9

The Last Men on the Moon

This is what all astronaut-explorers are trained to do: journey to perilous places on dangerous missions—sometimes meeting the unexpected—and return, alive, with new truths, new knowledge, and new postflight wisdom on how to make future flights safer and better.

—Francis French and Colin Burgess, Into That Silent Sea

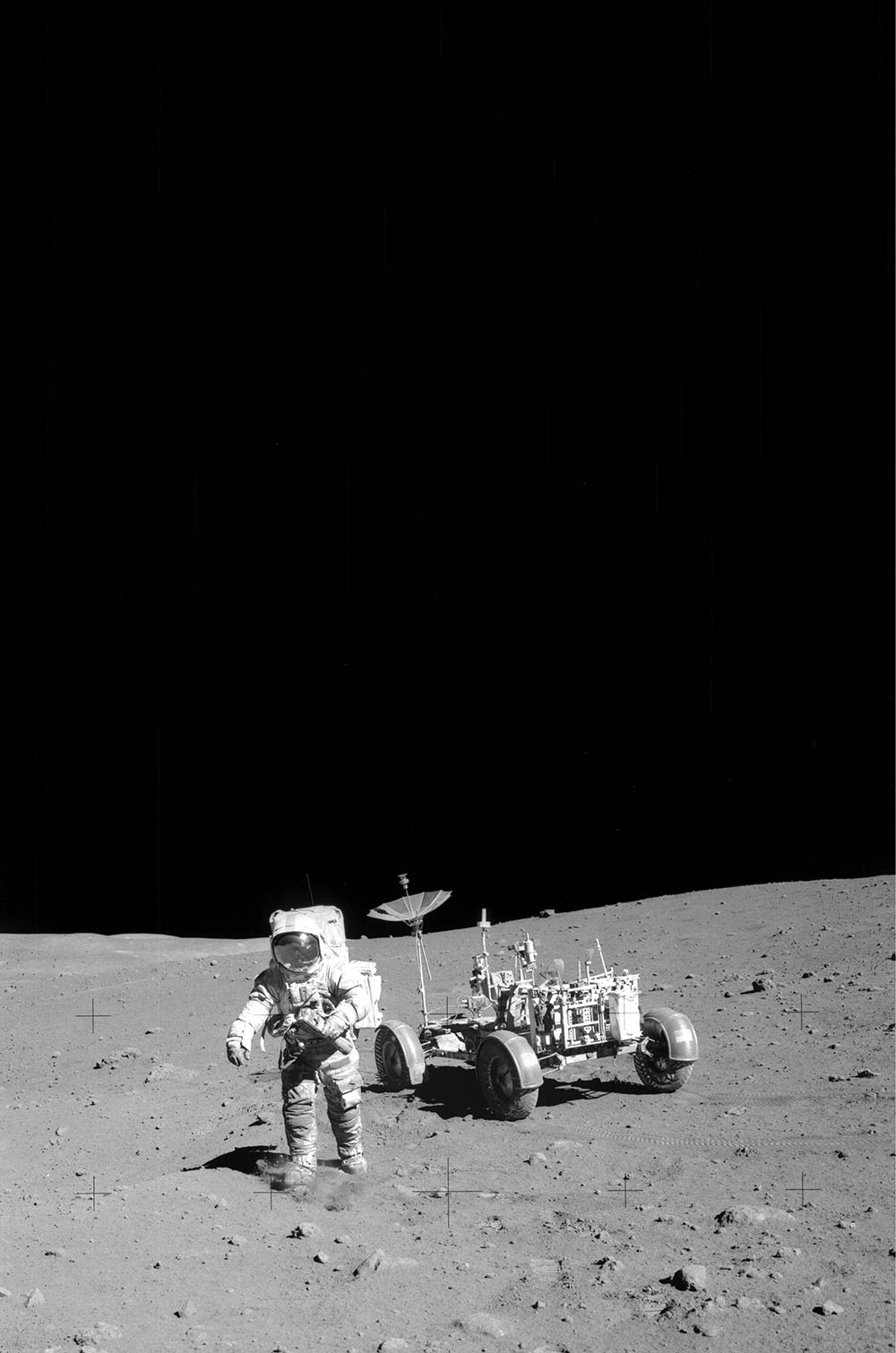

Astronaut Dave Scott on the rim of Hadley Rille with the lunar rover.

Each of the final three Apollo missions sent astronauts to a different area of the moon. NASA worked with geologists to pick landing sites that offered diverse landscapes with interesting features. They set up increasingly complex experiments so the trips would provide insights into how the moon was formed. The astronauts for these missions spent months ahead of time studying geology. They worked with experts and took field trips to the Rio Grande Gorge in New Mexico and the mountains of California. They learned to identify and describe various types of geologic structures.

