2

The Race for Space

The exploration of space will go ahead, whether we join in it or not, and it is one of the great adventures of all time, and no nation which expects to be the leader of other nations can expect to stay behind in this race for space.

—President John F. Kennedy

On June 3, 1965, astronaut Ed White became the first American to walk in space.

Apollo 13 was the third NASA mission to send astronauts to land on the moon. Thousands of scientists, engineers, and mathematicians worked for more than a decade to accomplish this extraordinary feat.

And it started with a race.

The Cold War

After World War II (1939–1945), the United States and the Soviet Union (a former nation of republics that included Russia) saw each other as a threat. Both nations had nuclear weapons and feared an attack by the other. This period of suspicion between the United States and the Soviet Union was the Cold War (1945–1991).

The United States practiced a democratic form of government. Its economy was based on capitalism, a system where individuals and companies own goods. The Soviet Union practiced a Communist form of government. The Communist government controlled the economy. Both countries wanted to prove to the world that their form of government and economic system were the best. Landing a person on the moon was a dramatic way to accomplish that and to avoid an all-out war.

On October 4, 1957, the Soviet Union launched Sputnik I, the first satellite, into space. The achievement shocked the United States. It proved the Soviet Union had surpassed the US in technological skills. The US felt its national security was under threat. If the Soviets could launch a satellite into space, they could just as easily lob a nuclear bomb at the United States. The reputation of the country was in jeopardy. America had to catch up quickly.

In response to Sputnik I, President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed the National Aeronautics and Space Act. On October 1, 1958, NASA was formed as a civilian agency within the national government. NASA’s purpose was to explore space and obtain scientific knowledge. It would develop spacecraft and create programs to launch Americans into space.

Building a Space Agency

Space exploration is a complicated business, and NASA had much to learn. They had to figure out how to build a spacecraft that was safe for people to ride in, how to attach it to a rocket and blast it into space, how to keep it moving in the right direction, and how to bring it safely back to Earth. The people working at the agency were modern pioneers in the frontier of space.

German scientist Wernher von Braun and a team of rocket scientists developed rockets powerful enough to break through Earth’s gravity. Rival companies in the United States competed against one another to build spacecraft that would protect astronauts from the harsh environment of space. NASA set up the Mission Control Center in Houston, and flight controllers developed procedures to make sure each phase of each mission was a success. Engineers developed computing, communications, and guidance systems to enable mission control to communicate with and assist astronauts in flight. NASA also set up tracking stations around the world. These stations would enable them to monitor the location of spacecraft from various points around the globe. These innovations were designed with computers less powerful than a Wi-Fi router.

Besides building hardware, NASA set the requirements for astronaut candidates. They began with military test pilots, which meant that all the candidates were men because women couldn’t serve in the military as pilots in 1959. From that initial group, NASA outlined requirements for age, height, education, intelligence, temperament, and physical ability. The men had to be less than forty years old and less than 5 feet 11 inches (1.8 m). They had to have a bachelor’s degree in engineering, science, or math. They had to be qualified jet pilots with a minimum of fifteen hundred hours flying time. And they had to be in excellent physical and mental condition.

Candidates went through rigorous physical and psychological testing. NASA eliminated the majority for one reason or another. From a field of five hundred candidates, NASA selected only seven men to be astronauts: Gordon Cooper, Scott Carpenter, John Glenn, Deke Slayton, Wally Schirra, Gus Grissom, and Alan Shepard. According to Dee O’Hara, the medical nurse for the astronauts, “They were the best America had to offer. . . . They put their backsides on the line because it was such a new program—new everything—and they stepped up to the plate and did it.”

Project Mercury

Project Mercury, America’s first human spaceflight program, began in 1958. Its purpose was to send astronauts into space and test the effects of space travel on people. A series of six missions from 1961 to 1963 worked toward the goal of sending a manned spacecraft into orbit around Earth.

