transition from an active, pumped up, highly stimulated state to a resting, calm, relaxed state. Abrupt transitions in either direction—jumping right into a tough workout or jumping right into your car after a tough workout—overstress the delicate fight-or-flight response. Make the workout easier on your body and speed recovery by winding things down gradually.

When you complete your final sprint, keep moving slowly for at least five minutes, jogging if you were running or otherwise doing the same activity—easy pedaling, stroking, or swimming. When you feel your body temperature and your sweat rate start to regulate a bit, you can stop moving. Of course, your heart rate and other metabolic markers are not going to regulate for many hours (and that’s a good thing, as discussed with sprinting’s impact on fat metabolism), but you want to pull back from pedal to the metal at least to the 55 mph highway speed limit.

Recover Completely: The Primal Blueprint recommends sprinting only once every seven to ten days, and only when your mind and body are fully rested and energized for peak performance. A good sprint workout takes at least forty-eight hours to recover from, so structure your strength workouts accordingly so that you can have a couple of easy aerobic recovery days after your sprint sessions. Again, these time-frames relate to running sprints. If you do low- or no-impact sprinting, you can recover much faster—probably in a single day—and perform more sprints during your high-intensity training periods.