Lunar exploration missions needed more geology equipment than early Apollo missions. NASA upgraded the lunar module to carry the extra weight. Engineers added powerful batteries so the spacecraft could stay on the moon longer. Early lunar landings included two moonwalks of about four hours each. Lunar exploration missions included three long excursions of about seven hours each. Engineers extended the astronauts’ exploration time by increasing life-support systems in the backpacks the men wore outside the spacecraft.

Apollo 15—Hadley Rille

Apollo 15 launched on July 26, 1971. It was the first mission designed to investigate the moon from orbit as well as from the lunar surface. Alfred Worden, the command module pilot, operated a scientific observation platform while he orbited the moon. He conducted experiments and photographed never-before-seen images of the moon’s surface. Scientists chose a mountainous region called Hadley Rille for Apollo 15’s landing site. A deep channel that looked like an empty riverbed wove across the area. The mountainous terrain made the approach tricky, but David Scott and James Irwin executed the landing perfectly.

Scott and Irwin stayed on the moon for three days. On the first day, Scott hopped down the ladder from the lunar module. He looked around at the stark landscape. “As I stand out here in the wonders of the unknown at Hadley, I sort of realize there’s a fundamental truth to our nature,” he said. “Man must explore. And this is exploration at its greatest.”

The astronauts loaded the rover, a battery-powered car with wire mesh wheels. Filled with geology equipment, cameras, and gear, the rover allowed the astronauts to roam miles from their landing site. The rover had a television camera mounted to the front. The camera allowed mission control and the world to watch the astronaut-explorers as they gathered clues to unlock the moon’s mysteries.

Apollo 15 astronaut David Scott waits in the lunar roving vehicle for astronaut James Irwin for the return trip to the lunar module, Falcon, with rocks and soil collected near Hadley Rille. Powered by battery, the lightweight electric car greatly increased the astronauts’ mobility and productivity on the lunar surface. It could carry two suited astronauts, their gear and cameras, and several hundred pounds of bagged samples.

Scott enjoyed driving his new car around the moon like a dune buggy on a lonely desert. “This is a super way to travel,” he said as he zipped across the lunar dust. “This is great.” The astronauts dodged craters and bounced past towering mountains. They chipped off samples of rocks, scooped dirt from various locations, and stored them in bags. They photographed all kinds of geological formations. They also set up scientific experiments on the lunar surface.

After nearly seven hours of exploring, Scott and Irwin returned to Hadley Base where the lunar module sat waiting for their return. They climbed up the ladder and took off their space suits. They ate and slept. The next morning, they prepared for their longest day of exploration.

Genesis and Galileo

Scott and Irwin drove to Mount Hadley Delta. They trekked across the side of the mountain, took samples, and described the terrain for the team of geologists watching in mission control. Then they headed to Spur crater. The astronauts noticed a small white rock. It stood out against the gray dust of the moon and caught their attention. Scott lifted the rock, about the size of his fist, and examined it. Large, white crystals sparkled in the sun. Both men marveled at their find. Laboratory tests would later reveal that the stone was a piece of the moon’s original crust. Scientists estimated it to be four billion years old. A reporter covering the Apollo 15 mission called it the Genesis Rock, a reference to the biblical creation story.

On their final day of lunar exploration, the astronauts drilled 10 feet (3 m) into the lunar surface and pulled out core samples. They set up equipment that would send data about the moon to Earth long after they were gone. Then Scott stood in front of the rover’s television camera and performed one last experiment. He explained that he was going to test Galileo’s theory that gravity acts equally on objects regardless of their mass. Because there is no air resistance on the moon, it was the perfect place to demonstrate the theory. “In my left hand, I have a feather; in my right hand, a hammer,” said Scott. “I’ll drop the two of them here and, hopefully, they’ll hit the ground at the same time.” Scott held out his arms and dropped the feather and the hammer. They hit the ground at the same time. “How about that!” Scott said. “Nothing like a little science on the Moon.”

Scott and Irwin packed their samples, closed the lunar module hatch, and blasted off from the moon. They joined Worden in the command module and headed back to Earth. As Apollo 15 came through the fluffy clouds drifting over the Pacific Ocean, one of the three orange-and-white parachutes holding the command module only partially inflated. The cone plunged into the ocean with a mighty splash. But the astronauts weren’t hurt. They emerged smiling and happy.