Before NASA launched the first human into space, it had to test the spacecraft thoroughly. Many early mishaps occurred while developing rockets and training astronauts. Many rockets blew up on the launchpad or exploded a few feet in the air. According to Guenter Wendt, a mechanical engineer for McDonnell Aircraft, the company that built the Mercury spacecraft, “We launched between fifteen and twenty rockets a week, but three out of five would blow up.”

With each attempt, engineers gained valuable knowledge and moved closer to their goal. By January 1961, NASA felt confident enough to launch a chimpanzee named Ham into space. After Ham returned safely to Earth, NASA went ahead with plans to send up the first human.

On January 31, 1961, a chimpanzee named Ham paved the way for the first American in space when he rode a Mercury-Redstone rocket on a suborbital flight and returned safely to Earth.

In spite of the risks, all seven astronauts wanted to be first to fly into space. For long hours, they trained intensely for a job no one had ever done. Shepard told a reporter, “Of course, I want to be first. The challenge is there, and I’ve accepted it.”

Glenn agreed. “I think that anyone who doesn’t want to be first doesn’t belong in this program.”

But the Soviet Union beat the US. On April 12, 1961, Russian cosmonaut, or astronaut, Yuri Gagarin piloted a Vostok spacecraft into Earth orbit. The US space program reeled with disappointment. The Soviet Union was ahead in the space race.

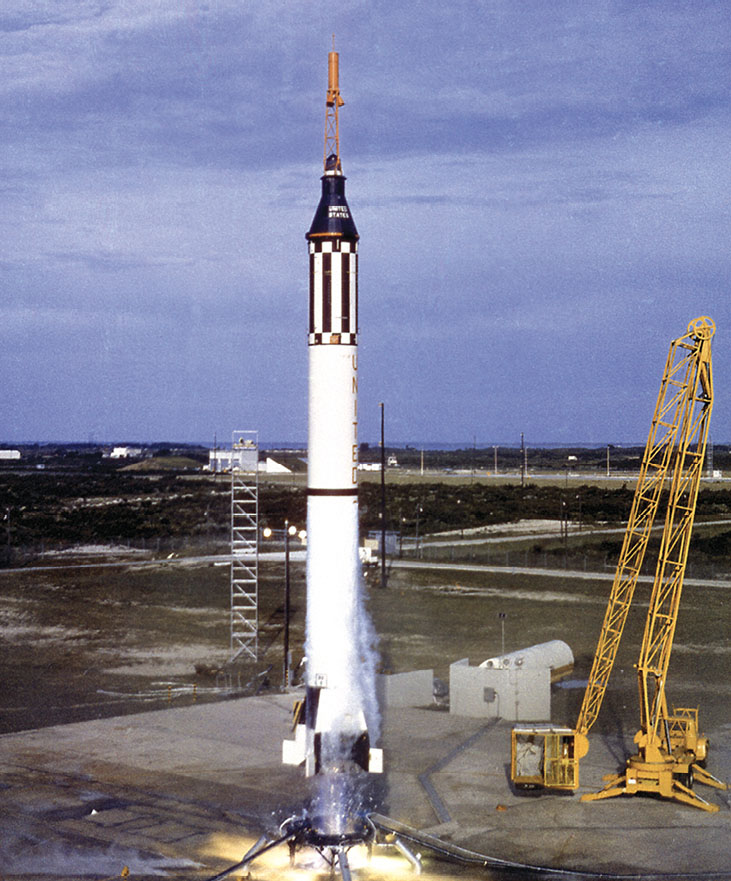

On May 5, 1961, the first American blasted into space. Shepard lifted off on Freedom 7, named in honor of the seven original astronauts. He flew 116 miles (187 km) high and then returned to Earth. The flawless fifteen-minute flight was broadcast around the world. When Shepard’s capsule splashed down in the Atlantic Ocean, church bells rang, sirens wailed, and cheering crowds streamed into the streets in his hometown of Derry, New Hampshire. The astronaut became an instant celebrity.

Three weeks after Shepard’s historic flight, Kennedy stood in front of a joint session of Congress and ignited the fire of America’s space race. “I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the Earth. No single space project in this period will be more impressive to mankind, or more important for the long-range exploration of space; and none will be so difficult or expensive to accomplish.”

With Shepard’s success and the president’s challenge, the US space program took off. On July 21, 1961, Grissom piloted Liberty Bell 7. The fifteen-minute flight went smoothly—until the recovery phase. The spacecraft splashed down in the Atlantic Ocean, and Grissom waited for a helicopter to pluck him out of the water. All of a sudden, the hatch blew off and water poured into the capsule. Grissom pulled off his helmet and hurled himself into the rough sea. He swam away from the spacecraft and watched in horror as it slowly filled with water and sank. Water seeped into Grissom’s space suit, making him heavier and heavier. “At this point the waves were leaping over my head, and I noticed for the first time that I was floating lower and lower in the water. I had to swim hard just to keep my head up.”

Rescue helicopter pilots lowered a sling and hoisted the astronaut out of the sea. They flew Grissom to the USS Randolph, an aircraft carrier waiting nearby. As Grissom mourned the loss of his spacecraft, a ship’s officer handed him his space helmet. One of the rescue pilots had snatched it out of the water near a circling 10-foot (3 m) shark.

On July 21, 1961, Mercury-Redstone 4 (MR-4) launched. Astronaut Gus Grissom piloted Liberty Bell 7 on a fifteen-minute suborbital flight.

Orbiting Earth

As NASA worked on plans for a US spaceflight to orbit Earth, twenty-five-year-old Russian cosmonaut Gherman Titov spent a full day in space aboard Vostok 2. He orbited Earth seventeen times, and he was the first person to eat and sleep in space.

Discouraged but not defeated, the US space program plunged ahead. NASA selected Glenn as the first American to orbit Earth. Bad weather delayed the launch for nearly two months. On February 20, 1962, Glenn orbited Earth three times on Friendship 7. The flight went smoothly until a warning light flashed in mission control. The light indicated that the heat shield on Friendship 7 had come loose. The heat shield protected the spacecraft from the intense heat of reentering Earth’s atmosphere. Without it, Glenn would burn up in seconds.

On February 20, 1962, astronaut John Glenn entered the capsule, Friendship 7. He blasted into space on a Mercury-Atlas 6 rocket and became the first American to orbit Earth.

Mission control considered its options. Possibly, a faulty instrument was giving the reading and the heat shield was fine. NASA had never encountered a similar problem in training exercises or previous spaceflights. An accurate warning signal could mean heat shield failure, a horrible death for Glenn, and an unrecoverable blow to the US space program. Some mission control staff felt it was an instrument error, and they should do nothing. Others thought they should try to hold the heat shield in place somehow.

Mission control decided to hold the heat shield in place by leaving the retropack (a group of rockets under the heat shield) attached to the spacecraft. Normally, the retropack was released after it fired. If mission control left the retropack attached, it might hold the heat shield in place. But the retropack could also damage the heat shield or change the trajectory, or path, of the spacecraft on reentry. The agonizing decision for mission control worked. The heat shield held, and Glenn returned safely to Earth, a new American hero. NASA later determined the heat shield was never loose. The problem was an instrument error.

Carpenter, Schirra, and Cooper also piloted Project Mercury missions. They orbited Earth and conducted scientific experiments. They performed maneuvers and tested various parts of the spacecraft. They ate and drank during spaceflights. When doctors examined each of the men upon their return, they confirmed that people could survive in weightlessness. NASA felt confident to move on to longer flights in its quest to reach the moon.

While NASA completed the Project Mercury missions, the Soviet Union launched Vostok 3 in August 1962. A day later, they launched a second manned spacecraft. The two spacecraft orbited Earth at the same time, and Vostok 3 stayed in space for ninety-four hours, longer than any previous flight. The Soviet government celebrated the achievement, boasting to the world’s press, “Communism is scoring one victory after another in its peaceful competition with capitalism.”

The US couldn’t seem to catch up in the space race. On June 16, 1963, Valentina Tereshkova, a Soviet, became the first woman in space. And in March 1965, Alexei Leonov became the first person to venture outside a spacecraft in a space suit.