Apollo 16—Ken Mattingly’s Turn

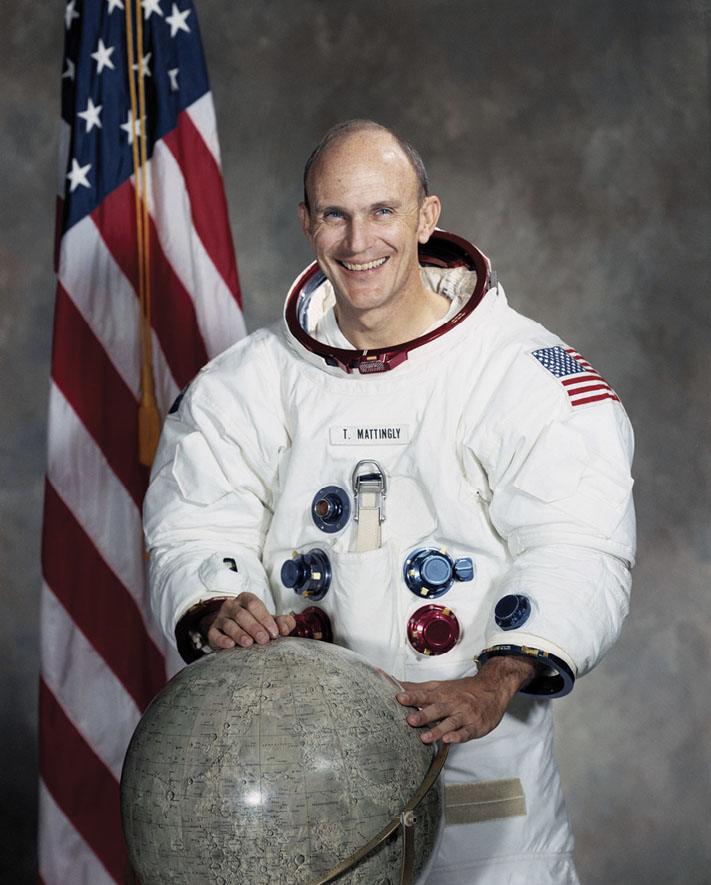

Ken Mattingly, bumped from the Apollo 13 mission because of his exposure to measles, was given another chance to go to space. On April 16, 1972, he flew as the command module pilot on Apollo 16. John Young was the mission commander, and Charlie Duke was the lunar module pilot. Apollo 16’s landing site was the Descartes Highlands. Scientists hoped the astronauts would find evidence of recent volcanic activity in the hilly area.

Astronaut Ken Mattingly

The flight went smoothly until the astronauts reached the moon and prepared to land. The command module and the lunar module undocked and separated. As the spacecraft orbited the moon, the command module started to shake. Mattingly changed some settings, but the spacecraft still shook. Mission control delayed the landing. If the steering system on the command module failed, the spacecraft could start tumbling. It would not be able to dock with the lunar module for the trip back to Earth, and all three astronauts would be lost.

While mission control investigated, the command module and the lunar module circled the moon in formation. For hours, the crew waited anxiously for a decision from Houston. After their sixteenth orbit, mission control told Mattingly that the engine might shake, but he would be able to control it. The crew could proceed with the landing. The command module continued to orbit, and the lunar module landed. They were six hours behind schedule, but Young and Duke were on the moon.

The next morning, Young and Duke put on their space suits and prepared for their first moonwalk. “Hot dog, is this great!” said Duke as he hopped down the lunar module ladder. “That first foot on the lunar surface is super.” The astronauts set up experiments, drove the rover to various craters, and took samples. They brought back more than 200 pounds (91 kg) of samples but did not find any recent volcanic rock. Instead, their mission provided evidence that the moon was shaped by eons of meteorite bombardment. When the astronauts were ready to head back to Earth, Young drove the rover away from the lunar module and pointed its television camera toward the spacecraft. Then he walked back to the spacecraft and prepared to take off. Flight controllers at mission control captured the liftoff from the moon on live TV.

From lunar orbit, the astronauts launched a subsatellite. The small satellite circled the moon for thirty-four days and sent information about its mass, gravity field, and magnetic field back to Earth. On the coast back to Earth, Mattingly took an eighty-four-minute space walk. He floated to the service module and retrieved film cassettes from the Scientific Instrument Module. Equipment in this module had recorded all kinds of data about the lunar environment as Mattingly circled the moon. Scientists studied the information brought back from Apollo 16 for years.

Apollo 17: The Last Lunar Landing

Apollo 17 launched on December 7, 1972. Gene Cernan, the flight commander, had flown on Gemini 9 and Apollo 10. It was the first spaceflight for Ron Evans, the command module pilot, and Harrison “Jack” Schmitt, the lunar module pilot. Rather than a degree in engineering and a military background (the typical astronaut background), Schmitt earned a PhD in geology from Harvard University. He completed a year of flight training and became a jet pilot before he was considered for spaceflight. Then he trained as an astronaut. Schmitt was the first scientist-astronaut to explore the moon.