Project Gemini

NASA learned a great deal about spaceflight from Project Mercury. But the agency still had much to accomplish before it would be able to send people to the moon and bring them back safely to Earth.

A mission to the moon and back would take nine to fourteen days. Cooper had stayed in space for thirty-four hours on the final Project Mercury flight. NASA needed to make sure the human body could withstand the stress of spaceflight for two weeks. NASA also had to develop safe space suits so that the astronauts could walk on the surface of the moon. Finally, NASA had to find a way for two spacecraft to rendezvous, or meet and fly together, in space. One spacecraft needed to take off from the lunar surface, rendezvous with another spacecraft orbiting the moon, and return to Earth. All these goals were part of NASA’s second human spaceflight program, Project Gemini, and all had to be met before NASA could attempt a lunar landing.

Valentina Tereshkova, the first woman in space, in front of the Vostok 6 in 1963. It would take the US until 1983 to send a woman to space.

The first two Gemini flights were unmanned and tested the new Titan II rocket. Two-man crews flew ten Gemini missions in 1965 and 1966. Gemini 3 astronauts Grissom and John Young orbited Earth three times. They tested the newly designed Gemini spacecraft, its onboard computer system, and its flight crew equipment.

The fourth Gemini flight, Gemini 4, reached the goal of a four-day flight. Gemini 4 also achieved another milestone. Astronaut Ed White ventured outside the spacecraft in a space suit. During his twenty-minute space walk, White was connected to the spacecraft with a cable. Pilot Jim McDivitt flew the spacecraft and took pictures of his fellow astronaut floating above the dazzling blue Earth. “This is the greatest experience,” White said. “It’s just tremendous.”

Project Gemini closed the gap in the space race. Gemini 5 stayed in space for eight days. In December 1965, Gemini 6 and Gemini 7 met in space and flew in formation. Gemini 7 stayed in space for two weeks. Gemini 8 successfully docked with, or connected to, another spacecraft. During Gemini 9, 10, 11, and 12, astronauts tested different ways of docking with other spacecraft. They also performed space walks of longer durations. The knowledge and technical expertise gained on Project Gemini made a lunar landing possible. NASA moved into its third phase of space exploration with a project to reach the moon. They called the project Apollo.

Apollo Tragedy

The Apollo program went live in 1967. Only three years remained to land human beings on the moon by the end of the decade. Design challenges slowed progress on the three-person Apollo spacecraft, which was far more complex than Mercury or Gemini spacecraft. The Apollo spacecraft had to sustain three men for two weeks or more in Earth orbit or lunar orbit. It had to hold enough fuel for the long trip to the moon and back. And it needed a more powerful rocket to blast it into space.

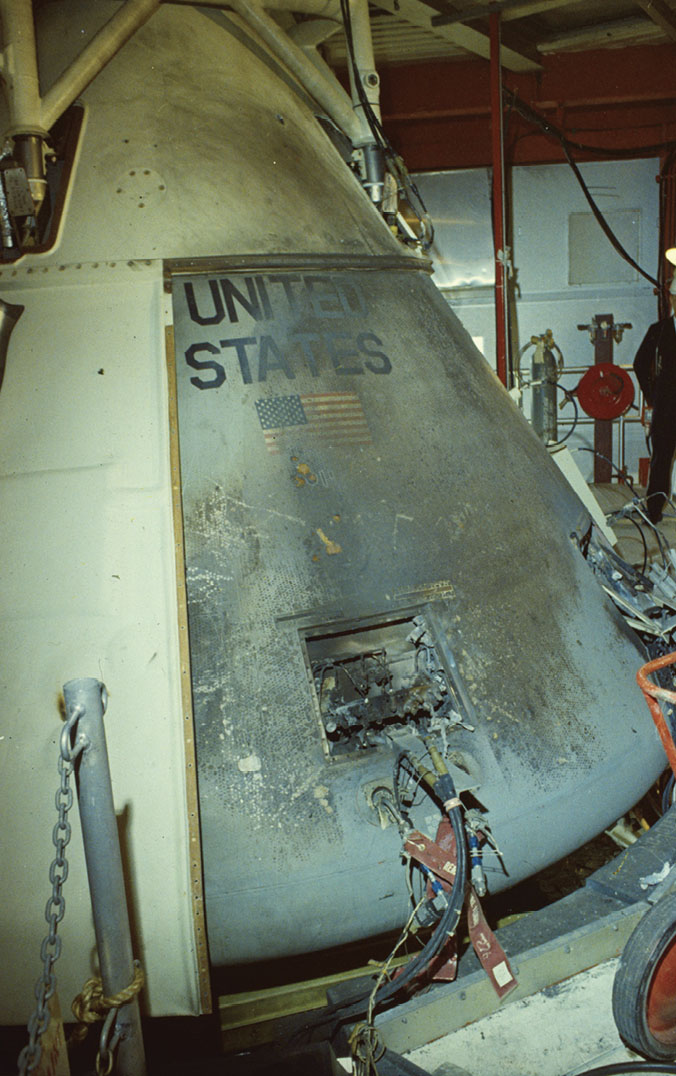

On January 27, 1967, Grissom, White, and Roger Chaffee tested the launch of the new Apollo spacecraft. For more than five hours, they sat strapped inside the capsule and went through a dress rehearsal for the first Apollo launch. They noted several problems with the communications system. Mission control struggled to hear them through crackling static. As the countdown wound down, a piece of exposed wiring produced a spark. The capsule, filled with pure oxygen, burst into flames.

The astronauts struggled to open the hatch, but it wouldn’t budge.

“We’ve got a bad fire,” Chaffee shouted. “We’re burning up here!”

Flight controllers nearby saw a flash of bright orange light. They grabbed fire extinguishers and ran toward the inferno. But flames, thick smoke, and poisonous fumes made reaching the trapped men impossible. It took five minutes to open the hatch, and by then it was too late. The capsule looked like the inside of a furnace. All three astronauts were dead.

The Apollo 1 disaster stunned the nation. The US Senate investigated, held hearings, and made recommendations. NASA went over every inch of the spacecraft and made massive design changes. The thousands of people who worked on Apollo pledged to reach Kennedy’s goal of landing on the moon. They recalled Grissom’s words from an interview one week before the tragedy. “If we die we want people to accept it. . . . We hope that if anything happens to us it will not delay the program. The conquest of space is worth the risk of life.”

Apollo 1 astronauts Gus Grissom, Ed White, and Roger Chaffee were killed when a fire swept through the oxygenated command module during a preflight test on January 27, 1967.