The Apollo 17 landing site was a mountainous area, Taurus-Littrow. The area was thick with craters and rich in geological wonders. Boulders that had been flung out of the craters were strewn around the area. Scientists believed the highlands contained rocks both older and younger than those found on other missions, and so they hoped Apollo 17 would answer questions about how and when the moon had formed.

Cernan and Schmitt explored the lunar surface. Evans conducted experiments from lunar orbit. On the first day, Cernan’s hammer snagged the right rear fender of the rover and tore off the thin material. When the men drove to their geology sites, clouds of moondust rained down on them. The dust threatened to clog the rover’s gears and damage scientific instruments. It also put the astronauts in danger. As moondust turned their white space suits black, the dark color absorbed the sun’s intense heat. The men had to brush off the abrasive grit, which had worked its way into every nook and cranny, before they entered the lunar module for the night.

Scientist and astronaut Jack Schmitt, lunar module pilot, retrieves samples from the lunar surface for study.

In Houston, while the men on the moon slept, NASA engineers worked out a fix for the rover’s fender—a replacement fender. The next morning, astronaut John Young explained to the crew how to fashion the fender from four laminated lunar surface maps, duct tape, and lamp clamps. Cernan and Schmitt mounted the fender on the rover and attached it with the clamps. It worked, and the second day of lunar exploration began.

When the mission was finished, Cernan pulled the makeshift fender off the rover and brought it back to Earth. It was displayed at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum in Washington, DC. Cernan and Schmitt drove in the lunar rover for more than an hour to South Massif. As Cernan darted past craters and swerved around boulders, Schmitt described the landscape to the scientists in Houston. The explorers took many bags of samples and then cruised to the next crater on their list and the next. At Shorty, a deep crater littered with rocks, Schmitt found streaks of orange moondust. Everything else they had found was light gray, dark gray, or tan. This was bright orange.

The astronauts hoped the orange soil would be proof of recent volcanic activity on the moon. The men carefully bagged samples of the orange dust. Scientists later confirmed that an explosive volcanic eruption created the soil, but tests showed it occurred about 3.7 billion years ago.

The final day of lunar exploration lasted more than seven hours. Cernan and Schmitt drove to the opposite end of the Taurus-Littrow Valley, the North Massif. They took samples from a huge boulder that had rolled down the mountain and split into five pieces. They trudged up steep slopes and hammered out chunks of rocks until their arms and hands ached.

Pictured is the Apollo 17 landing site at Taurus-Littrow.

After they loaded the lunar module for the last time, the astronauts recorded a message for a group of young people in Houston. NASA had invited students from seventy countries to watch Apollo 17’s final moonwalk. “One of the most significant things we can think about when we think about Apollo is that it has opened for us, ‘for us,’ being the world, a challenge of the future,” said Cernan. “The door is now cracked, but the promise of the future lies in the young people, not just in America, but the young people all over the world learning to live and learning to work together.”

Schmitt handed Cernan a moon rock. “It’s a rock composed of many fragments, of many sizes, and many shapes . . . that have grown together to become a cohesive rock, outlasting the nature of space, sort of living together in a very coherent, very peaceful manner. . . . We hope that this will be a symbol of what our feelings are, what the feelings of the Apollo Program are, and a symbol of mankind: that we can live in peace and harmony in the future.”

Cernan uncovered a plaque attached to the portion of the lunar module that stayed on the moon. Two maps represented the world, the western half and the eastern half. Between the maps of Earth sat a small diagram of the moon with the landing sites of each Apollo mission shown. Cernan read the inscription on the plaque. “Here man completed his first exploration of the Moon, December 1972 A.D. May the spirit of peace in which we came be reflected in the lives of all mankind.” Each of the Apollo 17 astronauts and Nixon had signed the plaque.

The final Apollo mission broke every record of the lunar landing program. Its astronauts stayed on the moon longer, drove farther, collected more samples, set up more experiments, and took more photographs than any Apollo mission had. Their mission was also the smoothest and most trouble-free.

Apollo 17 marked the end of an era. No one has stepped on the moon since 1972. For some, the end brought relief. They hoped, instead, to spend space exploration dollars to wipe out poverty, social unrest, and many other problems in the United States and around the world. For others, the end of Apollo brought sadness and a time of reflection. “Of all humankind’s achievements in the twentieth century . . . the one event that will dominate the history books a half a millennium from now will be our escape from our earthly environment and landing on the moon,” said broadcast journalist Walter Cronkite.

After the Apollo program ended, NASA lacked a clearly defined goal for space exploration. Some people at the agency and in Congress wanted to focus on finding a way to reach and explore Mars. Others thought resources should be spent building reusable space shuttles. And still others thought building a space station was the top priority. Nixon cut NASA’s budget. Unlike Kennedy, he did not lay out a clear-cut goal for space exploration that NASA could embrace.

If space exploration was going to continue, NASA needed a new vision.