Apollo Triumph

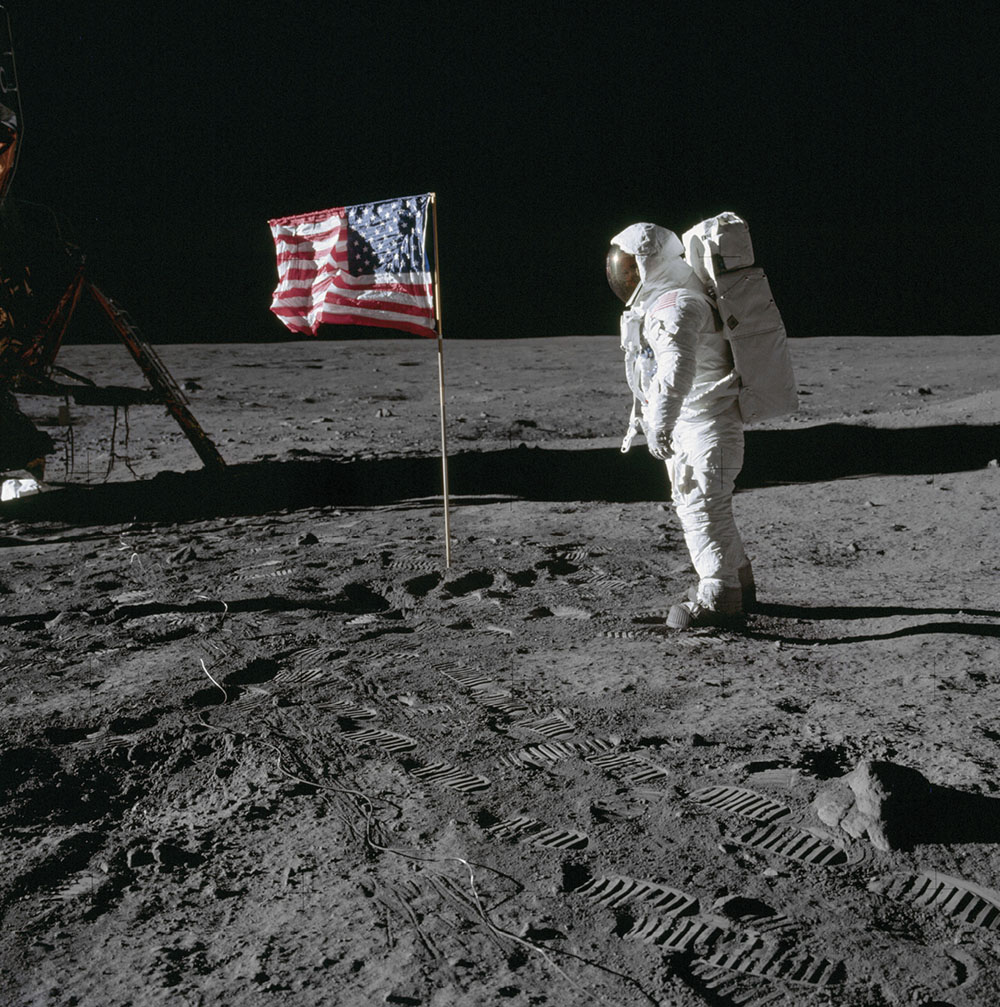

NASA forged ahead with a newly designed Apollo spacecraft. Engineers called it the safest spacecraft ever built. NASA carefully tested every aspect of the new design. They launched three unmanned test flights to make sure everything worked properly. Then they tested the spacecraft with astronauts orbiting Earth, and then orbiting the moon. Finally, on July 16, 1969, NASA launched Apollo 11. Astronauts Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Michael Collins flew the spacecraft Columbia into orbit around the moon. Then, on July 20, Armstrong and Aldrin detached the lunar landing module, Eagle, and touched down on an area of the moon called the Sea of Tranquility. “Houston, Tranquility Base here,” Armstrong said. “The Eagle has landed.” Armstrong lowered a small TV camera and then slowly backed down the spacecraft ladder. Six hundred million people around the world watched. When he stepped onto the moon’s pale gray, powdery surface, Armstrong said, “That’s one small step for man. One giant leap for mankind.”

Aldrin joined Armstrong a few minutes later. The astronauts planted an American flag on the moon. They conducted scientific experiments, collected rock samples, and took many photographs. They talked to President Richard Nixon at the White House. And they left behind a commemorative plaque:

Here Men From the Planet Earth

First Set Foot Upon The Moon

July 1969 A.D.

We Came In Peace For All Mankind

Collins circled the moon in Columbia. The lunar explorers completed their objectives, returned to the Eagle, and rested. Then they blasted off the lunar surface and rejoined Columbia for the trip back to Earth. Four days later, the trio splashed down in the Pacific Ocean. John F. Kennedy’s dream had become a reality.

Astronaut Buzz Aldrin, Apollo 11 Lunar Module pilot, poses for a photograph beside the US flag that he and Commander Neil Armstrong placed on the moon on July 20, 1969.

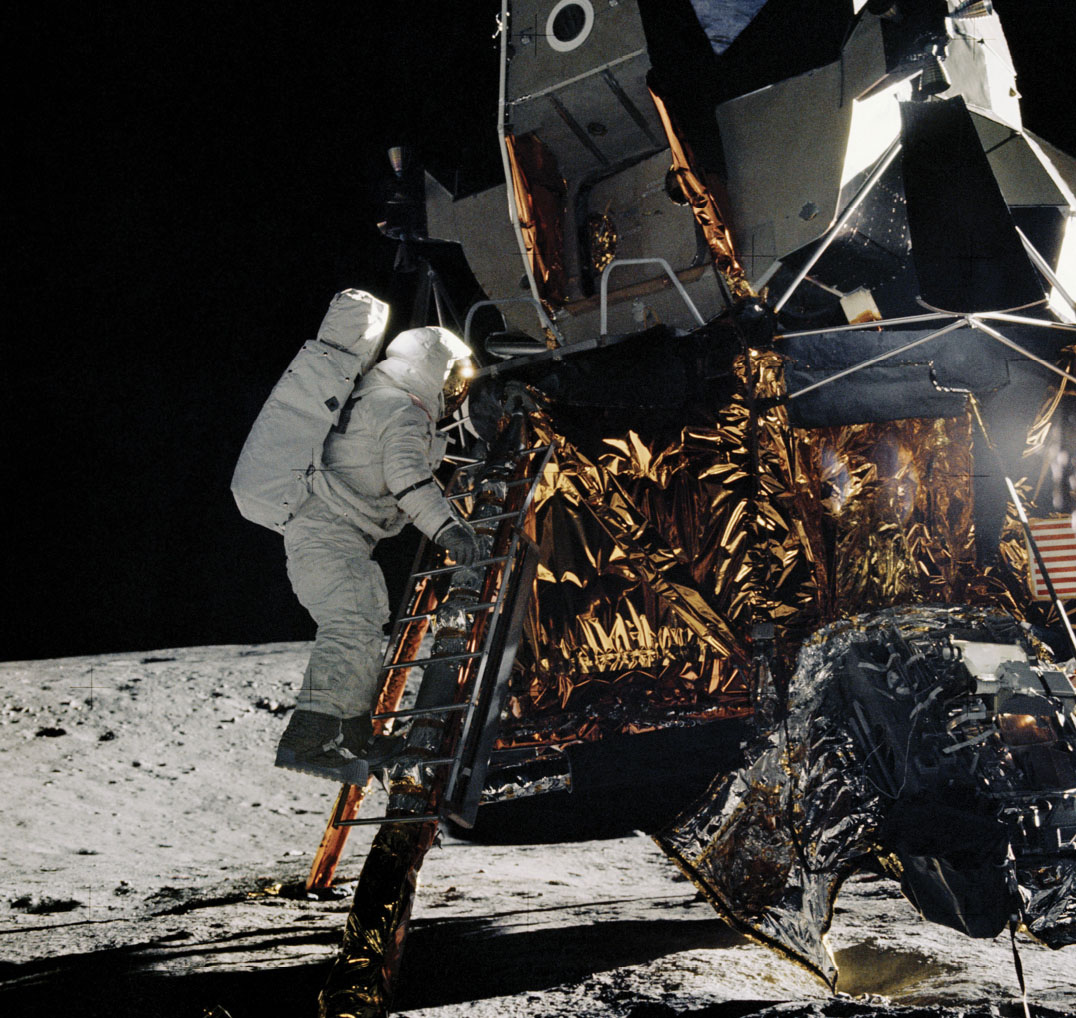

Apollo 12 also landed on the moon. Astronauts Charles “Pete” Conrad and Alan Bean touched down in the Ocean of Storms. The astronauts performed two moonwalks and stayed on the lunar surface for seven hours and forty-five minutes. They conducted experiments, brought back many rock and soil samples, and returned safely to Earth.

Astronaut Alan Bean, Apollo 12 Lunar Module pilot, prepares to step off the ladder of the lunar module and explore an area of the moon called the Ocean of Storms with the commander Charles Conrad.

Then came Apollo 13. Jim Lovell and Fred Haise planned to land in the Fra Mauro highlands. Theirs was a true scientific mission, with lots of experiments planned. After the explosion on board, the astronauts weren’t sure they would be able to land on the moon. They weren’t even sure they’d make it back to Earth.

It was the greatest challenge the US space program had ever faced.